Mauritania

Islamic Republic of Mauritania | |

|---|---|

| Motto: شرف، إخاء، عدل "Honour, Fraternity, Justice" | |

| Anthem: النشيد الوطني الموريتاني "National Anthem of Mauritania" | |

Location of Mauritania (in green) in western Africa | |

| Capital and largest city | Nouakchott 18°09′N 15°58′W / 18.150°N 15.967°W |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Other languages | French |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (official) |

| Demonym(s) | Mauritanian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential Islamic republic |

| Mohamed Ould Ghazouani | |

| Mokhtar Ould Djay | |

| Mohamed Ould Meguett | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• Republic established | 28 November 1958 |

• Independence from France | 28 November 1960 |

• Current constitution | 12 July 1991 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,030,000 km2 (400,000 sq mi)[2] (28th) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 4,328,040[3] (128th) |

• Density | 3.4/km2 (8.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2014) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | low (164th) |

| Currency | Ouguiya (MRU) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| ISO 3166 code | MR |

| Internet TLD | .mr |

Mauritania,[a] formally the Islamic Republic of Mauritania,[b] is a sovereign country in Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to the north and northwest, Algeria to the northeast, Mali to the east and southeast, and Senegal to the southwest. By land area Mauritania is the 11th-largest country in Africa and 28th-largest in the world; 90% of its territory is in the Sahara. Most of its population of some 4.3 million lives in the temperate south of the country, with roughly a third concentrated in the capital and largest city, Nouakchott, on the Atlantic coast.

The country's name derives from Mauretania, the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It extended from central present-day Algeria to the Atlantic. Berbers occupied what is now Mauritania by beginning of the third century AD. Groups of Arab tribes migrated to this area in the late seventh century, bringing with them Islam, Arab culture, and the Arabic language. In the early 20th century, Mauritania was colonized by France as part of French West Africa. It achieved independence in 1960, but has since experienced recurrent coups and periods of military dictatorship. The 2008 Mauritanian coup d'état was led by General Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, who won subsequent presidential elections in 2009 and 2014.[8] He was succeeded by General Mohamed Ould Ghazouani following the 2019 elections,[9] head of an autocratic government with a very poor human rights record, particularly because of its perpetuation of slavery; the 2018 Global Slavery Index estimates there are about 90,000 slaves in the country (or 2.1% of the population).[10][11][12]

Despite an abundance of natural resources, including iron ore and petroleum, Mauritania remains poor; its economy is based primarily on agriculture, livestock, and fishing. Mauritania is culturally and politically part of the Arab world; it is a member of the Arab League and Arabic is the official language. The official religion is Islam, and almost all inhabitants are Sunni Muslims. Despite its prevailing Arab identity, Mauritanian society is multiethnic; the Bidhan, or so-called "white moors", make up 30% of the population,[13] while the Haratin, or so-called "black moors", comprise 40%.[13] Both groups reflect a fusion of Arab-Berber ethnicity, language, and culture. The remaining 30% of the population comprises various sub-Saharan ethnic groups.

Etymology

Mauritania takes its name from the ancient Berber kingdom that flourished beginning in the third century BC and later became the Roman province of Mauretania, which flourished into the seventh century AD. The two territories do not overlap, though; historical Mauretania was considerably farther north than modern Mauritania, as it was spread out along the entire western half of the Mediterranean coast of Africa. The term "Mauretania", in turn, derives from the Greek and Roman exonym for the Berber peoples of the kingdom, the Mauri people. The word "Mauri" is also the root of the name for the Moors.[14]

It was more commonly known to Arab geographers as Bilad Chinqit, "the land of the Chinguetti".[15] The term "Mauritanie occidentale" was officially used in a ministerial circular in 1899, based on a proposal by Xavier Coppolani, a French military and colonial leader, who was instrumental in the colonial occupation and creation of modern-day Mauritania. This term, employed by the French, gradually replaced other designations previously used for referring to the country.[16][17]

History

Early history

The ancient tribes of Mauritania were Berber, Niger-Congo,[18] and Bafour peoples. The Bafour were among the first Saharan peoples to abandon their previously nomadic lifestyle and adopt a primarily agricultural one. In response to the gradual desiccation of the Sahara, they eventually migrated southward.[19] Many of the Berber tribes have claimed to have Yemeni (and sometimes other Arab) origins. Little evidence supports those claims, although a 2000 DNA study of the Yemeni people suggested some ancient connection might exist between the peoples.[20]

The Umayyads were the first Arab Muslims to enter Mauritania. During the Islamic conquests, they made incursions into Mauritania and were present in the region by the end of the seventh century.[21] Many Berber tribes in Mauritania fled the arrival of the Arabs to the Gao region in Mali.[21]

Other peoples also migrated south past the Sahara and into West Africa. In the 11th century, several nomadic Berber confederations in the desert regions overlapping present-day Mauritania joined together to form the Almoravid movement. They expanded north and south, spawning an important empire that stretched from the Sahara to the Iberian Peninsula in Europe.[22][23] According to a disputed Arab tradition[24][25] the Almoravids traveled south and conquered the ancient and extensive Ghana Empire around 1076.[26]

From 1644 to 1674 the indigenous peoples of the area that is modern Mauritania made what became their final effort to repel the Yemeni Maqil Arabs who were invading their territory. This effort, which was unsuccessful, is known as the Char Bouba War. The invaders were led by the Beni Hassan tribe. The descendants of the Beni Hassan warriors became the upper stratum of Moorish society. Hassaniya, a bedouin Arabic dialect named for the Beni Hassan, became the dominant language among the largely nomadic population.[27]

Colonial history

Starting in the late 19th century, France laid claim to the territories of present-day Mauritania, from the Senegal River area northwards. In 1901, Xavier Coppolani took charge of the imperial mission.[28] Through a combination of strategic alliances with Zawaya tribes and military pressure on the Hassane warrior nomads, he managed to extend French rule over the Mauritanian emirates. Beginning in 1903 and 1904, the French armies succeeded in occupying Trarza, Brakna, and Tagant, but the northern emirate of Adrar held out longer, aided by the anticolonial rebellion (or jihad) of shaykh Maa al-Aynayn and by insurgents from Tagant and the other occupied regions. In 1904, France organized the territory of Mauritania, and it became part of French West Africa, first as a protectorate and later as a colony. In 1912, the French armies defeated Adrar, and incorporated it into the territory of Mauritania.[29]

French rule brought legal prohibitions against slavery and an end to interclan warfare. During the colonial period 90% of the population remained nomadic. Gradually many individuals belonging to sedentary peoples, whose ancestors had been expelled centuries earlier, began to migrate into Mauritania. Until 1902, the capital of French West Africa was in modern-day Senegal. It was first established at Saint-Louis and later, from 1902 to 1960, in Dakar. When Senegal gained its independence that year, France chose Nouakchott as the site of the new capital of Mauritania. At the time, Nouakchott was little more than a fortified village (or ksar).[30]

After Mauritanian independence, larger numbers of indigenous sub-Saharan African peoples (Haalpulaar, Soninke, and Wolof) migrated into it, most of them settling in the area north of the Senegal River. Many of these new arrivals had been educated in the French language and customs, and became clerks, soldiers, and administrators in the new state. At the same time, the French were militarily suppressing the most intransigent Hassane tribes in the north. French pressure on those tribes altered the existing balance of power, and new conflicts arose between the southern populations and the Moors.[31][clarification needed][incomprehensible]

The great Sahel droughts of the early 1970s caused massive devastation in Mauritania, exacerbating problems of poverty and conflict. The arabized dominant elites reacted to changing circumstances, and to Arab nationalist calls from abroad, by increasing pressure to arabize many aspects of Mauritanian life, such as law and the education system. This was also a reaction to the consequences of the French domination under the colonial rule. Various models for maintaining the country's cultural diversity have been suggested, but none have been successfully implemented.[citation needed]

This ethnic discord was evident during intercommunal violence that broke out in April 1989 (the "Mauritania–Senegal Border War"), but has since subsided. Mauritania expelled some 70,000 sub-Saharan African Mauritanians in the late 1980s.[32] Ethnic tensions and the sensitive issue of slavery – past and, in some areas, present – are still powerful themes in the country's political debate. A significant number from all groups seek a more diverse, pluralistic society.[citation needed]

Conflict with Western Sahara

The International Court of Justice concluded that in spite of some evidence of both Morocco's and Mauritania's legal ties prior to Spanish colonization, neither set of ties was sufficient to affect the application of the UN General Assembly Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples to Western Sahara.[33]

In 1976, Mauritania, along with Morocco, annexed the territory of Western Sahara. After several military losses to the Polisario – heavily armed and supported by Algeria, the regional power and rival to Morocco – Mauritania withdrew in 1979. Its claims were taken over by Morocco. Due to economic weakness, Mauritania has been a negligible player in the territorial dispute, with its official position being that it wishes for an expedient solution that is mutually agreeable to all parties. While most of Western Sahara has been occupied by Morocco, the UN still considers the Western Sahara a territory that needs to express its wishes with respect to statehood. A referendum, originally scheduled for 1992, is still supposed to be held at some point in the future, under UN auspices, to determine whether or not the indigenous Sahrawis wish to be independent, as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, or to be part of Morocco.[citation needed]

Ould Daddah era (1960–1978)

In 1960, Mauritania became an independent nation.[34] In 1964 President Moktar Ould Daddah, originally installed by the French, formalized Mauritania as a one-party state with a new constitution, setting up an authoritarian presidential regime. Daddah's own Parti du Peuple Mauritanien became the ruling organization in a one-party system. The President justified this on the grounds that Mauritania was not ready for western style multiparty democracy. Under this one-party constitution, Daddah was re-elected in uncontested elections in 1976 and 1978.

Daddah was ousted in a bloodless coup on 10 July 1978. He had brought the country to near-collapse through the disastrous war to annex the southern part of Western Sahara, framed as an attempt to create a "Greater Mauritania".

CMRN and CMSN military governments (1978–1984)

Col. Mustafa Ould Salek's Military Committee for National Recovery junta proved incapable of either establishing a strong base of power or extracting the country from its destabilizing conflict with the Sahrawi resistance movement, the Polisario Front. It quickly fell, to be replaced by another military government, the Military Committee for National Salvation.

The energetic Colonel Mohamed Khouna Ould Haidallah soon emerged as its strongman. By giving up all claims to Western Sahara, he found peace with the Polisario and improved relations with its main backer, Algeria, but relations with Morocco, the other party to the conflict, and its European ally France, deteriorated. Instability continued, and Haidallah's ambitious reform attempts foundered. His regime was plagued by attempted coups and intrigue within the military establishment. It became increasingly contested due to his harsh and uncompromising measures against opponents; many dissidents were jailed, and some executed.

Slavery in Mauritania still exists, despite being officially abolished three timesː 1905, 1981, and again in August 2007. Anti-slavery activists are persecuted, imprisoned and tortured.[35][36][37]

Ould Taya's rule (1984–2005)

In December 1984 Haidallah was deposed by Colonel Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya, who, while retaining tight military control, relaxed the political climate. Ould Taya moderated Mauritania's previous pro-Algerian stance, and re-established ties with Morocco during the late 1980s. He deepened these ties during the late 1990s and early 2000s, as part of Mauritania's drive to attract support from Western states and Western-aligned Arab states. Its position on the Western Sahara conflict has been, since the 1980s, one of strict neutrality.

The Mauritania–Senegal Border War started as a result of a conflict in Diawara between Moorish Mauritanian herders and Senegalese farmers over grazing rights.[38] On 9 April 1989, Mauritanian guards killed two Senegalese.[39]

Following the incident, several riots erupted in Bakel, Dakar and other towns in Senegal, directed against the mainly Arabized Mauritanians who dominated the local retail business. The rioting, adding to already existing tensions, led to a campaign of terror against black Mauritanians,[40] who are often seen as 'Senegalese' by the Bidān (White Moors), regardless of their nationality. As low scale conflict with Senegal continued into 1990/91, the Mauritanian government engaged in or encouraged acts of violence and seizures of property directed against the Halpularen ethnic group. The tension culminated in an international airlift agreed to by Senegal and Mauritania under international pressure to prevent further violence. The Mauritanian Government expelled thousands of black Mauritanians. Most of these so-called 'Senegalese' had few or no ties with Senegal, and many have been repatriated from Senegal and Mali after 2007.[41] The exact number of expulsions is not known but the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that, as of June 1991, 52,995 Mauritanian refugees were living in Senegal and at least 13,000 in Mali.[42]: 27

Opposition parties were legalized, and a new Constitution approved in 1991 which put an end to formal military rule. But President Ould Taya's election wins were dismissed as fraudulent by some opposition groups.

In the late 1980s Ould Taya had established close co-operation with Iraq, and pursued a strongly Arab nationalist line. Mauritania grew increasingly isolated internationally, and tensions with Western countries grew dramatically after it took a pro-Iraqi position during the 1991 Gulf War.

During the mid-to late 1990s, Mauritania shifted its foreign policy to one of increased co-operation with the US and Europe. It was rewarded with diplomatic normalization and aid projects. On 28 October 1999, Mauritania joined Egypt, Palestine, and Jordan as the only members of the Arab League to officially recognize Israel. Ould Taya also started co-operating with the United States in anti-terrorism activities, a policy that was criticized by some human rights organizations.[43][44] (See also Foreign relations of Mauritania.)

During the regime of President Ould Taya Mauritania developed economically, oil was discovered in 2001 by the Woodside Company.[45]

August 2005 military coup

On 3 August 2005 a military coup led by Colonel Ely Ould Mohamed Vall ended President Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya's twenty-one years of rule. Taking advantage of Ould Taya's attendance at the funeral of Saudi King Fahd, the military, including members of the presidential guard (BASEP), seized control of key points in the capital Nouakchott. The coup proceeded without loss of life. Calling themselves the Military Council for Justice and Democracy, the officers released the following statement:

The national armed forces and security forces have unanimously decided to put a definitive end to the oppressive activities of the defunct authority, which our people have suffered from during the past years.[46]

The Military Council later issued another statement naming Colonel Ould Mohamed Vall as president and director of the national police force, the Sûreté Nationale. Vall, once regarded as a firm ally of the now-ousted president, had aided Ould Taya in the coup that had originally brought him to power, and had later served as his Security Chief. Sixteen other officers were listed as members of the council.

Though cautiously watched by the international community, the coup came to be generally accepted, with the military junta organizing elections within a promised two-year timeline. In a referendum on 26 June 2006, 97% of Mauritanians approved a new constitution that limited the duration of a president's stay in office. The leader of the junta, Col. Vall, promised to abide by the referendum and relinquish power peacefully. Mauritania's establishment of relations with Israel – it was one of only three Arab states to recognize Israel – was maintained by the new regime, despite widespread criticism from the opposition. They considered that position as a legacy of the Taya regime's attempts to curry favor with the West.

Parliamentary and municipal elections in Mauritania took place on 19 November and 3 December 2006.

2007 presidential elections

Mauritania's first fully democratic presidential elections took place on 11 March 2007. The elections effected the final transfer from military to civilian rule following the military coup in 2005. This was the first time since Mauritania gained independence in 1960 that it elected a president in a multi-candidate election.[47]

The elections were won in a second round of voting by Sidi Ould Cheikh Abdallahi, with Ahmed Ould Daddah a close second.

2008 military coup

On 6 August 2008 the head of the presidential guards took over the president's palace in Nouakchott, a day after 48 lawmakers from the ruling party resigned in protest of President Abdallahi's policies. The Army surrounded key government facilities, including the state television building, after the president fired senior officers, one of them the head of the presidential guards.[48] The President, Prime Minister Yahya Ould Ahmed Waghef, and Mohamed Ould R'zeizim, Minister of Internal Affairs, were arrested.

The coup was coordinated by General Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, former chief of staff of the Mauritanian Army and head of the presidential guard, who had recently been fired. Mauritania's presidential spokesman, Abdoulaye Mamadouba, said the President, Prime Minister, and Interior Minister had been arrested by renegade senior Mauritanian army officers and were being held under house arrest at the presidential palace in the capital.[49][50][51]

In the apparently successful and bloodless coup, Abdallahi's daughter, Amal Mint Cheikh Abdallahi, said: "The security agents of the BASEP (Presidential Security Battalion) came to our home and took away my father."[52] The coup plotters, all dismissed in a presidential decree shortly beforehand, included Ould Abdel Aziz, General Muhammad Ould Al-Ghazwani, General Philippe Swikri, and Brigadier General (Aqid) Ahmed Ould Bakri.[53]

2008-2018

A Mauritanian lawmaker, Mohammed Al Mukhtar, claimed that many of the country's people supported the takeover of a government that had become "an authoritarian regime" under a president who had "marginalized the majority in parliament".[54] However, Abdel Aziz's regime was isolated internationally, and became subject to diplomatic sanctions and the cancellation of some aid projects. Domestically, a group of parties coalesced around Abdallahi to continue protesting the coup, which caused the junta to ban demonstrations and crack down on opposition activists. International and internal pressure eventually forced the release of Abdallahi, who was instead placed under house arrest in his home village. The new government broke off relations with Israel.[55]

After the coup Abdel Aziz insisted on holding new presidential elections to replace Abdallahi, but was forced to reschedule them due to internal and international opposition. During the spring of 2009, the junta negotiated an understanding with some opposition figures and international parties. As a result, Abdallahi formally resigned under protest, as it became clear that some opposition forces had defected from him and most international players, notably including France and Algeria, now aligned with Abdel Aziz. The United States continued to criticize the coup, but did not actively oppose the elections.

Abdallahi's resignation allowed the election of Abdel Aziz as civilian president, on 18 July, by a 52% majority.

Many of Abdallahi's former supporters criticized this as a political ploy and refused to recognize the results. Despite complaints, the elections were almost unanimously accepted by Western, Arab and African countries, which lifted sanctions and resumed relations with Mauritania. By late summer, Abdel Aziz appeared to have secured his position and to have gained widespread international and internal support. Some figures, such as Senate chairman Messaoud Ould Boulkheir, continued to refuse the new order and call for Abdel Aziz's resignation.

In February 2011 the waves of the Arab Spring spread to Mauritania, where thousands of people took to the streets of the capital.[56]

In November 2014 Mauritania was invited as a non-member guest nation to the G20 summit in Brisbane.[57]

The national flag of Mauritania was changed on 5 August 2017. Two red stripes were added as a symbol of the country's sacrifice and defense.[58] In late 2018, Mauritania bribed members of the EU parlament (Antonio Panzeri) to "not speak ill of Mauritania" in what became known as the Qatar corruption scandal at the European Parliament.[59]

2019-present

In August 2019 Mohamed Ould Ghazouani was sworn in as president[60] after the 2019 elections, which were considered Mauritania's first peaceful transition of power since independence.[9]

In June 2021 former president Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz was arrested amidst a corruption probe into allegations of embezzlement.[61] In December 2023, Aziz was sentenced to 5 years in prison for corruption.[62]

In January and February 2024 there was a sudden increase of refugees from 2000 to 12,000 arriving on the Canary Islands by boat, so in March 2024, Ursula von der Leyen and Pedro Sánchez visited and the EU made a €210mn deal with Mauritania to reduce passage of African migrants through its territory towards the Canary Islands, i.e. Europe. The UN estimated that 150,000 people from Mali had fled to Mauritania.[63]

In June 2024, President Ghazouani was re-elected for a second term.[64]

Geography

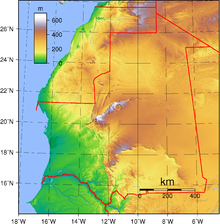

Mauritania lies in the western region of the continent of Africa, and is generally flat, its 1,030,700 square kilometers forming vast, arid plains broken by occasional ridges and clifflike outcroppings.[65] It borders the North Atlantic Ocean, between Senegal and Western Sahara, Mali and Algeria.[65] It is considered part of both the Sahel and the Maghreb. Approximately three-quarters of Mauritania is desert or semidesert.[66] As a result of extended, severe drought, the desert has been expanding since the mid-1960s.

A series of scarps face southwest, longitudinally bisecting these plains in the center of the country. The scarps also separate a series of sandstone plateaus, the highest of which is the Adrar Plateau, reaching an elevation of 500 metres or 1,600 feet.[67] Spring-fed oases lie at the foot of some of the scarps. Isolated peaks, often rich in minerals, rise above the plateaus; the smaller peaks are called guelbs and the larger ones kedias. The concentric Guelb er Richat is a prominent feature of the north-central region. Kediet ej Jill, near the city of Zouîrât, has an elevation of 915 metres (3,000 ft) and is the highest peak. The plateaus gradually descend toward the northeast to the barren El Djouf, or "Empty Quarter," a vast region of large sand dunes that merges into the Sahara Desert. To the west, between the ocean and the plateaus, are alternating areas of clayey plains (regs) and sand dunes (ergs), some of which shift from place to place, gradually moved by high winds. The dunes generally increase in size and mobility toward the north.

Belts of natural vegetation, corresponding to the rainfall pattern, extend from east to west and range from traces of tropical forest along the Sénégal River to brush and savanna in the southeast. Only sandy desert is found in the center and north of the country. Mauritania is home to seven terrestrial ecoregions: Sahelian Acacia savanna, West Sudanian savanna, Saharan halophytics, Atlantic coastal desert, North Saharan steppe and woodlands, South Saharan steppe and woodlands, and West Saharan montane xeric woodlands.[68]

The Richat Structure, dubbed the "Eye of the Sahara",[69] is a formation of rock resembling concentric circles in the Adrar Plateau, near Ouadane, west–central Mauritania.

Wildlife

Mauritania's wildlife has two main influences as the country lies in two biogeographic realms, the north sits in the Palearctic which extends south from the Sahara to roughly 19° north and the south in the Afrotropic realms. Additionally Mauritania is important for numerous birds which migrate from the Palearctic to winter there.

Most of the north to about 19° north is regarded as being in the palearctic, and is largely made up of the Sahara desert and adjacent littoral habitats. South of this is regarded as being in the Afrotropical biogeographic realm, which means that species of a predominantly Afrotropical distribution dominate the fauna. South of the Sahara is the South Saharan steppe and woodlands ecoregion which integrates into the Sahelian acacia savanna ecoregion. The southernmost part of the country lies in the West Sudanian savanna ecoregion.

Wetlands are important and the two main protected areas are the Banc d'Arguin National Park which protects rich, shallow coastal and marine ecosystems which integrates with the arid Sahara Desert and the Diawling National Park which forms the northern part of the delta of the Senegal River. Elsewhere in Mauritania wetlands are normally ephemeral and rely on the seasonal rainfall.

Government and politics

The Mauritanian Parliament is composed of a single chamber, the National Assembly. Composed of 176 members, representatives are elected for a five-year term in single-seat constituencies.

Until August 2017 the parliament had an upper house, the Senate. The Senate had 56 members, 53 members elected for a six-year term by municipal councilors with a third renewed every two years and three elected by Mauritanians abroad. It was abolished in 2017 after a referendum. President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz called for the referendum in August 2017 after the Senate rejected his proposals to change the constitution.[70]

The President of Mauritania is directly elected by absolute majority popular vote in two rounds if needed for a five-year term (eligible for a second term). The last presidential election was held on June 29, 2024, with President Mohamed Ould Ghazouani winning re-election.[71] The Prime minister is appointed by the President.[72]

Military

The Armed Forces of Mauritania (Arabic: الجيش الوطني الموريتاني, French: Armée Nationale Mauritanienne) is the defense force of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, having an army, navy, air force, gendarmerie, and presidential guard. Other services include the National Guard and national police, though they both are subordinated to the Ministry of the Interior. As of 2018, the Mauritanian armed forces budget constituted 3.9% of the country's GDP.

Hanena Ould Sidi is the current Defense Minister, and General Mokhtar Ould Bolla Chaabane is the current Chief of National Army Staff. Despite the small size it has participated in numerous conflicts in the past including Western Sahara War and Mauritania–Senegal Border War and is currently involved in Operation Enduring Freedom - Trans Sahara.

Mauritania was ranked 95th of 163 most peaceful country in the world, according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.[73]

Administrative divisions

The government bureaucracy is composed of traditional ministries, special agencies, and parastatal companies. The Ministry of Interior spearheads a system of regional governors and prefects modeled on the French system of local administration. Under this system, Mauritania is divided into 15 regions (wilaya or régions).

Control is tightly concentrated in the executive branch of the central government, but a series of national and municipal elections since 1992 have produced limited decentralization. These regions are subdivided into 44 departments (moughataa).[74]

The regions and capital district and their capitals are:

| Region | Capital | # |

|---|---|---|

| Adrar | Atar | 1 |

| Assaba | Kiffa | 2 |

| Brakna | Aleg | 3 |

| Dakhlet Nouadhibou | Nouadhibou | 4 |

| Gorgol | Kaédi | 5 |

| Guidimaka | Sélibaby | 6 |

| Hodh Ech Chargui | Néma | 7 |

| Hodh El Gharbi | Ayoun el Atrous | 8 |

| Inchiri | Akjoujt | 9 |

| Nouakchott-Nord | Dar-Naim | 10 |

| Nouakchott-Ouest | Tevragh-Zeina | 10 |

| Nouakchott-Sud | Arafat | 10 |

| Tagant | Tidjikdja | 11 |

| Tiris Zemmour | Zouérat | 12 |

| Trarza | Rosso | 13 |

Economy

Despite being rich in natural resources, Mauritania has a low GDP.[75] A majority of the population still depends on agriculture and livestock for a livelihood, even though most of the nomads and many subsistence farmers were forced into the cities by recurrent droughts in the 1970s and 1980s.[75] Mauritania has extensive deposits of iron ore, which account for almost 50% of total exports. Gold and copper mining companies are opening mines in the interior such as Firawa mine. The country's gold production in 2015 is 9 metric tons.[76]

The country's first deepwater port opened near Nouakchott in 1986.

In recent years drought and economic mismanagement have resulted in a buildup of foreign debt. In March 1999, the government signed an agreement with a joint World Bank-International Monetary Fund mission on a $54 million enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF). Privatization remains one of the key issues. Mauritania is unlikely to meet ESAF's annual GDP growth objectives of 4–5%.

Oil was discovered in Mauritania in 2001 in the offshore Chinguetti Field. Although potentially significant for the Mauritanian economy, its overall influence is difficult to predict. Mauritania has been described as a "desperately poor desert nation, which straddles the Arab and African worlds and is Africa's newest, if small-scale, oil producer".[77] There may be additional oil reserves inland in the Taoudeni basin, although the harsh environment will make extraction expensive.[78]

Sports

Sports in Mauritania are influenced by its desert terrain and its location on the Atlantic coast. Football is the most popular sport in the country, followed by athletics and basketball. The country has several football stadiums, such as the Stade Municipal de Nouadhibou in Nouadhibou.[79] Despite being ranked as the fourth-worst team in the world in 2012, Mauritania qualified for the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations.[80] In 2023, Mauritania made headlines by defeating Sudan in the AFCON 2023 qualifiers.[81]

Mauritania has been the recipient of international support for sports infrastructure. Morocco has committed to building a sports complex in the country.[82]

Demographics

| Population[83][84] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 0.7 | ||

| 2000 | 2.7 | ||

| 2021 | 4.6 | ||

As of 2021, Mauritania had a population of about 4.3 million, roughly a third concentrated in the capital and largest city, Nouakchott, on the Atlantic coast. The local population is composed of three main ethnicities: Bidhan or white Moors, Haratin or black moors, and West Africans. 30% Bidhan, 40% Haratin, and 30% others (mostly Black Sub-Saharans). Local statistics bureau estimations indicate that the Bidhan represent around 30% of citizens. They speak Hassaniya Arabic and are primarily of Arab-Berber origin. The Haratin constitute roughly 35% of the population, with many estimates putting them at around 40%. They are descendants of the original inhabitants of the Tassili n'Ajjer and Acacus Mountain sites during the Epipalaeolithic era.[85][86] The remaining 30% of the population largely consists of various ethnic groups of West African descent. Among these are the Niger-Congo-speaking Halpulaar (Fulbe), Soninke, Bambara and Wolof.[1]

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns in Mauritania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Nouakchott  Nouadhibou |

1 | Nouakchott | Nouakchott | 1,446,761 | 11 | Adel Bagrou | Hodh Ech Chargui | 37,048 |  Kiffa |

| 2 | Nouadhibou | Dakhlet Nouadhibou | 173,525 | 12 | Aïoun el Atrous | Hodh El Gharbi | 36,517 | ||

| 3 | Kiffa | Assaba | 84,101 | 13 | Hamed | Assaba | 36,448 | ||

| 4 | Vassala | Hodh Ech Chargui | 79,508 | 14 | Tintane | Hodh El Gharbi | 35,995 | ||

| 5 | Kaédi | Gorgol | 62,790 | 15 | Atar | Adrar | 35,171 | ||

| 6 | Zouérat | Tiris Zemmour | 62,380 | 16 | Néma | Hodh Ech Chargui | 35,042 | ||

| 7 | Rosso | Trarza | 61,156 | 17 | Gouraye | Guidimagha | 35,021 | ||

| 8 | Boghé | Brakna | 50,205 | 18 | Timbédra | Hodh Ech Chargui | 34,244 | ||

| 9 | Sélibaby | Guidimagha | 44,966 | 19 | Voum Legleita | Gorgol | 33,314 | ||

| 10 | Guerou | Assaba | 40,315 | 20 | Boutilimit | Trarza | 32,347 | ||

Religion

Mauritania is almost 100% Muslim, with most inhabitants adhering to the Sunni denomination.[1] The Sufi orders, the Tijaniyah and the Qadiriyyah, have great influence not only in the country, but in Morocco, Algeria, Senegal and other neighboring countries as well. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Nouakchott, founded in 1965, serves the 4,500 Catholics in Mauritania (mostly foreign residents from West Africa and Europe). In 2020, the number of Christians in Mauritania was estimated at 10,000.[87]

There are extreme restrictions on freedom of religion and belief in Mauritania; it is one of 13 countries in the world that punish atheism by death.[88]

On 27 April 2018 the National Assembly passed a law that makes the death penalty mandatory for anyone convicted of "blasphemous speech" and acts deemed "sacrilegious". The new law eliminates the possibility under article 306 of substituting prison terms for the death penalty for certain apostasy-related crimes if the offender promptly repents. The law also provides for a sentence of up to two years in prison and a fine of up to 600,000 Ouguiyas (about €14,600) for "offending public indecency and Islamic values" and for "breaching Allah's prohibitions" or assisting in their breach.[89]

Languages

Arabic is the official and national language of Mauritania. The local spoken variety, known as Hassaniya, contains many Berber words and significantly differs from the Modern Standard Arabic that is used for official communication. Pulaar, Soninke, and Wolof also serve as national languages.[1] Despite having no official status, French is used as an administrative language and as a medium of instruction in schools.[90][91] It is also widely used in the media, business, and among educated classes.[92]

Health

As of 2011, life expectancy at birth was 61.14 years.[1] Per capita expenditure on health was US$43 (PPP) in 2004.[93] Public expenditure was 2% of the GDP in 2004 and private 0.9% of the GDP in 2004.[93] In the early 21st century, there were 11 physicians per 100,000 people.[93] Infant mortality is 60.42 deaths/1,000 live births (2011 estimate).[93]

The obesity rate among Mauritanian women is high, perhaps in part due to the traditional standards of beauty in some regions by which obese women are considered beautiful while thin women are considered sickly.[94]

Education

Since 1999, all teaching in the first year of primary school is in Modern Standard Arabic; French is introduced in the second year, and is used to teach all scientific courses.[95] The use of English is increasing.[96]

Mauritania has the University of Nouakchott and other institutions of higher education, but the majority of highly educated Mauritanians have studied outside the country. Public expenditure on education was at 10.1% of 2000–2007 government expenditure.[93] Mauritania was ranked 126th out of 139 in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[97]

Human rights

The Abdallahi government was widely perceived as corrupt and restricted access to government information. Sexism, racism, female genital mutilation, child labor, human trafficking, and the political marginalization of largely southern-based ethnic groups continued to be problems.[98]

Homosexuality is illegal and is a capital offence in Mauritania.[99]

Following the 2008 coup the military government of Mauritania faced severe international sanctions and internal unrest. Amnesty International accused it of practicing coordinated torture against criminal and political detainees.[100] Amnesty has accused the Mauritanian legal system, both before and after the 2008 coup, of functioning with complete disregard for legal procedure, fair trial, or humane imprisonment. The organization has said that the Mauritanian government has practiced institutionalized and continuous use of torture throughout its post-independence history, under all its leaders.[101][102][103]

Amnesty International in 2008 alleged that torture was common in Mauritania, stating that its usage is "deeply anchored in the culture of the security forces", which use it "as a system of investigation and repression". Forms of torture employed include cigarette burns, electric shocks and sexual violence, stated Amnesty International.[104][105] In 2014, the United States Department of State identified torture by Mauritanian law enforcement as one of the "central human rights problems" in the country.[106] Juan E. Méndez, an independent expert on human rights from the United Nations, reported in 2016 that legal protections against torture were present but not applied in Mauritania, pointing to an "almost total absence of investigations into allegations of torture".[107][108]

According to the US State Department 2010 Human Rights Report,[109] abuses in Mauritania include:

mistreatment of detainees and prisoners; security force impunity; lengthy pretrial detention; harsh prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detentions; limits on freedom of the press and assembly; corruption; discrimination against women; female genital mutilation (FGM); child marriage; political marginalization of southern-based ethnic groups; racial and ethnic discrimination; slavery and slavery-related practices; and child labor.

Initiaves such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) aim to address these human rights violations in line with the Sustainable Development Goals. Through the improvements to the blue economy and green energy transition, the UNDP strives to create employment opportunities, particularly for youth and women, who are underrepresented in the Mauritanian job market.[110]

Modern slavery

Slavery persists in Mauritania, despite it being outlawed.[35] It is the result of a historical caste system, resulting in descent-based slavery.[35][111] It is estimated that those enslaved are generally darker-skinned Haratin, with their owners often being lighter-skinned Moors.[111] Although slavery also exists among the Sub-Saharan Mauritanians part of the population, with some Sub-Saharan Mauritanians owning slaves of the same skin color than them, and some estimates even stating that slavery is currently more widespread in that part of the population, in the south of the country.[112]

In 1905, the French colonial administration declared an end of slavery in Mauritania, with very little success.[113] Mauritania ratified in 1961 the Forced Labour Convention, having already enshrined abolition of slavery, albeit implicitly, in its 1959 constitution,[112] and although nominally abolished in 1981 by presidential decree, a criminal law against the ownership of slaves was enacted only in 2007.

The US State Department 2010 Human Rights Report states, "Government efforts were not sufficient to enforce the antislavery law. No cases have been successfully prosecuted under the antislavery law despite the fact that de facto slavery exists in Mauritania."[109]

In 2012 it was estimated by a CNN documentary that 10% to 20% of the population of Mauritania (between 340,000 and 680,000 people) live in slavery.[114] That estimation is however considered by several academics to be grossly overstated.[112] Modern-day slavery still exists in different forms in Mauritania.[115] According to some estimates, thousands of Mauritanians are still enslaved.[116][117][118] A 2012 CNN report, "Slavery's Last Stronghold", documents the ongoing slave-owning cultures.[119] This social discrimination is applied chiefly against the "black Moors" (Haratin) in the northern part of the country, where tribal elites among "white Moors" (Bidh'an, Hassaniya-speaking Arabs and Arabized Berbers) hold sway.[120] Slavery practices exist also within the sub-Saharan African ethnic groups of the south.

In 2012, a government minister stated that slavery "no longer exists" in Mauritania.[121] However, according to the Walk Free Foundation's Global Slavery Index, there were an estimated 90,000 enslaved people in Mauritania in 2018, or around 2% of the population.[122]

Obstacles to ending slavery in Mauritania include:

- The difficulty of enforcing any laws in the country's vast desert.[114]

- Poverty that limits opportunities for slaves to support themselves if freed.[114]

- Belief that slavery is part of the natural order of this society.[114]

Culture

Tuareg and Mauritanian silversmiths have developed traditions of traditional Berber jewellery and metalwork that have been worn by Mauritanian women and men. According to studies of Tuareg and Mauritanian jewellery, the latter are usually more embellished and may carry typical pyramidal elements.[123]

Filming for several documentaries, films, and television shows have taken place in Mauritania, including Fort Saganne (1984), The Fifth Element (1997), Winged Migration (2001), Timbuktu (2014), and The Grand Tour (2024).

The TV show Atlas of Cursed Places (2020) that aired on the Discovery Channel & National Geographic Channel had an episode that mentions Mauritania as a possible location for the lost city of Atlantis. The location they consider is a geological formation consisting of a series of rings known as the Richat Structure, which is located in the Western Sahara.

The T'heydinn is part of Moorish oral tradition.[124]

The libraries of Chinguetti contain thousands of medieval manuscripts.[125][126][127]

See also

- Index of Mauritania-related articles

- Outline of Mauritania

- The Mauritanian—2021 legal drama film

- Telephone numbers in Mauritania

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f "The World Factbook – Africa – Mauritania". CIA. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ "1: Répartition spatiale de la population" (PDF). Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat (RGPH) 2013 (Report) (in French). National Statistical Office of Mauritania. July 2015. p. v. Retrieved 20 December 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mauritania". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Mauritania)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24". United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ Diagana, Kissima (23 June 2019). "Ruling party candidate declared winner of Mauritania election". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b "First peaceful transfer of power in Mauritania's presidential polls". RFI. 22 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Global Slavery Index country data – Mauritania". Global Slavery Index. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Activists warn over slavery as Mauritania joins U.N. human rights council". reuters.com. 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Mauritania". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Mauritania – The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Shillington 2005, p. 948.

- ^ Toyin Falola, Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa [3 volumes] An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society [3 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 1037. ISBN 979-82-1604273-0.

- ^ Goerg, Odile; Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (1 July 2010). L'Afrique occidentale au temps des Français: Colonisateurs et colonisés (c. 1860–1960) (in French). La Découverte. ISBN 978-2-7071-5555-9. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Lugan, Bernard (2 June 2016). Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord: Des origines à nos jours (in French). Editions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-08535-7. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Stokes, James, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. p. 450. ISBN 9781438126760. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Suarez, David (2016). The Western Sahara and the Search for the Roots of Sahrawi National Identity (Thesis). Florida International University. doi:10.25148/etd.fidc001212.

- ^ Chaabani, H.; Sanchez-Mazas, A.; Sallami SF (2000). "Genetic differentiation of Yemeni people according to rhesus and Gm polymorphisms". Annales de Génétique. 43 (3–4): 155–62. doi:10.1016/S0003-3995(00)01023-6. PMID 11164198.

- ^ a b Sabatier, Diane Himpan; Himpan, Brigitte (28 June 2019). Nomads of Mauritania – Diane Himpan Sabatier, Brigitte Himpan – Google Books. Vernon Press. ISBN 9781622735822. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Messier, Ronald A. (2010). The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad. Praeger. pp. xii–xvi. ISBN 978-0-313-38590-2.

- ^ Norris, H.T. & Chalmeta, P. (1993). "al-Murābiṭūn". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 583–591. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- ^ Masonen, Pekka; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1996). "Not quite Venus from the waves: The Almoravid conquest of Ghana in the modern historiography of Western Africa" (PDF). History in Africa. 23: 197–232. doi:10.2307/3171941. JSTOR 3171941. S2CID 162477947. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Insoll, T (2003). The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 230.

- ^ Velton, Ross (2009). Mali: The Bradt Safari Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84162-218-7. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Mauritania – History". Country Studies. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016.

- ^ Keenan, Jeremy, ed. (18 October 2013). The Sahara. doi:10.4324/9781315869544. ISBN 9781315869544.

- ^ "Mauritania: History". www.infoplease.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Pazzanita, Anthony G. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6265-4. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020. page 369.

- ^ "Mauritanian MPs pass slavery law" Archived 9 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News. 9 August 2007.

- ^ MAURITANIA: Fair elections haunted by racial imbalance Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, IRIN News. 5 March 2007.

- ^ "Cour internationale de Justice – International Court of Justice". www.icj-cij.org. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Meredith, Martin (2005), The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence, New York: Public Affairs Publishing, p. 69, ISBN 978-1610390712

- ^ a b c "The unspeakable truth about slavery in Mauritania". The Guardian. 8 June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Mauritania: Growing repression of human rights defenders who denounce discrimination and slavery". Amnesty International. 21 March 2018.

- ^ Akinyemi, Aaron; Kupemba, Danai Nesta (29 June 2024). "Mauritania election: Jihadist, migration, slavery the key issues". BBC.

- ^ "Inventory of Conflict and Environment (ICE), Template". American University. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Diallo, Garba (1993). "Mauritania, a new Apartheid?" (PDF). bankie.info. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2011.

- ^ Duteil, Mireille (1989). "Chronique mauritanienne". Annuaire de l'Afrique du Nord (in French). Vol. XXVIII (du CNRS ed.).

- ^ Sy, Mahamadou (2000). L'Harmattan (ed.). "L'enfer de Inal". Mauritanie, l'horreur des camps. Paris. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ "Mauritania's campaign of terror, State-Sponsored Repression of Black Africans" (PDF). Human Rights Watch/Africa (formerly Africa Watch). 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Crackdown courts U.S. approval". CNN. 24 November 2003. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ "Mauritania: New wave of arrests presented as crackdown on Islamic extremists". IRIN Africa. 12 May 2005. Archived from the original on 29 November 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ "Woodside to pump Mauritania oil". 31 May 2004. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Mauritania officers 'seize power'". BBC News. 4 August 2005. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ "Mauritania vote 'free and fair'". BBC News. 12 March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ "48 lawmakers resign from ruling party in Mauritania". Tehran Times. 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- ^ "Coup in Mauritania as president, PM arrested". AFP. 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "Troops stage 'coup' in Mauritania". BBC News. 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "Coup under way in Mauritania: president's office". Archived from the original on 12 August 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.. ap.google.com

- ^ McElroy, Damien (6 August 2008). "Mauritania president under house arrest as army stages coup". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Vinsinfo. "themedialine.org, Generals Seize Power in Mauritanian Coup". Themedialine.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Mohamed, Ahmed. "Renegade army officers stage coup in Mauritania". Archived from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.. ap.google.com (6 August 2008)

- ^ "Mauritania Affirms Break with Israel". Voice of America News. 21 March 2010. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Adams, Richard (25 February 2011). "Libya's turmoil". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "G20 summit: World leaders gather in Brisbane". BBC News. 14 November 2014. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Quito, Anne (8 August 2017). "Mauritania has a new flag". Quartz. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Gian Volpicelli and Eddy Wax (11 August 2023). "What happened to Qatargate's forgotten country, Mauritania?". Politico. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Ghazouani sworn in as new Mauritanian president". www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Mauritania arrests former president amid corruption probe". Reuters. 23 June 2021. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Mauritania ex-president Aziz sentenced to 5 years for corruption". France 24. 4 December 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Laura Dubois. "Brussels to pay Mauritania for stopping Europe-bound migrants". FT. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ "Mauritania re-elects President Ghazouani for a second term". Al Jazeera.

- ^ a b Thomas Schlüter (2008). Geological Atlas of Africa: With Notes on Stratigraphy, Tectonics, Economic Geology, Geohazards, Geosites and Geoscientific Education of Each Country. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 166. ISBN 978-3-540-76373-4. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Njoki N. Wane (2009). A Glance at Africa. AuthorHouse. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-4389-7489-7. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ R. H. Hughes (1992). A Directory of African Wetlands. IUCN. p. 401. ISBN 978-2-88032-949-5. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ "The Eye Of The Sahara - Mauritania's Richat Structure". WorldAtlas. 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Mauritania Senate abolished in referendum". BBC News. 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Mauritania's President Ghazouani wins re-election, provisional results show". Reuters. 30 June 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency (2021). "Mauritania". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "2024 Global Peace Index" (PDF).

- ^ "MAURITANIA: Administrative Division Departments and Communes". Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ a b International Monetary Fund. Middle East and Central Asia Dept. (2015). Islamic Republic of Mauritania: Selected Issues Paper. International Monetary Fund. pp. 19–22. ISBN 978-1-4843-3657-1. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Gold production". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 29 November 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Mauritania junta promises free elections Archived 28 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. thestar.com (7 August 2008).

- ^ "Taoudeni Basin Overview". Baraka Petroleum. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ "Stade Municipal de Nouadhibou". Stadiums World. 7 January 2023. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Mauritania, the fourth-worst team in the world, head to the Africa Cup of Nations". The Guardian. 22 June 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Mauritania Thumps Sudan in AFCON Qualifying". beIN Sports. 21 June 2023. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Morocco to Build Sports Complex in Mauritania". Morocco World News. 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 549. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9., Quote: "Haratine. Social caste in several northwestern African countries consisting of blacks, many of whom are former slaves (...)"

- ^ Gast, M. (2000). "Harṭâni". Encyclopédie berbère – Hadrumetum – Hidjaba (in French). 22.

- ^ A. Lamport, Mark (2021). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 497. ISBN 9781442271579.

Influences—Christian influences in Mauritanian society are limited to the approximately 10,000 foreign nationals living in the country

- ^ Evans, Robert (9 December 2012). "Atheists around world suffer persecution, discrimination: report". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Mehta, Hemant (17 May 2018). "Mauritania Passes Law Mandating Death Penalty for "Blasphemy"". Patheos. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Mauritania denies banning French from parliament Archived 18 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 10 Feb 2020.

- ^ La Mauritanie adopte une loi contestée sur les langues à l'école Archived 9 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine (Mauritania adopts contested law around languages at school), AfricaNews, 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Mauritania: Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Human Development Report 2009 – Mauritania". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "Mauritania struggles with love of fat women". NBC News. 16 April 2007. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Education system in Mauritania". Bibl.u-szeged.hu. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "English is All the Rage in Mauritania – Al-Fanar Media". Al-Fanar Media. 29 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2024). "Global Innovation Index 2024. Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship". www.wipo.int. Geneva. p. 18. doi:10.34667/tind.50062. ISBN 978-92-805-3681-2. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Mauritania. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2007 Archived 22 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, US State Department, 11 March 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "LGBT relationships are illegal in 74 countries, research finds". The Independent. 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ 'Prisoner torture rising' in Mauritania, SAPA/AP, 3 December 2008.

- ^ Mauritania: Prisoner Confessions Extracted Through Torture Says Amnesty International Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, IRIN: 3 December 2008

- ^ Sillah, Ebrimah. Mauritania: 'Chains Are Jewellery for Men' Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Inter Press Service, 3 December 2008.

- ^ Mauritania: Torture at the heart of the state Archived 18 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine . Amnesty International. 3 December 2008. Index Number: AFR 38/009/2008.

- ^ Magnowski, Daniel (3 December 2008). "Amnesty says torture routine in Mauritania". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Mauritania: Torture At The Heart Of The State" (PDF). Amnesty International. 3 December 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Mauritania 2014 Human Rights Report" (PDF). United States Department of State. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "UN regrets non-application of laws against torture in Mauritania". Africa News. Agence France Presse. 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Mauritania: "Safeguards against torture must be made to work" – UN rights expert urges". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ a b 2010 Human Rights Report: Mauritania Archived 4 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine. State.gov (8 April 2011). Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Draft country programme document for Mauritania (2024–2027)". 29 June 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Peyton, Nellie (27 February 2020). "Activists warn over slavery as Mauritania joins U.N. human rights council". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Slavery in Mauritania: Differentiating between facts and fiction". Middleeasteye.net. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ John D. Sutter (March 2012). "Slavery's Last Stronghold". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 December 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Slavery's last stronghold Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. CNN.com (16 March 2012). Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Yasser, Abdel Nasser Ould (2008). Sage, Jesse; Kasten, Liora (eds.). Enslaved: True Stories of Modern Day Slavery. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7493-8. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Mauritania made slavery illegal last month". South African Institute of International Affairs. 6 September 2007. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010.

- ^ "BBC World Service – The Abolition season on BBC World Service". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ "Mauritania (Tier 3)" (PDF). Report. US Dept. of State. pp. 258–59. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Slavery's last stronghold" Archived 29 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, CNN.com (16 March 2012). Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Freedom Fighter: A slaving society and an abolitionist's crusade" Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, New Yorker, 8 September 2014

- ^ "Mauritanian minister responds to accusations that slavery is rampant". CNN. 17 March 2012. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

I must tell you that in Mauritania, freedom is total: freedom of thought, equality – of all men and women of Mauritania... in all cases, especially with this government, this is in the past. There are probably former relationships – slavery relationships and familial relationships from old days and of the older generations, maybe, or descendants who wish to continue to be in relationships with descendants of their old masters, for familial reasons, or out of affinity, and maybe also for economic interests. But (slavery) is something that is totally finished. All people are free in Mauritania and this phenomenon no longer exists. And I believe that I can tell you that no one profits from this commerce.

- ^ "Country Data | Global Slavery Index Mauritania", Global Slavery Index, Walk Free Foundation, 2018, archived from the original on 20 May 2020, retrieved 6 January 2019

- ^ Liu, Robert K. (2018). "Tuareg amulets and crosses: Saharan/Sahelian innovation and aesthetics". Ornament (pdf). 40 (3): 58–63.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "UNESCO – Moorish epic T'heydinn". ich.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "Mauritanian manuscripts preserved through digital technology". www.efe.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Mandraud, Isabelle (27 July 2010). "Mauritania's hidden manuscripts". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "The Libraries of Chinguetti". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

General and cited references

- US State Department Archived 4 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Mauritania – Country Page Archived 15 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Explanatory notes

Further reading

- Foster, Noel (2010). Mauritania: The Struggle for Democracy. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1935049302.

- Hudson, Peter (1991). Travels in Mauritania. Flamingo. ISBN 978-0006543589.

- Murphy, Joseph E (1998). Mauritania in Photographs. Crossgar Press. ISBN 978-1892277046.

- "Slavery's last stronghold". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Pazzanita, Anthony G (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810855960.

- Ruf, Urs (2001). Ending Slavery: Hierarchy, Dependency and Gender in Central Mauritania. Transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3933127495.

- Sene, Sidi (2011). The Ignored Cries of Pain and Injustice from Mauritania. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1426971617.

External links

- République Islamique de Mauritanie (official government website at archive.org) (in Arabic)

- République Islamique de Mauritanie (official government website at archive.org) (in French)

- Mauritania. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Mauritania web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries