Chữ Nôm

| Chữ Nôm 𡨸喃 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 13th century[1][2] – 20th century |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom, columns from right to left (traditional) Left-to-right (modern) |

| Languages | Vietnamese |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Nom Tay[3] |

Sister systems | Sawndip[4] |

Chữ Nôm (𡨸喃, IPA: [t͡ɕɨ˦ˀ˥ nom˧˧])[5] is a logographic writing system formerly used to write the Vietnamese language. It uses Chinese characters to represent Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and some native Vietnamese words, with other words represented by new characters created using a variety of methods, including phono-semantic compounds.[6] This composite script was therefore highly complex and was accessible to less than five percent of the Vietnamese population who had mastered written Chinese.[7]

Although all formal writing in Vietnam was done in classical Chinese until the early 20th century (except for two brief interludes),[8] chữ Nôm was widely used between the 15th and 19th centuries by the Vietnamese cultured elite for popular works in the vernacular, many in verse. One of the best-known pieces of Vietnamese literature, The Tale of Kiều, was written in chữ Nôm by Nguyễn Du.

The Vietnamese alphabet created by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries, with the earliest known usage occurring in the 17th century, replaced chữ Nôm as the preferred way to record Vietnamese literature from the 1920s. While Chinese characters are still used for decorative, historic and ceremonial value, chữ Nôm has fallen out of mainstream use in modern Vietnam. In the 21st century, chữ Nôm is being used in Vietnam for historical and liturgical purposes. The Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies at Hanoi is the main research centre for pre-modern texts from Vietnam, both Chinese-language texts written in Chinese characters (chữ Hán) and Vietnamese-language texts in chữ Nôm.

Etymology

The Vietnamese word chữ 'character' is derived from the Middle Chinese word dziH 字, meaning '[Chinese] character'.[9][10] The word Nôm 'Southern' is derived from the Middle Chinese word nom 南,[a] meaning 'south'.[11][12] It could also be based on the dialectal pronunciation from the South Central dialects (most notably in the name of province of Quảng Nam, known locally as Quảng Nôm).[13]

There are many ways to write the name chữ Nôm in chữ Nôm characters. The word chữ may be written as 字, 𫳘(⿰字宁), 𡨸, 𫿰(⿰字文), 𡦂(⿰字字), 𲂯(⿰貝字), 𱚂(⿱字渚), or 宁, while Nôm is written as 喃.[14][15]

Terminology

Chữ Nôm is the logographic writing system of the Vietnamese language. It is based on the Chinese writing system but adds a large number of new characters to make it fit the Vietnamese language. Common historical terms for chữ Nôm were Quốc Âm (國音, 'national sound') and Quốc ngữ (國語, 'national language').

In Vietnamese, Chinese characters are called chữ Hán (𡨸漢 'Han characters'), chữ Nho (𡨸儒 'Confucian characters', due to the connection with Confucianism) and uncommonly as Hán tự (漢字 'Han characters').[16][17][18] Hán văn (漢文) refers literature written in Literary Chinese.[19][20]

The term Hán Nôm (漢喃 'Han and chữ Nôm characters')[21] in Vietnamese designates the whole body of premodern written materials from Vietnam, either written in Chinese (chữ Hán) or in Vietnamese (chữ Nôm).[22] Hán and Nôm could also be found in the same document side by side,[23] for example, in the case of translations of books on Chinese medicine.[24] The Buddhist history Cổ Châu Pháp Vân phật bản hạnh ngữ lục (1752) gives the story of early Buddhism in Vietnam both in Hán script and in a parallel Nôm translation.[25] The Jesuit Girolamo Maiorica (1605–1656) had also used parallel Hán and Nôm texts.

The term chữ Quốc ngữ (𡨸國語 'national language script') refers to the Vietnamese alphabet in current use, but was used to refer to chữ Nôm before the Vietnamese alphabet was widely used.

History

Chinese characters were introduced to Vietnam after the Han dynasty conquered Nanyue in 111 BC. Independence was achieved after the Battle of Bạch Đằng in 938, but Literary Chinese was adopted for official purposes in 1010.[26] For most of the period up to the early 20th century, formal writing was indistinguishable from contemporaneous classical Chinese works produced in China, Korea, and Japan.[27]

Vietnamese scholars were thus intimately familiar with Chinese writing. In order to record their native language, they applied the structural principles of Chinese characters to develop chữ Nôm. The new script was mostly used to record folk songs and for other popular literature.[28] Vietnamese written in chữ Nôm briefly replaced Chinese for official purposes under the Hồ dynasty (1400–1407) and under the Tây Sơn (1778–1802), but in both cases this was swiftly reversed.[8]

Early development

The use of Chinese characters to transcribe the Vietnamese language can be traced to an inscription with the two characters "布蓋", as part of the posthumous title of Phùng Hưng, a national hero who succeeded in briefly expelling the Chinese in the late 8th century. The two characters have literal Chinese meanings 'cloth' and 'cover', which make no sense in this context. They have thus been interpreted as a phonetic transcription, via their Middle Chinese pronunciations buH kajH, of a Vietnamese phrase, either vua cái 'great king', or bố cái 'father and mother' (of the people).[29][30]

After Vietnam established its independence from China in the 10th century, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh (r. 968–979), the founder of the Đinh dynasty, named the country Đại Cồ Việt 大瞿越. The first and third Chinese characters mean 'great' and 'Viet'. The second character was often used to transcribe non-Chinese terms and names phonetically. In this context, cồ is an obsolete Vietnamese word for 'big'.[b][31][32]

The oldest surviving Nom inscription, dating from 1210, is a list naming 21 people and villages on a stele at the Tự Già Báo Ân pagoda in Tháp Miếu village (Mê Linh District, Hanoi).[33][34][35] Another stele at Hộ Thành Sơn in Ninh Bình Province (1343) lists 20 villages.[36][37][c]

Trần Nhân Tông (r. 1278–1293) ordered that Nôm be used to communicate his proclamations to the people.[36][39] The first literary writing in Vietnamese is said to have been an incantation in verse composed in 1282 by the Minister of Justice Nguyễn Thuyên and thrown into the Red River to expel a menacing crocodile.[36] Four poems written in Nom from the Tran dynasty, two by Trần Nhân Tông and one each by Huyền Quang and Mạc Đĩnh Chi, were collected and published in 1805.[40]

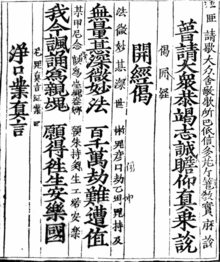

The Nôm text Phật thuyết Đại báo phụ mẫu ân trọng kinh ('Sūtra explained by the Buddha on the Great Repayment of the Heavy Debt to Parents') was printed around 1730, but conspicuously avoids the character 利 lợi, suggesting that it was written (or copied) during the reign of Lê Lợi (1428–1433). Based on archaic features of the text compared with the Tran dynasty poems, including an exceptional number of words with initial consonant clusters written with pairs of characters, some scholars suggest that it is a copy of an earlier original, perhaps as early as the 12th century.[42]

Hồ dynasty (1400–07) and Ming conquest (1407–27)

During the seven years of the Hồ dynasty (1400–07) Classical Chinese was discouraged in favor of vernacular Vietnamese written in Nôm, which became the official script. The emperor Hồ Quý Ly even ordered the translation of the Book of Documents into Nôm and pushed for reinterpretation of Confucian thoughts in his book Minh đạo.[39] These efforts were reversed with the fall of the Hồ and Chinese conquest of 1407, lasting twenty years, during which use of the vernacular language and demotic script were suppressed.[43]

During the Ming dynasty occupation of Vietnam, chữ Nôm printing blocks, texts and inscriptions were thoroughly destroyed; as a result the earliest surviving texts of chữ Nôm post-date the occupation.[44]

15th to 19th century

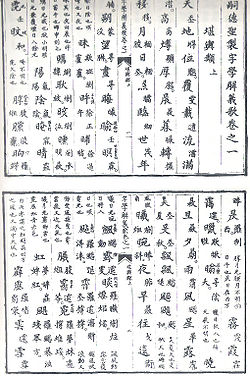

Among the earlier works in Nôm of this era are the writings of Nguyễn Trãi (1380–1442).[45] The corpus of Nôm writings grew over time as did more scholarly compilations of the script itself. Trịnh Thị Ngọc Trúc, consort of King Lê Thần Tông, is generally given credit for Chỉ nam ngọc âm giải nghĩa (指南玉音解義; 'guide to Southern Jade sounds: explanations and meanings'), a 24,000-character bilingual Hán-to-Nôm dictionary compiled between the 15th and 18th centuries, most likely in 1641 or 1761.[46][47]

While almost all official writings and documents continued to be written in classical Chinese until the early 20th century, Nôm was the preferred script for literary compositions of the cultural elites. Nôm reached its golden period with the Nguyễn dynasty in the 19th century as it became a vehicle for diverse genres, from novels to theatrical pieces, and instructional manuals. Although it was prohibited during the reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1840),[48] apogees of Vietnamese literature emerged with Nguyễn Du's The Tale of Kiều[49] and Hồ Xuân Hương's poetry. Although literacy in premodern Vietnam was limited to just 3 to 5 percent of the population,[50] nearly every village had someone who could read Nôm aloud for the benefit of other villagers.[51] Thus these Nôm works circulated orally in the villages, making it accessible even to the illiterates.[52]

Chữ Nôm was the dominant script in Vietnamese Catholic literature until the late 19th century.[53] In 1838, Jean-Louis Taberd compiled a Nôm dictionary, helping with the standardization of the script.[54]

The reformist Catholic scholar Nguyễn Trường Tộ presented the Emperor Tự Đức with a series of unsuccessful petitions (written in classical Chinese, like all court documents) proposing reforms in several areas of government and society. His petition Tế cấp bát điều (濟急八條 'Eight urgent matters', 1867), includes proposals on education, including a section entitled Xin khoan dung quốc âm ('Please tolerate the national voice'). He proposed to replace classical Chinese with Vietnamese written using a script based on Chinese characters that he called Quốc âm Hán tự (國音漢字 'Han characters with national pronunciations'), though he described this as a new creation, and did not mention chữ Nôm.[55][56][57]

French Indochina and the Latin alphabet

From the latter half of the 19th century onwards, the French colonial authorities discouraged or simply banned the use of classical Chinese, and promoted the use of the Vietnamese alphabet, which they viewed as a stepping stone toward learning French. Language reform movements in other Asian nations stimulated Vietnamese interest in the subject. Following the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, Japan was increasingly cited as a model for modernization. The Confucian education system was compared unfavourably to the Japanese system of public education. According to a polemic by writer Phan Châu Trinh, "so-called Confucian scholars" lacked knowledge of the modern world, as well as real understanding of Han literature. Their degrees showed only that they had learned how to write characters, he claimed.[58]

The popularity of Hanoi's short-lived Tonkin Free School suggested that broad reform was possible. In 1910, the colonial school system adopted a "Franco-Vietnamese curriculum", which emphasized French and alphabetic Vietnamese. The teaching of Chinese characters was discontinued in 1917.[59] On December 28, 1918, Emperor Khải Định declared that the traditional writing system no longer had official status.[59] The traditional Civil Service Examination, which emphasized the command of classical Chinese, was dismantled in 1915 in Tonkin and was given for the last time at the imperial capital of Huế on January 4, 1919.[59] The examination system, and the education system based on it, had been in effect for almost 900 years.[59]

The decline of the Chinese script also led to the decline of chữ Nôm given that Nôm and Chinese characters are so intimately connected.[60] After the First World War, chữ Nôm gradually died out as the Vietnamese alphabet grew more and popular.[61] In an article published in 1935 (based on a lecture given in 1925), Georges Cordier estimated that 70% of literate persons knew the alphabet, 20% knew chữ Nôm and 10% knew Chinese characters.[62] However, estimates of the rate of literacy in the late 1930s range from 5% to 20%.[63] By 1953, literacy (using the alphabet) had risen to 70%.[64]

The Gin people, descendants of 16th-century migrants from Vietnam to islands off Dongxing in southern China, now speak a form of Yue Chinese and Vietnamese, but their priests use songbooks and scriptures written in chữ Nôm in their ceremonies.[65]

Texts

- Đại Việt sử ký tiệp lục tổng tự.[66] This history of Vietnam was written during the Tây Sơn dynasty. The original is Hán, and there is also a Nôm translation.

- Nguyễn Du, The Tale of Kieu (1820) The poem is full of obscure archaic words and Chinese borrowings, so that modern Vietnamese struggle to understand an alphabetic transcription without clarifications.

- Nguyễn Trãi, Quốc âm thi tập ("National Language Poetry Compilation")

- Phạm Đình Hồ, Nhật Dụng Thường Đàm (1851). A Hán-to-Nôm dictionary for Vietnamese speakers.

- Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, Lục Vân Tiên (19th century)

- Đặng Trần Côn, Chinh Phụ Ngâm Khúc (18th century)

- Various poems by Hồ Xuân Hương (18th century)

- Mechanics and Crafts of the People of Annam – French manuscript with illustrations depicting Vietnamese culture in French Indochina, the illustrations are described in chữ Nôm.

- Ngô Thì Nhậm, Tam thiên tự – Used to teach beginners Chinese characters and chữ Nôm.

- Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Nhậm, Tự Đức thánh chế tự học giải nghĩa ca – a 32,004 character bilingual Literary Chinese – Vietnamese character dictionary.

Types of texts

- Giải âm (解音) - a category of chữ Nôm texts that translates the "sounds" (word-for-word) of the original Literary Chinese text.[67][68] Examples include Tam thiên tự giải âm (三千字解音), etc. Often these translations attempt to match the word order as the original Literary Chinese text with no regard for Vietnamese syntax). There is significant diversity within works called giải âm (even within a single text), with some coming fairly close to the modern concept of translation, while some are closer to annotations with "word-matching" between Literary Chinese and Vietnamese, with little to no regard to the structure or syntax of Vietnamese.

Here is a line in Tam tự kinh lục bát diễn âm (三字經六八演音), a Vietnamese translation of the Three Character Classic. It features the original text on the top of the page and the Vietnamese translation on the bottom.

人不𭓇不知理 (Nhân bất học bất tri lý)

𠊚空𭓇別𨤰夷麻推 (Người không học biết nhẽ gì mà suy)

Without learning, one does not understand reason.[d]

- Diễn âm (演音) - synonym of giải âm (解音).

- Giải nghĩa (解義) - a category of chữ Nôm texts that translates the "meaning", often having no regard for Literary Chinese syntax.[69] Examples include Chỉ nam ngọc âm giải nghĩa (指南玉音解義).[69] Some giải nghĩa or diễn nghĩa works focus on extracting as much meaning as possible from the source texts, with little to no regard to the structure and syntax of Literary Chinese.

- Diễn nghĩa (演義) - synonym of giải nghĩa (解義).

Characters

Vietnamese is a tonal language, like Chinese, and has nearly 5,000 distinct syllables.[26] In chữ Nôm, each monosyllabic word of Vietnamese was represented by a character, either borrowed from Chinese or locally created. The resulting system was even more difficult to use than the Chinese script.[28]

As an analytic language, Vietnamese was a better fit for a character-based script than Japanese and Korean, with their agglutinative morphology.[51] Partly for this reason, there was no development of a phonetic system that could be taught to the general public, like Japanese kana syllabary or the Korean hangul alphabet.[70] Moreover, most Vietnamese literati viewed Chinese as the proper medium of civilized writing, and had no interest in turning Nôm into a form of writing suitable for mass communication.[51]

Variant characters

Chữ Nôm has never been standardized.[71] As a result, a Vietnamese word could be represented by several Nôm characters. For example, the very word chữ ('character', 'script'), a Chinese loanword, can be written as either 字 (Chinese character), 𡦂 (Vietnamese-only compound-semantic character) or 𡨸 (Vietnamese-only semantic-phonetic character). For another example, the word giữa ('middle'; 'in between') can be written either as 𡨌 (⿰守中) or 𫡉 (⿰字中). Both characters were invented for Vietnamese and have a semantic-phonetic structure, the difference being the phonetic indicator (守 vs. 字).

Another example of a Vietnamese word that is represented by several Nôm characters is the word for moon, trăng. It can be represented by a Chinese character that is phonetically similar to trăng, 菱 (lăng), a chữ Nôm character, 𢁋 (⿱巴陵) which is composed of two phonetic components 巴 (ba) and 陵 (lăng) for the Middle Vietnamese blăng, or a chữ Nôm character, 𦝄 (⿰月夌) composed of a phonetic component 夌 (lăng) and a semantic component meaning 月 ('moon').

Borrowed characters

Unmodified Chinese characters were used in chữ Nôm in three different ways.

- A large proportion of Vietnamese vocabulary had been borrowed from Chinese during the Tang period. Such Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary could be written with the original Chinese character for each word, for example:[72]

- One way to represent a native Vietnamese word was to use a Chinese character for a Chinese word with a similar meaning. For example, 本 may also represent vốn ('capital, funds'). In this case, the word vốn is actually an earlier Chinese loan that has become accepted as Vietnamese; William Hannas claims that all such readings are similar early loans.[72]

- Alternatively, a native Vietnamese word could be written using a Chinese character for a Chinese word with a similar sound, regardless of the meaning of the Chinese word. For example, 沒 (Early Middle Chinese /mət/[76]) may represent the Vietnamese word một ('one').[77]

The first two categories are similar to the on and kun readings of Japanese kanji respectively.[77] The third is similar to ateji, in which characters are used only for their sound value, or the Man'yōgana script that became the origin of hiragana and katakana.

When a character would have two readings, a diacritic may be added to the character to indicate the "indigenous" reading. The two most common alternate reading diacritical marks are cá (𖿰), (a variant form of 个) and nháy (𖿱).[78] Thus when 本 is meant to be read as vốn, it is written as 本𖿱,[e] with a diacritic at the upper right corner.[79]

Other alternate reading diacritical marks include tháu đấm (草𢶸) where a character is represented by a simplified variant with two points on either side of the character.[80]

Locally invented characters

In contrast to the few hundred Japanese kokuji (国字) and handful of Korean gukja (국자, 國字), which are mostly rarely used characters for indigenous natural phenomena, Vietnamese scribes created thousands of new characters, used throughout the language.[81]

As in the Chinese writing system, the most common kind of invented character in Nôm is the phono-semantic compound, made by combining two characters or components, one suggesting the word's meaning and the other its approximate sound. For example,[79]

- 𠀧 (ba 'three') is composed of the phonetic part 巴 (Sino-Vietnamese reading: ba) and the semantic part 三 'three'. 'Father' is also ba, but written as 爸 (⿱父巴), while 'turtle' is con ba ba 𡥵蚆蚆.

- 媄 (mẹ 'mother') has 女 'woman' as semantic component and 美 (Sino-Vietnamese reading: mỹ) as phonetic component.[f]

A smaller group consists of semantic compound characters, which are composed of two Chinese characters representing words of similar meaning. For example, 𡗶 (giời or trời 'sky', 'heaven') is composed of 天 ('sky') and 上 ('upper').[79][82]

A few characters were obtained by modifying Chinese characters related either semantically or phonetically to the word to be represented. For example,

- the Nôm character 𧘇 (ấy 'that', 'those') is a simplified form of the Chinese character 衣 (Sino-Vietnamese reading: ý).[83]

- the Nôm character 𫜵 (làm 'work', 'labour') is a simplified form of the Chinese character 濫 (Sino-Vietnamese reading: lạm) (濫 > 𪵯 > 𫜵).[84]

- the Nôm character 𠬠 (một 'one') comes from the right part of the Chinese character 没 (Sino-Vietnamese reading: một).[85]

Example

As an example of the way chữ Nôm was used to record Vietnamese, the first two lines of the Tale of Kiều (1871 edition), written in the traditional six-eight form of Vietnamese verse, consist of 14 characters:[86]

𤾓

Trăm

hundred

𢆥

năm

year

𥪞

trong

in

𡎝

cõi

world

𠊛

người

person

些

ta,

our

A hundred years—in this life span on earth,

𡨸

Chữ

word

才

tài

talent

𡨸

chữ

word

命

mệnh

destiny

窖

khéo

clever

𱺵

là

to be

恄

ghét

hate

饒

nhau.

each other

talent and destiny are apt to feud.[87]

| character | word | gloss | derivation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 𤾓 (⿱百林) | trăm | hundred | compound of 百 'hundred' and 林 lâm |

| 𢆥 (⿰南年) | năm | year | compound of 南 nam and 年 'year' |

| 𥪞 (⿺竜內) | trong | in | compound of 竜 long and 內 'inside' |

| 𡎝 (⿰土癸) | cõi | world | compound of 土 'earth' and 癸 quý |

| 𠊛 (⿰㝵人) | người | person | compound of 㝵 ngại and 人 'person' |

| 些 | ta | our | character of homophone Sino-Vietnamese ta 'little, few; rather, somewhat' |

| 𡨸 (⿰宁字) | chữ | word | compound of 宁 trữ and 字 'character; word' |

| 才 | tài | talent | Sino-Vietnamese word |

| 𡨸 (⿰宁字) | chữ | word | compound of 宁 trữ and 字 'character; word' |

| 命 | mệnh | destiny | Sino-Vietnamese word |

| 窖 | khéo | clever | variant character of the near-homophone Sino-Vietnamese 竅 khiếu 'hole', Sino-Vietnamese reading of 窖 is giáo |

| 𱺵 (⿱罒𪜀) | là | to be | simplified form of 羅 là 'to be', using the character of near-homophone Sino-Vietnamese la 'net for catching birds' |

| 恄 | ghét | hate | compound of 忄 'heart' classifier and 吉 cát |

| 饒 | nhau | each other | character of near-homophone Sino-Vietnamese nhiêu 'bountiful, abundant, plentiful' |

Computer encoding

In 1993, the Vietnamese government released an 8-bit coding standard for alphabetic Vietnamese (TCVN 5712:1993, or VSCII), as well as a 16-bit standard for Nôm (TCVN 5773:1993).[88] This group of glyphs is referred to as "V0." In 1994, the Ideographic Rapporteur Group agreed to include Nôm characters as part of Unicode.[89] A revised standard, TCVN 6909:2001, defines 9,299 glyphs.[90] About half of these glyphs are specific to Vietnam.[90] Nôm characters not already encoded were added to CJK Unified Ideographs Extension B.[90] (These characters have five-digit hexadecimal code points. The characters that were encoded earlier have four-digit hex.)

| Code | Characters | Unicode block | Standard | Date | V Source | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V0 | 2,246 | Basic Block (593), A (138), B (1,515) | TCVN 5773:1993 | 2001 | V0-3021 to V0-4927 | 5 |

| V1 | 3,311 | Basic Block (3,110), C (1) | TCVN 6056:1995 | 1999 | V1-4A21 to V1-6D35 | 2, 5 |

| V2 | 3,205 | Basic Block (763), A (151), B (2,291) | VHN 01:1998 | 2001 | V2-6E21 to V2-9171 | 2, 5 |

| V3 | 535 | Basic Block (91), A (19), B (425) | VHN 02:1998 | 2001 | V3-3021 to V3-3644 | Manuscripts |

| V4 | 785 (encoded) | Extension C | Defined as sources 1, 3, and 6 | 2009 | V4-4021 to V4-4B2F | 1, 3, 6 |

| V04 | 1,028 | Extension E | Unencoded V4 and V6 characters | Projected | V04-4022 to V04-583E | V4: 1, 3, 6; V6: 4, manuscripts |

| V5 | ~900 | Proposed in 2001, but already coded | 2001 | None | 2, 5 | |

| Sources: Nguyễn Quang Hồng,[90] "Unibook Character Browser", Unicode, Inc., "Code Charts – CJK Ext. E" (N4358-A).[91] | ||||||

Characters were extracted from the following sources:

- Hoàng Triều Ân, Tự điển chữ Nôm Tày [Nôm of the Tay People], 2003.

- Institute of Linguistics, Bảng tra chữ Nôm [Nôm Index], Hanoi, 1976.

- Nguyễn Quang Hồng, editor, Tự điển chữ Nôm [Nôm Dictionary], 2006.

- Father Trần Văn Kiệm, Giúp đọc Nôm và Hán Việt [Help with Nôm and Sino-Vietnamese], 2004.

- Vũ Văn Kính & Nguyễn Quang Xỷ, Tự điển chữ Nôm [Nôm Dictionary], Saigon, 1971.

- Vũ Văn Kính, Bảng tra chữ Nôm miền Nam [Table of Nôm in the South], 1994.

- Vũ Văn Kính, Bảng tra chữ Nôm sau thế kỷ XVII [Table of Nôm After the 17th Century], 1994.

- Vũ Văn Kính, Đại tự điển chữ Nôm [Great Nôm Dictionary], 1999.

- Nguyễn Văn Huyên, Góp phần nghiên cứu văn hoá Việt Nam [Contributions to the Study of Vietnamese Culture], 1995.[90]

The V2, V3, and V4 proposals were developed by a group at the Han-Nom Research Institute led by Nguyễn Quang Hồng.[90] V4, developed in 2001, includes over 400 ideograms formerly used by the Tày people of northern Vietnam.[90] This allows the Tày language to get its own registration code.[90] V5 is a set of about 900 characters proposed in 2001.[90] As these characters were already part of Unicode, the IRG concluded that they could not be edited and no Vietnamese code was added.[90] (This is despite the fact that national codes were added retroactively for version 3.0 in 1999.) The Nôm Na Group, led by Ngô Thanh Nhàn, published a set of nearly 20,000 Nôm characters in 2005.[92] This set includes both the characters proposed earlier and a large group of additional characters referred to as "V6".[90] These are mainly Han characters from Trần Văn Kiệm's dictionary which were already assigned code points. Character readings were determined manually by Hồng's group, while Nhàn's group developed software for this purpose.[93] The work of the two groups was integrated and published in 2008 as the Hán Nôm Coded Character Repertoire.[93]

| Character | Composition | Nôm reading | Sino-Vietnamese reading | Meaning | Code point | V Source | Other sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 吧 | ⿰口巴 | và | ba | (slightly formal) and | U+5427 | V0-3122 | G0,J,KP,K,T |

| 傷 | ⿰亻⿱𠂉昜 | thương | thương | wound, injury, to love non-romantically | U+50B7 | V1-4C22 | G1,J,KP,K,T |

| 𠊛 | ⿰㝵人 | người | N/A | people | U+2029B | V2-6E4F | None |

| 㤝 | ⿰忄充 | suông | song | plain, bland | U+391D | V3-313D | G3,KP,K,T |

| 𫋙 | ⿰虫強 | càng | N/A | claw, pincer | U+2B2D9 | V4-536F | None |

| 𫡯[g] | ⿰朝乙 | chàu | N/A | wealth | U+2B86F | V4-405E | None |

| Key: G0 = China (GB 2312); G1 = China (GB 12345); G3 = China (GB 7589); GHZ = Hanyu Da Zidian; J = Japan; KP= North Korea; K = South Korea; T = Taiwan. Sources: Unihan Database, Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation, "Code Charts – CJK Ext. E" (N4358-A).[91] The Han-Viet readings are from Hán Việt Từ Điển. | |||||||

The characters that do not exist in Chinese have Sino-Vietnamese readings that are based on the characters given in parentheses. The common character for càng (強) contains the radical 虫 (insects).[94] This radical is added redundantly to create 𫋙, a rare variation shown in the chart above. The character 𫡯 (chàu) is specific to the Tày people.[95] It has been part of the Unicode standard only since version 8.0 of June 2015, so there is still very little font and input method support for it. It is a variation of 朝, the corresponding character in Vietnamese.[96]

See also

Notes

- ^ The reconstruction of Middle Chinese used here is Baxter's transcription for Middle Chinese.

- ^ The word is still used in some dialects of Vietnamese, and is found fossilized in some words such as gà cồ 𪃿瞿 and cồ cộ 瞿椇. It is also used with the meaning of 'big' in the text, Cư Trần lạc đạo phú 居塵樂道賦, Đệ thất hội 第七會, where it reads 勉德瞿經裴兀扲戒咹㪰 (Mến đức cồ kiêng bùi ngọt cầm giới ăn chay). Other variant characters for cồ include 𡚝 (⿱大瞿) and 𬯵 (⿱賏瞿).

- ^ The Hộ Thành Sơn inscription was mentioned by Henri Maspero.[38] This mention was often cited, including by DeFrancis and Thompson, but according to Nguyễn Đình Hoà no-one has been able to find the inscription that Maspero referred to.[35]

- ^ The original line in the Chinese version is 人不學,不知義.

- ^ Properly written 本𖿱. The cá and nháy marks were added to the Ideographic Symbols and Punctuation block in Unicode 13.0, but they are poorly supported as of April 2021. ‹ is a visual approximation.

- ^ The character 媄 is also used in Chinese as an alternate form of 美 'beautiful'.

- ^ This character is only used in the Tày language, the Vietnamese variant is 𢀭 giàu.

References

- ^ Li 2020, p. 102.

- ^ Kornicki 2017, p. 569.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 252.

- ^ Sun 2015, pp. 552–553.

- ^ Nguyễn, Khuê (2009). Chữ Nôm: cơ sở và nâng cao. Nhà xuất bản Đại học Quốc gia Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. p. 5.

- ^ Li 2020, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Hannas 1997, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b DeFrancis 1977, pp. 32, 38.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 26.

- ^ Nguyễn, Tài Cẩn (1995). Giáo trình lịch sử ngữ âm tiếng Việt (sơ thảo). Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục. p. 47.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 27.

- ^ Nguyễn, Khuê (2009). Chữ Nôm: cơ sở và nâng cao. Nhà xuất bản Đại học Quốc gia Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. pp. 5, 215.

- ^ ""Mi ở Quảng Nôm hay Quảng Nam?"". Người Quảng Nam. 6 August 2016.

- ^ Vũ, Văn Kính (2005). Đại tự điển chữ Nôm. Nhà xuất bản Văn nghệ Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. pp. 293, 899.

- ^ Nguyễn, Hữu Vinh; Đặng, Thế Kiệt; Nguyễn, Doãn Vượng; Lê, Văn Đặng; Nguyễn, Văn Sâm; Nguyễn, Ngọc Bích; Trần, Uyên Thi (2009). Tự điển chữ Nôm trích dẫn. Viện Việt-học. pp. 248, 249, 866.

- ^ Nguyễn, Tài Cẩn (2001). Nguồn gốc và quá trình hình thành cách đọc Hán Việt. Nhà xuất bản Đại học quốc gia Hà Nội. p. 16.

- ^ Hội Khai-trí tiến-đức (1954). Việt-nam tự-điển. Văn Mới. pp. 141, 228.

- ^ Đào, Duy Anh (2005). Hán-Việt từ-điển giản yếu. Nhà xuất bản Văn hoá Thông tin. p. 281.

- ^ Hội Khai-trí tiến-đức (1954). Việt-nam tự-điển. Văn Mới. p. 228.

- ^ Đào, Duy Anh (2005). Hán-Việt từ-điển giản yếu. Nhà xuất bản Văn hoá Thông tin. pp. 281, 900.

- ^ Trần, Văn Chánh (January 2012). "Tản mạn kinh nghiệm học chữ Hán cổ". Suối Nguồn, Tập 3&4. Nhà xuất bản Tổng hợp Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh: 82.

- ^ Asian research trends: a humanities and social science review – No 8 to 10 – Page 140 Yunesuko Higashi Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) – 1998 "Most of the source materials from premodern Vietnam are written in Chinese, obviously using Chinese characters; however, a portion of the literary genre is written in Vietnamese, using chu nom. Therefore, han nom is the term designating the whole body of premodern written materials.."

- ^ Vietnam Courier 1984 Vol20/21 Page 63 "Altogether about 15,000 books in Han, Nom and Han—Nom have been collected. These books include royal certificates granted to deities, stories and records of deities, clan histories, family genealogies, records of cutsoms, land registers, ..."

- ^ Khắc Mạnh Trịnh, Nghiên cứu chữ Nôm: Kỷ yếu Hội nghị Quốc tế về chữ Nôm Viện nghiên cứu Hán Nôm (Vietnam), Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation – 2006 "The Di sản Hán Nôm notes 366 entries which are solely on either medicine or pharmacy; of these 186 are written in Chinese, 50 in Nôm, and 130 in a mixture of the two scripts. Many of these entries ... Vietnam were written in either Nôm or Hán-Nôm rather than in 'pure' Chinese. My initial impression was that the percentage of texts written in Nôm was even higher. This is because for the particular medical subject I wished to investigate-smallpox-the percentage of texts written in Nom or Hán-Nôm is even higher than is the percentage of texts in Nôm and Hán-Nôm for general medical and pharmaceutical .."

- ^ Wynn Wilcox Vietnam and the West: New Approaches 2010– Page 31 "At least one Buddhist text, the Cổ Châu Pháp Vân phật bản hạnh ngữ lục (CCPVP), preserves a story in Hán script about the early years of Buddhist influence in Vietnam and gives a parallel Nôm translation."

- ^ a b Hannas 1997, pp. 78–79, 82.

- ^ Marr 1984, p. 141: "Because the Chinese characters were pronounced according to Vietnamese preferences, and because certain stylistic modifications occurred over time, later scholars came to refer to a hybrid "Sino-Vietnamese" (Han-Viet) language. However, there would seem to be no more justification for this term than for a fifteenth-century "Latin-English" versus the Latin written contemporaneously in Rome."

- ^ a b Marr 1984, p. 141.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Keith Weller Taylor The Birth of Vietnam 1976 – Page 220 "The earliest example of Vietnamese character writing, as we have noted earlier, is for the words bo and cai in the posthumous title given to Phung Hung."

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kiernan 2017, p. 141.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kiernan 2017, p. 138.

- ^ a b Nguyễn 1990, p. 395.

- ^ a b c DeFrancis 1977, p. 23.

- ^ Laurence C. Thompson A Vietnamese Reference Grammar 1987 Page 53 "This stele at Ho-thành-sơn is the earliest irrefutable piece of evidence of this writing system, which is called in Vietnamese chữ nôm (chu 'written word', nom 'popular language'), probably ultimately related to nam 'south'-note that the ..."

- ^ Maspero 1912, p. 7, n. 1.

- ^ a b Li 2020, p. 104.

- ^ Nguyễn 1990, p. 396.

- ^ Sesquisyllabicity, Chữ Nôm, and the Early Modern embrace of vernacular writing in Vietnam

- ^ Gong 2019, p. 60.

- ^ Hannas 1997, p. 83: "An exception was during the brief Hồ dynasty (1400–07), when Chinese was abolished and chữ Nôm became the official script, but the subsequent Chinese invasion and twenty-year occupation put an end to that (Helmut Martin 1982:34)."

- ^ Mark W. McLeod, Thi Dieu Nguyen Culture and Customs of Vietnam 2001 Page 68 – "In part because of the ravages of the Ming occupation — the invaders destroyed or removed many Viet texts and the blocks for printing them — the earliest body of nom texts that we have dates from the early post-occupation era ..."

- ^ Mark W. McLeod, Thi Dieu Nguyen, Culture and Customs of Vietnam, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p. 68.

- ^ Viết Luân Chu, Thanh Hóa, thế và lực mới trong thế kỷ XXI, 2003, p. 52

- ^ Phan, John (2013). "Chữ Nôm and the Taming of the South: A Bilingual Defense for Vernacular Writing in the Chỉ Nam Ngọc Âm Giải Nghĩa". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 8 (1). Oakland, California: University of California Press: 1. doi:10.1525/vs.2013.8.1.1. JSTOR 10.1525/vs.2013.8.1.1.

- ^ Kornicki 2017, p. 570.

- ^ B. N. Ngô "The Vietnamese Language Learning Framework" – Journal of Southeast Asian Language and Teaching, 2001 "... to a word, is most frequently represented by combining two Chinese characters, one of which indicates the sound and the other the meaning. From the fifteenth to the nineteenth century many major works of Vietnamese poetry were composed in chữ nôm, including Truyện Kiều"

- ^ Hannas 1997, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Marr 1984, p. 142.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Ostrowski, Brian Eugene (2010). "The Rise of Christian Nôm Literature in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Fusing European Content and Local Expression". In Wilcox, Wynn (ed.). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Ithaca, New York: SEAP Publications, Cornell University Press. pp. 23, 38. ISBN 9780877277828.

- ^ Taberd, J.L. (1838), Dictionarium Anamitico-Latinum Archived 2013-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. This is a revision of a dictionary compiled by Pierre Pigneau de Behaine in 1772–1773. It was reprinted in 1884.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, pp. 101–105.

- ^ Truong, Buu Lâm (1967). Patterns of Vietnamese Response to Foreign Interventions, 1858–1900. Yale Southeast Asian Studies Monograph. Vol. 11. New Haven: Yale University. pp. 99–102.

- ^ Quyền Vương Đình (2002), Văn bản quản lý nhà nước và công tác công văn, giấy tờ thời phong kiến Việt Nam, p. 50.

- ^ Phan Châu Trinh, "Monarchy and Democracy", Phan Châu Trinh and His Political Writings, SEAP Publications, 2009, ISBN 978-0-87727-749-1, p. 126. This is a translation of a lecture Chau gave in Saigon in 1925. "Even at this moment, the so-called "Confucian scholars (i.e. those who have studied Chinese characters, and in particular, those who have passed the degrees of cử nhân [bachelor] and tiến sĩ [doctorate]) do not know anything, I am sure, of Confucianism. Yet every time they open their mouths they use Confucianism to attack modern civilization – a civilization they do not comprehend even a tiny bit."

- ^ a b c d Phùng, Thành Chủng (November 12, 2009). "Hướng tới 1000 năm Thăng Long-Hà Nội" [Towards 1000 years of Thang Long-Hanoi]. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 179.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 205.

- ^ Cordier, Georges (1935), Les trois écritures utilisées en Annam: chu-nho, chu-nom et quoc-ngu (conférence faite à l'Ecole Coloniale, à Paris, le 28 mars 1925), Bulletin de la Société d'Enseignement Mutuel du Tonkin 15: 121.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 218.

- ^ DeFrancis 1977, p. 240.

- ^ Friedrich, Paul; Diamond, Norma, eds. (1994). "Jing". Encyclopedia of World Cultures, volume 6: Russia and Eurasia / China. New York: G.K. Hall. p. 454. ISBN 0-8161-1810-8.

- ^ Đại Việt sử ký tiệp lục tổng tự, NLVNPF-0105 R.2254.

- ^ Shimizu, Masaaki (4 August 2020). "Sino-Vietnamese initials reflected in the phonetic components of 15th-century Nôm character". Journal of Chinese Writing Systems. 4 (3): 183–195. doi:10.1177/2513850220936774 – via SageJournals.

The material used in this study is obviously older than the poems of Nguyễn Trãi and belongs to the text type called giải âm 解音, which includes word-for-word translations of Chinese texts into Vietnamese.

- ^ Xun, Gong (4 March 2020). "Chinese loans in Old Vietnamese with a sesquisyllabic phonology". Journal of Language Relationship. 17 (1–2): 58–59. doi:10.31826/jlr-2019-171-209.

The document, 佛說大報父母恩重經 Phật thuyết Đại báo phụ mẫu ân trọng kinh ("Sūtra explained by the Buddha on the Great Repayment of the Heavy Debt to Parents", henceforth Đại báo), is held in the Société asiatique, Paris. It is a version of a popular Chinese apochyphon more commonly known under the title 父母恩重難報經 Fùmǔ Ēnzhòng Nánbàojīng, Phụ mẫu ân trọng nan báo kinh ("Sūtra on the Difficulty of Repaying the Heavy Debt to Parents"), in which the Chinese text is accompanied by a vernacular translation (called 解音 giải âm in Vietnam) in a rudimentary form of Chữ Nôm, where vernacular words are written with Chinese characters and modified versions thereof.

- ^ a b Phan, John D. (2014-01-01), "4 Rebooting the Vernacular in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam", Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919, Brill, p. 122, doi:10.1163/9789004279278_005, ISBN 978-90-04-27927-8, retrieved 2023-12-20,

Thus, the Literary Sinitic preface overtly claims the present dictionary to be an explication (giải nghĩa 解義) of Sĩ Nhiếp's original work—that is, the vernacular glossary to southern songs and poems entitled Guide to Collected Works (Chỉ nam phẩm vị 指南品彙).

- ^ Marr 1984, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Handel (2019), p. 153.

- ^ a b Hannas 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Pulleyblank 1991, p. 371.

- ^ Pulleyblank 1991, p. 32.

- ^ Pulleyblank 1991, p. 311.

- ^ Pulleyblank 1991, p. 218.

- ^ a b Hannas 1997, p. 80.

- ^ Collins, Lee; Ngô Thanh Nhàn (6 November 2017). "Proposal to Encode Two Vietnamese Alternate Reading Marks" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Hannas 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (7 October 2019). "Research of square scripts in Vietnam: An overview and prospects". Journal of Chinese Writing Systems. 3 (3): 6. doi:10.1177/251385021986116 (inactive 2024-11-02) – via SageJournals.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Hannas 1997, p. 79.

- ^ Li 2020, p. 103.

- ^ Nguyễn, Khuê (2009). Chữ Nôm: cơ sở và nâng cao. Nhà xuất bản Đại học Quốc gia Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. p. 63.

- ^ Nguyễn, Khuê (2009). Chữ Nôm: cơ sở và nâng cao. Nhà xuất bản Đại học Quốc gia Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. p. 56.

- ^ Vũ, Văn Kính (2005). Đại tự điển chữ Nôm. Nhà xuất bản Văn nghệ Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. p. 838.

- ^ "Truyện Kiều – An electronic version". Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation. Retrieved 10 Feb 2021.

- ^ Nguyễn, Du; Huỳnh, Sanh Thông (1983). The Tale of Kieu. Yale University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-300-04051-7.

- ^ Luong Van Phan, "Country Report on Current Status and Issues of e-government Vietnam – Requirements for Documentation Standards". The character list for the 1993 standard is given in Nôm Proper Code Table: Version 2.1 by Ngô Thanh Nhàn.

- ^ "Han Unification History", The Unicode Standard, Version 5.0 (2006).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k (in Vietnamese) Nguyễn Quang Hồng, "Giới thiệu Kho chữ Hán Nôm mã hoá" [Hán Nôm Coded Character Repertoire Introduction], Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation.

- ^ a b "Code Charts – CJK Ext. E", (N4358-A), JTC1/SC2/WG2, Oct. 10, 2012.

- ^ Thanh Nhàn Ngô, Manual, the Nôm Na Coded Character Set, Nôm Na Group, Hanoi, 2005. The set contains 19,981 characters.

- ^ a b Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies and Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation, Kho Chữ Hán Nôm Mã Hoá [Hán Nôm Coded Character Repertoire] (2008).

- ^ (in Vietnamese) Trần Văn Kiệm, Giúp đọc Nôm và Hán Việt [Help with Nom and Sino-Vietnamese], 2004, "Entry càng", p. 290.

- ^ Hoàng Triều Ân, Tự điển chữ Nôm Tày [Nom of the Tay People], 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Detailed information: V+63830", Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation.

"List of Unicode Radicals", VNPF.

Kiệm, 2004, p. 424, "Entry giàu."

Entry giàu", VDict.com.

- Works cited

- DeFrancis, John (1977), Colonialism and language policy in Viet Nam, Mouton, ISBN 978-90-279-7643-7.

- Gong, Xun (2019), "Chinese loans in Old Vietnamese with a sesquisyllabic phonology", Journal of Language Relationship, 17 (1–2): 55–72, doi:10.31826/jlr-2019-171-209.

- Handel, Zev (2019), Sinography: The Borrowing and Adaptation of the Chinese Script, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-38632-7.

- Hannas, Wm. C. (1997), Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017), Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516076-5.

- Kornicki, Peter (2017), "Sino-Vietnamese literature", in Li, Wai-yee; Denecke, Wiebke; Tian, Xiaofen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature (1000 BCE-900 CE), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 568–578, ISBN 978-0-199-35659-1.

- Li, Yu (2020), The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-00-069906-7.

- Marr, David G. (1984), Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920–1945, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-90744-7.

- Maspero, Henri (1912), "Etudes sur la phonétique historique de la langue annamite. Les initiales", Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, 12: 1–124, doi:10.3406/befeo.1912.2713.

- Nguyễn, Đình Hoà (1990), "Graphemic borromings from Chinese: the case of chữ nôm – Vietnam's demotic script" (PDF), Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, 61 (2): 383–432.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin George (1991), Lexicon of reconstructed pronunciation in early Middle Chinese, late Middle Chinese, and early Mandarin, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0366-3.

- Sun, Hongkai (2015), "Language policy of China's minority languages", in Sun, Chaofen; Yang, William (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 541–553, ISBN 978-0-19985-634-3

Further reading

- Chʻen, Ching-ho (n. d.). A Collection of Chữ Nôm Scripts with Pronunciation in Quốc-Ngữ. Tokyo: Keiô University.

- Nguyễn, Đình Hoà (2001). Chuyên Khảo Về Chữ Nôm = Monograph on Nôm Characters. Westminster, California: Institute of Vietnamese Studies, Viet-Hoc Pub. Dept.. ISBN 0-9716296-0-9

- Nguyễn, N. B. (1984). The State of Chữ Nôm Studies: The Demotic Script of Vietnam. Vietnamese Studies Papers. [Fairfax, Virginia]: Indochina Institute, George Mason University.

- O'Harrow, S. (1977). A Short Bibliography of Sources on "Chữ-Nôm". Honolulu: Asia Collection, University of Hawaii.

- Schneider, Paul 1992. Dictionnaire Historique Des Idéogrammes Vietnamiens / (licencié en droit Nice, France : Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, R.I.A.S.E.M.)

- Zhou Youguang 周有光 (1998). Bijiao wenzi xue chutan (比較文字学初探 "A Comparative Study of Writing Systems"). Beijing: Yuwen chubanshe.

- http://www.academia.edu/6797639/Rebooting_the_Vernacular_in_17th-century_Vietnam

External links

- Chunom.org Archived 2020-12-19 at the Wayback Machine "This site is about Chữ Nôm, the classical writing system of Vietnam."

- Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation. Features a character dictionary.

- Chữ Nôm, Omniglot

- The Vietnamese Writing System, Bathrobe's Chinese, Japanese & Vietnamese Writing Systems

- Han-Nom Revival Committee of Vietnam

- (in Vietnamese) VinaWiki – wiki encyclopedia in chữ Nôm with many articles transliterated from the Vietnamese Wikipedia

- (in Vietnamese) Han-Nom Research Institute

- (in Vietnamese) Tự Điển Chữ Nôm Trích Dẫn – Dictionary of Nôm characters with excerpts, Institute of Vietnamese Studies, 2009

- (in Vietnamese) Vấn đề chữ viết nhìn từ góc độ lịch sử tiếng Việt, Trần Trí Dõi

- 越南北屬時期漢字文獻異體字整理與研究

- Chữ Nôm to Vietnamese Latin Converter

- Bianchi, Brent. "Southeast Asia Collection: Hán Nôm Studies 研究漢喃". Yale University Library Research Guides. Yale University. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

Texts

- "The Hán-Nôm Special Collection Digitization Project". Southeast Asia Digital library. Northern Illinois University.

- The Digital Library of Hán-Nôm, digitized manuscripts held by the National Library of Vietnam.

Software

There are a number of software tools that can produce chữ Nôm characters simply by typing Vietnamese words in chữ quốc ngữ:

- HanNomIME, a Windows-based Vietnamese keyboard driver that supports Hán characters and chữ Nôm.

- Vietnamese Keyboard Set which enables chữ Nôm and Hán typing on Mac OS X.

- WinVNKey, a Windows-based Vietnamese multilingual keyboard driver that supports typing chữ Nôm in addition to Traditional and Simplified Chinese.

- Chunom.org Online Editor, a browser-based editor for typing chữ Nôm.

- Bộ gõ Hán Nôm: Phương Viên, a rime-based IME for typing chữ Nôm.

Other entry methods:

- (in Chinese) 倉頡之友《倉頡平台2012》 Archived 2013-12-14 at the Wayback Machine Cangjie input method for Windows that allows keyboard entry of all Unicode CJK characters by character shape. Supports over 70,000 characters. Users may add their own characters and character combinations.

Fonts

Fonts with a sufficient coverage of Chữ Nôm characters include Han-Nom Gothic, Han-Nom Minh, Han-Nom Ming, Han-Nom Kai, Nom Na Tong, STXiHei (Heiti TC), MingLiU plus MingLiU-ExtB, Han Nom A plus Han Nom B, FZKaiT-Extended plus FZKaiT-Extended(SIP), and Mojikyō fonts which require special software. The following web pages are collections of URLs from which Chữ Nôm capable fonts can be downloaded:

- Fonts for Chu Nom on chunom.org.

- Han-Nom Fonts on hannom-rcv.org.