McMichael Canadian Art Collection

Entrance to the main building | |

| |

| Established | 8 July 1965[note 1] |

|---|---|

| Location | 10365 Islington Avenue Vaughan, Ontario, Canada |

| Coordinates | 43°50′27″N 79°37′31″W / 43.840776°N 79.625205°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Visitors | 105,208[note 2][1] |

| Director | Sarah Milroy (Executive Director)[2] |

| Curator | Sarah Milroy (Chief Curator)[3] |

| Architect | Leo Venchiarutti |

| Owner | Government of Ontario |

| Website | mcmichael |

The McMichael Canadian Art Collection (MCAC) is an art museum in Kleinburg, Ontario, Canada. The museum is located on a 40-hectare (100-acre) property in Kleinburg, an unincorporated village in Vaughan. The property includes the museum's 7,900-square-metre (85,000 sq ft) main building, a sculpture garden, walking trails, and a cemetery for six members of the Group of Seven.

The collection dates back to 1955, when Robert and Signe McMichael began to collect works from artists associated to the Group of Seven, exhibiting their works at their home in Kleinburg. In 1965, the McMichaels formally reached an agreement to donate their collection and their Kleinburg property to the Government of Ontario in order to establish an art museum. The institution was opened to the public as the McMichael Conservation Collection of Art in 1966. The museum was formally incorporated into the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in 1972. Although the museum was originally established with an institutional focus on the Group of Seven, the museum's mandate was later expanded to include contemporary Canadian art, and art from indigenous Canadians.

The museum's permanent collection includes over 6,500 works by Canadian artists. In addition to its permanent collections, the institution is also the custodian for the archives of works on paper by Inuit artists based in Kinngait. The museum organizes and hosts a number of travelling art exhibitions, typically focused on Canadian art.

History

In 1951 Robert and Signe McMichael purchased a 10-acre (4.0-hectare) plot of land in Kleinburg, Ontario.[4] A home was subsequently built in 1954, with the McMichaels moving into the property.[5] The McMichaels began acquiring works by artists of the Group of Seven for their personal collection, with the first being a painting by Tom Thomson, acquired for C$250 in 1955.[6] In 1962, the McMichaels acquired Tom Thomson's studio situated outside the Studio Building in Toronto, and relocated it to their property to begin restorations on it.[4] By 1965, the McMichaels' personal collection contained 194 paintings either purchased or donated to them.[7]

The McMichaels began exhibiting their works on their Kleinburg property during the weekends, although growing number of visitors led the McMichaels to consider establishing a public a "shrine" dedicated to the Group of Seven.[5][8] On 18 November 1965, the McMichaels and the Government of Ontario reached an agreement, where the McMichaels would donate the collection, and the property to the government, who would maintain the grounds, and maintain the "spirit of the collection".[5][9] As a part of the agreement, the McMichaels would maintain a degree of curatorial control, occupy two of the five seats in the museum's Board of Trustees, and permission to continue inhabiting the property, and be buried there.[6] The McMichaels continued to reside on the property until museum operations made it no longer possible; with the Government of Ontario providing them a home in Caledon.[6]

In the months after the agreement was made, work was undertaken to re-purpose the property into an art museum, and prepare the exhibits for its collection.[10] The property was formally opened to the public on 8 July 1966 as the McMichael Conservation Collection of Art.[7] Robert McMichael served as the museum's first director, holding the position until resigning in 1981.[11]

In 1968, Group of Seven member A. Y. Jackson suggested that the museum serve as the burial ground for himself, and other members of the group.[8] The proposal was later accepted by the museum, with a cemetery for Group of Seven members prepared on the property of the museum.[8] Shortly before his death, Jackson spent a significant portion of his time painting on the property,[12] and serving as the institution's artist-in-residence.[5]

In 1969, the museum's mandate was amended to expand the scope of the museum's collection and scope to include works of similar nature that reflect the "cultural heritage of Canada"; with approval from Robert McMichael, and the Premier of Ontario, John Robarts.[13] An increase in attendance rates, and its collection led to the institution being formally incorporated as a Crown corporation of Ontario on 30 November 1972, when the McMichael Canadian Art Collection Act received Royal Assent.[9] In 1981, the museum's Board of Governors formally requested the province to amend the institution's governing act, so it is governed only by the 1972 act, and not by the 1965 agreement as well.[14] The following dispute led to Robert McMichael's resignation as the museum's director, and an amendment to the Act in 1982 that named McMichael as the institution's "Founder, Director-Emeritus," and elevated the importance of indigenous Canadian works in its collection.[14]

In the 1990s, the Robert McMichael challenged the Board and the province that it had deviated from its original mandate agreed upon. In McMichael v. Ontario, the court originally ruled that changes to the museum's mandate should not have been permitted.[15] The decision was later overturned in the Court of Appeal for Ontario in 1997; and the Supreme Court of Canada dismissing an appeal to that ruling in 1998.[16] Failing to assert the original agreement through judicial means, the McMichaels successfully lobbied Member of Provincial Parliament Helen Johns to introduce a bill that would reassert it.[16] on 2 November 2000, Bill 112 received Royal Assent, amending the museum's mandate to better reflect the original mandate of showcasing Canadian landscape art, particularly works by the Group of Seven.[16]

After proposals were submitted by the museum's Board of Directors, and the Fenwick family, the closest living relatives to the deceased McMichaels, Bill 118 received Royal Assent in June 2011, expanding the museum's mandate to include contemporary Canadian, and indigenous Canadian artists, in addition to artists associated with the Group of Seven.[17] The 2011 amendment to the governing act of the museum also removed the art advisory committee, and restrictions to the museum's exhibition mandate.[17]

Grounds

The McMichael Canadian Art Collection is situated in Kleinburg, an unincorporated village in Vaughan, Ontario. The grounds of the museum are on a 40-hectare (100-acre) conservation area in the Humber River Valley, which also serves as a floodplain for the area.[18] The landscape itself was partially crafted by the McMichaels, and later the Government of Ontario, to help complement the museum's collection; with the McMichaels planting over 500 cedar trees in the area to help recreate the landscapes typically painted by the Group of Seven.[19]

Buildings located on the grounds include the museum's main building, the Meeting House, Pine Cottage, and Tom Thomson's studio. Pine Cottage houses the institution's art studio.[20] In addition to the structures, the grounds also contains a number of walking trails, a sculpture garden, and the McMichael cemetery.[18] The Ivan Eyre Sculpture Garden, and cemetery is located west of the buildings, with the sculpture garden exhibiting works from its permanent collection, and works on loan to the museum.[21] Six members of the Group of Seven are interred at the McMichael cemetery, including A. J. Casson, Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, and Frederick Varley.[8]

Main building

The museum's main building was designed by Ontario-based architect, Leo Venchiarutti, and was completed in 1954.[6] The museum's main building was expanded several times in 1963, 1967, 1969, and 1972,[6] From 1981 to 1983, the museum's main building was closed to the public for a C$10.4 million renovation;[6] no major work has been done to the building since.[22] The main building is approximately 7,900 square metres (85,000 sq ft).[23] The main building was initially named Tapawingo, allegedly meaning place of joy in either Haida or Ojibwe language.[6]

The building has log and barn-board walls, and field-stone fireplaces in an effort to recreate the "atmosphere" of Canadian landscape art; in addition to a floor-to-glass ceiling windows that provide a view of the Humber River Valley.[5] The main building includes 14 viewing halls, a gift shop, and a restaurant.[5] The Western Canada Gallery in the main building contains a forty-foot-long cedar bench, and red cedar arches, both of which contains images carved by Doug Cranmer.[24] However, the main building does not contain a large loading dock, preventing the institution from exhibiting large-scale installation artworks in the building.[25]

Permanent collection

The McMichael Canadian Art Collection is one of the only art museums whose permanent collection contains works exclusively by Canadian artists.[26] The permanent collection originates from the personal collection started by Robert and Signe McMichael in 1955; who later donated it to the province of Ontario in 1965.[5] At the time the McMichaels donated their collection, it contained 187 works.[27] The museum has since expanded this collection to include 6,500 works as of December 2017.[28][29] The museum's permanent collection is organized into four collection areas, contemporary art, First Nations art, the Group of Seven, and Inuit art.[29]

Although the museum's original mandate placed a focus on Canadian landscape art, and the Group of Seven, it has since expanded to include other Canadian artists, including indigenous Canadians. As of 2011, the museum's mandate is to acquire and preserve works for the collection, by artists who have made a contribution to the development of Canadian art, with a focus on the Group of Seven and their contemporaries and on the indigenous Canadians.[30] In addition to artists associated with the Group of Seven, the museum's permanent collection also contains works from Cornelius Krieghoff, David Milne, and Robert Pilot.[31] In November 2014, the museum was bequeathed 50 paintings from artists based in Quebec. French Canadian artists whose works are in the McMichael's permanent collection include Paul-Émile Borduas, Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté, Marc-Aurèle Fortin, Clarence Gagnon, Rita Letendre, Jean Paul Lemieux, and Jean-Paul Riopelle.[31]

The museum's contemporary collection was formally started in 2011, when the museum's mandate was expanded to include contemporary art,[32] although a number of works in the contemporary collection area were acquired by the institution prior to 2011.[10] Canadian artists featured in the contemporary art collection includes Jack Bush, Colleen Heslin, Sarah Anne Johnson, Terence Koh, and Mary Pratt.[32] The museum also exhibits a number of sculptures within its outdoor sculpture garden, including nine sculptures by Ivan Eyre.[21]

Indigenous Canadian art

The museum was one of the first art museums to include works by indigenous Canadian in its collection.[11] In 1957, the McMichaels purchased their first work by a Haida artist, Bill Reid.[26] The McMichaels' personal collection of Inuit stone carvings, and West Coast First Nations wood carvings, masks, and totem poles were donated to the province as a part of the 1965 agreement.[27] By 1981, approximately 42 per cent of works in the permanent collection were works by indigenous Canadian artists.[26]

A number of indigenous artworks in the museum's collection was acquired between 1982 and 2000, when the museum's mandate was amended to include indigenous Canadian art into its definition of "Canadian cultural heritage".[11] The museum's collection of works by indigenous Canadian was expanded to include contemporary artworks in the 1990s, with the museum establishing its first First Nations curator-in-residence in 1994.[24] In 2000, the museum's mandate was amended again, reverting the museum's focus to the Group of Seven and their contemporaries; resulting in the removal of most indigenous Canadian works from the museum's exhibits.[33] Indigenous Canadian works in the collection remained in storage from 2000 to 2004, when works by indigenous Canadian artists were exhibited in the museum's viewing spaces again.[34] Indigenous Canadian art was reintroduced into the museum's mandate following an amendment to the institution's governing act in 2011.[17]

Library and archives

The museum is also home to a library and archives whose holdings include artist files, books, exhibition catalogues, letters, periodicals, and photographs. The museum's holdings specializes in the Group of Seven and indigenous Canadian art.[35]

The archives includes a number of specialized collections. The Arthur Lismer Collection was bequeathed to the museum by Lismer, and contains a number of documents and works from the 1890s to the late 1960s.[35] The Lismer collection includes over 900 drawings, cartoons and sketches; 1300 original photographs; documents published by Lismer, as well as books.[35] The Norman Hallendy Archives was completed in 2015 contains over 12,000 photographs by Hallendy, as well as audio and video recordings, maps, books, and research files on Inuit culture in southwest Baffin Island.[36]

The archives also houses over 100,000 drawings, prints, and sculptures from the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative Ltd., an artist collective based in Cape Dorset, Nunavut.[37] The collective's works were moved to the McMichael's archive on a long-term loan in 1992, after a fire destroyed the collective's studio building[37] The museum has digitized works produced by the collective from approximately 1959 to 1988.[38]

Selected works

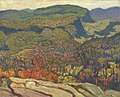

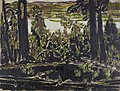

- Homer Watson, Herding Sheep, 1910

- Tom Thomson, In Algonquin Park, Winter 1914–15

- Franklin Carmichael, A Muskoka Road, 1915

- A. Y. Jackson. Cathedral at Ypres, Belgium, 1917

- Frank Johnston. Sunset in the Bush, 1918

- J. E. H. MacDonald, Forest Wilderness, 1921

- Emily Carr, Shoreline, 1936

Notes

- ^ The following date is when the institution was first established as a publicly-managed institution. The institution was opened to the public on 8 July 1966, and was formally incorporated into a crown corporation on 30 November 1972. The institution's permanent collection originates from the private collection of Robert and Signe McMichael, which was started in 1955.

- ^ Total attendance from April 2018 to March 2019.

See also

References

- ^ "Letter from the Executive Director" (PDF). McMichael Canadian Art Collection 2018–19 Annual Report. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2019. p. 4.

- ^ "Board and Staff". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ "Sarah Milroy". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b Knopf 2008, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d e f g "McMichael Canadian Art Collection". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. 4 March 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adams, James (20 November 2015). "The fraught and fierce legacy of the McMichaels' cultural vision". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Our History". McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d Larsen 2009, p. 210.

- ^ a b Knopf 2008, p. 186.

- ^ a b Adams, James (12 August 2016). "McMichael Canadian Art Collection bets big on past for 50th anniversary". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Knopf 2008, p. 159.

- ^ Larsen 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Knopf 2008, p. 164.

- ^ a b Knopf 2008, p. 165.

- ^ Knopf 2008, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Knopf 2008, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Whyte, Murray (3 May 2011). "McMichael Collection: Legal straitjacket to be loosened". Toronto Star. Torstar Corporation.

- ^ a b "Grounds". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ McLoughlin, Moira (1999). Museums and the Representation of Native Canadians: Negotiating the Borders of Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 179. ISBN 0-8153-2988-1.

- ^ "Painting Studio". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Outdoor Art". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "McMichael Canadian Art Collection 2015/16 Business Plan" (PDF). mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ "McGuinty government celebrates 40th anniversary of McMichael Canadian Art Collection". news.ontario.ca. Queen's Printer for Ontario. 17 November 2005. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b Knopf 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Whyte, Murray (11 June 2016). "At the McMichael, an anniversary makes peace with a complicated history". Toronto Star. Torstar Corporation. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Knopf 2008, p. 161.

- ^ a b Knopf 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Hunt, Nigel (26 December 2017). "'The world needs Canadian art. I'm going to give it to them,' says new head of McMichael gallery". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Collection". McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "McMichael Canadian Art Collection Amendment Act, 2011, S.O. 2011, c. 16 - Bill 188". ontario.ca. Queen's Printer of Ontario. 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b Adams, James (14 November 2014). "La belle province takes its place at the McMichael gallery: See 50 works from master Quebec artists". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Contemporary Art". McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ Knopf 2008, p. 171–172.

- ^ Knopf 2008, p. 172.

- ^ a b c "Library & Archives". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ Morita, Linda (2018). "The Norman Hallendy Archives". mcmichael.com. McMichael Canadian Art Collection. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Inuit Art". McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ Allford, Jennifer (26 September 2019). "Exploring south Baffin Island's art, culture and wildlife". Vancouver Sun. Postmedia Network Inc. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

Further reading

- Knopf, Kerstin (2008). Aboriginal Canada Revisited. University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 0-7766-1776-1.

- Larsen, Wayne (2009). A.Y. Jackson: The Life of a Landscape Painter. Dundurn. ISBN 1-7707-0452-3.

- Early Days: Indigenous Art from the McMichael, edited by Bonnie Devine, John Geoghegan and Sarah Milroy. Figure 1 Publishing. 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

External links

- Official website

- Donation of McMichael Collection, 1965, Archives of Ontario YouTube Channel.