Newark Liberty International Airport

Newark Liberty International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner/Operator | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | New York metropolitan area State of New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Newark, Essex County and Elizabeth, Union County, New Jersey, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | October 2, 1928 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||

| Operating base for | Spirit Airlines[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | EST (UTC−05:00) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−04:00) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°41′33″N 074°10′07″W / 40.69250°N 74.16861°W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||

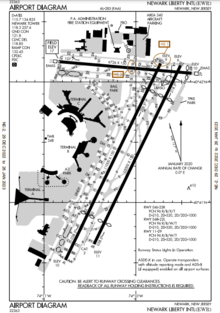

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Helipads | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2023) | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Newark Liberty International Airport[a] (IATA: EWR, ICAO: KEWR, FAA LID: EWR) is a major international airport serving the New York metropolitan area. The airport straddles the boundary between the cities of Newark in Essex County and Elizabeth in Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Located approximately 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of downtown Newark and 9 miles (14 km) west-southwest of Manhattan, it is a major gateway to destinations in Europe, South America, Asia, and Oceania. It is jointly owned by the two cities, and the airport itself is leased to its operator, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[4] It is the second-busiest airport in the New York airport system behind John F. Kennedy International Airport and ahead of LaGuardia Airport.

The airport is near the Newark Airport Interchange, the junction between both Interstate 95 and Interstate 78 (both of which are components of the New Jersey Turnpike), and U.S. Routes 1 and 9, which has junctions with U.S. Route 22, Route 81, and Route 21. AirTrain Newark connects the terminals with the Newark Liberty International Airport Railway Station. The station is served by NJ Transit's Northeast Corridor Line and North Jersey Coast Line. Amtrak's Northeast Regional and Keystone Service routes also make stops at the station.

The City of Newark built the airport on 68 acres (28 ha) of marshland in 1928, and the Army Air Corps operated the facility during World War II. The airport was constructed adjacent to Port Newark and U.S. Route 1. After the Port Authority took over the facility in 1948, an instrument runway, a terminal building, a control tower, and an air cargo center were constructed. The airport's Building One from 1935 was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

During 2022, the airport served 43.4 million passengers, which made it the 13th-busiest airport in the nation, and the 23rd-busiest airport in the world. The busiest year to date was 2023, when it served 49.1 million passengers. Newark Liberty International serves 50 carriers, and is the largest hub for United Airlines by available seat miles. The airline serves about 63% of passengers at EWR, making it the largest tenant at the airport. United and FedEx Express, its second-largest tenant, operate in three buildings covering approximately 2 million square feet (0.19 km2) of airport property.

History

In the 1920s, Newark, New Jersey, was the site of two airfields: Heller Field, which opened in 1919,[5] and Hadley Field, which opened in 1924,[6] that were used by the United States airmail service.

In May 1921, Heller Field was closed and all air mail services moved to Hadley Field, which by 1927 also served four airlines. The U.S. Postal Service, however, desired to have an airfield closer to New York City.[7] In 1927, people and organizations, both national and local in scope, began calling for a new airport in the area of Newark,[7][8][9][10] including Newark's mayor, Thomas Raymond.[11]

On August 3, 1927, Raymond ordered plans for a new airport.[12] Construction, which was estimated to cost $6 million (equivalent to $105,241,379 in 2023),[12][13] began on April 1, 1928, along US Route 1 and Port Newark.[14] The construction involved a land reclamation project to create 68 acres (28 ha) of level ground, 6 feet (1.8 m) above sea level to prevent flooding, upon which a 1,600-foot (490 m) runway was to be laid. In addition to the 6,735,000 cubic yards (181,800,000 cu ft; 5,149,000 m3) of earth required for the reclamation, 7,000 Christmas trees and 200 bank safes donated by a local junk vendor were used.[15]

The airport opened on October 1, 1928, dubbed the Newark Metropolitan Airport.[16] It was the first major airport to serve the New York metropolitan area,[17] the first commercial airport in the United States and the first with a paved airstrip.[18] The first lease for space at Newark Airport was signed by Canadian Colonial Airways in April 1928.[19][20]

The nation's first air traffic control tower and airport weather station opened at Newark in 1930.[21] The Art Deco style Newark Metropolitan Airport Administration Building, adorned with murals by Arshile Gorky,[22] was built in 1934 and dedicated by Amelia Earhart in 1935 and was the first passenger terminal in the United States.[23] It served as the terminal until the opening of the North Terminal in 1953.[24] Newark became the first airport to allow nighttime operations after installing runway lights in 1952.[21]

Construction of the Brewster Hangar began in 1937 and continued through 1938. This hangar was the most advanced of its time. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and is now a museum and Port Authority Police headquarters.[25][21]

Despite these innovations, critics said the airport was poorly designed because there was no separation of incoming and outbound passengers and no thought given to future expansion, though this did not stop Newark from being the busiest commercial airport. United Airlines, American Airlines, Eastern Airlines, and TWA signed 10-year leases with the airport which ended in 1938. Then they would pay on a month-to-month basis until LaGuardia Airport opened in December 1939;[26][27] by the middle of 1940, all passenger airlines had left Newark, no longer making it the world's busiest airport.[28]

World War II

When the United States joined World War II in late 1941, the field was closed to commercial aviation, and it was taken over by the United States Army for logistics operations.[29] The growing importance of supplying the overseas air forces and the need for more efficient control of supply shipments led to the activation of the Atlantic (and the Pacific) Overseas Air Service Commands on 1 October 1943. With headquarters at Newark, New Jersey (and Oakland, California for the Pacific Command). The Atlantic Overseas Air Service Command exercised control over the movement of Air Corps cargo through the ports of embarkation on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.[30][31][32]

In 1945, captured German aircraft brought from Europe on HMS Reaper for evaluation under Operation Lusty were off-loaded at Newark, and then flown or shipped to Freeman Field in Indiana, or Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland.

Reopened

The airlines returned to Newark in February 1946, when it was reopened to commercial service. In 1948, the city of Newark leased the airport to the Port of New York Authority, now the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. As part of the lease agreement, Port Authority took operational control of the airport and began investing heavily in capital improvements, including new hangars, a new terminal, and runway 4/22.[33]

On December 16, 1951, a Miami Airlines C-46 bound for Tampa, lost a cylinder on takeoff from runway 28 and crashed in Elizabeth, killing 56.[34] On January 22, 1952, an American Airlines CV-240 crashed in Elizabeth while on approach to Runway 6, killing all 23 aboard and seven on the ground.[35]

On February 11, 1952, a National DC-6 crashed in Elizabeth following takeoff from runway 24, killing 29 of 63 on board and four on the ground.[36][37]

Much of Newark Airport's traffic shifted to Idlewild, today known as John F. Kennedy International Airport, after Newark was temporarily closed in February 1952; flights were shifted to LaGuardia Airport and Idlewild, which allowed for planes to takeoff and land over the water rather than over the densely populated areas surrounding Newark Airport.[38] The airport remained closed in Newark until November 1952, with the introduction of new flight patterns that directed planes away from Elizabeth.[39] The continued unpopularity and the New York area's growing air traffic led to searches for new airport sites. Port Authority's proposal to build a new airport at what is now the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was defeated by local opposition.[40]

Through the early 1970s, Newark had a single terminal building located on the north side of the field by what is now Interstate 78.[41] A new control tower opened in 1960,[42] and the terminal was expanded from 26 to 32 gates in 1965.[43] A $200 million expansion of the airport, which was to include three terminals, began in 1967 after three years of planning.[44] In 1973, the airport was renamed Newark International Airport.[45] Former Terminal A and present Terminal B opened in 1973, although some charter and international flights requiring customs clearance remained at the North Terminal. The main building of Terminal C was completed at the same time, but only metal framing work was completed for the terminal's satellites. It would lay dormant until the mid-1980s, when, for a brief time, the western third of the terminal was readied for international arrivals and used for People Express transcontinental flights. Terminal C was then completed, and opened in June 1988.[46]

Underutilized in the 1970s, Newark expanded dramatically in the 1980s. People Express struck a deal with the Port Authority to use the North Terminal as its air terminal and corporate office in 1981 and began operations at Newark that April. It grew quickly, increasing Newark's traffic through the 1980s.[47] Virgin Atlantic began service between Newark and London in 1984, challenging JFK's status as New York's international gateway. Federal Express (now known as FedEx Express) opened its second hub at the airport in 1986.[48]

When People Express merged into Continental Airlines in 1987, operations (including corporate office operations) at the North Terminal were reduced, and the building was demolished to make way for cargo facilities in early 1997. This merger started the dominance of Continental Airlines, and later United Airlines, at Newark Airport.[49]

On July 22, 1981, a railroad tank car carrying ethylene oxide caught fire at the freight yard in Port Newark, causing the evacuation of a one-mile radius including an evacuation of the North Terminal building of the airport.[50]

In late 1996, the airport's monorail system opened, connecting the three terminals, the overflow parking lots and garages, and the rental car facilities. A new International Arrivals Facility also opened in Terminal B that year.[17] The monorail was expanded to the new Newark Airport train station on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor line in 2001, and was renamed AirTrain Newark.[51]

21st century

In 2000, the Port Authority moved the historic Building 51 and renamed it to Building One. The building, which weighs more than 7,000 short tons (6,200 long tons; 6,400 t), was hydraulically lifted, placed atop dollies and rolled about 0.75 miles (1.21 km). It is now where the airport's administrative offices are located.[21][52]

September 11 attacks

After the hijacking and subsequent crash of United Airlines Flight 93 during the 2001 September 11 attacks, the airport's name was changed from Newark International Airport to Newark Liberty International Airport in 2002. This name was chosen over the initial proposal, Liberty International Airport at Newark, and pays tribute to the victims of the September 11 attacks and to the landmark Statue of Liberty, lying 7 miles (11 km) east of the airport.[53][54]

On September 10, 2021, a new 9/11 memorial was dedicated at the historic former administration building, Building One. It features a steel base plate with a small piece of an exterior column from southwest corner of the South Tower of the former World Trade Center.[55]

International traffic expansion

In October 2015, Singapore Airlines announced intentions to resume direct nonstop service between Newark and its main hub at Changi Airport, which had ended in November 2013.[56] The airline announced that service would resume some time in 2018, and the Airbus A350-900ULR was chosen as the aircraft for the route.[57][58] On May 30, 2018, Singapore Airlines officially announced that nonstop service between Newark and Singapore would begin on October 11, 2018, and Newark Liberty once again became host to what was then the world's longest non-stop flight.[59][60]

Continental Airlines (now merged with United Airlines as of 2010) began flying from Newark to Beijing–Capital on June 15, 2005, and to Delhi on November 1, 2005. The airline soon started flights to Mumbai. On July 16, 2007, Continental announced it would seek government approval for nonstop flights between Newark and Shanghai–Pudong in 2009. Continental began flights to Shanghai from Newark on March 25, 2009, using a Boeing 777-200ER aircraft. Newark was the only airport in the New York City Metropolitan Area used by Philippine Airlines (PAL), until financial problems in the late 1990s compelled the airline to terminate this service.[61]

In June 2008, flight caps were put in place to restrict the number of flights to 81 per hour. The flight caps, in effect until 2009, were intended to be a short-term solution to Newark's congestion. After the cap expired, the FAA embarked on a seven-year-long project to reduce congestion in all three New York area airports, as well as the surrounding flight paths.[62]

Newark is a major hub for United Airlines (Continental Airlines before the 2010 merger). United has its Global Gateway at Terminal C, having completed a major expansion project that included a new, third concourse, and a new Federal Inspection Services facility. With its Newark hub, United has the most service of any airline in the New York area. On March 6, 2014, United opened a new 132,000-square-foot (12,300 m2), $25 million hangar on a 3-acre (1.2 ha) parcel to accommodate their wide-body aircraft during maintenance.[63] In 2015, the airline announced plans to leave JFK altogether and streamline its transcontinental operations at Newark.[64] On July 7, 2016, the United States Department of Transportation announced that Newark was one of ten cities to first operate flights to José Martí International Airport in Havana, Cuba.[65]

Southwest Airlines began service at the airport in 2011, flying to ten cities. It ended all Newark service in November 2019, primarily due to the Boeing 737 MAX groundings, low demand, and inadequate facilities, and consolidated its New York area operations to Long Island and LaGuardia.[66]

Redevelopment and growth

In 2016, the Port Authority approved and announced a redevelopment plan to replace Terminal A, set to fully open in 2022.[67] A $2.7 billion investment, the new terminal was expected to increase passenger flow and gate flexibility between airlines, and would also be accompanied by a replacement for the AirTrain Newark monorail system, scheduled for completion in 2024. The new Terminal A officially opened on December 8, 2022. The new Terminal A has 33 gates, increasing Newark's gate total to 125, including 16 international gates that can be alternated so that 2 narrow-body aircraft or 1 wide-body aircraft can occupy a space.[67][68]

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, which affected countless services across the New York City area, aircraft operations at Newark went though drastic changes, with only 15,892,892 passengers in 2020, despite having 46,336,452 the previous years, the most in its history.[69] Alaska Airlines trimmed its Newark schedule to three daily flights and leased their gates (A30 and A31) to JetBlue to accommodate their increased operations.[70] In June 2022, United Airlines announced they would cut about 50 domestic flights from Newark in an effort to reduce delays.[71][72] On January 11, 2023, the FAA system outage across the United States caused 103 flights from Newark to be grounded, the third highest in the country.[73]

In October 2022, PANYNJ announced their EWR Vision, which will cover short- and long-term development through 2065. Officials named Arup, a global top aviation planning and design firm, to partner with SOM, who has done several projects with the Port Authority and EWR prior.[74] The start of their plans included finishing the new Terminal A, which was successfully completed in January 2023,[68] and replacing the old AirTrain, which was expected to be completed sometime in 2026,[75] but later pushed to 2029.[76] Goals for the project include creating a World Class Gateway for New Jersey, creating long-term economic growth, and creating a phase-by-phase plan that will not affect the airport's operations, while simultaneously expanding it to accommodate passenger and cargo growth in that time.[77][74]

In October 2024, after extensive outreach to airport stakeholders, local community leaders and the public, PANYNJ unveiled the findings of the EWR Vision. Major elements of the EWR Vision Plan include:

- Terminal development: The plan calls for building a new, world-class international terminal to replace the current Terminal B, while enhancing Terminal C to improve the customer experience. Both would complement the airport’s award-winning new Terminal A that opened in January 2023, which could also see further expansion. The spacious, streamlined terminals would allow the airport to accommodate continued growth in passenger volume, while leaving space for further expansion as needed.

- Airside development: The plan envisions improving the airport’s operations with a more efficient and resilient taxiway network, while accommodating the industry trend toward larger aircraft. The new network would increase parking capacity and flexibility for aircraft, while creating redundancies to minimize delays during irregular operations. It incorporates additional deicing facilities, allowing aircraft to push off from gates more quickly. It would also include the industry’s latest safety standards, increasing straight taxiway segments and minimizing the need for crossings.

- Landside development: The blueprint looks to transform the airport’s vehicular and multi-modal access, prioritizing efficiency and convenience for all users. Alongside terminal buildings, frontages would be expanded to meet industry standards, providing ample space for passenger waiting, loading and unloading while minimizing walking distances. AirTrain access would be simplified, while connectivity and amenities for cyclists, pedestrians, and service vehicles would be improved. The roadway network would also be streamlined to reduce decision points and separate major flows with independent circulation for each terminal.

As of 2023, Newark serves 50 carriers and is the third-largest hub for United Airlines after Chicago O'Hare and Houston George Bush Intercontinental.[78] During a 12-month period ending in March 2022, over 63% of all passengers at the airport were carried by United Airlines. The second-busiest airline is JetBlue Airways, which carries 11.4%, followed by American Airlines, which carries 5.6%.[79] The second largest tenant is FedEx, which operates in 3 buildings on around two million square feet of the airport's property.[80]

Facilities

Runways and taxiways

The airport covers 2,027 acres (820 ha) and has three runways and one helipad:[81][82]

- 4L/22R: 11,000 by 150 feet (3,353 m × 46 m), asphalt/concrete, grooved

- 4R/22L: 10,000 by 150 feet (3,048 m × 46 m), asphalt, grooved

- 11/29: 6,726 by 150 feet (2,050 m × 46 m), asphalt, grooved

- Helipad H1: 54 by 54 feet (16 m × 16 m), asphalt

Runway 11/29 is one of the three runways built during World War II. In 1952, Runways 1/19 and 6/24 were closed and a new Runway 4/22 (now 4R/22L) opened at a length of 7,000 ft (2,100 m). After 1970, this runway was extended to 9,800 feet (3,000 m), shortened for a while to 9,300 ft (2,800 m) and finally reaching its present length by 2000. Runway 4L/22R opened in 1970 at a length of 8,200 ft (2,500 m) and was extended to its current length by 2000.[83]

The airport has more than 12 miles of 75-foot-wide taxiways. In 2014, the Port Authority completed a $97 million rehabilitation project of Runway 4L/22R while adding four new taxiways to reduce delays. Three of the new taxiways allow multiple planes to stage for departure at the end of the runway, reducing takeoff delays, while the other new taxiway will allow arriving planes to exit the runway faster and get to the gates quicker.[80][84]

All approaches except Runway 29 have Instrument Landing Systems and Runway 4R is certified for Category III approaches. Runway 22L had been upgraded to CAT III approach capability.[62]

Runway 4L/22R is primarily used for takeoffs while 4R/22L is primarily used for landings, and 11/29 is used by smaller aircraft or when there are strong crosswinds on the two main runways. Newark's parallel runways (4L and 4R) are 950 feet (290 m) apart, the fourth-smallest separation of major airports in the U.S., after San Francisco International Airport, Los Angeles International Airport, and Seattle–Tacoma International Airport.[49] Helipad H1 is used by Blade, a helicopter service that goes to EWR and JFK from their heliport on East 34th street in New York City with the purpose of going to and from the airport in under 5 minutes.[85][86] They use the Bell 407 helicopter.[87]

Unlike the other two major New York–area airports, JFK and LaGuardia, which are located directly next to large bodies of water (Jamaica Bay and the East River, respectively) and whose runways extend at least partially out into them, Newark Airport and its runways are completely land-locked. While located just across Interstate 95 from Newark Bay and not far from the Hudson River, the airport does not directly front upon either body of water.[88]

Cargo

In 1997, the North Terminal was torn down to make a new air cargo facility.[49] EWR now has almost 1 million square feet of total cargo facility space, and 290 acres (120 ha) are dedicated to cargo operations. The airport is in both Newark, Essex County and Elizabeth, Union County, and is adjacent to Port Newark–Elizabeth Marine Terminal and Foreign-Trade Zone No. 49. It serves more than 45 air carriers with nearly 1,200 daily arrivals and departures to domestic and international destinations. Climate-controlled warehouse areas and cold storage accommodate perishable items.[80][89]

Aeroterm operates buildings 339 and 340, and the designated United Airlines cargo facility was constructed in 2001. The FedEx Cargo Complex is a $60-million sort facility at its Newark Hub which includes Buildings 347, 156 and most of 155. Building 157 is a cargo building used by several tenants. Construction of it was completed in 2003. UPS completed construction of their new cargo building in 2019.[80]

Air traffic control

In December 1935, the airport's first air control station came into existence following a flight that crashed outside of Kansas City, killing five people, including a U.S. senator. The airport's original terminal, or Building 51, also known as the Administration Building housed the first air traffic control tower for the airport, and was designed by John Homlish in the 1930s.[52][90][91] A concrete brutalist-styled and toothbrush-shaped control tower was built in 1960, and opened on January 18 of that year, designed by architect Allan Gordon Lorimer;[92] the cost of the construction was estimated to be $1.5 million.[93] In 2002, this control tower closed and was replaced by a new and taller control tower, and was demolished in 2004. The current air traffic control tower is 325 feet tall (99 m).[94] The current tower is located next to a Marriott hotel, which is located on the airport's property.[95][96] The current tower overlooks the Manhattan Skylines and the George Washington Bridge.[97]

Other facilities

There are several hotels adjacent to Newark Liberty International Airport. Hotels such as Courtyard by Marriott and the Holiday Inn are located on the airport's property.[98][99] Signature Flight Support is the only fixed-base operator at the airport, providing various services to private aircraft.[100] Terminals A, B, and C all have short-term parking lots. Garage P4 can access the AirTrain directly. Economy Parking P6 can be accessed from the terminals using the Port Authority shuttle bus.[101] An Exxon gas station with a 7-Eleven store (both with street address 100 Lindbergh Road) is located on the airport's property.[102][103]

Terminals

Across the airport's three terminals, there are 125 gates: Terminal A has 33 gates, Terminal B has 24 gates, and Terminal C has 68 gates.[104]

Gate numbering starts in Terminal A with Gate A1 and ends in Terminal C at C138. Wayfinding signage throughout the terminals was designed by Paul Mijksenaar, who also designed signage for LaGuardia and JFK Airports.[105]

Terminal A

In March 2017, the Port Authority approved the project to build a new Terminal A, replacing the original terminal, which opened in 1973.[106] Built on a site once occupied by United Parcel Service and the United States Postal Service,[67] the new terminal cost around $2.7 billion and includes redesigned roadways with 8 new bridges, a new six-level, 2,700-car parking garage and rental center,[107][108] 33 gates, and a walkway to connect the AirTrain station, parking garage, and terminal building.[108] The terminal officially opened on December 8, 2022.[68][109] However, due to continued testing of the fire alarm and security system as well as a hesitance from the PANYNJ to open a brand new terminal ahead of the 2022 holiday season, the grand opening was delayed to January 12, 2023, at which 17 of the total 33 gates opened – all on the south side of the terminal.[110] The rest of the 33 gates opened in August 2023.[111]

Designed by Grimshaw Architects, Terminal A references the modern era design of the "modular concrete structures" of the other two terminals through the use of the latest materials that allow for a larger and more light filled space.[112][113] The redevelopment offers more traffic lanes at pickup and drop-off points, closer check-in counters and security areas to the entrance, and more gate flexibility to allow planes to park at any gate in a "common-use" system.[107][67] The new Terminal A has four levels: the departures level, the mezzanine level for offices, the arrivals level, and the ground floor, where baggage claim is located.[67] The terminal is operated as EWR Terminal One LLC by Munich Airport International, a subsidiary of Munich Airport, which manages the terminal's operations, maintenance, and concessions in the 1 million square feet of retail space.[114] The redevelopment also comes with plans to replace the existing AirTrain monorail system, scheduled to open in 2029, and was not opened along with the new Terminal A.[67]

The new Terminal A handles flights by Air Canada, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, JetBlue (except for international arrivals from non-precleared flights which are handled at Terminal B), and a minority of United flights not in Terminal C.[115] Multiple technologies in the terminal, such as check-in and security, have been partly-automated.[115] The terminal's design has been noted for its use of art from local artists, art on digital columns, a new variety of restaurants and stores, and easy access to power outlets. The terminal was designed to fit New Jersey's "Garden State" (the state's nickname) image.[112] The new terminal also has a designated section for ridesharing company pickups, public transportation, and taxis.[115][68] On top of the new Terminal A parking garage, the Port Authority built a rooftop canopy of 12,708 solar panels that is the size of six football fields and the largest solar roof at any airport in the United States.[116] In 2023, Terminal A was awarded the special prize for an exterior in the world selection for the 2023 Prix Versailles in the airports category.[117] In 2024, Skytrax awarded Terminal A their prestigious 5-star rating and named it the best new airport terminal in the world. Terminal A is only the second terminal in North America to achieve both awards.[118][119]

Terminal B

Terminal B, like the original Terminal A, was completed in 1973 and has four levels. Terminal B is the only passenger terminal directly operated by the Port Authority. It handles most foreign carriers, such as British Airways, Lufthansa, and Aer Lingus, ultra-low cost regional operators like Spirit Airlines, Sun Country Airlines, and Allegiant Air, and some of United's international arrivals.[120]

In 1996, a new $120 million internationals arrival hall opened. The hall is the length of two football fields and features large skylights and windows allowing for natural light and panoramic views of flight activity and the Manhattan skyline. It features 56 immigration booths and seven baggage carrousels.[121]

In 2006, Terminal B renovations began to increase capacity for departing passengers and passenger comfort. The renovations included expanding and updating the ticketing areas, building a new departure level for domestic flights and building a new arrivals hall.[122] In January 2012, Port Authority executive director Patrick Foye said $350 million would be spent on Terminal B, addressing complaints by passengers that they cannot move freely. The renovations enhanced the terminal's "cathedral-like layout" and made the terminal more cohesive while adding more than 1,000,000 sq ft (93,000 m2) of usable space.[123] Further developments were made to Terminal B when the Port Authority installed new LED fixtures in 2014. The LED fixtures, developed by Sensity Systems, use wireless network capabilities to collect and feed data into the software that can spot long lines, recognize license plates, and identify suspicious activity and alert the appropriate staff.[124] The full renovation of Terminal B was complete by May 2014.[123]

The original Terminal B building is slated for demolition and replacement with new terminal to be constructed landslide.[125][126][127][128]

Terminal C

Terminal C, designed by Grad Associates,[129] was completed in 1988. Terminal C is exclusively operated by and for United Airlines and its regional carrier United Express for their global hub. The main terminal building for Terminal C was built alongside Terminals A and B in the 1970s, but lay dormant until People Express Airlines took it over as a replacement for the former North Terminal when the airline's hub there outgrew the old facility.[130]

From 1998 to 2003, Terminal C was rebuilt and expanded in a $1.2 billion program known as the Continental Airlines Global Gateway Project.[131][132] The project, which was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill,[131] doubled the available space for outbound travelers as the former baggage claim/arrivals hall was remodeled and turned into a second departures level.

International Concourse C-3, a new facility with capacity for a maximum of 19 narrow-body aircraft (or 12 wide-body planes), was added as well.[131] Completion of this new concourse increased Terminal C's mainline jet gates to 57. Accompanying Concourse C-3 was a new international arrivals facility.[132] Also included in the project were an airside corridor connecting Concourses C-1, C-2, and C-3, a President's Club (now United Polaris Lounge) for international business class passengers between C-2 and C-3, and new baggage processing facilities, including reconstruction of the former underground parking area into a new baggage claim and arrivals hall.[133][134]

In November 2014, airport amenity manager OTG announced a $120 million renovation plan for Terminal C that included installing 6,000 iPads and 55 new restaurants headed by celebrity chefs, with the first new restaurants opening in summer of 2015 and the whole project completed in 2016.[135] In 2019, Terminal C was named 'Best for Foodies' in the nation by Fodor's Travel Awards.[136]

Former terminals

North Terminal (1953–1997)

The North Terminal opened in 1953.[24] Former Terminal A and present Terminal B opened in 1973, although some charter and international flights requiring customs clearance remained at the North Terminal prior to the opening of two new terminals.[46] Following significant expansion at EWR, People Express Airlines made a deal with the Port Authority to use the North Terminal as its air terminal and corporate office in 1981 and began operations at Newark that April.[47] When People Express merged with Continental Airlines in 1987, operations at the North Terminal were reduced. In 1997, the North Terminal was closed and then demolished making place for new cargo facilities.[49]

Terminal A (1973–2023)

The original Terminal A opened in 1973 and was closed on January 12, 2023, when the new Terminal A opened. It was operated by EWR Terminal One LLC, part of Flughafen München GmbH. Terminal A handled only domestic and Canadian flights served by JetBlue (for domestic flights), Air Canada, Air Canada Express, American Airlines,[137] American Eagle; and some United Express flights.[138][139]

In Terminal A, there was one United Club in Terminal A's second concourse (A2). It also had an Admirals Club for American Airlines and an Air Canada Maple Leaf Lounge.[140] Terminal A was the only terminal that had no immigration facilities; flights arriving from other countries could not use Terminal A without U.S. customs preclearance, although some departing international flights used the terminal.[141] In 2016, the Port Authority approved and announced a redevelopment plan to build a new Terminal A replacing this one.[142]

Part of Terminal A was closed for demolition on September 30, 2021.[143] The remainder of the former Terminal A was closed to the public, and replaced with the new Terminal A on January 12, 2023.[144] As of late spring, 2024, the majority of the terminal has been demolished, with only the headhouse remaining and being used as the home of the Newark Airport Redevelopment Office.[145]

Ground transportation

Train

A monorail system, AirTrain Newark, connects the terminals with Newark Liberty International Airport Station. The station is served by New Jersey Transit's Northeast Corridor Line and North Jersey Coast Line, with connections to regional rail hubs such as Newark Penn Station, Secaucus Junction and New York Penn Station where transfers are available to any rail line in northern New Jersey or Long Island, New York. Amtrak's Northeast Regional and Keystone Service trains also stop at the Newark Liberty International Airport station. Passengers can ride the AirTrain for free between the terminals and the parking lots, parking garages, and rental car facilities.[146]

In September 2012, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced that work would commence on a study to explore extending the PATH system to the station.[147] The new station would be located at ground level to the west of the existing NJ Transit station.[148]

In 2014, the Board of Commissioners approved a formal proposal to extend the PATH to Newark Airport.[149] On January 11, 2017, the Port Authority released its 10-year capital plan that included $1.7 billion for the extension. Under the plan, construction was projected to start in 2020, with service in 2026.[150][151] As of April 2023, the plan for the station was changed to prioritize providing access from the station to the surrounding neighborhood with preliminary design and planning work for the station expansion underway. The PATH train extension is "being differed to a future capital plan" due to a "current funding shortfall".[152] On March 22, 2024, the Port Authority approved the $160 million station expansion project that will construct a pedestrian bridge from the station to a plaza off of Frelinghuysen Avenue accessible to pedestrians and cyclists with a drop off area for people coming by car or bus. The project no longer includes an extension of the PATH train but will preserve a right of way in case the line is ever extended. The project is scheduled to be completed in 2026.[153]

In January 2019, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy announced a plan for a $2 billion replacement project for AirTrain Newark. Murphy stated that replacement is necessary because the system is reaching the end of its projected 25-year life and is subject to persistent delays and breakdowns. The Port Authority would be responsible for funding the project.[154] In October 2019, the Port Authority board approved the replacement project with an estimated cost of $2.05 billion.[155] On May 5, 2021, the Port Authority issued requests for proposals to four teams.[156] In December 2023, the Port Authority announced that the Austrian company Doppelmayr had been awarded the contract to replace the existing train system with a modern cable car system. The contract includes operating costs for 20 years and is close to $1 billion. The new AirTrain is scheduled to open in 2029.[157]

Bus

NJ Transit

NJ Transit buses operate northbound local service to Irvington, Downtown Newark and Newark Penn Station, where connections are available to the PATH and NJ Transit rail lines. The go bus 28 is a bus rapid transit line to Downtown Newark, Newark Broad Street Station and Bloomfield Station. Southbound service travels to Elizabeth, Lakewood, Toms River and intermediate points.[158][159] NJ transit also operates bus routes 37, 62, 67, 107 and 107X to EWR.[160]

Olympia Trails

Olympia Trails operates express buses to the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Bryant Park, and Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan,[161] Super-Shuttle and Go-link operate shared taxi services as GO Airport Shuttle.[162][163][164]

Trans-Bridge Lines

United Airlines' bus service and Trans-Bridge Lines offer shuttles to Lehigh Valley International Airport (ABE) in Hanover Township, Pennsylvania outside Allentown.[165] Continental Airlines, (which later merged into United in 2010), previously operated flights from Newark to Allentown, but switched to a bus service in 1995 due to constant delays from air traffic control.[166]

Trans-Bridge Lines operates buses to EWR on their Allentown-Clinton-New York City eastbound and westbound route using both ABE and the Allentown Bus Terminal in Allentown, Clinton's Park and Ride, and Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan with several stops in Lehigh and Northampton counties.[167][168]

Road

Private limousine, car service, and taxis also provide service to/from the airport. For trips to and from New York City, fares are set by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission.[169]

The airport is served directly by U.S. Route 1/9, which provides connections to Route 81 and Interstate 78, both of which have interchanges with the New Jersey Turnpike at Interstate 95's exits 13A and 14, respectively. The interchange where U.S. Route 1/9, U.S. Route 22, New Jersey Route 21, Interstate 78, and Interstate 95 meet is known as the Newark Airport Interchange.[170] Northbound, Route 1/9 becomes the Pulaski Skyway, which connects to Route 139. Route 139 continues east to the Holland Tunnel, which links Jersey City with Lower Manhattan.[171]

The airport's northern, eastern, and western perimeters are directly surrounded by Brewster Road, a two-lane road which primarily serves to connect to the North area, South area, Port Authority police, and most parking lots.[172] The airport's official address is 3 Brewster Road.[173]

The airport operates short and long term parking lots with shuttle buses and monorail access to the terminals. The Port Authority's electric shuttle bus fleet comprising 36 buses and 19 chargers, was completed in October 2020 at Newark, John F. Kennedy International, and LaGuardia airports.[174] A free cellphone lot waiting area is available for drivers picking up passengers at the airport.[175]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

^1 : Ethiopian Airlines's flight from Addis Ababa to Newark stops at Rome–Fiumicino,[233] but the flight from Newark to Addis Ababa is nonstop.

Cargo

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,071,000 | JetBlue, Spirit, United | |

| 2 | 1,048,000 | Alaska, JetBlue, Spirit, United | |

| 3 | 868,000 | Alaska, JetBlue, United | |

| 4 | 814,000 | JetBlue, Spirit, United | |

| 5 | 750,000 | Delta, JetBlue, Spirit, United | |

| 6 | 737,000 | American, Spirit, United | |

| 7 | 687,000 | American, JetBlue, Spirit, United | |

| 8 | 557,000 | Spirit, United | |

| 9 | 521,000 | American, Spirit, United | |

| 10 | 514,000 | American, Spirit, United |

| Rank | Change | Airport | Passengers | Change | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 789,380 | British Airways, United | |||

| 2 | 575,941 | El Al, United | |||

| 3 | 466,472 | JetBlue, United | |||

| 4 | 426,001 | Lufthansa, United | |||

| 5 | 405,047 | Air Canada, United | |||

| 6 | 370,251 | JetBlue, United | |||

| 7 | 368,055 | Porter | |||

| 8 | 367,699 | JetBlue, United | |||

| 9 | 366,639 | TAP Air Portugal, United | |||

| 10 | 323,826 | JetBlue, United |

Airline market share

Carrier shares (December 2022 - November 2023)

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United Airlines | 33,414,010 | 68.1% |

| 2 | Spirit Airlines | 2,804,033 | 5.7% |

| 3 | JetBlue | 2,375,540 | 4.8% |

| 4 | American Airlines | 2,355,794 | 4.8% |

| 5 | Delta Air Lines | 1,771,602 | 3.6% |

| 6 | Alaska Airlines | 1,146,730 | 2.3% |

| 7 | Air Canada | 751,197 | 1.5% |

| 8 | Scandinavian Airlines | 465,860 | 1.0% |

| 9 | Porter Airlines | 410,390 | 0.8% |

| 10 | British Airways | 384,655 | 0.8% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 34,188,701 | 2010 | 33,194,190 | 2020 | 15,892,892 |

| 2001 | 31,100,322 | 2011 | 33,697,492 | 2021 | 29,049,552 |

| 2002 | 29,220,775 | 2012 | 33,983,435 | 2022 | 43,565,254 |

| 2003 | 29,450,514 | 2013 | 35,015,058 | 2023 | 49,084,774 |

| 2004 | 31,893,372 | 2014 | 35,543,757 | 2024 | |

| 2005 | 33,079,244 | 2015 | 37,496,727 | 2025 | |

| 2006 | 35,634,708 | 2016 | 40,563,293 | 2026 | |

| 2007 | 36,367,210 | 2017 | 43,219,121 | 2027 | |

| 2008 | 35,360,736 | 2018 | 45,859,520 | 2028 | |

| 2009 | 33,360,123 | 2019 | 46,389,037 | 2029 |

Airport information

Newark Airport, along with LaGuardia and JFK airports, uses a uniform style of color-coded signage throughout the airport properties, designed by Paul Mijksenaar.[105][246] Former New York City traffic reporter Bernie Wagenblast provides the voice for the airport's radio station and curbside announcements, as well as the messages heard onboard AirTrain Newark and in its stations.[247][248] The airport has the IATA airport code EWR, rather than a designation that begins with the letter 'N' because the designator of "NEW" is already assigned to Lakefront Airport in New Orleans. Also, the Department of the Navy uses three-letter identifiers beginning with N for its purposes.[249]

Accidents and incidents

- On March 17, 1929, a Colonial Western Airlines Ford Tri-Motor suffered a double engine failure during its initial climb after takeoff, failed to gain height, and crashed into a railroad freight car loaded with sand, killing 14 of the 15 people on board. At the time, it was the deadliest aviation accident in American history.[250]

- On January 14, 1933, Eastern Air Transport, a Curtiss Condor, crashed at Newark; two crewmembers were killed.[251]

- On May 4, 1947, Union Southern Airlines, a Douglas DC-3 with 12 passengers and crew, crashed on landing at Newark after overrunning the runway and into a ditch where it burned. Two crewmembers were killed.[252]

- On December 16, 1951, a Miami Airlines C-46 Commando (converted for passenger use) lost a cylinder on takeoff from Runway 28 and crashed in Elizabeth, killing 56.[34]

- On January 22, 1952, American Airlines Flight 6780, a Convair 240, crashed in Elizabeth on approach to Runway 6, killing 30.[35]

- On February 11, 1952, National Airlines Flight 101, a Douglas DC-6, crashed in Elizabeth after takeoff from Runway 24, killing 33.[37][253]

- On April 18, 1979, a New York Airways commuter helicopter on a routine flight to LaGuardia Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport plunged 150 feet (46 m) into the area between Runways 4L/22R and 4R/22L, killing three passengers and injuring 15. It was later determined the crash was due to a failure in the helicopter's tail rotor.[254]

- On March 30, 1983, a Learjet 23 operated by Hughes Charter Air, a night check courier flight, crashed on landing at EWR during an unstabilized approach. Both crewmembers were killed. Marijuana was later found in their systems, believed to have impaired judgement.[255]

- On July 31, 1997, FedEx Flight 14, a McDonnell Douglas MD-11, crashed while landing after a flight from Anchorage International Airport. The Number 3 engine contacted the runway during a rough landing, which caused the aircraft to flip upside down. The aircraft was destroyed by fire. The two crewmembers and three passengers escaped uninjured.[256][257]

- In the September 11 attacks, United Airlines Flight 93 took off from Newark Airport bound for San Francisco. It was hijacked by four al-Qaeda terrorists and diverted towards Washington, D.C., with the intent of crashing the plane into either The Capitol building or the White House. After learning about the previous attacks on the World Trade Center and The Pentagon, the passengers attempted to retake control of the plane. The passengers then forced the hijackers to crash the plane into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. After that, an American flag flew over Gate A17, the gate that Flight 93 took off from.[258] Terminal A was demolished in 2022, but the jet bridge for Gate A17 has been preserved. In April 2022, the jetway (referred to as Jetway 17) was moved to its new home at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center headquarters in Glynco, Georgia.[259]

- On May 1, 2013, Scandinavian Airlines Flight 908, an A330-300 that was cleared for takeoff, collided with an ExpressJet Embraer ERJ-145 aircraft on the taxiway. The ERJ-145 lost its tail in the accident.[260]

See also

Notes

- ^ Originally Newark Metropolitan Airport and later Newark International Airport.

References

- ^ "Spirit Airlines, Inc. - News". ir.spirit.com.

- ^ "General Information". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "EWR (KEWR): NEWARK LIBERTY INTL, NEWARK, NJ - UNITED STATES". Aeronautical Information Service. Federal Aviation Administration. December 30, 2021. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ "Property owned and leased by the Port Authority" (PDF). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. January 16, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- ^ "First Mail Leaves Air Terminus Here". Newark Evening News. December 8, 1919. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Lurie & Mappen 2004, p. 342.

- ^ a b Holden 2009, p. 7.

- ^ "Airport Rivalry, New York and Newark". Courier-Post. July 2, 1927. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Edge Feeling His Way About Field". The News. July 11, 1927. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "An Airport Needed". The Record. July 14, 1927. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "North Jersey Busy Seeking Air Ports". Courier-Post. August 2, 1927. p. 14. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Newark Airport Plans Ordered". New York Daily News. August 4, 1927. p. 175. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Holden 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Holden 2009, pp. 15, 63.

- ^ Holden 2009, pp. 7, 16, 19.

- ^ Lurie & Mappen 2004, p. 12.

- ^ a b "Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR)". baruch.cuny.edu. Archived from the original on June 11, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Sforza, Daniel (September 28, 2003). "Newark Airport at 75: The Sky's The Limit". The Record. ProQuest 425600892.

- ^ Holden 2009, pp. 7–8.

- ^ "Canadian Air Line Gets Space". The New York Times. ProQuest 102886458. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Port Authority's National Historic Landmark Building One Rededicated At Newark Liberty International Airport". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. December 17, 2002. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ Comenas, Gary. "Abstract Expressionism: Arshile Gorky's Newark Airport Murals". Warholstars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "PORT AUTHORITY'S NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK BUILDING ONE REDEDICATED AT NEWARK LIBERTY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. December 17, 2002. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "Newark's New Air Terminal". The New York Times. July 29, 1953. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Newark Metropolitan Airport". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ Holden 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Holden 2009, p. 47.

- ^ "City Airport Opens Officially Tonight". The New York Times. December 1, 1939. p. 25. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Holden 2009, p. 74: "As early as 1939, thousands of fighter planes were flown from manufacturing plants to Newark Airport where they were partially disassembled and shipped overseas on transport ships out of Port Newark. The air technical service command at Newark Airport averaged 40 flights and 50,000 pounds of air cargo daily. In all, over 51,000 aircraft were shipped from Newark during World War II, primarily to the European theater of operations. (NJAHOF.)"

- ^ The Army Air Forces in World War II: Europe, torch to pointblank, August 1942 to December 1943. Office of Air Force History. 1948. ISBN 978-0-912799-03-2.

The control of rail and water transportation for all U.S. Army forces in the theater had been vested in the Services of Supply, but the Eighth Air Force, in keeping with the general AAF trend toward autonomy, tended to win an increasing responsibility for the reception and distribution of its own supplies. [In a similar development in the United States late in 1942 the Air Service Command established the New York Air Service Port Area Command which became in 1943 the Atlantic Overseas Air Service Command, with headquarters at Newark. This organization controlled all air service activities at the port and provided an important link between Patterson Field and the VIll Air Force Service Command.] (p. 615)

- ^ The Army Air Forces in World War II: Men and planes. Office of Air Force History. 1948. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-912799-03-2.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under This work is the product of the United States government. Text taken from The Army Air Forces in World War II: Men and planes

Volume 6 of The Army Air Forces in World War II, United States. Air Force. Office of Air Force History, 369, Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate, United States. Air Force. Office of Air Force History, United States. Air Force. Air Historical Group, United States. USAF Historical Division, Office of Air Force History.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under This work is the product of the United States government. Text taken from The Army Air Forces in World War II: Men and planes

Volume 6 of The Army Air Forces in World War II, United States. Air Force. Office of Air Force History, 369, Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate, United States. Air Force. Office of Air Force History, United States. Air Force. Air Historical Group, United States. USAF Historical Division, Office of Air Force History.

- ^ Holden 2009, pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b "Driscoll Demands Stricter Air Curbs; Says Crash That Killed 56 Shows the Need for Controls". The New York Times. December 19, 1951. p. 37. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "Pilot Was on Instrument-Guided Approach; Ground Control 'Talks' Flier Off Course". The New York Times. January 23, 1952. p. 20. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Hyman, Vicky (May 29, 2015). "How three planes crashed in three months in Elizabeth in '50s". NJ.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Accident Investigation Report, National Airlines, Inc., Elizabeth, New Jersey, February 11, 1952 (Report). Civil Aeronautics Board. May 16, 1952. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ "Newark Airport Stays Closed Pending Results of Inquiries; Safety Group Headed by Rickenbacker Set Up by U.S. and Airlines -- Take-Offs Over Water Pledged at La Guardia, Idlewild; Airport Closed Pending Inquiry", The New York Times, February 13, 1952. Accessed March 27, 2023. "With La Guardia and New York International (Idlewild) Airports in Queens taking over the bulk of Newark's former flights for the time being, it was also agreed to use their runways so as to enable planes to take off over water or over least-settled areas as much as possible.... The agreements were announces at the Commodore Hotel after a closed-door conference of five and a half hours, called by the Port of New York Authority as a result of three airplane crashes in Elizabeth, N.J., which have taken 116 lives in the last two months and which caused closing of Newark Airport early Monday morning."

- ^ Sharkey, John B. "Newark Liberty International Airport, A Postal History", New Jersey Postal History Society, May 2021. Accessed March 27, 2023. "The airport reopened on November 15, 1952, but only after a new runway was built. The runway directed at the city of Elizabeth was closed forever."

- ^ Holden 2009, p. 82.

- ^ "EWR72". Departed Flights. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ "Control Tower Opened at Newark". The New York Times. January 19, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ Appel, Fredric C. (June 28, 1965). "Newark Airport Expands Plane Facilities to Ease Traffic Congestion; Congestion Takes Many Forms at Newark Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ Burrows, William E. (October 9, 1967). "Newark Airport Grows, but Still Lags; Expansion to Begin at Newark Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "For Dumping Grounds In Meadows A Mighty Airport Has Developed". newspapers.com. September 13, 1973. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Holden 2009, p. 10.

- ^ a b Avery, Brett (February 5, 2008). "30 and Counting: People Express". New Jersey Monthly. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Airlines Airport Guide" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Holden 2009, p. 120.

- ^ People Exp. Airlines, Inc. v. Consolidated Rail, 100 N.J. 246 (N.J. 1985)

- ^ "AirTrain History". PANYNJ. Archived from the original on February 19, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "Newark Liberty International Airport". Beyer Blinder Belle. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Michael (August 22, 2002). "Governors Seek a Name Change for Newark Airport". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ Smothers, Ronald (August 30, 2002). "Port Authority Extends Lease of a Renamed Newark Airport". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (September 10, 2021). "From a maintenance worker's idea, Port Authority 9/11 monument has blossomed". NJ Advance Media. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Singapore Airlines Ends Airbus A340-500 Service from late-Oct 2013". Routes Online. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (October 15, 2015). "The longest non-stop flight in the world is returning to Newark". NJ.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ "World's Longest Non-Stop Flight Returns To N.J. Airport". Patch.com. October 15, 2015. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ Zhang, Benjamin. "Singapore Airlines will relaunch the world's longest flight, which will cover more than 10,000 miles and last 19 hours". Yahoo! Finance. New York. Archived from the original on May 31, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018 – via Business Insider.

- ^ Andrew (January 12, 2022). "Singapore Airlines goes triple daily to New York, with the return of non-stop Newark flights". Mainly Miles. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "PAL to Fly to NY, Major US Cities". The Inquirer. April 11, 2014. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "New York Area Program Integration Office (NYAPIO) Delay Reduction Plan (DRP) | Federal Aviation Administration". faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (March 6, 2014). "United Airlines throws open its new hangar doors at Newark airport". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ "United Airlines Strengthens New York/New Jersey Hub with Move of p.s. Transcontinental Service to Newark" (Press release). United Airlines. June 16, 2015. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Newman, Richard; Alvarado, Monsy (July 7, 2016). "Newark among 10 cities chosen for daily flights to Havana". North Jersey Media Group. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ Goldman, Jeff (July 25, 2019). "Southwest Airlines to cease flights from Newark airport". NJ.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Lynn, Kathleen (December 17, 2019). "Preparing for Takeoff: A Sneak Peek at Newark Airport's New Terminal". New Jersey Monthly. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Peterson, Barbara (January 12, 2023). "Newark Airport's Seriously Upgraded New Terminal A Is Now Open". AFAR. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ 2019 Annual Airport Traffic Report (PDF). United States: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ "EWR". AlaskaAir. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Josephs, Leslie (June 23, 2022). "United Airlines will cut 12% of Newark flights in effort to tame delays". CNBC. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Potter, Kyle (June 24, 2022). "United Will Cut 50 Flights a Day Out of Newark This Summer". Thrifty Traveler. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Quinn, Liam (January 11, 2023). "Flights resume at Newark Airport after FAA technical issues ground flights nationwide". northjersey.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Higgs, Larry (October 24, 2022). "Master Planners Named to Guide Newark Airport's Redevelopment Through 2065". nj.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (August 17, 2021). "Feds OK plans to replace Newark airport's aging monorail". nj.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Mike Hayes (December 15, 2023). "Newark airport's monorail system is getting an upgrade". Gothamist. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ "EWR Vision Plan". ewrredevelopment.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Mutzabaugh, Ben (January 26, 2017). "The fleet and hubs of United Airlines, by the numbers". USA Today. New York: Gannett. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Airport Traffic Statistics". New York: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Air Cargo Newark Liberty Airport". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on February 24, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for EWR PDF, effective November 28, 2024.

- ^ "EWR airport data at skyvector.com". skyvector.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Holden 2009, p. 75.

- ^ "New Taxiways At Newark Liberty International Airport Will Help Reduce Flights Delays As Part Of A Nearly $100 Million Project To Over Longest Runway" (Press release). New York: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Get to the airport in 5 minutes". BLADE. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ "BLADE Airport - Where We Fly". BLADE. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ "Fly on a Bell 407 Helicopter with BLADE Airport". BLADE. Archived from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ^ "Trans World Airlines Flight Center (now TWA Terminal A) At New York International Airport" (PDF). s-media.nyc.gov. July 19, 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "New York City (NYC) Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) - Statistics 2003-2017". Baruch City University of New York. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Young, Michelle (September 10, 2019). "A Gorgeous Art Deco Terminal is Hidden in Newark Airport". Untapped Cities. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Lauria-Blum, Julia (February 11, 2022). "Metropolitan Airport Icons - New York Aviation History". Metropolitan Airport News. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ Architectural League of New York; American Craftsmen's Council; American Crafts Council (1960). 1960 National gold medal exhibition of the building arts Achievement in the building arts. New York. p. 72. OCLC 1087486694. Retrieved February 8, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Control Tower Opened at Newark". The New York Times. January 19, 1960. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Liberty Airport Control Tower". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ "Newark Liberty International Airport Marriott". Marriott.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "FAA Traffic Control Tower" (PDF). LVI Services. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Frassinelli, Mike (December 6, 2009). "Newark air traffic controller feels vindicated after speaking out against safety concerns". NJ.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "Newark Liberty International Airport Marriott". Marriott. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Holiday Inn Newark International Airport". IHG. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Signature EWR Fixed Base Operator". Signature Flight Support. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Parking Lots - EWR - Newark Liberty Airport". Newark Liberty International Airport. Archived from the original on February 24, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ 7-ELEVEN, 100 LINDBERGH RD, NEWARK NJ 07114

- ^ "Station detail". www.exxon.com.

- ^ "Airport Guide – Newark Liberty International Airport". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "A full information system for New York Airports". Mijksenaar. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Kiefer, Eric (December 7, 2017). "$2B Newark Airport Project Gets Big Chunk Of Funds Approved". Patch.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ a b Gibbons, Megan (January 18, 2023). "New Terminal Opens At Newark Airport That Will Serve Over 13 Million Passengers A Year". Travel Off Path. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Cornerstone Of Redevelopment For EWR". ewrredevelopment.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Higgs, Larry. "New $2.7B Newark Airport Terminal A is ready for takeoff. Here's a look inside". MSN. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (December 5, 2022). "Opening of Newark airport's new Terminal A delayed until January". NJ.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Coleen. "Heading to Newark Liberty? All 33 gates are now open at the new Terminal A". northjersey.com. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ a b "Newark Liberty International Airport Terminal A". Grimshaw Architects. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ Bzdak, Meredith (June 18, 2018). "Newark Liberty International Airport to lose an important piece of its Modern heritage". Docomomo. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ "Leading global airport operator to manage new 2.7 billion dollars Terminal One at Newark Libert". Munich Airport. July 16, 2019. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Chang, Brittany (January 14, 2023). "I went inside Newark's new $3 billion Terminal A that completely transforms the airport — see what it was like". Business Insider. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "At 6 football fields long, this solar-powered N.J. airport building is the biggest in the U.S." NJ Advance Media. April 21, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "2023 World Awards Airports". Prix Versailles. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ "Newark airport just won an award that's like the Michelin star of air travel". NJ Advance Media. March 19, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Newark airport's new $2.7B terminal won another global award". NJ Advance Media. April 19, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Newark Airport Terminal B (EWR)". Newark Airport. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Newark Airport Is Pressing to Surpass Kennedy". The New York Times. January 24, 1996. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Building a Better Airport". Newark Airport. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Richards, Jodi (June 2014). "Top-To-Bottom Renovations Breathe New Life Into Newark Liberty". Airport Improvement. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Cardwell, Diane (February 17, 2014). "At Newark Airport, the Lights Are On, and They're Watching You". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ "$55M to Advance Planning for New Terminal B at EWR". New Jersey Business Magazine.

- ^ "More Newark Airport Redevelopment Set with Terminal B Rebuild Plan Unveiled | Engineering News-Record". www.enr.com.

- ^ Gainer, Alice (October 17, 2024). "Newark Airport's new Terminal B renderings unveiled - CBS New York". www.cbsnews.com.

- ^ "PORT AUTHORITY UNVEILS PLAN TO REIMAGINE NEWARK LIBERTY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AS WORLD-CLASS GATEWAY, CHARTING COURSE FOR ADDITIONAL MODERN TERMINALS, STREAMLINED ROADWAY AND MORE EFFICIENT RUNWAYS". www.panynj.gov.

- ^ Read, Philip (March 25, 2010). "Architectural Firm That Shaped Newark, N.Y.C. Skylines Closes After 104 Years". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (April 27, 2002). "Slow Return as Hub for Aviation; After 67 Years, Newark's First Terminal Has New Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Newark Liberty International Airport – old Continental Airlines Terminal C3 Expansion". Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ a b "Continental Airlines Global Gateway Project". Binsky. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "United Polaris Lounge EWR". LoungeBuddy. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "EWR Polaris Lounge". Newark Long Term Parking. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Green, Dennis (November 19, 2014). "Newark Airport Is Undergoing A Massive Renovation – Here's What It Will Look Like Inside". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ King, Rebecca. "Named 'Best for Foodies': Newark Airport Terminal C dining guide". northjersey.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "Newark International Airport (EWR) Admirals Club, Terminal A". aa.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Baskas, Harriet (June 28, 2021). "Everything You Need to Know About Traveling Through Newark Airport". Travel + Leisure. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "Newark Airport Terminal A". Newark Airport. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "Servic US". mapleleafclub.ca. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Newark Airport Terminals Guide". Newarklongtermparking.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ "Port Authority has $6B plan for new airport terminals". NJ.com. March 23, 2016. Archived from the original on March 10, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "Port Authority Moves Forward With Next Phase In Newarl Liberty International Airport's $2.7 Billion Terminal Replacement". The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "New Terminal A - Newark Liberty International Airport". Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "Why an old terminal at Newark Airport and a defunct N.Y.C. tunnel toll plaza are still standing". NJ Advance Media. September 8, 2024. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ "New Jersey Transit". njtransit.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "Port Authority To Undertake Study On Extending Path Rail Service To Newark Liberty International Airport" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. September 20, 2012. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "PATH Extension Project PUBLIC SCOPING MEETINGS National Environmental Policy Act" (PDF). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. November 28, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (February 4, 2014). "Port Authority unveils 10-year capital plan, includes $27.6B in projects". nj.com. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "PANYNJ Proposed Capital Plan 2017-2026" (PDF). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Reitmeyer, John (May 1, 2017). "What's the Plan for PATH Service to Newark Liberty Airport? - NJ Spotlight". NJ Spotlight News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (March 14, 2023). "New rail station to be built ahead of delayed PATH Newark Airport extension". nj.com. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ "Start OK'd for $160M project linking parts of Newark and Elizabeth to AirTrain, NJ Transit". NorthJersey.com. March 22, 2024. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Reitmeyer, John (January 23, 2019). "Murphy Wants to Replace Newark Airport Monorail, No More 'Bubblegum' Fixes". NJ Spotlight News. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (May 6, 2021). "Companies vying to complete $2B replacement of Newark Airport monorail". NJ.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Newark Liberty's New World-Class, 21st Century AirTrain Project Advances with a Request for Proposals Issued to Four Shortlisted Teams" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. May 5, 2021. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Mike Hayes (December 15, 2023). "Newark airport's monorail system is getting an upgrade". Gothamist. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ "How to Get from Toms River to Elizabeth by Bus, Night Bus, or Car". Rome2rio. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Go Bus 28". NJ Transit. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Newark Liberty International Airport". NJ Transit. Archived from the original on November 29, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ "Newark Airport Express". Coach USA. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Newark Liberty Airport Transportation". GO Airport Shuttle. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "Newark Airport Shuttle Service". GO Airlink NYC. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "SuperShuttle". SuperShuttle Express. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "FAQ's: Bus to EWR". ABE. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ Karp, Gregory (May 4, 2010). "Airlines merger could halt bus flight". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ "town / Clinton / New York Route-Eastbound" (PDF). transbridgelines.com. December 12, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2022. Retrieved August 30, 2022.

- ^ "Allentown / Clinton/ New York-Westbound" (PDF). transbridgelines.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Taxi Fare". NYC TLC. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Lapolla, Micheal (2005). The New Jersey Turnpike. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738535777. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Boyle Plaza Dedicated". The New York Times. May 6, 1936. p. 26. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Newark International Airport, Brewster Hangar, Brewster Road between Route 21 & New Jersey Turnpike Exchange No. 14, Newark, Essex County, NJ". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Driving directions to 3 Brewster Rd, 3 Brewster Rd, Newark". Waze. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Port Authority Doubles Electric Shuttle Bus Fleet at Airports, Becoming the Largest All-Electric Fleet on the East Coast" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. October 15, 2020. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Cell Phone Lot". Newark Airport. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Timetables". Aer Lingus. Dublin: International Airlines Group. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "Aeromexico NW24 US Network Additions". Aeroroutes. Retrieved July 22, 2024.