Marion Carpenter

Marion A. Carpenter | |

|---|---|

Carpenter c. 1949 | |

| Born | March 6, 1920 |

| Died | October 29, 2002 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | photographer, nurse |

| Years active | 1942–1984 |

| Known for | pioneer press photographer, first woman White House press photographer |

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

Marion A. Carpenter (March 6, 1920 – October 29, 2002), was the first woman national press photographer to cover Washington, D.C. and the White House, and to travel with a US President. In 1951, Carpenter returned to St. Paul, Minnesota, where she worked as a nurse to support her mother and son. While she did some photography, by her death at age 82, she was little known in the national memory. Since her death, there has been recognition of Carpenter as a pioneer.

Family and early career

Carpenter was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, the daughter of Lillian B. Marion of Minnesota and Harry Carpenter of Avery County, North Carolina. Her father Harry Carpenter moved from North Carolina to work as a laborer in Minnesota, where he met Lillian. They married and settled in St. Paul. As a girl, Marion Carpenter went to local schools and at first planned to be a nurse.[1]

Her paternal Carpenter family were descended from Matthias Carpenter (a German immigrant originally named Zimmermann) of North Carolina. He was born ca. 1750-1755 and died in 1835 in Ashe County, North Carolina (now part of Watauga County, North Carolina).[1][2] Carpenter worked as a nurse from 1942 to 1944. In her off-duty hours from study and work, she had joined the St. Paul Camera Club, where she learned the basics of photography. She became interested in news photography.[1][3]

Photography career

In 1944, Carpenter moved to Washington D.C., where she started working for the Washington Times-Herald. She next joined the International News Photo (INP) syndicate as a special assignment photographer.[1][4][5] In addition to her INP work, she did freelance portraits of senators and representatives.[6] Described as "an athletic brunette", she was herself sometimes the subject of photos.[7]

Her work with the INP syndicate was a factor in winning a highly coveted White House job in 1945,[4] through which she soon developed a professional and cordial relationship with U.S. President Harry S. Truman. She made her mark in Washington "as a photographer of talent and temperament."[1] She became the first woman member of the White House News Photographers Association.[8] She was the only woman press photographer to travel with President Truman on a daily basis.[9]

Carpenter was informally called "the Camera Girl" and "the Photographer Girl" in Washington circles.[10] She resisted being "condescended to by the old men's club" and kept her spirit.[1] In 1946, she told a reporter, "You have to be able to take the guff," after she won an award for a photo of Truman's playing the piano for Lauren Bacall.[4] At the time, despite Carpenter's membership in the White House Photographers Association, women were not allowed at the annual dinners with the president. This policy did not change until 1962.[11]

Carpenter also had pictures published in Life, the photo-journalism magazine which was very popular from the 1940s into the 1960s. For instance, in the May 23, 1949 issue of Life, Carpenter had nine of the twelve pictures in the article on E. George Luckey, who had been a member of the 39th District in the California State Legislature[12]

Marriage and family

Some have speculated that Marion may have had an affair during her time in Washington. When this affair was exposed, she lost her White House job.[9]

Later she married a career Naval officer and moved with him to the West Coast. After she was hospitalized from physical abuse, she ended the marriage and divorced him.[5][9]

Carpenter returned to Washington and began picking up the pieces of her photography career. In 1949, she met the radio announcer John Anderson. They married that year and Carpenter photographed their cross-country trip.[13] They moved to Denver, Colorado where she gave birth to her only child, Mjohn R. Anderson. But this marriage also had problems. By late 1951, when Carpenter was 31, her second marriage and her press photographer career had both ended.[1][9][14]

Later life

Carpenter's later life is not well known.[5] She returned to St. Paul from Denver and worked as a nurse. During the 1950s, she rejoined the St. Paul Camera Club[3] and later opened a wedding photography business.[9] She supported her mother until her death in the 1970s. She also raced homing pigeons and showed German shepherds.[9]

She appeared to be solely responsible for her son Mjohn. In 1968, he graduated from Harding High School. After leaving home, he had his own struggles. He moved west and Carpenter never saw him again. She became a semi-recluse; a very private person, who seldom discussed her past life.[9]

In 1997, the City of St. Paul condemned and tore down her house at 1032 Conway Street, on the east side of the city. Carpenter bought a small house at 1058 Margaret Street with her remaining funds and lived on a small social security pension.[1]

Death

Carpenter died of natural causes; the official primary cause was emphysema.[15] She died at home, nearly destitute, and alone except for her Rottweiler. The closest of what were casual friends recalled that she had a son and led an effort to find him.[1] A distant elderly cousin, found in Maine, authorized one of her friends to act as the executor of her estate.

Carpenter's treasured photography equipment, including over a dozen of her cameras, developers, diffusers and lights, her pictures, and few other possessions were sold at an estate sale in March 2003 by her son Mjohn who had finally been reached by friends and told of his mother's death.[1][10] Several of the older cameras are historical items that form a physical legacy.[15] Her ashes, along with those of her mother, were scattered on a farm between Villard and Glenwood, Minnesota, where she had spent summers as a child.[1] This was done by her son Mjohn, who also donated many of her photographs to the Truman Library in Independence, MO.[10]

Legacy

"She sounds like the type of woman upon whose shoulders we all stand," noted Susy Shultz, president of the Journalism and Women Symposium, when commenting on Marion Carpenter's death.[9]

The St. Paul Camera Club established an annual "Marion Carpenter Award" in her honor for the best monochrome photojournalism print, also known as the "Annual Monochrome Photojournalism Print Award."[3]

Marion Carpenter was not covered in the early annals of women's studies. It may be that she was ahead of her time and her Washington career too brief.[1] Ramona Rush's Seeking Equity for Women in Journalism and Mass Communication Education: A 30-Year Update (2003) describes Carpenter in the preface as a "newly found pioneer White House news photographer" and devotes a tribute to her.[8]

The White House Correspondents' Association, to which Carpenter belonged, has a photo of her with other members who covered President Truman. Marion Carpenter, the only woman present, is on the front row, third from the right.[16] It was not until 1962, when President John F. Kennedy objected to the ban against women members at the annual WHCA dinner, that they were allowed. Helen Thomas was the first woman WHCA member to attend.[11]

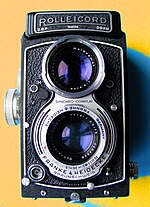

Several of Carpenter's cameras auctioned with her estate are considered historic items.[15] Her first camera was a Seneca Competitor View. It was the larger plate format, folding field camera made from 1907 to 1925.[17] Another camera was the Rolleicord III, produced in late 1949 by the Rollei-Werke Franke and Heidecke Corporation.[18] She also had the Iloca Rapid B, a German rangefinder camera from the 1950s.[19]

1946 WHNPA pictures

Ms. Carpenter's entries in the 1946 White House News Press Association contest included the following:[4]

- "White House Santa" - Showing President Harry S. Truman with gifts.

- "Favorite Dessert" - President Truman with wounded veterans during a White House garden party

- "Meat Decontrol" - President Truman telling America about the "Meat Decontrol Plan."

- "The photographers Friend" - President Truman "poses for the 'just one more.'"

- "The Last Mile" - President Truman taking a morning constitutional walk.

- "Spring at the White House" - President Truman's admiring spring magnolia blossoms.[20]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Coleman, Nick (Columnist) (November 24, 2002). "Marion Carpenter of St. Paul broke ground as a White House photographer. But she died alone and destitute". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, MN. Retrieved May 25, 2005.

- ^ Carpenter, T. L. (2010). Carpenter Families of The South. Washington, D.C.: The Author. pp. 804–805. Privately published

- ^ a b c "Marion Carpenter Award". Annual Monochrome Photojournalism Print Award. St. Paul Camera Club, St. Paul, MN. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Remembering Marion Carpenter: Pioneer White House Photographer Dies". www.whnpa.org. White House News Photographers Association] (WHNPA). November 25, 2002. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c Times Staff and Wire Reports (November 29, 2002). "Obituaries - Marion Carpenter, 82; '40s News Photographer Died in Obscurity". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ "Columnist Irks Girl 'Photog,' Gets the Soup Treatment", in The Salt Lake Tribune, March 24, 1949, p. 2.

- ^ "Marion Carpenter and her camera take time out", photo in The [Massillon, Ohio] Evening Independent, Sunday, June 23, 1947, p. 13.

- ^ a b Rush, Carol; Oukrop, Ramona; Creedon, Pamela, eds. (2003). "A Memorial Tribute to Marion Carpenter, White House News Photographer". Seeking Equity for Women in Journalism and Mass Communication Education. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 411–413. ISBN 0-8058-4574-7. The book was reprinted in May 2004 by Routledge.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Marion Carpenter, 82; Photographed Truman". The Washington Post. Washington Post Newsweek Interactive Co. November 26, 2002. Archived from the original on June 11, 2014. Article archived by HighBeam Research Archived March 31, 2002, at the Wayback Machine as of May 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c Coleman, Nick (March 8, 2003). "Last Picture: "Camera Girl" To Be Buried, Her Estate Sold". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, Minn.: Twin Cities.com. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "History of the WHCA". www.whca.net. White House Correspondents' Association. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ Google Books (1949). "A new political leader rises in the West I Marion Carpenter credits on page 37 and article photos on pages 72 and 73 are hers via Kansas City Star and page 74 are hers directly". Life, May 23, 1949. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Newsletter 1950, Saint Paul Camera Club

- ^ Commire, Anne; Klezmer, Deborah, eds. (2007). Dictionary of Women Worldwide: 25,000 Women Through The Ages. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson Gale (Waterford, Connecticut: Yorkin Publications). ISBN 978-0-7876-7585-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) See also: Carpenter, Marion (1920–2002). HighBeam Research. Accessed December 7, 2010. - ^ a b c Jack, El-Hai (September 1, 2004). "Article: Camera Obscura". Minnesota Monthly. www.minnesotamonthly.com Greenspring Media Group Inc. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012.

- ^ "Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, unidentified members of the White House press corps on the south lawn, c. 1950s" (Picture). Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Nakamura, Karen (2005). "Seneca Competitor View". www.photoethnography.com. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Nakamura, Karen (2005). "Rollei Rolleicord III". www.photoethnography.com. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Nakamura, Karen (2005). "Iloca Rapid B". www.photoethnography.com. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Althaus, Bill (1984). "Page 25 - Remembering Harry Truman". The Rotarian, November 1984. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

External links

- "Free-lance photographer Marion Carpenter demonstrates how she threw a bowl of Senate bean soup at columnist Tris Coffin in the Senate Dining room ...", Acme telephoto, WA 9 3/21 (This may be 1949 March 21).