Tucana

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Tuc[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Tucanae |

| Pronunciation | /tjuːˈkeɪnə/, genitive /-ni/ |

| Symbolism | the toucan |

| Right ascension | 22h 08.45m to 01h 24.82m [2] |

| Declination | −56.31° to −75.35°[2] |

| Quadrant | SQ1 |

| Area | 295 sq. deg. (48th) |

| Main stars | 3 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 17 |

| Stars with planets | 5 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 1 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 2[note 1] |

| Brightest star | α Tuc (2.87m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Bordering constellations | Grus Indus Octans Hydrus Eridanus (corner) Phoenix |

| Visible at latitudes between +25° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of November. | |

Tucana (The Toucan) is a constellation in the southern sky, named after the toucan, a South American bird. It is one of twelve constellations conceived in the late sixteenth century by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Tucana first appeared on a 35-centimetre-diameter (14 in) celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius and was depicted in Johann Bayer's star atlas Uranometria of 1603. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille gave its stars Bayer designations in 1756. The constellations Tucana, Grus, Phoenix and Pavo are collectively known as the "Southern Birds".

Tucana is not a prominent constellation as all of its stars are third magnitude or fainter; the brightest is Alpha Tucanae with an apparent visual magnitude of 2.87. Beta Tucanae is a star system with six member stars, while Kappa is a quadruple system. The constellation contains 47 Tucanae, one of the brightest globular clusters in the sky, and most of the Small Magellanic Cloud.

History

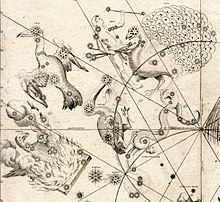

Tucana is one of the twelve constellations established by the astronomer Petrus Plancius from the observations of the southern sky by the Dutch explorers Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman, who had sailed on the first Dutch trading expedition, known as the Eerste Schipvaart, to the East Indies. It first appeared on a 35-centimetre-diameter (14 in) celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius with Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in the German cartographer Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. Both Plancius and Bayer depict it as a toucan.[3][4] De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue the same year under the Dutch name Den Indiaenschen Exster, op Indies Lang ghenaemt "the Indian magpie, named Lang in the Indies",[5] by this meaning a particular bird with a long beak—a hornbill, a bird native to the East Indies. A 1603 celestial globe by Willem Blaeu depicts it with a casque.[6] It was interpreted on Chinese charts as Niǎohuì "bird's beak", and in England as "Brasilian Pye", while Johannes Kepler and Giovanni Battista Riccioli termed it Anser Americanus "American Goose", and Caesius as Pica Indica.[7] Tucana and the nearby constellations Phoenix, Grus and Pavo are collectively called the "Southern Birds".[8]

Characteristics

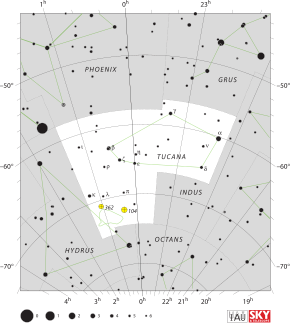

Irregular in shape, Tucana is bordered by Hydrus to the east, Grus and Phoenix to the north, Indus to the west and Octans to the south. Covering 295 square degrees, it ranks 48th of the 88 constellations in size. The recommended three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Tuc".[1] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 10 segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 22h 08.45m and 01h 24.82m , while the declination coordinates are between −56.31° and −75.35°.[2] As one of the deep southern constellations, it remains below the horizon at latitudes north of the 30th parallel in the Northern Hemisphere, and is circumpolar at latitudes south of the 50th parallel in the Southern Hemisphere.[9]

Features

Stars

Although he depicted Tucana on his chart, Bayer did not assign its stars Bayer designations. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille labelled them Alpha to Rho in 1756, but omitted Omicron and Xi, and labelled a pair of stars close together Lambda Tucanae, and a group of three stars Beta Tucanae. In 1879, American astronomer Benjamin Gould designated a star Xi Tucanae—this had not been given a designation by Lacaille who had recognized it as nebulous, and it is now known as the globular cluster 47 Tucanae. Mu Tucanae was dropped by Francis Baily, who felt the star was too faint to warrant a designation, and Kappa's two components came to be known as Kappa1 and Kappa2.[11]

The layout of the brighter stars of Tucana has been likened to a kite.[12] Within the constellation's boundaries are around 80 stars brighter than an apparent magnitude of 7.[13] At an apparent magnitude of 2.86,[14] Alpha Tucanae is the brightest star in the constellation and marks the toucan's head.[9] It is an orange subgiant of spectral type K3III around 199 light-years distant from the Solar System.[14] A cool star with a surface temperature of 4300 K, it is 424 times as luminous as the Sun and 37 times its diameter. It is 2.5 to 3 times as massive.[15] Alpha Tucanae is a spectroscopic binary, which means that the two stars have not been individually resolved using a telescope, but the presence of the companion has been inferred from measuring changes in the spectrum of the primary. The orbital period of the binary system is 4197.7 days (11.5 years).[16] Nothing is known about the companion.[15] Two degrees southeast of Alpha is the red-hued Nu Tucanae,[9] of spectral type M4III and lying around 290 light-years distant.[17] It is classified as a semiregular variable star and its brightness varies from magnitude +4.75 to +4.93.[18] Described by Richard Hinckley Allen as bluish,[7] Gamma Tucanae is a yellow-white sequence star of spectral type F4V and an apparent magnitude of 4.00 located around 75 light-years from Earth.[19] It also marks the toucan's beak.[20]

Beta, Delta and Kappa are multiple star systems containing six, two and four stars respectively. Located near the tail of the toucan,[9] Beta Tucanae's two brightest components, Beta1 and Beta2 are separated by an angle of 27 arcseconds and have apparent magnitudes of 4.4 and 4.5 respectively. They can be separated in small telescopes. A third star, Beta3 Tucanae, is separated by 10 arcminutes from the two, and able to be seen as a separate star with the unaided eye. Each star is itself a binary star, making six in total.[21] Lying in the southwestern corner of the constellation around 251 light-years away from Earth, Delta Tucanae consists of a blue-white primary contrasting with a yellowish companion.[12] Delta Tucanae A is a main sequence star of spectral type B9.5V and an apparent magnitude of 4.49.[22] The companion has an apparent magnitude of 9.3.[23] The Kappa Tucanae system shines with a combined apparent magnitude of 4.25, and is located around 68 light-years from the Solar System.[24] The brighter component is a yellowish star,[21] known as Kappa Tucanae A with an apparent magnitude of 5.33 and spectral type F6V,[25] while the fainter lies 5 arcseconds to the northwest.[21] Known as Kappa Tucanae B, it has an apparent magnitude of 7.58 and spectral type K1V.[26] Five arcminutes to the northwest is a fainter star of apparent magnitude 7.24—actually a pair of orange main sequence stars of spectral types K2V and K3V,[27] which can be seen individually as stars one arcsecond apart with a telescope such as a Dobsonian with high power.[21]

Lambda Tucanae is an optical double—that is, the name is given to two stars (Lambda1 and Lambda2) which appear close together from the Earth, but are in fact far apart in space. Lambda1 is itself a binary star, with two components—a yellow-white star of spectral type F7IV-V and an apparent magnitude of 6.22,[28] and a yellow main sequence star of spectral type G1V and an apparent magnitude of 7.28.[29] The system is 186 light-years distant.[28] Lambda2 is an orange subgiant of spectral type K2III that is expanding and cooling and has left the main sequence. Of apparent magnitude 5.46, it is approximately 220 light-years distant from Earth.[30]

Epsilon Tucanae traditionally marks the toucan's left leg.[20] A B-type subgiant, it has a spectral type B9IV and an apparent magnitude of 4.49. It is approximately 373 light-years from Earth.[31] It is around four times as massive as the Sun.[32]

Theta Tucanae is a white A-type star around 423 light-years distant from Earth,[33] which is actually a close binary system. The main star is classified as a Delta Scuti variable—a class of short period (six hours at most) pulsating stars that have been used as standard candles and as subjects to study asteroseismology.[34] It is around double the Sun's mass, having siphoned off one whole solar mass from its companion, now a hydrogen-depleted dwarf star of around only 0.2 solar masses.[35] The system shines with a combined light that varies between magnitudes 6.06 to 6.15 every 70 to 80 minutes.[36][37]

Zeta Tucanae is a yellow-white main sequence star of spectral type F9.5V and an apparent magnitude of 4.20 located 28 light-years away from the Solar System.[38] Despite having a slightly lower mass, this star is more luminous than the Sun.[39] The composition and mass of this star are very similar to the Sun, with a slightly lower mass and an estimated age of three billion years. The solar-like qualities make it a target of interest for investigating the possible existence of a life-bearing planet.[40] It appears to have a debris disk orbiting it at a minimum radius of 2.3 astronomical units.[41] As of 2009, no planet has been discovered in orbit around this star.[42]

Five star systems have been found to have planets, four of which have been discovered by the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) in Chile. HD 4308 is a star with around 83% of the Sun's mass located 72 light-years away with a super-Earth planet with an orbital period of around 15 days.[43] HD 215497 is an orange star of spectral type K3V around 142 light-years distant. It is orbited by a hot super-Earth every 3 days and a second planet around the size of Saturn with a period of around 567 days.[44] HD 221287 has a spectral type of F7V and lies 173 light-years away, and has a super-Jovian planet.[45] HD 7199 has spectral type KOIV/V and is located 117 light-years away. It has a planet with around 30% the mass of Jupiter that has an orbital period of 615 days.[46] HD 219077 has a planet around 10 times as massive as Jupiter in a highly eccentric orbit.[47]

Deep-sky objects

The second-brightest globular cluster in the sky after Omega Centauri, 47 Tucanae (NGC 104) lies just west of the Small Magellanic Cloud. Only 14,700 light-years distant from Earth, it is thought to be around 12 billion years old.[13] Mostly composed of old, yellow stars, it does possess a contingent of blue stragglers, hot stars that are hypothesized to form from binary star mergers.[48] 47 Tucanae has an apparent magnitude of 3.9, meaning that it is visible to the naked eye; it is a Shapley class III cluster, which means that it has a clearly defined nucleus. Near to 47 Tucana on the sky, and often seen in wide-field photographs showing it, are two much more distant globular clusters associated with the SMC: NGC 121, 10 arcminutes away from the bigger cluster's edge, and Lindsay 8.[49]

NGC 362 is another globular cluster in Tucana with an apparent magnitude of 6.4, 27,700 light-years from Earth. Like neighboring 47 Tucanae, NGC 362 is a Shapley class III cluster and among the brightest globular clusters in the sky. Unusually for a globular cluster, its orbit takes it very close to the center of the Milky Way—approximately 3,000 light-years. It was discovered in the 1820s by James Dunlop.[50] Its stars become visible at 180x magnification through a telescope.[12]

Located at the southern end of Tucana, the Small Magellanic Cloud is a dwarf galaxy that is one of the nearest neighbors to the Milky Way galaxy at a distance of 210,000 light-years. Though it probably formed as a disk shape, tidal forces from the Milky Way have distorted it. Along with the Large Magellanic Cloud, it lies within the Magellanic Stream, a cloud of gas that connects the two galaxies.[48] NGC 346 is a star-forming region located in the Small Magellanic Cloud. It has an apparent magnitude of 10.3.[12] Within it lies the triple star system HD 5980, each of its members among the most luminous stars known.[52]

The Tucana Dwarf galaxy, which was discovered in 1990, is a dwarf spheroidal galaxy of type dE5 that is an isolated member of the Local Group.[54] It is located 870 kiloparsecs (2,800 kly) from the Solar System and around 1,100 kiloparsecs (3,600 kly) from the barycentre of the Local Group—the second most remote of all member galaxies after the Sagittarius Dwarf Irregular Galaxy.[55]

The barred spiral galaxy NGC 7408 is located 3 degrees northwest of Delta Tucanae, and was initially mistaken for a planetary nebula.[12]

In 1998, part of the constellation was the subject of a two-week observation program by the Hubble Space Telescope, which resulted in the Hubble Deep Field South.[56] The potential area to be covered needed to be at the poles of the telescope's orbit for continuous observing, with the final choice resting upon the discovery of a quasar, QSO J2233-606, in the field.[57]

See also

Notes

- ^ These are Zeta Tucanae and LHS 1208.

References

- ^ a b Russell, Henry Norris (October 1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469–71. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ a b c "Tucana, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Bayer's Southern Star Chart". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Sawyer Hogg, Helen (1951). "Out of Old Books (Pieter Dircksz Keijser, Delineator of the Southern Constellations)". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 45: 215. Bibcode:1951JRASC..45..215S.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Tucana– the Toucan". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b Allen, Richard Hinckley (1963) [1899]. Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc. pp. 417–18. ISBN 0-486-21079-0.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (2000). Exploring the Night Sky with Binoculars. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-521-79390-2.

- ^ a b c d Motz, Lloyd; Nathanson, Carol (1991). The Constellations: An Enthusiast's Guide to the Night Sky. London, United Kingdom: Aurum Press. pp. 385, 389. ISBN 978-1-85410-088-7.

- ^ "Sidekick or star of the show?". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, VA: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 305–07. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ^ a b c d e Streicher, Magda (2005). "Deepsky Delights". Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of Southern Africa. 64 (9–10): 172–74. Bibcode:2005MNSSA..64..172S.

- ^ a b O'Meara, Stephen James (2013). Deep-Sky Companions: Southern Gems. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-1-107-01501-2.

- ^ a b "Alpha Tucanae". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b Kaler, Jim. "Alpha Tucanae". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Pourbaix, D.; Tokovinin, A.A.; Batten, A.H.; Fekel, F.C.; Hartkopf, W.I.; Levato, H.; et al. (2004). "SB9: The Ninth Catalogue of Spectroscopic Binary Orbits". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 424 (2): 727–732. arXiv:astro-ph/0406573. Bibcode:2004A&A...424..727P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041213. S2CID 119387088.

- ^ "Nu Tucanae – Pulsating Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (25 August 2009). "Nu Tucanae". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Gamma Tucanae". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ a b Knobel, Edward B. (1917). "On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77 (5): 414–32 [430]. Bibcode:1917MNRAS..77..414K. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.5.414.

- ^ a b c d Consolmagno, Guy (2011). Turn Left at Orion: Hundreds of Night Sky Objects to See in a Home Telescope – and How to Find Them. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-139-50373-0.

- ^ "Delta Tucanae – Star in Double System". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "CPD-65 4044B – Star in Double System". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "Kappa Tucanae – Double or Multiple Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "Kappa Tucanae A – Star in Double System". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "Kappa Tucanae B – Star in Double System". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "GJ 55.1 – Double or multiple star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ a b "HR 252 – Star in Double System". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "HD 5208 – Star in Double System". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Lambda 2 Tucanae – Red Giant Branch Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Epsilon Tucanae – Be Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Levenhagen, R. S.; Leister, N. V. (2006). "Spectroscopic Analysis of Southern B and Be Stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 371 (1): 252–62. arXiv:astro-ph/0606149. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.371..252L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10655.x. S2CID 16492030.

- ^ "Theta Tucanae – Variable Star of Delta Scuti type". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Templeton, Matthew (16 July 2010). "Delta Scuti and the Delta Scuti Variables". Variable Star of the Season. AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers). Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Templeton, Matthew R.; Bradley, Paul A.; Guzik, Joyce A. (2000). "Asteroseismology of the Multiply Periodic Delta Scuti Star Theta Tucanae". The Astrophysical Journal. 528 (2): 979–88. Bibcode:2000ApJ...528..979T. doi:10.1086/308191.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "Theta Tucanae". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Stobie, R. S.; Shobbrook, R. R. (1976). "Frequency Analysis of the Delta Scuti star, Theta Tucanae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 174 (2): 401–09. Bibcode:1976MNRAS.174..401S. doi:10.1093/mnras/174.2.401.

- ^ "Zeta Tucanae". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Santos, N. C.; Israelian, G.; Mayor, M. (July 2001). "The metal-rich nature of stars with planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 373 (3): 1019–1031. arXiv:astro-ph/0105216. Bibcode:2001A&A...373.1019S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010648. S2CID 119347084.

- ^ Porto de Mello, Gustavo; del Peloso, Eduardo F.; Ghezzi, Luan (2006). "Astrobiologically Interesting Stars Within 10 Parsecs of the Sun". Astrobiology. 6 (2): 308–331. arXiv:astro-ph/0511180. Bibcode:2006AsBio...6..308P. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.6.308. PMID 16689649. S2CID 119459291.

- ^ Trilling, D.E.; Bryden, G.; Beichman, C.A.; Rieke, G.H.; Su, K.Y.L.; Stansberry, J.A.; et al. (2008). "Debris Disks around Sun-like Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 674 (2): 1086–1105. arXiv:0710.5498. Bibcode:2008ApJ...674.1086T. doi:10.1086/525514. S2CID 54940779.

- ^ Kóspál, Ágnes; Ardila, David R.; Moór, Attila; Ábrahám, Péter (August 2009). "On the Relationship Between Debris Disks and Planets". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 700 (2): L73–L77. arXiv:0907.0028. Bibcode:2009ApJ...700L..73K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/700/2/L73. S2CID 16636256.

- ^ Udry, S.; Mayor, M.; Benz, W.; Bertaux, J.-L.; Bouchy, F.; Lovis, C.; et al. (2006). "The HARPS Search for Southern Extra-solar Planets V. A 14 Earth-masses planet orbiting HD 4308". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 447 (1): 361–67. arXiv:astro-ph/0510354. Bibcode:2006A&A...447..361U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20054084. S2CID 119078261.

- ^ Lo Curto, G.; Mayor, M.; Benz, W.; Bouchy, F.; Lovis, C.; Moutou, C.; et al. (2015). "The HARPS Search for Southern Extra-solar Planets XXII. Multiple Planet Systems from the HARPS Volume Limited Sample". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 512: A48. arXiv:1411.7048. Bibcode:2010A&A...512A..48L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913523.

- ^ Naef, D.; Mayor, M.; Benz, W.; Bouchy, F.; Lo Curto, G.; Lovis, C.; et al. (2007). "The HARPS Search for Southern Extra-solar Planets IX. Exoplanets Orbiting HD 100777, HD 190647, and HD 221287". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 470 (2): 721–26. arXiv:0704.0917. Bibcode:2007A&A...470..721N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077361. S2CID 119585936. (web preprint)

- ^ Dumusque, X.; Lovis, C.; Ségransan, D.; Mayor, M.; Udry, S.; Benz, W.; et al. (2011). "The HARPS Search for Southern Extra-solar Planets. XXX. Planetary Systems around Stars with Solar-like Magnetic Cycles and Short-term Activity Variation". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 535: A55–A66. arXiv:1107.1748. Bibcode:2011A&A...535A..55D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117148. S2CID 119192207. Archived from the original on 2015-05-29. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ Marmier, Maxime; Ségransan, D.; Udry, S.; Mayor, M.; Pepe, F.; Queloz, D.; et al. (2013). "The CORALIE Survey for Southern Extrasolar Planets XVII. New and Updated Long Period and Massive Planets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 551: A90–A103. arXiv:1211.6444. Bibcode:2013A&A...551A..90M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219639. S2CID 59467665.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- ^ Levy 2005, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Levy 2005, p. 165.

- ^ "The oldest cluster in its cloud". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Georgiev, L.; Koenigsberger, G.; Hillier, D. J.; Morrell, N.; Barbá, R.; Gamen, R. (2011). "Wind Structure and Luminosity Variations in the Wolf-Rayet/luminous Blue Variable Hd 5980". The Astronomical Journal. 142 (6): 191. Bibcode:2011AJ....142..191G. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/142/6/191. hdl:11336/9695.

- ^ "The Toucan and the cluster". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Lavery, Russell J.; Mighell, Kenneth J. (January 1992). "A New Member of the Local Group – The Tucana Dwarf Galaxy". The Astronomical Journal. 103 (1): 81–84. Bibcode:1992AJ....103...81L. doi:10.1086/116042.

- ^ van den Bergh, Sidney (2000). "Updated Information on the Local Group". The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 112 (770): 529–36. arXiv:astro-ph/0001040. Bibcode:2000PASP..112..529V. doi:10.1086/316548. S2CID 1805423.

- ^ Cristiani, S.; D'Odorico, V. (2000). "High-Resolution Spectroscopy from 3050 to 10000 Å of the Hubble Deep Field South QSO J2233-606 with UVES at the ESO Very Large Telescope". The Astronomical Journal. 120 (4): 1648–53. arXiv:astro-ph/0006128. Bibcode:2000AJ....120.1648C. doi:10.1086/301575. S2CID 117552533.

- ^ Williams, Robert E.; Baum, Stefi; Bergeron, Louis E.; Bernstein, Nicholas; Blacker, Brett S.; Boyle, Brian J.; et al. (2000). "The Hubble Deep Field South: Formulation of the Observing Campaign". The Astronomical Journal. 120 (6): 2735–46. Bibcode:2000AJ....120.2735W. doi:10.1086/316854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Cited texts

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.