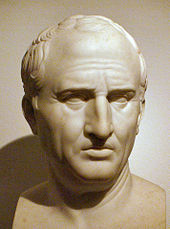

Marcus Marius Gratidianus

Marcus Marius Gratidianus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | c. 125 BC | ||||||

| Died | 82 BC Tomb of the Catuli or Lepidi | ||||||

| Office |

| ||||||

| Relatives |

| ||||||

| Military career | |||||||

| Rank | Legate | ||||||

| Wars | |||||||

Marcus Marius Gratidianus (c. 125 – 82 BC) was a Roman praetor and supporter of Gaius Marius during the civil war between the followers of Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla. As praetor, Gratidianus is known for his policy of currency reform during the economic crisis of the 80s BC.

Although this period of Roman history is marked by the extreme violence and cruelty practiced by partisans on each side, Gratidianus suffered a particularly vicious death during Sulla's proscription; in the most sensational accounts, he was tortured and dismembered by Catiline at the tomb of Quintus Lutatius Catulus, in a manner that evoked human sacrifice, and his severed head was carried through the streets of Rome on a pike.

Family and career

Gratidianus was the son of Marcus Gratidius, of the gens Gratidia from Arpinum, and Maria, the sister of Gaius Marius. After his father's death, he was adopted by his uncle, Marcus Marius, whose name he then assumed according to Roman custom, becoming Marcus Marius Gratidianus. Gratidianus' aunt married Marcus Tullius Cicero, grandfather of the celebrated orator.[3] Gratidianus was a close friend of his cousin, the young Cicero. He may also have had a particularly pungent relationship with his brother-in-law; there is reason to believe that his sister, Gratidia, was the first wife of Lucius Sergius Catilina, or "Catiline", who was later accused by Cicero of Gratidianus' torture and murder.[4]

Gratidius, his natural father, was a close friend of Marcus Antonius the orator and consul of 99 BC. He was killed circa 102 BC, while serving as a prefect under Antonius in Cilicia.[5] In 92 BC, Antonius deployed his famed oratorical skills in defending his friend's son when Gratidianus was sued by the oyster-breeder and real-estate speculator Sergius Orata in a civil case involving the sale of a property on the Lucrine Lake.[6] Orata was not without his own high-powered speaker, in the person of Lucius Licinius Crassus. Cicero says Orata was trying to force Gratidianus to buy back the property when Orata's business plan for farm-raised oysters fell through, perhaps because of unforeseen complications arising from water rights or fishing rights.[7] Sometime before 91 BC, a claim, probably also a civil suit, was filed against Gratidianus by Gaius Visellius Aculeo, supported again by Crassus. A Lucius Aelius Lamia spoke on behalf of Gratidianus, but the grounds for the suit are unknown.[8]

Gratidianus was probably tribune of the plebs in 87 BC;[9] if so, then he was among the six tribunes who left the city to take up arms when Lucius Cornelius Cinna, one of his uncle's allies, was banished.[10] He was a legate that same year, probably the commander named Marius[11] who was sent north by Cinna with the objective of seizing Ariminum and cutting off any reinforcements that might be sent to Sulla from Cisalpine Gaul. This Marius defeated Publius Servilius Vatia and took control of his army.[12]

By the end of 87, Gratidianus had returned to Rome with Cinna and Gaius Marius. He took on the prosecution of Quintus Lutatius Catulus, a move that was later to prove fateful. Catulus had been the colleague of Marius during his consulship in 102 BC, and had shared his triumph over the Cimbri, but had later broken with him. Rather than face the inevitable guilty verdict, Catulus committed suicide.[13] The charge was probably perduellio, submitted to the judgment of the people (iudicium populi), for which the punishment was death by scourging at the stake.[14]

Currency reform and cult following

As praetor in 85, Gratidianus was among those officials who attempted to address Rome's economic crisis. A number of praetors and tribunes drafted a currency reform measure to reassert the former official exchange rate of silver (the denarius) and the bronze as, which had been allowed to fluctuate and destabilize. Gratidianus seized the opportunity to attach his name to the edict and claim credit for publishing it first. The currency measure pleased the equites, or business class, more than did the debt reform legislation of Lucius Valerius Flaccus, which had permitted the repayment of loans at one-quarter of the amount owed,[15] and it was enormously popular with the plebs.

An alternative view of the reform, based mainly on a "hopelessly confused"[16] statement by Pliny, is that Gratidianus introduced a method for detecting counterfeit money. The two reforms are not incompatible,[17] but historian and numismatist Michael Crawford finds no widespread evidence of silver-plated or counterfeit denarii in surviving coin hoards from the period leading up to the edict. Since the measures taken by Gratidianus cannot be shown to address a problem of counterfeit money, the edict is best understood as part of the Cinnan government's efforts to restore and create a perception of stability in the wake of the civil war.[18]

Cicero says the people expressed their gratitude by offering wine and incense before images of Gratidianus at street-corner shrines (compita, singular compitum). Each neighborhood (vicus) had a compitum within which its guardian spirits, or Lares, were thought to reside. During the Compitalia, a new year festival, the cult images were displayed in procession. Festus and Macrobius thought that the "dolls" were ritual replacements for human sacrifices to the spirits of the dead. The sources express no surprise or disapproval toward tending cult for a living man, which may have been a tradition otherwise little evidenced; the theological basis of the homage paid to Gratidianus is unclear.[19] In historical times, the Compitalia included a purification (lustratio) and the sacrifice of a pig who was first paraded around the city. Street theater, including farces that satirized current political events, was a feature. Because it encouraged the people to assemble and possibly foment insurrection, there were sporadic efforts among the elite to regulate or suppress the Compitalia.[20]

The political aspect suggests why the display of Gratidianus' image would be viewed as dangerous in the rivalry between the populares and the optimates, the faction of Sulla. Cicero uses his cousin's subsequent fall as a cautionary tale about relying on popular support.[21] This form of devotion toward a living man has also been pointed to as a precedent for so-called "emperor worship" in the Imperial era.[22]

Seneca, following Cicero's lead, criticizes Gratidianus for compromising his integrity in claiming credit for the legislation, by which he had hoped to garner support for his candidacy as consul.[23] In the event, his party failed to support his bid, and the honor paid to him by the people probably contributed to the viciousness of the actions taken against him later by the supporters of Sulla.[24]

Twice praetor

Gratidianus had an unusual second praetorship, possibly as a "consolation prize" granted him when the Cinnans decided to back the younger Marius and Gnaeus Papirius Carbo for the consulship of 82. Although his ambitions were known and his qualifications far exceeded those of his cousin, Gratidianus probably never made a formal announcement of his candidacy for the consulship, and is assumed to have stepped aside for the sake of the Cinnans' unity. The more likely candidates from their party would have been Gratidianus and Quintus Sertorius; the political snub evidently contributed to the latter's secession in Spain. The dates for Gratidianus' praetorships are arguable; T.R.S. Broughton gives 86 and 84, but the timing of the currency reform makes 85 a more secure date, with the second term in 84, 83, or 82.[25]

Sacrificial death

During the closing violence of the civil war, Gratidianus was tortured and killed. A death, if Sulla were victorious, was likely never in doubt.[26] Details vary and proliferate in their brutality over time. Cicero and Sallust offer the earliest accounts, but the works in which these survive are fragmentary.

Cicero described his cousin's murder in a speech during his candidacy for the consulship in 64 BC, nearly two decades after the fact. He had been a young man in his twenties at the time of the killing, and possibly an eyewitness. What is known of this speech, and thus Cicero's version of the events, depends on notes provided by the first-century grammarian Asconius.[27] By chance, the surviving quotations from Cicero name neither the victim nor the executioner; these are supplied by Asconius. One of Cicero's purposes in the speech was to smear his rivals, among them Catiline, whose participation in the crime Cicero asserted repeatedly throughout.[28] The orator claimed that Catiline cut off Gratidianus' head, and carried it through the city from the Janiculum to the Temple of Apollo, where he delivered it to Sulla "full of soul and breath".[29]

A fragment from Sallust's Histories omits mention of Catiline in describing the death: Gratidianus "had his life drained out of him piece by piece, in effect: his legs and arms were first broken, and his eyes gouged out".[30] A more telling omission is that the execution of Gratidianus is not among Sallust's allegations against Catiline in his Bellum Catilinae ("The War of Catiline").[31] Sallust's description of the death, however, influenced those of Livy, Valerius Maximus, Seneca, Lucan, and Florus, with the torture and mutilation varied and amplified.[32] Although B. A. Marshall argued that the versions of Cicero and Sallust constituted two different traditions, and that only Cicero implicated Catiline,[33] other scholars have found no details in the two Late Republican accounts that are mutually exclusive or that exculpate Catiline.[34]

Later sources add the detail that Gratidianus was tortured at the tomb of the gens Lutatia, because his prosecution had prompted the suicide of Quintus Lutatius Catulus. Despite the strength and persistence of the tradition that Catiline took the lead role in the execution, the more logical instigator would have been Catulus' son, exhibiting pietas towards his father by seeking revenge as an alternative to justice.[35] But the dutiful son may not have wanted to bloody his own hands with the deed: "One would not expect the polished Catulus actually to preside over the torture, and carry the head to Sulla", observes Elizabeth Rawson, noting that Catulus was later known as the friend and protector of Catiline.[36] The site of the family tomb, otherwise unknown, is mentioned only in connection with this incident and identified vaguely as "across the Tiber",[37] which accords with Cicero's statement that the head was carried from the Janiculum to the Temple of Apollo.[38]

Sallust himself may indirectly site the killing at the tomb in a speech in which Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, the consular colleague of Catulus in 78 BC who eventually confronted him on the battlefield,[39] addressed those Romans in opposition to Sulla: "In just this way have you seen human sacrifices and tombs stained with citizens' blood".[40] Blood shed at a tomb implies that the killing amounted to a sacrifice, in appeasement for an ancestor's Manes. Human sacrifices at Rome were rare, but documented in historical times — "their savagery was closely connected with religion"[41] — and had been banned by law only fifteen years before the death of Gratidianus.[42]

In the Commentariolum

The relative "lateness" of specifying the tomb of Catulus as the site also depends on the dating of one of the other sources on the killing, the Commentariolum petitionis, an epistolary pamphlet traditionally attributed to Cicero's brother, Quintus, but suspected of being an exercise in prosopopoeia by another writer in Imperial times.[43] The epistle presents itself as having been written in 64 BC by Quintus for his brother during his candidacy for the consulship;[44] if authentically the work of Quintus, it would be contemporary with Cicero's own account of Gratidianus' death, and provide a kind of "missing link" in the narrative tradition. The Commentariolum says that Catiline

killed a man who was most beloved to the Roman people; with the Roman people looking on, he scourged M. Marius with vine-staffs[45] through the whole city, drove him to the tomb, and there mutilated him with every torture. While he was alive and in an upright position,[46] Catiline took a sword in his own right hand and severed his neck, holding on to the hair at the top of his head with his left hand. He carried the head by hand while streams of blood flowed between his fingers.[47]

The tomb is not specified as that of the Lutatii, but the Commentariolum places an emphasis on the Roman people as witness that is present also in Cicero's speech and Asconius' notes, as well as Sallust's "Speech of Lepidus".

Neronian versions

Seneca, though closely echoing Sallust's wording, names Catiline, adds to the list of mutilations the cutting out of Gratidianus' tongue, and places the killing at the tomb of Catulus, explicitly linking the favor of the people to the extreme measures taken at his death:

The people had dedicated statues to Marcus Marius throughout the neighborhoods and offered devotions with frankincense and wine; Lucius Sulla gave the order for his legs to be broken, his eyes gouged out, his tongue and his hands cut off and — as if he could die as many times as he was wounded — systematically carved up his body inch by inch. Who was the henchman on command? Who else but Catilina, even then training his hands at every misdeed? In front of the tomb of Quintus Catulus, he took hold of Marius — a man who had set a bad precedent, but a champion of the people nonetheless, loved not so much undeservedly as too well — and with great seriousness of purpose toward the ashes of a most gentle man, shed his blood drop by measured drop. Marius was worthy of the things that he suffered, Sulla was worthy of what he had ordered, and Catilina was worthy of what he did, but the republic did not deserve to take the sword-blades from both enemies and avengers into her very core.[48]

Lucan, Seneca's nephew and like him writing under the Imperial terror of Nero, who drove them both to suicide, has the most extensive list of tortures in his epic poem on the civil war of the 40s. The historicity of Lucan's epic should be treated with care; its aims are more like those of Shakespeare's history plays or the modern historical novel, in that factuality is subordinate to character and theme. Lucan places his account in the mouth of an old man who had lived through Sulla's civil war four decades before the time narrated in the poem, and like the earlier sources emphasizes that the Roman people were witnesses to the act. "We saw", the anonymous old man asserts, stepping out of the crowd to speak like the leader of a tragic chorus in cataloguing the dismemberment. The killing is presented unambiguously as a human sacrifice: "What should I report about the blood that appeased the spirits of Catulus' dead ancestors (manes... Catuli)? We watched when Marius was strung up as a victim for the dreadful underworld rites, though the shades themselves may not have wanted it, a pious deed that should not be spoken of for a tomb that could not be filled".[49] Lucan, however, diverts guilt from any individual by distributing specific mutilations among nameless multiple assailants: "This man slices off the ears, another the nostrils of the hooked nose; that man popped the eyeballs from their sockets — he dug out the eyes last, after they bore witness for the other body parts".[50]

Rawson pointed out that the piling up of atrocities in accounts of the Roman civil wars should not be discounted too quickly as literary invention: "Sceptical modern historians sometimes suffer from a happy failure of imagination in refusing to envisage the horrors which we all ought to know occur too often in civil war". Such gruesome catalogues are characteristic of Roman historians rather than their Greek models, she noted, and Sallust was the first to provide lists of concrete and "horrific exempla".[51]

Political victim

Though documented, human sacrifice was rare in Rome during the historical period. Livy and Plutarch both considered it alien to Roman tradition. This aversion is asserted also in an aetiological myth about sacrifice in which Numa, second king of Rome, negotiates with Jupiter to replace the requested human victims with vegetables. In the first century BC, human sacrifice survived perhaps only as travesty or accusation. Julius Caesar was accused — rather vaguely — of sacrificing two mutinous soldiers in the Campus Martius.[52] On the anniversary of Caesar's death in 40 BC, after achieving a victory at the siege of Perugia, the future Augustus executed 300 senators and knights who had fought against him under Lucius Antonius. Lucius was spared. Perceptions of the clemency of Augustus on this occasion vary wildly.[53] Both Suetonius[54] and Cassius Dio[55] characterize the slaughter as a sacrifice, noting that it occurred on the Ides of March at the altar to the divus Julius, the victor's newly deified adoptive father.[56] It can be difficult to discern whether such an act was intended to be a genuine sacrifice, or only to evoke a sacral aura of dread in the minds of observers and those to whom it would be reported.[57] Moreover, these two incidents took place within parameters of victory and punishment in a military setting, outside the civil and religious realm of Rome.[58]

The intentions of those who carried out these acts may be unrecoverable; surviving sources only indicate which elements were worth noting and might be construed as sacral. Orosius, whose primary source for the Republic was the lost portions of Livy's history,[59] provides the peculiar detail that Gratidianus was held in a goat-pen before he was bound and exhibited.[60] Like the sacrificial pig at the Compitalia, he was paraded through the streets, past the very shrines at which his image had received honors,[61] while he was whipped. Various forms of flogging or striking were ritual acts in Roman religion, such as the sacer Mamurio in which an old man was driven through the city while beaten with sticks in what has been interpreted as a pharmakos or scapegoat ritual;[62] beatings, such as the semi-ritualized fustuarium, were also a disciplinary and punitive measure in the military.[63] Accounts emphasize that Gratidianus was dismembered methodically, another feature of sacrifice. Finally, his severed head, described as still oozing with life, was carried to the Temple of Apollo in the Campus Martius, a site associated with the ritual of the October Horse, whose head was displayed and whose tail was also carried through the city and delivered freshly bloodied to the Regia. "The sacrality of Gratidianus' execution", it has been noted, "was a symbolic negation of his semi-divine status as popular saviour and hero".[64]

References

- ^ Broughton 1952, pp. 50, 589; Zmeskal 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Zmeskal 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Seager 1994, p. 173; Dyck 1996, p. 598.

- ^ Evidence of the marriage from a fragment from Sallust's Historiae (1.37, with the commentary on the passage by P. McGushin, Sallust: the Histories, 1992); Syme, Ronald (1964), Sallust, University of California Press, pp. 85–86, ISBN 978-0-520-92910-4: if they were married, "it can be taken that Catilina promptly discarded her". The existence of a marriage between Gratidianus' sister and Catiline is a subject of debate and often doubted.

- ^ Cicero, De legibus 36 and Brutus 168.

- ^ Cicero, De oratore 1.178 and De officiis 3.67; E. Badian, "Caepio and Norbanus: Notes on the Decade 100–90 BC", Historia 6 (1957), 332; John H. D'Arms, "The Campanian Villas of C. Marius and the Sullan Confiscation", Classical Quarterly 18 (1968), p. 185, note 6.

- ^ The legal grounds for the suit was easement (servitude), which Orata claimed (wrongly, according to Cicero) that Gratidianus had failed to disclose. For further discussion of the case, see Cynthia J. Bannon, "Servitudes for Water Use in the Roman Suburbium", Historia 50 (2001), pp. 47–50.

- ^ Cicero, De oratore 2.262, 269; Erich S. Gruen, "Political Prosecutions in the 90's BC", Historia 15 (1966), p. 52, note 121; Alexander 1990, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Unless otherwise noted, offices and dates are from T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, vol. 2, 99 BC–31 BC (New York: American Philological Association, 1952), pp. 50, 52 (note 8), 57, 59 (note 1), 60, 589. Some slight question exists as to whether Gratidianus was a tribune this year.

- ^ Seager 1994, p. 174; Dyck 1996, p. 598.

- ^ Granius Licinianus 35.20; there is some uncertainty as to which Marius this was. He was probably not the son of Gaius Marius, who seems to have been with his father at the time.

- ^ Dyck 1996, p. 598; Marshall 1985, p. 125 n. 8; Erich Gruen, Roman Politics and the Criminal Courts, 149–78 BC (Cambridge, Mass., 1968), pp. 232–234.

- ^ Alexander 1990, p. 60, citing re Gratidianus' prosecution of Catulus, Cic. De oratore 3.9, Brutus 307, Tusculanae Quaestiones 5.56, De natura deorum 3.80; Diodorus Siculus 39.4.2; Velleius Paterculus 2.22.4; Val. Max. 9.12.4; Plut. Mar. 44.5; Appian, Bellum Civile 1.74; Flor. Epit. 2.9.15; Berne Scholiast on Lucan 2.173; Bobbio Scholiast 176 (Stangl); Augustine of Hippo, De civitate Dei 3.27.

- ^ H.H. Scullard, From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68 (Routledge, 5th edition 1988), p. 73 online.

- ^ Michael H. Crawford, Coinage and Money under the Roman Republic (University of California Press, 1985), p. 191 online.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 33.46. The gratitude of the plebs is consistent even when specific accounts of Gratidianus' reforms differs; see David Bruce Hollander, Money in the Late Roman Republic (Brill, 2007), p. 29 online.

- ^ Crawford, Coinage and Money under the Roman Republic, pp. 190–192, repeating an argument he first made in "The edict of M. Marius Gratidianus", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 14 (1968) 1–4.

- ^ The cult of Gratidianus may thus be part of precedent in the connection made later between the cult of Augustus and the neighborhood altars of the Lares in 12 BC; see Stefan Weinstock, Divus Julius (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), p. 295, and further discussion under Imperial cult.

- ^ John Bert Lott, The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 14 online, 34–38 et passim. "The associated games, which as neither state-sponsored ludi nor private benefactions had an ambiguous status, were aimed solely at the urban plebs, arose out of the mood of holiday abandon, and evidently offered — or could be manipulated to provide — a release for subversive sentiment": Richard C. Beacham, Spectacle Entertainments of Early Imperial Rome (Yale University Press, 1999), pp. 55–56 online. A ban on guild associations referred to by Cicero (In Pisonem 8) was extended to suppress the Compitalia.

- ^ Cicero, De officiis 3.80.

- ^ Ittai Gradel, Emperor Worship and Roman Religion (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 51 online.

- ^ Seneca, De ira 3.18.

- ^ Seager 1994, pp. 180–181; Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 94–95 online: "Gratidianus' death seems connected to the special honors he had received during his lifetime".

- ^ C.F. Conrad, "Notes on Roman Also-Rans", in Imperium sine fine: T. Robert S. Broughton and the Roman Republic (Franz Steiner, 1996), pp. 104–105 online, citing also G. V. Sumner, The Orators in Cicero's Brutus (Toronto, 1973), pp. 118–119.

- ^ Lovano 2002, pp. 132 n. 81, 134. "Sulla had given... Mithridates, the opportunity to negotiate peace... he gave his fellow Romans and all Italians a similar chance on his return to Italy. Had his negotiations been fully successful, Sulla probably would have only eliminated the most undoubted Cinnans, such as Carbo and Gratidianus".

- ^ The relevant passages from Cicero are In Toga Candida fragments 2, 9, 10, and 16 in I. Puccioni, M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationum Deperditarum Fragmenta (Milan, 1972, 2nd edition) and in Stangl 65, 68, 69–70; Asconius, 83.26–84.1 (on fragment 2), 90.3–5 (fragment 9), 87.16–18 (fragment 10), and 89.25–27 (fragment 16) in the edition of A.C. Clark (Oxford, 1907).

- ^ Crimen saepius ei tota oratione obicit: Asconius, In orationem in toga candida 65 (Stangl). Therefore, if the speech had survived more or less intact, a clearer picture of the killing, if colored by Cicero's biases, would have emerged.

- ^ Plenum animae et spiritus: Asconius 69 (Stangl); Wiseman 1994, p. 348 n. 106 for citations of ancient sources.

- ^ Sallust, Histories 1.44M: ut in M. Mario, cui fracta prius crura brachiaque et oculu effossi, scilicet ut per singulos artus expiraret.

- ^ Jane W. Crawford, M. Tullius Cicero. The Fragmentary Speeches (American Philological Association, 1994), p. 185 online. Cicero is also inconsistent in blaming Catiline.

- ^ Livy, Periocha 88; Valerius Maximus 9.2.1; Seneca, De Ira 3.18; Lucan, Bellum Civile 2.173–193; Florus 2.9.26 (=3.21.26). Again, because only fragments from Sallust's Historiae and Cicero's speech have survived, it is impossible to know whether these authors have embellished, or only preserved details otherwise lost.

- ^ Marshall 1985, pp. 124–33.

- ^ Rawson 1987, pp. 175–177; Damon 1993, p. 282 n. 5; Dyck 1996, p. 599.

- ^ Matthew Dillon and Lynda Garland, Ancient Rome: From the Early Republic to the Assassination of Julius Caesar (Taylor & Francis, 2005), p. 523 online; Seager, Cambridge Ancient History, p. 195.

- ^ Rawson 1987, p. 177, citing Sall. Cat. 35; Oros. 6.3.1; Cic. Sull. 81.

- ^ Orosius 5.21.7.

- ^ Cicero, In Toga Candida, Asconius 69 (Stangl).

- ^ For further discussion of these adversarial colleagues, see Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (consul 78 BC).

- ^ Sallust, "Oratio Lepidi" 1.48.14 (Historiae): Simul humanas hostias vidistis et sepulcra infecta sanguine civili. Hostia means more technically "sacrificial victim"; see host.

- ^ Andrew Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 39ff online, for a fuller discussion. A ban on human sacrifice was passed during the consulship of Publius Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus in 97 BC.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 30.12.

- ^ Such a writer would have been creating a persona based on Cicero's speech In Toga Candida, and thus the Commentariolum might still preserve accurate details not found in Asconius; see Damon, "Com. Pet. 10", p. 282, note 5.

- ^ "Here it must be recognized that there was no question of Marcus needing his brother's advice on electoral campaigning", notes Andrew Lintott; for a discussion of the Commentariolum in relation to the elder Cicero's speech In Toga Candida, see Cicero as Evidence: A Historian's Companion (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 130ff. online.

- ^ Vitibus: grape vines, but here staffs made from the tree-like stalks, which were carried by centurions as a symbol of rank and sometimes used to administer corporal punishment to soldiers; see Sara Elise Phang, Roman Military Service: Ideologies of Discipline in the Late Republic and Early Principate (Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 116 online, 125 and 129: "Beating with the tough and gnarled vitis was severe enough to leave... scars and wounds".

- ^ Presumably bound to a stake, given his broken limbs; implied also by Lucan's use of the verb pendet, "hang suspended", Bellum civile 2.176. The traditional punishment for perduellio, the charge for which Gratidianus probably prosecuted the elder Catulus, was death by scourging. The convicted man was tied to a furca or palus, originally a dead tree, arbor infelix. Those bound to an arbor infelix were considered consecrated to the chthonic gods; see Anne Weis, "The Motif of the adligatus and Tree", American Journal of Archaeology 86 (1982), p. 27. Catulus had preferred suicide to this fate, the threat of which may have shaped his son's revenge. There are also a few indications that crucifixion might have been used, contrary to custom, on citizens during the civil war. See Rawson, "Sallust on the Eighties?", pp. 175–176, and discussion at Q. Valerius Soranus: Execution. The word stanti has been emended in some editions to spiranti, parallel with Cicero's phrase plenum animae et spiritus, so that the passage means Gratidianus was still "alive and breathing" when his head was lopped off; see Damon, "Com. Pet. 10", passim.

- ^ Latin: Qui hominem carissimum populo Romano, M. Marium, inspectante populo Romano uitibus per totam urbem ceciderit, ad bustum egerit, ibi omni cruciatu lacerarit, uiuo et stanti collum gladio sua dextera secuerit, cum sinistra capillum eius a vertice teneret, caput sua manu tulerit, cum inter digitos eius riui sanguinis fluerent?

- ^ Seneca, Latin text of De ira 3.18.

- ^ Lucan, Bellum civile 2.173ff: Quid sanguine manes / placatos Catuli referam? cum victima tristes / inferias Marius forsan nolentibus umbris / pendit inexpleto non fanda piacula busto, / ... vidimus.

- ^ Hic aures, alius spiramina naris aduncae / amputat; ille cavis evolvit sedibus orbes, / ultimaque effodit spectatis lumina membris; see Elaine Fantham, Lucan. Be Bello Civili. Book II (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 112 online.

- ^ Rawson, "Sallust on the Eighties?", p. 180, noting that the cataloguing of atrocities committed against individuals is not characteristic of the historical methods of Thucydides and his tradition.

- ^ Cassius Dio 43.24 is the unique source for the incident.

- ^ Compare, for instance, the careful mitigation of Melissa Barden Dowling, Clemency and Cruelty in the Roman World (University of Michigan Press, 2006), pp. 50–51 online, to the harder-eyed view of Arthur Keaveney, The Army in the Roman Revolution (Routledge, 2007), p. 15 online.

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Augustus 15, attributing multiple but unnamed sources: "Certain sources write that three hundred men of both orders were chosen from those who surrendered, and slaughtered in the manner of sacrificial victims (more hostiarum) at the altar built for the Divine Julius on the Ides of March".

- ^ Cassius Dio 48.14.2.: "And the story goes that they did not merely suffer death in an ordinary form, but were led to the altar consecrated to the former Caesar and were there sacrificed".

- ^ The ancient sources can be oblique; for instance, Seneca, De clementia 1.11.2, refers to "Perugian altars" in listing evidence for the harshness of Augustus in youth, tempered by age, without explanation. In Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome (Routledge, 1998, 2001), Donald G. Kyle reviews this and related incidents and points out that 300 is a "conventional number" (p. 58 online).

- ^ Overview of human sacrifice in Rome by J.S. Reid, "Human Sacrifices at Rome and Other Notes on Roman Religion", Journal of Roman Studies 2 (1912) 34–52, still cited frequently on the subject.

- ^ William Warde Fowler, The Religious Experience of the Roman People from the Earliest Times to the Age of Augustus (London, 1922), p. 44 online.

- ^ David Rohrbacher, The Historians of Late Antiquity (Routledge, 2002), p. 138 Orosius online.

- ^ Orosius 5.21.7 (Latin text): "Marcus Marius was dragged from a goat-pen and bound on orders of Sulla; after he was led across the Tiber to the tomb of the Lutatii, his eyes were gouged out, his body parts were cut off bit by bit or even broken, and he was slaughtered". Livy's account survives only in Periocha 88: "Sulla polluted (inquinavit) a most glorious victory by cruelty such as no man had ever shown before. He slaughtered 8,000 men, who had surrendered, in the Villa Publica; ...and had Marius, a man of senatorial rank, killed after having his legs and arms broken, his ears cut off and his eyes gouged out".

- ^ Cicero says, possibly but not necessarily with exaggeration, that Gratidianus' statues were in every neighborhood (De officiis 3.80); Gradel, Emperor worship and Roman religion, p. 125 online.

- ^ William Warde Fowler, The Festivals of the Roman Republic: An Introduction to the Study of the Religion of the Romans (London, 1908), pp. 44–50, full text downloadable.

- ^ Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome p. 42.

- ^ A.G. Thein, Sulla's Public Image and the Politics of Civic Renewal (University of Pennsylvania, 2002), p. 127, as quoted by Flower, The Art of Forgetting, p. 306.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Michael (1990). Trials in the late Roman republic, 149 BC to 50 BC. Phoenix. Vol. 26. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5787-X.

- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Crook, John; et al., eds. (1994). The last age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 BC. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85073-8. OCLC 121060.

- Seager, Robin. "Sulla". In CAH2 9 (1994), pp. 165–207.

- Wiseman, T P. "Caesar, Pompey, and Rome, 59–50 BC". In CAH2 9 (1994), pp. 368–423.

- Damon, Cynthia (1993). "Comm. Pet. 10". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 95: 281–288. doi:10.2307/311387. ISSN 0073-0688. JSTOR 311387.

- Dyck, Andrew Roy (1996). A Commentary on Cicero, De Officiis. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10719-3.

- Keaveney, Arthur (2005) [First ed. 1982]. Sulla: the last republican (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33660-0.

- Lovano, Michael (2002). The age of Cinna: crucible of late republican Rome. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07948-8.

- Marshall, Bruce (1985). "Catilina and the execution of M. Marius Gratidianus". Classical Quarterly. 35 (1): 124–133. doi:10.1017/S0009838800014610. ISSN 0009-8388. JSTOR 638809.

- Rawson, Elizabeth (1987). "Sallust on the eighties?". Classical Quarterly. 37 (1): 163–180. doi:10.1017/S0009838800031748. ISSN 0009-8388. JSTOR 639353.

- Spina, Luigi. Ricordo "elettorale" di un assassinio (Q. Cic., Comm. pet. 10) in Classicità, Medioevo e Umanesimo (Studi in onore di S. Monti), ed. by G. Germano, Napoli 1996, pp. 57–62.

- Zmeskal, Klaus (2009). Adfinitas (in German). Vol. 1. Passau: Verlag Karl Stutz. ISBN 978-3-88849-304-1.