Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery | |

|---|---|

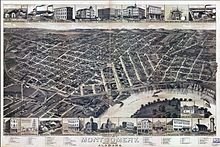

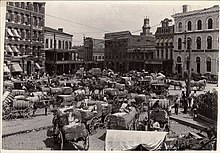

Montgomery along the Alabama River Commerce Street, downtown | |

| Nickname(s): "The Gump", "Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement", "Cradle of the Confederacy" | |

| Motto: "Capital of Dreams"[1] | |

Interactive map of Montgomery | |

| Coordinates: 32°22′3″N 86°18′0″W / 32.36750°N 86.30000°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Montgomery |

| Incorporated | December 3, 1819[2][3] |

| Named for | Richard Montgomery |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Steven L. Reed (D) |

| • City Council | District 1 – Ed Grimes District 2 – Julie T. Beard District 3 – Marche Johnson District 4 – Franetta Riley District 5 – Cornelius Calhoun District 6 – Oronde Mitchell District 7 – Andrew Szymanski District 8 – Glen O. Pruitt, Jr. District 9 – Charles W. Jinright |

| Area | |

| 162.27 sq mi (420.28 km2) | |

| • Land | 159.86 sq mi (414.03 km2) |

| • Water | 2.41 sq mi (6.25 km2) |

| Elevation | 240 ft (73 m) |

| Population | |

| 200,603 | |

• Estimate (2022)[7] | 196,986 |

| • Rank | US: 133rd AL: 3rd |

| • Density | 1,232/sq mi (475.8/km2) |

| • Urban | 254,348 (US: 159th) |

| • Urban density | 1,752.9/sq mi (676.8/km2) |

| • Metro | 385,460 (US: 142nd) |

| • Metro density | 142.0/sq mi (54.83/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | ZIP Codes[8] |

| Area code | 334 |

| FIPS code | 01-51000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0165344[5] |

| Website | montgomeryal.gov |

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County.[9] Named for Continental Army Major General Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. The population was 200,603 at the 2020 census.[6] It is the third-most populous city in the state after Huntsville and Birmingham, and is the 133rd most populous in the United States. The Montgomery Metropolitan Statistical Area's population in 2022 was 385,460; it is the fourth largest in the state and 142nd among United States metropolitan areas.

The city was incorporated in 1819 as a merger of two towns situated along the Alabama River. It replaced Tuscaloosa as the state capital in 1846, representing the shift of power to the south-central area of Alabama with the growth of cotton as a commodity crop of the Black Belt and the rise of Mobile as a mercantile port on the Gulf Coast. In February 1861, Montgomery was chosen the first capital of the Confederate States of America, which it remained until the Confederate seat of government moved to Richmond, Virginia, in May of that year. In the middle of the 20th century, Montgomery was a major center of events and protests in the Civil Rights Movement,[10] including the Montgomery bus boycott and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

In addition to housing many Alabama government agencies, Montgomery has a large military presence, due to Maxwell Air Force Base. It has three public universities (Alabama State University, Troy University (Montgomery campus), and Auburn University at Montgomery), two private post-secondary institutions (Faulkner University and Huntingdon College), high-tech manufacturing (particularly Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama), and many cultural attractions, such as the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Montgomery has also been recognized nationally for its downtown revitalization and new urbanism projects. It was one of the first cities in the nation to implement SmartCode Zoning.

History

Prior to European colonization, the east bank of the Alabama River was inhabited by the Alibamu tribe of Native Americans. The Alibamu and the Coushatta, who lived on the west side of the river, were descended from the Mississippian culture. This civilization had numerous chiefdoms throughout the Midwest and South along the Mississippi and its tributaries, and had built massive earthwork mounds as part of their society about 950–1250 AD. Its largest location was at Cahokia, in present-day Illinois east of St. Louis.

The historic tribes spoke mutually intelligible Muskogean languages, which were closely related. Present-day Montgomery is built on the site of two Alibamu towns: Ikanatchati (Ekanchattee or Ecunchatty or Econachatee), meaning "red earth;" and Towassa, built on a bluff called Chunnaanaauga Chatty.[11] The first Europeans to travel through central Alabama were Hernando de Soto and his expedition, who in 1540 recorded going through Ikanatchati and camping for one week in Towassa.

The next recorded European encounter occurred more than a century later, when an English expedition from Carolina went down the Alabama River in 1697. The first permanent European settler in the Montgomery area was James McQueen, a Scots trader who settled there in 1716.[12] He married a high-status woman in the Coushatta or Alabama tribe. Their mixed-race children were considered Muskogean, as both tribes had a matrilineal system of property and descent. The children were always considered born into their mother's clan, and gained their status from her people.

In 1785, Abraham Mordecai, a war veteran from a Sephardic Jewish family of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, established a trading post.[13] The Coushatta and Alabama had gradually moved south and west in the tidal plain. After the French were defeated by the British in 1763 in the Seven Years' War and ceded control of their lands, these Native American peoples moved to parts of present-day Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, then areas of Spanish rule, which they thought more favorable than British-held areas. By the time Mordecai arrived, Creek had migrated into and settled in the area, as they were moving away from Cherokee and Iroquois warfare to the north. Mordecai married a Creek woman. When her people had to cede most of their lands after the 1813-14 Creek War, she joined them in removal to Indian Territory. Mordecai brought the first cotton gin to Alabama.[13]

The Upper Creek were able to discourage most white immigration until after the conclusion of the Creek War. Following their defeat by General Andrew Jackson in August 1814, the Creek tribes were forced to cede 23 million acres to the United States, including remaining land in today's Georgia and most of today's central and southern Alabama. In 1816, the Mississippi Territory (1798–1817) organized Montgomery County. Its former Creek lands were sold off the next year at the federal land office in Milledgeville, Georgia.

The first group of white settlers to come to the Montgomery area was headed by General John Scott. This group founded Alabama Town about 2 miles (3 km) downstream on the Alabama River from present-day downtown Montgomery. In June 1818, county courts were moved from Fort Jackson to Alabama Town. Alabama was admitted to the Union in December 1819.

Soon after, Andrew Dexter Jr. founded New Philadelphia, the present-day eastern part of downtown. He envisioned a prominent future for his town; he set aside a hilltop known as "Goat Hill" as the future site of the state capitol building. New Philadelphia soon prospered, and Scott and his associates built a new town adjacent, calling it East Alabama Town. Originally rivals, the towns merged on December 3, 1819, and were incorporated as the town of Montgomery,[2][14] named for Richard Montgomery, an American Revolutionary War general.

Slave traders used the Alabama River to deliver enslaved laborers to planters, to work the cotton. Buoyed by the revenues of the cotton trade at a time of high market demand, the newly united Montgomery grew quickly. In 1822, the city was designated as the county seat. A new courthouse was built at the present location of Court Square, at the foot of Market Street (now Dexter Avenue).[15] Court Square had one of the largest slave markets in the South. The state capital was moved from Tuscaloosa to Montgomery, on January 28, 1846.[16]

As state capital, Montgomery began to influence state politics, and it would also play a prominent role on the national stage. Beginning February 4, 1861, representatives from Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina met in Montgomery, host of the Southern Convention,[17] to form the Confederate States of America. Montgomery was named the first capital of the nation, and Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president on the steps of the State Capitol. The capital was later moved to Richmond, Virginia.

On April 12, 1865, following the Battle of Selma, Major General James H. Wilson captured Montgomery for the Union.[18]

In 1886 Montgomery became the first city in the United States to install citywide electric streetcars along a system that was nicknamed the Lightning Route. Residents followed the streetcar lines to settle in new housing in what were then "suburban" locations.

As the Reconstruction era ended, mayor W. L. Moses asked the state legislature to gerrymander city boundaries. It complied and removed the districts where African Americans lived, restoring white supremacy to the city's demographics and electorate. This prevented African Americans from being elected in the municipality and denied them city services.[19]

On February 12, 1945, a devastating and deadly tornado struck the western portion of the city. The tornado killed 26 people, injured 293 others, and caused a city-wide blackout which lasted for hours.[20] The United States Weather Bureau would describe this tornado as "the most officially observed one in history".[21]

In the post-World War II era, returning African-American veterans were among those who became active in pushing to regain their civil rights in the South: to be allowed to vote and participate in politics, to freely use public places, to end segregation. According to the historian David Beito of the University of Alabama, African Americans in Montgomery "nurtured the modern civil rights movement."[10] African Americans comprised most of the customers on the city buses, but were forced to give up seats and even stand in order to make room for whites. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, sparking the Montgomery bus boycott. Martin Luther King Jr., then the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and E.D. Nixon, a local civil rights advocate, founded the Montgomery Improvement Association to organize the boycott. In June 1956, the US District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson ruled that Montgomery's bus racial segregation was unconstitutional. After the US Supreme Court upheld the ruling in November, the city desegregated the bus system, and the boycott was ended.[22]

In separate action, integrated teams of Freedom Riders rode South on interstate buses. In violation of federal law and the constitution, bus companies had for decades acceded to state laws and required passengers to occupy segregated seating in Southern states. Opponents of the push for integration organized mob violence at stops along the Freedom Ride. In Montgomery, there was police collaboration when a white mob attacked Freedom Riders at the Greyhound Bus Station in May 1961.[23] Outraged national reaction resulted in the enforcement of desegregation of interstate public transportation.

Martin Luther King Jr. returned to Montgomery in 1965. Local civil rights leaders in Selma had been protesting Jim Crow laws and practices that raised barriers to blacks registering to vote. Following the shooting of a man after a civil rights rally, the leaders decided to march to Montgomery to petition Governor George Wallace to allow free voter registration. The violence they encountered from county and state highway police outraged the country. The federal government ordered National Guard and troops to protect the marchers. Thousands more joined the marchers on the way to Montgomery, and an estimated 25,000 marchers entered the capital to press for voting rights. These actions contributed to Congressional passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, to authorize federal supervision and enforcement of the rights of African Americans and other minorities to vote.

On February 7, 1967, a devastating fire broke out at Dale's Penthouse, a restaurant and lounge on the top floor of the Walter Bragg Smith apartment building (now called Capital Towers) at 7 Clayton Street downtown. Twenty-six people died.[24]

In recent years, Montgomery has grown and diversified its economy. Active in downtown revitalization, the city adopted a master plan in 2007; it includes the revitalization of Court Square and the riverfront, renewing the city's connection to the river.[25] Many other projects under construction include the revitalization of Historic Dexter Avenue, pedestrian and infrastructure improvements along the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, and the construction of a new environmental park on West Fairview Avenue.

Geography

Montgomery is located at 32°21′42″N 86°16′45″W / 32.36167°N 86.27917°W.[26]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 162.27 square miles (420.3 km2), of which 159.86 square miles (414.0 km2) is land and 2.41 square miles (6.2 km2) (0.52%) is water.[4] The city is built over rolling terrain at an elevation of about 220 feet (67 m) above sea level.[27]

Cityscape

Downtown Montgomery lies along the southern bank of the Alabama River, about 6 miles (10 km) downstream from the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers. The most prominent feature of Montgomery's skyline is the 375 ft (114 m), RSA Tower, built in 1996 by the Retirement Systems of Alabama.[28] Other prominent buildings include 60 Commerce Street, 8 Commerce Street, and the RSA Dexter Avenue Building. Downtown also contains many state and local government buildings, including the Alabama State Capitol. The Capitol is located atop a hill at one end of Dexter Avenue, along which also lies the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. was pastor. Both the Capitol and Dexter Baptist Church are recognized as National Historic Landmarks by the U.S. Department of the Interior.[29] Other notable buildings include RSA Dexter Avenue, RSA Headquarters, Alabama Center for Commerce, RSA Union, and the Renaissance Hotel and Spa.[30]

One block south of the Capitol is the First White House of the Confederacy, the 1835 Italianate-style house in which President Jefferson Davis and family lived while the Confederate capital was in Montgomery. Montgomery's third National Historic Landmark is Union Station. Passenger train service to Montgomery ceased in 1989. Today Union Station is part of the Riverfront Park development, which includes an amphitheater, a riverboat dock,[31] a river walk, and Riverwalk Stadium.[32]

The completion of a 112,000-square-foot (10,400 m2) space in 2007, the Convention Center, has encouraged growth and activity in the downtown area and attracted more high-end retail and restaurants.[33] Three blocks east of the Convention Center, Old Alabama Town showcases more than 50 restored buildings from the 19th century. The Riverwalk is part of a larger plan to revitalize the downtown area and connect it to the waterfront. The plan includes urban forestry, infill development, and façade renovation to encourage business and residential growth.[25]

Other downtown developments include historic Dexter Avenue, which will be the center of a Market District. A$6 million streetscape project is improving its design.[34] Maxwell Boulevard is home to the newly built Wright Brothers Park. High-end apartments are planned for this area. The Bell Building, located across from the Rosa Parks Library and Museum, is being redeveloped for mixed-use retail and residential space.[35]

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in downtown Montgomery on April 26, 2018. Founded by the Equal Justice Initiative, it acknowledges the historic past of racial terrorism and lynching in America.[36]

South of downtown, across Interstate 85, lies Alabama State University. ASU's campus was built in Colonial Revival architectural style from 1906 until the beginning of World War II.[37][38] Surrounding ASU are the Garden District and Cloverdale Historic District. Houses in these areas date from around 1875 until 1949, and are in Late Victorian and Gothic Revival styles.[38] Huntingdon College is on the southwestern edge of Cloverdale. The campus was built in the 1900s in Tudor Revival and Gothic Revival styles.[39] ASU, the Garden District, Cloverdale, and Huntingdon are all listed on the National Register of Historic Places as historic districts.[38]

Montgomery's east side is the fastest-growing part of the city.[40] Development of the Dalraida neighborhood, along Atlanta Highway, began in 1909, when developers Cook and Laurie bought land from the Ware plantation. A Scotsman, Georgie Laurie named the area for Dál Riata, a 6th-7th century Gaelic overkingdom; a subsequent misspelling in an advertisement led to the current spelling. The first lots were sold in 1914.[41] The city's two largest shopping malls (Eastdale Mall and The Shoppes at Eastchase),[42][43] as well as many big-box stores and residential developments, are on the east side.

The area is also home of the Wynton M. Blount Cultural Park. This 240-acre (1.0 km2) park contains the Alabama Shakespeare Festival and Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts.[44]

Revitalization

Montgomery has been recognized nationally for its continuing downtown revitalization. In the early 2000s, the city constructed the Montgomery Biscuits minor league baseball stadium and Riverfront Park. Following those developments, hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested by private companies that have adapted old warehouses and office buildings into loft apartments, restaurants, retail, hotels, and businesses. The demand for downtown living space has risen, as people want to have walkable, lively neighborhoods. More than 500 apartment units are under construction, including The Heights on Maxwell Boulevard, The Market District on Dexter Avenue, the Kress Building on Dexter Avenue, The Bell Building on Montgomery Street, and a new complex by the convention center. Additionally, Montgomery has recently opened a 50 million dollar white water park on July 7, located off Maxwell Boulevard.[45]

Climate

Montgomery has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with short, mild winters, warm springs and autumns, and long, hot, humid summers. The daily average temperature in January is 46.6 °F (8.1 °C), and there are 3.4 days of sub 20 °F (−7 °C) lows; 10 °F (−12 °C) and below is extremely rare. The daily average in July is 81.8 °F (27.7 °C), with highs exceeding 90 °F (32.2 °C) on 86 days per year and 100 °F (37.8 °C) on 3.9. Summer afternoon heat indices, much more often than the actual air temperature, are frequently at or above 100 °F.[46] The diurnal temperature variation tends to be large in spring and autumn. Rainfall is well-distributed throughout the year, though February, March and July are the wettest months, while October is significantly the driest month. Snowfall occurs only during some winters, and even then is usually light. Substantial snowstorms are rare, but do occur approximately once every 10 years. Extremes range from −5 °F (−21 °C) on February 13, 1899[47] to 107 °F (42 °C) on July 7, 1881.[48]

Thunderstorms bring much of Montgomery's rainfall. These are common during the summer months but occur throughout the year. Severe thunderstorms – producing large hail and damaging winds in addition to the usual hazards of lightning and heavy rain – can occasionally occur, particularly during the spring. Severe storms also bring a risk of tornadoes. Sometimes, tropical disturbances – some of which strike the Gulf Coast as hurricanes before losing intensity as they move inland – can bring very heavy rains.

| Climate data for Montgomery, Alabama (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1872–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

86 (30) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

106 (41) |

107 (42) |

106 (41) |

106 (41) |

102 (39) |

91 (33) |

85 (29) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.6 (24.2) |

78.8 (26.0) |

84.7 (29.3) |

87.4 (30.8) |

93.1 (33.9) |

96.9 (36.1) |

98.3 (36.8) |

98.9 (37.2) |

95.7 (35.4) |

90.1 (32.3) |

82.7 (28.2) |

77.6 (25.3) |

99.6 (37.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.8 (15.4) |

64.7 (18.2) |

71.9 (22.2) |

78.8 (26.0) |

86.0 (30.0) |

91.5 (33.1) |

93.7 (34.3) |

93.6 (34.2) |

89.3 (31.8) |

80.2 (26.8) |

69.8 (21.0) |

61.9 (16.6) |

78.4 (25.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 48.1 (8.9) |

52.6 (11.4) |

59.2 (15.1) |

65.7 (18.7) |

73.6 (23.1) |

80.2 (26.8) |

82.9 (28.3) |

82.5 (28.1) |

77.8 (25.4) |

67.4 (19.7) |

56.6 (13.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

66.4 (19.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 36.5 (2.5) |

40.4 (4.7) |

46.5 (8.1) |

52.6 (11.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

69.0 (20.6) |

72.1 (22.3) |

71.4 (21.9) |

66.3 (19.1) |

54.5 (12.5) |

43.3 (6.3) |

38.6 (3.7) |

54.4 (12.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.1 (−7.2) |

23.6 (−4.7) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

37.3 (2.9) |

47.3 (8.5) |

60.1 (15.6) |

66.7 (19.3) |

64.2 (17.9) |

53.0 (11.7) |

37.3 (2.9) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 0 (−18) |

−5 (−21) |

17 (−8) |

28 (−2) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

59 (15) |

56 (13) |

39 (4) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

5 (−15) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.64 (118) |

4.88 (124) |

5.21 (132) |

3.99 (101) |

3.88 (99) |

4.08 (104) |

5.06 (129) |

4.02 (102) |

3.69 (94) |

2.87 (73) |

3.85 (98) |

4.99 (127) |

51.16 (1,299) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.4 (1.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.4 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 10.3 | 11.7 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 10.2 | 106.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.8 | 66.5 | 66.0 | 66.8 | 70.6 | 71.7 | 75.7 | 76.0 | 73.9 | 71.1 | 71.7 | 70.9 | 70.9 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 34.9 (1.6) |

36.9 (2.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

66.9 (19.4) |

70.7 (21.5) |

70.3 (21.3) |

65.1 (18.4) |

53.4 (11.9) |

45.5 (7.5) |

38.5 (3.6) |

53.2 (11.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 153.1 | 166.0 | 219.4 | 250.8 | 267.4 | 261.8 | 262.1 | 251.9 | 226.4 | 228.3 | 171.4 | 153.1 | 2,611.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 48 | 54 | 59 | 64 | 62 | 61 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 65 | 54 | 49 | 59 |

| Source: NOAA (snow 1981–2010, relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[49][50][51][52][53] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 695 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,179 | 213.5% | |

| 1850 | 4,728 | 117.0% | |

| 1860 | 8,843 | 87.0% | |

| 1870 | 10,588 | 19.7% | |

| 1880 | 16,713 | 57.8% | |

| 1890 | 21,883 | 30.9% | |

| 1900 | 30,346 | 38.7% | |

| 1910 | 38,136 | 25.7% | |

| 1920 | 43,464 | 14.0% | |

| 1930 | 66,079 | 52.0% | |

| 1940 | 78,084 | 18.2% | |

| 1950 | 106,525 | 36.4% | |

| 1960 | 134,393 | 26.2% | |

| 1970 | 133,386 | −0.7% | |

| 1980 | 177,857 | 33.3% | |

| 1990 | 187,106 | 5.2% | |

| 2000 | 201,568 | 7.7% | |

| 2010 | 205,764 | 2.1% | |

| 2020 | 200,603 | −2.5% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 196,986 | [7] | −1.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[54] 2020 Census[6] | |||

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[55] | Pop 2010[56] | Pop 2020[57] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 94,868 | 74,227 | 57,071 | 47.07% | 36.07% | 28.45% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 99,631 | 116,001 | 120,349 | 49.43% | 56.38% | 59.99% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 468 | 449 | 322 | 0.23% | 0.22% | 0.16% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 2,120 | 4,580 | 7,171 | 1.05% | 2.23% | 3.57% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 66 | 79 | 105 | 0.03% | 0.04% | 0.05% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 173 | 184 | 648 | 0.09% | 0.09% | 0.32% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,758 | 2,246 | 5,268 | 0.87% | 1.09% | 2.63% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,484 | 7,998 | 9,669 | 1.23% | 3.89% | 4.82% |

| Total | 201,568 | 205,764 | 200,603 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 200,603 people, 82,835 households, and 49,303 families residing in the city.[58] There were 93,920 housing units.

2010 census

As of the 2010 census, there were 205,764 people, 81,486 households, out of which 29% had children under the age of 18 living with them. The racial makeup of the city was 37.3% White, 56.6% Black, 2.2% Asian, 0.2% Native American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.2% from other races, and 1.3% from two or more races. 3.9% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. Non-Hispanic Whites were 36.1% of the population in 2010, down from 66% in 1970. The population density varies in different parts of the city; East Montgomery (Taylor Rd and East), the non-Hispanic White population is 74.5%, African American 8.3%, Latino 3.2%, other non-white races carry 2.7% of the population.

The city population was spread out, with 24.9% under the age of 18, 11.7% from 18 to 24, 27.3% from 25 to 44, 24.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.5 males. The median income for a household in the city was $41,380, and the median income for a family was $53,125. Males had a median income of $40,255 versus $33,552 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,139. About 18.2% of families and 21.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 34.8% of those under age 18 and 8.4% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Montgomery's central location in Alabama's Black Belt has long made it a processing hub for commodity crops such as cotton, peanuts, and soybeans. In 1840 Montgomery County led the state in cotton production,[59] and by 1911, the city processed 160,000–200,000 bales of cotton annually.[60] Montgomery has also had large metal fabrication and lumber production sectors.[60]

Due to its location along the Alabama River and extensive rail connections, Montgomery has been and continues to be a regional distribution hub for a wide range of industries. Since the late 20th century, it has diversified its economy, achieving increased employment in sectors such as healthcare, business, government, and manufacturing. Today, the city's Gross Metropolitan Product is $12.15 billion, representing 8.7% of the gross state product of Alabama.[61]

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data from October 2008, the largest sectors of non-agricultural employment were: Government, 24.3%; Trade, Transportation, and Utilities, 17.3% (including 11.0% in retail trade); Professional and Business Services, 11.9%; Manufacturing, 10.9%; Education and Health Services, 10.0% (including 8.5% in Health Care & Social Assistance); Leisure and Hospitality, 9.2%; Financial Activities, 6.0%, Natural Resources, Mining and Construction, 5.1%; Information, 1.4%; and Other services 4.0%. Unemployment for the same period was 5.7%, 2.5% higher than October 2007.[62] The city also draws in workers from the surrounding area; Montgomery's daytime population rises 17.4% to 239,101.

Top employers

According to the city's 2022 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[63][64] the largest employers in the city are:

| Number | Company/Organizations | Product/Service | Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base | Military Base | 12,280 |

| 2 | State of Alabama | State Government | 10,315 |

| 3 | Montgomery Public Schools | Public Schools | 4,524 |

| 4 | Baptist Health | Hospitals/Clinics | 4,300 |

| 5 | Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama | Automobile Manufacturing | 3,530 |

| 6 | ALFA Companies | Insurance Companies | 2,568 |

| 7 | City of Montgomery | Local Government | 2,500 |

| 8 | Business & Enterprise Systems | Software Development | 1,350 |

| 9 | Jackson Hospital & Clinic, Inc. | Hospitals/Clinics | 1,300 |

| 10 | Koch Foods | Poultry Processing | 1,250 |

| 11 | MOBIS Alabama | Automobile Manufacturing | 1,010 |

| 12 | Baptist Medical Center South | Hospitals/Clinics | 980 |

| 13 | Rheem Water Heaters | Water Heater Manufacturing | 920 |

| 14 | UPS | Distribution/Logistics | 850 |

| 15 | Glovis Alabama, LLC | Warehousing and Logistics | 832 |

| 16 | Convergent Outsourcing, Inc. | Customer Contact Center | 736 |

| 17 | Montgomery County Commission | Local Government | 700 |

| 18 | Alabama Power Company | Utility | 660 |

| 19 | Auburn University at Montgomery | University | 576 |

| 20 | Glovis America | Logistics | 545 |

According to the Living Wage Calculator, the living wage for the city is US$19.73 per hour (or $41,038 per year) for an individual and $37.14 per hour ($77,251 per year) for a family of four.[65] These are slightly higher than the state averages of $20.15 per hour for an individual and $41.11 for a family of four.[66] US$7.25 per hour minimum wage in Alabama.[67]

Health care

Montgomery serves as a hub for healthcare in the central Alabama and Black Belt region. Hospitals located in the city include Baptist Medical Center South on South East Boulevard, Baptist Medical Center East next to the campus of Auburn University Montgomery on Taylor Road, and Jackson Hospital, which is located next to Oak Park off interstate 85. Montgomery is also home to two medical school campuses: Baptist Medical Center South (run by University of Alabama at Birmingham) and Jackson Hospital (run by Alabama Medical Education Consortium).

Law and government

Montgomery operates under a Mayor–council government system. The mayor and council members are elected to four-year terms. The current mayor is Steven Reed,[68] who was elected as the city's first African-American mayor in a runoff election which was held on October 8, 2019.[69] The city is served by a nine-member city council, elected from nine single-member districts of equal size population.

As the seat of Montgomery County, the city is the location of county courts and the county commission, elected separately. Montgomery is the capital of Alabama, and hosts numerous state government offices, including the office of the Governor, the Alabama Legislature, and the Alabama Supreme Court.

At the federal level, Montgomery is part of Alabama's 2nd, 7th, and 3rd Congressional district, currently represented by Barry Moore, Terri Sewell, and Mike Rogers, respectively. The 7th represents most of Western Montgomery, the 2nd Southern and Northern Montgomery, and the 3rd Eastern Montgomery.

Crime

| Montgomery | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2020) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 18 |

| Rape | 9 |

| Robbery | 141 |

| Aggravated assault | 354 |

| Total violent crime | 522 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 562 |

| Larceny-theft | 1,773 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 301 |

| Arson | 0 |

| Total property crime | 2,636 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. 2022 population: 196,986 Source: 2020 FBI UCR Data | |

According to the Uniform Crime Report statistics compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 2022, there were 522 violent crimes and 2,636 property crimes per 100,000 residents. Of these, the violent crimes consisted of 18 murders, 9 forcible rapes, 141 robberies and 354 aggravated assaults, while 562 burglaries, 1,773 larceny-thefts, 301 motor vehicle thefts and 0 acts of arson defined the property offenses.

According to the city, there were 75 homicides in 2023.[70]

Montgomery's violent crime rates compare unfavorably to other large cities in the state. In 2009, Montgomery's crime rates were favorable compared to other large Alabamian cities such as Huntsville, Mobile, and Birmingham. However, crime rose in the 2010s and early 2020s, leading to a record high of over 320 shooting victims and over 77 homicide victims in 2021.[71][72] In 2022 Montgomery's violent crime rate was 514 per 100,000, earning only a crime score rating of 9/100.[73] For property crimes, Montgomery's average is similar to Alabama's other large cities, but higher than the overall state and national averages.

Recreation

Montgomery has more than 1,600 acres of parkland, which are maintained and operated by the City of Montgomery Parks and Recreation Department. The department also operates 24 community centers, a skate park, two golf courses (Lagoon Park and Gateway Park), Cramton Bowl Stadium and Multiplex, two tennis centers (Lagoon Park and O'Conner), 65 playgrounds, 90 baseball/softball fields, 24 soccer fields including the Emory Folmar Soccer Facility, and one riverboat.[74]

Culture

Montgomery has one of the biggest arts scenes of any mid-sized city in America. The Winton M. Blount Cultural Park (named for Winton M. Blount) in east Montgomery is home to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. The museum's permanent collections include American art and sculpture, Southern art, master prints from European masters, and collections of porcelain and glass works.[75] The Society of Arts and Crafts operates a co-op gallery for local artists.[76]

Montgomery Zoo holds more than 500 animals, from five continents, in 40 acres (0.16 km2) of barrier-free habitats.[77] The Hank Williams Museum contains one of the largest collections of Williams memorabilia in the world.[78] The Museum of Alabama serves as the official state history museum and is located in the Alabama Department of Archives and History building downtown.[79] This museum was renovated and expanded in 2013 in a $10 million project that includes technological upgrades and many new exhibits and displays. The W. A. Gayle Planetarium, operated by Troy University, is one of the largest in the southeast United States and offers tours of the night sky and shows about current topics in astronomy. The planetarium was upgraded to a full-dome digital projector in 2014.[80]

Blount Park also contains the Alabama Shakespeare Festival's Carolyn Blount Theatre. The Shakespeare Festival presents year-round performances of both classic plays and performances of local interest, in addition to works of William Shakespeare.[81] The 1200-seat Davis Theatre for the Performing Arts, on the Troy University at Montgomery campus, opened in 1930 and was renovated in 1983. It houses the Montgomery Symphony Orchestra, Alabama Dance Theatre and Montgomery Ballet, as well as other theatrical productions.[82] The Symphony has been performing in Montgomery since 1979.[83] The Capri Theatre in Cloverdale was built in 1941, and today shows independent films.[84] The 1800-seat state-of-the-art Montgomery Performing Arts Center opened inside the newly renovated convention center downtown in 2007. It hosts a range of performances, from Broadway plays to concerts, and performers such as B. B. King, Gregg Allman, and Merle Haggard.

Numerous musical performers have roots in Montgomery: Toni Tennille of the duo The Captain and Tennille, jazz singer and pianist Nat King Cole, country singer Hank Williams,[85] blues singer Big Mama Thornton, Melvin Franklin of The Temptations, and guitarist Tommy Shaw of Styx.[86]

Author and artist Zelda Sayre was born in Montgomery. In 1918, she met F. Scott Fitzgerald, then a young soldier stationed at an Army post nearby. The house where they lived when first married is today operated as the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum.[87][88] Poet Sidney Lanier lived in Montgomery and Prattville immediately after the Civil War, while writing his novel Tiger Lilies.[89]

In addition to those notable earlier musicians, some of the rock bands from Montgomery have achieved national success since the late 20th century. Locals artists Trust Company were signed to Geffen Records in 2002. Hot Rod Circuit formed in Montgomery in 1997 under the name Antidote, but achieved success with Vagrant Records after moving to Connecticut.

Sports

Montgomery is home of the Montgomery Biscuits baseball team. The Biscuits play in the Class AA Southern League. They are affiliated with the Tampa Bay Rays, and play at Montgomery Riverwalk Stadium. Riverwalk Stadium hosted the NCAA Division II National Baseball Championship from 2004 until 2007. The championship had previously been played at Paterson Field in Montgomery from 1985 until 2003.[90] Riverwalk Stadium has also been host to two Southern League All-Star games in 2006 and 2015.

The Yokohama Tire LPGA Classic women's golf event is held at the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail at Capitol Hill in nearby Prattville.[91] Garrett Coliseum was the home of the now-defunct Montgomery Bears indoor football team.

Montgomery is also the site of sporting events hosted by the area's colleges and universities. The Alabama State University Hornets play in NCAA Division I competition in the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC). The football team plays at Hornet Stadium, the basketball teams play at the Dunn-Oliver Acadome, and the baseball team plays at the ASU Baseball Complex, which opened in 2010. Auburn University at Montgomery (AUM) fields teams in NCAA Division II competition. Huntingdon College participates at the NCAA Division III level and Faulkner University is a member of the NAIA and is a nearby rival of AUM. The Blue–Gray Football Classic was an annual college football all-star game held from 1938 until 2001.[92] In 2009, the city played host to the first annual Historical Black College and University (HBCU) All-Star Football Bowl played at Cramton Bowl. Montgomery has also hosted to the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SIAC) football championship and the Camellia Bowl.[93] Montgomery annually hosts the Max Capital City Classic inside Riverwalk Stadium which is a baseball game between rivals Auburn University and the University of Alabama.

Several successful professional athletes hail from Montgomery, including Pro Football Hall of Famer Bart Starr[94] and two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field Alonzo Babers.[95]

Civic organizations

Montgomery has many active governmental and nonprofit civic organizations. City funded organizations include the Montgomery Clean City Commission (a Keep America Beautiful Affiliate) which works to promote cleanliness and environmental awareness. BONDS (Building Our Neighborhoods for Development and Success) which works to engage citizens about city/nonprofit programs, coordinates/assists neighborhood associations, and works to promote neighborhood and civic pride amongst Montgomery residents.

A number of organizations are focused on diversity relations and the city's rich civil rights history. Leadership Montgomery provides citizenship training. Bridge Builders Alabama works with high school youth to promote diversity and civic engagement. The group One Montgomery was founded in 1983 and is a forum for networking of a diverse group of citizens active in civic affairs. Montgomery is also home to The Legacy Museum, Civil Rights Memorial, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Freedom Rides Museum, the National Center for the Study of Civil Rights and African-American Culture, and the Rosa Parks Library and Museum.[96]

Education

Most of the city of Montgomery and Montgomery County are served by the Montgomery Public Schools system.[97] As of 2022, there were 26,381 students enrolled in the system, and 1,412 teachers employed. The system manages 32 elementary schools, 13 middle schools, and 10 high schools as well as 6 magnet schools, 1 alternative school, and 2 special education centers.[98] Montgomery is one of the only cities in Alabama to host three public schools with International Baccalaureate programs. In 2007, Forest Avenue Academic Magnet Elementary School and in 2015, Bear Exploration Center were named a National Blue Ribbon School.[99] In 2022, LAMP High School was named the No. 7 magnet school in the United States and No. 1 public high school in the state of Alabama on U.S. News & World Report's list.[100] Three other Montgomery Public Schools high schools were also on the list, the most of any public school system in the state (Brewbaker Technology Magnet, and George Washington Carver High School).

Maxwell Air Force Base is zoned to Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) schools for grades K-8.[97] The DoDEA operates Maxwell Air Force Base Elementary/Middle School.[101] For high school Maxwell AFB residents are zoned to Montgomery Public Schools facilities: residents of the main base are zoned to Carver High, while residents of the Gunner Annex are zoned to Dr. Percy L. Julian High School. Residents may attend magnet schools.[102]

Montgomery is home to 28 private schools,[103] including notable (former) segregation academies such as Montgomery Academy (Alabama).

The Montgomery City-County Public Library operates eleven public libraries in locations throughout the city and county.

The city is home to Alabama's oldest law library, the Supreme Court and State Law Library, founded in 1828. Located in the Heflin-Torbert Judicial Building, the Law Library owns a rare book collection containing works printed as early as 1605.

Montgomery has been the home of Alabama State University, a historically black university, since the Lincoln Normal University for Teachers relocated from Marion in 1887. Today, ASU is the second largest HBCU in Alabama enrolling nearly 5,000 students from 42 U.S. states and 7 countries.[104] The public Troy University maintains a 3,000 student population campus in downtown Montgomery that houses the Rosa Parks Library and Museum. Another public institution, Auburn University at Montgomery, with an enrollment of nearly 5,000 mostly from the Montgomery area, is in the eastern part of the city.[105] Montgomery's Baptist Medical Center South also hosts a branch of the University of Alabama at Birmingham medical school on its campus on the Eastern Boulevard.

Montgomery also is home to several private colleges: Faulkner University, which has an enrollment of 2,952 (fall 2023), is a Church of Christ-affiliated school which is home to the Thomas Goode Jones School of Law;[106] Huntingdon College, which has a current student population of approximately 1,100 and is affiliated with the United Methodist Church;[107] and Amridge University.

Several two-year colleges have campuses in Montgomery, including H. Councill Trenholm State Technical College[108]

Maxwell Air Force Base is the headquarters for Air University, the United States Air Force's center for professional military education. Branches of Air University based in Montgomery include the Squadron Officer School, the Air Command and Staff College, the Air War College, and the Community College of the Air Force.[109]

Media

The morning newspaper, the Montgomery Advertiser, began publication as The Planter's Gazette in 1829. It is the principal newspaper of central Alabama and is affiliated with the Gannett. In 1970, then publisher Harold E. Martin won the Pulitzer Prize for special reporting while at the Advertiser. The Alabama Journal was a local afternoon paper from 1899 until April 16, 1993, when it published its last issue before merging with the morning Advertiser.

Montgomery is served by seven local television stations: WNCF 32 (ABC), WSFA 12 (NBC), WCOV 20 (Fox), WBMM 22 (CW), WAIQ 26 (PBS), WMCF-TV 45 (TBN), WFRZ-LD 33 (Religious and Educational). In addition, WAKA 8 (CBS), licensed to Selma but operating out of Montgomery, and WBIH 29 (independent) located in Selma, and WIYC 67 (AMV) is licensed to Troy. Montgomery is part of the Montgomery-Selma Designated Market Area (DMA), which is ranked 118th nationally by Nielsen Media Research.[110] Charter Communications and Knology provide cable television service. DirecTV and Dish Network provide direct broadcast satellite television including both local and national channels to area residents.

The Montgomery area is served by eight AM radio stations: WMSP, WMGY, WZKD, WTBF, WGMP, WAPZ, WLWI, and WXVI; and nineteen FM stations: WJSP, WAPR, WELL, WLBF, WTSU, WVAS, WLWI, WXFX, WQKS, WWMG, WVRV, WJWZ, WBAM, WALX, WHHY, WMXS, WHLW, WZHT, and WMRK. Montgomery is ranked 150th largest by Arbitron.[111]

NOAA Weather Radio station KIH55 broadcasts weather and hazard information for Montgomery and vicinity.

Transportation

Two interstate highways run through Montgomery. Interstate 65 is the primary north–south freeway through the city leading between Birmingham and Huntsville to the north and Mobile to the south. Montgomery is the southern terminus of Interstate 85, another north–south freeway (though running east–west in the city), which leads northeast to Atlanta and Charlotte. The major surface street thoroughfare is a loop consisting of State Route 152 in the north, U.S. Highway 231 and U.S. Highway 80 in the east, U.S. Highway 82 in the south, and U.S. Highway 31 along the west of the city. The Alabama Department of Transportation is planning the Outer Montgomery Loop to connect Interstate 85 near Mt. Meigs to U.S. Highway 80 southwest of the city.[112] Upon completion of the loop, it will carry the I-85 designation while the original I-85 into the city center will be redesignated I-685.

Montgomery Area Transit System (The M) provides public transportation with buses serving the city. The system has 32 buses providing an average of 4500 passenger trips daily.[113] The M's ridership has shown steady growth since the system was revamped in 2000; the system served over 1 million passenger trips in 2008.[114] Greyhound Lines operates a terminal in Montgomery for intercity bus travel in the downtown Intermodal Transit Facility.[115]

Montgomery Regional Airport, also known as Dannelly Field, is the major airport serving Montgomery. It serves primarily as an Air National Guard base and for general aviation, but commercial airlines fly to regional connections to Atlanta, Dallas–Fort Worth and Charlotte.[116]

Passenger rail service to Montgomery was enhanced in 1898 with the opening of Union Station. Service continued until 1979, when Amtrak terminated its Floridian route.[117] Amtrak returned from 1989 until 1995 with the Gulf Breeze, an extension of the Crescent line.[118]

According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 84.3% of working city of Montgomery residents commuted by driving alone, 8.8% carpooled, 0.4% used public transportation, and 0.6% walked. About 3.5% used all other forms of transportation, including taxicab, motorcycle, and bicycle. About 5.9% of working city of Montgomery residents worked at home.[119] Despite the high level of commuting by automobile, 8.5% of city of Montgomery households were without a car in 2015, which increased to 11% in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Montgomery averaged 1.62 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[120]

Notable people

Sister city

Montgomery has one sister city:

Pietrasanta, Lucca, Tuscany, Italy[121][122]

Pietrasanta, Lucca, Tuscany, Italy[121][122]

See also

- USS Montgomery, at least 2 ships

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

References

- ^ "City of Montgomery: Capital of Dreams Video". Montgomeryal.gov. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ a b An act to incorporate the town of Montgomery in the county of Montgomery. Archived November 29, 2002, at the Wayback Machine Approved December 3, 1819. Alabama Legislative Acts. Annual Session, Oct – Dec 1819. Pages 110-112. Access Date: January 5, 2014.

- ^ "Municipalities of Alabama Incorporation Dates" (PDF). Alabama League of Municipalities. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 15, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Montgomery, Alabama

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020–2022". United States Census Bureau. March 4, 2024. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Zip Code Lookup". USPS. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Beito, David (May 2, 2009) Something is Rotten in Montgomery Archived June 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, LewRockwell.com

- ^ Montgomery County, Alabama History, Montgomery County, Alabama, archived from the original on February 22, 2007, retrieved January 23, 2009

- ^ Owen, Thomas McAdory; Owen, Marie Bankhead (1921), History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, vol. II (De luxe supplement ed.), Chicago: S. J. Clarke, p. 1037, retrieved January 17, 2009

- ^ a b "Montgomery, Alabama", Goldring / Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, archived from the original on January 21, 2012, retrieved January 31, 2009

- ^ Lewis, Herbert J. (August 31, 2007), "Montgomery County", Encyclopedia of Alabama, archived from the original on June 21, 2010, retrieved January 31, 2009

- ^ Owen, p. 1038

- ^ Neeley, Mary Ann Oglesby (November 6, 2008), "Montgomery", Encyclopedia of Alabama, archived from the original on January 23, 2015, retrieved May 2, 2009

- ^ Brown, Russel K. (1994). To The Manner Born: The Life Of General William H. T. Walker Archived January 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780865549449. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Hébert, Keith S. (October 23, 2007), "Wilson's Raid", Encyclopedia of Alabama, archived from the original on September 22, 2011, retrieved May 2, 2009

- ^ Bailey, Richard (2010). Neither Carpetbaggers nor Scalawags: Black Officeholders During the Reconstruction of Alabama, 1867-1878. NewSouth Books. ISBN 9781588381897.

- ^ Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant tornadoes, 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: Environmental Films. pp. 922–925. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- ^ F. C. Pate (United States Weather Bureau) (October 1946). "The Tornado at Montgomery, Alabama, February 12, 1945". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 27 (8). American Meteorological Society: 462–464. JSTOR 26257954. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Hare, Ken, "Montgomery Bus Boycott: The story of Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights Movement", Montgomery Advertiser, archived from the original on April 1, 2009, retrieved May 2, 2009

- ^ "Honoring Freedom Riders at an Old Bus Station". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 21, 2011. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Dale's Penthouse Fire, gendisasters.com, archived from the original on May 11, 2013, retrieved December 11, 2012

- ^ a b Montgomery Downtown Plan and SmartCode, Dover, Kohl, and Partners, archived from the original on January 13, 2016, retrieved August 23, 2008

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "AirNav: KMGM – Montgomery Regional Airport (Dannelly Field)". Archived from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ RSA Towers, Montgomery, Emporis, Inc., archived from the original on February 29, 2008, retrieved August 23, 2008

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ National Park Service (November 2007), National Historic Landmarks Survey: List of National Historic Landmarks by State (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2007, retrieved August 23, 2008

- ^ "RSA | Dexter Avenue Building". Rsarealestate.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ Nolin, Jill (August 23, 2008), Harriott II's coming, Montgomery Advertiser, archived from the original (Scholar search) on June 28, 2014, retrieved August 23, 2008

- ^ City of Montgomery: Riverfront Facilities, City of Montgomery, archived from the original on September 17, 2008, retrieved August 23, 2008

- ^ Meetings & Groups: New Convention Center, Montgomery Convention and Visitor Bureau, archived from the original on August 20, 2008, retrieved September 21, 2008

- ^ "Montgomery Market District". Montgomery Market District. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Davis, Bethany (January 8, 2014). "New luxury apartments coming to Montgomery's Maxwell Blvd". Apmobile.worldnow.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Campbell Robertson (April 25, 2018). "A Lynching Memorial Is Opening. The Country Has Never Seen Anything Like It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ "History". Alabama State University. Archived from the original on May 4, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c National Register of Historical Places – ALABAMA (AL), Montgomery County, nationalregisterofhistoricalplaces.com, archived from the original on June 10, 2008, retrieved August 23, 2008

- ^ The Campus, Huntingdon College, archived from the original on June 16, 2008, retrieved August 23, 2008

- ^ Montgomery Housing Market Ranks 5th in the U.S., Alabama Real EstateRama, archived from the original on July 15, 2011, retrieved August 26, 2008

- ^ Wright, Carolyn (July 13, 2014). "Early ads boast of fine living in 'Dalriata' neighborhood". Montgomery Advertiser. p. 4D.

- ^ Welcome to Eastdale Mall, Montgomery, Alabama, archived from the original on January 21, 2008, retrieved September 1, 2008

- ^ The Shoppes at EastChase, archived from the original on September 18, 2008, retrieved September 1, 2008

- ^ Montgomery Convention and Visitor Bureau, archived from the original on April 29, 2008, retrieved September 1, 2008

- ^ "Montgomery Advertiser". montgomeryadvertiser.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ "Climatography of the United States No. 20 (1971–2000)" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ "Montgomery Alabama Cold Weather Facts". The National Weather Service. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ "Daily Averages for Montgomery, AL (36104)". The Weather Channel Interactive, Inc. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Montgomery AP, AL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Montgomery Airport, AL". U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1981-2010). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for Montgomery, AL 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Comparative Climatic Data For the United States Through 2018" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 19, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Montgomery city, Alabama". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 7, 2024. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Montgomery city, Alabama". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Montgomery city, Alabama". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ Charles C. Mitchell, History of Alabama Cotton, archived from the original on February 22, 2009, retrieved January 10, 2009

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 784; see line eleven.

Situated in the "Cotton Belt" of Alabama, Montgomery handles 160,000-200,000 bales annually.

- ^ The Role of Metro Areas in the U.S. economy (PDF), U.S. Conference of Mayors, March 1, 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2009, retrieved January 5, 2009

- ^ Montgomery, AL Economy at a Glance, Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 19, 2008, archived from the original on January 5, 2009, retrieved January 5, 2009

- ^ "City of Montgomery 2022 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report". March 4, 2024. p. 112.

- ^ MGM Employers, Montgomery Area Chamber of Commerce, archived from the original on March 5, 2024, retrieved March 4, 2024

- ^ Living Wage Calculation for Montgomery County, Alabama, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, archived from the original on September 25, 2023, retrieved March 4, 2024

- ^ Living Wage Calculation for Alabama, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, archived from the original on November 29, 2023, retrieved March 4, 2024

- ^ Wage and Hour Division: State Minimum Wage Laws, United States Department of Labor, archived from the original on November 27, 2019, retrieved March 4, 2024

- ^ "Steven Reed sworn-in as Montgomery's first black mayor". WFSA. November 12, 2019. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "Steven Reed makes history as Montgomery's first black mayor". October 10, 2019. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "Montgomery homicides were 75 in 2023". waka.com. WAKA. January 1, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "More than 300 People Shot in Montgomery in 2021". December 16, 2021. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Montgomery Reaches 75 Homicides in 2021". December 21, 2021. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Montgomery, AL Crime Rate". Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Recreation, Sports, Culture". Funinmontgomery.com. March 1, 1948. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Museum Collections, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, archived from the original (Scholar search) on October 14, 2006, retrieved September 6, 2008

- ^ About SAC's Gallery – About the Society of Arts & Crafts, archived from the original on July 19, 2008, retrieved September 14, 2008

- ^ About the Zoo-Mann Museum, City of Montgomery, Alabama, archived from the original on September 17, 2008, retrieved September 6, 2008

- ^ The Hank Williams Museum, archived from the original on June 24, 2008, retrieved September 14, 2008

- ^ "Museum of Alabama". Museum.alabama.gov. Archived from the original on August 18, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ "Troy: W. A. Gayle Planetarium". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- ^ About Us, Alabama Shakespeare Festival, archived from the original on June 15, 2008, retrieved September 6, 2008

- ^ A Bit of History, Troy University, archived from the original on July 5, 2008, retrieved September 14, 2008

- ^ Welcome to the Montgomery Symphony Orchestra, archived from the original on September 30, 2008, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ Capri Theatre Montgomery, AL, Capri Community Film Society, archived from the original on September 15, 2008, retrieved September 14, 2008

- ^ American Masters. Hank Williams, PBS, archived from the original on May 26, 2005, retrieved September 1, 2008

- ^ Alabama Music Hall of Fame Tommy Shaw, archived from the original on September 14, 2008, retrieved September 1, 2008

- ^ Milford, Nancy (1970), Zelda: A Biography, New York: Harper & Row, p. 24

- ^ F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum, Montgomery Convention Center and Visitor Bureau, archived from the original on June 9, 2008, retrieved September 14, 2008

- ^ Henry, Susan Copeland, Sidney Lanier (1842–1881), New Georgia Encyclopedia, Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press, archived from the original on February 23, 2009, retrieved September 14, 2008

- ^ Official 2008 NCAA Baseball Records Book (PDF), National Collegiate Athletic Association, January 2008, p. 224, archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2008, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ LPGA.com, archived from the original on May 2, 2008, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ Blue-Gray All-Star Classic Games, College Football Data Warehouse, archived from the original on February 23, 2009, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ McMurphy, Brett (August 19, 2013). "Bowl created for MAC, Sun Belt". ESPN. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ Bart Starr, Pro Football Hall of Fame, archived from the original on December 11, 2007, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ Alonzo Babers Biography and Statistics, Sports-Reference.com, archived from the original on February 21, 2009, retrieved September 2, 2008

- ^ "See and do | Montgomery Alabama | Convention & Visitors Bureau". Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "2020 Census – School District Reference Map: Montgomery County, AL" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022. – Text listing Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine: "Maxwell AFB School District" would mean the Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) since that agency operates the on-base public schools.

- ^ "Montgomery Public Schools". Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "2007 No Child Left Behind – Blue Ribbon Schools: All Public Elementary Schools" (PDF). US Department of Education. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "America's Best High Schools: Magnet Schools List". U.S. News & World Report website. 2022. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ "Home". Department of Defense Education Activity. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Maxwell AFB Community". Department of Defense Education Activity. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Schools K-12 – Montgomery, AL Private Schools". Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "About ASU". Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "About Auburn University at Montgomery". Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ "Faulkner University – Discover Faulnker". November 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "About Huntington College". Archived from the original on October 21, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "About Trenholm State: History". Archived from the original on December 13, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ "USAF Air University". Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "Local Television Market Universe Estimates". nielsenmedia.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ "Arbitron Radio Market Rankings: Spring 2011" (PDF). arbitron.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Senator Richard C. Shelby". Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Montgomery Area Transit System". Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Chart FY 08.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Bus stations and stops in Montgomery, AL". Greyhound Bus Lines. Archived from the original on March 5, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Canceled flights: Continental drops Montgomery routes". Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Floridian". Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Gulf Breeze". Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. December 9, 2014. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ "Montgomery, "Sister City" celebration starting Wednesday", Montgomery Advertiser, April 26, 2009, archived from the original on June 28, 2014, retrieved May 2, 2009

- ^ Montgomery now has a sister city, April 29, 2009, archived from the original on March 7, 2014, retrieved July 23, 2012

Further reading

- L. P. Powell (editor), in Historic Towns of the Southern States, (New York, 1900)

- Jeffry C. Benton (editor) A Sense of Place, Montgomery's Architectural History ( )

- Uriah J, Fields. "The Montgomery Improvement Association." www.MIK-kpp01.stanford.edu. Web. January 17, 2013

- "Our Mission" Archived September 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine . January 17, 2013

- Dunn M. John. "The Montgomery Bus Boycott." The Civil Right Movement. 1998. Book. January 18, 2013

- Hare, Ken. "Overview." Montgomery Advertiser. . 2012. Web. January 17, 2013

- "Browder V. Gayle." Core. www.Core-online.org/history/browdervgayle.htm. Web. January 21, 2013

- Burns, Stewart. "Montgomery Bus Boycott." Encyclopedia of Alabama. www.Encyclopediaofalabama.org. June, 9. 2008. Web. 21, Jan. 2013

- "Montgomery Improvement Association." American History. ABC-CLIO, 2013. Web. January 16, 2013

External links

- Official website

- Montgomery article in the Encyclopedia of Alabama Archived January 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 784.