My Sweet Lord

| "My Sweet Lord" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Original UK and US cover | ||||

| Single by George Harrison | ||||

| from the album All Things Must Pass | ||||

| A-side | "Isn't It a Pity" (US) (double A-side) | |||

| B-side | "What Is Life" (UK) | |||

| Released | 23 November 1970 (US) 15 January 1971 (UK) | |||

| Genre | Folk rock, gospel, pop[1] | |||

| Length | 4:39 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison | |||

| Producer(s) | George Harrison, Phil Spector | |||

| George Harrison singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| George Harrison singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

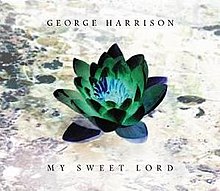

| Alternative cover | ||||

2002 reissue cover | ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "My Sweet Lord" on YouTube | ||||

"My Sweet Lord" is a song by the English musician George Harrison, released in November 1970 on his triple album All Things Must Pass. It was also released as a single, Harrison's first as a solo artist, and topped charts worldwide; it was the biggest-selling single of 1971 in the UK. In America and Britain, the song was the first number-one single by an ex-Beatle. Harrison originally gave the song to his fellow Apple Records artist Billy Preston to record; this version, which Harrison co-produced, appeared on Preston's Encouraging Words album in September 1970.

Harrison wrote "My Sweet Lord" in praise of the Hindu god Krishna,[2] while intending the lyrics as a call to abandon religious sectarianism through his blending of the Hebrew word hallelujah with chants of "Hare Krishna" and Vedic prayer.[3] The recording features producer Phil Spector's Wall of Sound treatment and heralded the arrival of Harrison's slide guitar technique, which one biographer described as "musically as distinctive a signature as the mark of Zorro".[4] Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton, Gary Brooker, Bobby Whitlock and members of the group Badfinger are among the other musicians on the recording.

Later in the 1970s, "My Sweet Lord" was at the centre of a heavily publicised copyright infringement suit due to its alleged similarity to the Ronnie Mack song "He's So Fine", a 1963 hit for the New York girl group the Chiffons. In 1976, Harrison was found to have subconsciously plagiarised the song, a verdict that had repercussions throughout the music industry. Rather than the Chiffons song, he said he used the out-of-copyright Christian hymn "Oh Happy Day" as his inspiration for the melody.

Harrison performed "My Sweet Lord" at the Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, and it remains the most popular composition from his post-Beatles career. He reworked it as "My Sweet Lord (2000)" for inclusion as a bonus track on the 30th-anniversary reissue of All Things Must Pass. Many artists have covered the song, most notably Edwin Starr, Johnny Mathis and Nina Simone. "My Sweet Lord" was ranked 454th on Rolling Stone's list of "the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time" in 2004 and 460th in the 2010 update and number 270 on a similar list published by the NME in 2014. It reached number one in Britain again when re-released in January 2002, two months after Harrison's death.

Background and inspiration

George Harrison began writing "My Sweet Lord" in December 1969, when he, Billy Preston and Eric Clapton were in Copenhagen, Denmark,[4][5] as guest artists on Delaney & Bonnie's European tour.[6][7] By this time, Harrison had already written the gospel-influenced "Hear Me Lord" and, with Preston, the African-American spiritual "Sing One for the Lord".[8] He had also produced two religious-themed hit singles on the Beatles' Apple record label: Preston's "That's the Way God Planned It" and Radha Krishna Temple (London)'s "Hare Krishna Mantra".[6][9] The latter was a musical adaptation of the 5,000-year-old Vaishnava Hindu mantra, performed by members of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), colloquially known as "the Hare Krishna movement".[10][11] Harrison wanted to fuse the messages of the Christian and Gaudiya Vaishnava faiths[12] into what musical biographer Simon Leng terms "gospel incantation with a Vedic chant".[5]

The Copenhagen stopover marked the end of the Delaney & Bonnie tour, with a three-night residency at the Falkoner Theatre on 10–12 December.[13] According to Harrison's 1976 court testimony, "My Sweet Lord" was conceived while the band members were attending a backstage press conference and he had ducked out to an upstairs room at the theatre.[14] Harrison recalled vamping chords on guitar and alternating between sung phrases of "hallelujah" and "Hare Krishna".[15][16] He later took the idea to the others, and the chorus vocals were developed further.[14]

Band leader Delaney Bramlett's later version of events is that the idea originated from Harrison asking him how to go about writing a genuine gospel song,[7] and that Bramlett demonstrated by scat singing the words "Oh my Lord" while wife Bonnie and singer Rita Coolidge added gospel "hallelujah"s in reply.[17] Music journalist John Harris has questioned the accuracy of Bramlett's account, however, comparing it to a fisherman's "It was this big"–type bragging story.[7] Preston recalled that "My Sweet Lord" came about through Harrison asking him about writing gospel songs during the tour. Preston said he played some chords on a backstage piano and the Bramletts began singing "Oh my Lord" and "Hallelujah". According to Preston: "George took it from there and wrote the verses. It was very impromptu. We never thought it would be a hit."[18]

Using as his inspiration the Edwin Hawkins Singers' rendition of an eighteenth-century Christian hymn, "Oh Happy Day",[4][19] Harrison continued working on the theme.[20] He completed the song, with help from Preston, once they had returned to London.[15][16]

Composition

The lyrics of "My Sweet Lord" reflect Harrison's often-stated desire for a direct relationship with God, expressed in simple words that all believers could affirm, regardless of their religion.[21][22] He later attributed the song's message to Swami Vivekananda,[23] particularly the latter's teaching: "If there's a God, we must see him. And if there is a soul, we must perceive it."[24] Author Ian Inglis observes a degree of "understandable" impatience in the first verse's line "Really want to see you, Lord, but it takes so long, my Lord".[21] By the end of the song's second verse, Harrison declares a wish to "know" God also[25][26] and attempts to reconcile the impatience.[21]

"My Sweet Lord" has got a mantra in there and mantras are – well, they call it a mystical sound vibration encased in the syllable ... Once I chanted it for like three days non-stop, driving through Europe, and you just get hypnotised ...[27]

Following this verse, in response to the main vocal's repetition of the song title, Harrison devised a choral line singing the Hebrew word of praise, "hallelujah", common in the Christian and Jewish religions.[19] Later in the song, after an instrumental break, these voices return, now chanting the first twelve words of the Hare Krishna mantra, known more reverentially as the Maha mantra:[10][19]

Hare Rama, Hare Rama

Rama Rama Hare Hare

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna

Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare

These Sanskrit words are the main mantra of the Hare Krishna faith, with which Harrison identified,[6][28][29] although he did not belong to any spiritual organisation.[30][31] In his 1980 autobiography, I, Me, Mine, Harrison says that he intended repeating and alternating "hallelujah" and "Hare Krishna" to show that the two terms meant "quite the same thing",[20] as well as to have listeners chanting the mantra "before they knew what was going on!"[32]

Following the Sanskrit lines, "hallelujah" is sung twice more before the mantra repeats,[33] along with an ancient Vedic prayer.[25] According to Hindu tradition, this prayer is dedicated to a devotee's spiritual teacher, or guru, and equates the teacher to the divine Trimurti – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva (or Maheshvara) – and to the Godhead, Brahman.[34]

Gurur Brahmā, gurur Viṣṇur

gurur devo Maheśvaraḥ

gurus sākṣāt, paraṃ Brahma

tasmai śrī gurave namaḥ.

Religious academic Joshua Greene, one of the Radha Krishna Temple devotees in 1970, translates the lines as follows: "I offer homage to my guru, who is as great as the creator Brahma, the maintainer Vishnu, the destroyer Shiva, and who is the very energy of God."[35] The prayer is the third verse of the Guru Stotram, a fourteen-verse hymn in praise of Hindu spiritual teachers.[36][nb 1]

Several commentators cite the mantra and the simplicity of Harrison's lyrics as central to the song's universality.[21][38] In Inglis's view, "[The] lyrics are not directed at a specific manifestation of a single faith's deity, but rather to the concept of one god whose essential nature is unaffected by particular interpretations and who pervades everything, is present everywhere, is all-knowing and all-powerful, and transcends time and space ... All of us – Christian, Hindu, Muslim, Jew, Buddhist – can address our gods in the same way, using the same phrase ['my sweet Lord']."[21]

Billy Preston's version

| "My Sweet Lord" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Billy Preston | ||||

| from the album Encouraging Words | ||||

| B-side | "Little Girl" | |||

| Released | 3 December 1970 | |||

| Genre | Soul, gospel | |||

| Length | 3:21 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison | |||

| Producer(s) | George Harrison, Billy Preston | |||

| Billy Preston singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

With the Beatles still together officially in December 1969, Harrison had no plans to make a solo album of his own and reportedly intended to offer "My Sweet Lord" to Edwin Hawkins.[39][40] Instead, following the Delaney & Bonnie tour, he decided to record it with Billy Preston,[4] for whom Harrison was co-producing a second Apple album, Encouraging Words.[41][42] Recording took place at Olympic Studios in London, in January 1970,[8] with Preston as principal musician,[16] supported by the guitarist, bass player and drummer from the Temptations' backing band.[12] The Edwin Hawkins Singers happened to be on tour in the UK as well, so Harrison invited them to participate.[12][39][nb 2]

Preston's version of "My Sweet Lord" differs from Harrison's later reading in that the "hallelujah" refrain appears from the start of the song and, rather than the full mantra section, the words "Hare Krishna" are sung only twice throughout the whole track.[12] With the Vedic prayer also absent, Leng views this original recording as a possible "definitive 'roots' take'" of the song, citing its "pure gospel groove" and Hawkins' participation.[5] In his review of Encouraging Words, Bruce Eder of AllMusic describes "My Sweet Lord" and "All Things Must Pass" (another Harrison composition originally given to Preston to record)[43] as "stunning gospel numbers ... that make the Harrison versions seem pallid".[44]

Preston's "My Sweet Lord" was a minor hit in Europe when issued as a single there in September 1970,[43] but otherwise, Encouraging Words made little impression commercially.[44][45] The album and single releases were delayed for at least two months in the United States. There, "My Sweet Lord" climbed to number 90 on the Billboard Hot 100 by the end of February 1971,[46] helped by the enormous success of Harrison's version.[47] Preston's single also peaked at number 23 on Billboard's Best Selling Soul Singles chart.[48] In March 1971, he recorded a live version with King Curtis that was released in 2006 on the expanded edition of Curtis's album Live at Fillmore West.[49]

Recording

Basic track

Five months after the Olympic session, with the Beatles having broken up in April 1970, "My Sweet Lord" was one of 30 or more tracks that Harrison recorded for his All Things Must Pass triple album.[50] He was initially reluctant to record the song, for fear of committing himself to such an overt religious message.[32][51] In I, Me, Mine, he states: "I was sticking my neck out on the chopping block because now I would have to live up to something, but at the same time I thought 'Nobody's saying it; I wish somebody else was doing it.'"[20]

Principal recording took place at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) in London, with Phil Spector co-producing the sessions.[52] Phil McDonald was the recording engineer for the basic track.[53] It was taped on 28 May, the first day of formal recording for All Things Must Pass, after "Wah-Wah".[54] Having assembled a large cast of backing musicians for the sessions, Harrison initially recorded five takes of "My Sweet Lord" with just acoustic guitars and harmonium before changing to a full band arrangement.[55]

The line-up of musicians on the song has been hard to ascertain due to the lack of available studio documentation and conflicting recollections over the ensuing decades.[51][56] The musicians were requested by Harrison and booked by former Beatles roadie Mal Evans, acting in a role that Beatles scholar Kenneth Womack likens to a stage manager for the project. According to Womack and his co-author Jason Kruppa, Evans' diaries from the period provide the first reliable record of the participants at the All Things Must Pass sessions, since Evans paid the musicians and had to justify this expenditure to Apple.[57]

Harrison said that the musicians included "about five" acoustic guitarists, Ringo Starr and Jim Gordon on drums,[39] two piano players and a bassist.[58] Evans' diary entry for 28 May lists the players on "My Sweet Lord" as Harrison, Eric Clapton and Badfinger guitarists Pete Ham and Joey Molland, all on acoustic guitars; Gary Brooker on piano; Bobby Whitlock on harmonium; Klaus Voormann on bass; Starr on drums; and Alan White on tambourine.[59][nb 3]

Harrison recalled working hard with the other acoustic guitarists "to get them all to play exactly the same rhythm so it just sounded perfectly in sync".[58] To achieve the resonant guitar sound on this and other All Things Must Pass tracks, Molland said that he and his bandmates were partitioned off inside a plywood structure.[63][nb 4] McDonald put what he terms a "half soundproof box" around Harrison, to help capture his acoustic guitar.[54]

Overdubs

"My Sweet Lord" must have taken about twelve hours to overdub the guitar solos. He must have had that in triplicate, six-part harmony, before we decided on two-part harmony. Perfectionist is not the word ... He was beyond that. He just had to have it so right. He would try and try and experiment upon experiment ... He'd do the same with the background vocals.[64]

Take 16 of "My Sweet Lord" was selected for overdubs.[54] From late July onwards,[65] Harrison and Peter Frampton added further acoustic guitars to the song[66] and to other tracks from the album.[67][68] The chorus vocals were all sung by Harrison and credited to "the George O'Hara-Smith Singers".[32][69][nb 5] These contributions, together with Harrison's slide guitar parts and Barham's orchestral arrangement, were overdubbed during the next two months,[64] partly at Trident Studios in central London with engineer Ken Scott.[39][71]

Harrison experimented with several harmony ideas in his guitar parts,[72] having first applied himself to mastering slide during the 1969 Delaney & Bonnie tour.[73] Scott had to extend the original track, repeating a portion of the final section, to allow for the closing prayer and fadeout.[74] The session for Barham's string arrangement took place on 18 September, involving 22 orchestral musicians.[75]

Arrangement

Harrison biographer Simon Leng describes the completed recording as a "painstakingly crafted tableau" of sound, beginning with a bank of "chiming" acoustic guitars and the "flourish" of zither strings that introduces Harrison's slide-guitar motif.[76] At close to the two-minute mark, after the tension-building bridge, a subtle two-semitone shift in key (from E major to the rarely used key of F♯ major, via a C♯ dominant seventh chord) signals the song's release from its extended introduction.[77] This higher register is then complemented by Harrison's "increasingly impassioned" vocal, according to Inglis, and the subsequent "timely reappearance" of his twin slide guitars,[21] before the backing vocals switch to the Sanskrit mantra and prayer.[33] Leng comments on the Indian music aspects of the arrangement, in the "swarmandal-like" zithers, representing the sympathetic strings of a sitar, and the slide guitars' evocation of sarangi, dilruba and other string instruments.[78] In an interview for Martin Scorsese's 2011 documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Spector recalls that he liked the results so much, he insisted that "My Sweet Lord" be the lead single from the album.[79]

This rock version of the song was markedly different from the "Oh Happy Day"-inspired gospel arrangement in musical and structural terms,[8] aligning Harrison's composition with pop music conventions, but also drawing out the similarities of its melody line with that of the Chiffons' 1963 hit "He's So Fine".[4] Beatles historian Bruce Spizer writes that this was due to Harrison being "so focused on the feel of his record",[80] while Record Collector editor Peter Doggett wrote in 2001 that, despite Harrison's inspiration for "My Sweet Lord" having come from "Oh Happy Day", "in the hands of producer and arranger Phil Spector, it came out as a carbon copy of the Chiffons' [song]".[81] Chip Madinger and Mark Easter rue that Spector, as "master of all that was 'girl-group' during the early '60s", failed to recognise the similarities.[39]

Release

Before arriving in New York on 28 October to carry out mastering on All Things Must Pass, Harrison had announced that no single would be issued – so as not to "detract from the impact" of the album.[82] Apple's US executive, Allan Steckler, surprised him by insisting that not only should Harrison abandon thoughts of paring down his new material into a single LP, but there were three sure-fire hit singles: "My Sweet Lord", "Isn't It a Pity" and "What Is Life".[83] Spector said that he had to "fight" Harrison and the latter's manager, Allen Klein, to ensure that "My Sweet Lord" was issued as the single.[79] Film director Howard Worth recalls a preliminary finance meeting for the Raga documentary (for which Harrison would provide emergency funding through Apple Films)[84] that began with the ex-Beatle asking him to listen to a selection of songs and pick his favourite, which was "My Sweet Lord".[85] The song was selected even though Preston's version was already scheduled for release as a single in America the following month.[51]

Harrison was opposed to the release, but relented to Apple's wishes.[86] "My Sweet Lord" was issued as the album's lead single around the world, but not in Britain;[79] the release date was 23 November 1970 in the United States.[87] The mix of the song differed from that found on All Things Must Pass by featuring less echo and a slightly altered backing-vocal track.[39][51] Both sides of the North American picture sleeve consisted of a Barry Feinstein photo of Harrison taken through a window at his recently purchased Friar Park home, with some of the estate's trees reflected in the glass.[80] Released as a double A-side with "Isn't It a Pity", with Apple catalogue number 2995 in America, both sides of the disc featured a full Apple label.[80]

Public demand via constant airplay in Britain led to a belated UK release,[88] on 15 January 1971.[89] There, as Apple R 5884, the single was backed by "What Is Life", a song that Apple soon released elsewhere internationally as the follow-up to "My Sweet Lord".[90]

Impact and commercial performance

All Things Must Pass was an unconditional triumph for Harrison ... "My Sweet Lord" was everything that people wanted to hear in November 1970: shimmering harmonies, lustrous acoustic guitars, a solid Ringo Starr backbeat, and an exquisite [Harrison] guitar solo.[38]

Harrison's version of "My Sweet Lord" was an international number 1 hit by the end of 1970 and through the early months of 1971.[91] It was the first solo single by a Beatle to reach the top,[92] and the biggest seller by any of the four throughout the 1970s.[93][94] Without the support of any concert appearances or promotional interviews by Harrison, the single's commercial success was due to its impact on radio,[40] where, Harrison biographer Gary Tillery writes, the song "rolled across the airwaves like a juggernaut, with commanding presence, much the way Dylan's 'Like a Rolling Stone' had arrived in the mid-sixties".[95] Elton John recalled first hearing "My Sweet Lord" in a taxi and named it as the last of the era's great singles: "I thought, 'Oh my God,' and I got chills. You know when a record starts on the radio, and it's great, and you think, 'Oh, what is this, what is this, what is this?' The only other record I ever felt that way about [afterwards] was 'Brown Sugar' ..."[96]

Writing for Rolling Stone in 2002, Mikal Gilmore said "My Sweet Lord" was "as pervasive on radio and in youth consciousness as anything the Beatles had produced".[97] The release coincided with a period when religion and spirituality had become a craze among Western youth, as songs by Radha Krishna Temple and adaptations of the Christian hymns "Oh Happy Day" and "Amazing Grace" were all worldwide hits,[98] even as church attendance continued to decline.[92][nb 6] Harrison's song popularised the Hare Krishna mantra internationally,[100] further to the impact of the Radha Krishna Temple's 1969 recording.[28] In response to the heavy radio play, letters poured into the London temple from around the world, thanking Harrison for his religious message in "My Sweet Lord".[101][nb 7] According to music historian Andrew Grant Jackson, the single's impact surpassed that of any other song in the era's spiritual revival, and Harrison's Indian-influenced slide playing, soon heard also in recordings by Lennon, Starr and Badfinger, was one of the most distinctive sounds of the early 1970s.[103]

The single was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America on 14 December 1970 for sales of over 1 million copies.[40][104] It reached number 1 on the US Billboard Hot 100 on 26 December,[105] remaining on top for four weeks, three of which coincided with All Things Must Pass's seven-week run atop the Billboard albums chart.[106][107] While Billboard recognised both sides of the single in the US,[108] only "Isn't It a Pity" was listed when the record topped Canada's RPM 100 chart.[109]

In Britain, "My Sweet Lord" entered the charts at number 7, before hitting number 1 on 30 January[110] and staying there for five weeks.[111] It was the biggest-selling single of 1971 in the UK[112][113] and performed similarly well around the world,[69] particularly in France and Germany, where it held the top spot for nine and ten weeks, respectively.[114] In his 2001 appraisal of Harrison's Apple recordings, for Record Collector, Doggett described Harrison as "arguably the most successful rock star on the planet" over this period, adding: "'My Sweet Lord' and All Things Must Pass topped charts all over the world, easily outstripping other solo Beatles projects later in the year, such as Ram and Imagine."[91]

The single's worldwide sales amounted to 5 million copies by 1978, making it one of the best-selling singles of all time.[114] By 2010, according to Inglis, "My Sweet Lord" had sold over 10 million copies.[115] The song returned to the number 1 position again in the UK when reissued in January 2002, two months after Harrison's death from cancer at the age of 58.[111]

Contemporary critical reception

Reviewing the single for Rolling Stone, Jon Landau called the track "sensational".[116] Billboard's reviewer described the record as "a powerhouse two-sided winner", saying that "My Sweet Lord" had the "potent feel and flavor of another 'Oh Happy Day'", with powerful lyrics and an "infectious rhythm".[117] Record World called it "a haunting inspirational hare krishna chant-song to a tune reminiscent of the Chiffons' 'He's So Fine.'"[118] Ben Gerson of Rolling Stone commented that the substituting of Harrison's "Hare Krishna" refrain for the trivial "Doo-lang, doo-lang, doo-lang"s of "He's So Fine" was "a sign of the times"[119] and recognised Harrison as "perhaps the premier studio musician among rock band guitarists".[92][nb 8] In his December 1970 album review for NME, Alan Smith bemoaned the apparent lack of a UK single release for "My Sweet Lord". Smith said the song "seems to owe something" to "He's So Fine",[120][121] and Gerson called it an "obvious re-write".[119]

Led by the single, the album encouraged widespread recognition of Harrison as a solo artist and revised views of the nature of the Beatles' creative leadership.[116] Among these writers,[122] Don Heckman of The New York Times predicted that "My Sweet Lord" / "Isn't It a Pity" would soon top the US charts and credited Harrison with having "generated some of the major changes in the style and substance of the Beatles" through his championing of Indian music and Eastern religion.[123]

In a January 1971 review for NME, Derek Johnson expressed surprise at Apple's delay in releasing the single in the UK, and stated: "In my opinion, this record – finally and irrevocably – establishes George as a talent equivalent to either Lennon or McCartney."[121] David Hughes of Disc and Music Echo said he had run out of superlatives to describe the two sides. He deemed "My Sweet Lord" "the most instant and the most commercial" track on All Things Must Pass, adding that the single release was long overdue and a solution for those put off by the high price of the triple LP. Hughes also wrote: "A great rhythm is set up and then comes that superb steel guitar with which he's so fallen in love ... [The track] does sound like the old Chiffons' song 'He's So Fine', but that's not a knock, just a cocky observation."[124]

At the end of 1971, "My Sweet Lord" topped the Melody Maker reader's polls for both "Single of the Year" and "World's Single of the Year".[125] It was also voted "Single of the Year" in a poll conducted by Radio Luxembourg.[126] In the US publication Record World, the song was voted best single and Harrison was named as "Top Male Vocalist of 1971".[113] In June 1972, Harrison won two Ivor Novello songwriter's awards for "My Sweet Lord".[127]

Copyright infringement suit

Initial action

On 10 February 1971, Bright Tunes Music Corporation filed suit against Harrison and associated organisations (including Harrisongs, Apple Records and BMI), alleging copyright infringement of the late Ronnie Mack's song "He's So Fine".[16] In I Me Mine, Harrison admits to having thought "Why didn't I realise?" when others started pointing out the similarity between the two songs.[20] By June that year, country singer Jody Miller had released a cover of "He's So Fine" incorporating Harrison's "My Sweet Lord" slide-guitar riffs,[128] thereby "really putting the screws in" from Harrison's point of view.[129] At this time, Bright Tunes were themselves the subject of litigation, as Mack's mother had sued the company over non-payment of royalties.[130] Allen Klein entered into negotiations with Bright Tunes, offering to buy its entire catalogue, but no settlement could be reached before the company was forced into receivership.[16]

Musicologist Dominic Pedler writes that both songs have a three-syllable title refrain followed by a 5-3-2 descent of the major scale in the tonic key (E major for "My Sweet Lord" and G major for "He's So Fine"); respective tempos are similar: 121 and 145 beats per minute.[131] In the respective B sections ("I really want to see you" and "I dunno how I'm gonna do it"), there is a similar ascent through 5-6-8, but the Chiffons distinctively retain the G tonic for four bars and, on the repeat of the motif, uniquely go to an A-note 9th embellishment over the first syllable of "gonna".[77] Harrison, on the other hand, introduces the more complex harmony of a relative minor (C#m), as well as the fundamental and distinctly original slide-guitar motif.[77]

While the case was on hold, Harrison and his former bandmates Lennon and Starr chose to sever ties with Klein at the end of March 1973 – an acrimonious split that led to further lawsuits for the three ex-Beatles.[132] Bright Tunes and Harrison later resumed their negotiations. His final offer of 40 per cent of "My Sweet Lord"'s US composer's and publisher's royalties, along with a stipulation that he retain copyright for his song, was viewed as a "good one" by Bright's legal representation, yet the offer was rejected.[129] It later came to light that Klein had renewed his efforts to purchase the ailing company, now solely for himself, and to that end was supplying Bright Tunes with insider details regarding "My Sweet Lord"'s sales figures and copyright value.[16][133]

According to journalist Bob Woffinden, writing in 1981, the case would most likely have been settled privately, as so many had been in the past, had Mack still been alive and had "personal ownership of the copyright" been a factor.[134] In the build-up to the case going to court, the Chiffons recorded a version of "My Sweet Lord" in 1975, with the aim of drawing attention to the lawsuit.[128] Author Alan Clayson has described the plagiarism suit as "the most notorious civil action of the decade",[135] saying that the "extremity" of the proceedings were provoked by a combination of the commercial success of Harrison's single and the intervention of "litigation-loving Mr Klein".[130]

Court hearing and ruling

Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music went to the United States district court on 23 February 1976, to hear evidence on the allegation of plagiarism.[16][133] Harrison attended the proceedings in New York, with a guitar, and each side called musical experts to support its argument.[128] Harrison's counsel contended that he had drawn inspiration from "Oh Happy Day" and that Mack's composition was also derived from that hymn. The judge presiding was Richard Owen, a classical musician and composer of operas in his spare time.[136]

After reconvening in September 1976, the court found that Harrison had subconsciously copied "He's So Fine", since he admitted to having been aware of the Chiffons' recording.[137] Owen said in his conclusion to the proceedings:[138]

Did Harrison deliberately use the music of "He's So Fine"? I do not believe he did so deliberately. Nevertheless, it is clear that "My Sweet Lord" is the very same song as "He's So Fine" with different words, and Harrison had access to "He's So Fine". This is, under the law, infringement of copyright, and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished.

Damages and litigation

With liability established, the court recommended an amount for the damages to be paid by Harrison and Apple to Bright Tunes, which Owen totalled at $1,599,987.[139] This figure amounted to three-quarters of the royalty revenue raised in North America from "My Sweet Lord", as well as a significant proportion of that from the All Things Must Pass album.[16] Some observers have considered this unreasonable and unduly harsh,[140] since it underplayed the unique elements of Harrison's recording – the universal spiritual message of its lyrics, the signature guitar hook, and its production – and ignored the acclaim his album received in its own right.[16][141][nb 9] The award factored in the royalty revenue raised from "My Sweet Lord"'s inclusion on the recent Best of George Harrison compilation, though at a more moderate percentage than for the 1970 album.[16] In the UK, the corresponding damages suit, brought by Peter Maurice Music, was swiftly settled out of court in July 1977.[130]

During the drawn-out damages portion of the US suit, events played into Harrison's hands when Klein's ABKCO Industries purchased the copyright to "He's So Fine", and with it all litigation claims,[140] after which Klein proceeded to negotiate sale of the song to Harrison.[16] On 19 February 1981, the court decided that, due to Klein's duplicity in the case, Harrison would only have to pay ABKCO $587,000 instead of the $1.6 million award and would also receive the rights to "He's So Fine" – $587,000 being the amount Klein had paid Bright Tunes for the song in 1978.[16][139] The court ruled that Klein's actions had been in breach of the fiduciary duty owed to Harrison, a duty that continued "even after the principal–agent relationship ended".[16]

The litigation continued through to the early 1990s as the finer points of the settlement were finally decided. In his 1993 essay on Bright Tunes v. Harrisongs, Joseph Self describes it as "without question, one of the longest running legal battles ever to be litigated in [the United States]".[16] Music journalist David Cavanagh termed it "the most absurd legal black comedy in the annals of rock".[143] Matters were concluded in March 1998.[80] Harrison retained the rights for both songs in the UK and North America, and Klein was awarded the rights elsewhere in the world.[49]

Reaction

The ruling set new legal precedents and was a personal blow for Harrison, who said he was too "paranoid" to write anything new for some time afterwards.[144][145][nb 10] Early reaction in the music industry saw Little Richard claim for breach of copyright in a track recorded by the Beatles in 1964 for the Beatles for Sale album,[128] as well as Ringo Starr credit songwriter Clifford T. Ward as the inspiration for his Ringo's Rotogravure song "Lady Gaye".[146]

Look, I'd be willing, every time I write a song, if somebody will have a computer and I can just play any new song into it, and the computer will say, "Sorry" or, "OK". The last thing I want to do is keep spending my life in court.[147]

Shortly before the ruling was handed down in September 1976, Harrison wrote and recorded a song inspired by the court case – the upbeat "This Song".[148] It includes the lines "This tune has nothing 'Bright' about it" and "don't infringe on anyone's copyright".[149] The 1960s soul hits "I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie Honey Bunch)" and "Rescue Me", as well as his own composition "You", are all name-checked in the lyrics,[150] as if to demonstrate the point that, as he later put it, "99 per cent of the popular music that can be heard is reminiscent of something or other."[151][152] In I, Me, Mine, Harrison says of the episode: "I don't feel guilty or bad about it, in fact ['My Sweet Lord'] saved many a heroin addict's life. I know the motive behind writing the song in the first place and its effect far exceeded the legal hassle."[153]

According to Woffinden, the ruling came as no surprise in the US. "He's So Fine" had been a major hit there, unlike in the UK, and American commentators had been quick to scrutinise "My Sweet Lord" for its similarities.[154] Woffinden nevertheless wrote that "within the context of rock music, it was an unjust decision" and that Owen "clearly understood nothing of rock 'n' roll, or gospel, or popular music" in terms of shared influences. Woffinden commented that, as of 1981, no comparable action over copyright infringement had been launched despite the continuation of this tradition; he cited the appropriation of aspects of Harrison's 1966 song "Taxman" in the Jam's recent number 1 hit "Start!" as an example of the industry's preference for avoiding the courtroom.[136][nb 11]

When asked to comment on the decision in a 1976 interview, Starr said: "There's no doubt that the tune is similar but how many songs have been written with other melodies in mind? George's version is much heavier than the Chiffons – he might have done it with the original in the back of his mind, but he's just very unlucky that someone wanted to make it a test case in court."[156] In his 1980 interview with Playboy, John Lennon expressed doubt about the notion of "subconscious" plagiarism, saying of Harrison: "He must have known, you know. He's smarter than that ... He could have changed a couple of bars in that song and nobody could ever have touched him, but he just let it go and paid the price. Maybe he thought God would just sort of let him off."[157][158] McCartney conceded that the Beatles "stole a lot of stuff" from other artists.[159] In a 2008 interview, he said Harrison taking from "He's So Fine" was justified because Harrison had avoided the "boy–girl thing" and offered an important spiritual message.[143]

Retrospective reviews and legacy

AllMusic's Richie Unterberger says of the song's international popularity: "'My Sweet Lord' has a quasi-religious feel, but nevertheless has enough conventional pop appeal to reach mainstream listeners who may or may not care to dig into the spiritual lyrical message."[160] Some Christian fundamentalist anti-rock activists have objected that chanting "Hare Krishna" in "My Sweet Lord" was anti-Christian or Satanic, while some born-again Christians adopted the song as an anthem.[161] Simon Leng describes the slide guitar motif as "among the best-known guitar passages in popular music".[162] Ian Inglis highlights the combination of Harrison's "evident lack of artifice" and Spector's "excellent production", such that "My Sweet Lord" can be heard "as a prayer, a love song, an anthem, a contemporary gospel track, or a piece of perfect pop".[21]

According to music historians David Luhrssen and Michael Larson, "My Sweet Lord" "became an early battleground over music as intellectual property" and the ruling against Harrison "opened a floodgate of suits over allegedly similar melodies and chord progressions".[163] In a 2016 Rolling Stone article on landmark music copyright cases, the suit is credited with establishing "a precedent of harsher copyright standards" as well as "introducing the phrase 'subconscious plagiarism' into the popular lexicon".[164][nb 12] Writing in The New York Review of Books in 2013, author and neurologist Oliver Sacks cited the case when stating his preference for the word cryptomnesia over plagiarism, which he said was "suggestive of crime and deceit". Sacks added that Owen had displayed "psychological insight and sympathy" in deeming Harrison's infringement to have been "subconsciously accomplished".[168]

Due to the plagiarism suit, "My Sweet Lord" became stigmatised.[160][169][170] While acknowledging the similarity with "He's So Fine", music critic David Fricke describes Harrison's composition as "the honest child of black American sacred song".[6] Jayson Greene of Pitchfork writes that the court ruling of subconscious plagiarism "could be a good euphemism for 'pop songwriting'" generally, and the episode was "doubly ironic considering Harrison's intrinsic generosity as an artist".[171] In a 2001 review, Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune said that "My Sweet Lord" serves as the entrance to Spector's "cathedral of sound" on All Things Must Pass, adding that although Harrison lost the lawsuit, the song's "towering majesty ... remains undiminished".[172] Mikal Gilmore calls it an "irresistible devotional".[97] In 2009, pop culture critic Roy Trakin commented that if music fans were in doubt as to Harrison's enduring influence, they should "listen to Wilco's latest album for a song called 'You Never Know', which is even closer to 'My Sweet Lord' than that one was to 'He's So Fine', with its slide guitar lines practically an homage to the original."[173] David Simons of Acoustic Guitar magazine says that, further to his contributions to the Beatles' recordings, Harrison "elevated the sound and scope of recorded acoustic guitar" with his debut single.[63]

In their written tributes to Harrison shortly after his death, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards each named "My Sweet Lord" among their personal favourites of all his songs, along with "While My Guitar Gently Weeps".[174] In 2010, AOL Radio listeners voted it the best song from Harrison's solo years.[175] According to a chart published by PPL in August 2018, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of Apple Records' founding, "My Sweet Lord" had received the most airplay in the 21st century of any song released by the record label,[176] ahead of Lennon's "Imagine" and the Beatles' "Hey Jude".[177]

"My Sweet Lord" was ranked 454th on Rolling Stone's list of "the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time" in 2004[178] and 460th on the magazine's revised list in 2010.[179] It has also appeared in the following critics' best-song lists and books, among others: The 7,500 Most Important Songs of 1944–2000 by author Bruce Pollock (2005),[citation needed] Dave Thompson's 1000 Songs That Rock Your World (2011; ranked at number 247),[citation needed] Ultimate Classic Rock's "Top 100 Classic Rock Songs" (2013; number 56),[citation needed] the NME's "100 Best Songs of the 1970s" (2012; number 65),[citation needed] and the same magazine's "500 Greatest Songs of All Time" (2014; number 270).[citation needed]

Re-releases and alternative versions

Since its initial release on All Things Must Pass, "My Sweet Lord" has appeared on the 1976 compilation The Best of George Harrison and 2009's career-spanning Let It Roll: Songs by George Harrison.[180] The original UK single (with "What Is Life" as the B-side) was reissued on Christmas Eve 1976 in Britain[181] – a "provocative" move by EMI, given the publicity the lawsuit had attracted that year for the song.[182] The song appears in the 2017 Marvel Studios film Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2,[183] and it is included on the film's soundtrack.[184]

To promote the 50th anniversary reissue of All Things Must Pass in December 2021, the Harrison estate released a music video for the 2020 mix of "My Sweet Lord".[185] Executive produced by Dhani Harrison and David Zonshine, it was written and directed by Lance Bangs, and stars Mark Hamill, Vanessa Bayer and Fred Armisen as secret agents investigating a mysterious phenomenon around Los Angeles. Much of the video follows Armisen's perspective, from a room filled with books to a large cinema showing a fictional film of George Harrison's home footage, titled All Things Must Pass. The video features cameos from many celebrities – including Patton Oswalt, "Weird Al" Yankovic, Ringo Starr, Jeff Lynne, Joe Walsh, Dhani and Olivia Harrison – and ends with Armisen and Bayer's characters solving the mystery by hearing the song for the first time on their car radio.[185][186]

1975 – "The Pirate Song"

On 26 December 1975, Harrison made a guest appearance on his friend Eric Idle's BBC2 comedy show Rutland Weekend Television,[187][188] sending up his serious public image, and seemingly about to perform "My Sweet Lord".[189]

As a running gag in the show, Harrison interrupts the proceedings, hoping for an acting role as "Pirate Bob", dressed in a pirate costume with a parrot on his shoulder.[188][190] He gets turned down each time by Idle and RWT regular Neil Innes, who simply want him to play the part of "George Harrison".[191] At the end, dressed in more normal attire and backed by the house band, Harrison appears on stage strumming the introduction to "My Sweet Lord" on acoustic guitar.[192] Instead of continuing with the song, Harrison takes his chance to play Pirate Bob[187] by abruptly segueing into a sea shanty.[193] Idle, in his role as a "greasy" compère, reacts with horror[191] and attempts to have Harrison removed from the studio.[190][nb 13]

This performance is known as "The Pirate Song", co-written by Harrison and Idle,[194] and the recording is only available unofficially on bootleg compilations such as Pirate Songs.[192] Commenting on the parallels with Harrison's real-life reluctance to play the pop star, Simon Leng writes, "there was great resonance within these gags."[191]

2001 – "My Sweet Lord (2000)"

In January 2001, Harrison included a new version of the song as a bonus track on the remastered All Things Must Pass album.[6] Titled "My Sweet Lord (2000)", it features Harrison sharing vocals with Sam Brown, the daughter of his friend Joe Brown,[195] backed by mostly new instrumentation, including acoustic guitar by his son Dhani and tambourine by Ray Cooper.[196][197] The track opens with a "snippet" of sitar, in Leng's description, to "emphasize its spiritual roots".[198] Harrison said that his motivation for remaking the song was partly to "play a better slide guitar solo".[162] As further reasons, he cited the "spiritual response" that the song had long received, together with his interest in reworking the tune to avoid the contentious musical notes.[199] Of the extended slide-guitar break on "My Sweet Lord (2000)", Leng writes: "[Harrison] had never made so clear a musical statement that his signature bottleneck sound was as much his tool for self-expression as his vocal cords."[198] Elliot Huntley opines that Harrison's vocal was more "gospel inflected" and perhaps even more sincere than on the original recording, "given his deteriorating health" during the final year of his life.[197]

This version also appeared on the January 2002 posthumous release of the "My Sweet Lord" charity CD single, comprising the original "My Sweet Lord", Harrison's reworking, and the acoustic run-through of "Let It Down" (with recent overdubs, another 2001 bonus track).[200] Proceeds went to Harrison's Material World Charitable Foundation for dispersal to selected charities, apart from in the United States, where proceeds went to the Self Realization Fellowship.[201] For some months after the single release, a portion of "My Sweet Lord (2000)" looped on Harrison's official website over screen images of lotus petals scattering and re-forming.[202] It also appears on the 2014 Apple Years 1968–75 reissue of All Things Must Pass.[203]

2011 – Demo version

In November 2011, a demo of "My Sweet Lord", with Harrison backed by just Voormann and Starr,[204][205] was included on the deluxe edition CD accompanying the British DVD release of Scorsese's Living in the Material World documentary.[206] The trio recorded the song at EMI Studios on 26 May 1970, on the first of two days dedicated to taping demos of compositions under consideration for All Things Must Pass.[205][207]

Giles Martin, who helped organise Harrison's recordings archive at Friar Park for the film project, described the track as an early "live take".[208] The demo was released internationally in May 2012 on the Early Takes: Volume 1 compilation.[206][209] In his album review for Rolling Stone, David Frick deemed this version of the song an "acoustic hosanna".[210]

Harrison live versions

Harrison performed "My Sweet Lord" at every one of his relatively few solo concerts,[211] starting with the two Concert for Bangladesh shows at New York's Madison Square Garden on 1 August 1971.[212] The recording released on the subsequent live album was taken from the evening show[213] and begins with Harrison's spoken "Hare Krishna" over his opening acoustic-guitar chords.[214] Among the 24 backing musicians was a "Soul Choir" featuring singers Claudia Lennear, Dolores Hall and Joe Greene,[215] but it was Harrison who sang the end-of-song Guru Stotram prayer in his role as lead vocalist, unlike on the studio recording (where it was sung by the backing chorus).[216] The slide guitar parts were played by Eric Clapton and Jesse Ed Davis.[217]

During his 1974 North American tour, Harrison's only one there as a solo artist, he performed "My Sweet Lord" as the encore at each show.[218][nb 14] In contrast with the subtle shift from "hallelujah"s to Sanskrit chants on his 1970 original,[33] Harrison used the song to engage his audience in kirtan, the practice of "chanting the holy names of the Lord" in Indian religions – from "Om Christ!" and Krishna, to Buddha and Allah[221] – with varying degrees of success.[222][223] Backed by a band that again included Billy Preston, Harrison turned "My Sweet Lord" into an extended gospel-funk piece, closer in its arrangement to Preston's Encouraging Words version and lasting up to ten minutes.[224][nb 15]

Harrison's second and final solo tour took place in Japan in December 1991, with Clapton's band.[226][227] A live version of "My Sweet Lord" recorded at the Tokyo Dome, on 14 December, was released the following year on the Live in Japan album.[228]

Cover versions and tributes

"My Sweet Lord" attracted many cover versions in the early 1970s and was the most performed song of 1971. Its coinciding with a trend for spirituality in rock music ensured it was frequently performed on religious-themed television shows. The song was also popular among supper club performers following recordings by artists such as Johnny Mathis.[229]

The song was accepted as an authentic work in the gospel tradition;[230] in music journalist Chris Ingham's description, it became a "genuine gospel classic".[231] Many of the Christian cover artists have omitted the mantra lyrics on religious grounds.[183]

In 1972, Nina Simone released an 18-minute gospel reworking of "My Sweet Lord", performed live at Fort Dix before a group of African-American soldiers.[232] It served as an anti-Vietnam War statement and the centrepiece of her album Emergency Ward!,[49] which also included an 11-minute version of Harrison's "Isn't It a Pity".[232] Simone interspersed the song with the David Nelson poem "Today Is a Killer", giving the performance an apocalyptic ending.[232]

By the late 1970s, "My Sweet Lord" was the most covered song written and released by any of the former Beatles since the band's break-up.[233] Edwin Starr and Byron Lee and the Dragonaires were among the other artists who recorded it.[49]

In April 2002, Elton John, Sting, James Taylor, Ravi Shankar, Anoushka Shankar and others performed "My Sweet Lord" to close the Harrison-tribute opening portion of the Rock for the Rainforest benefit concert, held at Carnegie Hall in New York City.[234] At the Concert for George on 29 November 2002, it was performed by Billy Preston.[235]

On July 28, 2023, Damian “Jr. Gong” Marley released a single of his cover of “My Sweet Lord”. Marley said that he chose to cover “My Sweet Lord” because he “heard the song and liked it.” Afterwards, Marley learned that his father, Bob Marley, and George Harrison had met in 1975.

Personnel

According to Mal Evans' diary (except where noted), the following musicians played on Harrison's original version of "My Sweet Lord".[59]

- George Harrison – vocals, acoustic guitars,[54] slide guitars, backing vocals

- Eric Clapton – acoustic guitar

- Pete Ham – acoustic guitar

- Joey Molland – acoustic guitar

- Peter Frampton – acoustic guitar[51]

- Gary Brooker – piano

- Bobby Whitlock – harmonium

- Klaus Voormann – bass

- Ringo Starr – drums

- Alan White – tambourine

- uncredited – zithers[60]

- unidentified orchestral musicians – eight violins, eight violas, four cellos, two double basses[75]

- John Barham – string arrangement

Accolades

| Year | Awards | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Record World | Best Single Disc of the Year | Won[113] |

| Melody Maker | British Single of the Year | Won[125] | |

| World Single of the Year | Won[125] | ||

| 1972 | NME Awards | Best Single Disc | Won[236] |

| 14th Grammy Awards | Record of the Year | Nominated[237] | |

| 17th Ivor Novello Awards | The "A" Side of the Record Issued in 1971 Which Achieved the Highest Certified British Sales | Won[238] | |

| The Most Performed Work of the Year | Won[238] |

Chart performance

Weekly charts

|

Original release

|

Posthumous reissue

|

Year-end charts

| Chart (1971) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Singles Chart[240] | 2 |

| Austrian Singles Chart[265] | 2 |

| Canadian RPM Singles Chart[266] | 7 |

| Dutch Singles Chart[267] | 21 |

| German Singles Chart[268] | 7 |

| Japanese Oricon Singles Chart[246] | 38 |

| UK Singles Chart[269] | 1 |

| US Billboard Year-End Singles[270] | 31 |

| Chart (2002) | Position |

|---|---|

| Canadian Singles Chart[271] | 33 |

| Irish Singles Chart[272] | 89 |

| UK Singles Chart[273] | 56 |

Certifications and sales

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Italy (FIMI)[274] | Gold | 35,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[275] | 2× Platinum | 269,000[246] |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[276] | 2× Platinum | 60,000‡ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[277] | Platinum | 60,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[279] | Platinum | 960,561[278] |

| United States (RIAA)[280] | 2× Platinum | 2,000,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

- ^ The same verse appears at the end of Ravi Shankar's "Vandanaa Trayee", the opening track of the Harrison-produced 1997 album Chants of India.[37]

- ^ Hawkins' gospel group also overdubbed vocals onto the Harrison–Preston collaboration "Sing One for the Lord" at this time.[5]

- ^ Authors Simon Leng and Bruce Spizer list Preston as having played on the recording, along with Clapton, Gary Wright (on piano), Voormann, and all four members of Badfinger (on acoustic guitars and tambourine).[51][60] Wright's first Harrison session was for "Isn't It a Pity", however, which took place on 2 June.[61] Leng compiled his description of the album sessions after consulting Voormann and John Barham in the early 2000s, and from an interview with Molland; Leng states that his keyboard credits for All Things Must Pass are "more indicative than authoritative".[62] According to Kruppa, citing Evans' list, Badfinger drummer Mike Gibbins was evidently "sitting out" the session for "My Sweet Lord", having played tambourine on "Wah-Wah" earlier that day.[59]

- ^ Molland added: "I remember hearing the rough-mix playback of 'My Sweet Lord'. The balance was all there, it was so incredibly full – an enormous acoustic guitar sound without any double tracking or anything. Just all of us going at once, straight on."[63]

- ^ In his 2010 autobiography, however, Bobby Whitlock states that he sang backing vocals with Harrison.[70]

- ^ Author Ian MacDonald credited Harrison with inspiring this "Spiritual Revival", due to his championing of Indian culture and Hindu philosophy from 1966 onwards with the Beatles.[99]

- ^ Harrison said he still received such letters in the 1980s.[102]

- ^ Lennon told a reporter, "Every time I put the radio on, it's 'Oh my Lord' – I'm beginning to think there must be a God."[45]

- ^ Elliot Huntley comments: "People don't usually hear a single and then automatically go and buy an expensive boxed-set triple album on the off-chance."[142]

- ^ He commented that whenever he listened to the radio, "every tune I hear sounds like something else."[49]

- ^ Woffinden said that Harrison showed admirable restraint in declining to take legal action against the Jam or publicly comment on such a "blatant" appropriation.[136] Clayson cites Harrison's agitation at the "'He's So Fine' affair" as the reason he overlooked several other potential infringements, including Roxy Music's "A Song for Europe" (which resembled "While My Guitar Gently Weeps"), Madonna's "Material Girl" (which borrowed from "Living in the Material World"), and Enya's "Orinoco Flow" (which used Harrison's guitar motif from "Blow Away").[155]

- ^ Subsequent charges of plagiarism in the music industry have resulted in a policy of swift settlement and therefore limited damage to an artist's credibility: the Rolling Stones' "Anybody Seen My Baby?", Oasis' "Shakermaker", "Whatever" and "Step Out", and the Verve's "Bitter Sweet Symphony" are all examples of songs whose writing credits were hastily altered to acknowledge composers of a potentially plagiarised work, with the minimum of litigation.[165][166][167]

- ^ Idle supplied the nagging references to "Sugar Pie Honey Bunch" and "Rescue Me" on "This Song".[49]

- ^ At his press conference in Los Angeles before the tour, Harrison said he would be playing the song with a "slightly different" arrangement,[219] adding that, as with "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)", "It should be much more loose."[220]

- ^ The performance of the song at Tulsa's Assembly Center on 21 November marked the only guest appearance of the tour when Leon Russell joined the band on stage.[225]

References

- ^ Pitchfork Staff, "The 200 Best Songs of the 1970s", Pitchfork, 22 August 2016 (retrieved 13 October 2022).

- ^ Newport, p. 70.

- ^ Leng, pp. 71, 84.

- ^ a b c d e Clayson, George Harrison, p. 280.

- ^ a b c d Leng, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 180.

- ^ a b c John Harris, "A Quiet Storm", Mojo, July 2001, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Andy Davis, Billy Preston Encouraging Words CD, liner notes (Apple Records, 2010; produced by George Harrison & Billy Preston).

- ^ Inglis, p. 21.

- ^ a b Allison, p. 46.

- ^ Andy Davis, The Radha Krsna Temple CD, liner notes (Apple Records, 2010; produced by George Harrison; reissue produced by Andy Davis & Mike Heatley).

- ^ a b c d Badman, p. 203.

- ^ Miles, p. 362.

- ^ a b Bright Tunes Music v Harrisongs (p. 179), UC Berkeley School of Law (retrieved 17 September 2012).

- ^ a b Huntley, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Joseph C. Self, "The 'My Sweet Lord'/'He's So Fine' Plagiarism Suit", Abbeyrd's Beatles Page (retrieved 15 September 2012) Archived 8 February 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leng, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Lois Wilson, "The Fifth Element", Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970), Emap (London, 2003), p. 80.

- ^ a b c Greene, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d George Harrison, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d e f g Inglis, p. 24.

- ^ Huntley, p. 54.

- ^ Harry, p. 238.

- ^ Kahn, p. 539.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 84.

- ^ Allison, p. 6.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, p. 280.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli, p. 195.

- ^ Leng, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 267.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, "A Few Words About George", in The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c MacFarlane, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Tillery, p. 88.

- ^ Greene, p. 182.

- ^ Greene, pp. ix, 182.

- ^ Swami Atmananda (trans.), "Guru Stotram (Prayerful glorification of the Spiritual Teacher)" Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, chinmayatoronto.org (retrieved 11 September 2012).

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 428, 488.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli, p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e f Madinger & Easter, p. 428.

- ^ a b c Spizer, p. 211.

- ^ Leng, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 211, 340.

- ^ a b Clayson, George Harrison, p. 281.

- ^ a b Bruce Eder, "Billy Preston Encouraging Words", AllMusic (retrieved 13 September 2012).

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 143.

- ^ Spizer, p. 340.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 90, 91, 95, 352.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 323.

- ^ a b c d e f Jon Dennis, "Life of a Song: My Sweet Lord – the song that earned George Harrison a lawsuit", ft.com, 31 July 2018 (retrieved 23 October 2020).

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 427–34.

- ^ a b c d e f Spizer, p. 212.

- ^ Badman, p. 10.

- ^ MacFarlane, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c d Fleming & Radford, p. 18.

- ^ Fleming & Radford, pp. 6–7, 18.

- ^ Kruppa, event occurs at 13:30–13:39.

- ^ Kruppa, event occurs at 13:30–17:15.

- ^ a b John Harris, "How George Harrison Made the Greatest Beatles Solo Album of Them All", Classic Rock/loudersound.com, 27 November 2016 (retrieved 1 November 2020).

- ^ a b c Kruppa, event occurs at 19:37–20:05.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 83.

- ^ Fleming & Radford, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Leng, pp. 79fn, 82fn.

- ^ a b c David Simons, "The Unsung Beatle: George Harrison's behind-the-scenes contributions to the world's greatest band", Acoustic Guitar, February 2003, p. 60 (archived version retrieved 6 May 2021).

- ^ a b Olivia Harrison, p. 282.

- ^ Fleming & Radford, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Goldmine1, "Peter Frampton Gives His Farewell to the Road", Goldmine, 24 July 2019 (retrieved 4 July 2019).

- ^ Harry, p. 180.

- ^ Tim Jones, "Peter Frampton Still Alive!", Record Collector, April 2001, p. 83.

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 142.

- ^ Whitlock, pp. 79–80.

- ^ MacFarlane, pp. 72, 76, 79.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 279–80.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 188.

- ^ MacFarlane, p. 158.

- ^ a b Kruppa, event occurs at 31:15–31:30.

- ^ Leng, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c Pedler, pp. 621–24.

- ^ Leng, pp. 83, 84–85.

- ^ a b c Phil Spector interview, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD, 2011 (directed by Martin Scorsese; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair & Martin Scorsese).

- ^ a b c d Spizer, p. 213.

- ^ Doggett, p. 36.

- ^ Badman, p. 15.

- ^ Spizer, p. 220.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 308.

- ^ "Howard Worth discussing Raga (2010)" on YouTube (retrieved 15 February 2012).

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 62.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 93.

- ^ Badman, p. 22.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 99.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 211, 231.

- ^ a b Doggett, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Frontani, p. 158.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 142–43.

- ^ Leng, pp. 85, 105.

- ^ Tillery, p. 89.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 233.

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 40.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 294.

- ^ Ian MacDonald, "The Psychedelic Experience", Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967), Emap (London, 2002), pp. 35–36.

- ^ "George Harrison & the Art of Dying: How a lifetime of spiritual search led to a beautiful death", Beliefnet, December 2002 (retrieved 1 November 2020).

- ^ Greene, pp. 182–83.

- ^ Greene, p. 183.

- ^ Jackson, p. 28.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 332.

- ^ Badman, p. 18.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 352, 262.

- ^ Badman, p. 21.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 352.

- ^ "RPM 100 Singles, 26 December 1970" Archived 29 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 4 August 2012).

- ^ Badman, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d "Artist: George Harrison", Official Charts Company (retrieved 6 May 2013).

- ^ "Top 10 Best Selling UK Singles of 1971" Archived 14 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Pop Report (retrieved 16 September 2012).

- ^ a b c Badman, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Murrells, p. 395.

- ^ Inglis, p. 23.

- ^ a b Frontani, pp. 158, 266.

- ^ Billboard Review Panel, "Spotlight Singles", Billboard, 21 November 1970, p. 88 (retrieved 21 October 2020).

- ^ "Picks of the Week" (PDF). Record World. 28 November 1970. p. 1. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ a b Ben Gerson, "George Harrison All Things Must Pass" Archived 28 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, 21 January 1971, p. 46 (retrieved 30 March 2014).

- ^ Alan Smith, "George Harrison: All Things Must Pass (Apple)", NME, 5 December 1970, p. 2; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required; retrieved 30 March 2014).

- ^ a b Hunt, p. 32.

- ^ Frontani, p. 266.

- ^ Don Heckman, "Pop: Two and a Half Beatles on Their Own", The New York Times, 20 December 1970, p. 104 (retrieved 3 November 2020).

- ^ David Hughes, "New Singles: Sweet smell of success for George!", Disc and Music Echo, 16 January 1971, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Artist: George Harrison, UMD Music (retrieved 14 September 2012).

- ^ Badman, p. 58.

- ^ Badman, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Clayson, George Harrison, p. 354.

- ^ a b Huntley, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Clayson, George Harrison, p. 353.

- ^ Pedler, p. 624.

- ^ Badman, pp. 94, 109.

- ^ a b Huntley, p. 132.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 99, 102.

- ^ Clayson, Ringo Starr, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Woffinden, p. 102.

- ^ Badman, p. 191.

- ^ Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 420 F. Supp. 177 – Dist. Court, SD New York 1976.

- ^ a b Huntley, p. 136.

- ^ a b Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 353–54.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Huntley, p. 134.

- ^ a b David Cavanagh, "George Harrison: The Dark Horse", Uncut, August 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 355.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 47, 132.

- ^ Clayson, Ringo Starr, p. 267.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 355, 479.

- ^ Huntley, p. 147.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 132.

- ^ Inglis, p. 61.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 340.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 356.

- ^ MacFarlane, p. 103.

- ^ Woffinden, p. 99.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 354–55, 367.

- ^ Badman, p. 195.

- ^ Sheff, p. 150.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 296, 353.

- ^ Nick Deriso, "Classic Rock Artists Who (Allegedly) Ripped Somebody Off", Ultimate Classic Rock, 6 October 2017 (retried 22 October 2020).

- ^ a b Richie Unterberger, "George Harrison 'My Sweet Lord'", AllMusic (retrieved 1 April 2012).

- ^ Mark Sullivan, "'More Popular Than Jesus': The Beatles and the Religious Far Right", Popular Music, vol. 6 (3), October 1987, p. 319.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 85.

- ^ Luhrssen & Larson, p. 158.

- ^ Jordan Runtagh, "Songs on Trial: 12 Landmark Music Copyright Cases", Rolling Stone, 8 June 2016 (retrieved 21 October 2020).

- ^ Davis, p. 540.

- ^ "Vinyl Countdown: The 50 Best Oasis Songs", Q: Oasis Special Edition, May 2002, pp. 71, 74, 76.

- ^ Greg Prato, "The Verve 'Bittersweet Symphony'", AllMusic (retrieved 17 September 2012).

- ^ Oliver Sacks, "Speak, Memory", The New York Review of Books, 21 February 2013 (retrieved 23 October 2020).

- ^ Hamish Champ, The 100 Best-Selling Albums of the 70s, Amber Books (London, 2004); quoted in The Super Seventies "Classic 500", George Harrison – All Things Must Pass (retrieved 14 September 2012).

- ^ Huntley, p. 53.

- ^ Jayson Greene, "George Harrison All Things Must Pass", Pitchfork, 19 June 2016 (retrieved 21 October 2020).

- ^ Greg Kot, "All Things Must Pass", Chicago Tribune, 2 December 2001 (retrieved 3 November 2020).

- ^ Roy Trakin, "By George: Harrison's Post-Beatles Solo Career", Capitol Vaults, June 2009; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 227, 229.

- ^ Boonsri Dickinson, "10 Best George Harrison Songs", AOL Radio, 3 April 2010 (archived version retrieved 5 April 2021).

- ^ "George Harrison's My Sweet Lord Is Apple Records' Most Played Track This Century", The Irish News, 29 August 2018 (retrieved 23 October 2020).

- ^ "George Harrison 'My Sweet Lord' Is Apple's Most Played Song of the Century", Noise11, 30 August 2018 (retrieved 21 October 2020).

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time (1–500)", rollingstone.com, 9 December 2004 (archived version retrieved 16 July 2021).

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time: 460. George Harrison, 'My Sweet Lord'", rollingstone.com, 7 April 2011 (retrieved 16 July 2021).

- ^ Inglis, pp. 150, 156.

- ^ Badman, p. 199.

- ^ Carr & Tyler, p. 122.

- ^ a b Tom Breihan, "The Number Ones: George Harrison's 'My Sweet Lord'", Stereogum, 18 January 2019 (retrieved 21 October 2020).

- ^ Jack Shepard, "Tracklist for Guardians of the Galaxy's Awesome Mixtape Vol. 2 revealed", The Independent, 19 April 2017 (retrieved 27 August 2017).

- ^ a b Jon Blistein, "Ringo Starr Chucks Popcorn at Fred Armisen in Video for George Harrison's 'My Sweet Lord'", rollingstone.com, 15 December 2021 (retrieved 18 December 2021).

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord (Official Music Video)", George Harrison/YouTube, 15 December 2021 (retrieved 18 December 2021).

- ^ a b McCall, p. 47.

- ^ a b Badman, p. 172.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 370.

- ^ a b MacFarlane, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Leng, p. 189.

- ^ a b Madinger & Easter, p. 453.

- ^ Huntley, p. 129.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 314.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 446, 457.

- ^ George Harrison's liner notes, booklet accompanying All Things Must Pass reissue (Gnome Records, 2001; produced by George Harrison & Phil Spector).

- ^ a b Huntley, pp. 306–07.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 285.

- ^ Interview with Chris Carter (recorded Hollywood, CA, 15 February 2001) on A Conversation with George Harrison, Discussing the 30th Anniversary Reissue of "All Things Must Pass", Capitol Records, DPRO-7087-6-15950-2-4; event occurs between 5:28 and 7:05.

- ^ William Ruhlmann, "George Harrison 'My Sweet Lord (2002)'", AllMusic (retrieved 15 September 2012).

- ^ Harry, p. 120.

- ^ "In Memoriam: George Harrison", Abbeyrd's Beatles Page, 16 January 2002 (retrieved 15 September 2012).

- ^ Joe Marchese, "Give Me Love: George Harrison's 'Apple Years' Are Collected on New Box Set", The Second Disc, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 26 September 2014).

- ^ Terry Staunton, "Giles Martin on George Harrison's Early Takes, track-by-track", MusicRadar, 18 May 2012 (retrieved 17 February 2013).

- ^ a b Kruppa, event occurs at 11:12–11:33.

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas Erlewine, "George Harrison: Early Takes, Vol. 1", AllMusic (retrieved 15 September 2012).

- ^ Fleming & Radford, pp. 6, 10–11.

- ^ Giles Martin's liner notes, Early Takes: Volume 1 CD (UME, 2012; produced by George Harrison, Giles Martin & Olivia Harrison).

- ^ Randy Lewis, "Rare Music from George Harrison, Martin Scorsese Doc out on CD, DVD", Pop & Hiss /latimes.com, 2 May 2012 (archived version retrieved 10 September 2021).

- ^ David Fricke, "George Harrison Early Takes Volume 1", Rolling Stone, 23 May 2012 (retrieved 16 September 2012).

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 436–37, 447, 481–82.

- ^ Schaffner, p. 147.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 438.

- ^ Pieper, p. 27.

- ^ Spizer, p. 242.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 122.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 196.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 447.

- ^ Kahn, p. 184.

- ^ "'Everybody Is Very Friendly': Melody Maker, 2/11/74", Uncut Ultimate Music Guide: George Harrison, TI Media (London, 2018), p. 74.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 339.

- ^ Leng, pp. 160–65.

- ^ Greene, p. 215.

- ^ Leng, pp. 163, 172–73.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 449.

- ^ Badman, p. 471.

- ^ Lavezzoli, p. 196.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 483.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, pp. 294–95.

- ^ Clayson, George Harrison, p. 295.

- ^ Ingham, pp. 127–28.

- ^ a b c Mark Richardson, "Nina Simone Emergency Ward!", AllMusic (retrieved 16 June 2009).

- ^ Schaffner, p. 157.

- ^ Roger Friedman, "Sting Strips for Charity, Elton Puts on Pearls", foxnews.com, 15 April 2002 (archived version retrieved 19 July 2016).

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine, "Original Soundtrack: Concert for George", AllMusic (retrieved 8 August 2012).

- ^ "1972 Awards", nme.com (retrieved 19 October 2010).

- ^ "Grammy Awards 1972", awardsandshows.com (retrieved 14 September 2014).

- ^ a b "The Ivors 1972", ivorsacademy.com (retrieved 19 October 2020).

- ^ "Go-Set Australian charts – 20 February 1971" Archived 2 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, poparchives.com.au (retrieved 20 October 2020).

- ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", austriancharts.at (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", ultratop.be (retrieved 4 May 2014).

- ^ "RPM Top Singles, January 9, 1971" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 4 May 2014). Note: the double A-side single was listed only as "Isn't It a Pity" when it topped RPM's chart.

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", dutchcharts.nl (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ a b "Search the Charts". Irish Recorded Music Association. Archived from the original (enter "George Harrison" into the "Search by Artist" box, then select "Search") on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Okamoto, Satoshi (2011). Single Chart Book: Complete Edition 1968–2010 (in Japanese). Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. ISBN 978-4-87131-088-8.

- ^ "Billboard "Hits of the World"". 20 February 1971. p. 52. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", norwegiancharts.com (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "SA Charts 1969–1989, Songs M–O", South African Rock Lists, 2000 (retrieved 4 May 2014).

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Swedish Charts 1969–1972/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka" > Mars 1971 (in Swedish), hitsallertijden.nl (archived version retrieved 15 November 2013).

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", hitparade.ch (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "All Things Must Pass > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles". AllMusic (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 Singles, Week ending January 2, 1971" Archived 13 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, cashboxmagazine.com (retrieved 20 October 2020).

- ^ "Single – George Harrison, My Sweet Lord", charts.de (retrieved 3 January 2013).

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010. Mt. Martha, VIC, Australia: Moonlight Publishing.

- ^ a b "George Harrison > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles". AllMusic (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", dutchcharts.nl (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", italiancharts.com (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ ジョージ・ハリスン-リリース-ORICON STYLE-ミュージックHighest position and charting weeks of "My Sweet Lord" by George Harrison, Oricon Style (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "Norwegian charts portal", norwegiancharts.com (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "George Harrison – My Sweet Lord", swedishcharts.com (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "Schweizer Hitparade", Swiss Music Charts (retrieved 28 April 2010).

- ^ "Austriancharts.st – Jahreshitparade 1971". Hung Medien. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "RPM 100 Top Singles of '71", Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 4 May 2014).

- ^ "Dutch charts jaaroverzichten 1971" (ASP) (in Dutch). Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Top 100 Single-Jahrescharts" (in German). Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Dan Lane, "The biggest selling singles of every year revealed! (1952–2011)", Official Charts Company, 18 November 2012 (retrieved 4 May 2014).

- ^ "Top Pop 100 Singles", Billboard, 25 December 1971, p. 11 (retrieved 4 May 2014).

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Singles of 2002". Jam!. 14 January 2003. Archived from the original on 6 September 2004. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Songs of 2002". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 2002. Archived from the original on 2 June 2004. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "The Official UK Singles Chart 2002" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – George Harrison – My Sweet Lord" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Tatsaku, Ren (2011). Oricon Sales Report (in Japanese). Tokyo: Oricon Style.

- ^ "New Zealand single certifications – George Harrison – My Sweet Lord". Radioscope. Retrieved 18 December 2024. Type My Sweet Lord in the "Search:" field.

- ^ "Spanish single certifications – George Harrison – My Sweet Lord". El portal de Música. Productores de Música de España. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (19 September 2017). "The UK's Official Chart 'millionaires' revealed". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "British single certifications – George Harrison – My Sweet Lord". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "American single certifications – George Harrison – My Sweet Lord". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

Sources

- Dale C. Allison Jr, The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Roy Carr & Tony Tyler, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Trewin Copplestone Publishing (London, 1978; ISBN 0-450-04170-0).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Alan Clayson, Ringo Starr, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-488-5).

- Stephen Davis, Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones, Broadway Books (New York, NY, 2001; ISBN 0-7679-0312-9).

- Peter Doggett, "The Apple Years", Record Collector, April 2001, pp. 34–40.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, Harrison, Rolling Stone Press/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0-7432-3581-9).

- Don Fleming & Richard Radford, Archival Notes – the Making of All Things Must Pass, Capitol Records/Calderstone Productions (Los Angeles, CA/London, 2021).

- Michael Frontani, "The Solo Years", in Kenneth Womack (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-139-82806-2), pp. 153–82.

- Joshua M. Greene, Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken, NJ, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3).

- George Harrison, I Me Mine, Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA, 2002 [1980]; ISBN 0-8118-3793-9).

- Olivia Harrison, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Abrams (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4).

- Bill Harry, The George Harrison Encyclopedia, Virgin Books (London, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0).

- Chris Hunt (ed.), NME Originals: Beatles – The Solo Years 1970–1980, IPC Ignite! (London, 2005).

- Elliot J. Huntley, Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles, Guernica Editions (Toronto, ON, 2006; ISBN 1-55071-197-0).