Narmer Macehead

The Narmer macehead is an ancient Egyptian decorative stone mace head.[1] It was found in the "main deposit" in the temple area of the ancient Egyptian city of Nekhen (Hierakonpolis) by James Quibell in 1898.[2] It is dated to the Early Dynastic Period reign of king Narmer (c. 31st century BC) whose serekh is engraved on it. The macehead is now kept at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Motifs

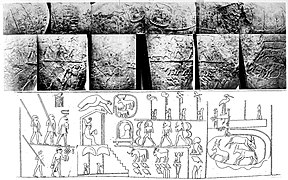

The Narmer macehead is better preserved than the Scorpion Macehead and has had various interpretations. One opinion is that, as for the Palette, the events depicted on it record the year it was manufactured and presented to the temple, a custom which is known from other finds at Hierakonpolis.[3] A theory held by earlier scholars, including Petrie and Walter Emery, is that the macehead commemorates great occasions like Narmer's Heb Sed festival or marriage to a possible Queen Neithhotep.[4]

On the left side of this macehead is a king sitting under a canopy on a dais; he is wearing the Red Crown (deshret) and is covered in a long cloth or cloak. The king is holding a flail and above the canopy a vulture, possibly the local goddess Nekhbet, hovers with spread wings. Nekhen, or Hierakonpolis, was one of four power centers in Upper Egypt that preceded the consolidation of Upper Egypt at the end of the Naqada III period.[6] Hierakonpolis’s religious importance continued long after its political role had declined.[7] Directly in front of the king is another dais, or possibly litter, on which a cloaked figure sits facing him. This figure has been interpreted as a princess being presented to the king for marriage, the king's child or a deity.[3] The dais is covered by a bow-like structure and behind it are three registers. In the center register, attendants are walking or running behind the dais. In the top register, an enclosure, with what seems like a cow and a calf, might symbolise the nome of Theb-ka, or the goddess Hathor and her son Horus, deities associated with kingship since earliest times. Behind the enclosure, four standard-bearers approach the throne. In the bottom register, in front of the fan-bearers, are a collection of offerings.[citation needed]

On the center part of the macehead, behind the throne with the seated king, there is a figure just like the supposed sandal-bearer from the Narmer palette, likewise with the rosette sign above its head. He is followed by a man carrying a long pole. Above him three men are walking, two of them also carrying long poles. The serekh displaying the signs for Narmer can be seen above these men.

The top field to the right of the center field shows a building, perhaps a shrine, with a heron perched on its roof. Below this, an enclosure shows three animals, probably antelopes. This has been suggested as signifying the ancient town of Buto, the place where the events described on the macehead might have taken place.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Narmer Catalog (Narmer Macehead)

- ^ Quibell, pp. 8–9, pl. 26B.

- ^ a b Millet 1990.

- ^ Walter B Emery, Archaic Egypt, Pelican Books,1961, ISBN 0-14-020462-8

- ^ Wengrow, David (2006). The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, C.10,000 to 2,650 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–44. ISBN 9780521835862.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 36–41.

- ^ Friedman 2001, pp. 98–100, volume 2.

Bibliography

- Friedman, Renée (2001), "Hierakonpolis", in Redford, Donald B. (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 98–100, volume 2.

- Millet, N. B. (1990). "The Narmer macehead and related objects". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 27: 53–59. doi:10.2307/40000073. JSTOR 40000073..

- Quibell, J. E. (1900), Hierakonpolis, Part I, British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account, vol. 4, London: Bernard Quaritch.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London and New York: Routledge.

- Yurco, F. J. (1995). "Narmer: First king of Upper and Lower Egypt. A Reconsideration of his palette and macehead". Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities. 25..

- "Narmer Macehead Bibliography (Narmer Catalog)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-27. Retrieved 2017-09-26.