Montreal and Southern Counties Railway

| Montreal & Southern Counties Railway Company | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Logo of the Montreal & Southern Counties Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

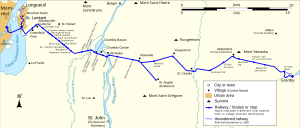

Route map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Montreal, South Shore, Granby | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit type | Interurban streetcar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of lines | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of stations | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Annual ridership | Suburban 1,772,451; Interurban 331,202; Total 2,103,653 (1936)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Headquarters | Tramways Building, Montreal, Quebec | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Began operation | November 1, 1909[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ended operation | October 13, 1956 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Canadian National Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of vehicles | 86 (1937)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 600 V DC trolley wire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Montreal and Southern Counties Railway Company (often abbreviated M&SCRC or M&SC) was an electric interurban streetcar line that served communities between Montreal and Granby from 1909 until 1956. A second branch served the city of Longueuil. Operated by the Canadian National Railway (CN), the M&SCRC ran trams on tracks in the street in Montreal and closer South Shore communities, and on separate right of way in rural areas.

History

Founding and Initial Service

The Montreal and Southern Counties Railway Company was established through an act of Canadian Parliament on June 29, 1897, with a mandate to "lay out, construct and operate, by electricity or any other mechanical power except steam, a railway [...] from a point in or near the northern limit of the county of Chambly [...] to a point in or near the city of Sherbrooke."[4]

In 1905, a bus company running from Montreal to St. Lambert was failing. After amending the company charter, M&SC "was empowered to take [over the bus company] and replace it with an electric railway."[5]

It took years to fight opposition to the laying of tracks from the Montreal Street Railway[6] and to negotiate access to the downstream shoulder of the Victoria Jubilee Bridge with the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR). GTR purchased a controlling interest in the company in exchange for a "generous infusion of money to get construction."[7]

In spring 1909, M&SC laid tracks along Riverside, Mill, Common, Grey Nun and Youville Streets in Montreal.[8] By end of October, tracks were laid all the way to St. Lambert City Hall. A celebration was held October 31, and official service began on November 1.[9]

Expansion

May 28, 1910, service was extended to Montreal South (now a part of Vieux-Longueuil at the foot of the Jacques-Cartier Bridge) and to the city of Longueuil (which at that time covered the Old Longueuil Heritage Site[10]).

In 1911 a southern branch was built from the foot of the Victoria bridge, to link St. Lambert to the Ranelagh Country Club and opened on Labour Day "to accommodate golfers." That branch was then continued east through Greenfield Park and Mackayville, junctioning with the GTR main line to St. Hyacinthe. Service to these communities started on November 1, 1912.[11]

In 1913 work began to electrify the Central Vermont Railway line between the GTR junction northeast of Mackayville and Marieville. Interurban service expanded rapidly along this existing track:[12]

- June 6, 1913: Service opened all the way to Richelieu.

- September 28, 1913: Service expanded to Marieville.

- May 3, 1914: Opening of service on new track to St. Césaire.

The Company came to a ten-year agreement with town of Granby to run trains on its Main Street (now rue Principale). In 1915 and 1916 new tracks were laid from St. Césaire to Granby. Service to Abbotsford and Granby finally opened on April 30, 1916, with a workshop at the corner of Main and Pie-IX Boulevard.[13][14]

On June 1, 1926 there was a new spur opened between Marieville and Ste. Angèle, after electrifying a rail line previously abandoned by Central Vermont.[15]

There were reports in 1915 of further expansion plans—from Longueuil to Boucherville; from Richelieu to Sorel; and from the Country Club to La Prairie.[16] None of these materialized. Neither was service ever extended from Granby to Sherbrooke as was its original mandate.[17]

The creation of the railway coincided with an increase in population in the areas serviced. According to the Census, communities along the railway in Chambly County grew 36% between 1911 and 1921 censuses; Granby city and surrounding township grew by 35% in the same period, while communities in Rouville County grew by 8%.[18]

Decline

The streetcar was moved out of the city centre of Granby in 1925. Residents and business in Granby complained about the company's operations down its main street. In winter, the streetcar snow plow would leave snow banks that impeded other traffic. A bypass to the CN station in Granby was built and the original Main Street track was discontinued.[19]

By 1928 annual ridership was up to 3.5 m passengers, and the company moved 152 metric tonnes of freight.[20] During the Great Depression, however, ridership fell by 1 million from its peak, and revenue for the company was halved.[21]

Service to Longueuil was cut in 1931. A first spur in Longueuil that led to the wharf used by the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company was abandoned in 1915.[22] In 1926, the St. Charles Street portion of the Longueuil line stopped being used.[23] Ultimately service to Longueuil was cut altogether in April 1931,[24] coinciding with the opening of the new Harbour Bridge. At that same time, the Montreal Tramways Company began offering bus service to Longueuil over the new bridge.[25] (Streetcar tracks were laid on the bridge but never used.)[26] A loop for the streetcars to turn around was installed at the corner of Ste. Hélène and Lafayette Streets in Montreal South, near the foot of the bridge, and became the new end of the line.[27]

Throughout the 1930s the railway lost money, but its importance as a means of transportation during the war years ensured that the company remained a going concern.[28] After the war in 1946, ridership peaked at 5,732,000 annual passengers, primarily on its suburban service.[29] From then on, as car ownership and the regional road network grew, ridership steadily declined.

Some time before 1937, the spur leading to Ranelagh Golf Club is abandoned.[30]

Financial Difficulties and End of Service

From 1916 to 1955, the company only ever covered its annual bond interest once. After-tax operating deficits between 1931 and 1955 totalled $5 million.[31] The parent company, Grand Trunk, struggled from its own financial difficulties and was ultimately nationalized into Canadian National Railway in 1923. Montreal & Southern Counties continued to operate under the CN Electric Railways division.[32]

On November 11, 1951, CN began cutting back its rail service in rural Southeastern Quebec. M&SC stopped electric operation beyond Marieville. CN replaced the service with three daily diesel-powered trains from Waterloo through Granby and Marieville, along the former railway's track until the junction to the St. Hyacinthe subdivision where it would go directly to Montreal's Central Station.[33] This change coincided with the end of passenger service between Waterloo and Montreal through Granby, Farnham and Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.[34]

In 1952, Greenfield Park officials were told that service would soon end.[35] Service over the Victoria Bridge between St. Lambert and Montreal was stopped on June 15, 1955 as part of the Saint Lawrence Seaway construction. The downstream shoulder was opened to car traffic.[36]

Finally, all operations of the Montreal and Southern Counties Railway ended on October 13, 1956.[37]

Service

Service to Montreal

The Montreal McGill Street Terminal was situated at the south-west corner of McGill Street and Rue Marguerite-d'Youville.

Street cars would run on a track set up along the downstream side of the Victoria Bridge where today street traffic runs.

Suburban tramways

At the South Shore terminus of the Victoria Bridge, at a station called East End, trains would go in one of two directions to provide suburban service:

- Montreal South/Longueuil: One branch would follow the bottom of CN main line embankment to Elm Street. This location hosted M&SCRC's car houses, offices, and a station. The track would then continue up Elm, Webster, Mercille and Desaulniers in St-Lambert toward Lafayette.[38] It would continue to Montreal-Sud and Longueuil.

- Greenfield Park/Mackayville: A second branch went up Churchill St. in Greenfield Park and Edward Blvd. in Mackayville (now Édouard Boulevard in the borough of St-Hubert).

Suburban streetcars ran every twenty minutes.[39]

Interurban service

Interurban trains took the same tracks as the suburban streetcars, up the Greenfield Park/Mackayville branch up to a right of way operated by Vermont Central Railway. From there, it continued past Mackayville through the modern-day borough of Saint-Hubert and the cities of Carignan, Chambly, Richelieu, Marieville, Rougement, Saint-Paul-d'Abbotsford to Granby, with a spur leaving Marieville servicing Sainte-Angèle-de-Monnoir.

Five to six interurban trains ran in each direction per day between Montreal and Granby. More stopped at Marieville, and a few ended at Ste. Angele. Interurban trains often had three cars.[40]

Freight

Freight traffic was never significant compared to other intercity services in Canada.[41] Instead of rolling down urban streets, and to avoid the weight limits on the shoulder of the Victoria Bridge, freight trains could connect to the rest of the Canadian National Railway network at a junction in Southwark rail yards (along today's Route 116 between Vieux-Longueuil and Saint-Hubert).

Infrastructure and equipment

Electrical

The railroad was "the first direct current line in Canada to use catenary construction."[42] The catenary carried 600 Volts in its suspended wire, hung on cedar polls 11 metres (36 ft) high[43] and spaced every 110 to 150 feet (33.5 to 45.7 m) on tangents and 90 to 100 feet (27.4 to 30.5 m) on curves.[44]

Electrical power was provided by Montreal Light, Heat & Power from a dam on the Richelieu River between Chambly and Richelieu. Substations were located in St. Lambert, Chambly, Rougemont and Granby.[45]

Rolling stock

In April 1911 the rolling stock of the railway consisted of eight passenger cars built by the Ottawa Car Co., two passenger and baggage cars, two trailer cars, one flat car, one sweeper car and one snow plow. All cars except the snow plow and trailers had electric drive motors.

By 1937 the rolling stock counted 13 suburban passenger cars, 2 combine motor cars, 3 suburban trailer cars, 4 express cars, 11 interurban passenger cars, 6 interurban trailers, 4 milk cars, as well as a number of special service cars, work cars and locomotives.

The main manufacturers of these railcars were National Steel Car, Ottawa Car Company and the railway's parent company, Grand Trunk.[46]

Because of its use of the side decks of the Victoria Bridge, streetcars were limited to a weight of 65,000 lb (29,500 kg) per wagon.[47]

Stations and stops

- The McGill Street Terminal, c. 1910–1920

- East Greenfield Station

- "Dogpatch" shelter at Brentwood stop

| Station or stop name[48] | Mile post[49] | Opened | Closed | Location and description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal McGill Street Terminal | 0.0 | 1909 | 1955 | Terminal building located on the southwest corner of McGill and Youville.

Interurban trains would stop in a yard behind the building, between Youville and Common (rue de la Commune) streets. Suburban cars would circle on Grey Nuns (rue des Soeurs-Grises), Youville and McGill streets.[50] |

| East End | 2.8 | 1909 | 1956 | Also called Front Street Junction, Front Street St. Lambert, East End Junction

Located at the bottom of the embankment at the foot of the Victoria Bridge. Station included a waiting room and platform. From this location, trains would take either the branch toward Montreal South-Longueuil or toward Greenfield Park–Mackayville–Granby. |

| St. Lambert | 3.1 | 1909 | 1956 | A building at the corner of Elm and St. Denis Streets.[51] |

| Montreal South | 4.9 | 1910 | 1956 | |

| Longueuil | 7.1 | 1910 | 1931 | |

| Ranelagh | 5 | 1911 | ? | Stop for the Montreal Country Club. |

| Greenfield Park | 4.6 | 1912 | 1956 | Stop at the corner of Churchill Avenue and Springfield Streets, in front of today's borough hall. |

| Mackayville | 5.2 | 1912 | 1956 | Also called Cote Noir Road.

Located at the corner of Edward Boulevard and Grande-Allée. |

| Sunlight City | 7.1 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| Croydon | 8.0 | 1913 | 1956 | Also called St. Hubert Road |

| Springfield Park | 8.3 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| Castle Gardens | 8.8 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| East Greenfield | 9.5 | 1913 | 1956 | Flag stop, also indicated as Pinehurst & East Greenfield.

Station building also served as a school house from 1916 to 1920.[52] |

| Brentwood | 10.0 | 1913 | 1956 | Flag stop with a single shed serving as a shelter for passengers waiting for the train.[53] |

| Maricourt | 10.7 | ? | ? | |

| Brookline | 11.0 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| St. Lambert Gardens | 11.4 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| Woodbine | 11.7 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| Highland Gardens | 12.3 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| Albani | 14.0 | 1913 | 1956 | Flag stop, corresponds to Albani Street in present-day Carignan, named after opera sensation Emma Albani. |

| Montreal River Road | 15.0 | 1913 | 1956 | Flag stop, corresponds to today's Bellerive Road in present-day Carignan. Named after the old name of the L'Acadie River. |

| De Salaberry Park | 15.4 | 1913 | 1956 | Flag stop, today at Parc du sentier transcanadien (Trans-Canada Trail Park) along Brassard Boulevard in Chambly. |

| Chambly | 15.9 | 1913 | 1956 | Also known as Chambly Basin. A train station that stood at the corner of Périgny Boulevard and De Salaberry Avenue. |

| Lajeunesse | 16.4 | 19?? | 1956 | A flag stop that corresponds to the corner of Périgny and Fréchette in present-day Chambly. |

| Fort Chambly | 17.2 | 1913 | 1956 | Also known as Chambly Canton |

| Bennett | 17.8 | 1913 | 1956 | Flag stop, behind the Bennett cardboard factory in southern Chambly, just before crossing the Richelieu River. |

| Richelieu | 18.1 | 1913 | 1956 | Presently a park named Parc de la gare (Train station park) sits where the station once stood.[54] |

| Rouville | 19.3 | 1913 | 1956 | Also called Cordon Road. |

| Ruisseau Barré | 21.6 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| Marieville | 22.4 | 1913 | 1956 | |

| St. Angèle de Monnoir | 26.1 | 1926 | 1951 | |

| Monnoir Road | 24.6 | 1914 | 1951 | |

| Rougemont | 27.5 | 1914 | 1951 | |

| St. Césaire | 31.2 | 1914 | 1951 | |

| Jackman Road | 33.9 | 1915 | 1951 | |

| D'Arcy Corners | 36.1 | 1915 | 1951 | |

| Abbotsford | 38.0 | 1915 | 1951 | |

| Marshall Road | 38.7 | 1916 | 1951 | |

| Parish Line | 40.9 | 1916 | 1951 | |

| Mawcook & Milton | 42.6 | 1916 | 1951 | |

| Granby West | 45.7 | 1916 | 1951 | |

| Granby (MSC) | 46.7 | 1916 | 1925 | Located on the ground floor of the Bradford building at the corner of Drummond, City and Main streets. The terminal included a waiting area, and counters for passengers and freight.[55] |

| Granby (CN) | 47.5 | 1925 | 1951 | CN train station on the south side of the Yamaska River.[56] |

Legacy

Passenger Rail Service

CN continued to run diesel passenger trains for a short time between Montreal Central Station and Granby, and onward to Waterloo, using the M&SCRC's track after its junction with the CN St-Hyacinthe line. Service was finally cut on May 1, 1961 following an approval by the Federal Board of Transport Commissioners.[57]

Communities

The offering of suburban service to Montreal allowed new communities to spring up along the railway. Many were English-speaking immigrants working in the rail yards of Montreal who would commute into the city. Though many Anglophones left these neighbourhoods following the election of the Parti Québécois in 1976 and the referendum on sovereignty in 1980, their legacy can be found in the names of boroughs (Greenfield Park) and streets (i.a. Kensington, Cornwall, Glenn) that retain their British heritage.[58]

Stations and Buildings

The building that served as the Montreal terminal is still standing today.

The CN station that served as the terminus in Granby was demolished in 1993 and a replica built a few hundred meters away.[59]

The workshop and garage located in Granby was demolished in 2009. A small public place now stands in its place, and the "M&SCRy." stone engaging and the facade with doors have been preserved as a monument.[60]

Track

Track that was part of the interurban service between Mackayville and the junction at Eastern Greenfield, is today part of CN's Rouses Point subdivision and used by Amtrak's Adirondack daily between New York Penn Station and Montreal Central Station. The Adirondack does not service any former station of the M&SCRC.

CN later fully abandoned the rail line between Marieville and Granby in 1993.[61] In 2013, the Quebec Ministry of transportation purchased a 22 kilometre stretch of the disused right of way between Longueuil and Chambly. No transit plans have been announced.[62]

Today, much of the rail line's right-of-way has since been converted into cycling paths, including La Route des champs, a span of about 40 kilometres between Marieville and Granby.[63]

La Montée du Chemin Chambly,[64] a part of Route Verte 1 and the Trans Canada Trail, follows the path of the railway between the borough of Saint-Hubert in Longueuil and the city of Carignan.

Preserved rolling stock

Some rail cars have been preserved in museum collections. Examples include:

- Interurban streetcar M&SC 611[65] and Interurban railcar M&SC 104[66] have been preserved in the collection at the Exporail Canadian Railway Museum in Saint-Constant, Quebec.

- Interurban streetcar M&SC 610 is at the Seashore Trolley Museum in Kennebunkport, Maine.

- Interurban railcar M&SC 107 is in the collection of the Halton County Radial Railway museum.

Notes

- ^ Smith 1996 p36

- ^ Smith 1996 p34

- ^ Smith 1996 p36

- ^ Canada (1897). "An Act to incorporate the Montreal and Southern Counties Railway Company." Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, Vol. 2. Chap. 56. p107-109. Ottawa: Brown Chamberlin, Law Printer to the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty.

- ^ Smith (1996) p33.

- ^ Murphy (1981) p. 169.

- ^ Murphy (1981) p. 168.

- ^ Murphy 1981 p169

- ^ Smith (1996) p35

- ^ Ministry of Culture and Communications (Quebec). Site du patrimoine du Vieux-Longueuil. Accessed on 2017-02-13.

- ^ Smith (1996) p. 35.

- ^ Smith (1996) p. 35.

- ^ Smith (1996) p. 35.

- ^ Gendron et al. p. 1

- ^ Smith (1996) p. 36

- ^ The Electrical News (1915).

- ^ Due (1966) p. 23

- ^ Based on data from Canadian census.Canada. Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1925). Sixth Census of Canada. Bulletin IX. Population of Quebec, 1921. General Summary by Electoral Districts, Counties and Urban and Rural Sub-divisions (in English and French). pp. 10–11, 30–31 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gendron et al. p.1

- ^ Gendron et al. p.1

- ^ Gendron et al. p.1

- ^ Société historique du Marigot L'Évolution des moyens de transport et des voies de communication

- ^ Smith 1996 p36

- ^ Société historique Marigot, L'Évolution des moyens de transport et des voies de communication

- ^ Collin & Poitras p.286

- ^ Jacques Cartier Bridge, Montreal Insites

- ^ Smith 1996 p36

- ^ Grumley (2010) p. 19.

- ^ Due (1966).

- ^ Smith (1996) p. 36

- ^ Due (1966).

- ^ Canada-Rail. Montreal and Southern Counties Railway.

- ^ Angus (1981) p222.

- ^ Lavallée, Omer S.A. (October 1960). "Farnham - Century-old Rail Centre" (PDF). CRHA News Report. No. 115. Montreal: The Canadian Railroad Historical Association. p. 55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ^ Canada-Rail. Montreal and Southern Counties Railway

- ^ Murphy (1981) p. 174

- ^ Murphy (1981) p. 174

- ^ Oakley, Chambly County High School & Chambly Academy Alumni Association

- ^ Canadian Rail (1981) p166.

- ^ Due (1966).

- ^ Due (1966)

- ^ Due (1966)

- ^ Gendron et al. p.1

- ^ The Electrical News (1915).

- ^ The Electrical News (1915).

- ^ Smith (1996) pp. 36-37.

- ^ The Electrical Times (1915).

- ^ Name spellings and typography according to the convention used by the company. Based on, among other sources, information in QUEBEC & LABRADOR RAILWAYS – SL 150, PASSENGER STATIONS & STOPS.

- ^ Distance in miles, as was the convention at the time of the company's existence. Based on information in QUEBEC & LABRADOR RAILWAYS – SL 150, PASSENGER STATIONS & STOPS.

- ^ Murphy (1981)

- ^ Victoria Ave & The Village. Chambly County and Chambly Academy Alumni Association.

- ^ Manning, V.M. "Station House School" Landmarks. (n.d.) East Greenfield, Quebec. Last accessed: 2018-03-08

- ^ Cameron, Norman James. Memories of Brentwood and Its Inhabitants. (n.d.) East Greenfield, Quebec. Last accessed: 2018-03-08

- ^ Ville de Richelieu. Histoire. Last accessed 2018-07-20.

- ^ Gendron et al. p.1

- ^ Gendron et al. p.1

- ^ "Observations" (PDF). CRHA News Report (in English and French). No. 121. Montreal: The Canadian Railroad Historical Association. April 1961. pp. 50–51. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Erskine-Henry, Kevin (March–April 2009). "Trolley line villages: Remembering the railway that spawned South Shore settlement" (PDF). Quebec Heritage News. Vol. 5, no. 2. Sherbrooke: Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network. p. 5.

- ^ Branchline 1993 p5.

- ^ Authier, Isabel (2008-12-23). "L'ancien bâtiment d'Agropur sera démoli" [Former Agropur building to be demolished]. La Voix de l'Est (in French). Sherbrooke. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- ^ Decision No. 116-R-1993, Canadian Transportation Agency, 1993

- ^ "Québec acquiert un corridor ferroviaire reliant Chambly et Longueuil", Myriam Tougas-Dumesnil, Chambly Express

- ^ La Route des Champs, Tourisme au Coeur de la Montérégie, 2017.

- ^ La Montée du Chemin Chambly, PistesCyclables.ca

- ^ Interurban car MSC 611. Exporail. Last accessed: 2017-02-13

- ^ Interurban railcar M&SC 104. Exporail. Last accessed: 2017-02-13

References

Books

- Clegg, Anthony; Omer Lavallée (1966). Catenary through the Counties: The story of Montreal & Southern Counties Railway. St. Hilaire, Quebec: The Classic Era in cooperation with Canadian Railroad Historical Association. pp. 64 p. illus. (part col.), maps (part col.) 23 x 29 cm. LCCN 70413781. OCLC 25171.

- Due, John F. (1966). The Intercity Electric Railway Industry in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 118 p. ISBN 9781442638440.

- Grumley, J.R. Thomas, Montreal & Southern Counties Railway Co., Ottawa, Bytown Railway Society, 2004, 67 pages. ISBN 0-921871-07-4, ISBN 978-0-921871-07-1 OCLC 56011524

Articles

- "Information Line" (PDF). Branchline. Vol. 32, no. 8. Ottawa: Bytown Railway Society. September 1993. p. 5. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- "Montreal and Southern Counties Railway". Canada-Rail. Retrieved 2018-02-13.

- "Montreal & Southern Counties, Part II" (PDF). Canadian Rail (in English and French). No. 354. Montreal: The Canadian Railroad Historical Association. July 1981. pp. 198–223. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- "Victoria Ave & The Village". Chambly County and Chambly Academy Alumni Association. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- "The Montreal and Southern Counties Ry" (images). The Electrical News. No. 394. June 1915. pp. 103–104. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- Gendron, Mario; Rochon, Johanne; Racine, Richard (Autumn 2007). "Quand les tramways circulaient à Granby" [When Streetcars Ran in Granby] (PDF). L'historien régional (in French). Vol. 7, no. 4. Société d'histoire de la Haute-Yamaska. p. 1.

- Grumley, J.R. Thomas (September–October 1986). "The Montreal & Southern Counties Railway Company (1909 – 1956)" (PDF). Histoire Québec. Vol. 16, no. 1. Histoire Québec. pp. 18–20. ISSN 1923-2101. Retrieved 2018-02-13.

- Lambert, Ed (September–October 1986). "Memories of a traction fan's trip to Granby" (PDF). Canadian Rail. No. 394. Montreal: The Canadian Railroad Historical Association. pp. 148–153. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- McConnell, R. "St. Lambert Trains & Trams". Chambly County and Chambly Academy Alumni Association. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- Murphy, M. Peter (June 1981). "The Montreal and Southern Counties Railway" (PDF). Canadian Rail. No. 353. Montreal: The Canadian Railroad Historical Association. pp. 166–191. ISSN 0008-4875. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- Oakley, Donald (2016-07-08). "Saint Lambert (1930s & 1940s)". Chambly County and Chambly Academy Alumni Association. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- Smith, T.C.H. (March–April 1996) [First published in 1939]. "The Montreal and Southern Counties Railway" (PDF). Canadian Rail. No. 451. Montreal: The Canadian Railroad Historical Association. pp. 31–46. ISSN 0008-4875. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- "L'Évolution des moyens de transport et des voies de communication" [The Evolution of Means and Routes of Transportation]. Société historique du Marigot (in French). Retrieved 2018-02-13.

Maps of railway lines and stations

- Underwriters' Survey Bureau Ltd (1953). Insurance plan of the city of St. Lambert, Quebec embracing the towns of Lemoyne and Preville (Map). 1:12,000. Toronto: Underwriters' Survey Bureau. p. 4 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

- Underwriters' Survey Bureau Ltd (April 1953). Insurance plan of the city of St. Lambert, Quebec embracing the towns of Lemoyne and Preville (Map). 1:1,200. Toronto: Underwriters' Survey Bureau. p. 6 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

- Underwriters' Survey Bureau Ltd (April 1953). Insurance plan of the city of St. Lambert, Quebec embracing the towns of Lemoyne and Preville (Map). 1:1,200. Toronto: Underwriters' Survey Bureau. p. 13 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

- Underwriters' Survey Bureau Ltd (June 1962). Insurance plan of the town of Chambly, Que., including town of Fort Chambly and village of Richelieu (Map). 1:12,000. Toronto: Underwriters' Survey Bureau. pp. 2–3 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

- Underwriters' Survey Bureau Ltd (June 1962). Insurance plan of the town of Chambly, Que., including town of Fort Chambly and village of Richelieu (Map). 1:1,200. Toronto: Underwriters' Survey Bureau. p. 25 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Other

- Fergusson, Jim (2017-11-10), QUEBEC & LABRADOR RAILWAYS – SL 150: PASSENGER STATIONS & STOPS (PDF), p. 5, retrieved 2018-02-11

External links

- Canadian Rail no 353 (1981) Archived 2013-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- East Greenfield: Montreal and Southern Counties Railway

- Trainweb.com : Montreal and Southern Counties

- Montreal Area Historical Rail Map (shows Montreal and Southern Counties Railway)