Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (formerly Southern Cult, Southern Death Cult or Buzzard Cult[1][2]), abbreviated S.E.C.C., is the name given by modern scholars to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture. It coincided with their adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom-level complex social organization from 1200 to 1650 CE.[3][4]

Due to some similarities between S.E.C.C. and contemporary Mesoamerican cultures (i.e., artwork with similar aesthetics or motifs; maize-based agriculture; and the development of sophisticated cities with large pyramidal structures), scholars from the late 1800s to mid-1900s suspected there was a connection between the two locations.[5] [6] One hypothesis was that Meso-Americans enslaved by conquistador Tristán de Luna y Arellano (1510-1573) may have spread artistic and religious elements to North America.[7] However, later research indicates the two cultures have no direct links and that their civilizations developed independently.[8]

History of research

The S.E.C.C. was first defined in 1945 by the archaeologists Antonio Waring and Preston Holder as a series of four lists of traits, which they categorized as the Southeastern (centered) Ceremonial Complex. Their concept was of a complex of a specific cult manifestation that originated with Muskogean-speaking peoples in the southern United States.[9][10]

Since then scholars have expanded the original definition, while using its trait lists as a foundation for critical analysis of the entire concept.

In 1989 scholars proposed a more archaeologically-based definition for the Mississippian artistic tradition. Jon Muller of Southern Illinois University proposes the classification of the complex into five horizons, with each as a discrete tradition defined by the origin of specific motifs and ritual objects, and the specific developments in long-distance exchange and political structures.[11]

Description of S.E.C.C.

Due to the seemingly rapid spread of S.E.C.C. traits, early scholarship described the S.E.C.C. as "a kind of religious revival in the lower Mississippi Valley" and nearby regions.[12] As of 2004, theories suggest that the complex developed from pre-existing beliefs spread over the midwest and southeast by the Hopewell Interaction Sphere from 100 BCE to 500 CE.[4][13]

Other research shows the complex operated as an exchange network. This kind of network may be illustrated by a pair of shell gorgets whose representation is so similar as to suggest that they were made by the same artist. One was found in southeast Missouri and the other found hundreds of miles away in Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma, suggesting the items were used as gifts or exchange across a wide region. Numerous other pairs of extremely similar gorgets serve to link sites across the entire Southeast.[14]

The social organization of the Mississippian culture was based on warfare, which was represented by an array of motifs and symbols in articles made from costly raw materials, such as conches from Florida, copper from the Great Lakes area and Appalachian Mountains, lead from northern Illinois and Iowa, pottery from Tennessee, and stone tools sourced from Kansas, Texas, and southern Illinois.[15] Such objects occur in elite burials, together with war axes, maces, and other weapons. These warrior symbols occur alongside other artifacts, which bear cosmic imagery depicting animals, humans, and legendary creatures. This symbolic imagery bound together warfare, cosmology, and nobility into a coherent whole. Some of these categories of artifacts were used as markers of chiefly office, which varied from one location to another. The term Southeast Ceremonial Complex refers to a complex, highly variable set of religious mechanisms that supported the authority of local chiefs.[16]

Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere horizons

| Horizons | Dates | Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Cult Period | 900 - 1150 | Long-nosed god shell and copper masks, and "square cross" symbol appears |

| Southern Cult Period | 1250 - 1350 | Apogee of the horizon, bi-lobed arrows, striped pole, baton or mace, fringed apron, chunkey player, and ogee appear |

| Attenuated Cult Period | 1350 - 1450 | Trade networks break down; motifs previously on exotic materials begin to appear on pottery and other local products |

| Post Southern Cult Period | 1450 - 1550 | Rise of a large number of regional artistic traditions that manifest distinct stylistic differences |

| Historic Period | 1550 onward | Termination of the ideological traditions, as well as the complex; rise of tribal societies of the European contact period |

With the redefinition of the complex, some scholars have suggested choosing a new name to exemplify the new understanding of the large body of art symbols classified as the S.E.C.C. Participants of a decade-long series of conferences held at Texas State University have proposed the terms "Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere" or "M.I.I.S." and "Mississippian Art and Ceremonial Complex" or "M.A.C.C."

The major expression of the complex developed at the Cahokia site and is known as the Braden Style; it corresponds with the Southern Cult Period horizon defined by Muller. Other regional styles developed as a result of the fusion of ideas borrowed from the Braden Style and pre-existing local expressions of post-Hopewellian traditions.[4][13]

Projected development

Projected development of Mississippian Art and Ceremonial Complex (M.A.C.C.) styles

| Classic Braden Cahokia |

Late Braden Cahokia |

Late Braden | |

| Hemphill Moundville | |||

| Craig A Spiro |

Craig B Spiro |

Craig C Spiro | |

| Hightower Etowah | |||

As the major centers, such as Cahokia, collapsed and the trade networks broke down, the regional styles diverged more from the Braden Style and from each other. During the ensuing centuries, the local traditions diverged into the religious beliefs and cosmologies of the different historic tribes known to exist at the time of European contact.

Cosmology

Most S.E.C.C. imagery focuses on cosmology and the supernatural beings who inhabit the cosmos. The cosmological map encompassed real, knowable locations, whether in this world or the supernatural reality of the Otherworld. S.E.C.C. iconography portrayed the cosmos in three levels. The Above World or Overworld, was the home of the Thunderers, the Sun, Moon, and Morning Star or Red Horn / "He Who Wears Human Heads For Earrings" and represented Order and Stability. The Middle World was the Earth that humans live in. The Beneath World or Under World was a cold, dark place of Chaos that was home to the Underwater Panther and Corn Mother or "Old Woman Who Never Dies".

These three worlds were connected by an axis mundi, usually portrayed as a cedar tree or a striped pole reaching from the Under World to the Over World. Each of the three levels also was believed to have its own sub-levels. Deeply ingrained in the world view was the concept of duality and opposition. The beings of the Upper and Under realms were in constant opposition to each other. Ritual and ceremony were the means by which these powerful forces could be accessed and harnessed.[4]

Motifs

Many common motifs in S.E.C.C. artwork are locative symbols that help determine where the action takes place and where the beings originated:[4][13]

| Motif | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Petaloid Motif |

|

This motif derives its name from its resemblance to flower petals, but it most likely represents feathers. A Petalloid Motif placed around individuals, objects, or supernatural beings denotes its location as "celestial". |

| Quincunx or Cross in Circle Motif | The Cross in Circle Motif is prevalent in most Native American religions. It has solar connotations and usually symbolizes the sacred fire that exists in the Middle World. A Cross in Circle Motif combined with a Petaloid Motif symbolized the Above World. | |

| Swastika in Circle Motif | A Swastika is a variation of the Cross in Circle Motif, symbolizing the creative, generative power of the Underworld. | |

| Forked Eye Surround Motif |

|

Beings wearing the Forked Eye Surround Motif are understood to reside in the Above World. It is derived from the eye markings of the peregrine falcon. |

| Eye Surround Motif |

|

Beings wearing the Eye Surround Motif resided in the Under World. |

| Ogee Motif |

|

The Ogee Motif symbolized portals into the Underworld. It appears frequently on Under World Deities. It may symbolize caves, may be derived from representations of female genitalia, or may represent the dorsal markings of the copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix).[17] |

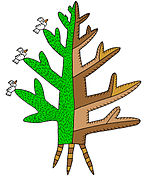

| Striped-Center-Pole Motif |

|

The Cedar Tree and Striped Pole Motif represent the Axis Mundi or "world tree", a central axis on which all the worlds rotated and were connected. It would have had alternating bands of red and white. It is often augmented with raccoon skin bundles, Ogee Motifs, and anthropomorphic heads. |

| Trilobed Motif |

|

The Tri-lobed Motif functioned as a serpent marking and may have symbolized a supernatural's ability to travel from the Lower World to the Upper World. |

| Bi-Lobed Arrow Motif |

|

The Bi-Lobed Arrow Motif is often seen in the headdresses of the warriors/birdmen/chunkey players. A complex symbol, it is a graphic representation of a bow and arrow, an atlatl, or possibly a ceremonial pipe. In the Red Horn Cycle, Red Horn is also called "He who gets hit with deer lungs", which may be a euphemism or an allusion to the fact that deer lungs with the trachea attached, resemble the graphic depiction of the Bi-Lobed Arrow. It may symbolize kinship and adoption rituals related to social hierarchies. Examples in the form of Mississippian copper plates have been found in many Mississippian culture sites. |

| The Hand and Eye Motif |

|

The Hand and Eye Motif is a human hand with an eye gazing out from the palm, yet another symbol of deity. It was one of the most common motifs in Mississippian symbolism and may be related to the Ogee Motif, suggesting it represents a portal to the Otherworld. |

| Mace Motif |

|

The Mace Motif usually is associated with the warrior image and may be combined with other motifs, especially the Cross in Circle Motif. It is a graphic representation of a war club or ceremonial mace, such as the chipped flint and ground stone versions found throughout the southeast. The mace is also closely linked to the Spirit Birds and may even represent the pars pro toto feather of one of these powerful figures.[18] |

| Columnella Pendant Motif |

|

The Columnella Pendant is a graphic representation of the longitudinal center columnella of a whelk shell. Because of the association of whelk shells with the black drink ceremony, it is theorized that this symbol is associated with it as well.[19] |

Birdman

The falcon is one of the most conspicuous symbols of the S.E.C.C. It was simultaneously an avatar of warriors and an object of supplication for a lengthy life, healthy family, and a long line of descendants. Its supernatural origin is placed in the Upper World with a pantheon including the Sun, Moon, and Four Stars. He is most often represented on precious materials, sometimes shell, most often on beaten copper. He dances, costumed with great ground-sweeping wings and a raptor-beaked mask. In his raised right hand he holds a club, prepared to strike. In his left he holds rattles fashioned from human skulls.

At Cahokia, the falcon imagery was elaborated in figural expression. It is associated with warfare, high-stakes gaming, and possibly family dynastic ambitions, symbolized by arrow flights and the rising of the pre-dawn morning star as metaphors for the succession of descendants into the future. Raptor imagery gained prominence during the Hopewell period, but attained its peak in the Braden Style of the early Mississippian period. It survived afterward in the Red Horn mythological cycle and native religion of the Ho-Chunk (Winnebagos), Osage, Ioway, and other plains Siouan peoples. In the Braden Style, the Birdman is divided into four categories.

- Late Braden style Falcon dancer with wings-Mound C, Etowah

- Classic Braden style warrior with wings-Mound C, Etowah

- Club-wielding wingless warrior-Castalian Springs shell engraving

- Chunkey player

- Falcon Dancers with wings.

- Chunkey players / warriors with wings.

- Club-wielding wingless warriors.

- Dancing wingless warriors / chunkey players

Various motifs are associated with the Birdman, including the forked eye motif, columnella pendants, mace or club weapons, severed heads,[20] chunkey play (including chunkey stones, striped and broken chunkey sticks), bellows-shaped aprons, and bi-lobed arrow motifs.[4][13][21]

Red Horn and his sons

The Red Horn Mythic Cycle is from the Ho Chunk, or Winnebago people. The mythic cycle of Red Horn and his sons has certain analogies with the Hero Twins mythic cycle of Mesoamerica.[22] Redhorn was known by many names, including "Morning Star", a reference to his celestial origin, and "He who is Struck with Deer Lungs," a possible reference to the Bi-Lobed Arrow Motif. In the episode associated with this name, Red Horn turns into an arrow to win a race. After winning the race, Redhorn creates heads on his earlobes and makes his hair into a long red braid. Thus he becomes known as "Redhorn" and as "He who has Human Heads as Earlobes".

In another episode, Redhorn and his friends are challenged by the Giants to play ball (or possibly chunkey)[23] with their lives staked on the outcome. The best Giant player was a woman with long red hair identical to Redhorn's. The little heads on Redhorn's ears caused her to laugh so much that it interfered with her game and the Giants lost.[13] The Giants lost all the other contests as well. Then they challenged Redhorn and his friends to a wrestling match in which they threw all but Red Horn's friend Turtle. Since Redhorn and his fellow spirits lost two out of the three matches, they were all slain. The two wives of Redhorn were pregnant at the time of his death. The sons born to each have red hair, with the older one having heads where his earlobes should be, and the younger one having heads in place of his nipples. The older brother discovers where the Giants keep the heads of Redhorn and his friends. The two boys use their powers to steal the heads from the Giants, whom they wipe out almost completely. The boys bring back to life Redhorn, Storms as He Walks, and Turtle. In honor of this feat, Turtle and "Storms as He Walks" promise the boys special weapons.

In another episode, the sons of Redhorn decide to go on the warpath. The older brother asks "Storms as He Walks" for the Thunderbird war bundle. After some effort, it is produced, but the Thunderbirds demand that it have a case. A friend of the sons of Redhorn offers his own body as its case. The boys take the Thunderbird war bundle and with their followers go on a raid to the other side of the sky.[24]

Many S.E.C.C. images seem to be of Red Horn, his companions, and his sons. The characters in the myth seem to be tied integrally to the pipe ceremony, and its association with kinship and adoption.[25] In fact, the Bi-Lobed Arrow Motif may be a graphic depiction of the calumet.[24] Other images found in S.E.C.C. art show figures with long-nosed god maskettes on their ears and in place of their nipples.[4][23][26]

Great Serpent

The Great Serpent (or Horned Serpent) is the most well-known mythological figure from the S.E.C.C. Its roots go back to Hopewell times, if not earlier. It usually is described as horned and winged, although the wings are more an indicator of its celestial origin than an essential form of the creature. In some versions of Shawnee myths, the serpent is described as a multi-headed monster with one green and one red horn, horns being a manifestation or marker of its power. In other myths, it is described as a one-eyed buffalo with one green and one red horn. The Piasa figure of the Miami was painted on a bluff near present-day Alton, Illinois. It was described as having the body of a panther, four legs, a human head, an impossibly long tail and horns.

Mishibizhiw, the Ojibwa underwater panther, was a combination of rattlesnake, cougar, deer, and hawk. Other native peoples also gave descriptions of the being, sometimes now referred to as the Spirit Otter, with the majority seeming to belong to one of two extremes, and a multitude in between.[13]

Distribution of belief

The Great Serpents, the great denizens of the Underworld, were described as powerful beings who were in constant antagonism with the forces of the Upper World, usually represented by the Thunderers (Birdmen or Falcon beings).[4] Although men were to be careful of these beings, they could also be the source of great power. A Shawnee myth tells of the capture and dismemberment of Msi Kinepikwa. The pieces were distributed to the five septs of the tribe, who kept them in their sacred "medicine bundles".[13][27]

Artifacts

S.E.C.C. motifs have been found on a variety of non-perishable materials, including marine shell, ceramics, chert (Duck River cache), carved stone, and copper (Wulfing cache and Etowah plates). Undoubtedly many other materials also were used, but haven't survived the intervening centuries. It may be judged by looking at the remaining artifacts that S.E.C.C. practitioners worked with feathers and designs woven into cloth, practiced body painting, and possibly tattooing, as well as having pierced ears. One surviving painting found on a baked clay floor at the Wickliffe Mounds site suggests they also painted designs in and on their dwellings.[28] Paintings displaying S.E.C.C. imagery also have been found in caves, most notably Mud Glyph Cave in Tennessee. Animal images, serpents, and warrior figures occur, as well as winged warriors, horned snakes, stylized birds, maces, and arrows. Their location underneath the Earth probably reflect aspects of Mississippian myth and cosmology concerning the (perhaps sacred) precincts beneath the earth.[29]

| Motif | Image 1 | Image 2 | Image 3 | Image 4 | Image 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engraved Shell |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ceramics |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stone |

|

|

|

|

|

| Copper |

|

|

|

|

|

Sites

- Alligator Effigy Mound

- Angel Mounds

- Cahokia

- Castalian Springs Mound Site

- Etowah Indian Mounds

- Hiwassee Island

- Kincaid Mounds State Historic Site

- Kolomoki Mounds

- Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park

- Mangum Mound Site

- Moundville Archaeological Site

- Ocmulgee National Monument

- Serpent Mound

- Spiro Mounds

- Town Creek Indian Mound

- Wickliffe Mounds

- Winterville site

References

- ^ Hornerkamp, Nicholas. "Native American Religions Pre-Contact Period". In Hill, Samuel S.; Lippy, Charles H.; Wilson, Charles Reagan (eds.). Encyclopedia of Religion in the South. pp. 542–545.

- ^ Griffin, John Wallace. “Historic Artifacts and the ‘Buzzard Cult’ in Florida.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 4, 1946, pp. 295–301. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30138608. Accessed 3 Mar. 2023.

- ^ muller. "Connections". Archived from the original on 2006-09-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Townsend, Richard F., and Robert V. Sharp, eds. (2004). Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand. The Art Institute of Chicago and Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10601-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krieger, A.D. (1945) "An Inquiry into Supposed Mexican Influences on a Prehistoric 'Cult' In the Southern United States". American Anthropologist, 47: 483-515. doi:10.1525/aa.1945.47.4.02a00020

- ^ Scott Weidensaul (2012). The First Frontier: The Forgotten History of Struggle, Savagery, and Endurance in Early America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 55

- ^ Waring, A. (1945). The De Luna Expedition and Southeastern Ceremonial. American Antiquity, 11(1), 57-58. doi:10.2307/275531

- ^ F. Kent Reilly; James Garber, eds. (2007). Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71347-5.

- ^ Waring, A.J. Jr. (1968). "The Southeastern Cult and Muskogean Ceremonial". In Williams, S. (ed.). The Waring Papers: The Collected Work of Antonio J. Waring. Harvard University. pp. 30–69.

- ^ Waring, A.J. Jr. (1945). "A prehistoric ceremonial complex in the Southeastern United States". American Anthropologist. 47 (1): 1–34. doi:10.1525/aa.1945.47.1.02a00020.

- ^ Muller, Jon (1989). "The Southern Cult". In Galloway, Patricia (ed.). The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, Artifacts and Analysis:The Cottonlandia Conference. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 11–26.

- ^ Nero, Robert W. "Prehistoric Indian Petroglyph." Blue Jay 16.1 (1958).

- ^ a b c d e f g F. Kent Reilly; James Garber, eds. (2007). Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. University of Texas Press. pp. 29–34. ISBN 978-0-292-71347-5.

- ^ Muller. "Connections". Archived from the original on 2006-09-14.

- ^ "Spiro Mounds-A Ceremonial Center of the Southern Cult". Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ "The Late Woodland Period". Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ Sharp, Robert V. (2013), Middle Cumberland Female Effigies and the Portal to the Beneath World, retrieved 2018-01-21

- ^ Butterfield, Valerie (2018). "The Mace and the Spirit Bird: Examining Images and Referents within Mississippian Iconography". Illinois Archaeology. 30: 1–23. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Hudson, Charles M. (1979). Black Drink. University of Georgia Press. pp. 83–112.

- ^ James A. Brown and David H. Dye (2007). The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians. Springer US. ISBN 978-0-387-48300-9.

- ^ Lake Jackson Mounds reveal remnants of thriving culture

- ^ Power, Susan (2004). Early Art of the Southeastern Indians-Feathered Serpents and Winged Beings. University of Georgia Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8203-2501-9.

- ^ a b Pauketat, Timothy R. (2004). Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52066-9.

- ^ a b "The Red Horn Cycle". Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Duncan, James R; Diaz-Granados, Carol (2000). "Of Masks and Myths". Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ Staeck, John P. (1994). "Archaeology, Ethnicity, and Oral Tradition-Chapter 6". Archived from the original on 2009-07-26. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Shawnee Mythology". Archived from the original on 2009-10-27. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ "The Wickliffe Mounds Site". Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Issues in the study of southeastern prehistoric cave art". Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. 2001.