Medieval Christian views on Muhammad

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

In contrast to the views of Muhammad in Islam, the Christian views on him stayed highly negative during the Middle Ages for over a millennium.[1][2][3] At this time, Christendom largely viewed Islam as a Christian heresy and Muhammad as a false prophet.[4][5][6][7][8]

Overview

Various Western and Byzantine Christian thinkers[5][6][7][9] considered Muhammad to be a perverted,[5][7] deplorable man,[5][7] a false prophet,[5][6][7][8] and even the Antichrist,[5][6] as he was frequently seen in Christendom as a heretic or possessed by demons.[4][5][6][7][8] Some of them, like Thomas Aquinas, criticized Muhammad's promises of carnal pleasure in the afterlife.[7]

With the Crusades of the High Middle Ages, and the wars against the Ottoman Empire during the Late Middle Ages, the Christian reception of Muhammad became more polemical, moving from the classification as a heretic to depiction of Muhammad as a servant of Satan or as the Antichrist, who will be eternally suffering tortures in Hell amongst the damned.[8] By the Late Middle Ages, Islam was more typically grouped with Paganism, and Muhammad was viewed as an idolater inspired by the Devil.[8] A more relaxed or benign view of Islam only developed in the modern period, after the Islamic empires ceased to be an acute military threat to Europe (see Orientalism).

Early Middle Ages

The earliest written Christian knowledge of Muhammad stems from Byzantine sources, written shortly after Muhammad's death in 632 CE. In the anti-Jewish polemic the Teaching of Jacob, a dialogue between a recent Christian convert and several Jews, one participant writes that his brother "wrote to [him] saying that a deceiving prophet has appeared amidst the Saracens". Another participant in the Doctrina replies about Muhammad: "He is deceiving. For do prophets come with sword and chariot?, …[Y]ou will discover nothing true from the said prophet except human bloodshed".[10] Though Muhammad is never called by his name,[11] the author seems to know of his existence and represents both Jews and Christians as viewing him in a negative light.[12] Other contemporary sources, such as the writings of Sophronius of Jerusalem, do not characterize Saracens as having their own prophet or faith, only remarking that the Saracen attacks must be a punishment for Christian sins.[13]

Sebeos, a 7th-century Armenian bishop and historian, wrote shortly after the end of the first Arab civil war concerning Muhammad and his Farewell Sermon:

I shall discuss the line of the son of Abraham: not the one born of a free woman, but the one born of a serving maid, about whom the quotation from Scripture was fully and truthfully fulfilled: "His hands will be at everyone, and everyone will have their hands at him."[14][15]... In that period a certain one of them, a man of the sons of Ishmael named Muhammad, a merchant, became prominent. A sermon about the Way of Truth, supposedly at God's command, was revealed to them, and [Muhammad] taught them to recognize the God of Abraham, especially since he was informed and knowledgeable about Mosaic history. Because the command had come from On High, he ordered them all to assemble together and to unite in faith. Abandoning the reverence of vain things, they turned toward the living God, who had appeared to their father, Abraham. Muhammad legislated that they were not to eat carrion, not to drink wine, not to speak falsehoods, and not to commit adultery. He said: "God promised that country to Abraham and to his son after him, for eternity. And what had been promised was fulfilled during that time when [God] loved Israel. Now, however, you are the sons of Abraham, and God shall fulfill the promise made to Abraham and his son on you. Only love the God of Abraham, and go and take the country which God gave to your father, Abraham. No one can successfully resist you in war, since God is with you.[16]

Knowledge of Muhammad in Medieval Christendom became available after the early expansion of the Islamic religion in the Middle East and North Africa.[17][18] In the 8th century John of Damascus, a Syrian monk, Christian theologian, and apologist that lived under the Umayyad Caliphate, reported in his heresiological treatise De Haeresibus ("Concerning Heresy") the Islamic denial of Jesus' crucifixion and his alleged substitution on the cross, attributing the origin of these doctrines to Muhammad himself:[19]: 106–107 [20]: 115–116

And the Jews, having themselves violated the Law, wanted to crucify him, but having arrested him they crucified his shadow. But Christ, it is said, was not crucified, nor did he die; for God took him up to himself because of his love for him. And he [Muhammad] says this, that when Christ went up to heaven God questioned him saying "O Jesus, did you say that 'I am Son of God, and God'?" And Jesus, they say, answered: "Be merciful to me, Lord; you know that I did not say so, nor will I boast that I am your servant; but men who have gone astray wrote that I said this and they said lies concerning me and they have been in error". And although there are included in this scripture many more absurdities worthy of laughter, he insists that this was brought down to him by God.[19]: 107 [20]: 115–116

Later, the Latin translation of De Haeresibus, where he explicitly used the phrase "false prophet" in referring to Muhammad, became known in the Christian West.[21][22] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Christian knowledge of Muhammad's life "was nearly always used abusively".[1] Another influential source was the Epistolae Saraceni ("Letters of a Saracen") written by an Oriental Christian and translated into Latin from Arabic.[1] From the 9th century onwards, highly negative biographies of Muhammad were written in Latin.[1] The first two were produced in Spain, the Storia de Mahometh in the 8th or 9th century and the Tultusceptru in the 9th or 10th century. In the latter, Muhammad is presented as a young Christian monk duped by a demon into spreading a false religion.[23] Another Spaniard, Álvaro of Córdoba, proclaimed Muhammad to be the Antichrist in one of his works.[24] Christendom also gained some knowledge of Muhammad through the Mozarabs of Spain, such as the 9th-century Eulogius of Córdoba.[1]

High Middle Ages

In the 11th century Petrus Alphonsi, a Jew who had converted to Christianity, was another Mozarab source of information on Muhammad.[1] Later during the 12th century Peter the Venerable, who saw Muhammad as the precursor to the Antichrist and the successor of Arius,[24] ordered the translation of the Quran into Latin (Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete) and the collection of information on Muhammad so that Islamic teachings could be refuted by Christian scholars.[1]

Muhammad is characterized as "pseudo-prophet" in Byzantine and post-Byzantine religious and historic texts, as for example by Niketas Choniates (12th-13th c.).[26]

Medieval lives of Muhammad

During the 13th century, European biographers completed their work on the life of Muhammad in a series of works by scholars such as Peter Pascual, Riccoldo da Monte di Croce, and Ramon Llull[1] in which Muhammad was depicted as an Antichrist while Islam was shown to be a Christian heresy.[1] The fact that Muhammad was unlettered, that he married a wealthy widow, that in his later life he had several wives, that he was involved in several wars, and that he died like an ordinary person in contrast to the Christian belief in the supernatural end of Jesus' earthly life were all arguments used to discredit Muhammad.[1]

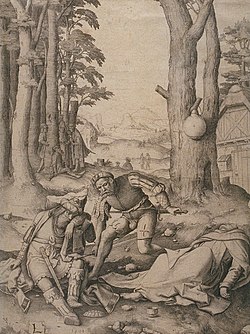

Medieval scholars and churchmen held that Islam was the work of Muhammad who in turn was inspired by Satan. Kenneth Setton wrote that Muhammad was frequently calumniated and made a subject of legends taught by preachers as fact.[27] For example, in order to show that Muhammad was the anti-Christ, it was asserted that Muhammad died not in the year 632 but in the year 666 – the number of the beast – in another variation on the theme the number "666" was also used to represent the period of time Muslims would hold sway of the land.[24] A verbal expression of Christian contempt for Islam was expressed in turning his name from Muhammad to Mahound, the "devil incarnate".[28] Others usually confirmed to pious Christians that Muhammad had come to a bad end.[27] According to one version after falling into a drunken stupor he had been eaten by a herd of swine, and this was ascribed as the reason why Muslims proscribed consumption of alcohol and pork.[27] In another account of the alcohol ban, Muhammad learns about the Bible from a Jew and a heretical Arian monk. Muhammad and the monk get drunk and fall asleep. The Jew kills the monk with Muhammad's sword. He then blames Muhammad, who, believing he has committed the crime in a drunken rage, bans alcohol.[29]

Leggenda di Maometto is another example of such a story. In this version, as a child Muhammad was taught the black arts by a heretical Christian villain who escaped imprisonment by the Christian Church by fleeing to the Arabian Peninsula; as an adult he set up a false religion by selectively choosing and perverting texts from the Bible to create Islam. It also ascribed the Muslim holiday of Friday "dies Veneris" (day of Venus), as against the Jewish (Saturday) and the Christian (Sunday), to his followers' depravity as reflected in their multiplicity of wives.[27] A highly negative depiction of Muhammad as a heretic, false prophet, renegade cardinal or founder of a violent religion also found its way into many other works of European literature, such as the chansons de geste, William Langland's Piers Plowman, and John Lydgate's The Fall of the Princes.[1]

The Golden Legend

The thirteenth century Golden Legend, a best-seller in its day containing a collection of hagiographies, describes "Magometh, Mahumeth (Mahomet, Muhammad)" as "a false prophet and sorcerer", detailing his early life and travels as a merchant through his marriage to the widow, Khadija and goes on to suggest his "visions" came as a result of epileptic seizures and the interventions of a renegade Nestorian monk named Sergius.[30]

Medieval romances

Medieval European literature often referred to Muslims as "infidels" or "pagans", in sobriquets such as the paynim foe. In the same vein, the definition of "Saracen" in Raymond of Penyafort's Summa de Poenitentia starts by describing the Muslims but ends by including every person who is neither a Christian nor a Jew.

These depictions such as those in The Song of Roland represent Muslims worshiping Muhammad (spelt e.g. 'Mahom' and 'Mahumet') as a god, and depict them worshiping various deities in the form of "idols", ranging from Apollyon to Lucifer, but ascribing to them a chief deity known as "Termagant".[24][31]

Depictions of Muhammad in the form of picaresque novel began to appear from the 13th century onward, such as in Alexandre du Pont's Roman de Mahom, the translation of the Mi'raj, the Escala de Mahoma (“The Ladder of Muhammad”) by the court physician of Alfonso X of Castile and León and his son.[1]

In medieval romances such as the French Arthurian cycle, pagans such as the ancient Britons or the inhabitants of "Sarras" before the conversion of King Evelake, who presumably lived well before the birth of Muhammad, are often described as worshipping the same array of gods and as identical to the imagined (Termagant-worshipping) Muslims in every respect. A more positive interpretation appears in the 13th-century Estoire del Saint Grail, the first book in the vast Matter of Britain, the Lancelot-Grail. In describing the travels of Joseph of Arimathea, keeper of the Holy Grail, the author says that most residents of the Middle East were pagans until the coming of Muhammad, who is shown as a true prophet sent by God to bring Christianity to the region. This mission however failed when Muhammad's pride caused him to alter God's wishes, thereby deceiving his followers. Nevertheless, Muhammad's religion is portrayed as being greatly superior to paganism.[32]

The Divine Comedy

In Inferno, the first part of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Muhammad is placed in Malebolge, the eighth circle of hell, designed for those who have committed fraud; specifically, he is placed in the ninth bolgia (ditch) among the sowers of discord and schism. Muhammad is portrayed as split in half, with his entrails hanging out, representing his status as a heresiarch (Inferno 28):

- No barrel, not even one where the hoops and staves go Every which way, was ever split open like a frayed Sinner I saw, ripped from chin to where we fart below.

- His guts hung between his legs and displayed His vital organs, including that wretched sack Which converts to shit whatever gets conveyed down the gullet.

- As I stared at him he looked back And with his hands pulled his chest open, Saying, "See how I split open the crack in myself! See how twisted and broken Mohammed is! Before me walks Ali, his face Cleft from chin to crown, grief–stricken."[33]

This graphic scene is frequently shown in illustrations of the Divine Comedy: Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century fresco Last Judgment by Giovanni da Modena and drawing on Dante, in the San Petronio Basilica in Bologna,[34] as well as in artwork by Salvador Dalí, Auguste Rodin, William Blake, and Gustave Doré.[35]

In his depiction of Muhammad, Dante draws inspiration from medieval Christian views and misconceptions on Muhammad. As stated by historian Karla Mallette, "medieval Christians viewed the historical Muḥammad as a frankly theatrical character."[36] One common allegation laid against Muhammad was that he was an impostor who, in order to satisfy his ambition and his lust, propagated religious teachings that he knew to be false.[37]

Cultural critic and author Edward Said wrote in Orientalism regarding Dante's depiction of Muhammad:

Empirical data about the Orient […] count for very little [i.e., in Dante's work]; what matters and is decisive is […] by no means confined to the professional scholar, but rather the common possession of all who have thought about the Orient in the West […]. What […] Dante tried to do in the Inferno, is […] to characterize the Orient as alien and to incorporate it schematically on a theatrical stage whose audience, manager, and actors are […] only for Europe. Hence the vacillation between the familiar and the alien; Mohammed is always the imposter (familiar, because he pretends to be like the Jesus we know) and always the Oriental (alien, because although he is in some ways "like" Jesus, he is after all not like him).[38]

Dante's representation of Muhammad Inferno 28 is generally interpreted as showing Dante’s disdain for Muslims. However, Dante's relation to Islam is more nuanced than what this canto would suggest. Dante lived during the eighth and ninth Crusades and would have been brought up around the idea that it is righteous to war against Muslims—namely, against the Hafsid dynasty, the Sunni Muslims who ruled the Medieval province Ifriqiya, an area on the northern coast of Africa.[39] It is not surprising that he would have been surrounded by anti-Islam rhetoric and have seen Muslims as the general enemy. For example, he shows his admiration for the crusaders when he writes about his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida in the heavens of Mars in Paradiso.[40] However, this narrative is complicated by Dante's intellectual admiration for some Muslims in Inferno 4, and specifically Averroes, Avicenna, and Saladin.[40]

Later presentations

The depiction of Islam in the Travels of Sir John Mandeville is also relatively positive, though with many inaccurate and mythical features. It is said that Muslims are easily converted to Christianity because their beliefs are already so similar in many ways, and that they believe that only the Christian revelation will last until the end of the world. The moral behaviour of Muslims at the time is shown as superior to that of Christians, and as a standing reproach to Christian society.[41]

When the Knights Templar were being tried for heresy reference was often made to their worship of a demon Baphomet, which was notable by implication for its similarity to the common rendition of Muhammad's name used by Christian writers of the time, Mahomet.[42] All these and other variations on the theme were all set in the "temper of the times" of what was seen as a Muslim-Christian conflict as Medieval Europe was building a concept of "the great enemy" in the wake of the quickfire success of the early Muslim conquests shortly after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, as well as the lack of real information in the West of the mysterious East.[37]

In the Heldenbuch-Prosa, a prose preface to the manuscript Heldenbuch of Diebolt von Hanowe from 1480, the demon Machmet appears to the mother of the Germanic hero Dietrich and builds "Bern" (Verona) in three days.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Muhammad." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 10 January 2007, eb.com article.

- ^ Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511233-4. p.14

- ^ Watt, W. Montgomery (1974). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-881078-4. New Edition, p.231

- ^ a b c d Buhl, F.; Ehlert, Trude; Noth, A.; Schimmel, Annemarie; Welch, A. T. (2012) [1993]. "Muḥammad". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 7. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 360–376. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0780. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Quinn, Frederick (2008). "The Prophet as Antichrist and Arab Lucifer (Early Times to 1600)". The Sum of All Heresies: The Image of Islam in Western Thought. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 17–54. ISBN 978-0195325638.

- ^ a b c d e f g Goddard, Hugh (2000). "The First Age of Christian-Muslim Interaction (c. 830/215)". A History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 34–49. ISBN 978-1-56663-340-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i

Criticism by Christians [...] was voiced soon after the advent of Islam starting with St. John of Damascus in the late seventh century, who wrote of "the false prophet", Muhammad. Rivalry, and often enmity, continued between the European Christian world and the Islamic world [...]. For Christian theologians, the "Other" was the infidel, the Muslim. [...] Theological disputes in Baghdad and Damascus, in the eighth to the tenth century, and in Andalusia up to the fourteenth century led Christian Orthodox and Byzantine theologians and rulers to continue seeing Islam as a threat. In the twelfth century, Peter the Venerable [...] who had the Koran translated into Latin, regarded Islam as a Christian heresy and Muhammad as a sexually self-indulgent and a murderer. [...] However, he called for the conversion, not the extermination, of Muslims. A century later, St. Thomas Aquinas in Summa contra Gentiles accused Muhammad of seducing people by promises of carnal pleasure, uttering truths mingled with many fables and announcing utterly false decisions that had no divine inspiration. Those who followed Muhammad were regarded by Aquinas as brutal, ignorant "beast-like men" and desert wanderers. Through them Muhammad, who asserted he was "sent in the power of arms", forced others to become followers by violence and armed power.

— Michael Curtis, Orientalism and Islam: European Thinkers on Oriental Despotism in the Middle East and India (2009), p. 31, Cambridge University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0521767255. - ^ a b c d e f g h i Hartmann, Heiko (2013). "Wolfram's Islam: The Beliefs of the Muslim Pagans in Parzival and Willehalm". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: Transcultural Experiences in the Premodern World. Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Vol. 14. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 427–442. doi:10.1515/9783110321517.427. ISBN 9783110328783. ISSN 1864-3396.

- ^ John of Damascus, De Haeresibus. See Migne, Patrologia Graeca, Vol. 94, 1864, cols 763–73. An English translation by the Reverend John W. Voorhis appeared in The Moslem World, October 1954, pp. 392–98.

- ^ Walter Emil Kaegi, Jr., "Initial Byzantine Reactions to the Arab Conquest", Church History, Vol. 38, No. 2 (June, 1969), p. 139–149, p. 139–142, quoting from Doctrina Jacobi nuper baptizati 86–87

- ^ Mahomet, among other anglicized forms (such as Mahound), were popular for rendering of the Arabic name Muhammad, borne by the founder of the religion of Islam (died 633). In literary use now superseded by the more correct form Mohammed.

- ^ Kaegi p. 139–149, p. 139–142

- ^ Kaegi p. 139–149, p. 139–141,

- ^ KJV Bible Genesis 16:10–12

- ^ KJV Bible Genesis 17:20

- ^ Bedrosian, Robert (1985). Sebeos' History. New York. pp. Chapter 30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Henry Stubbe An account of the rise and progress of Mahometanism Pg 211

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Edited by Adrian Hastings, Alistair Mason, Hugh Pyper. Pg 330.

- ^ a b Robinson, Neal (1991). "The Crucifixion - Non-Muslim Approaches". Christ in Islam and Christianity: The Representation of Jesus in the Qur'an and the Classical Muslim Commentaries. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 106–140. ISBN 978-0-7914-0558-1. S2CID 169122179.

- ^ a b Schadler, Peter (2017). John of Damascus and Islam: Christian Heresiology and the Intellectual Background to Earliest Christian-Muslim Relations. The History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Vol. 34. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 97–140. doi:10.1163/9789004356054. ISBN 978-90-04-34965-0. LCCN 2017044207. S2CID 165610770.

- ^ "St. John of Damascus: Critique of Islam".

- ^ Source: "The Fountain of Wisdom" (pege gnoseos), part II: "Concerning Heresy" (peri aipeseon)

- ^ Wolf, Kenneth Baxter (2014). "Counterhistory in the Earliest Latin Lives of Muhammad". In Christiane J. Gruber; Avinoam Shalem (eds.). The Image of the Prophet between Ideal and Ideology: A Scholarly Investigation – The Image of the Prophet Between Ideal and Ideology. De Gruyter. pp. 13–26. doi:10.1515/9783110312546.13. ISBN 978-3-11-031238-6.

- ^ a b c d Kenneth Meyer Setton (July 1, 1992). "Western Hostility to Islam and Prophecies of Turkish Doom". Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-87169-201-5. pg 4-15

- ^ Inferno, Canto XXVIII Archived 4 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, lines 22-63; translation by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1867).

- ^ Mai, Angelo (1840). Spicilegium romanum ...: Patrum ecclesiasticorum Serapionis, Ioh. Chrysostomi, Cyrilli Alex., Theodori Mopsuesteni, Procli, Diadochi, Sophronii, Ioh. Monachi, Paulini, Claudii, Petri Damiani scripta varia. Item ex Nicetae Thesauro excerpta, biographi sacri veteres, et Asclepiodoti militare fragmentum. typis Collegii urbani. p. 304.

- ^ a b c d Kenneth Meyer Setton (July 1, 1992). "Western Hostility to Islam and Prophecies of Turkish Doom". Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-87169-201-5. pg 1–5

- ^ Reeves, Minou (2003). Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7564-6., p.3

- ^ Bushkovich, Paul, "Orthodoxy and Islam in Russia", Steindorff, L. (ed) Religion und Integration im Moskauer Russland: Konzepte und Praktiken, Potentiale und Grenzen 14.-17. Jahrhundert, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2010, p.128.

- ^ Voragine, Jacobus de (2012-04-22). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691154077.

- ^ Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, "Termagant

- ^ Lacy, Norris J. (Ed.) (December 1, 1992). Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation, Volume 1 of 5. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-7733-4.

- ^ Seth Zimmerman (2003). The Inferno of Dante Alighieri. iUniverse. p. 191. ISBN 0-595-28090-0.

- ^ Philip Willan (2002-06-24). "Al-Qaida plot to blow up Bologna church fresco". The Guardian.

- ^ Ayesha Akram (2006-02-11). "What's behind Muslim cartoon outrage". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Dante and Islam. Fordham University Press. 2015. ISBN 978-0-8232-6386-8. JSTOR j.ctt9qds84.

- ^ a b Watt, Montgomery, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press, 1961. From p. 229.

- ^ Said, Edward (1979). Orientalism. Vintage Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-394-74067-6.

- ^ Berend, Nora (2020-01-01). "Christians and Muslims in the Middle Ages: From Muhammad to Dante By Michael Frassetto". Journal of Islamic Studies. 33 (1): 111–112. doi:10.1093/jis/etaa040. ISSN 0955-2340.

- ^ a b "The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri". Notes and Queries. s3-XII (290): 59. 1867-07-20. doi:10.1093/nq/s3-xii.290.59c. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ^ The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, CHAPTER XV.

- ^ Mahomet still is the Polish and French word for the English "Muhammad".

Sources

- Di Cesare, Michelina (2012). The Pseudo-historical Image of the Prophet Muhammad in Medieval Latin Literature: A Repertory. De Gruyter.

- Ernst, Carl (2004). Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5577-4.

- Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511233-4.

- Esposito, John (1999). The Islamic Threat: Myth Or Reality?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513076-6.

- Reeves, Minou (2003). Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7564-6.

- Shalem, Avinoam. Constructing the Image of Muhammad in Europe. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and Boston, 2013.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam: An Introduction. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1327-6.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1995). Mystische Dimensionen des Islam. Insel, Frankfurt. ISBN 3-458-33415-7.

- Tolan, John (2002). Saracens: Islam in the European imagination. Columbia University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0231123334.

- Tieszen, Charles (2021). The Christian Encounter with Muhammad: How Theologians have Interpreted the Prophet. Bloomsbury.

- Uebel, Michael (2005). Ecstatic Transformation: On the Uses of Alterity in the Middle Ages. Palgrave, New York. ISBN 978-1403965240.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1961). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-881078-4.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1974). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-881078-4. New Edition.

- William Montgomery Watt, Muslim-Christian Encounters. Perceptions and Misperceptions

- Irving, W. (1868). Mahomet and his successors. New York: Putnam

Encyclopedias

- F. Buhl; A.T. Welch; Annemarie Schimmel; A. Noth; Trude Ehlert (eds.). "Various articles". Encyclopedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica (Rev ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, Incorporated. 2005. ISBN 978-1-59339-236-9.