Sack of Dinant

| The Sacking of Dinant | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Rape of Belgium in World War I | |

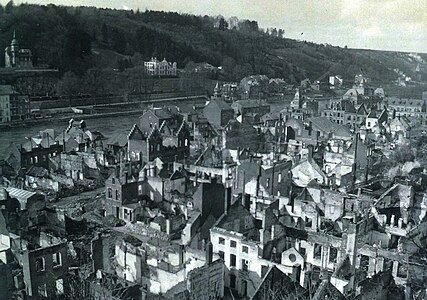

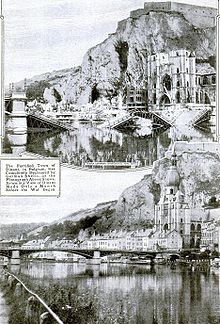

Devastated Dinant (top) and as it was a month before the war (bottom) | |

| Native name | Sac de Dinant |

| Location | Dinant, Namur Province, Wallonia, Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°15′40″N 4°54′43″E / 50.26111°N 4.91194°E |

| Date | 21–28 August 1914 |

| Target | Belgian civilians |

Attack type | War crime, massacre |

| Deaths | 674 |

| Perpetrators | |

| Motive | Presumed presence of francs-tireurs |

The Sack of Dinant[nb 1] or Dinant massacre[nb 2] refers to the mass execution of civilians, looting and sacking of Dinant, Neffe and Bouvignes-sur-Meuse in Belgium, perpetrated by German troops during the Battle of Dinant against the French in World War I. Convinced that the civilian population was hiding francs-tireurs, the German General Staff issued orders to execute the population and set fire to their houses.

On August 23, 1914, German troops carried out a brutal attack that led to the deaths of approximately 674 men, women, and children. The violence continued for several days, resulting in the destruction of about two-thirds of Dinant's buildings. Prior to this, the civilian population had been disarmed on August 6 and had been instructed not to resist the invading forces.

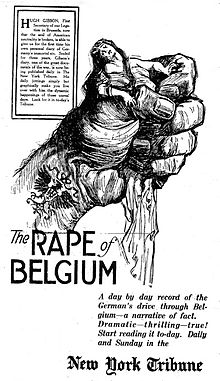

Belgium vehemently protested the massacre, and the global community was outraged, referring to the incident along with other atrocities during the German invasion as the "Rape of Belgium". Denied for many years, it was only in 2001 that the German government issued an official apology to both Belgium and the victims' descendants.

Description

The locations

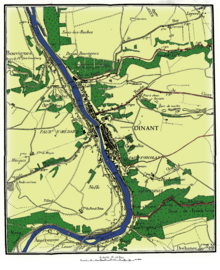

The topography of the region significantly influenced the outcome of the Dinant massacre. The town, primarily situated on the right bank of the Meuse River, is bordered by the river on one side and a rocky outcrop with a citadel, known as the "Montagne," on the other. Dinant extends approximately four kilometers from north to south. The narrower sections of the town, where the road and towpath are only a few meters wide, contrast with the broader areas, which measure up to three hundred meters. The main bridge across the Meuse connected the left-bank area of Saint-Médard with the station district on the right bank. In 1914, a pedestrian bridge linked the municipalities of Bouvignes-sur-Meuse (left bank) and Devant-Bouvignes (right bank). To the north of the town were the Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe neighborhood and Leffe faubourg. To the south, the Rivages and Saint-Nicolas neighborhoods extended from Froidvau. On the left bank, opposite the Bayard rock, was the village of Neffe. The town had limited access roads, which affected the German troops' ability to navigate and control the area during the attack.[1][2][3][4]

Historical context

Start of World War I

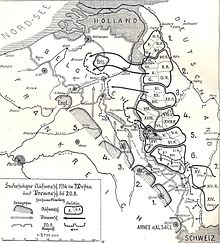

On August 4, 1914, implementing the Schlieffen plan, the German army invaded Belgium shortly after issuing an ultimatum to the Belgian government, requesting permission for German troops to pass through Belgian territory. King Albert and his government refused to compromise Belgium's neutrality and territorial integrity.[5]

In August 1914, Dinant had a population of 7,890.[6][7] On August 6, 1914, Burgomaster Arthur Defoin ordered the residents of Dinant to deposit their weapons and ammunition at the town hall. This measure was also implemented in Bouvignes-sur-Meuse.[nb 3][8][9] The mayor stated:[10]

Inhabitants are formally warned that civilians may not engage in any attacks or violence by firearms or other weapons against enemy troops. Such attacks are prohibited by the just gentium and would expose their perpetrators, and perhaps even the town, to the most serious consequences. Dinant, August 6, 1914, A. Defoin.

On the morning of August 6, 1914, a company of thirty carabinieri-cyclists[11] from the 1er régiment de chasseurs à pied arrived in Dinant. In the afternoon, the first German reconnaissance patrol made a quick incursion into town. Two uhlans advanced into rue Saint-Jacques, prompting the Garde Civique to open fire, though no hits were reported. A carabinieri-cyclist fired his rifle, wounding a German soldier and his horse in the arm. The cyclist fled on foot but was quickly apprehended, while the wounded German was treated by Dr. Remy. In the evening, the vanguard of the French 5th Army, the 148th régiment d'infanterie, took up positions to defend the bridges at Bouvignes-sur-Meuse and Dinant. On August 7, the carabinieri-cyclists were recalled to Namur. Over the following days, skirmishes occurred between the French and German forces, with a hussar being killed on August 11. The Germans subsequently ceased their scouting missions and employed their air force to assess the troop deployments.[12]

German defeat of August 15, 1914

Two cavalry divisions, commanded by Lieutenant-General von Richtoffen, formed the vanguard of the 3rd German Army. These divisions consisted of the Guards Cavalry Division and the 5th Division, supported by 4-5 battalions of chasseurs à pied, along with two groups of artillery and machine guns. The infantry component, numbering over 5,000 men, was tasked with crossing the Meuse River between Houx (Belgium), Dinant, and Anseremme.[7]

At 6 a.m. on August 15, the Germans commenced bombing both banks of the Meuse. The bombardment first targeted the civil hospital, despite its prominent red cross. The Château de Bouvignes, repurposed as a field hospital for wounded French soldiers, was similarly destroyed.[13] The fighting intensified as the German forces captured the citadel overlooking the town and attempted to cross the Meuse. They were close to succeeding when the French Deligny division, newly authorized to intervene, used its 75 mm guns to silence the German artillery and help repel the assault.[14]

The Germans eventually withdrew from Dinant, leaving behind approximately three thousand dead, wounded, prisoners, or missing. When the people of Dinant saw the French flag replacing the German colors atop the citadel, they sang "La Marseillaise".[15] In the citadel, the French discovered that wounded French soldiers had been brutally killed; one corporal of the 148th was found hanging by his belt from a shrub, with his genitals mutilated. Over the following week, enemy troops reorganized. General Lanrezac and his forces advanced to Entre-Sambre-et-Meuse, while von Hausen's troops positioned themselves along the front between Namur and Givet.[16][17]

The myth of the francs-tireurs

Since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the concept of "francs-tireurs" has been a significant concern among German soldiers and their leaders. Manuals on military strategy, such as Kriegsgebrauch im Landkriege, published in 1902, even advised officers and troops to adopt severe measures against "francs-tireurs."[18] This belief heavily influenced the perception and actions of Saxon troops during August 1914. When patrols went missing or the source of gunfire was unclear, "francs-tireurs" were often blamed.[19][20][21] Officers sometimes propagated rumors, occasionally driven by a desire to incite hostility and aggression among their forces.[22][23]

Moreover, the presence of the Civic Guard during the early stages of the invasion reinforced the German perception of it as an armed civilian militia. Established during the Belgian Revolution of 1830, the Civic Guard is composed of middle-class citizens tasked with protecting the territorial integrity of Belgium. On August 6, a community ordinance disarmed the civilian population of Dinant; however, the Civic Guard, which remained mobilized until the morning of August 15, was not disarmed until August 18.[24]

The crushing defeat on August 15, which resulted in 3,000 soldiers being wounded, coupled with the playing of "La Marseillaise" after the town was liberated, exacerbated the animosity of the occupying German forces towards the local population.[25] As a consequence, "eight days later, the enemy avenged themselves cruelly on the residents of Dinant."[26]

From August 21 onwards, German troops grappled with the trauma of this perceived defiance. Alcohol, looted from homes, was heavily consumed as a means to sustain morale,[27][28] leading to increased disorder and chaos throughout the subsequent week.[29]

The city of Dinant, situated at the bottom of a steep, narrow valley, presented challenges in identifying the source of the gunfire and tracking projectiles that ricocheted off its rocky terrain.[30][31] French troops positioned on the elevated terrain of the left bank fired whenever they found an advantageous angle. The disordered fighting and smoke from fires often led to German soldiers being inadvertently shot by their comrades.[32] These conditions reinforced the German soldiers' belief that they were being targeted by enemy francs-tireurs.[33][28] This distorted perception of reality, exacerbated by the stress of battle, led to what Arie Nicolaas Jan den Hollander terms "war psychosis", driving the soldiers to engage in violent reprisals.[34][35]

The unfolding of events

The day before: "Tomorrow, Dinant all burned and killed!"

On August 21, certain German officers enunciated their intentions unambiguously. A captain informed the parish priest of Lisogne, "Tomorrow, Dinant will be burned and killed! We have lost too many men!"[36][37]

During the night of August 21 to 22, the civilian population of Dinant experienced their first skirmishes. A German reconnaissance patrol, joined by a number of unruly soldiers, raided Rue Saint-Jacques.[38] This operation involved a diverse battalion, including members of the 2nd Battalion of the No. 108 Rifle Regiment and the 1st Company of the No. 12 Pioneer Battalion. The patrol advanced[nb 4] from the elevated area on the right bank and reached as far as the Meuse. The German forces killed seven civilians and used incendiary explosives devices to destroy approximately twenty houses, resulting in the deaths of five more people.[39][40] The Germans described this as a "reconnaissance in force" operation, while Maurice Tschoffen characterized it as "the escapade of a group of drunken soldiers."[39] According to the war diary of one of the battalions involved, the raid was ordered at the brigade level with the intent to capture Dinant, expel its defenders, and cause maximum destruction.[39] After the war, Soldier Rasch recounted an incident where, upon reaching Rue Saint-Jacques one night, the soldiers, seeing a lit café, threw a hand grenade inside, leading to a fusillade.[nb 5] This act exacerbated the panic, with gunfire appearing to come from all directions, including from residential homes. Rasch’s company lost eight soldiers, and his captain was severely injured. In total, the raid resulted in the deaths of 19 German soldiers and injuries to 117 others. Contributing factors to the high German casualties included the use of torches by German troops, which made them easy targets for French soldiers, and the possibility that, in the chaos, German soldiers may have accidentally fired on their comrades. This incident further entrenched the myth of the francs-tireurs.[41]

The initial disturbances prompted many residents to flee from the right bank for safety. They were required to present passes issued by local authorities to cross to the left bank. Due to the barricading of the Dinant and Bouvignes bridges, some families escaped via tourist barges.[42] Approximately 2,500 individuals from Dinant managed to find refuge behind French lines.[43] However, by noon on August 22, the French authorities prohibited further crossings to avoid disrupting troop movements.[42] The French 5th Army’s First Corps was replaced by the 51st Reserve Infantry Division and the 273rd Infantry Regiment (France). A small group from the British Expeditionary Force was also in the area.[44] The 51st Reserve Infantry Division thus faced three German army corps across a front extending over thirty kilometers. At Dinant, the 273rd Infantry Regiment confronted the XIIth Army Corps (1st Saxon Corps) of the entire Saxon Army. Given the impracticality of a French assault, the French forces focused on obstructing the German XII Corps' crossing of the Meuse. Consequently, in the mid-afternoon,[45] the French detonated the Bouvignes-sur-Meuse bridge while preserving the Dinant bridge. They entrenched themselves on the left bank, abandoning their efforts to maintain a presence on the right bank while preparing for the approaching German forces.[16][42][46]

August 23, 1914: the Ransack of Dinant

On August 23, 1914, the XIIth Army Corps (1st Saxon Corps) entered Dinant via four separate routes.[47] To the north, the 32nd Division advanced through the sector between Houx and the Faubourg de Leffe. The 178th Regiment of the 64th Brigade moved through the Fonds de Leffe. As they progressed, German forces killed all civilians in their path. Thirteen men were shot at Pré Capelle by six men from the 103rd Saxon Regiment, and seventy-one were murdered near the "paper mill." Paul Zschocke, a non-commissioned officer in the 103rd Infantry Regiment, reported being ordered by his company commander to search for "francs-tireurs" and "shoot anyone found".[45] Houses were systematically searched, and civilians were either executed or taken to the Prémontrés Abbey. At ten o'clock in the morning, the abbey's religious, unaware of the impending danger, gathered the 43 men present at the request of the German officers. They were subsequently shot in Place de l'Abbaye.[nb 6][45] The monks were held hostage under the pretext that they had fired on German troops. Major Fränzel, who spoke French, demanded a ransom of 60,000 Belgian francs, which was later reduced to 15,000 Belgian francs after consultation with his superiors.[48][49][50]

That evening, 108 civilians[51] who had been hiding in the cellars of the large Leffe fabric factory decided to surrender. The factory director, Remy Himmer, who was also the vice-consul of the Argentine Republic, along with his relatives and some workers, was immediately arrested. Women and children were sent to the Prémontrés convent. Despite protests from Lieutenant-Colonel Blegen,[52] Remy Himmer and 30 men were executed in Place de l'Abbaye, which was still strewn with the morning’s victims. Later that evening, the Grande Manufacture was set on fire.[49] The massacre continued throughout the night in the Abbey district: houses were looted and burned, and male civilians were shot. By the time the Germans left Leffe, only a dozen men remained alive. The 32nd Division then constructed a boat bridge opposite the Pâtis de Leffe and crossed the Meuse.[16][51][53]

Regiments No. 108 and No. 182 of the 46th Brigade, along with the 12th and 48th Artillery Regiments, advanced down Rue Saint-Jacques. By 6:30 a.m., their vanguard had reached the slaughterhouse, which was soon set ablaze. Finding fewer civilians in the dwellings, the German forces set fire to the entire district. All male civilians who had remained in the area were executed without exception. In the afternoon, a platoon from the 108th Infantry Regiment[54] discovered around one hundred civilians seeking refuge in the Nicaise brewery. The women and children were sent to the Leffe Abbey, while the thirty men were taken to Rue des Tanneries. There, they were lined up along the Mur Laurent and executed. Three of the men managed to escape under the cover of dusk.[16][53][54]

During the conflict, looted furniture from nearby houses was used by members of the 182nd Infantry Regiment to construct a barricade. Despite being unarmed, a young man suspected of being a sniper was captured, bound, and used as a human shield. As their troops were firing upon them, the unit shot and killed the hostage before retreating.[54]

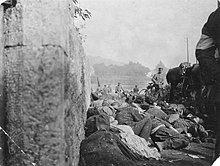

The German 100th Regiment descended from Montagne de la Croix and launched an assault on the Saint-Nicolas district. The area was systematically ravaged from eight in the morning until eight in the evening.[nb 7][55] Maurice Tschoffen, a witness to the events, described how soldiers marched in two lines alongside the houses, with those on the right monitoring the left, both with their fingers on the triggers, prepared to fire at any moment. Groups of soldiers formed in front of each doorway, stopping to fire at the houses, focusing particularly on the windows. Numerous bombs were thrown into the cellars. Two men were fatally shot on their doorstep.[56] Similar to the events on Rue Saint-Jacques, civilians were used as human shields in Place d'Armes, with some being struck by French bullets fired from across the river. Taking advantage of the chaos, the German forces crossed the square and advanced towards the Rivages area. They set houses on fire and gathered civilians at the Bouille house, later dispersing them among various buildings, including the café, forge, and stables. As the fires spread, they directed them towards the prison.[56] Eventually, men and women were separated at the base of Croix Mountain. Despite being asked to leave, the women and children stayed behind, waiting for news of their husbands, brothers, and sons. Some men were imprisoned, while 137 others were arranged in four rows along Maurice Tschoffen's garden wall. Colonel Bernhard Kielmannsegg of the 100th Infantry Regiment issued the order for execution. Following this, two rounds of gunfire and machine-gun fire were directed at the bodies from the Frankinet garden's terrace.[57][58] While approximately 30 men pretended to be dead, 109 were killed. Most of the wounded individuals escaped from the pile of corpses during the night, and five of them were later apprehended and executed.[16][53][54][59][60] Major von Loeben, who led one of the two execution teams (the other led by Lieutenant von Ehrenthal), testified to a German inquiry commission, stating, "I presume that these were the men who had engaged in hostile activities against our troops".[61]

To the south of Dinant, the German 101st Regiment arrived that afternoon via the Froidvau road and constructed a boat bridge upstream from Bayard Rock.[62] Several civilians were taken hostage, including a group from Neffe who were forced to cross the river on boats. Around 5 p.m., the Germans faced intense gunfire from the left bank despite advancing 40 meters along the Meuse.[63] Claiming that the French were firing upon them, the Germans executed 89 hostages against the wall of the Bourdon garden. This incident resulted in the deaths of 76 individuals, including 38 women and seven children, the youngest being three-week-old Madeleine Fivet. Following this, the 101st Regiment crossed the Meuse to Neffe. A group of 55 civilians had sought refuge in a small aqueduct beneath the railroad line. Under the command of Karl Adolf von Zeschau, the regiment attacked with rifles and grenades, resulting in the deaths of 23 civilians and injuries to 12 others.[16][53]

The Dinant bridge was destroyed by the French around 6 p.m. on August 23 as they retreated along the Philippeville road. German brutality continued in the following days before eventually diminishing. Civilians who emerged from hiding too soon often faced execution. In the aftermath, civilians were forced to bury the numerous bodies scattered across the pavements and plazas of Dinant and its surroundings.[16][53]

Earlier, at the prison, the Germans separated the women and children from the men. The men, aware of their impending fate, received absolution from a priest. Confusion arose when gunfire near the Tschoffen wall led some prisoners and their jailers to believe that the French were attempting to retake the town. However, the execution did not take place, and the prisoners were eventually moved to Bayard Rock. The women and children were forced to march to Dréhance and Anseremme. The 416 men, under Captain Hammerstein's command, awaited deportation to Germany.[16][53] They were directed to Marche and then transferred to Melreux (Belgium) station. The men were divided into groups of 40 and transported in cattle cars to Kassel prison in Germany.[64]

The prisoners' journey was severely hampered by the brutality inflicted by German troops and the local populations they encountered.[65] Some individuals were executed without trial after experiencing severe mental distress. The conditions of imprisonment were extremely harsh, leading to the deaths of some prisoners who had been seriously injured during the Dinant events and subsequently deported. Prison regulations prohibited family members from sharing the same cell. Furthermore, four inmates were required to share cells measuring only 9 m², with no straw mattresses provided.[66] During the first eight days, prisoners were not permitted any outdoor excursions. The schedule was later adjusted to allow one outing per week, which was eventually increased to three. Maurice Tschoffen, the King's Public Prosecutor in Belgium, reported that the prison governor informed him that the military authorities in Berlin were convinced that no shots had been fired in Dinant. The source of this assertion is unclear. Tschoffen noted that there appeared to be no justification for their arrest, though the reasons for their eventual release remained uncertain.[67] In a subsequent discussion in Belgium, General von Longchamps shared his findings on the Dinant events, stating, "From my investigation, it appears that no civilians fired at Dinant; however, there might have been some French soldiers disguised as civilians who fired. Additionally, in combat training, individuals can sometimes exceed the limits of their training."[67]

Thirty-three clergymen were apprehended at the regimental school in Dinant and were later imprisoned in Marche for one month.[64]

Dinant in ruins

During the sack, 750 buildings were burnt down or demolished, with two-thirds of the buildings destroyed.[68]

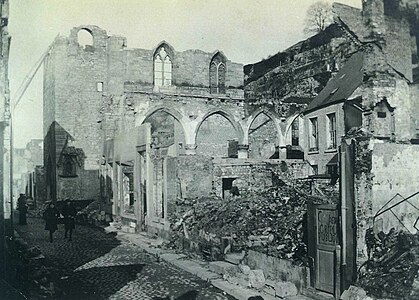

- The collegiate church and the destroyed bridge

- The City Hall

- The City Hall and Post Office from the left bank

- Rue Grande

- The Saint-Pierre district

- Saint-Pierre church

- Place Patenier

- The ruins of Belle-vue College

- Dinant was in ruins in March 1915, with only the roads cleared.

The protagonists of the event

The German command

The Third German Army was under the command of Saxon Max von Hausen and was organized into three corps. The XII Corps (1st Saxon Corps), commanded by Karl Ludwig d'Elsa, was assigned the task of capturing Dinant and crossing the Meuse at that location. The XII Corps was further subdivided into two divisions: the 32nd Infantry Division, commanded by Lieutenant-General Horst Edler von der Planitz, and the 23rd Infantry Division, led by Karl von Lindeman.[69][70]

Max von Hausen, a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, advised the civilian population to refrain from taking up arms against German troops. As a result, the directive at all levels of command was to "treat civilians with the utmost rigor."[70]

The German General Staff began receiving reports of snipers in the east as the 3rd Army assembled. The civilian population, allegedly incited by a biased press, the clergy, and the government, was purportedly acting on prearranged instructions. In response, it was deemed essential to address the situation with the utmost seriousness and implement stringent measures without delay.[71]

The belief in the "franc-tireurs myth" led the Germans to take severe actions against the civilian population. During the Battle of Dinant, certain battalions and regiments were ordered to engage in acts of intimidation against civilians. This directive was part of the broader strategy in the conflict with the French.[72]

This situation was evident with Infantry Regiment No. 178, commanded by Colonel Kurt von Reyher, who was under the overall command of Brigade Commander General Major Morgenstern-Döring. The troops were instructed to use forceful measures and act ruthlessly without regard for the perceived rebellious civilians.[73][74] Major Kock of the 2nd Battalion was directed by von Reyher to "purge the houses." Captain Wilke, who commanded the 6th and later the 9th company, led several operations aimed at intimidating the civilian population, particularly in the Fonds de Leffe and at the abbey.[70][75]

According to the 23rd Infantry Division’s reports, the executions, looting, and burning in Les Rivages, St. Nicolas district, and Neffe, south of the city, were primarily carried out by the 101st Saxon Grenadier Regiment, led by Colonel Meister, and the 100th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Kilmannsegg, under the coordination of Staff Warrant Officer Karl Adolf von Zeschau. Major Schlick, commanding the 3rd and 4th companies of Regiment No. 101, was notably active in these operations.[76][77]

After the sacking of Leffe, the 178th Infantry Regiment crossed the Meuse following the withdrawal of French troops and arrived in Bouvignes-sur-Meuse, where it committed numerous violent acts resulting in the deaths of 31 individuals.[78] The German Third Army, having been delayed for one week, continued its advance, leaving behind a country devastated by looting, arson, and civilian executions. The Germans faced both the French forces and the perceived threat of francs-tireurs.[79]

In February 1915, the first issue of the clandestine La Libre Belgique asserted: "There is something more robust than the Germans; it is the truth."[80]

The victims

During the siege of Dinant, 674 civilians lost their lives, including 92 women, 18 individuals over the age of 60, and 16 individuals under the age of 15.[nb 8] Among the 577 male victims, 76 were over the age of 60 and 22 were under the age of 15. The oldest victim was 88 years old, and 14 children were under the age of 5, with the youngest being only 3 weeks old.[81]

A list of the victims' names was quickly circulated through an obituary. The first edition, published in 1915 by Dom Norbert Nieuwland, listed 606 names.[82] The occupying military authorities required the population to provide copies of this obituary under threat of severe punishment.[83]

In 1922, Nieuwland and Schmitz recorded 674 victims, including 5 who were missing.[84] By 1928, Nieuwland and Tschoffen confirmed the same number of victims and missing persons.[85] Finally, just before the centennial, Michel Coleau and Michel Kellner revised the obituary and identified a total of 674 victims and three unidentified individuals.[86]

| See the obituary[86] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Surname | Name | Sex | Age | <15 years old | Profession | Location |

| 1 | Absil | Joseph | M | 46 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 2 | Absil | Lambert | M | 59 | stone mason | Devant-Bouvignes | |

| 3 | Adnet | Ferdinand | M | 48 | car rental | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 4 | Alardo | Isidore | M | 20 | cultivator | Bonair | |

| 5 | Alardo | Joseph | M | 18 | cultivator | Herbuchenne (Alardo farm) | |

| 6 | Alardo | Martin | M | 53 | farmer | Bonair | |

| 7 | Alardo | Martin Désiré | M | 17 | cultivator | Bonair | |

| 8 | Altenhoven | Marie | F | 14 | yes | Rue du faubourg Saint-Nicolas | |

| 9 | Anciaux | Euphrosine | F | 85 | pensioner | Place d'Armes and prison | |

| 10 | Anciaux | Robert | M | 32 | police officer | Al' Bau | |

| 11 | Andre | Marie | F | 88 | without profession | Bourdon Wall | |

| 12 | Andrianne | Victor | M | 59 | janitor | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 13 | Angot | Emile | M | 48 | threader | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 14 | Ansotte | Hector | M | 18 | student | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 15 | Ares (Aeres) | Armand | M | 33 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 16 | Ares (Aeres) | Emile | M | 66 | pig farmer | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 17 | Baclin | Jules | M | 32 | marble mason | Paper Mill | |

| 18 | Bailly | Félix | M | 41 | employee | Place d'Armes and prison | |

| 19 | Balleux | Félix | M | 16 months | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 20 | Banse | Gustave | M | 30 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 21 | Bara(s) | Auguste | M | 15 | student | Bourdon Wall | |

| 22 | Barre | Georges | M | 55 | employee | Collège communal | |

| 23 | Barthelemy | Gustave | M | 30 | factory worker | Laurent Wall | |

| 24 | Barthelemy | Jean-Baptiste | M | 23 | weaver | Laurent Wall | |

| 25 | Barzin | Léopold | M | 71 | honorary deputy court clerk | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 26 | Bastin | Herman | M | 33 | postal worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 27 | Batteux | Marie | F | 42 | servant | Rue Grande | |

| 28 | Bauduin | Edouard | M | 42 | employee | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 29 | Baujot | Alfred | M | 46 | boatman | Bourdon Wall | |

| 30 | Baujot | Maria | F | 5 | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 31 | Baujot | Marthe | F | 13 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 32 | Baussart | Dieudonnée | F | 78 | housewife | Rue des Fossés | |

| 33 | Bertulot | Ernest | M | 48 | marble mason | Pré Capelle | |

| 34 | Betemps | Auguste | M | 27 | gardener | Bourdon Wall | |

| 35 | Betemps | Maurice | M | 19 months | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 36 | Bietlot | Charles | M | 76 | without profession | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 37 | Bietlot | Jean | M | 40 | brewery worker (warehouseman) | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 38 | Biname | Alphonse | M | 37 | cement manufacturer | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 39 | Blanchard | Henri | M | 48 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 40 | Bon | Célestin | M | 74 | domestic | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 41 | Bony (Frère Herman-Joseph) | Jean-Antoine | M | 60 | religious (convers) | Leffe (aqueduct) | |

| 42 | Bouchat | Théophile | M | 68 | trader | Tienne d'Orsy | |

| 43 | Bouche | Gustave | M | 53 | cobbler | Paper Mill | |

| 44 | Bouille | Amand | M | 36 | blacksmith | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 45 | Bourdon | Alexandre | M | 74 | trader | Bourdon Wall | |

| 46 | Bourdon | Edmond | M | 62 | deputy court clerk | Bourdon Wall | |

| 47 | Bourdon | Henri | M | 17 | student | Bourdon Wall | |

| 48 | Bourdon | Jeanne -Henriette | F | 33 | seamstress | Bourdon Wall | |

| 49 | Bourdon | Jeanne-Marie | F | 13 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 50 | Bourdon | Joseph | M | 56 | cabaretier | Rue Sax | |

| 51 | Bourdon | Louis | M | 39 | cultivator | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 52 | Bourguet | Eugène | M | 30 | journalist | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 53 | Bourguignon | Clotilde | F | 68 | without profession | Bourdon Wall | |

| 54 | Bourguignon | Edmond | M | 16 months | yes | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 55 | Bourguignon | Jean-Baptiste | M | 29 | truck driver | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 56 | Bovy | Adèle | F | 29 | housewife | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 57 | Bovy | Constant | M | 23 | automobile driver | Jardins du Casino | |

| 58 | Bovy | Héloïse | F | 23 | factory worker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 59 | Bovy | Marcel | M | 4 | yes | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 60 | Bradt | Julien | M | 33 | cobbler | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 61 | Brihaye | Alfred | M | 25 | hotel garçon | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 62 | Broutoux | Emmanuel | M | 54 | employee mortgage office | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 63 | Bulens | Alfred | M | 26 | threader | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 64 | Bulens | Henri | M | 53 | threader | Paper Mill | |

| 65 | Bulens | Louis | M | 51 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 66 | Bultot | Alexis | M | 34 | cultivator | Malaise Farm | |

| 67 | Bultot | Alphonse | M | 20 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 68 | Bultot | Camille | M | 14 | yes | weaver | Neffe (aqueduct) |

| 69 | Bultot | Emile | M | 39 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 70 | Bultot | Joseph | M | 29 | cultivator | Malaise Farm | |

| 71 | Bultot | Jules | M | 31 | cultivator | Malaise Farm | |

| 72 | Bultot | Léonie | F | 39 | housewife | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 73 | Bultot | Norbert-Adelin | M | 35 | truck driver | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 74 | Bultot | Norbert-Alfred | M | 9 | yes | schooler | Neffe (aqueduct) |

| 75 | Burnay | Zoé | F | 22 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 76 | Burniaux | Ernest | M | 36 | clothes cutter | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 77 | Burton | Euphrasie | F | 75 | market gardener | Bourdon Wall | |

| 78 | Calson | Alfred | M | 61 | carpenter | Paper Mill | |

| 79 | Capelle | Joseph-Jean | M | 62 | cultivator | Pré Capelle | |

| 80 | Capelle | Joseph-Martin | M | 35 | postage factor | Paper Mill | |

| 81 | Carriaux | Charles | M | 36 | maneuver | Leffe (convent) | |

| 82 | Cartigny | Henri | M | 25 | factory worker (terrassier) | Paper Mill | |

| 83 | Cartigny | Hubert | M | 53 | marble mason | Pré Capelle | |

| 84 | Cartigny | Léon | M | 28 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 85 | Casaquy | Auguste | M | 49 | journalist | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 86 | Cassart | Alexis | M | 17 | factory worker | Laurent Wall | |

| 87 | Cassart | Camille | M | ? | factory worker | ? | |

| 88 | Cassart | François | M | 36 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 89 | Cassart | Hyacinthe | M | 43 | factory worker | Laurent Wall | |

| 90 | Chabotier | Joseph | M | 38 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 91 | Chabotier | Jules | M | 18 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 92 | Chabotier | Louis | M | 16 | factory worker | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 93 | Charlier | Anna | F | 15 | without profession | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 94 | Charlier | Auguste | M | 56 | valet parker | Rue des Basses Tanneries | |

| 95 | Charlier | Georgette | F | 9 | yes | schooler | Neffe (aqueduct) |

| 96 | Charlier | Henri | M | 40 | weaver | Leffe (convent) | |

| 97 | Charlier | Jules | M | 35 | journalist | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 98 | Charlier | Maurice | M | 16 | employee to the railway | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 99 | Charlier | Saturnin | M | 40 | store garçon | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 100 | Charlier | Théodule | M | 48 | glassmaker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 101 | Charlot | Léon | M | 25 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 102 | Cletie | Léopold | M | 32 | security guard | Bourdon Wall | |

| 103 | Colignon | Georges | M | 16 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 104 | Colignon | Joseph | M | 46 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 105 | Colignon | Lambert | M | 43 | dressmaker | Paper Mill | |

| 105 | Colignon | Louis | M | 38 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 107 | Colignon | Victor | M | 42 | weaver | Rue du faubourg Saint-Nicolas | |

| 108 | Colin | Auguste | M | 60 | mason | Rue Sax | |

| 109 | Colin | Héloïse | F | 75 | without profession | Rue Grande | |

| 110 | Collard | Emile | M | 75 | cobbler | Bourdon Wall | |

| 111 | Collard | Florent | M | 39 | ceiling operator | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 112 | Collard | Henri | M | 37 | ceiling operator | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 113 | Collard | Joseph | M | 77 | former railway worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 114 | Colle | Camille | M | 47 | trader | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 115 | Colle | Georges | M | 19 | student | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 116 | Colle | Henri | M | 22 | house painter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 117 | Colle | Léon | M | 16 | student | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 118 | Collignon | Arthur | M | 16 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 119 | Collignon | Camille | M | 30 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 120 | Collignon | Xavier | M | 55 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 121 | Corbiau | Paul | M | 61 | renter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 122 | Corbisier | Frédéric | M | 17 | gas-plant fitter | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 123 | Corbisier | Joseph | M | 42 | gas-plant fitter | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 124 | Couillard | Armand | M | 34 | cabinetmaker | Tienne d'Orsy | |

| 125 | Couillard | Auguste | M | 71 | cabinetmaker | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 126 | Coupienne | Camille | M | 32 | baker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 127 | Coupienne | Emile | M | 54 | cobbler | Laurent Wall | |

| 128 | Coupienne | Henri | M | 38 | rattacheur | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 129 | Coupienne | Joseph-Camille | M | 36 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 130 | Coupienne | Joseph | M | 58 | cobbler | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 131 | Coupienne | Victor | M | 51 | brewery worker | Leffe (convent) | |

| 132 | Croin | Lambert | M | 46 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 133 | Culot | Edouard | M | 59 | trader | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 134 | Culot | Florent | M | 24 | entrepreneur | Pré Capelle | |

| 135 | Culot | Gustave | M | 24 | factory worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 136 | Culot | Henri | M | 48 | storekeeper | Bourdon Wall | |

| 137 | Dachelet | Camille | M | 20 | domestic | Pré Capelle | |

| 138 | Dachelet | Zéphyrin | M | 17 | domestic | Pré Capelle | |

| 139 | Dandoy | Gustave | M | 44 | brewery worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 140 | Darville | Arthur | M | 26 | employee | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 141 | Dasty | Désiré | M | 74 | renter | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 142 | Dauphin | Camille | M | 18 | weaver | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 143 | Dauphin | Désiré | M | 35 | storekeeper | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 144 | Dauphin | Joséphine | F | 20 | weaver | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 145 | Dauphin | Léopold | M | 49 | weaver | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 170 | De Muyter | Constantin | M | 60 | storekeeper | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 146 | Defays | Marie | F | 54 | housewife | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 147 | Dehez | Sylvain | M | 43 | agent d'assurances | Paper Mill | |

| 148 | Dehu | Victorien | M | 48 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 149 | Delaey | Arthur | M | 20 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 150 | Delaey | Emile | M | 24 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 151 | Delaey | Camille-Alexis | M | 23 | rattacheur | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 152 | Delaey | Camille-Antoine | M | 48 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 153 | Delaey | Georges | M | 16 | rattacheur | Paper Mill | |

| 154 | Delaey | Philippe | M | 20 | gas worker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 155 | Delaire | Marie | F | 36 | housewife | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 156 | Delcourt | Louis | M | 56 | maneuver | Herbuchenne (?) | |

| 157 | Delieux | Thérèse | F | 38 | housewife | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 158 | Delimoy | Victorine | M | 81 | without profession | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 159 | Dellot | Charles | M | 32 | journalist | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 160 | Dellot | Jules | M | 29 | journalist | Montagne de la Croix | |

| 161 | Deloge | Alphonse | M | 58 | butcher | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 162 | Deloge | Edmond | M | 23 | butcher | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 163 | Deloge | Eugène | M | 15 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 164 | Deloge | Ferdinand | M | 44 | construction foreman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 165 | Delvaux | Henri | M | 54 | piano manufacturer | Alardo farm | |

| 166 | Delvigne | Jules | M | 48 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 167 | Demillier | Arthur | M | 24 | hotel garçon | Saint-Médard | |

| 168 | Demotie | Elisée | M | 41 | doucheur | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 169 | Demotie | Modeste | M | 45 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 171 | Deskeuve | Jean | M | 39 | state roadmender | Bourdon Wall | |

| 172 | Deskeuve | Marie | F | 36 | market gardener | Bourdon Wall | |

| 173 | Dessy | Jules | M | 38 | storekeeper | Paper Mill | |

| 174 | Detinne | Augustine | F | 61 | housewife | Rue des Fossés | |

| 175 | Dewez | François | M | 32 | blacksmith | Pré Capelle | |

| 177 | Didion | Callixte | M | 20 | hotel garçon | Saint-Médard | |

| 176 | Diffrang | Emile | M | 49 | weaver | Bourdon Wall | |

| 178 | Disy | Georges | M | 34 | weaver | Leffe (convent) | |

| 179 | Disy | Jacques | M | 55 | journalist | Leffe (impasse St-Georges) | |

| 180 | Disy | Julien | M | 68 | storekeeper | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 181 | Disy | Luc | M | 35 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 182 | Disy | Vital | M | 48 | weaver | Laurent Wall | |

| 183 | Dobbeleer | Jules | M | 36 | confectioner | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 184 | Dome | Adolphe | M | 48 | professor | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 185 | Domine | Ernest | M | 51 | state roadmender | Bourdon Wall | |

| 187 | Donnay | Léon | M | 36 | house painter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 188 | Donné | Camille | M | 36 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 186 | Dony | Pierre-Joseph Adelin | M | 70 | janitor | Collège communal | |

| 189 | Dubois | Joseph | M | 62 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 190 | Dubois | Xavier | M | 44 | colporteur | Bourdon Wall | |

| 191 | Duchene | Emile | M | 49 | mill fabric driver | Paper Mill | |

| 192 | Duchene | Ernest | M | 55 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 193 | Dufrenne | Renée | F | 37 | housewife | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 200 | Dujeux | François | M | 39 | truck driver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 194 | Dumont | Clémentine | F | 38 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 195 | Dupont | Joseph | M | 8 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 196 | Dupont | Léon | M | 38 | security guard | Bourdon Wall | |

| 197 | Dupont | René | M | 10 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 198 | Dure | Léon | M | 50 | journalist | Bouvignes | |

| 199 | Dury | Emile | M | 49 | cobbler | Bourdon Wall | |

| 201 | Eliet | Arthur | M | 56 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 202 | Eloy | Waldor | M | 37 | teacher | Pré Capelle | |

| 203 | Englebert | Alexis | M | 61 | journalist | Malaise Farm | |

| 204 | Englebert | Victor-Joseph | M | 60 | garçon-brewer | Paper Mill | |

| 205 | Étienne | Auguste | M | 23 | valet parker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 206 | Eugene | Emile | M | 39 | cultivator (domestic) | Mouchenne | |

| 207 | Evrard | Jean-Baptiste | M | 38 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 208 | Fabry | Albert | M | 44 | trader | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 209 | Fallay | Jacques | M | 44 | trader | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 210 | Fastres | François | M | 68 | mason | Promenade de Meuse | |

| 211 | Fastres | Odile | F | 42 | market gardener | Bourdon Wall | |

| 212 | Fauconnier | Auguste | M | 39 | storekeeper | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 213 | Fauconnier | Théophile | M | 44 | employee (Leffe factory) | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 214 | Fauquet | Antoine-Zéphyrin | M | 22 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 215 | Fauquet | Louis | M | 30 | hairdresser | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 216 | Fauquet | Théophile | M | 52 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 217 | Fecherolle | Henri | M | 40 | plombier | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 218 | Fecherolle | Henri | M | 46 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 219 | Fecherolle | Joseph | M | 33 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 220 | Fecherolle | Marcel | M | 17 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 221 | Feret | Alphonse | M | 38 | valet parker | Laurent Wall | |

| 222 | Feret | Louis | M | 16 | weaver | Laurent Wall | |

| 223 | Ferre | Pierre | M | 63 | religious | Place de Meuse | |

| 224 | Fevrier | Eugène | M | 33 | storekeeper | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 225 | Fevrier | Georges | M | 31 | ouvrier tanneur | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 226 | Fievet | Arnould | M | 72 | without profession | Devant-Bouvignes | |

| 227 | Fievez | Auguste | M | 59 | house painter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 228 | Fievez | Camille | M | 55 | house painter | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 229 | Finfe | Jean | M | 23 | factory worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 230 | Finfe | Joseph | M | 60 | quarry worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 231 | Finfe | Julien | M | 32 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 232 | Firmin | Alexis | M | 19 | dressmaker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 233 | FIRMIN | Joseph-Léon | M | 43 | dressmaker | Montagne de la Croix | |

| 234 | Firmin | Joseph | M | 16 | apprenti-mechanic | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 235 | Firmin | Léon | M | 18 | typographer (dressmaker) | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 236 | Fisetie | Camille | M | 50 | trader | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 237 | Fivet | Auguste | M | 36 | accountant | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 238 | Fivet | Ferdinand | M | 25 | cabinetmaker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 239 | Fivet | Mariette | F | 3 weeks | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 240 | Flostroy | Emile | M | 31 | baker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 241 | Fondaire | Ernest | M | 46 | stone mason | Paper Mill | |

| 242 | Fondaire | Marcel | M | 14 | yes | Paper Mill | |

| 243 | Fondaire | Pauline | F | 18 | factory worker | Fonds de Leffe | |

| 244 | Fondaire | Robert | M | 16 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 245 | Fonder | François | M | 62 | trader | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 246 | Fonder | Jean-Baptiste | M | 31 | architecte | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 247 | Fontaine | Désiré | M | 32 | pianiste | Laurent Wall | |

| 248 | Gaudinne | Alphonse | M | 47 | mason | Bourdon Wall | |

| 249 | Gaudinne | Edouard | M | 24 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 250 | Gaudinne | François | M | 54 | carpenter | Paper Mill | |

| 251 | Gaudinne | Florent | M | 7 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 252 | Gaudinne | Joseph | M | 71 | drainer | Herbuchenne | |

| 253 | Gaudinne | Jules | M | 16 | carpenter | Paper Mill | |

| 254 | Gaudinne | René | M | 18 | Quartier de « La Dinantaise » | ||

| 255 | Gelinne | Georges | M | 27 | dressmaker (railway worker) | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 256 | Gelinne | Gustave | M | 28 | bodybuilder | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 257 | Genet | Alfred | M | 35 | cook | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 258 | Genon | Gilda | M | 19 months | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 259 | Genot | Félicien | M | 64 | iron turner | Leffe (convent) | |

| 260 | Georges | Adelin | M | 34 | carpenter | La « Cité » | |

| 261 | Georges | Alexandre | M | 36 | carpenter | Montagne de la Croix | |

| 262 | Georges | Alfred | M | 36 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 263 | Georges | Amand | H | 53 | employee | Leffe (convent) | |

| 264 | Georges | Apolline | F | 54 | housewife | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 265 | Georges | Auguste | M | 58 | chauffeur to the gas factory | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 266 | Georges | Auguste | M | 39 | dressmaker | Place d'Armes and prison | |

| 267 | Georges | Camille | M | 36 | baker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 268 | Georges | Henri | M | 68 | locksmith | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 269 | Georges | Joseph | M | 44 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 270 | Georges | Louis | M | 28 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 271 | Geudvert | Albert | M | 17 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 272 | Geudvert | Emile | M | 54 | cobbler | Paper Mill | |

| 273 | Giaux | Victor | M | 49 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 274 | Gillain | Alfred | M | 64 | mechanic | Rue des Basses Tanneries | |

| 275 | Gillain | Robert | M | 14 | yes | weaver | Neffe-Dinant |

| 276 | Gillet | Jules | M | 28 | marble mason | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 277 | Gillet | Omer | M | 45 | blacksmith | Bouvignes | |

| 278 | Goard | François | M | 60 | without profession | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 279 | Goard | Marie-Louise | F | 5 | yes | Rue Grande (?) | |

| 280 | Godain | Clément | M | 48 | sand moulder | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 281 | Godinne | Georges | M | 17 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 282 | Goffaux | Marcel | M | 18 | rattacheur | Paper Mill | |

| 283 | Goffaux | Pierre | M | 48 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 284 | Goffin | Eugène | M | 47 | brewery worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 285 | Goffin | Eugène | M | 15 | domestic | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 286 | Gonze | François | M | 25 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 287 | Gonze | Léopold | M | 65 | cobbler | Paper Mill | |

| 288 | Grandjean | Désiré | M | 56 | charpentier | Fonds de Leffe | |

| 289 | Grenier | Joseph | M | 46 | journalist | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 290 | Grigniet | François | M | 26 | employee | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 291 | Guerry | Joseph | M | 31 | employee (district police station) | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 292 | Guillaume | Charles | M | 38 | trader | Fonds des Pèlerins | |

| 293 | Guillaume | Emile | M | 44 | teacher | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 294 | Gustin | Edmond | M | 10 | yes | schooler | Neffe (aqueduct) |

| 295 | Gustin | Marguerite | F | 20 | seamstress | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 296 | Habran | Emile | M | 31 | cooper | Paper Mill | |

| 297 | Halloy | Gustave | M | 48 | mason | Herbuchenne | |

| 298 | Hamblenne | Catherine | F | 51 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 299 | Hamblenne | Hubert | M | 45 | carpenter | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 300 | Hansen | Alexis | M | 54 | maneuver | Impasse Saint-Georges | |

| 301 | Hardy | Edouard | M | 50 | weaver | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 302 | Hardy | Octave | M | 39 | basket maker | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 303 | Hastir | Thérèse | F | 80 | housewife | La « Cité » | |

| 304 | Haustenne | Emile | M | 30 | quarry worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 305 | Hauteclaire | Henri | M | 44 | quarry worker | Herbuchenne | |

| 306 | Hautot | Emile | M | 30 | cultivator | Herbuchenne (Alardo farm) | |

| 307 | Hautot | Joseph | M | 34 | cultivator | Près de Bonair | |

| 308 | Henenne | René | M | 21 | weaver | Rocher Bayard | |

| 309 | Hennuy | Alexis | M | 43 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 310 | Hennuy | Georges | M | 14 | yes | factory worker | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe |

| 311 | Hennuy | Gustave | M | 36 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 312 | Hennuy | Jules | M | 18 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 313 | Hennuy | Marcel | M | 15 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 314 | Henrion | Alphonse | M | 41 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 315 | Henry | Camille | M | 30 | factory worker | Devant-Bouvignes | |

| 316 | Henry | Désiré | M | 27 | threader | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 317 | Herman | Alphonse | M | 48 | house painter | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 318 | Herman | Joseph | M | 29 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 319 | Herman | Juliette | F | 13 | yes | schooler | Neffe-Anseremme |

| 320 | Hiernaux | Jules | M | 41 | confectioner (baker) | Laurent Wall | |

| 321 | Himmer | Remy | M | 65 | factory manager | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 322 | Hopiard | Emile | M | 29 | commerce employee | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 323 | Hotielet | Arthur | M | 36 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 324 | Houbion | Eugène | M | 76 | boatman | Rocher Bayard | |

| 325 | Houbion | Jules | M | 50 | cooper | Sœurs de la Charité | |

| 326 | Huberland | Camille | M | 28 | employee | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 327 | Hubert | Octave | M | 36 | police officer | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 328 | Hubin | Emile | M | 77 | ceiling operator | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 339 | Jacqmain | Auguste | M | 51 | dressmaker | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 329 | Jacquet | Alexandre | M | 66 | weaver | Leffe (convent) | |

| 330 | Jacquet | Camille | M | 29 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 331 | Jacquet | Gaston | M | 41 | baker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 332 | Jacquet | Gustave-Edmond | M | 63 | miller | Pré Capelle | |

| 333 | Jacquet | Gustave | M | 23 | cultivator | Pré Capelle | |

| 334 | Jacquet | Henri | M | 55 | valet parker (weaver) | Paper Mill | |

| 335 | Jacquet | Joseph | M | 45 | garde-chasse | Montagne de la Croix | |

| 336 | Jacquet | Jules | M | 65 | traveling salesman | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 337 | Jacquet | Louis | M | 36 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 338 | Jacquet | Victor | M | 60 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 340 | Jassogne | Léon | M | 26 | cobbler | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 341 | Jassogne | Théodorine | F | 27 | factory worker | Aux Caracolles | |

| 342 | Jaumaux | Camille | M | 44 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 343 | Jaumaux | Georges | M | 18 | factory worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 344 | Jaumot | Alexandre | M | 36 | journalist | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 345 | Junius | Joseph | M | 43 | mechanic | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 346 | Junius | Prosper | M | 51 | professor | Laurent Wall | |

| 347 | Kestemont | François | M | 21 | café garçon | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 348 | Kinif | Joseph | M | 61 | baker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 349 | Kinique | Edmond | M | 57 | storekeeper | Bourdon Wall | |

| 350 | Kinique | Joseph | M | 19 | diamond dealer | Bourdon Wall | |

| 351 | Kinique | Jules | M | 13 | yes | student | Bourdon Wall |

| 352 | Kinique | Louise | F | 21 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 353 | Laffut | Isidore | M | 61 | construction foreman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 354 | Laforet | Adolphe | M | 23 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 355 | Laforet | Alphonse | M | 34 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 356 | Laforet | Camille-Alphonse | M | 55 | brewery worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 357 | Laforet | Camille-Victor | M | 18 | brewery worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 358 | Laforet | Joseph | M | 37 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 359 | Laforet | Xavier | M | 31 | brewery worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 360 | Lagneau | Ernest | M | 67 | factory worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 361 | Lahaye | Eugène | M | 47 | baker | Laurent Wall | |

| 362 | Lahaye | Joseph | M | 55 | baker | Leffe (convent) | |

| 363 | Laloux | Charlotte | F | 32 | housewife | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 364 | Laloux | Victor-Lambert | M | 76 | stone mason | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 365 | Lamand | Marie | F | 31 | housewife | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 366 | Lambert | François | M | 45 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 367 | Lambert | Victor | M | 43 | truck driver (brewer) | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 368 | Lamberty | Louis | M | 32 | cooper | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 369 | Lamour | Emile | M | 27 | cabinetmaker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 370 | Laurent | Joseph | M | 56 | trader | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 371 | Laurent | Marie | F | 57 | journalist | Saint-Médard | |

| 372 | Laverge | Mélanie | F | 38 | housewife | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 373 | Lebrun | Alphonse | M | 33 | dressmaker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 374 | Lebrun | Henri | M | 48 | postal worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 375 | Lebrun | Joseph-François | M | 19 | dressmaker | Place d'Armes and prison | |

| 376 | Lebrun | Joseph | M | 59 | journalist | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 377 | Leclerc | Olivier | M | 53 | cultivator | Pré Capelle | |

| 378 | Leclerc | Pierre | M | 25 | cultivator | Pré Capelle | |

| 379 | Lecocq | Louis | M | 53 | organist | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 380 | Lecomte | Joséphine | F | 73 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 381 | Ledent | Gilles | M | 29 | terrassier | Rocher Bayard | |

| 382 | Legros | Marie | F | 51 | trader | Place d'Armes and prison | |

| 383 | Lejeune | Charles | M | 20 | wood turner | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 384 | Lemaire | Camille | M | 17 | butcher | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 385 | Lemaire | Jean | M | 41 | dressmaker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 386 | Lemaire | Jules | M | 42 | butcher | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 387 | Lemer | Charles | M | 13 | yes | schooler | Anseremme (Brasserie) |

| 388 | Lemer | François | M | 53 | ceiling operator | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 389 | Lemineur | Joséphine | F | 72 | without profession | Aux Caracolles | |

| 390 | Lemineur | Jules | M | 44 | locksmith | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 391 | Lempereur | Jeanne | F | 16 | telephonist | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 392 | Lenain | Théodule-Jean-Joseph | M | 40 | construction foreman (Leffe factory) | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 393 | Lenain | Théodule | M | 17 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 394 | Lenel | Auguste | M | 21 | hairdresser | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 395 | Lenoir | Victor | M | 58 | journalist | Saint-Médard | |

| 396 | Leonard | Françoise | F | 25 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 397 | Lepage | Camille | M | 53 | valet parker (domestic) | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 398 | Lepas | Louise | F | 16 | factory worker | Saint-Médard | |

| 399 | Libert | Léon | M | 21 | factory worker | Dry les Wennes | |

| 400 | Libert | Nestor | M | 30 | pig farmer | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 401 | Limet | Jules | M | 46 | weaver | Leffe (rue St-Georges) | |

| 402 | Lion | Alexis | M | 41 | house painter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 403 | Lion | Amand | M | 63 | clockmaker | Rue Sax | |

| 404 | Lion | Arthur | M | 26 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 405 | Lion | Charles | M | 40 | dressmaker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 406 | Lion | Joseph | M | 28 | traveling salesman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 407 | Lion | Joseph | M | 69 | typographer | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 408 | Lion | Jules | M | 27 | clockmaker | Rue Sax | |

| 409 | Lissoir | Camille | M | 33 | butcher (cooper) | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 410 | Lissoir | Pierre | M | 71 | cultivator | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 411 | Longville | Félix | M | 63 | police commissioner | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 412 | Looze | Marie | F | 43 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 413 | Louis | Benjamin | M | 15 | weaver | Laurent Wall | |

| 414 | Louis | Désiré | M | 55 | construction foreman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 415 | Louis | Désiré | M | 20 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 416 | Louis | Vital | M | 18 | factory worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 417 | Louis | Xavier | M | 51 | construction foreman (Leffe factory) | Laurent Wall | |

| 418 | Lupsin | Alphonse | M | 59 | quarry worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 419 | Maillen | Marie-Thérèse | F | 42 | trader | Hauteurs de la rive droite | |

| 420 | Manteau | Edmond | M | 70 | cabaretier | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 421 | Maquet | Elvire | F | 22 | factory worker | Aux Caracolles | |

| 422 | Marchal | Camille | M | 44 | weaver | Leffe (convent) | |

| 423 | Marchal | Henri | M | 18 | dressmaker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 424 | Marchal | Jules | M | 47 | storekeeper | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 425 | Marchal | Michel | M | 50 | dressmaker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 426 | Marchot | Gilda | F | 2 | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 427 | Marchot | Joseph | M | 46 | wheelwright | Bourdon Wall | |

| 428 | Maretie | Hubert | M | 38 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 429 | Maretie | Joseph | M | 42 | construction foreman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 430 | Marine | Joseph | M | 55 | brewery worker | Montagne de la Croix | |

| 431 | Marlier | Flore | F | 58 | greengrocer | Rue des Fossés | |

| 432 | Marsigny | Madeleine | F | 22 | without profession | Les Rivages | |

| 433 | Martin | Alphonse | M | 62 | farm domestic | Herbuchenne | |

| 434 | Martin | Henriette | F | 19 | factory worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 435 | Martin | Joseph | M | 23 | factory worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 436 | Martin | Marie | F | 17 | factory worker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 437 | Martin | Pierre | M | 60 | knifemaker | Bourdon Wall | |

| 438 | Masson | Camille | M | 42 | construction foreman (Leffe factory) | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 439 | Masson | Victor | M | 39 | construction foreman (Leffe factory) | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 440 | Matagne | Clotilde | F | 71 | without profession | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 441 | Materne | Jules | M | 70 | market gardener | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 442 | Mathieu | Emile | M | 51 | mechanic | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 443 | Mathieux | Auguste | M | 67 | commissionnaire | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 444 | Mathieux | Eugène | M | 69 | brewery worker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 445 | Mathieux | François | M | 23 | dressmaker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 446 | Maudoux | Armand | M | 46 | gluer | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 447 | Maurer | Octave | M | 31 | brewery worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 448 | Maury | Alphonse | M | 48 | blacksmith | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 449 | Mazy | Antoine | M | 49 | carpenter | Fonds de Leffe | |

| 450 | Mazy | Joseph-Julien | M | 55 | brewery worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 451 | Mazy | Lucien | M | 26 | weaver | Malaise Farm | |

| 452 | Mazy | Ulysse | M | 41 | dressmaker | Paper Mill | |

| 453 | Menu | Hubert | M | 39 | longshoreman | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 454 | Mercenier | Nicolas | M | 72 | domestic | Collège communal | |

| 455 | Meura | Alfred | M | 40 | cobbler | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 456 | Meurat | Emile | M | 7 | yes | schooler | Neffe (aqueduct) |

| 457 | Meurat | Eva | F | 6 | yes | schooler | Neffe (aqueduct) |

| 458 | Meurat | Victor | M | 2.5 | yes | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 459 | Meurisse | Marcelline | F | 59 | housewife | Rocher Bayard | |

| 461 | Michel | Emile | M | 27 | dressmaker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 462 | Michel | Hyacinthe | M | 57 | journalist | La « Cité » | |

| 463 | Michel | Jules | M | 39 | storekeeper | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 464 | Michel | Lambert | M | 63 | baker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 465 | Michel | Léon-Victor | M | 36 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 466 | Michel | Léon-Louis | M | 49 | rag merchant | Au Couret | |

| 470 | Migeotte | Adolphe | M | 62 | cultivator | Paper Mill | |

| 471 | Migeotte | Alphonse | M | 15 | rattacheur | Paper Mill | |

| 472 | Migeotte | Camille | M | 19 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 473 | Migeotte | Constant | M | 14 | yes | Paper Mill | |

| 474 | Migeotte | Emile | M | 32 | valet parker (pig farmer) | Paper Mill | |

| 475 | Migeotte | Henri | H | 16 | rattacheur | Paper Mill | |

| 476 | Migeotte | Louis | M | 50 | threader | Paper Mill | |

| 467 | Milcamps | Jules | M | 36 | assistant clerk | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 468 | Milcamps | Lucien | M | 68 | former lock keeper | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 469 | Minet | Marie | F | 45 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 460 | MlChat | Andrée | F | 3 | yes | Place d'Armes and prison | |

| 477 | Modave | Nestor | M | 40 | cultivator | Pré Capelle | |

| 478 | Monard | Jules | M | 79 | renter | Pont d'Amour | |

| 479 | Monin | Alphonse | M | 14 | yes | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe |

| 480 | Monin | Arthur | M | 25 | weaver | Laurent Wall | |

| 481 | Monin | Charles | M | 26 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 482 | Monin | Eugène | M | 19 | factory worker | Laurent Wall | |

| 483 | Monin | Félix | M | 53 | threader | Paper Mill | |

| 484 | Monin | Fernand | M | 55 | trader | Place de Meuse | |

| 485 | Monin | Jean-Baptiste | M | 47 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 486 | Monin | Henri | M | 28 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 487 | Monin | Hyacinthe | M | 53 | weaver | Laurent Wall | |

| 488 | Monin | Jules | M | 40 | brewer | Laurent Wall | |

| 489 | Monin | Nicolas | M | 56 | baker | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 490 | Monin | Pierre | M | 27 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 494 | Monty | Alexandre | M | 39 | re-mortar | Paper Mill | |

| 495 | Morelle | Joseph | M | 69 | charron | Bourdon Wall | |

| 496 | Morelle | Jules | M | 17 | student | Bourdon Wall | |

| 497 | Morelle | Marguerite | F | 11 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 498 | Mossiat | Frédéric | M | 27 | confectioner | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 499 | Mossiat | Jules | M | 38 | sommelier | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 500 | Mosty | Eugène | M | 58 | brewery worker | Laurent Wall | |

| 501 | Moussoux | Léon | M | 55 | hotelier | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 491 | Mouton | Jules | M | 48 | trader | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 492 | Mouton | Justine | F | 76 | housewife | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 493 | Mouton | René | M | 19 | employee | Paper Mill | |

| 502 | Naus | Charles | M | 57 | mechanic | Leffe (rue Longue) | |

| 503 | Naus | Joséphine | F | 67 | housewife | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 504 | Nepper | Emile-Thomas | M | 16 | student | Paper Mill | |

| 505 | Nepper | Emile | M | 41 | butcher | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 506 | Nepper | Louis | M | 42 | cultivator | Paper Mill | |

| 507 | Neuret | Auguste | M | 22 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 508 | Nicaise | Gustave | M | 77 | renter | Laurent Wall | |

| 509 | Nicaise | Léon | M | 75 | renter | Laurent Wall | |

| 510 | Ninite | Nelly | F | 24 | housewife | Les Rivages | |

| 511 | Noel | Alexandre | M | 40 | ceiling operator | Laurent Wall | |

| 512 | Ory | Louis-Joseph | M | 27 | baker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 514 | Pairoux | Alfred | M | 45 | butcher | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 513 | Panier | Fernand | M | 38 | pharmacist | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 515 | Paquet | Armand-Joseph | M | 30 | boilermaker (labourer) | Paper Mill | |

| 516 | Paquet | Armand-François | M | 27 | wood turner | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 517 | Paquet | Émilie | F | 76 | housewife | Indéterminé | |

| 518 | Paquet | Floris | M | 22 | threader | Dry les Wennes | |

| 519 | Paquet | Louis | M | 34 | pharmacist | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 520 | Paquet | Marie | F | 37 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 521 | Paquet | Marie-Joséphine | F | 19 | without profession | Bourdon Wall | |

| 522 | Patard | Marie | F | 57 | housewife | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 523 | Patigny | Jean-Baptiste | M | 43 | truck driver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 524 | Patigny | Henri | M | 47 | hotel garçon | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 525 | Pecasse | Florent | M | 56 | weaver (tannery worker) | Entrée des Fonds de Leffe | |

| 526 | Pecasse | Hermance | F | 38 | store manager | Rue Grande | |

| 527 | Pecasse | Joseph | M | 38 | quarry worker | Rue du faubourg Saint-Nicolas | |

| 528 | Peduzy | Joseph | M | 50 | cooper | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 529 | Perez Villazo | Vicente | M | 20 | domestic (cook) | Collège communal | |

| 530 | Perreu | Nicolas-Urbain | M | 40 | religious | Leffe (aqueduct) | |

| 531 | Petit | Joseph | M | 17 | factory worker | La « Cité » | |

| 532 | Petit | Noël | M | 12 | yes | La « Cité » | |

| 533 | Philippart | Jean | M | 59 | clothes cutter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 534 | Pierard | Olivier | M | 67 | renter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 535 | Pierre | Adrien-Joseph | M | 73 | journalist | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 536 | Pietie | Adrien-Victor | M | 20 | traveling salesman | Leffe (impasse St-Georges) | |

| 537 | Pietie | Joseph | M | 45 | baker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 538 | Pinsmaille | Adèle | F | 44 | market gardener (seamstress) | Bourdon Wall | |

| 539 | Pinsmaille | Charles | M | 34 | typographer | Quartier de « La Dinantaise » | |

| 540 | Pinsmaille | Marie | F | 49 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 542 | Pire | Antoine | M | 21 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 543 | Pire | Emile | M | 53 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 544 | Piret | Joseph | M | 47 | factory worker | Paper Mill | |

| 545 | Piret | Victor | M | 63 | postal worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 546 | Pirlot | Félicie | F | 67 | market gardener | Bourdon Wall | |

| 547 | Pirot | Joseph | M | 38 | quilter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 548 | Pirson | Alexandre | M | 52 | brewery worker | Devant-Bouvignes | |

| 549 | Pirson | Narcisse | M | 47 | postal worker | Route de Namur | |

| 541 | Pl Raux | Adelin | M | 32 | cattle merchant | Pré Capelle | |

| 550 | Polita | Joachim | M | 32 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 551 | Polita | Léon | M | 37 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 552 | Pollet | Auguste | M | 43 | market gardener (carrier) | Bourdon Wall | |

| 553 | Pollet | Edouard | M | 15 | weaver | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 554 | Pollet | Eugénie | F | 36 | seamstress | Bourdon Wall | |

| 555 | Pollet | Louise | F | 46 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 556 | Pollet | Nelly | F | 12 months | yes | Bourdon Wall | |

| 557 | Poncelet | Gustave | M | 22 | gas worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 558 | Poncelet | Henri | M | 61 | journalist | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 559 | Poncelet | Henriette | F | 54 | housewife | Bourdon Wall | |

| 560 | Poncelet | Pierre | M | 32 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 561 | Poncelet | Victor | M | 41 | industriel (dinandier) | Leffe (rue Longue) | |

| 562 | Poncin | Jules | M | 48 | stone mason | Rue de la Grêle | |

| 563 | Ponthieux | François | M | 84 | gardener | Indéterminé | |

| 564 | Prignon | Octave | M | 40 | municipal collector | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 565 | Questiaux | Ferdinand | M | 51 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 566 | Quoilin | Anselme | M | 53 | employee | Laurent Wall | |

| 567 | Quoilin | Anselme | M | 28 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 568 | Quoilin | Désiré | M | 59 | construction foreman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 569 | Quoilin | Fernand | M | 33 | employee | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 570 | Quoilin | Joseph | M | 56 | construction foreman | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 571 | Rase | Emma | F | 50 | without profession | Bourdon Wall | |

| 572 | Rasseneux | Léopoldine | F | 19 | factory worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 573 | Ravet | François-Eugène | M | 50 | entrepreneur (carpenter) | Paper Mill | |

| 574 | Ravet | François-Albert | M | 37 | wood turner | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 575 | Ravet | Joseph | M | 39 | wood turner | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 576 | Remacle | Victor | M | 68 | journalist | Fonds de Leffe | |

| 577 | Remy | Eudore | M | 39 | medic | Rue Sax | |

| 578 | Renard | Albert | M | 27 | pig farmer | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 579 | Rifflart | Nestor | M | 55 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 580 | Roba | Simon-Joseph | M | 48 | deputy commissioner of police | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 581 | Rodrigue | Jean | M | 5 months | yes | Les Rivages | |

| 582 | Rolin | Jules | M | 43 | employee (croupier) | Bourdon Wall | |

| 583 | Romain | Camille | M | 40 | commissionnaire | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 584 | Romain | Henri | M | 30 | farm worker | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 585 | Ronv(E)Aux | Emile | M | 66 | carpenter | Paper Mill | |

| 586 | Ronv(E)Aux | Joseph | M | 38 | carpenter | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 587 | Roucoux | Edmond | M | 17 | cobbler | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 588 | Roucoux | Maurice | M | 16 | weaver | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 589 | Rouelle | Marcelline | F | 40 | housewife | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 590 | Rouffiange | Charles | M | 68 | mason | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 591 | Rouffiange | Désiré | M | 32 | weaver | Paper Mill | |

| 592 | Roulin | Germaine | F | 20 | lingerie | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 593 | Roulin | Henriette | F | 12 | yes | schooler | Neffe-Anseremme |

| 594 | Roulin | Joseph | M | 23 | storekeeper | Bourdon Wall | |

| 595 | Sanglier | Joseph | M | 37 | employee (factory worker) | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 596 | Sarazin | Hortense | F | 59 | housewife | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 597 | Sauvage | Auguste | M | 22 | employee | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 598 | Sauvage | Joseph | M | 28 | weaver | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 599 | Schelbach | Jules | M | 59 | bourrelier | Les Rivages | |

| 600 | Schram | Arthur | M | 28 | weaver | Pont d'Amour | |

| 601 | Schram | Egide | M | 64 | wood turner | Pont d'Amour | |

| 602 | Seguin | Jules | M | 67 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 603 | Seha | Vital | M | 59 | dressmaker | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 604 | Servais | Adolphe | M | 63 | former municipal secretary | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 605 | Servais | Georges | M | 26 | cabinetmaker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 606 | Servais | Léon | M | 23 | baker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 607 | Servais | Louis | M | 18 | wood turner | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 608 | Serville | Guillaume | M | 51 | farm domestic | Rondchêne | |

| 609 | Sibret | Alfred | M | 18 | cultivator | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 610 | Simon | Auguste | M | 22 | basket maker | Place Saint-Nicolas | |

| 611 | Simon | Étienne | M | 78 | renter | Laurent Wall | |

| 612 | Simon | Florian | M | 39 | factory worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 613 | Simon | Léon | M | 55 | house painter | Tienne d'Orsy | |

| 614 | Simonet | Arthur | M | 47 | employee (weaver) | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 615 | Simonet | Félix | M | 72 | renter | Laurent Wall | |

| 616 | Sinzot | Léon | M | 43 | railway worker | Laurent Wall | |

| 617 | Solbrun | Elie | M | 40 | valet parker (baker) | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 618 | Somme | Adelin | M | 25 | electrician | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 619 | Somme | Constant | M | 39 | carpenter | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 620 | Somme | Grégoire | M | 48 | cobbler | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 621 | Somme | Hyacinthe | M | 26 | baker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 622 | Somme | Léon | M | 18 | electrician | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 623 | Soree | Vital | M | 15 | factory worker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 624 | Sovet | Emile | M | 32 | cook | Bourdon Wall | |

| 625 | Struvay | Claire | F | 2 | oui | Bourdon Wall | |

| 626 | Struvay | René | M | 11 | yes | schooler | Bourdon Wall |

| 627 | Taton | Ferdinande | F | 62 | housewife | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 628 | Texhy | Joseph | M | 39 | weaver | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 629 | Thianche | Désiré | M | 30 | warehouseman (foundry worker) | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 630 | Thibaux | Maurice-Edmond | M | 15 | student | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 631 | Thirifays | Marie-Thérèse-Adèle | F | 57 | without profession | Leffe | |

| 632 | Thirifays | Lambert | M | 33 | renter | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 633 | Thomas | Joseph | M | 33 | baker | Leffe (convent) | |

| 634 | Toussaint | Céline | F | 33 | housewife | Neffe (aqueduct) | |

| 635 | Toussaint | Joseph | M | 56 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 636 | Toussaint | Louis | M | 32 | gluer | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza or surroundings | |

| 637 | Toussaint | Marie | F | 66 | housewife | Pont d'Amour | |

| 638 | Toussaint | Victor | M | 24 | fountain engineer | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 639 | Trinteler | Eugène | M | 47 | fish merchant | Place de Meuse | |

| 640 | Van Buggenhout | Jean | M | 37 | concrete worker | Abbaye Notre-Dame de Leffe Plaza | |

| 641 | Vandeputie | Henriette | F | 21 | servant | Bouvignes | |

| 642 | Vanderhaegen | Arthur | M | 36 | weaver | Bourdon Wall | |

| 643 | Vanheden | Pauline | F | 55 | trader | Place de Meuse | |

| 644 | Vaugin | Augustin-Arille | M | 64 | pig farmer | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 645 | Verenne | Arthur-Antoine | M | 24 | weaver | Entrance to Fonds de Leffe | |

| 646 | Verenne | Arthur-Gilles | M | 48 | valet parker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 647 | Verenne | Marcel | M | 17 | cabinetmaker | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 648 | Verenne | Georges | M | 20 | employee | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 649 | Vilain | Alexandre | M | 40 | trader | Rue Saint-Jacques | |

| 650 | Vilain | Fernand | M | 34 | professor de musique | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 651 | Vinstock | Fernand | M | 25 | weaver | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 652 | Vinstock | Frédéric | M | 57 | valet parker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 653 | Vinstock | Jules | M | 15 | student | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 654 | Vinstock | Louis | M | 19 | weaver | Neffe-Dinant | |

| 655 | Warnant | Alzir | M | 34 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 656 | Warnant | Félix | M | 24 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 657 | Warnant | Pierre | M | 24 | showman | Leffe (impasse St-Georges) | |

| 658 | Warnant | Urbain | M | 30 | journalist | Paper Mill | |

| 659 | Wartique | Rachel | F | 20 | without profession | Neffe-Anseremme | |

| 660 | Warzee | Octave | M | 47 | construction foreman | Bourdon Wall | |

| 661 | Wasseige | Jacques | M | 19 | student | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 662 | Wasseige | Pierre | M | 20 | employee | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 663 | Wasseige | Xavier | M | 43 | banker | Tschoffen Wall | |

| 664 | Watrisse | Emile | M | 28 | weaver | Bourdon Wall | |

| 665 | Wilmotie | Camille | M | 23 | streetcar conductor (cashier) | Impasse Saint-Roch | |

| 666 | Winand | Antoine-Ignace | M | 36 | dressmaker | Rue Saint-Pierre | |

| 667 | Winand | Victor | M | 30 | cobbler | Rue Saint-Pierre | |