NATO Commander

| NATO Commander | |

|---|---|

Cover art by David Martin | |

| Developer(s) | MicroProse |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Designer(s) | Sid Meier |

| Programmer(s) | Atari Sid Meier Apple Jim Synoski Commodore Al Duffy[2] |

| Platform(s) | Atari 8-bit, Apple II,[3] Commodore 64[1] |

| Release | 1983: Atari[1] 1984: Apple, C64 |

| Genre(s) | Real-time strategy[4] |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

NATO Commander is a strategy video game designed by Sid Meier for Atari 8-bit computers and published in 1983 by MicroProse. Ports to the Apple II, and Commodore 64 were released the following year.

The player takes the role of the Supreme Allied Commander of NATO forces in Europe as they respond to a massive Warsaw Pact attack. The goal is to slow their advance and inflict casualties, hoping to force a diplomatic end to the war before West Germany is overrun.

The same game engine was also used as the basis for Conflict in Vietnam, Crusade in Europe and Decision in the Desert.[citation needed]

Gameplay

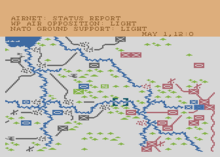

The scenario involves a Cold War Soviet invasion of West Germany. The player is given operational control of NATO land armies, while the computer controls the Soviets, and must repel the invasion by deploying his forces geographically and choosing their offensive or defensive roles.[3] As the battle progresses, both operational and political factors influence the outcome. NATO may lose or win back cities and territory; according to the scenario chosen the player had the option to decide to stave off the Warsaw Pact onslaught by countercharging head-on, buying time for space awaiting a diplomatic solution, or mounting a counteroffensive.[citation needed]

The game's interface has strong similarities to the seminal Eastern Front in the way the map is displayed and various orders are given to the units, but NATO Commander takes place in real-time, with one second of time representing 5 minutes passing in the game. It also has various unit types including armor, infantry, armored infantry (mostly for reconnaissance), airborne troops, air force and helicopters. The latter are useful for attacking Soviet units that are isolated or surrounded, which protects them from surface-to-air missiles from the Soviet side of the map. Another major change is the hidden movement system, which only displays Soviet units that are visible to the allied units. Air forces can be used for air superiority, ground attack or as a reconnaissance force to help reveal the hidden Soviet forces.[citation needed]

The game has a variety of scenarios, each one larger than the last. The first is simply a limited encounter on the front, while the next include a counterattack around the Hannover-Hamburg axis, awaiting the French Army's mobilization or the Italian Army's decision to enter the fray or not.[3] Tactical nuclear weapons and chemical weapons are available to both sides but their use often carried heavy image penalties and could initiate an escalation.[3] In the end, either the player or the Soviets surrender, based on how much land and combat-ready forces remain.[3]

Reception

Computer Gaming World in 1984 criticized NATO Commander for being imbalanced in favor of the Warsaw Pact, but concluded that the game was one of the first combat games to take advantage of computer power, resulting in a "superb strategic simulation".[5] A 1992 survey in the magazine of wargames with modern settings gave the game three stars out of five,[6] and a 1994 survey gave it two-plus stars.[7]

References

- ^ a b NATO Commander at GameFAQs

- ^ "Full text of MicroProse Catalog". archive.org. 1986.

- ^ a b c d e NATO Commander at MobyGames

- ^ "NATO Commander". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- ^ Bausman, Mark (February 1984). "NATO Commander: Review". Computer Gaming World. Vol. 4, no. 1. pp. 26, 45. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (June 1992). "The Modern Games: 1950 - 2000". Computer Gaming World. p. 120. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (January 1994). "War In Our Time / A Survey Of Wargames From 1950-2000". Computer Gaming World. pp. 194–212.

External links

- NATO Commander at MobyGames

- NATO Commander at Atari Mania

- NATO Commander at Lemon 64

- NATO Commander can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive