Media coverage of climate change

Media coverage of climate change has had effects on public opinion on climate change, as it conveys the scientific consensus on climate change that the global temperature has increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.[1]

Climate change communication research shows that coverage has grown and become more accurate.[2]: 11

Some researchers and journalists believe that media coverage of politics of climate change is adequate and fair, while a few feel that it is biased.[3][4][5][6]

History

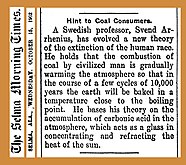

The theory that increases in greenhouse gases would lead to an increase in temperature was first proposed by the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius in 1896, but climate change did not arise as a political issue until the 1990s. It took many years for this particular issue to attract any type of popular attention.[9] In the United States, the mass media devoted little coverage to global warming until the drought of 1988, and James E. Hansen's testimony to the Senate, which explicitly attributed "the abnormally hot weather plaguing our nation" to global warming. Global warming in the U.S. gained more attention after the release of the 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth, featuring Al Gore.[10]

The British press also changed its coverage at the end of 1988, following a speech by Margaret Thatcher to the Royal Society advocating action against human-induced climate change.[11] According to Anabela Carvalho, an academic analyst, Thatcher's "appropriation" of the risks of climate change to promote nuclear power, in the context of the dismantling of the coal industry following the 1984–1985 miners' strike was one reason for the change in public discourse. At the same time environmental organizations and the political opposition were demanding "solutions that contrasted with the government's".[12]

In 2007, the BBC announced the cancellation of a planned television special Planet Relief, which would have highlighted the global warming issue and included a mass electrical switch-off.[13] The editor of BBC's Newsnight current affairs show said: "It is absolutely not the BBC's job to save the planet. I think there are a lot of people who think that, but it must be stopped."[14] Author Mark Lynas said "The only reason why this became an issue is that there is a small but vociferous group of extreme right-wing climate 'sceptics' lobbying against taking action, so the BBC is behaving like a coward and refusing to take a more consistent stance."[15]

A peak in media coverage occurred in early 2007, driven by the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report and Al Gore's documentary An Inconvenient Truth.[16] A subsequent peak in late 2009, which was 50% higher,[17] may have been driven by a combination of the November 2009 Climatic Research Unit email controversy and December 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference.[16][18]

The Media and Climate Change Observatory team at the University of Colorado Boulder found that 2017 "saw media attention to climate change and global warming ebb and flow" with June seeing the maximum global media coverage on both subjects. This rise is "largely attributed to news surrounding United States (US) President Donald J. Trump's withdrawal from the 2015 United Nations (UN) Paris Climate Agreement, with continuing media attention paid to the emergent US isolation following through the G7 summit a few weeks later."[19]

Media coverage of climate change during the Trump Administration remained prominent as most news outlets placed heavy emphasis on Trump-related stories rather than climate-related events.[20] This shift in media focus is referred to as "Trump Dump" and was shown to peak in times when the President was most active on Twitter. Just in the year 2017, the word "Trump" was mentioned 19,187 times in stories covered by five of the nation's biggest press accounts, with "climate" being the second most frequent word.[20]

In a 2020 article, Mark Kaufman of Mashable noted that the English Wikipedia's article on climate change has "hundreds of credible citations" which "counters the stereotype that publicly-policed, collaboratively-edited Wikipedia pages are inherently unreliable".[21]

Common distortions

Factual

Scientists and media scholars who express frustrations with inadequate science reporting argue that it can lead to at least three basic distortions. First, journalists distort reality by making scientific errors. Second, they distort by concentrating on human-interest stories rather than scientific content. And third, journalists distort by rigid adherence to the construct of balanced coverage.[22][23][24][25][26][27][excessive citations] Bord, O'Connor, & Fisher (1998) argue that responsible citizenry necessitates a concrete knowledge of causes and that until, for example, the public understands what causes climate change it cannot be expected to take voluntary action to mitigate its effects.[28]

In 2022 the IPCC reported that "Accurate transference of the climate science has been undermined significantly by climate change countermovements, in both legacy and new/social media environments through misinformation."[2]: 11

A study published in PLOS One in 2024 found that even a single repetition of a claim was sufficient to increase the perceived truth of both climate science-aligned claims and climate change skeptic/denial claims—"highlighting the insidious effect of repetition".[29] This effect was found even among climate science endorsers.[29]

Narrative

According to Shoemaker and Reese, controversy is one of the main variables affecting story choice among news editors, along with human interest, prominence, timeliness, celebrity, and proximity. Coverage of climate change has been accused of falling victim to the journalistic norm of "personalization".[30] W.L Bennet defines this trait as: "the tendency to downplay the big social, economic, or political picture in favor of human trials, tragedies and triumphs".[31] The culture of political journalism has long used the notion of balanced coverage in covering the controversy. In this construct, it is permissible to air a highly partisan opinion, provided this view is accompanied by a competing opinion. But recently scientists and scholars have challenged the legitimacy of this journalistic core value with regard to matters of great importance on which the overwhelming majority of the scientific community has reached a well-substantiated consensus view.

In a survey of 636 articles from four top United States newspapers between 1988 and 2002, two scholars found that most articles gave as much time to the small group of climate change deniers as to the scientific consensus view.[22] Given real consensus among climatologists over global warming, many scientists find the media's desire to portray the topic as a scientific controversy to be a gross distortion. As Stephen Schneider put it:[25]

"a mainstream, well-established consensus may be 'balanced' against the opposing views of a few extremists, and to the uninformed, each position seems equally credible."

Science journalism concerns itself with gathering and evaluating various types of relevant evidence and rigorously checking sources and facts. Boyce Rensberger, the director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Knight Center for Science Journalism, said, "balanced coverage of science does not mean giving equal weight to both sides of an argument. It means apportioning weight according to the balance of evidence."[32]

The claims of scientists also get distorted by the media by a tendency to seek out extreme views, which can result in portrayal of risks well beyond the claims actually being made by scientists.[33] Journalists tend to overemphasize the most extreme outcomes from a range of possibilities reported in scientific articles. A study that tracked press reports about a climate change article in the journal Nature found that "results and conclusions of the study were widely misrepresented, especially in the news media, to make the consequences seem more catastrophic and the timescale shorter".[34]

A 2020 study in PNAS found that newspapers tended to give greater coverage of press releases that opposed action on climate change than those that supported action. The study attributes it to false balance.[35]

Research that was done by Todd Newman, Erik Nisbet, and Matthew Nisbet shows that people's partisan preference is an indicator as to which media outlet they will most likely consume. Most media outlets often align with a particular partisan ideology. This causes people to resort to selective exposure which influences views on world issues such as climate change beliefs.[36]

Since 1990 climate scientists have communicated urgent warnings while simultaneously experiencing the media converting their statements into sensational entertainment.[37]

Alarmism

To achieve climate action

Alarmism is using inflated language, including an urgent tone and imagery of doom.[citation needed] In a report produced for the Institute for Public Policy Research Gill Ereaut and Nat Segnit suggested that alarmist language is frequently used in relation to environmental matters by newspapers, popular magazines and in campaign literature put out by the government and environment groups.[38] It is claimed that when applied to climate change, alarmist language can create a greater sense of urgency.[39]

It has been argued that using sensational and alarming techniques, often evoke "denial, paralysis, or apathy" rather than motivating individuals to action and do not motivate people to become engaged with the issue of climate change.[40][41] In the context of climate refugees—the potential for climate change to displace people—it has been reported that "alarmist hyperbole" is frequently employed by private military contractors and think tanks.[42]

To challenge the science related to global warming

The term alarmist has been used as a pejorative by critics of mainstream climate science to describe those that endorse the scientific consensus without necessarily being unreasonable.[43] MIT meteorologist Kerry Emanuel wrote that labeling someone as an "alarmist" is "a particularly infantile smear considering what is at stake". He continued that using this "inflammatory terminology has a distinctly Orwellian flavor."[44]

Some media reports have used alarmist tactics to challenge the science related to global warming by comparing it with a purported episode of global cooling. In the 1970s, global cooling, a claim with limited scientific support (even during the height of a media frenzy over global cooling, "the possibility of anthropogenic warming dominated the peer-reviewed literature") was widely reported in the press.[45]

Several media pieces have claimed that since the even-at-the-time-poorly-supported theory of global cooling was shown to be false, that the well-supported theory of global warming can also be dismissed. For example, an article in The Hindu by Kapista and Bashkirtsev wrote: "Who remembers today, they query, that in the 1970s, when global temperatures began to dip, many warned that we faced a new ice age? An editorial in The Time magazine on June 24, 1974, quoted concerned scientists as voicing alarm over the atmosphere 'growing gradually cooler for the past three decades', 'the unexpected persistence and thickness of pack ice in the waters around Iceland,' and other harbingers of an ice age that could prove 'catastrophic.' Man was blamed for global cooling as he is blamed today for global warming",[46] and the Irish Independent published an article claiming that "The widespread alarm over global warming is only the latest scare about the environment to come our way since the 1960s. Let's go through some of them. Almost exactly 30 years ago the world was in another panic about climate change. However, it wasn't the thought of global warming that concerned us. It was the fear of its opposite, global cooling. The doom-sayers were wrong in the past and it's entirely possible they're wrong this time as well."[47] Numerous other examples exist.[48][49][50]

Media, politics, and public discourse

As McCombs et al.'s 1972 study of the political function of mass media showed, media coverage of an issue can "play an important part in shaping political reality".[51] Research into media coverage of climate change has demonstrated the significant role of the media in determining climate policy formation.[52] The media has considerable bearing on public opinion, and the way in which issues are reported, or framed, establishes a particular discourse.[53]

Media-policy interface

The relationship between media and politics is reflexive. As Feindt & Oels state, "[media] discourse has material and power effects as well as being the effect of material practices and power relations".[54] Public support of climate change research ultimately decides whether or not funding for the research is made available to scientists and institutions.

Media coverage in the United States during the Bush Administration often emphasized and exaggerated scientific uncertainty over climate change, reflecting the interests of the political elite.[52] Hall et al. suggest that government and corporate officials enjoy privileged access to the media, allowing their line to become the 'primary definer' of an issue.[55] Media sources and their institutions very often have political leanings which determine their reporting on climate change, mirroring the views of a particular party.[56] However, media also has the capacity to challenge political norms and expose corrupt behaviour,[57] as demonstrated in 2007 when The Guardian revealed that American Enterprise Institute received $10,000 from petrochemical giant Exxon Mobil to publish articles undermining the IPCC's 4th assessment report.

Ever-strengthening scientific consensus on climate change means that skepticism is becoming less prevalent in the media (although the email scandal in the build up to Copenhagen reinvigorated climate skepticism in the media[58]).[failed verification]

Discourses of action

Commentators have argued that the climate change discourses constructed in the media have not been conducive to generating the political will for swift action. The polar bear has become a powerful discursive symbol in the fight against climate change. However, such images may create a perception of climate change impacts as geographically distant,[59] and MacNaghten argues that climate change needs to be framed as an issue 'closer to home'.[60] On the other hand, Beck suggests that a major benefit of global media is that it brings distant issues within our consciousness.[61]

Furthermore, media coverage of climate change (particularly in tabloid journalism but also more generally), is concentrated around extreme weather events and projections of catastrophe, creating "a language of imminent terror"[62] which some commentators argue has instilled policy-paralysis and inhibited response. Moser et al. suggest using solution-orientated frames will help inspire action to solve climate change.[63] The predominance of catastrophe frames over solution frames[64] may help explain the apparent value-action gap with climate change; the current discursive setting has generated concern over climate change but not inspired action.

Breaking the prevailing notions in society requires discourse that is traditionally appropriate and approachable to common people. For example, Bill McKibben, an environmental activist, provides one approach to inspiring action: a war-like mobilization, where climate change is the enemy. This approach could resonate with working Americans who normally find themselves occupied with other news headlines.[65]

Compared to what experts know about traditional media's and tabloid journalism's impacts on the formation of public perceptions of climate change and willingness to act, there is comparatively little knowledge of the impacts of social media, including message platforms like Twitter, on public attitudes toward climate change.[66]

In recent years, there has been an increase in the influence and role that social media plays in conveying opinions and knowledge through information sharing. There are several emerging studies that explore the connection between social media and the public's awareness of climate change. Anderson found that there is evidence that social media can raise awareness of climate change issues, but warns that it can also lead to opinion-dominated ideologies and reinforcement.[67] Another study examined datasets from Twitter to assess the ideas and attitudes that users of the application held toward climate change.[68] Williams et al. found that users tend to be active in groups that share the same opinions, often at the extremes of the spectrum, resulting in less polarized opinions between the groups.[68] These studies show that social media can have both a negative and positive impact on the information sharing of issues related to climate change.[67][68]

Youth awareness and activism

Published in the journal Childhood, the article "Children's protest in relation to the climate emergency: A qualitative study on a new form of resistance promoting political and social change" considers how children have evolved into prominent actors to create a global impact on awareness of climate change. It highlights the work of children like Greta Thunberg and the significance of their resistance to the passivity of world leaders regarding climate change. It also discusses how individual resistance can directly be linked to collective resistance and that this then creates a more powerful impact, empowering young people to act more responsibly and take authority over the future. The article discusses the potential impact of youth to raise awareness while also inspiring action, and using social media platforms to share the message.[69]

Threats against climate journalism

The Covering the Planet report, a global survey of more than 740 climate journalists from 102 countries by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network (EJN) and Deakin University, reported that 39% of surveyed journalists were "sometimes or frequently threatened" by their government or from companies or individuals involved in illegal operations that included logging and mining, while the same percentage had to self-censor the content they reported out of fear of repercussions. The report stated that 30% of journalists faced threats of legal action due to their reporting. 62% included statements from sources skeptical of anthropogenic climate change in order to "balance" their reports, some doing so to lower potential scrutiny.[70]

Coverage by country

Australia

Australian news outlets have been reported to present misleading claims and information.[72] One article from The Australian in 2009 claimed that climate change and global warming were fraudulent claims pushed by so-called "warmaholics".[73][non-primary source needed] Many other examples of claims that dismiss climate change have been posted by media outlets in Australia throughout the years following as well.[74][75][76] The 2013 summer and heat wave colloquially known as "Angry Summer" attracted a great deal of media attention, although few outlets directly linked the unprecedented heat to climate change.[77] As the world entered into 2020, global media coverage of climate change issues decreased and COVID-19 coverage increased. In Australia there was a 34% decrease in climate change articles published from March 2020.[78] A 2022 analysis found that Sky News Australia was a major source of climate misinformation globally.[79]

Australia has recently experienced some of the most intense bushfire seasons in its immediate history. This phenomenon has sparked extensive media coverage both nationally and internationally. Much of the media coverage of the 2019 and 2020 Australian bushfire seasons discussed the different factors that lead to and increase the chances of extreme fire seasons.[80] A climate scientist, Nerilie Abram, at Australian National University explained in an article for Scientific American, that the four major conditions need to exist for wildfire and those include "available fuel, dryness of that fuel, weather conditions that aid the rapid spread of fire and an ignition.[81]

Canada

During the Harper government (2006-2015), Canadian media, mostly notably the CBC, made little effort to balance the claims of global warming deniers with voices from science.[82] The Canadian coverage appeared to be driven more by national and international political events rather than the changes to carbon emissions or various other ecological factors.[82] The discourse was dominated by matters of government responsibility, policy-making, policy measures for mitigation, and ways to mitigate climate change; with the issue coverage by mass media outlets continuing to act as an important means of communicating environmental concerns to the general public, rather than introducing new ideas about the topic itself.[82]

Within various provincial and language media outlets, there are varying levels of articulation regarding scientific consensus and the focus on ecological dimensions of climate change.[82] Within Quebec, specifically, these outlets are more likely to position climate change as an international issue, and to link climate change to social justice concerns in order to depict Quebec as a pro-environmental society.[82]

Across various nations, including Canada, there has been an increased effort in the use of celebrities in climate change coverage, which is able to gain audience attention, but in turn, it reinforces individualized rather than structural interpretations of climate change responsibility and solutions.[82]

China

Sweden

Japan

In Japan, a study of newspaper coverage of climate change from January 1998 to July 2007 found coverage increased dramatically from January 2007.[83]

India

A 2010 study of four major, national circulation English-language newspapers in India examined "the frames through which climate change is represented in India", and found that "The results strongly contrast with previous studies from developed countries; by framing climate change along a 'risk-responsibility divide', the Indian national press set up a strongly nationalistic position on climate change that divides the issue along both developmental and postcolonial lines."[84]

On the other hand, a qualitative analysis of some mainstream Indian newspapers (particularly opinion and editorial pieces) during the release of the IPCC 4th Assessment Report and during the Nobel Peace Prize win by Al Gore and the IPCC found that Indian media strongly pursue scientific certainty in their coverage of climate change. This is in contrast to the skepticism displayed by American newspapers at the time. Indian media highlights energy challenges, social progress, public accountability and looming disaster.[85]

Ireland

Ireland has quite a low coverage of climate change in media. A survey created shows how the Irish Times had only 0.84% of news coverage for climate change in the space of 13 years. This percentage is low compared to the rest of Europe. For example- Coverage of climate change in Ireland 10.6 stories, while the rest of Europe lies within 58.4 stories.[86]

New Zealand

A six-month study in 1988 on climate change reporting in the media found that 80% of stories were no worse than slightly inaccurate. However, one story in six contained significant misreporting.[87] Al Gore's film An Inconvenient Truth in conjunction with the Stern Review generated an increase in media interest in 2006.

The popular media in New Zealand often give equal weight to those supporting anthropogenic climate change and those who deny it. This stance is out of step with the findings of the scientific community where the vast majority support the climate change scenarios. A survey carried out in 2007 on climate change gave the following responses:[88]

Not really a problem 8% A problem for the future 13% A problem now 42% An urgent and immediate problem 35% Don't know 2%

Turkey

A study of mainstream media coverage in the late 2010s said that it tended to cover the consequences of climate change rather than mitigation or adaptation.[89]

United Kingdom

The Guardian newspaper is internationally respected for its coverage of climate change.[90]

In the UK, statements by government officials have been influential in the public perception on climate change. In 1988, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher gave one of the first speeches to draw public attention to climate change. This speech highlighted the assumption that industrialization had no impact on the global climate and contrasted it with the stark reality of an increasingly volatile climate. In another speech, Margaret Thatcher expressed that "we have unwittingly begun a massive experiment with the system of the planet itself".[91] Thatcher's speeches on climate change contributed to a record-breaking number of votes for the Green Party in the 1989 European Parliament Election. These speeches sparked an increase in broader media coverage of climate change.[92]

In the early 2000s, David King, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK, stated that the most difficult issue facing the UK was climate change and that its effects were worse than terrorism. David King established that reducing carbon emissions would not only benefit the environment but also the collective wellbeing of UK citizens. King's personal focus was climate change and he produced innovative thinking, tactics and negotiations for the media.[93]

In 1988 in United States, NASA scientist James Hansen stated that climate change was anthropogenic, that is, man-made. This had a similar result to Thatcher's speeches, drawing public attention to the climate crisis and spurring increased media coverage of the issue. The US and UK are comparable in their coverage of climate change for this reason.[94] Despite evidence for anthropogenic climate change arising as early as the late 19th century, both countries lacked significant media coverage on climate change prior to 1988. However, the trajectory of media coverage in these countries varies significantly after this 1988 increase.

For a short period in 1988, the United States had slightly more coverage, but the two countries were quite similar. However, in the following years, the UK consistently produced more articles, and in 2003, it spiked, producing a significantly larger amount of articles. The year 2003 saw the UK and much of Europe experience the hottest summer to date.[95] Temperatures reached up to 38.5 °C, which is 101.3 °F, resulting in 2,000 deaths in the UK, and more across Europe. This significant event drew the attention of newspapers, therefore increasing the amount of articles produced. For example, in the year following the heatwave, The Guardian released an article in March, 2004, warning about even more severe summers that would come. This article included a quote from Dr. Luterbacher, who stated, "We don't know if it will get warmer every year, but the trend is certainly in that direction." The article also claimed that this extreme event was not due to natural causes, suggesting that human activity was responsible.[96] This fear of worse summers on the way and growing understanding of the human causes continued to shows up in increased media coverage after 2003.

In 2001, the National Survey of Public Attitudes to Quality of Life survey found that the public ranked global warming 8th on their list of current concerns. The Office for National Statistics then constructed an additional poll asking the same question but asked about expectations for 20 years ahead. A majority reported that in 20 years time, congestion fumes and noises from traffic would be more concerning than the significant impacts of climate change.[92]

Along with heatwaves, other problems that arise from climate change tend to generate more media coverage. Specifically, the issue of flooding as a result from the changing climate draws attention, and therefore, causes media to report on the issue. In a six year span, between 2001 and 2007, the UK had over a hundred articles per newspaper covering the topic of flooding, showing a clear concern with extreme weather events.[94]

However, although the UK tends to frame climate change as being the fault of humans more than the US, the newspapers often ignore the role that climate change plays in these extreme events. In the hundreds of articles about flooding in the UK between 2001 and 2007, climate change was only mentioned 55 times in any of them. The Guardian had the most mentions of climate change and more consistently drew connections between climate change and issues such as flooding. However, the Guardian still only mentioned climate change 17 times out of 197 stories about climate change.[94] Therefore, while extreme events and tangible effects such as floods or heatwaves do cause more media attention, the media does not always draw connections between these issues and climate change.

Media companies in the United Kingdom produce a diverse range of types of articles regarding climate change, evident when looking at The Guardian, The Observer, The Daily Mail, Mail on Sunday, Sunday Telegraph, The Times and Sunday Times. One scholarly article categorized newspapers from presenting anthropogenic global warming is the only cause of climate change to anthropogenic global warming negligently contributes to climate change. In this study, it is clear that on average, these news sources have increased in scientific credibility.[97]

In 2006 Futerra published research to determine if feedback from the UK community on the topic of global warming was either positive or negative. The results were that only 25 percent of the climate change newspapers were positive. A huge media company that participated in the positive feedback was the Financial Times, which contained the most coverage relating climate change, including a focus on climate change and business opportunities.

The commuters of London, reaching to the amount of a million participants, on the date of October 25, 2007, t provided a free metro newspaper which contained an important article with the headline "We're in the biggest race of our lives." which encompassed the details of the fourth report of the United Nations Environmental Programme's Global Environment Outlook (GEO). The contents of the GEO noted that the actions to address climate change were critically insufficient. A majority of UK citizens were not ready for a change in light of present facts of scientific uncertainty.[93]

The Sunday Telegraph specifically has a history of producing anti-climate change articles and news. The media publication did a major publication of Christopher Monckton, who is well known for his denial of climate change. This stance is reflected in one of their articles:[97][98]

"When this global warming madness passes, future generations will remove this derelict solar and wind infrastructure and return to the only reliable and economical electricity options—coal, gas, hydro and nuclear." (The Sunday Telegraph, London, 2010, 'Officials & climate').[97]

George Monbiot, a weekly column writer for The Guardian, says specifically in Britain that there is a prevalent discourse of unity and collaboration when it comes to environmental concerns in media outlets such as The Guardian, The Times, the Sun and the Independent. He also claims to have read "utter nonsense" in The Daily Mail or The Sunday Telegraph.[98]

A specific case of the community's reaction to climate change can be seen in the YouthStrike4Climate movement, specifically UK Youth Climate Coalition (UKYCC) and the UK Student Climate Network (UKSCN). According to Bart Cammaerts, there has been an overall positive media representation of the climate movement from United Kingdom media outlets. It is significant that 60% of the Daily Mail's articles written about the climate movement were in a negative tone, while the BBC had over 70% written in a positive tone. There are a range of media outlets covering climate change, and they all have different opinions on this movement.[99]

While there are diverse perspectives represented in print media, right-wing newspapers reach far more readers. For example, the right-leaning Daily Mail and The Sun each circulated more than 1 million copies in 2019, while the left-wing equivalents, Daily Mirror and The Guardian only circulated 600,000 copies.[100] Over time, these right-wing newspapers have published fewer editorials opposing climate action. In 2011, the proportion of these editorials was 5:1 against climate change. In 2021, this ratio had dropped to 1:9. Additionally, articles critical of climate action have shifted away from outright denial of climate change. Instead, these editorials highlight the costs associated with climate action, as well as blame other countries for climate change.[101]

In the United Kingdom, the youth activism movement played a key role in the increased production of media coverage of climate change.global activist celebrity and media outlets began covering her more and more. From September 17, 2019, to October 3, 2019, 21% of all media coverage on specific people was about Greta Thunberg. This young climate activist's prevalence in the media continued to increase and thus so did the amount of media on the subject.[99] With more attention to Greta Thunberg and other young women, there has arguably been increased misogyny regarding women in climate change. According to Bart Cammaerts, "These disparaging discourses of belittlement also serve to deny children the right to have a voice on environmentalism and politics."[99]

United States

The way the media report on climate change in English-speaking countries, especially in the United States, has been widely studied, while studies of reporting in other countries have been less expansive.[102][103] A number of studies have shown that particularly in the United States and in the UK tabloid press, the media significantly understated the strength of scientific consensus on climate change established in IPCC Assessment Reports in 1995 and in 2001.

One of the first critical studies of media coverage of climate change in the United States appeared in 1999. The author summarized her research:[6]

Following a review of the decisive role of the media in American politics and of a few earlier studies of media bias, this paper examines media coverage of the greenhouse effect. It does so by comparing two pictures. The first picture emerges from reading all 100 greenhouse-related articles published over a five-month period (May–September 1997) in The Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The Washington Post. The second picture emerges from the mainstream scientific literature. This comparison shows that media coverage of environmental issues suffers from both shallowness and pro-corporate bias.

According to Peter J. Jacques et al., the mainstream news media of the United States is an example of the effectiveness of environmental skepticism as a tactic.[104] A 2005 study reviewed and analyzed the US mass-media coverage of the environmental issue of climate change from 1988 to 2004. The authors confirm that within the journalism industry there is great emphasis on eliminating the presence of media bias. In their study they found that — due to this practice of journalistic objectivity — "Over a 15-year period, a majority (52.7%) of prestige-press articles featured balanced accounts that gave 'roughly equal attention' to the views that humans were contributing to global warming and that exclusively natural fluctuations could explain the earth's temperature increase [...] US mass-media have misrepresented the top climate scientific perspective regarding anthropogenic climate change." As a result, they observed that it is unsurprising for the public to believe that the issue of global warming and the accompanying scientific evidence is still hotly debated.[64]

A study of US newspapers and television news from 1995 to 2006 examined "how and why US media have represented conflict and contentions, despite an emergent consensus view regarding anthropogenic climate science." The IPCC Assessment Reports in 1995 and in 2001 established an increasingly strong scientific consensus, yet the media continued to present the science as contentious. The study noted the influence of Michael Crichton's 2004 novel State of Fear, which "empowered movements across scale, from individual perceptions to the perspectives of US federal powerbrokers regarding human contribution to climate change."[105]

A 2010 study concluded that "Mass media in the U.S. continue to suggest that scientific consensus estimates of global climate disruption, such as those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), are 'exaggerated' and overly pessimistic. By contrast, work on the Asymmetry of Scientific Challenge (ASC) suggests that such consensus assessments are likely to understate climate disruptions [...] new scientific findings were more than twenty times as likely to support the ASC perspective than the usual framing of the issue in the U.S. mass media. The findings indicate that supposed challenges to the scientific consensus on global warming need to be subjected to greater scrutiny, as well as showing that, if reporters wish to discuss "both sides" of the climate issue, the scientifically legitimate 'other side' is that, if anything, global climate disruption may prove to be significantly worse than has been suggested in scientific consensus estimates to date."[106]

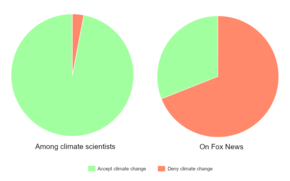

The most watched news network in the United States, Fox News, most of the time promotes climate misinformation and employs tactics that distract from the urgency of global climate change, according to a 2019 study by Public Citizen. According to the study, 86% of Fox News segments that discussed the topic were "dismissive of the climate crisis, cast its consequences in doubt or employed fear mongering when discussing climate solutions". These segments presented global climate change as a political construct, rarely, if ever, discussing the threat posed by climate change or the vast body of scientific evidence for its existence. Consistent with such politicized framing, three messages were most commonly advanced in these segments: global climate change is part of a "big government" agenda of the Democratic Party (34% of segments); an effective response to the climate crisis would destroy the economy and hurtle us back to the Stone Age (26% of segments); and, concern about the climate crisis is "alarmists", "hysterical", the shrill voice of a "doomsday climate cult", or the like (12% of segments). Such segments often featured "experts" who are not climate scientists at all or are personally connected to vested interests, such as the energy industry and its network of lobbyists and think tanks, for example, the Heartland Institute, funded by the Exxon Mobil company and the Koch foundation. The remaining segments (14%) were neutral on the subject or presented information without editorializing.[108]

It has been suggested that the association of climate change with the Arctic in popular media may undermine effective communication of the scientific realities of anthropogenic climate change. The close association of images of Arctic glaciers, ice, and fauna with climate change might harbor cultural connotations that contradict the fragility of the region. For example, in cultural-historical narratives, the Arctic was depicted as an unconquerable, foreboding environment for explorers; in climate change discourse, the same environment is sought to be understood as fragile and easily affected by humanity.[109]

Gallup's annual update on Americans' attitudes toward the environment shows a public that over the last two years (2008-2010) has become less worried about the threat of global warming, less convinced that its effects are already happening, and more likely to believe that scientist themselves are uncertain about its occurrence. In response to one key question, 48% of Americans now believe that the seriousness of global warming is generally exaggerated, up from 41% in 2009 and 31% in 1997, when Gallup first asked the question.[110]

Data from the Media Matters for America organization has shown that, despite 2015 being "a year marked by more landmark actions to address climate change than ever before", the combined climate coverage on the top broadcast networks was down by 5% from 2014.[111][112]

President Donald Trump denies the threat of global warming publicly. As a result of the Trump Presidency, media coverage on climate change was expected to decline during his term as president.[113][needs update]

Globally, media coverage of global warming and climate change decreased in 2020.[78] In the United States, however, newspaper coverage of climate change increased 29% between March 2020 and April 2020, these numbers are still 22% down from coverage in January 2020.[78] This spike in April 2020 can be attributed to the increased coverage of the "Covering Climate Now'' campaign and the US holiday of "Earth Day". The overall decline in climate change coverage in the year 2020 is related to the increased coverage and interconnectedness of COVID-19 and President Trump, without mention of climate change, that began in January 2020.[114]

The U.S. experienced its highest level of climate change media coverage to date in September and October 2021. This increase can be attributed to coverage of the United Nations Conference of Parties meeting which aimed to outline policies to address climate change.[115]

See also

- Climate apocalypse (about usage of the term)

- Climate change and civilizational collapse

- Climate change denial

- Climate Change Denial Disorder, satirical parody film about a fictional disease

- Climate change in popular culture

- Climate crisis (about usage of the term)

- Climate emergency declaration (includes usage of the term "climate emergency")

- Environmental communication

- Environmental skepticism

- Global warming controversy

- Merchants of Doubt

- Requiem for a Species

References

- ^ Antilla, L. (2010). "Self-censorship and science: A geographical review of media coverage of climate tipping points". Public Understanding of Science. 19 (2): 240–256. doi:10.1177/0963662508094099. S2CID 143093512.

- ^ a b "Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change: Technical Summary" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-04-04. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ Newman, Todd P.; Nisbet, Erik C.; Nisbet, Matthew C. (26 September 2018). "Climate change, cultural cognition, and media effects: Worldviews drive news selectivity, biased processing, and polarized attitudes". Public Understanding of Science. 27 (8): 985–1002. doi:10.1177/0963662518801170. PMID 30253695. S2CID 52824926.

- ^ Lichter, S.R.; Rothman (1984). "The media and national defense". National Security Policy: 265–282.

- ^ Bozell, L.B.; Baker, B.H. (1990). "Thats the way it is(n't)". Alexandria, VA.

- ^ a b Nissani, Moti (Sep 1999). "Media Coverage of the Greenhouse Effect". Population and Environment. 21 (1): 27–43. doi:10.1007/BF02436119. S2CID 144096201.

- ^ "Hint to Coal Consumers". The Selma Morning Times. Selma, Alabama, US. October 15, 1902. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

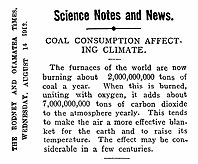

- ^ "Coal Consumption Affecting Climate". Rodney and Otamatea Times, Waitemata and Kaipara Gazette. Warkworth, New Zealand. 14 August 1912. p. 7. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021. Text was earlier published in Popular Mechanics, March 1912, p. 341.

- ^ Bodansky, Daniel (2001). "The History of the Global Climate Change Regime" (PDF). In Luterbacher, Urs; Sprinz, Detlef F. (eds.). International Relations and Global Climate Change. The MIT Press. pp. 23–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ McCright, A. M.; Dunlap R. E. (2000). "Challenging global warming as a social problem: An analysis of the conservative movement's counter-claims" (PDF). Social Problems. 47 (4): 499–522. doi:10.2307/3097132. JSTOR 3097132. See p. 500.

- ^ "Speech to the Royal Society | Margaret Thatcher Foundation". www.margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- ^ Carvalho, Anabela (2007). "Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge" (PDF). Public Understanding of Science. 16 (2): 223–43. doi:10.1177/0963662506066775. hdl:1822/41838. S2CID 220837080.

- ^ Black, Richard (5 September 2007). "BBC switches off climate special". BBC. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ BBC drops climate change special. The Guardian. 5 September 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Michael, Global Warming: Too Hot to Handle for the BBC Archived 15 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 6 September 2007

- ^ a b Boykoff, M. (2010). "Indian media representations of climate change in a threatened journalistic ecosystem" (PDF). Climatic Change. 99 (1): 17–25. Bibcode:2010ClCh...99...17B. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9807-8. S2CID 154624611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ "2004–2010 World Newspaper Coverage of Climate Change or Global Warming". Center for Science and Technology Policy Research. University of Colorado at Boulder. Archived from the original on 2019-08-31. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ STUDY: How Broadcast Networks Covered Climate Change In 2015 Archived 2019-06-13 at the Wayback Machine March 7, 2016 Media Matters for America

- ^ Boykoff, M.; Andrews, K.; Daly, M.; Katzung, J.; Luedecke, G.; Maldonado, C.; Nacu-Schmidt, A. "A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2017". Media and Climate Change Observatory, Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ^ a b "MeCCO Monthly Summaries :: Media and Climate Change Observatory". sciencepolicy.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Kaufman, Mark (2020). "The guardians of Wikipedia's climate change page". Mashable. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ a b Boykoff, M.T.; Boykoff, J.M. (2004). "Balance as bias: Global warming and the US prestige press". Global Environmental Change. 14 (2): 125–136. Bibcode:2004GEC....14..125B. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001.

- ^ Moore, B; Singletary, M. (1985). "Scientific sources' perceptions of network news accuracy". Journalism Quarterly. 62 (4): 816–823. doi:10.1177/107769908506200415. S2CID 144093163.

- ^ Nelkin, D (1995). "Selling science: How the press covers science and technology". New York: W.H. Freeman.

- ^ a b Schneider, S. "Mediarology: The role of citizens, journalists, and scientists in debunking climate change myths". Archived from the original on 2019-10-01. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ^ Singer E, Endreny PM (1993). Reporting on risk: How the mass media portray accidents, diseases, disasters and other hazards. New York: Russell Sage. Archived from the original on 2020-04-14. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ Tankard, J. W.; Ryan, M. (1974). "News source perceptions of accuracy in science coverage". Journalism Quarterly. 51 (2): 219–225. doi:10.1177/107769907405100204. S2CID 145113868.

- ^ Bord, R.J.; O'Connor; Fisher (1998). "Public perceptions of global warming: United States and international perspectives". Climate Research. 11 (1): 75–84. Bibcode:1998ClRes..11...75B. doi:10.3354/cr011075.

- ^ a b Jiang, Yangxueqing; Schwarz, Norbert; Reynolds, Katherine J.; Newman, Eryn J. (7 August 2024). "Repetition increases belief in climate-skeptical claims, even for climate science endorsers". PLOS ONE. 19 (8): See esp. "Abstract" and "General discussion". doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0307294. PMC 11305575. PMID 39110668.

- ^ Shoemaker PJ, Reese SD (1996). Mediating the message: Theories of influence on mass media content. New York: Longman. p. 261.

- ^ W.L Bennet, "News: The Politics of Illusion" 5th edition, (2002). Longman, New York. p.45

- ^ Rensberger, B (2002). "Reporting Science Means Looking for Cautionary Signals". Nieman Reports: 12–14. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ Boykoff, Maxwell T. (2009). "We Speak for the Trees: Media Reporting on the Environment". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 34 (1): 431–457. doi:10.1146/annurev.environ.051308.084254.

- ^ Ladle, R. J.; Jepson, P.; Whittaker, R. J. (2005). "Scientists and the media: the struggle for legitimacy in climate change and conservation science". Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 30 (3): 231–240. Bibcode:2005ISRv...30..231L. doi:10.1179/030801805X42036. S2CID 11994908.

- ^ Wetts, Rachel (2020-07-23). "In climate news, statements from large businesses and opponents of climate action receive heightened visibility". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (32): 19054–19060. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11719054W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921526117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7431090. PMID 32719122.

- ^ Newman, Todd P.; Nisbet, Erik C.; Nisbet, Matthew C. (November 2018). "Climate change, cultural cognition, and media effects: Worldviews drive news selectivity, biased processing, and polarized attitudes". Public Understanding of Science. 27 (8): 985–1002. doi:10.1177/0963662518801170. PMID 30253695. S2CID 52824926.

- ^ Richardson, John H. (20 July 2018). "When the End of Human Civilization Is Your Day Job". Esquire.

- ^ Ereaut, Gill; Segrit, Nat (2006). "Warm Words: How are we Telling the Climate Story and can we Tell it Better?" (PDF). Institute for Public Policy Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-05. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

- ^ Nuccitelli, Dana (July 9, 2018). "There are genuine climate alarmists, but they're not in the same league as deniers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ Lisa Dilling; Susanne C. Moser (2007). "Introduction". Creating a climate for change: communicating climate change and facilitating social change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 978-0-521-86923-2.

- ^ O'Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). ""Fear Won't Do It": Promoting Positive Engagement with Climate Change Through Visual and Iconic Representations". Science Communication. 30 (3): 355–379. doi:10.1177/1075547008329201. S2CID 220752087.

- ^ Hartmann, Betsy (2010). "Rethinking climate refugees and climate conflict: Rhetoric, reality and the politics of policy discourse". Journal of International Development. 22 (2): 233–246. doi:10.1002/jid.1676. ISSN 0954-1748.

- ^ "How climate change alarmists are actually damaging the planet". 2020-07-11. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ^ Emanuel, Kerry (July 19, 2010). ""Climategate": A Different Perspective". National Association of Scholars. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Peterson, Thomas; Connolley, William & Fleck, John (September 2008). "The Myth of the 1970s Global Cooling Scientific Consensus" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 89 (9): 1325–1337. Bibcode:2008BAMS...89.1325P. doi:10.1175/2008BAMS2370.1. S2CID 123635044. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-14.

- ^ Kapitsa, Andrei, and Vladimir Bashkirtsev, "Challenging the basis of Kyoto Protocol", The Hindu, 10 July 2008,

- ^ Irish Independent, "Don't believe doomsayers that insist the world's end is nigh", 16 March 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Schmidt, David, "It's curtains for global warming", Jerusalem Post, 28 June 2002, p. 16B. "If there is one thing more remarkable than the level of alarm inspired by global warming, it is the thin empirical foundations upon which the forecast rests. Throughout the 1970s, the scientific consensus held that the world was entering a period of global cooling, with results equally catastrophic to those now predicted for global warming."

- ^ Wilson, Francis, "The rise of the extreme killers", Sunday Times, 19 April 2009, p. 32. "Throughout history, there have been false alarms: "shadow of the bomb", "nuclear winter", "ice age cometh" and so on. So it's no surprise that today many people are skeptical about climate change. The difference is that we have hard evidence that increasing temperatures will lead to a significant risk of dangerous repercussions."

- ^ National Post, "The sky was supposed to fall: The '70s saw the rise of environmental Chicken Littles of every shape as a technique for motivating public action", 5 April 2000, p. B1. "One of the strange tendencies of modern life, however, has been the institutionalization of scaremongering, the willingness of the mass media and government to lend plausibility to wild surmises about the future. The crucial decade for this odd development was the 1970s. Schneider's book excited a frenzy of glacier hysteria. The most-quoted ice-age alarmist of the 1970s became, in a neat public-relations pivot, one of the most quoted global-warming alarmists of the 1990s."

- ^ McCombs, M; Shaw, D. (1972). "The Agenda Setting Function of Mass Media". Public Opinion Quarterly. 36 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1086/267990. Archived from the original on 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ a b Boykoff, M (2007). "Flogging a Dead Norm? Newspaper Coverage of Anthropogenic Climate Change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003-2006". Area. 39 (2): 000–000, 200. Bibcode:2007Area...39..470B. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00769.x.

- ^ Hajer, M; Versteeg, W (2005). "A Decade of Discourse Analysis of Environmental Politics: Achievements, Challenges, Perspectives". Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 7 (3): 175–184. Bibcode:2005JEPP....7..175H. doi:10.1080/15239080500339646. S2CID 145317648.

- ^ Feindt, P; Oels, A (2005). "Does Discourse Matter? Discourse Analysis in Environmental Policy Making". Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning. 7 (3): 161–173. Bibcode:2005JEPP....7..161F. doi:10.1080/15239080500339638. S2CID 143314592.

- ^ Hall, S; et al. (1978). Policing the Crisis - Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. New York: Holmes and Meier. p. 438.

- ^ Carvalho, A; Burgess, J (December 2005). "Cultural Circuits of Climate Change in UK Broadsheet Newspapers". Risk Analysis. 25 (6): 1457–1469. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.171.178. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00692.x. PMID 16506975. S2CID 2079283.

- ^ Anderson, A (2009). "Media, Politics and Climate Change: Towards a New Research Agenda". Sociology Compass[clarification needed]. 3 (2): 166–182. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00188.x.

- ^ Monibot, George (29 April 2009). "The media laps up fake controversy over climate change". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ^ Lorenzoni, I; Pidgeon (2006). "Public Views on Climate Change: European and USA Perspectives". Climatic Change. 77 (1): 73–95. Bibcode:2006ClCh...77...73L. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9072-z. S2CID 53866794.

- ^ MacNaghten, P (2003). "Embodying the Environment in Everyday Life Practices" (PDF). The Sociological Review. 77 (1).[dead link]

- ^ Beck, U (1992). Risk Society - Towards a New Modernity. Frankfurt: Sage. ISBN 978-0-8039-8345-8.

- ^ Hulme, M (2009). Why We Disagree About Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-521-72732-7.

- ^ Moser & Dilling, M., and L. (2007). Creating a Climate for Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86923-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Boykoff, M; Boykoff, J (November 2007). "Climate Change and Journalistic Norms: A case study of US mass-media coverage" (PDF). Geoforum. 38 (6): 1190–1204. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-01-25. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ^ McKibben, Bill. "We Need to Literally Declare War on Climate Change". The New Republic. The New Republic. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Auer M.; et al. (2014). "The Potential of Microblogs for the Study of Public Perceptions of Climate Change". WIREs Climate Change. 5 (3): 291–296. Bibcode:2014WIRCC...5..291A. doi:10.1002/wcc.273. S2CID 129809371.

- ^ a b Anderson, Ashley A. (2017-03-29). "Effects of Social Media Use on Climate Change Opinion, Knowledge, and Behavior". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.369. ISBN 978-0-19-022862-0. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ a b c Williams, Hywel T.P.; McMurray, James R.; Kurz, Tim; Hugo Lambert, F. (2015-05-01). "Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change". Global Environmental Change. 32: 126–138. Bibcode:2015GEC....32..126W. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006. hdl:10871/17565. ISSN 0959-3780.

- ^ Holmberg, Arita; Alvinius, Aida (2019-10-10). "Children's protest in relation to the climate emergency: A qualitative study on a new form of resistance promoting political and social change". Childhood. 27: 78–92. doi:10.1177/0907568219879970. ISSN 0907-5682.

- ^ Lakhani, Nina; reporter, Nina Lakhani climate justice (2024-06-05). "Nearly half of journalists covering climate crisis globally received threats for their work". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ Leiserowitz, A.; Carman, J.; Buttermore, N.; Wang, X.; et al. (June 2021). International Public Opinion on Climate Change (PDF). New Haven, CT, U.S.: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and Facebook Data for Good. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2021.

- ^ "The Australian says it accepts climate science, so why does it give a platform to 'outright falsehoods'?". The Guardian. 2020-01-14. Archived from the original on 2021-03-06. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ "The warmaholics' fantasy". The Australian. 2009-01-16. Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Bacon, Wendy (2013-10-30). "Sceptical climate part 2: climate science in Australian newspapers". Analysis & Policy Observatory. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ "The Australian Brings You The Climate Science Denial News From Five Years Ago – Graham Readfearn". 10 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Chapman, Simon (16 July 2015). "The Australian's campaign against wind farms continues but the research doesn't stack up". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Aldred, Jessica (2013-03-07). "Australia links 'angry summer' to climate change – at last". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ a b c Nacu-Schmidt, Ami; Pearman, Olivia; Boykoff, Max; Katzung, Jennifer. "Media and Climate Change Observatory Monthly Summary: This historic decline in emissions is happening for all the wrong reasons - Issue 40, April 2020". scholar.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ Readfearn, Graham (2022-06-13). "Sky News Australia is a global hub for climate misinformation, report says". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ "Media reaction: Australia's bushfires and climate change". Carbon Brief. 2020-01-07. Archived from the original on 2020-09-29. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ Abram, Nerilie. "Australia's Angry Summer: This Is What Climate Change Looks Like". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 2021-05-05. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Stoddart, Mark C. J; Haluza-Delay, Randolph; Tindall, David B (2015). "Canadian News Media Coverage of Climate Change: Historical Trajectories, Dominant Frames, and International Comparisons". Society & Natural Resources. 29 (2): 218–232. doi:10.1080/08941920.2015.1054569. S2CID 154437604.

- ^ Sampei Y, Aoyagi-Usui M (2009). "Mass-media coverage, its influence on public awareness of climate-change issues, and implications for Japan's national campaign to reduce greenhouse gas emissions". Global Environmental Change. 19 (2): 203–212. Bibcode:2009GEC....19..203S. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.005.

- ^ Billett, Simon (2010). "Dividing climate change: global warming in the Indian mass media". Climatic Change. 99 (1–2): 1–16. Bibcode:2010ClCh...99....1B. doi:10.1007/s10584-009-9605-3. S2CID 18426714.

- ^ Mittal, Radhika (2012). "Climate Change Coverage in Indian Print Media: A Discourse Analysis". The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses. 3 (2): 219–230. doi:10.18848/1835-7156/CGP/v03i02/37105. hdl:1959.14/181298.

- ^ Robbins, David (November 26, 2015). "Why the media doesn't care about climate change. News likes unambiguous, discrete events, straight-forward, one-off happenings rather than long-term social trends". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ Bell, Allan (1994). "Media (mis)communication on the science of climate change". Public Understanding of Science. 3 (3): 259–275. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/3/3/002. S2CID 145567023.

- ^ ShapeNZ research report. 13 April 2007, New Zealanders' views on climate change and related policy options

- ^ Fide, Ece Baykal (November 2022). "Turkish press climate crisis coverage (2018–2019): elements of disconnect in discourses and the representation of solutions". New Perspectives on Turkey. 67: 32–56. doi:10.1017/npt.2022.8. ISSN 0896-6346. S2CID 248583677.

- ^ "Contemporary Turkey: an ecological account" (PDF). Citizens' Assembly-Turkey (2). January 2019. ISSN 2149-7885. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Boykoff, Maxwell T; Rajan, S Ravi (March 2007). "Signals and noise: Mass-media coverage of climate change in the USA and the UK". EMBO Reports. 8 (3): 207–211. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400924. ISSN 1469-221X. PMC 1808044. PMID 17330062.

- ^ a b Hulme, Mike; Turnpenny, John (2004). "Understanding and Managing Climate Change: The UK Experience". The Geographical Journal. 170 (2): 105–115. Bibcode:2004GeogJ.170..105H. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2004.00112.x. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 3451587.

- ^ a b Shanahan, Mike (2007). Talking about a revolution: climate change and the media (Report). International Institute for Environment and Development.

- ^ a b c Gavin, Neil T.; Leonard-Milsom, Liam; Montgomery, Jessica (May 2011). "Climate change, flooding and the media in Britain". Public Understanding of Science. 20 (3): 422–438. doi:10.1177/0963662509353377. ISSN 0963-6625. PMID 21796885. S2CID 37465809.

- ^ "The heatwave of 2003". Met Office. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Sample, Ian; correspondent, science (2004-03-05). "2003 heatwave a record waiting to be broken". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

{{cite news}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c McAllister, Lucy; Daly, Meaghan; Chandler, Patrick; McNatt, Marisa; Benham, Andrew; Boykoff, Maxwell (August 2021). "Balance as bias, resolute on the retreat? Updates & analyses of newspaper coverage in the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia and Canada over the past 15 years". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (9): 094008. Bibcode:2021ERL....16i4008M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac14eb. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 237158159.

- ^ a b Bird, Helen; Boykoff, Max; Goodman, Mike; Monbiot, George; Littler, Jo (2009-12-01). "The media and climate change". Soundings. 43 (43): 47–64. doi:10.3898/136266209790424595.

- ^ a b c Cammaerts, Bart (2023-05-09). "The mediated circulation of the United Kingdom's YouthStrike4Climate movement's discourses and actions". European Journal of Cultural Studies. 27: 107–128. doi:10.1177/13675494231165645. ISSN 1367-5494. S2CID 258629629.

- ^ Mayhew, Freddy (2019-02-14). "National newspaper ABCs: Mail titles see slower year-on-year circulation decline as bulk sales distortion ends". Press Gazette. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Prater, Josh Gabbatiss, Sylvia Hayes, Joe Goodman and Tom. "Analysis: How UK newspapers changed their minds about climate change". interactive.carbonbrief.org. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lyytimäki J, Tapio P (2009). "Climate change as reported in the press of Finland: From screaming headlines to penetrating background noise". International Journal of Environmental Studies. 66 (6): 723–735. Bibcode:2009IJEnS..66..723L. doi:10.1080/00207230903448490. S2CID 93991183.

- ^ Schmidt, Andreas; Ivanova, Ana; Schäfer, Mike S. (2013). "Media attention for climate change around the world: A comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries". Global Environmental Change. 23 (5): 1233–1248. Bibcode:2013GEC....23.1233S. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.020.

- ^ Environmental skepticism is "a tactic of an elite-driven counter-movement designed to combat environmentalism, and ... the successful use of this tactic has contributed to the weakening of US commitment to environmental protection." — Jacques, P.J.; Dunlap, R.E.; Freeman, M. (June 2008). "The organization of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental skepticism". Environmental Politics. 17 (3): 349–385. Bibcode:2008EnvPo..17..349J. doi:10.1080/09644010802055576. S2CID 144975102.

- ^ Boykoff, M.T. (2007). "From convergence to contention: United States mass media representations of anthropogenic climate change science". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 32 (4): 477–489. Bibcode:2007TrIBG..32..477B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.132.9906. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00270.x.

- ^ Freudenburg WR, Muselli V (2010). "Global warming estimates, media expectations, and the asymmetry of scientific challenge". Global Environmental Change. 20 (3): 483–491. Bibcode:2010GEC....20..483F. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.04.003.

- ^ Dana Nuccitelli (23 October 2013). "Fox News defends global warming false balance by denying the 97% consensus". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Public Citizen, 13 Aug. 2019, "Foxic: Fox News Network's Dangerous Climate Denial 2019: Fox's Continues to Pollute the Airwaves with Misinformation, Give Platform to Deniers" Archived 2020-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stenport, Anna Westerstahl; Vachula, Richard S (2017). "Polar bears and ice: cultural connotations of Arctic environments that contradict the science of climate change". Media, Culture & Society. 39 (2): 282–295. doi:10.1177/0163443716655985. S2CID 148499560.

- ^ Newport, Frank (11 March 2010). "Americans'Global Warming Concerns Continue to Drop: Multiple indicators show less concern, more feelings that global warming is exaggerated". Gallup Poll News Service.

- ^ "How Broadcast Networks Covered Climate Change in 2015". Scribd. Media Matters for America. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- ^ "Study: How Broadcast Networks Covered Climate Change In 2015". Media Matters for America. 2016-02-29. Archived from the original on 2019-06-13. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ^ Park, David J. (March 2018). "United States news media and climate change in the era of US President Trump". Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. 14 (2): 202–204. Bibcode:2018IEAM...14..202P. doi:10.1002/ieam.2011. ISSN 1551-3793. PMID 29193745. S2CID 3779585.

- ^ "Climate change news coverage has declined. The audience has not". Digital Content Next. 2020-09-23. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ "2021 Year End Retrospective, Special Issue 2021, A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2021". sciencepolicy.colorado.edu. MeCCO Monthly Summaries :: Media and Climate Change Observatory. 2021. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

Further reading

- Pooley, Eric (June 8, 2010). The Climate War: True Believers, Power Brokers, and the Fight to Save the Earth. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-1-4013-2326-4.

- Michael Specter (2009). Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives. Penguin Press HC, The. ISBN 978-1-59420-230-8

- Mike Hulme (2009). Why we disagree about climate change: understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-72732-7.

- Tammy Boyce; Lewis, Justin, eds. (2009). Climate Change and the Media (Global Crises and the Media). Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4331-0460-2.

- Uusi-Rauva C, Tienari J (2010). "On the relative nature of adequate measures: Media representations of the EU energy and climate package". Global Environmental Change. 20 (3): 492–501. Bibcode:2010GEC....20..492U. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.03.001.

- Anderson, Alison (March 2009). "Media, Politics and Climate Change: Towards a New Research Agenda". Sociology Compass. 3 (2): 166–182. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00188.x.

- Who Speaks for the Climate?: Making Sense of Media Reporting on Climate Change by Maxwell T. Boykoff, Cambridge University Press; 1 edition (September 30, 2011) ISBN 978-0-521-13305-0