Neoplasticism

Piet Mondriaan: Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue, 1935 | |

| Years active | 1917–1924 |

|---|---|

| Location | The Netherlands |

| Major figures | Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg, Bart van der Leck, Vilmos Huszár, Georges Vantongerloo, Robert van 't Hoff, Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

Neoplasticism (or neo-plasticism), originating from the Dutch Nieuwe Beelding, is an avant-garde art theory proposed by Piet Mondrian[a] in 1917 and initially employed by the De Stijl art movement. The most notable proponents of this theory were Mondrian and another Dutch artist, Theo van Doesburg.[1] Neoplasticism advocated for a purified abstract art, by applying a set of elementary art principles. Thus, a painting that adhered to neoplastic art theory would typically consist of a balanced composition of simple geometric shapes, right-angled relationships and primary colors.[2]

Terminology

The term 'plastic arts' comes from the Greek word plastikos, which means "to mold or shape". This word perfectly describes the nature of plastic arts, which involve the use of materials that can be molded or shaped.[3]

Le Néo-Plasticisme[4]

Mondrian, Van der Leck and Van Doesburg first set out the philosophical basis for the art theory known originally as "Nieuwe Beelding", but known today as "Neoplasticism", in a new art journal named De Stijl [The Style].[5] The term appears in an editorial by Van Doesburg in the first issue of the journal[6] and in the first of a series of articles by Mondrian entitled De Nieuwe Beelding in de schilderkunst.[7][b] The expression "nieuwe beelding" is believed to derive from the work of Mathieu Schoenmaekers, who used the term in his 1915 book Het Nieuwe Wereldbeeld,;[8][9] copies of books by Schoenmaekers were found in Mondrian's library.[10]

Introducing their translation of Mondrian's publications, Holtzman and James wrote:

The Dutch verb beelden and substantive beelding signify form-giving, creation, and by extension image – as do gestalten and Gestaltung in German, where Neo-Plastic[ism] is translated as Die neue Gestaltung. The English plastic and the French plastique stem from the Greek plassein, [meaning] to mold or to form, but do not quite encompass the creative and structural signification of beelding.[11]

Some authors have translated nieuwe beelding as new art.[12][2]

The term néo-plasticisme [neo-plasticism] first appeared in Mondrian's Le Néo-plasticisme: Principe Général de l'Equivalence Plastique,[13] [Neo-plasticism: the general principle of plastic equivalence].[14][c] Mondrian described the essay as a "condensed adaptation of the ideas in his Trialogue".[14][d] The book was translated into French with the help of Mondrian's old friend, Dr Rinus Ritsema van Eck. In the 1925 German edition – the fifth in the Bauhaus Bauhausbücher series (translated by Rudolf F. Hartogh) – the term néo-plasticisme is translated as Neue Gestaltung [New Design].[20][21]

Between 1935 and 1936, Mondrian wrote an essay in French, translated into English with the help of Winifred Nicholson and published in the book Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art as "Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art (Figurative Art and Non-Figurative Art)".[22] After moving to the United States, Mondrian wrote several articles in English with the help of Harry Holtzman and Charmion von Wiegand, in which he maintained the use of the term 'plastic'.[23]

In his book "De Stijl", Paul Overy reflects on the confusing terminology for English readers:[24]

The terms beeldend and nieuwe beelding have caused more problems of interpretation than any others in the writing of Mondrian and other De Stijl contributors who adopted them. These Dutch terms are really untranslatable, containing more nuances that can be satisfactorily conveyed by a single English word. Beeldend means something like ‘'image forming'’ or ‘'image creating'’; nieuwe beelding means ‘'new image creation'’, or perhaps new structure. In German, the term nieuwe beelding is translated as neue Gestaltung, which is close in its complexity of meanings to the Dutch. In French, it was rendered as néo-plasticisme, later translated literally into English as Neo-Plasticism, which is virtually meaningless. This has been further confounded by the editors of the collected English edition of Mondrian's writings, who adopted the absurd term "the New Plastic".[24]

Notwithstanding this critique, Victoria George provides a succinct explanation of Mondrian's terminology:

What Mondrian called 'the New Plastic' was named as such because 'plastic' signified "that which creates an image".[25] It was New because its terms of reference had not been encountered before in painting. The image, that is, 'the Plastic', cleansed of superficialities and references to the natural world, is the New Plastic in Painting.[26]

Neoplastic theory

According to neoplastic principles,[27][28] every work of art (painting, sculpture, building, piece of music, book, etc.,) is created intentionally. It is the product of a series of aesthetic choices and, to a lesser extent, of what the work of art represents. For example, the event depicted in the painting Et in Arcadia ego, by Nicolas Poussin, never took place. Even though the postures of the figures are unnatural, it is convincing and forms a harmonious whole.[27][28]

Every artist manipulates reality to produce an aesthetically and artistically pleasing harmony. The most realistic painters, such as Johannes Vermeer or Rembrandt van Rijn, use all kinds of artistic means to achieve the greatest possible degree of harmony.

The artists of De Stijl called these 'visual means' "beeldend" (plastic). However, the artist determines to what extent he allows these 'plastic means' to dominate or whether he remains as close as possible to his subject. There is therefore a duality in painting and sculpture – and to a lesser extent in architecture, music and literature – between the idea of the artist and the matter of the world around us.[29][30]

The Dutch neo-plasticists, imbued with Calvinism[31] and Theosophy,[32] preferred the universal over the individual, the spiritual over the natural, the abstract over the real, the non-figurative over the figurative, the intuitive over the rational; all of which were summarised by Mondrian as the superiority of pure plastic over the plastic.[24][33][34] The neo-plasticists of De Stijl expressed their vision (plastic) in terms of 'pure' elements, not found in nature: straight lines, right angles, primary colours and precise relationships. This disassociation from nature created a new art, whose essential qualities were spiritual, entirely abstract, and rational.[35]

Idea versus Matter

In his Principles of Neo-Plastic Art,[36][37] Van Doesburg distinguishes between two types of visual art in art history: works that arise from an internal idea (ideo-plastic art), and works that arise from external matter (physio-plastic art).[38] He demonstrates this with an abstract model of the Egyptian god Horus and a realistic statue of a Diadumenos respectively. When an artist experiences reality, his aesthetic experience can be expressed as either a material depiction, or an abstract formation. Van Doesburg regards depiction as an 'indirect' form of artistic expression; only abstract formation based on an artist's true aesthetic experience of reality represents a pure form of artistic expression, as expressed by Mondrian in all his essays.[39][40][24]

Visual resources

According to the new visual art, every work of art consists of a number of basic elements, which they called 'visual means'. According to the artists of De Stijl, these 'visual means', unlike representation, are entirely inherent to art. If one wanted to produce a work of art 'according to art', one had to use only these basic elements. Mondrian wrote:

If the pure visual expression of art lies in the proper transformation of the plastic means and their application – the composition – then the plastic means must be in complete accord with what they express. If they are to be a direct expression of the universal, then they cannot be other than universal i.e. abstract.[41]

While Mondrian limited himself to painting, Van Doesburg believed in the collaboration of all arts to achieve a new Gesamtkunstwerk [total work of art]. To achieve this, it was necessary for each art form to establish its own 'visual means'. Only then was the independence of each art form guaranteed.[42] In 1920 he arrived at the following definition:

The painter, the architect, the sculptor and the furniture maker each realize that they have only one essential visual value: harmony through proportion. And everyone expresses this one essential and universal value of visual art with his or her art medium. One and the same but in a different way. The painter: through colour ratio. The sculptor: by volume ratio. The architect: by ratio of enclosed spaces. The furniture designer: through unenclosed (= open) space relationships.[43]

Synthesis

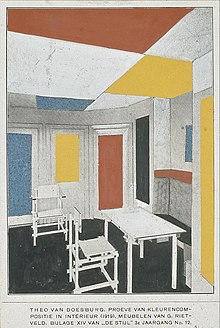

The artists of De Stijl strove for more and better cooperation between the arts without each art form losing its independence. The reason for this was what they saw as the architect's role being too great. The greatest results were expected from the collaboration between the architect and the painter. It was then the painter's task to 'recapture' the flat surface of architecture. Van Doesburg wrote about this:

Architecture provides constructive, therefore closed, plastic. In this she is neutral towards painting, which provides open plasticity through flat colour representation. In this respect, painting is neutral towards architecture. Architecture joins together, binds together. Painting loosens, dissolves. Because they essentially have to perform a different function, a harmonious connection is possible.[44]

In 1923, following the De Stijl architectural exhibition in Paris, Van Doesburg also involved the 'unenclosed (= open) space relationship' of furniture art on architecture. He subsequently regarded architecture as a 'synthesis of new visual expression'. 'In the new architecture, architecture is understood as a part, the summary of all the arts, in its most elementary appearance, as its essence', according to Van Doesburg.[45]

Background

Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian

Although countless artists embraced and applied the ideas of neoplasticism during the interwar period, its origins can mainly be attributed to Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian. They have worked to publicize their ideas through a stream of publications, exhibitions and lectures. Moreover, from 1917 to 1924 they were the constant factors in the otherwise quite turbulent history of the Style Movement. Their views on art were so close that some works by Van Doesburg and Mondrian are almost completely interchangeable. Van Doesburg's widow, Nelly van Doesburg, commented: "I further remember that Mondriaan and 'Does' once made a painting together, with the express intention that all traces of the individual share would be removed".[46]

Differences of opinion appeared between the two as early as 1919, however in 1922 there was a rift in their relationship over the application of neo-plastic principles to architecture and Van Doesburg's integration of the element of time into Mondrian's neo-plastic theory. [47]

Theosophy

When Van Doesburg and Mondrian first made public their ideas about the New Plastic art, both painters were influenced by theosophy.[48] Mondrian wrote the first theoretical treatise in his then hometown Laren, North Holland. Here he met the theosophist-author Mathieu Schoenmaekers. Mondrian adopted some of Schoenmaekers' terminology, including the Dutch term beeldend.[49][e] Van Doesburg and Mondrian's ideas about the spiritual come from Kandinsky's autobiography Über das geistige in der Kunst [On the spiritual in art] published in 1911. Mondrian remained interested in theosophy until his death. Van Doesburg distanced himself from theosophy around 1920 and focused on quasi-scientific theories such as the fourth dimension and what he called 'mechanical aesthetics' (design by mechanical means). However, he continued to use the term 'spiritual' in his articles.[48]

Philosophy

Although Van Doesburg was influenced by Theosophy, his writings were more in the Hegelian philosophical tradition. Unlike Mondrian, Van Doesburg was better informed of the latest developments in theory and adopted many ideas from other theorists, including Wilhelm Worringer. But although Worringer regarded abstraction as the opposite of naturalism, according to Van Doesburg, art history as a whole developed towards abstraction. Van Doesburg borrowed the idea that art and architecture was composed of separate elements from Wölfflins Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe from 1915. In his lecture Klassiek-Barok-Modern [Classical-Baroque-Modern] (1918), Van Doesburg elaborated on Wölfflin's concept of the contrast between the classical and the baroque, using Hegel's idea of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, where the classical is the thesis, baroque is the antithesis, and modern is the synthesis. [50]

Evolutionary thinking

(De Stijl Vol.5 No.2 1922).

Legend: E = Egyptians, G = Greeks, R = Romans, M = Middle Ages, R = Renaissance, B = Baroque, B = Biedermeier, IR = Idealism and Reform, NG = Neoplasticism (Neue Gestaltung)

Van Doesburg developed the theory of neoplasticism to include an evolutionary and therefore temporal element.[47] From 1919 onwards, through lectures and publications,[51] Van Doesburg worked to demonstrate that art slowly developed as a means of expression from the natural to a means of expression of the spiritual.[52] According to him, the spiritual and the natural in art were not always in balance in the past and neoplasticism would restore this balance. The diagram reproduced here, which Van Doesburg probably drew up as a result of the lectures he gave in Jena, Weimar and Berlin in 1921, clearly indicates the extent to which Van Doesburg thought how nature and spirit were related in the various Western European cultural periods. He begins on the far right with the ancient Egyptians and Greeks, where nature and spirit were still in balance. The ancient Romans focused on the natural, while in the Middle Ages the spiritual predominated. In the Renaissance, art again turned towards the natural, only to be surpassed by the Baroque. The Biedermeier and the Idealism and Reform in the nineteenth century restored the balance somewhat, ending in the time of Neoplasticism (Neue Gestaltung), in which the polarity between the natural and spiritual was completely abolished. However, Van Doesburg did not see his version of neoplasticism as an ideal final stage or as a utopia. As he states in the same lecture: "Never, anywhere is there an ending. The process is unceasing."[53]

Fourth dimension

A number of contributors to De Stijl mention the fourth dimension several times in passing – for example Gino Severini in his article entitled "La Peinture D'Avant-Garde".[54] Passages like these also occur in other avant-garde movements but seldom lead to concrete results.[55] Theo van Doesburg had an interest in the fourth dimension (motion) from 1918, [56][57] eventually finding expression in Elementarism, most prominently seen in his architectural interior designs, such as the Aubette in Strasbourg.[58]

Neoplasticism in painting

Left: visual plane (passive).

Right: color (active).

Neoplasticism assumes that when the painter tries to shape reality (or truth), he never does this from what he sees (object, matter, the physical), but from what originates within himself (subject, idea, the spiritual),[59] or as Georges Vantongerloo puts it: "'La grande vérité, ou la vérité absolu, se rend visible à notre esprit par l'invisible" [The highest truth, or the absolute truth, is imagined through the invisible].[60] Mondrian calls this process 'internalization'.[7] In addition, no painting is created by chance. Each painting is an interplay of space, plane, line and color. These are the plastic (visual) means in painting. If the artist wants to approach the truth as closely as possible, he dissolves the natural form into these most elementary visual means. In this way the painter achieves universal harmony. The role of the artist (the individual or the subjective) is limited to determining the relationship between these visual means (the composition). The artist thus becomes a mediator between the spectator and the absolute (the objective).[61] Following Schoenmaekers – who associated the physical with the horizontal, and the spiritual with the vertical – the neo-plastic painters applied horizontal and vertical lines with rectangular areas of color in order to radically simplify painting, purifying art of those elements that are not directly related to expressing "pure reality".[62]

Neoplasticism in sculpture

According to Van Doesburg, the sculptor is concerned with 'volume ratio'.[63] He applied a similar principle to architecture, concluding that the sculptor is concerned with 'volume ratio' and the architect with 'ratio of enclosed spaces'.[64] In his 1925 book "Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst", Van Doesburg distinguished two elements for sculpture: a positive element (volume) and a negative element (void).

Neoplasticism in architecture

Architecture, unlike painting, has less 'burden' of meaning. Architectural beauty, according to Van Doesburg, is mainly determined by mass ratio, rhythm and tension between the vertical and horizontal (to name just a few visual means in architecture). Many of these ideas come from the German architect Gottfried Semper, for example the great emphasis on walls as a plane and as a divider of space and the principle of 'unity in the multiplicity' (the realisation that buildings, furniture, sculptures and paintings can be seen not only as units, but also as assemblages of separate elements).[65] Semper's ideas were spread in the Netherlands by Berlage, the spiritual father of modern architecture in the Netherlands. It was also Berlage who, after a visit to the United States in 1911, introduced the Netherlands to the work of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright's ideas found favour with the architects of De Stijl, not least because of 'his mystical contrast between the horizontal and vertical, the external and internal, nature and culture'.[66]

The architect J. J. P. Oud talks about the primary means of representation and, like Van Doesburg, sees a strong similarity with modern painting in that respect. According to Oud, the secondary visual means, decoration, do not contribute to a harmonious architecture. Moreover, he is of the opinion that material must be used in a pure manner (reinforced concrete as reinforced concrete, brick as brick, wood as wood) and that the architect should not be guilty of seeking effect.[67] Restrictions were also imposed in architecture, so that a symbolic or decorative application of the visual means was virtually impossible.[68]

Van Doesburg's first definition of architecture comes from his series of articles The new movement in painting from 1916, in which he writes that "for the architect, space is the first conditions for composition" and that the architect "breaks up space through size proportions realized in stone". He added two elements to this starting point in 1925: an active element (mass) and a passive element (space). He then divides the visual media of architecture into positive elements (line, plane, volume, space and time) and negative elements (void and material).[69] By 1923, the inclusion of volume and time as elements of neoplasticism caused serious rifts between Mondrian and Oud, and later with Van Doesburg, who went on the evolve the philosophy of De Stijl to Elementarism.[70][71]

Neoplasticism in film

In 1920, Van Doesburg met the filmmakers Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling. They worked on short, abstract films, based on the relationship of shapes, and the development of shapes over time. After this he made films that consisted of moving compositions with squares and rectangles, which were in line with the principles of neoplasticism. In 1923, Van Doesburg wrote that film should not be seen as a two-dimensional art form, but has its own visual means: light, movement and space.[72]

Neoplasticism in poetry

According to Van Doesburg, poetry, just like painting, was also 'visual'.[73] According to him, poetry is not only about the meaning of the word, but also about the sound. Just as in painting, Van Doesburg strove for a poetry that was not narrative. The New Visual poet used the word directly, without associations with the world around us. This resulted in a series of sound poem and typographical poems. Through typography he created sonority and rhythm, which draws the reader's attention to a particular word. Van Doesburg also published so-called Letter-sound-images under the pseudonym I.K. Bonset; poems that consist only of letters.[74]

Neoplasticism in music

The De Stijl artists also strove for a balanced portrayal of proportion in music. Just as these were determined in painting by size, color and non-color, neo-plastic music is determined by size, tone and non-tone. Mondrian was of the opinion that music, like painting, should be purified of natural influences by, among other things, tightening the rhythm.[75] The non-tone replaces the old rest, but to be 'visual' it must consist of sound; Mondrian suggests using noise for this. Just as in painting, tone and non-tone follow each other directly. This creates a 'flat, pure, sharply defined' music.[76]

Neoplasticism in philosophy

The supporters of the new visual art thought that if neoplasticism was consistently implemented, art would cease to exist. The composer Jacob van Domselaer wrote: "Later there will be no need for art; then all images, all sounds will be superfluous!".[77]

Theo van Doesburg saw neoplasticism as a total vision, which he summarized in an article in De Stijl entitled "Tot een Nieuwe Wereldbeelding" [The new worldview]:

Neoplasticism would not only change the face of the world, but it would also usher in a new way of thinking. With the understanding of the aesthetics of the material, a life-changing experience results in the development of knowledge and wisdom.[78]

List of neoplasticists

Notes

- ^ Mondriaan changed his name to "Mondrian" when he moved to Paris in 1911.

- ^ Subsequently translated most often as "Neoplasticism in painting"

- ^ Historically the term plastic arts pre-dates neoplasticism, denoting the visual arts (painting, sculpture, ceramics), as opposed to the art of writing (literature, music).[15] In academic art, the word plastic means physically shapeable materials.[16] As a graduate of the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten [State academy of fine art], it is reasonable to assume that Mondrian was familiar with this usage. In an essay for De Stijl, he wrote "The freedom to make changes in the plastic position of the means of expression is unique to painting. The sister arts, sculpture and architecture, are less free in this respect".[17] (The modern meaning of the word plastic,a synthetic polymer, was unknown at the time.) Theosophists call the spiritual essence of matter the "plastic soul" (taken from the Sanskrit "Svabhavat"). Mondrian is known to have an interest in theosophy and owned a copy of Blavatsky's book "The Key to Theosophy", which defines the term "plastic" in those terms (page 360).

- ^ By "trialogue", Mondrian means his set of articles for De Stijl.[18][19]

- ^ [plastic, image-forming].[9]

References

- ^ Starasta, Leslie (July 2004). "The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy (3rd edition)". Reference Reviews. 18 (5): 16–17. doi:10.1108/09504120410542931. ISSN 0950-4125. (book review)

- ^ a b Tate (n.d.).

- ^ Madrid Academy of Art (2024).

- ^ Mondrian (1920a).

- ^ Overy (1969), p. 7.

- ^ van Doesburg (1917a).

- ^ a b Mondriaan (1917), pp. 2–6.

- ^ Welsh & Joosten (1969), p. 14.

- ^ a b Holtzman & James (1986), p. 27.

- ^ Threlfall (1978), p. 13.

- ^ Holtzman & James (1986), p. 27.

- ^ Holtzman & James (1986), p. (cover).

- ^ Mondrian (1921).

- ^ a b Holtzman & James (1986), p. 132.

- ^ Kyle (2009), pp. 67, 68.

- ^ Ocvirk et al. (1968), p. 160.

- ^ Holtzman & James (1986), p. 30.

- ^ Mondrian (1995), p. (cover).

- ^ Holtzman & James (1986), p. 82.

- ^ Mondrian (1925).

- ^ Mondrian (2019).

- ^ Martin, Nicholson & Gabo (1937).

- ^ Veen (2017).

- ^ a b c d Overy (1991), p. 42.

- ^ Holtzman & James (1986), p. 14.

- ^ George (2016), p. 82.

- ^ a b van Doesburg (1925), p. 30.

- ^ a b van Doesburg (1968), p. 30.

- ^ van Doesburg (1925), p. 25.

- ^ van Doesburg (1968), p. 25.

- ^ George (2016), p. 75.

- ^ Threlfall (1978), p. 349.

- ^ Martin, Nicholson & Gabo (1937), p. 41.

- ^ Holtzman & James (1986), p. 16.

- ^ Jaffé (1956), pp. 138, 223.

- ^ van Doesburg (1925), pp. 23–26.

- ^ van Doesburg (1968), pp. 23–26.

- ^ van Doesburg (1919a), p. 54.

- ^ van Doesburg (1925), pp. 23–34.

- ^ van Doesburg (1968), pp. 23–34.

- ^ Mondriaan (1917), p. 5.

- ^ Engel (2009), p. 37-39.

- ^ van Doesburg (1920), pp. 45–46.

- ^ van Doesburg (1918a), p. 11.

- ^ Engel (2009), p. 43.

- ^ Nelly van Doesburg (1971) Cited in Jaffé (1983), p. 8

- ^ a b Blotkamp (1982), p. 72.

- ^ a b Overy (1991), p. 36.

- ^ Overy (1991), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Overy (1991), p. 42-43.

- ^ van Doesburg (1922a).

- ^ Overy (1991), p. 43.

- ^ van Doesburg (1922a), pp. 23–32.

- ^ Severini (1918), p. 46.

- ^ Baljeu (1968).

- ^ Blotkamp (1982), p. 30.

- ^ Ubink (1918).

- ^ Baljeu (1974), p. 70.

- ^ van Doesburg (1917b), p. (cover).

- ^ Vantongerloo (1918), p. 100.

- ^ van Doesburg (1918b), p. 47-48.

- ^ Jaffé, Bock & Friedman (1983), p. 111.

- ^ van Doesburg (1920), p. 46.

- ^ Engel (2009), p. 39-40.

- ^ Overy (1991), p. 25.

- ^ Overy (1991), p. 27.

- ^ Oud (1918), pp. 39–41.

- ^ Bock, van Rossem & Somer (2001), p. 80.

- ^ Engel (2009), p. 37.

- ^ Blotkamp (1994), p. 147.

- ^ Baljeu (1974), pp. 166–204.

- ^ Fabre (2009), pp. 47–54.

- ^ Bonset (1922), pp. 88–89.

- ^ Fabre (2009), p. 47.

- ^ Mondrian (1921), p. 114-118.

- ^ Mondrian (1922), p. 17-21.

- ^ Letter from Jacob van Domselaer to Antony Kok (1915) Cited in Jaffé (1983), p. 9

- ^ van Doesburg (1922b), p. 14.

Sources

- Baljeu, Joost (1968). article "Die vierte Dimension" from exhibition catalogue "Theo van Doesburg 1883–1931". Eindhoven.

- Baljeu, Joost (1974). Theo van Doesburg. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780025064409. OCLC 897976.

- Bock, Manfred; van Rossem, Vincent; Somer, Kees (2001). Cornelis van Eesteren, architect, urbanist. Rotterdam, Den Haag: NAi Publishers, EFL Stichting. ISBN 90-7246-962-3.

- Blotkamp, Carel (1982). De Stijl: the formative years. The MIT Press.

- Blotkamp, Carel (1994). Mondrian: The Art of Destruction. Reaktion Books Ltd.

- Bonset, I.K (1922). "Beeldende verskunst en hare verhouding tot de andere kunsten". De Stijl (in Dutch). 5 (6): 88–89.

- Engel, Henk (2009). "Theo van Doesburg & the destruction of architectural theory". In Fabre, Gladys; Hötte, Doris Wintgens (eds.). van Doesburg & the international avant-garde. Constructing a new world. London: Tate Publishing. pp. 36–45. ISBN 978-1-85437-872-9.

- Fabre, Gladys (2009). "A universal language for the arts: interdisciplinarity as a practice, film as a model". In Fabre, Gladys; Hötte, Doris Wintgens (eds.). van Doesburg & the international avant-garde. Constructing a new world. London: Tate Publishing. pp. 46–57. ISBN 978-1-85437-872-9.

- George, Victoria (2016). "Calvin in Mondrian's Colour Theory". In Mark Stocker; Phillip Lindley (eds.). Tributes to Jean Michel Massing. Harvey Miller Publishers. pp. 75–90. ISBN 978-1-909400-38-2.

- Jaffé, H.L.C.; Bock, Manfred; Friedman, Mildred, eds. (1983). De Stijl: 1917-1931. Amsterdam: Meulenhoff/Landshoff. ISBN 90-2908-052-3.

- Holtzman, Harry; James, Martin S. (1986). The New Art - The New Life: the collected writings of Piet Mondrian. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Jaffé, H.L.C. (1956). "De Stijl 1917–1931: The Dutch Contribution to Modern Art". J. M. Meulenhoff.

- Jaffé, H.L.C. (1983). Theo van Doesburg. Amsterdam: Meulenhoff/Landshoff. ISBN 90-290-8272-0.

- Kyle, Jill Anderson (2009). Staviydky; Rothkoff (eds.). Cezanne and American Modernism (First ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300147155.

- Mondriaan, Piet (October 1917). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "De nieuwe beelding in de schilderkunst" [Neoplasticism in Painting]. De Stijl. 1 (1): 2–6.

- Madrid Academy of Art (July 2024). "Plastic Art".

- Martin, J.L.; Nicholson, Ben; Gabo, N., eds. (1937). CIRCLE: International Survey of Constructive Art. Faber and Faber Ltd.

- Mondrian, Piet (1920a), Le Neo-plasticisme: Principe général de l'equivalence plastique [Neo-plasticism: the general principle of plastic equivalence] (in French), Paris: l'Effort Moderne (published January 1921) English translation

- Mondrian, Piet (August 1921). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "The 'Bruiteurs Futuristes Italiens' and 'the new in music'". De Stijl. 4 (8): 114–118.

- Mondrian, Piet (February 1922). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "'Neo-Plasticism (the New Plasticism) and its (its) realization in music (final)'". De Stijl. 5 (2): 17–21.

- Mondrian, Piet (1995) [1920]. Natural reality and abstract reality : an essay in trialogue form. New York: George Braziller. p. (cover). ISBN 9780807613719.

- Mondrian, Piet (1925). [Le néo-plasticisme.] Neue Gestaltung. Neoplastizismus. Nieuwe Beelding [[Le néo-plasticisme.] New design. Neoplasticism. Nieuwe Beelding.]. Bauhausbücher. (no. 5) (in German). Translated by Rudolf F. Hartogh; Max Burchartz. OCLC 503815757.

- Mondrian, Piet (2019). Müller, Lars (ed.). New Design – Neo-Plasticism – Nieuwe Beelding. Bauhausbücher (No. 5). Translated by Holtzman, Harry; James, Martin S. Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers. ISBN 978-3-03778-586-7.

- Oud, J. J. P. (February 1918). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "Architectonische beschouwing bij bijlage VII" [Architectural consideration at Appendix VIII]. De Stijl. 1 (4): 39–41.

- Ocvirk, Otto G.; Bone, Robert O.; Stinson, Robert E; Wigg, Philip R. (1968). Art fundamentals: theory and practice. Dubuque, Iowa: WM C. Brown Company. p. 160.

- Overy, Paul (1991). De Stijl. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20240-0.

- Tate (n.d.). "Neo-plasticism". Art terms. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- Severini, Gino (January 1918). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "La peinture d'avant-garde. IV'". De Stijl (in French). 1 (4).

- Threlfall, Timothy (1978). Piet Mondrian: his life's work and evolution 1872 to 1944 (Thesis). University of Warwick.

- Ubink, J. B. (1918). "De vierde afmeting [The Fourth Dimension]". De Nieuwe Gids. 33: 791–802. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- Vantongerloo, Georges (July 1918). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "Réflexions". De Stijl. 1 (9 (July 1918)).

- Veen, Louis, ed. (2017). Piet Mondrian – The Complete Writings: Essays and notes in original versions. Primavera Pers, Leiden.

- van Doesburg, Theo, ed. (October 1917). "Ter inleiding" [By way of introduction]. De Stijl (in Dutch). 1 (1).

- van Doesburg, Theo (1917). De Nieuwe Beweging in de Schilderkunst [The New Movement in Painting]. Delft: J. Waltman – via Digital Dada Library.

- van Doesburg, Theo (February 1918). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "Fragments. I'". De Stijl. 1 (4).

- van Doesburg, Theo, ed. (November 1918). "Aanteekeningen over monumentale kunst" [Notes on monumental art]. De Stijl (in Dutch). 2 (1): 10–12.

- van Doesburg, Theo (1919a). Drie voordrachten over de nieuwe beeldende kunst [Three lectures on the new visual arts] (in Dutch). Amsterdam: A.C. Berlage.

- van Doesburg, Theo, ed. (March 1920). "Aanteekeningen bij de Bijlagen VI en VII" [Notes to Annexes VI and VII]. De Stijl (in Dutch). 3 (5): 44–46.

- van Doesburg, Theo, ed. (February 1922). "Der Wille zum Stil (Neugestaltung von Leben, Kunst und Technik)" [The will to style (redesigning life, art and technology)]. De Stijl (in German). 5 (2): 23–32.

- van Doesburg, Theo, ed. (March 1922). "Von den neuen Ästhetik zur materiellen Verwirklichung" [From the new aesthetics to material realization]. De Stijl (in German). 6 (1): 10–14.

- van Doesburg, Theo (1925). Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst [Principles of Neo-Plastic Art]. München: Albert Langen Verlag.

- van Doesburg, Theo (1968). Principles of Neo-Plastic Art. London: Lund Humphries.

- Welsh, Robert P.; Joosten, J.M., eds. (1969). Two Mondrian Sketchbooks 1912–1914.

Further reading

- Bax, Marty (2001). Complete Mondrian. Aldershot: Lund Humphries. ISBN 0-85331-803-4. OCLC 49525534.

- van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "De Stijl (1917-1921) | 8 volumes, 90 numbers". International Dada Archive.

- Frampton, Kenneth (1982). "Neoplasticism and Architecture: Formation and Transformation". In Jaffé, H.L.C.; Bock, Manfred; Friedman, Mildred (eds.). De Stijl: 1917–1931. Amsterdam: Meulenhoff/Landshoff. ISBN 90-2908-052-3.

- Huszàr, Vilmos (March 1918). van Doesburg, Theo (ed.). "Aesthetische beschouwingen III (bij bijlagen 9 en 10)" [Aesthetic considerations III (appendices 9 and 10)]. De Stijl. 1 (5): 54–57.

- Mondrian, Piet (1920). Le Néoplasticisme: Principe Général de l'Equivalence Plastique [Neo-Plasticism: General Principle of Plastic Equivalence] (in French). l'Effort Moderne.

- Mondrian, Piet (1920). Neo-Plasticism: General Principle of Plastic Equivalence [Le Néoplasticisme: Principe Général de l'Equivalence Plastique]. l'Effort Moderne.

- Schoenmaekers, Mathieu H. J. (1915). Het Nieuwe Wereldbeeld [The New Worldview] (in Dutch). Van Dishoeck.

- Schoenmaekers, Mathieu H. J. (1915). The New Worldview [Het Nieuwe Wereldbeeld]. Van Dishoeck.

- Schoenmaekers, Mathieu H. J. (1916). Beginselen Der Beeldende Wiskunde [Principles of Visual Mathematics] (in Dutch). Van Dishoeck.

- Schoenmaekers, Mathieu H. J. (1916). Principles of Visual Mathematics [Beginselen Der Beeldende Wiskunde]. Van Dishoeck.

- van Doesburg, Theo (1919). Drie voordrachten over de nieuwe beeldende kunst verscheen [Three Presentations On The New Visual Arts] (in Dutch). Amsterdam.

- van Doesburg, Theo (1919). Three Presentations On The New Visual Arts [Drie voordrachten over de nieuwe beeldende kunst verscheen]. Amsterdam: Uitgegeven door de maatschappij voor gooede en goedekoope.

- van Doesburg, Theo (1916). The New Movement in Painting [De nieuwe beweging in de schilderkunst]. De Beweging (Vol. 12, No. 9, pp. 226–235). (in English and Dutch)

- van Doesburg, Theo (1919). "Fundamental Concepts of the New Visual Art" [Grondbegrippen Der Nieuwe Beeldende Kunst]. Tijdschrift voor Wijsbegeerte. 13: 30–49, 169–188. (in English and Dutch)