Caracalla

| Caracalla | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bust of Caracalla, Museo Nazionale Romano, 212–215 AD | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 28 January 198 – 8 April 217 (senior from 4 February 211) | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Septimius Severus | ||||||||

| Successor | Macrinus | ||||||||

| Co-rulers |

| ||||||||

| Born | Lucius Septimius Bassianus 4 April 188 Lugdunum | ||||||||

| Died | 8 April 217 (aged 29) On the road between Edessa and Carrhae | ||||||||

| Spouse | Fulvia Plautilla | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Severan | ||||||||

| Father | Septimius Severus | ||||||||

| Mother | Julia Domna | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Severan dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

193–211 |

||

with Caracalla 198–211 |

||

with Geta 209–211 |

||

211–217 |

||

211 |

||

Macrinus' usurpation 217–218 |

||

with Diadumenian 218 |

||

218–222 |

||

222–235 |

||

| Dynasty | ||

| Severan dynasty family tree | ||

|

All biographies |

||

| Succession | ||

|

||

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (/ˌkærəˈkælə/),[3] was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor Septimius Severus and Empress Julia Domna. Severus proclaimed Caracalla co-ruler in 198, doing the same with his other son Geta in 209. The two brothers briefly shared power after their father's death in 211, but Caracalla soon had Geta murdered by the Praetorian Guard and became sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Julia Domna had a significant share in governance, since Caracalla found administration to be mundane. His reign featured domestic instability and external invasions by the Germanic peoples.

Caracalla issued the Antonine Constitution (Latin: Constitutio Antoniniana), also known as the Edict of Caracalla, which granted Roman citizenship to all free men throughout the Roman Empire. The edict gave all the enfranchised men Caracalla's adopted praenomen and nomen: "Marcus Aurelius". Other landmarks of his reign were the construction of the Baths of Caracalla, the second-largest bathing complex in the history of Rome, the introduction of a new Roman currency named the antoninianus, a sort of double denarius, and the massacres he ordered, both in Rome and elsewhere in the empire. In 216, Caracalla began a campaign against the Parthian Empire. He did not see this campaign through to completion due to his assassination by a disaffected soldier in 217. Macrinus succeeded him as emperor three days later.

The ancient sources portray Caracalla as a cruel tyrant; his contemporaries Cassius Dio (c. 155 – c. 235) and Herodian (c. 170 – c. 240) present him as a soldier first and an emperor second. In the 12th century, Geoffrey of Monmouth started the legend of Caracalla's role as king of Britain. Later, in the 18th century, the works of French painters revived images of Caracalla due to apparent parallels between Caracalla's tyranny and that ascribed to king Louis XVI (r. 1774–1792). Modern works continue to portray Caracalla as an evil ruler, painting him as one of the most tyrannical of all Roman emperors.

Names

Caracalla's name at birth was Lucius Septimius Bassianus. He was renamed Marcus Aurelius Antoninus at the age of seven as part of his father's attempt at union with the families of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius.[4][5][1] According to the 4th-century historian Aurelius Victor in his Epitome de Caesaribus, he became known by the agnomen "Caracalla" after a Gallic hooded tunic that he habitually wore and made fashionable.[6] He may have begun wearing it during his campaigns on the Rhine and Danube.[7] Cassius Dio, who was still writing his Historia romana during Caracalla's reign,[8] generally referred to him as "Tarautas", after a famously diminutive and violent gladiator of the time, though he also calls him "Caracallus" on various occasions.[9]

Early life

Caracalla was born in Lugdunum, Gaul (now Lyon, France), on 4 April 188 to Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) and Julia Domna, thus giving him Punic paternal ancestry and Arab maternal ancestry.[10] He had a slightly younger brother, Geta, with whom Caracalla briefly ruled as co-emperor.[4][11] Caracalla was five years old when his father was acclaimed Augustus on 9 April 193.[12]

Caesar

In early 195, Caracalla's father Septimius Severus had himself adopted posthumously by the deified emperor (divus) Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180); accordingly, in 195 or 196 Caracalla was given the imperial rank of Caesar, adopting the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Caesar, and was named imperator destinatus (or designatus) in 197, possibly on his birthday, 4 April, and certainly before 7 May.[12] He thus technically became a part of the well-remembered Antonine dynasty.[13]

Co-augustus

Caracalla's father appointed Caracalla, aged 9, joint Augustus and full emperor from 28 January 198.[14][2] This was the day Septimius Severus's triumph was celebrated, in honour of his victory over the Parthian Empire in the Roman–Persian Wars; he had successfully sacked the Parthian capital, Ctesiphon, after winning the Battle of Ctesiphon, probably in October 197.[15] He was also awarded tribunician power and the title of imperator.[12] In inscriptions, Caracalla is given from 198 the title of the chief priesthood, pontifex maximus.[13][12] His brother Geta was proclaimed nobilissimus caesar on the same day, and their father Septimius Severus was awarded the victory name Parthicus Maximus.[12]

In 199, he was inducted into the Arval Brethren.[13] By the end of 199, at age 11, he was entitled pater patriae.[13] In 202, he was Roman consul, having been named consul designatus the previous year.[13] His colleague was his father, serving his own third consulship.[15]

In 202, Caracalla was forced to marry the daughter of Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, Fulvia Plautilla, whom he hated, though for what reason is unknown.[16] The wedding took place between the 9 and the 15 April, just after he turned 14.[13]

In 205, Caracalla was consul for the second time, in company with Geta – his brother's first consulship.[13] By 205, aged 16, Caracalla had got Plautianus executed for treason, though he had probably fabricated the evidence of the plot.[16] It was then that he banished his wife, whose later killing might have been carried out under Caracalla's orders.[4][16]

On 28 January 207, at age 18, Caracalla celebrated his decennalia, the tenth anniversary of the beginning of his reign.[13] The year 208 was the year of his third and Geta's second consulship.[13] Geta was himself granted the rank of Augustus and tribunician powers in September or October 209.[13][17][12]

During the reign of his father, Caracalla's mother Julia Domna had played a prominent public role, receiving titles of honour such as "Mother of the camp", but she also played a role behind the scenes helping her husband administer the empire.[18] Described as ambitious,[19] Julia Domna surrounded herself with thinkers and writers from all over the empire.[20] While Caracalla was mustering and training troops for his planned Persian invasion, Julia remained in Rome, administering the empire. Julia's growing influence in state affairs was the beginning of a trend of emperors' mothers having influence, which continued throughout the Severan dynasty.[21]

Reign as senior emperor

Geta as co-augustus

On 4 February 211, Septimius Severus died at Eboracum (present-day York, England) while on campaign in Caledonia, to the north of Roman Britain.[22]

This left his two sons and co-augusti, Caracalla and his brother, Geta, as joint inheritors of their father's throne and empire.[17][22] Caracalla adopted his father's cognomen, Severus, and assumed the chief priesthood as pontifex maximus.[23] His name became Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Pius Augustus.[23]

Caracalla and Geta ended the Roman invasion of Caledonia after concluding a peace with the Caledonians that returned the border of Roman Britain to the line demarcated by Hadrian's Wall.[17][24] During the journey back from Britain to Rome with their father's ashes, Caracalla and his brother continuously argued with one another, making relations between them increasingly hostile.[17][24] Caracalla and Geta considered dividing the empire in half along the Bosphorus to make their co-rule less hostile. Caracalla was to rule in the west and Geta was to rule in the east. They were persuaded not to do this by their mother.[24]

Geta's murder

On 26 December 211, at a reconciliation meeting arranged by their mother, Geta was assassinated by members of the Praetorian Guard loyal to the 23-year-old Caracalla. Geta died in his mother's arms. It is widely accepted, and clearly most likely, that Caracalla ordered the assassination himself, as the two had never been on favourable terms with one another, much less after succeeding their father.[22]

Caracalla then persecuted and executed most of Geta's supporters and ordered a damnatio memoriae pronounced by the Senate against his brother's memory.[6][25] Geta's image was removed from all paintings, coins were melted down, statues were destroyed, his name was struck from papyrus records, and it became a capital offence to speak or write Geta's name.[26] In the aftermath of the damnatio memoriae, an estimated 20,000 people were massacred.[25][26] Those killed were Geta's inner circle of guards and advisers, friends, and other military staff under his employ.[25]

Reign as sole emperor

When Geta died in 211, Julia Domna's responsibilities increased, because Caracalla found administrative tasks to be mundane.[18] She may have taken on one of the more important civil functions of the emperor; receiving petitions and answering correspondence.[27] The extent of her role in this position, however, is probably overstated. She may have represented her son and played a role in meetings and answering queries; however, the final authority on legal matters was Caracalla.[27] The emperor filled all of the roles in the legal system as judge, legislator, and administrator.[27]

Constitutio Antoniniana

The Constitutio Antoniniana (lit. "Constitution of Antoninus", also called "Edict of Caracalla" or "Antonine Constitution") was an edict issued in 212 by Caracalla declaring that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship,[28] with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves.[29][30][31][32][33]

Before 212, the majority of Roman citizens had been inhabitants of Roman Italia, with about 4–7% of all peoples in the Roman Empire being Roman citizens at the time of the death of Augustus in AD 14. Outside Rome, citizenship was restricted to Roman coloniae[a] – Romans, or their descendants, living in the provinces, the inhabitants of various cities throughout the Empire – and small numbers of local nobles such as kings of client countries. Provincials, on the other hand, were usually non-citizens, although some magistrates and their families and relatives held the Latin Right.[b][37]

Dio maintains that one purpose for Caracalla issuing the edict was the desire to increase state revenue; at the time, Rome was in a difficult financial situation and needed to pay for the new pay raises and benefits that were being conferred on the military.[38] The edict widened the obligation for public service and gave increased revenue through the inheritance and emancipation taxes that only had to be paid by Roman citizens.[39] However, few of those that gained citizenship were wealthy, and while it is true that Rome was in a difficult financial situation, it is thought that this could not have been the sole purpose of the edict.[38] The provincials also benefited from this edict because they were now able to think of themselves as equal partners to the Romans in the empire.[39]

Another purpose for issuing the edict, as described within the papyrus upon which part of the edict was inscribed, was to appease the gods who had delivered Caracalla from conspiracy.[40] The conspiracy in question was in response to Caracalla's murder of Geta and the subsequent slaughter of his followers; fratricide would only have been condoned if his brother had been a tyrant.[41] The damnatio memoriae against Geta and the large payments Caracalla had made to his own supporters were designed to protect himself from possible repercussions. After this had succeeded, Caracalla felt the need to repay the gods of Rome by returning the favour to the people of Rome through a similarly grand gesture. This was done through the granting of citizenship.[41][42]

Another purpose for issuing the edict might have been related to the fact that the periphery of the empire was now becoming central to its existence, and the granting of citizenship may have been simply a logical outcome of Rome's continued expansion of citizenship rights.[42][43]

Alamannic war

In 213, about a year after Geta's death, Caracalla left Rome, never to return.[39] He went north to the German frontier to deal with the Alamanni, a confederation of Germanic tribes who had broken through the limes in Raetia.[39][44] During the campaign of 213–214, Caracalla successfully defeated some of the Germanic tribes while settling other difficulties through diplomacy, though precisely with whom these treaties were made remains unknown.[44][45] While there, Caracalla strengthened the frontier fortifications of Raetia and Germania Superior, collectively known as the Agri Decumates, so that it was able to withstand any further barbarian invasions for another twenty years.

Provincial tour

In spring 214, Caracalla departed for the eastern provinces, travelling through the Danubian provinces and the Anatolian provinces of Asia and Bithynia.[13] He spent the winter of 214/215 in Nicomedia. By 4 April 215 he had left Nicomedia, and in the summer he was in Antioch on the Orontes.[13] By December 215 he was in Alexandria in the Nile Delta, where he stayed until March or April 216.[13]

When the inhabitants of Alexandria heard of Caracalla's claims that he had killed his brother Geta in self-defence, they produced a satire mocking this as well as Caracalla's other pretensions.[46][47] Caracalla responded to this insult by slaughtering the unsuspecting deputation of leading citizens that had assembled before the city to greet his arrival in December 215, before setting his troops against Alexandria for several days of looting and plunder.[39][48]

In spring 216 he returned to Antioch and before 27 May had set out to lead his Roman army against the Parthians.[13] During the winter of 215/216 he was in Edessa.[13] Caracalla then moved east into Armenia. By 216 he had pushed through Armenia and south into Parthia.[49]

Baths

Construction on the Baths of Caracalla in Rome began in 211 at the start of Caracalla's rule. The thermae are named for Caracalla, though it is most probable that his father was responsible for their planning. In 216, a partial inauguration of the baths took place, but the outer perimeter of the baths was not completed until the reign of Severus Alexander.[50]

These large baths were typical of the Roman practice of building complexes for social and state activities in large densely populated cities.[50] The baths covered around 50 acres (or 202,000 square metres) of land and could accommodate around 1,600 bathers at any one time.[50] They were the second largest public baths built in ancient Rome and were complete with swimming pools, exercise yards, a stadium, steam rooms, libraries, meeting rooms, fountains, and other amenities, all of which were enclosed within formal gardens.[50][51] The interior spaces were decorated with colourful marble floors, columns, mosaics, and colossal statuary.[52]

Caracalla and Serapis

At the outset of his reign, Caracalla declared imperial support for the Graeco-Egyptian god of healing Serapis. The Iseum and Serapeum in Alexandria were apparently renovated during Caracalla's co-rule with his father Septimius Severus. The evidence for this exists in two inscriptions found near the temple that appear to bear their names. Additional archaeological evidence exists for this in the form of two papyri that have been dated to the Severan period and also two statues associated with the temple that have been dated to around 200 AD. Upon Caracalla's ascension to being sole ruler in 212, the imperial mint began striking coins bearing Serapis' image. This was a reflection of the god's central role during Caracalla's reign. After Geta's death, the weapon that had killed him was dedicated to Serapis by Caracalla. This was most likely done to cast Serapis into the role of Caracalla's protector from treachery.[53]

Caracalla also erected a temple on the Quirinal Hill in 212, which he dedicated to Serapis.[48] A fragmented inscription found in the church of Sant' Agata dei Goti in Rome records the construction, or possibly restoration, of a temple dedicated to the god Serapis. The inscription bears the name "Marcus Aurelius Antoninus", a reference to either Caracalla or Elagabalus, but more likely to Caracalla due to his known strong association with the god. Two other inscriptions dedicated to Serapis, as well as a granite crocodile similar to one discovered at the Iseum et Serapeum, were also found in the area around the Quirinal Hill.[54]

Monetary policy

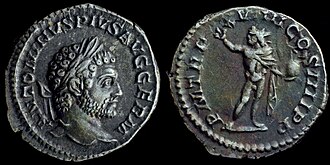

| |

| O: laureate head of Caracalla | R: Sol holding globe, rising hand

Pontifex Maximus, TRibunus Plebis XVIIII, COnSul IIII, Pater Patriae |

| silver denarius struck in Rome 216 AD; ref.: RIC 281b, C 359 | |

The expenditures that Caracalla made with the large bonuses he gave to soldiers prompted him to debase the coinage soon after his ascension.[6] At the end of Severus' reign and early into Caracalla's, the Roman denarius had an approximate silver purity of around 55%, but by the end of Caracalla's reign the purity had been reduced to about 51%.[55][56]

In 215 Caracalla introduced the antoninianus, a coin intended to serve as a double denarius.[57] This new currency, however, had a silver purity of about 52% for the period between 215 and 217 and an actual size ratio of 1 antoninianus to 1.5 denarii. This in effect made the antoninianus equal to about 1.5 denarii.[58][59][60] The reduced silver purity of the coins caused people to hoard the old coins that had higher silver content, aggravating the inflation problem caused by the earlier devaluation of the denarii.[57][58]

Military policy

During his reign as emperor, Caracalla raised the annual pay of an average legionary from 2000 sesterces (500 denarii) to 2700–3000 sesterces (675–750 denarii). He lavished many benefits on the army, which he both feared and admired, in accordance with the advice given by his father on his deathbed always to heed the welfare of the soldiers and ignore everyone else.[17][44] Caracalla needed to gain and keep the trust of the military, and he did so with generous pay raises and popular gestures.[61] He spent much of his time with the soldiers, so much so that he began to imitate their dress and adopt their manners.[6][62][63]

After Caracalla concluded his campaign against the Alamanni, it became evident that he was inordinately preoccupied with emulating Alexander the Great.[64][65] He began openly mimicking Alexander in his personal style. In planning his invasion of the Parthian Empire, Caracalla decided to arrange 16,000 of his men in Macedonian-style phalanxes, despite the Roman army having made the phalanx an obsolete tactical formation.[64][65][66] The historian Christopher Matthew mentions that the term Phalangarii has two possible meanings, both with military connotations. The first refers merely to the Roman battle line and does not specifically mean that the men were armed with pikes, and the second bears similarity to the 'Marian Mules' of the late Roman Republic who carried their equipment suspended from a long pole, which were in use until at least the 2nd century AD.[66] As a consequence, the phalangarii of Legio II Parthica may not have been pikemen, but rather standard battle line troops or possibly triarii.[66]

Caracalla's mania for Alexander went so far that he visited Alexandria while preparing for his Persian invasion and persecuted philosophers of the Aristotelian school based on a legend that Aristotle had poisoned Alexander. This was a sign of Caracalla's increasingly erratic behaviour.[65]

Parthian war

In 216, Caracalla pursued a series of aggressive campaigns in the east against the Parthians, intended to bring more territory under direct Roman control. He offered the king of Parthia, Artabanus IV of Parthia, a marriage proposal between himself and the king's daughter.[7][67] Artabanus refused the offer, realizing that the proposal was merely an attempt to unite the kingdom of Parthia under the control of Rome.[67] In response, Caracalla used the opportunity to start a campaign against the Parthians. That summer Caracalla began to attack the countryside east of the Tigris in the Parthian war of Caracalla.[67] In the following winter, Caracalla retired to Edessa, modern Şanlıurfa in south-east Turkey, and began making preparations to renew the campaign by spring.[67]

Death

At the beginning of 217, Caracalla was still based at Edessa before renewing hostilities against Parthia.[7] On 8 April 217 Caracalla, who had just turned 29, was travelling to visit a temple of the moon god Sin,[68] while on the road from Edessa to Carrhae, now Harran in southern Turkey, where in 53 BC the Romans had suffered a defeat at the hands of the Parthians.[7] After stopping briefly to urinate, Caracalla was approached by a soldier, Justin Martialis, and stabbed.[7] A Scythian bodyguard of Caracalla killed Martialis with his lance. The two Praetorian tribunes rushed to the emperor, as if to help him, and completed the assassination.[69]

Martialis had been incensed by Caracalla's refusal to grant him the position of centurion, and the praetorian prefect Macrinus, Caracalla's successor, saw the opportunity to use Martialis to end Caracalla's reign.[67] In the immediate aftermath of Caracalla's death, his murderer, Martialis, was killed as well.[7] When Caracalla was murdered, Julia Domna was in Antioch sorting out correspondence, removing unimportant messages from the bunch so that when Caracalla returned, he would not be overburdened with duties.[18] Three days later, Macrinus declared himself emperor with the support of the Roman army.[70][71]

Portraiture

Caracalla's official portrayal as sole emperor marks a break from the detached images of the philosopher-emperors who preceded him: his close-cropped haircut is that of a soldier, his pugnacious scowl a realistic and threatening presence. This rugged soldier-emperor, an iconic archetype, was adopted by most of the following emperors, such as Maximinus Thrax, who were dependent on the support of the troops to rule the empire.[72][73]

Herodian describes Caracalla as having preferred northern European clothing, Caracalla being the name of the short Gaulish cloak that he made fashionable, and he often wore a blond wig.[74] Dio mentions that when Caracalla was a boy, he had a tendency to show an angry or even savage facial expression.[75]

The way Caracalla wanted to be portrayed to his people can be seen through the many surviving busts and coins. Images of the young Caracalla cannot be clearly distinguished from his younger brother Geta.[76] On the coins, Caracalla was shown laureate after becoming augustus in 197; Geta is bareheaded until he became augustus himself in 209.[77] Between 209 and their father's death in February 211, both brothers are shown as mature young men who were ready to take over the empire.

Between the death of the father and the assassination of Geta towards the end of 211, Caracalla's portrait remains static with a short full beard while Geta develops a long beard with hair strains like his father. The latter was a strong indicator of Geta's effort to be seen as the true successor to their father, an effort that came to naught when he was murdered.[77] Caracalla's presentation on coins during the period of his co-reign with his father, from 198 to 210, are in broad terms in line with the third-century imperial representation; most coin types communicate military and religious messages, with other coins giving messages of saeculum aureum and virtues.[78]

During Caracalla's sole reign, from 212 to 217, a significant shift in representation took place. The majority of coins produced during this period made associations with divinity or had religious messages; others had non-specific and unique messages that were only circulated during Caracalla's sole rule.[79]

Legacy

Damnatio memoriae

Caracalla was not subject to a proper damnatio memoriae after his assassination; while the Senate disliked him, his popularity with the military prevented Macrinus and the Senate from openly declaring him to be a hostis. Macrinus, in an effort to placate the Senate, instead ordered the secret removal of statues of Caracalla from public view. After his death, the public made comparisons between him and other condemned emperors and called for the horse race celebrating his birthday to be abolished and for gold and silver statues dedicated to him to be melted down. These events were, however, limited in scope; most erasures of his name from inscriptions were either accidental or occurred as a result of re-use. Macrinus had Caracalla deified and commemorated on coins as Divus Antoninus. There does not appear to have been any intentional mutilation of Caracalla in any images that were created during his reign as sole emperor.[80]

Classical portrayal

Caracalla is presented in the ancient sources of Cassius Dio, Herodian, and the Historia Augusta as a cruel tyrant and savage ruler.[81] This portrayal of Caracalla is only further supported by the murder of his brother Geta and the subsequent massacre of Geta's supporters that Caracalla ordered.[81] Alongside this, these contemporary sources present Caracalla as a "soldier-emperor" for his preference of the soldiery over the senators, a depiction that made him even less popular with the senatorial biographers.[81] Dio explicitly presented Caracalla as an emperor who marched with the soldiers and behaved like a soldier. Dio also often referred to Caracalla's large military expenditures and the subsequent financial problems this caused.[81] These traits dominate Caracalla's image in the surviving classical literature.[82] The Baths of Caracalla are presented in classical literature as unprecedented in scale, and impossible to build if not for the use of reinforced concrete.[83] The Edict of Caracalla, issued in 212, however, goes almost unnoticed in classical records.[82]

The Historia Augusta is considered by historians as the least trustworthy for all accounts of events, historiography, and biographies among the ancient works and is full of fabricated materials and sources.[84][85][86][87][88] The works of Herodian of Antioch are, by comparison, "far less fantastic" than the stories presented by the Historia Augusta.[84] Historian Andrew G. Scott suggests that Dio's work is frequently considered the best source for this period.[89] However, historian Clare Rowan questions Dio's accuracy on the topic of Caracalla, referring to the work as having presented a hostile attitude towards Caracalla and thus needing to be treated with caution.[90] An example of this hostility is found in one section where Dio notes that Caracalla is descended from three different races and that he managed to combine all of their faults into one person: the fickleness, cowardice, and recklessness of the Gauls, the cruelty and harshness of the Africans, and the craftiness that is associated with the Syrians.[90] Despite this, the outline of events as presented by Dio are described by Rowan as generally accurate, while the motivations that Dio suggests are of questionable origin.[90] An example of this is his presentation of the Edict of Caracalla; the motive that Dio appends to this event is Caracalla's desire to increase tax revenue. Olivier Hekster, Nicholas Zair, and Rowan challenge this presentation because the majority of people who were enfranchised by the edict would have been poor.[38][90] In her work, Rowan also describes Herodian's depiction of Caracalla: more akin to a soldier than an emperor.[91]

Medieval legends

Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudohistorical History of the Kings of Britain makes Caracalla a king of Britain, referring to him by his actual name "Bassianus", rather than by the nickname Caracalla. In the story, after Severus' death the Romans wanted to make Geta king of Britain, but the Britons preferred Bassianus because he had a British mother. The two brothers fought until Geta was killed and Bassianus succeeded to the throne, after which he ruled until he was overthrown and killed by Carausius. However, Carausius' revolt actually happened about seventy years after Caracalla's death in 217.[92]

Eighteenth-century artworks and the French Revolution

Caracalla's memory was revived in the art of late eighteenth-century French painters. His tyrannical career became the subject of the work of several French painters such as Greuze, Julien de Parme, David, Bonvoisin, J.-A.-C. Pajou, and Lethière. Their fascination with Caracalla was a reflection of the growing discontent of the French people with the monarchy. Caracalla's visibility was influenced by the existence of several literary sources in French that included both translations of ancient works and contemporary works of the time. Caracalla's likeness was readily available to the painters due to the distinct style of his portraiture and his unusual soldier-like choice of fashion that distinguished him from other emperors. The artworks may have served as a warning that absolute monarchy could become the horror of tyranny and that disaster could come about if the regime failed to reform. Art historian Susan Wood suggests that this reform was for the absolute monarchy to become a constitutional monarchy, as per the original goal of revolution, rather than the republic that it eventually became. Wood also notes the similarity between Caracalla and his crimes leading to his assassination and the eventual uprising against, and death of, King Louis XVI: both rulers had died as a result of their apparent tyranny.[93]

Modern portrayal

Caracalla has had a reputation as being among the worst of Roman emperors, a perception that survives even into modern works.[94] The art and linguistics historian John Agnew and the writer Walter Bidwell describe Caracalla as having an evil spirit, referring to the devastation he wrought in Alexandria.[95] The Roman historian David Magie describes Caracalla, in the book Roman Rule in Asia Minor, as brutal and tyrannical and points towards psychopathy as an explanation for his behaviour.[96][97] The historian Clifford Ando supports this description, suggesting that Caracalla's rule as sole emperor is notable "almost exclusively" for his crimes of theft, massacre, and mismanagement.[98]

18th-century historian Edward Gibbon, author of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, takes Caracalla's reputation, which he had received for the murder of Geta and subsequent massacre of Geta's supporters, and applied it to Caracalla's provincial tours, suggesting that "every province was by turn the scene of his rapine and cruelty".[94] Gibbon compared Caracalla to emperors such as Hadrian who spent their careers campaigning in the provinces and then to tyrants such as Nero and Domitian whose entire reigns were confined to Rome and whose actions only impacted upon the senatorial and equestrian classes residing there. Gibbon then concluded that Caracalla was "the common enemy of mankind", as both Romans and provincials alike were subject to "his rapine and cruelty".[39]

This representation is questioned by the historian Shamus Sillar, who cites the construction of roads and reinforcement of fortifications in the western provinces, among other things, as being contradictory to the representation made by Gibbon of cruelty and destruction.[99] The history professors Molefi Asante and Shaza Ismail note that Caracalla is known for the disgraceful nature of his rule, stating that "he rode the horse of power until it nearly died of exhaustion" and that though his rule was short, his life, personality, and acts made him a notable, though likely not beneficial, figure in the Roman Empire.[100]

Severan dynasty family tree

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

Bibliography:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ^ Coloniae were cities of Roman citizens founded in conquered provinces.[34]

- ^ The Latin Rights or ius Latii were an intermediate or probationary stage for non-Romans obtaining full Roman citizenship. Aside from the right to vote, and ability to pursue a political office, the Latin Rights were just a limited Roman citizenship.[35][36]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Hammond 1957, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Cooley 2012, p. 495.

- ^ "Caracalla". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Gagarin, Michael (2009). Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 51.

- ^ Tabbernee, William; Lampe, Peter (2008). Pepouza and Tymion: The Discovery and Archaeological Exploration of a Lost Ancient City and an Imperial Estate. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020859-7.

- ^ a b c d Dunstan 2011, pp. 405–406.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 74. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ Swan, Michael Peter (2004). The Augustan Succession: An Historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3, 30. ISBN 0-19-516774-0.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Book 79

- ^ Shahid, Irfan (1984). Rome and the Arabs. Georgetown, Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. p. 33. ISBN 0-88402-115-7.

- ^ Dunstan 2011, p. 399.

- ^ a b c d e f Cooley 2012, pp. 495–496

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Caracalla". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 156–161. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: the Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press. p. 19.

- ^ a b Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Septimius Severus". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 149–155. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ a b c Dunstan 2011, p. 402.

- ^ a b c d e Dunstan 2011, p. 405.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 76. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ Dunstan 2011, p. 299.

- ^ Dunstan 2011, p. 404.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: the Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press. p. 46.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ a b Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Caracalla". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 156–161. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 70. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ a b c Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ a b Varner, Eric, R. (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. p. 168. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Tuori, Kaius (2016). "Judge Julia Domna? A Historical Mystery and the Emergence of Imperial Legal Administration". The Journal of Legal History. 37 (2): 180–197. doi:10.1080/01440365.2016.1191590. ISSN 0144-0365. S2CID 147778542.

- ^ Lim, Richard (2010). The Edinburgh Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome: Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 114.

- ^ Hekster & Zair 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Levine, Lee (1975). Caesarea Under Roman Rule. Brill Archive. p. 195. ISBN 90-04-04013-7.

- ^ Benario, Herbert (1954). "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 85: 188–196. doi:10.2307/283475. JSTOR 283475.

- ^ Cairns, John (2007). Beyond Dogmatics: Law and Society in the Roman World: Law and Society in the Roman World. Edinburgh University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7486-3177-3.

- ^ Giessen Papyrus, 40,7-9 "I grant to all the inhabitants of the Empire the Roman citizenship and no one remains outside a civitas, with the exception of the dediticii"

- ^ Whittock, Martyn John; Whittock, Martyn (1991). The Roman Empire. Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 0-435-31274-X.

- ^ Johnson, Allan; Coleman-Norton, Paul; Bourne, Frank; Pharr, Clyde (1961). Ancient Roman Statutes: A Translation with Introduction, Commentary, Glossary, and Index. The Lawbook Exchange. p. 266. ISBN 1-58477-291-3.

- ^ Zoch, Paul (2000). Ancient Rome: An Introductory History. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-8061-3287-6.

- ^ Lavan, Myles (2016). "The Spread of Roman Citizenship, 14–212 CE: Quantification in the face of high uncertainty" (PDF). Past and Present (230): 3–46. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtv043. hdl:10023/12646.

- ^ a b c Hekster & Zair 2008, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c d e f Dunstan 2011, p. 406.

- ^ Hekster & Zair 2008, p. 48.

- ^ a b Hekster & Zair 2008, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Rowan 2012, p. 127.

- ^ Hekster & Zair 2008, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). The Romans, from village to empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 413. ISBN 0-19-511875-8.

- ^ Scott 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Morgan, Robert (2016). History of the Coptic Orthodox People and the Church of Egypt. FriesenPress. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4602-8027-0.

- ^ Fisher, Warren (2010). The Illustrated History of the Roman Empire: From Caesar's Crossing the Rubicon (49 BC) to the Empire's Fall, 476 AD. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4490-7739-6.

- ^ a b Melton, Gordon, J. (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5000 Years of Religious History. p. 338.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). The Romans, from village to empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 413–414. ISBN 0-19-511875-8.

- ^ a b c d Castex 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Oetelaar, Taylor (2014). "Reconstructing the Baths of Caracalla". Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. 1 (2): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.daach.2013.12.002.

- ^ Castex 2008, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Rowan 2012, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Rowan 2012, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Oman, C. (1916). "The Decline and Fall of the Denarius in the Third Century A.D.". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. 16: 37–60. JSTOR 42663723.

- ^ Scott 2008, p. 130–131.

- ^ a b Scott 2008, p. 123.

- ^ a b Bergeron, David (2007–2008). "Roman Antoninianus". Bank of Canada Review.

- ^ Scott 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Harl, Kenneth (1996). Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700. JHU Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-801-85291-9.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: the Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press. p. 42.

- ^ Southern, Patricia (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Routledge. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-317-49694-6.

- ^ Scott 2008, p. 21.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 74. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ a b c Brauer, G. (1967). The Decadent Emperors: Power and Depravity in Third-Century Rome. p. 75.

- ^ a b c Christopher, Matthew (2015). An Invincible Beast: Understanding the Hellenistic Pike Phalanx in Action. Casemate Publishers. p. 403.

- ^ a b c d e Dunstan 2011, pp. 406–407.

- ^ see about Caracalla's planned visit to the shrine Frank Kolb: Literarische Beziehungen zwischen Cassius Dio, Herodian und der Historia Augusta, Bonn 1972, pp. 123ff.

- ^ Dio Cassius 79 (78),5,2-5. See, Herodian and 4.13 Historia Augusta, Caracalla 6.6-7.2. See also Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer, Ann Arbor, 1994, pp. 152-156.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 75. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- ^ Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2.

- ^ Hekster & Zair 2008, p. 59.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art: Portrait head of the Emperor Caracalla". acc. no. 40.11.1a".

- ^ Herodian of Antioch. History of the Roman Empire. pp. 4.7.3.

- ^ Dio, Cassius (n.d.). Roman History. pp. 78.11.1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Varner, Eric, R. (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. p. 169. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pangerl, Andreas (2013). Porträttypen des Caracalla und des Geta auf Römischen Reichsprägungen – Definition eines neuen Caesartyps des Caracalla und eines neuen Augustustyps des Geta. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt des RGZM Mainz 43. pp. 99–116.

- ^ Manders 2012, p. 251.

- ^ Manders 2012, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Varner, Eric (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. p. 184. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

- ^ a b c d Manders 2012, p. 226.

- ^ a b Manders 2012, p. 227.

- ^ Tuck, Steven L. (2014). A History of Roman Art. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4443-3026-7.

- ^ a b Mehl, Andreas (2011). Roman Historiography. John Wiley & Sons. p. 171.

- ^ Breisach, Ernst (2008). Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Third Edition. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-226-07284-5.

- ^ Hadas, Moses (2013). History of Latin Literature. Columbia University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-231-51487-3.

- ^ Leistner, M. W. L. (1966). The Greater Roman Historians. University of California Press. p. 180.

- ^ Schäfer, Peter (2003). The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. p. 55. ISBN 3-16-148076-7.

- ^ Scott, Andrew G. (2015). Cassius Dio, Caracalla, and the Senate. De Gruyter Publishers. p. 157.

- ^ a b c d Rowan 2012, p. 113.

- ^ Rowan 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Ashley, Mike (2012). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. Hachette UK. p. B21;P80. ISBN 978-1-4721-0113-6.

- ^ Wood, Susan (2010). "Caracalla and the French Revolution: A Roman tyrant in eighteenth-century iconography". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome.

- ^ a b Sillar, Shamus (2001). Quinquennium in provinciis: Caracalla and Imperial Administration 212–217. p. iii.

- ^ Agnew, John; Bidwell, Walter (1844). The Eclectic Magazine: Foreign Literature, Volume 2. Leavitt, Throw and Company. p. 217.

- ^ Magie, David (1950). Roman Rule in Asia Minor. Princeton University Press. p. 683.

- ^ Sillar, Shamus (2001). Quinquennium in provinciis: Caracalla and Imperial Administration 212–217. p. 127.

- ^ Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2.

- ^ Sillar, Shamus (2001). Quinquennium in provinciis: Caracalla and Imperial Administration 212–217. pp. 46–47.

- ^ Asante, Molefi K.; Ismail, Shaza (2016). "Interrogating the African Roman Emperor Caracalla: Claiming and Reclaiming an African Leader". Journal of Black Studies. 47: 41–52. doi:10.1177/0021934715611376. S2CID 147256542.

Sources

- Agnew, John; Bidwell, Walter (1844). The Eclectic Magazine: Foreign Literature. Vol. II. Leavitt, Throw and Company.

- Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2.

- Asante, Molefi K.; Shaza, Ismail (2016). "Interrogating the African Roman Emperor Caracalla: Claiming and Reclaiming an African Leader". Journal of Black Studies. 47: 41–52. doi:10.1177/0021934715611376. S2CID 147256542.

- Ashley, Mike (2012). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-4721-0113-6.

- Benario, Herbert (1954). "The Dediticii of the Constitutio Antoniniana". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 85: 188–196. doi:10.2307/283475. JSTOR 283475.

- Bergeron, David (2008). "Roman Antoninianus". Bank of Canada Review.

- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel, J; Talbert, Richard J.A (2004). The Romans, from village to empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511875-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brauer, G (1967). The Decadent Emperors: Power and Depravity in Third-Century Rome.

- Breisach, Ernst (2008). Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07284-5.

- Cairns, John (2007). Beyond Dogmatics: Law and Society in the Roman World: Law and Society in the Roman World. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3177-3.

- Castex, Jean (2008). Architecture of Italy. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32086-6.

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- Dio, Cassius. (n.d.). Roman History.

- Dunstan, William (2011). Ancient Rome. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7.

- Fisher, Warren (2010). The Illustrated History of the Roman Empire: From Caesar's Crossing the Rubicon (49 Bc) to Empire's Fall, 476 Ad. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-7739-6.

- Gagarin, Michael (2009). Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. (c 1136) Historia Regum Britanniae

- Gibbon, Edward. (1776). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 1.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: the Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press.

- Hadas, Moses (2013). History of Latin Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51487-3.

- Hammond, Mason (1957). "Imperial Elements in the Formula of the Roman Emperors during the First Two and a Half Centuries of the Empire". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 25: 19–64. doi:10.2307/4238646. JSTOR 4238646.

- Harl, Kenneth (1996). Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700. JHU Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-801-85291-9.

- Hekster, Olivier; Zair, Nicholas (2008). Debates and Documents in Ancient History: Rome and its Empire. EUP. ISBN 978-0-7486-2992-3.

- Herodian of Antioch. (n.d.) History of the Roman Empire.

- Johnson, Allan; Coleman-Norton, Paul; Bourne, Frank; Pharr, Clyde (1961). Ancient Roman Statutes: A Translation with Introduction, Commentary, Glossary, and Index. The Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 1-58477-291-3.

- Lavan, Myles (2016). "The Spread of Roman Citizenship, 14–212 CE: Quantification in the Face of High Uncertainty" (PDF). Past and Present (230): 3–46. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtv043. hdl:10023/12646.

- Leistner, M. W. L. (1966). The Greater Roman Historians. University of California Press.

- Levine, Lee (1975). Caesarea Under Roman Rule. Brill Archive. ISBN 90-04-04013-7.

- Lim, Richard (2010). The Edinburgh Companion to Ancient Rome and Greece: Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press.

- Magie, David (1950). Roman Rule in Asia Minor. Princeton University Press.

- Manders, Erika (2012). Impact of Empire: Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, A.D. 193–284. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-18970-6.

- Matthew, Christopher (2015). An Invincible Beast: Understanding the Hellenistic Pike Phalanx in Action. Casemate Publishers.

- Mehl, Andres (2011). Roman Historiography. John Wiley & Sons.

- Melton, Gordon, J. (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5000 Years of Religious History.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193–284. Impact of Empire. Vol. XII. Brill Academic. OCLC 859895124.

- Morgan, Robert (2016). History of the Coptic Orthodox People and the Church of Egypt. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-4602-8027-0.

- Oman, C (1916). The Decline and Fall of the Denarius in the Third Century A.D. Royal Numismatic Society.

- Oetelaar, Taylor (2014). "Reconstructing the Baths of Caracalla". Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural History.

- Pangerl, Andreas (2013). Porträttypen des Caracalla und des Geta auf Römischen Reichsprägungen – Definition eines neuen Caesartyps des Caracalla und eines neuen Augustustyps des Geta. RGZM Mainz.

- Rowan, Clare (2012). Under Divine Auspices: Divine Ideology and the Visualisation of Imperial Power in the Severan Period. Cambridge University Press.

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 3-16-148076-7.

- Scott, Andrew (2008). Change and Discontinuity Within the Severan Dynasty: The Case of Macrinus. Rutgers. ISBN 978-0-549-89041-6. OCLC 430652279.

- Scott, Andrew G. (2015). Cassius Dio, Caracalla and the Senate. De Gruyters.

- Sillar, Shamus (2001). Quinquennium in provinciis: Caracalla and Imperial Administration 212–217.

- Tuck, Steven L. (2014). A History of Roman Art. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3026-7.

- Southern, Patricia (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-49694-6.

- Tabbernee, William; Lampe, Peter (2008). Pepouza and Tymion: The Discovery and Archaeological Exploration of a Lost Ancient City and an Imperial Estate. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020859-7.

- Tuori, Kaius (2016). "Judge Julia Domna? A Historical Mystery and the Emergence of Imperial Legal Administration". The Journal of Legal History. 37 (2): 180–197. doi:10.1080/01440365.2016.1191590. S2CID 147778542.

- Varner, Eric (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

- Whittock, Martyn John; Whittock, Martyn (1991). The Roman Empire. Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 0-435-31274-X.

- Wood, Susan (2010). "Caracalla and the French Revolution: A Roman tyrant in eighteenth-century iconography". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome.

- Zoch, Paul (2000). Ancient Rome: An Introductory History. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-8061-3287-6.

External links

- Kettenhofen, Erich (1990). "CARACALLA". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 790–792.

- Life of Caracalla (Historia Augusta at LacusCurtius: Latin text and English translation)

- Cassius Dio, Historia Romana, Books 79–80

- Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus 21[usurped] (translation).

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. V (9th ed.). 1878. p. 81.

- For information on the caracallus garment, see William Smith Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: "Caracalla"

- Roman Currency of the Principate, from Tulane University (Archived 1 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine)