Nicodemus Visiting Christ

| Nicodemus Before Christ | |

|---|---|

| Nicodemus Coming to Christ, Nicodemus | |

Nicodemus Visiting Jesus, by Henry Ossawa Tanner | |

| Artist | Henry Ossawa Tanner |

| Year | 1899 |

| Subject | Christ's discourse with Nicodemus |

| Dimensions | (33 11/16 in × 39 1/2 in) |

| Location | Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia |

| Accession | 1900.1 |

Nicodemus Visiting Christ is a painting by Henry Ossawa Tanner, made in Jerusalem in 1899 during the artist's second visit to what was then Palestine.[1] The painting is biblical, featuring Nicodemus talking privately to Christ in the evening, and is an example of Tanner's nocturnal light paintings, in which the world is shown in night light.[2]

It was Tanner's entry to the 1899 Paris Salon.[3] The painting was purchased by the Wilstadt Collection in Philadelphia and is now in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), Tanner's Alma Mater in the United States.[4][1][5] It won the Lippincott Prize for the best figurative work at PAFA's annual exhibition in 1899.[1]

Religious paintings

Nicodemus Visiting Jesus was inspired by the Gospel of John, 3:1-21.

There was a man of the Pharisees, named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews: The same came to Jesus by night, and said unto him, Rabbi, we know that thou art a teacher come from God: for no man can do these miracles that thou doest, except God be with him. Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God. Nicodemus saith unto him, How can a man be born when he is old? can he enter the second time into his mother's womb, and be born? Jesus answered, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again.[6]

Nicodemus became a convert after the evening's conversation.

The painting was among a lifetime of work illustrating biblical stories. The story was important to Tanner's father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, who considered it "biblical precedent for the worship habits of African-American slaves" in their practice of worshiping at night.[7]

Tanner's father, an African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop, had wanted Tanner to follow him into the ministry.[8] In becoming an artist, Tanner disappointed his father's dream; however his brush created paintings of which his father could approve.[8]

By 1908, when Tanner held his "first major solo exhibition" in the United States (the first after having become famous), he was known for his religious artwork.[9][10] The exhibition featured a long list of religious subjects, 33 paintings including:[11][10] Abraham’s Oak, Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh, Christ and Nicodemus, Christ at the Home of Mary and Martha, Christ on the Road to Bethany, Christ Washing the Disciples’ Feet, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, Death of Judas, The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water, Escape of Paul, Flight into Egypt, The Good Shepherd, He Vanished Out of Their Sight, Head of Old Jew, Hebron, The Hiding of Moses, Hills near Jerusalem, Jerusalem Types (4 under this name), Judas Covenanting with the High Priests, Mary, Mary Pondered All These Things in Her Heart, Moonlight—Hebron, Moses and the Burning Bush, Nicodemus, Night (After the Denial by Peter), Night of the Nativity, On the Road to Emmaus, Return of the Holy Women, Two Disciples at the Tomb, The Wise Men.

Missing from the exhibition were famous works whose museums would not release them: The Annunciation, The Resurrection of Lazarus and The Pilgrims of Emmaus.[12]

- Image from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

- Another digital copy, lightened for cell phone screens.

Evening light

A newspaper commented in 1909 that Tanner found the daylight in the Middle East harsh and chose to paint at night.[2] Helen Cole, writing for Brush and Pencil commented on the choice of lighting at night, calling it a "moonlight scene, only the two figures, enveloped in a cold blue light...the effect of night and remoteness and loneliness was exceedingly well rendered."[14]

Tanner lit the Nicodemus Visiting Christ with multiple sources of light.[15] The sky is lit with twilight (in which the Sun's rays come from below the horizon and are filtered through the atmosphere, casting blueish light). Moonlight is present, casting distinct shadows and warmer green-yellow light on the rooftop, distant buildings and trees.[15] Orange light as from a candle or fire is reflected on the stairs from below, lighting the face of Christ.[15][16]

Tanner used light to indicate holiness. In paintings such as the Holy Family, Tanner used light from elsewhere to illuminate the veil of Mary, making it glow in darkness, the baby Jesus also in light. In Invitation to Christ to Enter by his Disciples at Emmaus, the light centers on Christ as if emitting from him.

In this Nicodemus Visiting Jesus, light also indicates holiness.[13] The study painting for this showed Christ silhouetted by the Moon, creating a halo.[13] In the final painting, the effect was more subtle, the moonlight reflecting on the cloth over Christ's head and glowing on his chest, the firelight lighting his face.[13][15] And Tanner shows Nicodemus having approached Jesus, who is lit with ambient light to imply holiness.[13][15]

And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil. For every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved. But he that doeth truth cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest, that they are wrought in God.[17]

Multiculturalism

European and American artwork in the 19th and 20th centuries tended to show Jesus as a white man, often glowing white, and Jewish people as having European features.[18][19][20][21] Similarly, there was and is a movement promoting a colored or non-white Jesus.[22]

Rather than focus on race when painting Jesus, Tanner created a "comopolitan" Christ, a "universal" figure meant to be viewed religiously rather than in a racial sense.[23][24] Further, Tanner wanted his paintings to be viewed without consideration of the artist's race.[25] Tanner chose to portray experiences common to everyone, a quiet evening conversation and a teaching moment, a common focus to bring people together with "religious language" that they had in common.[26] He chose to paint ordinary human experiences, places, and relationships to "connect rather than to divide viewers."[26] He found that in France this was possible, while in America, newspaper reviewers tended to focus on his race instead of on his art.[25][27]

The tendency to consider Tanner's artwork in terms of race hasn't ended; race is one of the elements looked at in the United States when considering artwork. Who made the painting, and did they have a message (even unintentionally) about race? Because of this history, those studying his Tanner's art in the United States have commented on Tanner's depiction of race in the image and how the shadows and "conflicting light sources" in the image "look deliberately calculated by the artist to obfuscate the figure's (Christ's) appearance."[28] Similarly it has been noticed that in Flight into Egypt (1899), Tanner painted people who were rendered indistinctly in twilight, so that it was difficult to pin them down as being from a particular race or ethnic group; people could imagine their own in the painting.[29]

Tanner had an eye for details of race and ethnicity which he applied to observing people in the Middle East.[26] Tanner (like other Orientalists) catalogued the way people in the Middle East looked, the varieties of racial and ethnicities and painted with these.[30] The painting Nicodemus Before Christ shows results of observations. He made study paintings throughout his trips, including one used for this artwork; the Nicodemus in this painting is thought to be based on Head of a Jew in Palestine, a study painting which Tanner would keep and rework throughout his lifetime.[31] Tanner depicted Jesus more ambiguously than was standard for an American; even though symbolically lit to show holiness, Tanner's Jesus could be seen as Semitic or of mixed race, or he could be seen as maybe white.

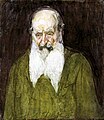

- Study of a Jewish man, circa 1899, that Tanner would rework throughout his lifetime. Thought to be used as a model for Nicodemus in Nicodemus Visiting Christ.

- Another version of Nicodemus, painted for the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition in 1909.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Nicodemus". Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art.

- ^ a b "Tanner's Exhibition". The Colorado Statesman. Vol. 15, no. 18. Denver. 23 January 1900.

All of Mr. Tanner's subjects are religious. As Harrison S. Morris says of him in the introduction to the catalogue, 'He has quietly followed his instinct for beauty, and employed it in the interpretation of the primitive characters and happenings of the Bible.' That 'instinct for beauty' shows itself especially in Mr. Tanner's moonlight scenes. When the artist visited Palestine he found that by day the scenery lacked atmosphere as the scenery of our western plains does; that its color was crude and hard...so he only painted it by night.

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9.

- ^ "A Negro Artist". The Macon Telegraph. Macon, Georgia. 2 January 1909. p. 4.

- ^ "An Afro-American Artist". Times Union. Brooklyn, New York. 13 September 1902. p. 15.

- ^ Holy Bible, King James Version, John 3:1-7

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9.

- ^ a b Harper, Jennifer J. (Autumn 1992). "The Early Religious Paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Study of the Influences of Church, Family, and Era". American Art. 6 (4). The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum: 69–72. doi:10.1086/424170. JSTOR 3109083. S2CID 191483607.

- ^ "Henry O. Tanner's Great Success in Religious Painting". The Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. 13 February 1909. p. 18.

Not since the enormous labors of Tissot in the Holy Land has there been such a series of portrayals of the life of the Saviour as this which has been so zealously carried out by Henry O. Tanner.

- ^ a b Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 17, 45. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9.

Because of this state of affairs, Tanner is frequently recognized purely as a painter of religious themes based on the fame of such uncontested masterpieces as The Resurrection of Lazarus and The Annunciation.

- ^ Special Exhibition: Religious Paintings by the Distinguished American Artist Mr. Henry O. Tanner. Madison Square South, New York: Madison Square Art Galleries. 1908.

No. 1 Night of the Nativity

No. 2 The Good Shepherd

No. 3 Moses and the Burning Bush

No. 4 "Behold the Bridegroom Cometh"

No. 5 Christ at the Home of Mary and Martha Loaned by the Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh

No. 6 Night (After the denial by Peter)

No. 7 The Wise Men

No. 8 Daniel in the Lions' Den

No. 9 Hebron

No. 10 The Two Disciples at the Tomb Loaned by the Art Institute of Chicago

No. 11 The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Sea

No. 12 Escape of Paul

No. 13 Death of Judas

No. 14 Christ and Nicodemus Loaned by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

No. 15 The Hiding of Moses

No. 16 Flight Into Egypt

No. 17 Judas Covenanting With the High Priest

No. 18 The Return of the Holy Woman Loaned by Mr. Rodman Wanamaker

No 19 "Mary Pondered All These Things in Her Heart" Loaned by Mr. Rodman Wanamaker

No. 20 Christ Washing the Disciples Feet Loaned by Mr. Rodman Wanamaker

No 21 Mary

No. 22 Hills Near Jerusalem Loaned by Rev. William B. Hill

No. 23 Nicodemus

No. 24 Head of an Old Jew

No. 25 Christ on the Road to Bethany

No. 26 He Vanished Out of Their Sight Loaned by Mr. and Mrs. Atherton Curtis

No. 27 Abraham's Oak Loaned by Mr. and Mrs. Atherton Curtis

No. 28 On the Road to Emmaus Loaned by Mr. and Mrs. Atherton Curtis

No. 29 The Flight Into Egypt Loaned by Mr. Daniel O'Day

No. 30 Jerusalem Types

No. 31 Jerusalem Types

No. 32 Jerusalem Types

No. 33 Jerusalem Types - ^ "Henry O. Tanner's Great Success in Religious Painting". The Winnipeg Tribune. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. 13 February 1909. p. 18.

None of his paintings that have been acquired by the French government could be made available...

- ^ a b c d e Cozzolino, Robert (2012). "8 "I Invited the Christ Spirit to Manifest in Me": Tanner and Symbolism". In Marley, Anna O. (ed.). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 129.

- ^ Helen Cole (June 1900). "Henry O. Tanner, Painter". Brush and Pencil. Vol. 6, no. 3. Chicago: Brush and Pencil Publishing Companey. p. 102.

Last year he showed "Nicodemus Coming to Christ," a moonlight scene, only the two figures, enveloped in a cold blue light, but the effect of night and remoteness and loneliness was exceedingly well rendered.

- ^ a b c d e Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9.

Despite these logical reasons for the play of light on Jesus, Tanner not only induces the viewer to accept all the illumination as deriving from the presence of Jesus but also emphasizes his spirituality without resorting to the use of a halo.

- ^ Fannie G. Thompson (11 February 1900). "The Opera and the Academy of Fine Arts Exhibition in Philadelphia". The Topeka Daily Capital. Topeka, Kansas. p. 13.

The picture which received the most valuable prize, offered by Mr. Walter Lippincott, is ...Henry O. Tanner's picture called "Nicodemus,"...It represents the visit of Nicodemus to Jesus by night. They are seated upon the house top in the dull, bluish light which is not moonlight and which is a triumph of technique. The stairs by which they ascended are at one side in the foreground of the picture and a faint yellow gleam as from a candle lights them up and casts a feeble ray upon the face of the Master. All else is in shadow. The figures are scarcely distinct enough to make any strong impression at first, but as they are studied the full meaning of this wonderful picture dawns upon us and we feel the power of that realism which is giving us In this new religious art a Christ more human than that of the old masters a man to be "touched with a feeling our infirmities."

- ^ Holy Bible, King James Version, John 3:19-21.

- ^ "Blacks in biblical antiquity". American Bible Society.

...it has become virtually axiomatic for people today to envision that somehow the ancient people of the New Testament were all Europeans. Without much reflection or critical analysis, people tend to project modern Jews back into antiquity as if two thousand years of assimilation never occurred.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants, 110:3.

His eyes were as a flame of fire; the hair of his head was white like the pure snow; his countenance shone above the brightness of the sun...

- ^ McFarlan, Emily (25 June 2020). "How an iconic painting of Jesus as a white man was distributed around the world". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The color of Christ: How has art affected racism in the Church?". The Daily Universe. Brigham Young University.

- ^ "Blacks in biblical antiquity". American Bible Society.

For the most part by modern standards of ethnicity, first-century Jews could be considered Afro-Asiatics. This is to say that Jesus, his family, his disciples and, doubtless, most of the fellow Jews he encountered in his public ministry, were persons of color. They would certainly not be Europeans...Mary and Joseph fled to Egypt to hide...it is difficult imagining, if the holy family were indeed persons who looked like typical "Europeans," that they could effectively "hide" in Africa.

- ^ Braddock, Alan C. (2012). "Christian Cosmopolitanism: Henry Ossawa Tanner and the Beginning of the End of Race". In Marley, Anna O. (ed.). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 136–138.

Tanner offered a powerful but now neglected alternative to racial thinking by envisioning Christ as a universal figure of humanity...a worldly cosmopolitan view of someone who transcended racial categories.

- ^ "Genius of this great man". The New York Age. New York, New York. 25 February 1909.

Wherever Christ figures in a picture it is noticeable that the artist cares less about showing the form and features of the man than the spirit.

- ^ a b "Son of Colored Bishop Wins Honor in Paris". The Tacoma Daily Ledger. Tacoma, Washington. 13 September 1908.

In Paris...no one regards me curiously. I am simply 'M. Tanner, an American artist.' Nobody knows nor cares what was the complexion of by forbears. I live and work there on terms of absolute social equality. Questions of race or color are not considered--a man's professional skill and social qualities are fairly and ungrudgingly recognized.

- ^ a b c Bruce, Marcus (2012). "7 A New Testament: Henry Ossawa Tanner, Religious Discourse and the "Lessons" of Art". In Marley, Anna O. (ed.). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 111.

Tanner's work was not color-blind, neutral, or void of the physical, cultural, geographical, national, or historical differences that often distinguish one group of people from another. His attention to skin color, facial feature, cultural clothing, indigenous architectural design, and geographical settings enabled him to offer realistic representations

- ^ Bearden, Romare; Henderson, Harry (Harry Brinton) (1993). A history of African-American artists : from 1792 to the present. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 100–101.

Some publications [in the United States] completely omitted mention fo Tanner because he was black. Others emphasized race, making that fact, rather than his achievments as an artist the reason for the attention.

- ^ Marley, Anna O., ed. (2012). Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 133.

[quoting:] Alan C. Bradock, "Painting the World's Christ: Tanner, Hybridity, and the Blood of the Holy Land," Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 2 (Autumn 2004)

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9.

The lack of articulation in the faces of the figures and the unemphasized Christ Child, who is seen only as a bundle of cloth on Mary's lap, allows one to see them as ordinary people drawn from the crowds that hurried toward Bethlehem. The biblical figures become timeless travelers, whose anxious journey gives them a universality that extends even to the African-American migrants of Tanner's time.

- ^ Bearden, Romare; Henderson, Harry (Harry Brinton) (1993). A history of African-American artists : from 1792 to the present. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 78–109.

drew and painted the heads of characteristic Hebraic and Arabic people...Tanner also made many sketches of traditional garments, recording their color combinations and the ways of wearing robes and burnooses.

- ^ Mosby, Dewey F. (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia; New York: Philadelphia Museum of Art; Rizzoli International Publications. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8478-1346-9.