Medri Bahri

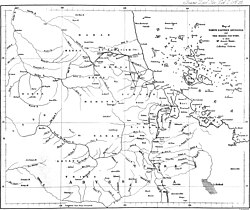

Medri Bahri (Tigrinya: ምድሪ ባሕሪ, English: Land of the Sea) or Mereb Melash (Tigrinya: መረብ ምላሽ, English: Beyond the Mereb), also known as Ma'ikele Bahr or Bahr Melash was a semi-autonomous province of the Ethiopian Empire located north of the Mareb River, in the Eritrean highlands (Kebassa) and some surrounding areas. Mereb Melash corresponds to the administrative territory ruled by the Bahr Negus (King of the Sea) in medieval times. Mereb Melash comprised the historical provinces of Hamasien and Seraye.[1][2][3]

History

According to historian Richard Pankhurst it was during the reign of Emperor Zara Yaqob (r. 1433–1468) when the title Bahr Negash ("Ruler of the sea") appeared for the first time.[4] However, it also appears in an obscure land grant of the Zagwe King Tatadim, who ruled during the 11th century. He considered the unnamed Bahr Negash as one of his seyyuman or "appointed ones".[5][6] Zara Yaqob's chronicle explains how he, after arriving to the region, put much effort into increasing the power of Bahr Negash, placing him above other local chiefs and eventually making him the sovereign of a territory covering the highlands of Hamasien and Seraye.[4][7] His neighbor to the south was the Tigray Mekonnen, master or lord of Tigray. To strengthen the imperial presence in the area, Zara Yaqob also established a military colony consisting of Maya warriors from the south of his realm. These settlers were believed to have the terrified the local population and it was said that the "earth trembled at their arrival" and the inhabitants "fled the country in fear".[4] Near the end of his reign, in 1464/1465, Massawa and the Dahlak archipelago were pillaged by Emperor Zara Yaqob, and the Sultanate of Dahlak was forced to pay tribute to the Ethiopian Empire.[8]

The first European to likely visit Eritrea was the Tuscan traveler Antonio Bartoli, who passed through on his way to Ethiopia in 1402. The map made by Fra Mauro, in completed in 1460, shows already ‘Amasen’ (Hamasien), ‘ S’erana’ (Seraye), and the Tekeze. In the 1520s, Mereb Melash was visited by the Portuguese traveller and priest Francisco Alvares. The current Bahr Negash bore the name Dori and resided in Debarwa, a town on the very northern edge of the highlands. Dori was an uncle of Emperor Lebna Dengel, to whom he paid tribute.[9] These tributes were traditionally paid with horses and imported cloth and carpets.[10] Dori was said to wield considerable power, with his authority extending from the Hamasien highlands to the port of Hirgigo. He was also a promoter of Christianity, generously gifting the churches and monasteries everything they needed.[11] By the time of Alvares' visit, Dori was engaged in warfare against some Nubians after the latter had killed his son. The Nubians were known as robbers and generally had a rather bad reputation.[12] They originated somewhere five to six days away from Debarwa, possibly Taka (a historical province named after Jebel Taka near modern Kassala).[13][14]

During the Ethiopian-Adal War, Mereb Melash was one of the last parts of the empire to be confronted by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi due to its location in the far north. The Bahr Negash Za-Wangel was killed fighting the Adalites in the Battle of Shimbra Kure in 1529. However it wasn’t until 1535 the forces of Imam Ahmad crossed the Mareb river into the region. The Adalite occupation was resisted bitterly by the local population, who killed the Adalite governor Vizer Addole and sent his head to the Emperor. The Emperor upon receiving it had drums beaten and flutes played, optimistically declaring that the fortunates of the war were soon turning. In response, an army led by Wazir Abbas and Abu Bakr Qatin marched into Seraye where they massacred the locals and pacified the region. The Imam's occupation of the coastal highlands resulted in considerable destruction and violence. In 1541 the Portuguese warrior Miguel de Castanhoso arrived in the region, he noted that the lands of the Bahr Negus was "depopulated through fears of the Moors", for "the inhabitants had taken refuge with their herds on a mountain." Many Christians upon seeing the Portuguese came out of their hiding with "crosses in their hands, in solemn procession, praying God for pity." The local monks informed the commander, Cristóvão da Gama, that their enemies had destroyed all their monasteries and churches. They called on de Gama to seek vengeance and many locals joined the Portuguese in their struggles against the Imam, most notably the Bahr Negus Yeshaq.[15][16]

After the death of Imam Ahmad in 1543, Emperor Gelawdewos immediately reestablished imperial suzerainty over the Eritrean highlands. In 1557 the Ottoman Turks conquered the port of Massawa and under Ozdemir Pasha led an expeditionary force inland where they occupied the town of Debarwa. The Turkish troops then built a large fort, but due to the local population's access to firearms, they were forced to retreat back to the coast. Around this time the Bahr Negus Yeshaq, a supporter of Gelawdewos, became very powerful due to the import of firearms through the coast. Although a ruler of a self-governing province, Yeshaq would heavily involve himself in internal Ethiopian affairs. After the death of Gelawdewos he revolted and attempted to place one of his nephews on the throne, but was defeated by Emperor Menas. According to James Bruce, upon being defeated, the Bahr Negash "threw himself at the mercy of the Turks" and ceded Debarwa in exchange for their help.[17][18][10]

Yeshaq and his Turkish allies marched into Tembien to face the army of Sarsa Dengel, however this battle ended in disaster as the Bahr Negus was captured and then executed by the Emperor. Sarsa Dengel then proceeded to march into Debarwa where he captured large quantities of firearms and ordered the destruction of the Turkish fort.[15] This victory was of major importance as put an end to the hopes of the provincial nobility to achieve independence or autonomy from the Ethiopian Empire.[19] Sarsa Dengel, who was greatly angered by Yeshaq's treachery and arrogance, significantly reduced the Bahr Negash's status and the office was temporarily merged with that of the governor of Tigray. However, according to the chronicles of Emperor Susenyos I, during his reign he would revive the old tradition of appointing provincial rulers with the title of the Bahr Negash, appointing one by name of Amda Mikael to rule at least six localities north of the Mareb; Hamasien, Seraye, Akele Guzai, the Debarwa district, the Buri Peninsula, and the "country of the Sahos".[20]

Emperor Fasilides appointed his son-in-law, Hab Sellus of Hamasien, as the governor of a province known as Bambolo-Mellash, which included Mereb Melash and much of Tigray. However, he abused his wife so violently that she died, after which he would make his way to the Emperor's palace in Gondar to seek forgiveness. Upon arriving in the palace he addressed the Emperor, saying "Your Majesty, in your great magnanimity, gave me your daughter and appointed me; but when I wished to approach my wife in accordance with nature and the law she rejected my approach; whereupon I, incited by Satan, raised my hand and struck her; and she died as a result of my blow. Because of this misfortunate I stand before Your Majesty." Fasilides, fearing to alienate the people of Hamasien, decided to forgive his son-in-law, declaring that "You did to her what she deserved". But he significantly reduced his fiefdom to just Mereb Melash. Hab Sellus subsequently returned to Hamasien, and brought the entire region of Mereb Melash under his authority. He would later rule the province for the next 40 years.[21]

In 1692, Iyasu I undertook an expedition in the Mareb river valley, against the "Shanqella of the Dubani" (likely the Kunama or Nara), in present-day Gash Barka. At the sound of the musket fire, the tribesmen were terrified and fled, but were pursued by Iyasu's men who massacred them and sacked their towns.[22] His Royal Chronicle[23] recounts how when the Ottoman Naib of Massawa seized the property of the Emperor's Armenian trade agent, Khoja Murad, and attempted to levy a tax on Iyasu's goods that had landed at Massawa. Iyasu was "greatly angered" and responded with a blockade of that island city until the Naib relented.[24]

In November of 1769, Mereb Mellash was visited by the Scottish traveller James Bruce, who became acquainted with the Bahr Negash while staying in the village of Hadawi (near Segeneiti). He described the unnamed ruler as a "brave, but simple man" and a deputy of Ras Mikael Sehul, but he also considered the land to be a "barbarous and unhappy country." Bruce later revealed that the influence of the Bahr Negash had significantly declined due to the loss of Massawa and Hirgigo to the Turks, stating that it was formerly of great importance; "Before the Abyssinians lost the maritime district of Arkeeko, and the port of Masuah, the office of Baharnagash was one of the most important in the kingdom. It is now nearly a nominal one, under the governor of Tigre." He also reports that the district of Mereb Melash had only been recently incorporated into the province of Tigray by Ras Mikael Sehul with the use of "violence and oppression."[25][26]

The title and position of "Bahr Negash" was not used after the 19th century and provincial governors (for the Seraye, Akele Guzai, and Hamasien) took its place. In turn, the territories north of the Merab began to achieve nominal independence and largely consisted of various local communities ruled by a council of village elders. During much of the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a long-standing rivalry between the rival Hazega and Tsazega villages. Ato Tewoldemedhin of Tsazega constantly fought to reduce his rivals to obedience; his son, Hailu was eventually forced to flee to Gondar to seek the support of Tewodros II. In 1860 he was reinstated as ruler of Hamasien and Seraye, but in Hazega he had to face another strong opponent: Woldemichael Solomon, who was able to seize control of Hamasien by 1868.[27]

Mereb Melash would gain international significance during the reign of Emperor Yohannes IV when it was defended against Egyptian expansionism during the Egyptian–Ethiopian War. In December 1875, a local ruler of the province, Woldemichael Solomon, submitted to the Egyptians at Massawa. This allowed the Egyptians to occupy the entire province with minimal resistance and build a large fort at Gura. However, Ras Alula would defeat the Egyptians at the Battle of Gura, forcing them to withdraw from the province. Following this victory, Ras Alula was declared the governor of Mereb Melash and was authorized to crush the opposition in the province. Alula defeated the followers of Woldemichael Solomon and imprisoned him, but Bahta Hagos evaded capture and allied himself with the Egyptian garrison at Sanhit. In June 1884, the Hewett Treaty was signed, which allowed the Ethiopians to gain free access to Massawa in exchange for the rescue of Egyptian garrisons besieged by the Mahdists. Alula tried to reach the Egyptians at Kassala, but as the Italians landed at Massawa and began their encroachment inland, Alula was forced to abandon this effort. Frustrated and distrustful of the local tribes, Alula allowed his men to massacre the Kunama and Beni-Amer tribes in November 1886. In January 1887, Alula attacked the Italians at Saati, but was beaten back with heavy losses. He subsequently ambushed an Italian battalion sent to reinforce Saati at the Battle of Dogali. In December 1889, Yohannes IV called Alula and his troops up to support him in his fight against the Mahdists, which allowed the Italians to march down from Massawa and seize all of Mereb Melash.[28][29]

Following the death of Yohannes at the Battle of Gallabat, Tigray was completely exhausted from decades of uninterrupted wars. It could no longer challenge the Italians to the north or the Amharas to the south. Menelik II was later recognized as the new emperor, thus cementing Shoan domination over Ethiopia. The loss of Mereb Melash was recognized by Menelik in the Treaty of Wuchale. On the signing of the treaty, Menelik said "The territories north of the Merab Milesh do not belong to Abyssinia nor are under my rule. I am the Emperor of Abyssinia. The land referred to as Eritrea is not peopled by Abyssinians – they are Adals, Bejaa, and Tigres. Abyssinia will defend his territories but will not fight for foreign lands, which Eritrea is to my knowledge."[30]

Notes

- ^ Caulk, Richard Alan (2002). "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447045582.

- ^ G. Marcus, Harold (1994). A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780520925427.

- ^ Abbay, Alemseged (1998). Identity Jilted, Or, Re-imagining Identity?: The Divergent Paths of the Eritrean and Tigrayan Nationalist Struggles. The Red Sea Press. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Pankhurst 1997, p. 101.

- ^ Derat 2020, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Phillipson, David W. (2023). A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780197267870.

- ^ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 54.

- ^ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 160.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 102-104.

- ^ a b Pankhurst 1997, p. 270.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 102-103.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 154-155.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 149-150 & note 14. P. L. Shinnie suggests an origination from the area around Old Dongola, but could this region not be reached from Eritrea within five - six days of travelling time.

- ^ Connel & Killion 2011, p. 96.

- ^ a b Pankhurst 1997, p. 219.

- ^ Frederick A. Edwards (1905). The Conquest of Abyssinia pp.354.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 236.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History Of Ethiopian Towns. p. 68. ISBN 9783515032049.

- ^ Oliver, Ronald (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 546. ISBN 9780521204132.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 395.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 402.

- ^ E. A. Wallis Budge, A History of Ethiopia: Volume II : Nubia and Abyssinia' (London, (Routledge Revivals), 1949), pp. 414. https://books.google.com/books?id=umMtBAAAQBAJ&dq=history%20of%20ethiopia&pg=PA414

- ^ Translated in part by Richard K. P. Pankhurst in The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles. Addis Ababa: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 403.

- ^ Pankhurst 1997, p. 413.

- ^ Bruce, James (1860). Bruce's Travels and Adventures in Abyssinia. p. 73.

- ^ Longrigg, Stephen H. (1945). Short History Of Eritrea. p. 100.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. Steiner. p. 143.

- ^ Erlikh, Haggai (1996). Ras Alula and the Scramble for Africa A Political Biography : Ethiopia & Eritrea, 1875-1897 (PDF). p. 34.

- ^ Caulk, Richard (2002). "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896). Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden. p. 129.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

- Connel, Dan; Killion, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810875050.

- Derat, Marie-Laure (2020). "Before the Solomonids: Crisis, Renaissance and the Emergence of the Zagwe Dynasty (Seventh–Thirteenth Centuries)". In Samantha Kelly (ed.). A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Brill. pp. 31–56.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 9780932415196.

- Tronvoll, Kjetil (1998). Mai Weini, a Highland Village in Eritrea: A Study of the People. Red Sea Press. ISBN 9781569020593.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche.

Further reading

- d'Avray, Anthony (1996). Lords of the Red Sea. The History of a Red Sea Society from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries. Harrassowitz.