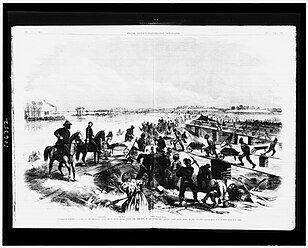

Mississippi Delta levee camps

Levee camps constructed from the early 1800s to the 1930s were originally initiated to create a system of man made levees along the Mississippi river after an increase in flooding. Before 1879 levees were built by a combination of African American convicted criminals, slaves, and racially mixed immigrant laborers. Levee camps underwent racial and sex discrimination throughout their course and helped to construct new identities specifically among black laborers.

Overview

On June 28, 1879 the United States Congress established the Mississippi River Commission in order to address increasing concerns over the navigation and flood control of the Mississippi River. This Commission increased the number of levee camps from Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico to speed up levee construction.[1] This was an attempt to protect riverside populations and prevent overflow in order to maximize land availability along the Mississippi.[2] The levee camp workforce primarily consisted of African American plantation sharecroppers from the Delta area. These workers were used because of their experience with mule driving, work ethic, and the fact that they could be exploited for lower wages.[3] Due to dangerous conditions during flooding, convicted prisoners also continued to build the levees until the early 1900s.

The laborers used mule powered machinery, scrapers, and wheelbarrows to construct the tightly packed slopes of dirt.[1] The levee camp season generally occurred most often from late fall to early winter when the Mississippi water levels were lowest. Approximately one third of the population of the camps consisted of black women, who were employed as cooks or prostitutes for the workers.[3] They also contained livestock including cows, horses, mules, and pigs to run machinery and provide sustenance for the workers.[2] Due to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, control of the camps shifted to the Mississippi Flood Control Act,[4] as government effort was placed more on flood relief.[5]

Levee contractors

Levee contractors ran their camps with strong white supremacist beliefs, using their power to exploit black workers. The contractors publicly beat, whipped, and humiliated the workers in order to strip them of their masculinity and sense of authority. They also encouraged and organized after-hours activities such as gambling, prostitution, and drinking in order to degrade the image and authenticity of the workers and to prevent them from receiving full wages. Many workers had to take out loans with the contractors, which were offered at steep interest rates.[3] The contractors were also purposely inconsistent with their pay periods to force workers to take out more loans at the camp commissaries in order to be able to afford basic necessities.

This discrimination is also evident in the great variation in living and working conditions between workers of different races within the camps. While white workers slept in boarding houses, black workers slept in tents, sometimes very close to livestock.[2] These unsanitary conditions became dangerous for the camp members, who experienced constant outbreaks of life-threatening diseases like malaria and smallpox.[1] Workers went through 12–16 hour work days and were forced to continue no matter the weather conditions, which were brutal during the winter.[2] At an average wage of one to two dollars a day, black workers were paid 1.5 dollars less than the average white worker.[6]

NAACP investigations

Rumors regarding discrimination and the inadequate living conditions caused the NAACP to conduct an investigation on the levee camps. Funded by Katharine Drexel, in December 1932 Roy Wilkins and George Schuyler spent three weeks in the Mississippi levee camps disguised as unskilled workers. Wilkins published an article "Mississippi River Slavery – 1933" in the NAACP Crisis Magazine which described their experiences and concerns for the levee workers.[6] These observations caused the NAACP to stress greater awareness of the exploitation of black laborers in the south, and resulted in a number of US Senate hearings.

References

- ^ a b c Cardon, Nathan (2017). "'Less Than Mayhem': Louisiana's Convict Lease, 1865–1901". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 58 (4): 417–441. JSTOR 26290931.

- ^ a b c d Cowley, John (1991). "Shack Bullies and Levee Contractors: Bluesmen as Ethnographers". Journal of Folklore Research. 28 (2/3): 135–162. JSTOR 3814501.

- ^ a b c McCoyer, Michael (2006). "'Rough Mens' in 'the Toughest Places I Ever Seen': The Construction and Ramifications of Black Masculine Identity in the Mississippi Delta's Levee Camps, 1900–1935". International Labor and Working-Class History. 69 (1). doi:10.1017/s0147547906000044. ISSN 0147-5479.

- ^ Spencer, Robyn (1994). "Contested Terrain: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Struggle to Control Black Labor". The Journal of Negro History. 79 (2): 170–181. doi:10.2307/2717627. JSTOR 2717627.

- ^ Lohof, Bruce A. (1970). "Herbert Hoover, Spokesman of Humane Efficiency: The Mississippi Flood of 1927". American Quarterly. 22 (3): 690–700. doi:10.2307/2711620. JSTOR 271162.

- ^ a b Mizelle, Jr, Richard M. (2013). "Black Levee Camp Workers, The NAACP, And The Mississippi Flood Control Project, 1927–1933". The Journal of African American History. 98 (4): 511–530. doi:10.5323/jafriamerhist.98.4.0511. JSTOR 10.5323/jafriamerhist.98.4.0511.