1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes

The Great Earthquake at New Madrid, a 19th-century woodcut from Devens' Our First Century (1877) | |

| UTC time | 1811-12-16 08:15:00 |

|---|---|

| 1811-12-16 13:15:00 | |

| 1812-01-23 15:15:00 | |

| 1812-02-07 09:45:00 | |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| ComCat | |

| ComCat | |

| ComCat | |

| Local date | December 16, 1811 |

| December 16, 1811 | |

| January 23, 1812 | |

| February 7, 1812 | |

| Local time | 02:15 |

| 07:15 | |

| 09:15 | |

| 03:45 | |

| Magnitude | |

| Mw 7.5[1] | |

| Mw 7.0[2] | |

| Mw 7.3[3] | |

| Mw 7.5[4] | |

| Max. intensity | MMI XII (Extreme) |

| Aftershocks | Mw 6.3,[5] 6.3,[6] 6.1[7] & 6.3[8] |

| Casualties | Unknown[9] |

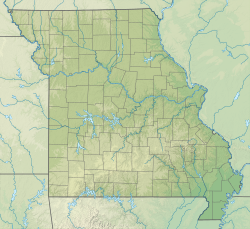

The 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes were a series of intense intraplate earthquakes beginning with an initial earthquake of moment magnitude 7.2–8.2 on December 16, 1811, followed by a moment magnitude 7.4 aftershock on the same day. Two additional earthquakes of similar magnitude followed in January and February 1812. They remain the most powerful earthquakes to hit the contiguous United States east of the Rocky Mountains in recorded history.[10][11][12] The earthquakes, as well as the seismic zone of their occurrence, were named for the Mississippi River town of New Madrid, then part of the Louisiana Territory and now within the U.S. state of Missouri.

The epicenters of the earthquakes were located in an area that at the time was at the distant western edge of the American frontier, only sparsely settled by European settlers. Contemporary accounts have led seismologists to estimate that these stable continental region earthquakes were felt strongly throughout much of the central and eastern United States, across an area of roughly 50,000 square miles (130,000 km2), and moderately across nearly 1 million sq mi (3 million km2). The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, by comparison, was felt moderately over roughly 6,200 sq mi (16,000 km2). The earthquakes were interpreted by Tecumseh's pan-Indian alliance, to mean that Tecumseh and his brother the Prophet must be supported.[13]

Events

- December 16, 1811, 08:15 UTC (02:15 am local time): M 7.2–8.2,[11][12] epicenter in what is now northeast Arkansas. It caused only slight damage to man-made structures, mainly because of the sparse population in the epicentral area. The future location of Memphis, Tennessee, experienced level IX shaking on the Mercalli intensity scale. A seismic seiche propagated upriver, and Little Prairie (a village that was on the site of the former Fort San Fernando, near the site of present-day Caruthersville, Missouri) was heavily damaged by soil liquefaction.[12] Modified Mercalli intensity VII or greater was observed over a 600,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) area.[14]

- December 16, 1811 (aftershock), 13:15 UTC (07:15 am local time): M 7.4,[12] epicenter in southeast Missouri. This shock followed the first earthquake by six hours and was similar in intensity.[11]

- January 23, 1812, 15:15 UTC (09:15 am local time): M 7.0–8.0,[11][12] epicenter in the Missouri Bootheel. The meizoseismal area was characterized by general ground warping, ejections, fissuring, severe landslides, and caving of stream banks. Johnston and Schweig attributed this earthquake to a rupture on the New Madrid North Fault. This may have placed strain on the Reelfoot Fault.[12]

- February 7, 1812, 09:45 UTC (03:45 am local time): M 7.4–8.6, epicenter near New Madrid, Missouri. The town of New Madrid was destroyed. In St. Louis, Missouri, many houses were severely damaged and their chimneys were toppled. This shock was definitively attributed to the Reelfoot Fault by Johnston and Schweig. Uplift along a segment of this reverse fault created temporary waterfalls on the Mississippi at Kentucky Bend, created waves that propagated upstream, and caused the formation of Reelfoot Lake by obstructing streams in what is now Lake County, Tennessee.[12] The maximum Modified Mercalli intensity observed was XII.[15]

The many more aftershocks include one magnitude 7 aftershock to the December 16, 1811, earthquake which occurred at 6:00 UTC (12:00 am local time) on December 17, 1811, and one magnitude 7 aftershock to the February 7, 1812, earthquake which occurred on the same day at 4:40 UTC (10:40 pm local time).[12] Susan Hough, a seismologist of the United States Geological Survey, has estimated the earthquakes' magnitudes as around magnitude 7.[16]

| Date | Time (UTC) | Magnitude Mw | Location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 16 | 08:15:00 | 7.5 | Northeast Arkansas | [1] |

| December 16 | 09:00:00 | 6.3 | Near New Madrid, Missouri | [5] |

| December 16 | 13:15:00 | 7.0 | Western Tennessee | [2] |

| December 16 | 18:00:00 | 6.3 | Near New Madrid, Missouri | [6] |

| December 17 | 18:00:00 | 6.1 | Near Memphis, Tennessee | [7] |

| January 23 | 15:00:00 | 7.3 | North of New Madrid, Missouri | [3] |

| February 7 | 09:45:00 | 7.5 | Western Tennessee | [4] |

| November 9 | 22:00:00 | 4.0 | New Madrid, Missouri area | [18] |

Eyewitness accounts

John Bradbury, a fellow of the Linnean Society, was on the Mississippi on the night of December 15, 1811, and describes the tremors in great detail in his Travels in the Interior of America in the Years 1809, 1810 and 1811, published in 1817:[19]

After supper, we went to sleep as usual: about ten o'clock, and in the night I was awakened by the most tremendous noise, accompanied by an agitation of the boat so violent, that it appeared in danger of upsetting ... I could distinctly see the river as if agitated by a storm; and although the noise was inconceivably loud and terrific, I could distinctly hear the crash of falling trees, and the screaming of the wild fowl on the river, but found that the boat was still safe at her moorings. By the time we could get to our fire, which was on a large flag in the stern of the boat, the shock had ceased; but immediately the perpendicular banks, both above and below us, began to fall into the river in such vast masses, as nearly to sink our boat by the swell they occasioned ... At day-light we had counted twenty-seven shocks.

Eliza Bryan[20] in New Madrid, Territory of Missouri, wrote the following eyewitness account in March 1812:

On the 16th of December 1811, about two o'clock, a.m., we were visited by a violent shock of an earthquake, accompanied by a very awful noise resembling loud but distant thunder, but more hoarse and vibrating, which was followed in a few minutes by the complete saturation of the atmosphere, with sulphurious vapor, causing total darkness. The screams of the affrighted inhabitants running to and fro, not knowing where to go, or what to do—the cries of the fowls and beasts of every species—the cracking of trees falling, and the roaring of the Mississippi— the current of which was retrograde for a few minutes, owing as is supposed, to an irruption in its bed— formed a scene truly horrible.

John Reynolds, the fourth governor of Illinois, among other political posts, mentions the earthquake in his biography My Own Times: Embracing Also the History of My Life (1855):[21]

On the night of the 15th of December 1811, an earthquake occurred, that produced great consternation amongst the people. The centre of the violence was in New Madrid, Missouri, but the whole valley of the Mississippi was violently agitated. Our family all were sleeping in a log cabin, and my father leaped out of bed crying aloud "the Indians are on the house" ... We laughed at the mistake of my father, but soon found out it was worse than the Indians. Not one in the family knew at the time that it was an earthquake. The next morning another shock made us acquainted with it, so we decided it was an earthquake. The cattle came running home bellowing with fear, and all animals were terribly alarmed on the occasion. Our house cracked and quivered, so we were fearful it would fall to the ground. In the American Bottom many chimneys were thrown down, and the church bell in Cahokia sounded by the agitation of the building. It is said the shock of an earthquake was felt in Kaskaskia in 1804, but I did not perceive it. The shocks continued for years in Illinois, and some have experienced it this year, 1855.

The Shaker diarist Samuel Swan McClelland described the effects of the earthquake on the Shaker settlement at West Union (Busro), Indiana, where the earthquakes contributed to the temporary abandonment of the westernmost Shaker community.[22]

Geologic setting

The underlying cause of the earthquakes is not well understood, but modern faulting seems to be related to an ancient geologic feature buried under the Mississippi River alluvial plain, known as the Reelfoot Rift. The New Madrid seismic zone is made up of reactivated faults that formed when what is now North America began to split or rift apart during the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia in the Neoproterozoic era (about 750 million years ago). Faults were created along the rift, and igneous rocks formed from magma that was being pushed towards the surface. The resulting rift system failed to split the plate, but has remained as an aulacogen (a scar or weak zone) deep underground.

In recent decades, minor earthquakes have continued.[23] The epicenters of over 4,000 earthquakes can be identified from seismic measurements since 1974, originating from the seismic activity of the Reelfoot Rift. Forecasts for the next 50 years estimate a 7–10% chance of a major earthquake like those of 1811–1812, and a 25–40% chance of a quake of magnitude 6 or greater.[24]

In a report filed in November 2008, the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency warns that a serious earthquake in the New Madrid Seismic Zone could inflict "the highest economic losses due to a natural disaster in the United States", further predicting "widespread and catastrophic" damage across Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and particularly Tennessee, where a 7.7 or greater magnitude quake would cause damage to tens of thousands of structures affecting water distribution, transportation systems, and other vital infrastructure.[25]

Aftermath

The quakes caused extensive changes to the region's topography. Subsidence, uplift, fissures, landslides and riverbank collapses were common. Trees were uprooted by the intense shaking; people drowned when subsided land flooded. Reelfoot Lake was formed in Tennessee by subsidence of 1.5 meters to 6 meters in some places. Lake St. Francis in eastern Arkansas was expanded by subsidence, with sand and coal being ejected from fissures in the adjacent swamps as water levels rose by 8 to 9 meters. Waves on the Mississippi River caused boats to wash ashore; river banks rose, sand bars were destroyed, and some islands completely disappeared.[26] Sand blows occurred in Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas, covering farmland.

The continuous underlying rock mass, uninterrupted by fractures or faults, conducted the seismic waves from the earthquakes over great distances, with perceptible ground shaking as far away as Canada.[27] Intense effects were widely felt in Illinois, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri.

The number of people who died is unknown; as a frontier area, the region was sparsely populated, and communications and records were poor. The predominantly wooden buildings resisted collapse,[27] though the intense shaking caused many chimneys to fall, wood structures to crack, and trees to fall on buildings,[26] particularly in the epicentral area during the first earthquake on December 16, 1811.[26]

Rated at VII on the Mercalli Intensity Scale, the New Madrid earthquakes remain the strongest recorded North American earthquakes east of the Rocky Mountains.[26][27] The earthquakes strengthened the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa after the defeat at the Battle of Tippecanoe and the destruction of Prophetstown, with local Native Americans seeing it as a vindication of his teachings and of the warnings of his brother Tecumseh.[28]

Gallery

- Reelfoot Rift and NMSZ

- Damage-range comparison between a moderate New Madrid zone earthquake (1895, magnitude 6.8), and a similar Los Angeles event (1994, magnitude 6.7).

See also

References

- ^ a b "M 7.5 – Northeastern Arkansas (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ a b "M 7.0 – Western Tennessee (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "M 7.3 – North of New Madrid, Missouri (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ a b "M 7.5 – Western Tennessee (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ a b "M 6.3 – Near New Madrid, Missouri (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "M 6.3 – Near New Madrid, Missouri (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "M 6.1 – Near Memphis, Tennessee". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "M 6.3 – Near Marked Tree, Arkansas". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ O.W. Nuttli (1974). "The Mississippi Valley earthquakes of 1811 and 1812". Earthquake Information Bulletin (USGS). 6 (2). United States Geological Survey: 8–13. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Geological Survey: Largest Earthquakes in the United States". Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Historic Earthquakes New Madrid Earthquakes 1811–1812 United States Geological Survey Archived June 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Enigma of the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812. Johnston, A. C. & Schweig, E. S. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Volume 24, 1996, pp. 339–384. Available on SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS)

- ^ John Ehle (1988). Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 102–4. ISBN 978-0-385-23954-7. (Page numbers may be for a different printing.)

- ^ "Summary of 1811-1812 New Madrid Earthquakes Sequence". United States Geological Survey. October 2, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ National Earthquake Information Center. "M 7.8 – Western Tennessee (New Madrid Seismic Zone)". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Richard A. Lovett, Quake analysis rewrites history books, Nature News, April 29, 2010.

- ^ "NMSZ, 1810-1815". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "M 4.0 – New Madrid". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ [1]Bradbury, John (1817). Bradbury's Travels in the interior of America, 1809–1811. Applewood Books. pp. 199–207. ISBN 978-1-4290-0055-0.

- ^ Letter of Eliza Bryan found in Lorenzo Dow's Journal, Published By Joshua Martin, Printed By John B. Wolff, 1849, p. 344. Accessed September 17, 2009. Archived September 21, 2009.

- ^ Reynolds, John (1855). My own times: embracing also the history of my life. B. H. Perryman and H. L. Davison. p. 125. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ^ Diary of Samuel Swan McClelland, in "Shakers of Eagle and Straight Creeks," Shakers of Ohio: Fugitive Papers Concerning the Shakers of Ohio, with unpublished manuscripts, J. P. MacLean, ed. Columbus, Ohio, 1907.

- ^ Schweig, Eugene; Gomberg, Joan; Hendley, James W. II (1995), "The Mississippi Valley-"Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On"", Fact Sheet, USGS Fact Sheet: 168-95, United States Geological Survey, doi:10.3133/fs16895, hdl:2027/uc1.31210010703609

- ^ "USGS Release: Scientists Update New Madrid Earthquake Forecasts". United States Geological Survey. January 13, 2003. Retrieved November 8, 2008.

- ^ Carey Gillam (November 20, 2008). "Government warns of 'catastrophic' U.S. quake". Reuters. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Summary of 1811-1812 New Madrid Earthquakes Sequence". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c "New Madrid earthquakes of 1811–12 | United States | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Cozzens, Peter (2021). The Warrior and the Prophet: The Epic Story of the Brothers Who Led the Native American Resistance.

Further reading

- Jay Feldman. When the Mississippi Ran Backwards : Empire, Intrigue, Murder, and the New Madrid Earthquakes Free Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-7432-4278-3

- Conevery Bolton Valencius, The Lost History of the New Madrid Earthquakes The University of Chicago Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-2260-5389-9

- Conevery Bolton Valencius, "Accounts of the New Madrid earthquakes: personal narratives and seismology over the last two centuries," in Deborah R. Coen, ed., "Witness to Disaster: Earthquakes and Expertise in Comparative Perspective," *Science in Context*, 25, no. 1 (February 2012): 17–48.

- Viitanen, Wayne (1973), "THE WINTER THE MISSISSIPPI RAN BACKWARDS: Early Kentuckians Report the New Madrid, Missouri, Earthquake of 1811–12", The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 71 (1): 51–68, JSTOR 23377345

External links

- The Enigma of the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812. Johnson, A.C. and Schweig, E.S. (1996) Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Volume 24, pp. 339–384. SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS)

- The Introduction to The Lost History of the New Madrid Earthquakes by Conevery Bolton Valencius.

- The New Madrid Fault Zone (NMFZ) Archived December 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (links to maps, history, predictions, etc. from the Arkansas Center for Earthquake Education)

- Steamboat Adventure: The New Madrid Earthquakes (dozens of contemporary accounts of the earthquake, provided by Hanover College)

- USGS, Summary of 1811-1812 New Madrid Earthquake Sequence, at https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/earthquake-hazards/science/summary-1811-1812-new-madrid-earthquakes-sequence?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

- [2] The "Hard Shock:" The New Madrid Earthquakes. The History Guy