Marcel Janco

Marcel Janco | |

|---|---|

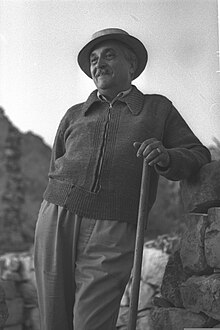

Janco in 1954 | |

| Born | Marcel Hermann Iancu 24 May 1895 |

| Died | 21 April 1984 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | Romanian, Israeli |

| Education | Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich |

| Known for | Oil painting, collage, relief, illustration, found object art, linocut, woodcut, watercolor, pastel, costume design, interior design, scenic design, ceramic art, fresco, tapestry |

| Movement | Postimpressionism, Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, Primitivism, Dada, Abstract art, Constructivism, Surrealism, Art Deco, Das Neue Leben, Contimporanul, Criterion, Ofakim Hadashim |

| Awards | |

Marcel Janco (German: [maʁˈsɛl ˈjaŋkoː], French: [maʁsɛl ʒɑ̃ko]; common rendition[a] of the Romanian name Marcel Hermann Iancu[1] [marˈtʃel ˈherman ˈjaŋku]; 24 May 1895 – 21 April 1984) was a Romanian and Israeli visual artist, architect and art theorist. He was the co-inventor of Dadaism and a leading exponent of Constructivism in Eastern Europe. In the 1910s, he co-edited, with Ion Vinea and Tristan Tzara, the Romanian art magazine Simbolul. Janco was a practitioner of Art Nouveau, Futurism and Expressionism before contributing his painting and stage design to Tzara's literary Dadaism. He parted with Dada in 1919, when he and painter Hans Arp founded a Constructivist circle, Das Neue Leben.

Reunited with Vinea, he founded Contimporanul, the influential tribune of the Romanian avant-garde, advocating a mix of Constructivism, Futurism and Cubism. At Contimporanul, Janco expounded a "revolutionary" vision of urban planning. He designed some of the most innovative landmarks of downtown Bucharest. He worked in many art forms, including illustration, sculpture and oil painting.

Janco was one of the leading Romanian Jewish intellectuals of his generation. Targeted by antisemitic persecution before and during World War II, he emigrated to the British Mandate for Palestine in 1941. He won the Dizengoff Prize and Israel Prize, and was a founder of Ein Hod, a utopian art colony.

Biography

Early life

Marcel Janco was born on 24 May 1895 in Bucharest to an upper middle class Jewish family.[2] His father, Hermann Zui Iancu, was a textile merchant. His mother, Rachel née Iuster, was from Moldavia.[3] The couple lived outside Bucharest's Jewish quarter, on Decebal Street.[4] He was the oldest of four children. His brothers were Iuliu (Jules) and George. His sister, Lucia, was born in 1900.[4] The Iancus moved from Decebal to Gândului Street, and then to Trinității, where they built one of the largest home-and-garden complexes in early 20th century Bucharest.[5] In 1980, Janco revisited his childhood years, writing: "Born as I was in beautiful Romania, into a family of well-to-do people, I had the fortune of being educated in a climate of freedom and spiritual enlightenment. My mother, [...] possessing a genuine musical talent, and my father, a stern man and industrious merchant, had created the conditions favorable for developing all of my aptitudes. [...] I was of a sensitive and emotional nature, a withdrawn child who was predisposed to dreaming and meditating. [...] I grew up [...] dominated by a strong sense of humanity and social justice. The existence of disadvantaged, weak, people, of impoverished workers, of beggars, hurt me and, when compared to our family's decent condition, awoke in me a feeling of guilt."[6]

Janco attended Gheorghe Șincai School and studied drawing art with the Romanian Jewish painter and cartoonist Iosif Iser.[7] In his teenage years, the family traveled widely, from Austria-Hungary to Switzerland, Italy and the Netherlands.[8] At Gheorghe Lazăr High School, he met several students who would become his artistic companions: Tzara (known then as S. Samyro), Vinea (Iovanaki), writers Jacques G. Costin and Poldi Chapier.[9] Janco also became friends with pianist Clara Haskil, the subject of his first published drawing, which appeared in Flacăra magazine in March 1912.[10][11]

As a group, the students were under the influence of Romanian Symbolist clubs, which were at the time the more radical expressions of artistic rejuvenation in Romania. Marcel and Jules Janco's first moment of cultural significance took place in October 1912, when they joined Tzara in editing the Symbolist venue Simbolul, which managed to receive contributions from some of Romania's leading modern poets, from Alexandru Macedonski to Ion Minulescu and Adrian Maniu. The magazine nevertheless struggled to find its voice, alternating modernism with the more conventional Symbolism.[12] Janco was perhaps the main graphic designer of Simbolul, and he may even have persuaded his wealthy parents to support the venture (which closed down in early 1913).[13] Unlike Tzara, who refused to look back on Simbolul with anything but embarrassment, Janco proudly regarded it as his first participation in artistic revolution.[14]

After the Simbolul moment, Marcel Janco worked at Seara daily, where he took further training in draftsmanship.[15] The newspaper took him in as illustrator, probably as a result of intercessions from Vinea, its literary columnist.[10] Their Simbolul colleague Costin joined them as Seara's cultural editor.[10][16] Janco was also a visitor of the literary and art club meeting at the home of controversial politician and Symbolist poet Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești, who was for a while the manager of Seara.[17]

It is possible that, during those years, Tzara and Janco first came to hear and be influenced by the absurdist prose of Urmuz, the lonesome civil clerk and amateur writer who would later become the hero of Romanian modernism.[18] Years later, in 1923, Janco drew an ink portrait of Urmuz.[19] In maturity, he also remarked that Urmuz was the original rebel figure in Romanian literature.[20] In the 1910s, Janco was also interested in the parallel development of French literature, and read passionately from such authors as Paul Verlaine and Guillaume Apollinaire.[21] Another immediate source of inspiration for his attitude on life was provided by Futurism, an anti-establishment movement created in Italy by poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his artists' circle.[22]

Swiss journey and Dada events

Janco eventually decided to leave Romania, probably because he wanted to attend international events such as the Sonderbund exhibit, but also because of quarrels with his father.[15] In quick succession after the start of World War I, Marcel, Jules and Tzara left Bucharest for Zürich. According to various accounts, their departure may have been either a search for new opportunities (abundant in cosmopolitan Switzerland)[23] or a discreet pacifist statement.[24] Initially, the Jancos were registered with the University of Zurich, where Marcel took Chemistry courses, before applying to study architecture at the Federal Institute of Technology.[25] His real ambition, later confessed, was to pursue more training in painting.[6][26] The two brothers were soon joined by younger Georges Janco, but all three were left without any financial support when the war began hampering Europe's trade routes; until October 1917, both Jules and Marcel (who found it impossible to sell his paintings) earned a living as cabaret performers.[26][27] Marcel was noted for performing selections from Romanian folklore and playing the accordion,[28] as well as for his rendition of chansons.[10][26] It was during this time that the young artist and his brothers began using the consecrated version of the surname Iancu, probably in hopes that it would sound more familiar to foreigners.[29]

In this context, the Romanians came into contact with Hugo Ball and the other independent artists plying their trade at the Malerei building, which soon after became known as Cabaret Voltaire. Ball later recalled that four "Oriental" men introduced themselves to him late after a show—the description refers to Tzara, the older Jancos and, probably, the Romanian painter Arthur Segal.[30] Ball found the young painter especially pleasant, and was impressed that, unlike his peers, Janco was melancholy rather than ironic; other participants remember him as a very handsome presence in the group, and he allegedly had the reputation of a "lady-killer".[31]

Accounts of what happened next differ, but it is presumed that, shortly after the four new participants were accepted, the performances became more daring, and the transition was made from Ball's Futurism to the virulent anti-art performances of Tzara and Richard Huelsenbeck.[32] With help from Segal and others, Marcel Janco was personally involved in decorating the Cabaret Voltaire.[28] Its hectic atmosphere would inspire Janco to create an eponymous oil painting, dated 1916 and believed to have been lost.[33] He was a major contributor to the cabaret's events: he notably carved the grotesque masks worn by performers on stilts, gave "hissing concerts" and, in unison with Huelsenbeck and Tzara, improvised some of the first (and mostly onomatopoeic) "simultaneous poems" to be read on stage.[34]

His work with masks became especially influential, opening up a new field of theatrical exploration for the Dadaists (as the Cabaret Voltaire crew began calling themselves), and earning special praise from Ball.[35] Contrary to Ball's later claim of authorship, Janco is also credited with having tailored the "bishop dress", another one of the iconic products of early Dadaism.[36] The actual birth of "Dadaism", at an unknown date, later formed the basis of disputes between Tzara, Ball, and Huelsenbeck. In this context, Janco is cited as a source for the story according to which the invention of the term "Dada" belonged exclusively to Tzara.[37] Janco also circulated stories according to which their shows were attended for informative purposes by communist theorist Vladimir Lenin[38] and psychiatrist Carl Jung.[26]

His various contributions were harnessed by Dada's international effort of self-promotion. In April 1917, he welcomed the Dada affiliation of Switzerland's own Paul Klee, calling Klee's contribution to the Dada exhibit a "great event".[39] His mask designs were popular beyond Europe, and inspired similar creations by Mexico's Germán Cueto, the "Stridentist" painter-puppeteer.[40] The Dadaist popularization effort received lukewarm responses in Janco's native country, where the traditionalist press expressed alarm at being confronted with Dada precepts.[41] Vinea himself was ambivalent about the activities of his two friends, preserving a link with poetic tradition which made his publication in Tzara's press impossible.[42] In a letter to Janco, Vinea spoke about having personally presented one of Janco's posters to modernist poet and art critic Tudor Arghezi: "[He] said, critically, that you cannot say whether a person is talented or not on the basis of only one drawing. Rubbish."[43]

Exhibited at the Dada group shows, Janco also illustrated the Dada advertisements, including an April 1917 program which features his sketches of Ball, Tzara and Ball's actress wife Emmy Hennings.[44] The event featured his production of Oskar Kokoschka's farce Sphinx und Strohmann, for which he was also the stage designer, and which was turned into one of the most notorious among Dada provocations.[45] Janco was the director and mask designer for the Dada production for another one of Kokoschka's plays, Job.[46] He also returned as Tzara's illustrator, producing the linocuts to The First Heavenly Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine, having already created the props for its theatrical production.[47]

"Two-speeds" Dada and Das Neue Leben

As early as 1917, Marcel Janco began taking his distance from the movement he had helped to generate. His work, in both woodcut and linocut, continued to be used as the illustration to Dada almanacs for another two years,[48] but he was more often than not in disagreement with Tzara, while also trying to diversify his style. As noted by critics, he found himself split between the urge to mock traditional art and the belief that something just as elaborate needed to take its place: in the conflict between Tzara's nihilism and Ball's art for art's sake, Janco tended to support the latter.[49] In a 1966 text, he further assessed that there were "two speeds" in Dada, and that the "spiritual violence" phase had eclipsed the "best Dadas", including his fellow painter Hans Arp.[50]

Janco recalled: "We [Janco and Tzara] couldn't agree any more on the importance of Dada, and the misunderstandings accumulated."[51] There were, he noted, "dramatic fights" sparked by Tzara's taste for "bad jokes and scandal".[52] The artist preserved a grudge, and his retrospective views on Tzara's role in Zürich are often sarcastic, depicting him as an excellent organizer and vindictive self-promoter, but not truly a man of culture;[53] a few years into the scandal, he even started a rumor that Tzara was illegally trading in opium.[54] As noted in 2007 by Romanian literary historian Paul Cernat: "All the efforts by Ion Vinea to reunite them [...] would be in vain. Iancu and Tzara would ignore (or banter) each other for the rest of their lives".[55] With this split, there came a certain classicization in Marcel Janco's discourse. In February 1918, Janco was even invited to lecture at his alma mater, where he spoke about modernism and authenticity in art as related phenomena, drawing comparisons between the Renaissance and African art.[56] However, having decided to focus on his other projects, Janco nearly abandoned his studies, and failed his final exam.[57]

In this context, he moved closer to the cell of post-Dada Constructivists exhibiting collectively as Neue Kunst ("New Art")—Arp, Fritz Baumann, Hans Richter, Otto Morach.[58] As a result, Janco was made a member of Das Neue Leben faction, which supported an educational approach to modern art, coupled with socialist ideals and Constructivist aesthetics.[59] In its art manifesto, the group declared its ideal of "rebuild[ing] the human community" in preparation for the end of capitalism.[60] Janco was even affiliated with Artistes Radicaux, a more politically inclined section of Das Neue Leben, where his colleagues included other former Dadas: Arp, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling.[61] The Artistes Radicaux were in touch with the German Revolution, and Richter, who worked for the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, even offered Janco and the others virtual teaching positions at the Academy of Fine Arts under a workers' government.[62]

Between Béthune and Bucharest

Janco made his final contribution to the Dada adventure in April 1919, when he designed the masks for a major Dada event organized by Tzara at the Saal zur Kaufleutern, and which degenerated into an infamous mass brawl.[63] By May, he was mandated by Das Neue Leben to create and publish a journal for the movement. Although this never saw print, the preparations placed Janco in contact with the representatives of various modernist currents: Arthur Segal, Walter Gropius, Alexej von Jawlensky, Oscar Lüthy and Enrico Prampolini.[64] This period also witnessed the start of a friendly relationship between Janco and the Expressionist artists who published in Herwarth Walden's magazine Der Sturm.[65]

A little more than a year after the end of war, in December 1919, Marcel and Jules left Switzerland for France. After passing through Paris, the painter was in Béthune, where he married Amélie Micheline "Lily" Ackermann, in what was described as a gesture of fronde against his father. The girl was a Swiss Catholic of lowly condition, who had first met the Jancos at Das Neue Leben.[66] Janco was probably in Béthune for a longer while: he was listed as one of those considered for helping to rebuild war-affected French Flanders, redesigned the Chevalier-Westrelin store in Hinges, and was perhaps the co-owner of an architectural enterprise, Ianco & Déquire.[67] It is not unlikely that Janco followed with curiosity the activities of Dada's Parisian cell, which were overseen by Tzara and his pupil André Breton, and he is known to have impressed Breton with his own architectural projects.[68] He was also announced, with Tzara, as a contributor to the post-Dada magazine L'Esprit Nouveau, published by Paul Dermée.[69] Nevertheless, Janco was invited to exhibit elsewhere, rallying with Section d'Or, a Cubist collective.[68]

Late in 1921, Janco and his wife left for Romania, where they had a second marriage to seal their union in front of familial disputes.[70] Janco was soon reconciled with his parents, and, although still unlicensed as an architect, began receiving his first commissions, some of which came from within his own family.[71][72] His first known design, constructed in 1922 and officially registered as the work of one I. Rosenthal, is a group of seven alley houses, 3 pairs and corner residence, on his father Hermann Iancu's property, at 79 Maximilian Popper Street (prev Trinității Street 29); one of these became his new home. Essentially traditional in style, they are also somewhat stylised, recalling the plainness of the English Arts & Crafts or the Czech 'Cubist' style.[73]

Soon after making his comeback, Marcel Janco reconnected himself with the local avant-garde salons, and had his first Romanian exhibits, at the Maison d'Art club in Bucharest.[74] His friends and collaborators, among them actress Dida Solomon and journalist-director Sandu Eliad, would describe him as exceptionally charismatic and knowledgeable.[75] In December 1926, he was present at the Hasefer Art Show in Bucharest.[76] Around that year, Janco took commissions as an art teacher at his studio in Bucharest—in the words of his pupil, the future painter Hedda Sterne, these were informal: "We were given easels, etc. but nobody looked, nobody advised us."[77]

Contimporanul beginnings

From his position as Constructivist mentor and international artist, Janco proceeded to network between Romanian modernist currents, and joined up with his old colleague Vinea. Early in 1922, the two men founded a political and art magazine, the influential Contimporanul—historically, the longest-lived venue of the Romanian avant-garde.[78] Janco was abroad that year, as one of guests at the First Constructivist Congress, convened by Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg in Düsseldorf.[79] He was in Zürich around 1923, receiving the visit of a compatriot, writer Victor Eftimiu, who declared him a hard-working artist able to reconcile the modern with the traditional.[80]

Contimporanul followed Janco's Constructivist affiliation. Initially a venue for socialist satire and political commentary, it reflected Vinea's strong dislike for the ruling National Liberal Party.[81] However, by 1923, the journal became increasingly cultural and artistic in its revolt, headlining with translations from van Doesburg and Breton, publishing Vinea's own homage to Futurism, and featuring illustrations and international notices which Janco may have handpicked himself.[82] Some researchers have attributed the change exclusively to the painter's growing say in editorial policy.[83][84] Janco was at the time in correspondence with Dermée, who was to contribute the Contimporanul anthology of modern French poetry,[85] and with fellow painter Michel Seuphor, who collected Janco's Constructivist sculptures.[86] He maintained a link between Contimporanul and Der Sturm, which republished his drawings alongside the contributions of various Romanian avant-garde writers and artists.[87] The reciprocal popularization was taken up by Ma, the Vienna-based tribune of Hungarian modernists, which also published samples of Janco's graphics.[88] Owing to Janco's resentments and Vinea's apprehension, the magazine never covered the issuing of new Dada manifestos, and responded critically to Tzara's new versions of Dada history.[89]

Marcel Janco also took charge of Contimporanul's business side, designing its offices on Imprimerie Street and overseeing the publication of postcards.[90] Over the years, his own contributions to Contimporanul came to include some 60 illustrations, some 40 articles on art and architectural topics, and a number of his architectural designs or photographs of buildings erected from them.[91] He oversaw one of the journal's first special issues, dedicated to "Modern Architecture", and notably hosting his own contributions to architectural theory, as well as his design of a "country workshop" for Vinea's use.[92] Other issues also featured his essay on film and theater, his furniture designs, and his interview with the French Cubist Robert Delaunay.[93] Janco was also largely responsible for the Contimporanul issue on Surrealism, which included his interviews with writers such as Joseph Delteil, and his inquiry about the publisher Simon Krà.[94]

Together with Romanian Cubist painter M. H. Maxy, Janco was personally involved in curating the Contimporanul International Art Exhibit of 1924.[95] This event reunited the major currents of Europe's modern art, reflecting Contimporanul's eclectic agenda and international profile. It hosted samples of works by leading modernists: the Romanians Segal, Constantin Brâncuși, Victor Brauner, János Mattis-Teutsch, Milița Petrașcu, alongside Arp, Eggeling, Klee, Richter, Lajos Kassák and Kurt Schwitters.[96] The exhibit included samples of Janco's work in furniture design, and featured his managerial contribution to a Dada-like opening party, co-produced by him, Maxy, Vinea and journalist Eugen Filotti.[97] He was also involved in preparing the magazine's theatrical parties, including the 1925 production of A Merry Death, by Nikolai Evreinov; Janco was the set and costume designer, and Eliad the director.[98] An unusual echo of the exhibit came in 1925, when Contimporanul published a photograph of Brâncuși's Princess X sculpture. The Romanian Police saw this as a sexually explicit artwork, and Vinea and Janco were briefly taken into custody.[99] Janco was a dedicated admirer of Brâncuși, visiting him in Paris and writing in Contimporanul about Brâncuși's "spirituality of form" theories.[100]

In their work as cultural campaigners, Vinea and Janco even collaborated with 75 HP, a periodical edited by poet Ilarie Voronca, which was nominally anti-Contimporanul and pro-Dada.[101] Janco was also an occasional presence in the pages of Punct, the Dadaist-Constructivist paper put out by the socialist Scarlat Callimachi. It was here that he notably published articles on architectural styles and a lampoon, in French and German, titled T.S.F. Dialogue entre le bourgeois mort et l'apôtre de la vie nouvelle ("Cablegram. The Dialogue between a Dead Bourgeois and the Apostle of New Living").[83][102] In addition, his graphic work was popularized by Voronca's other magazine, the Futurist tribune Integral.[103] Janco was also called upon by authors Ion Pillat and Perpessicius to illustrate their Antologia poeților de azi ("The Anthology of Present-Day Poets"). His portraits of the writers included, drawn in sharply modernist style, were received with amusement by the traditionalist public.[104] In 1926, Janco further antagonized the traditionalists by publishing sensual drawings for Camil Baltazar's book of erotic poems, Strigări trupești lîngă glezne ("Bodily Exhortations around the Ankles").[105]

Functionalist breakthrough

Some time in the late 1920s, Janco set up an architectural studio Birou de Studii Moderne (Office of Modern Studies), a partnership with his brother Jules (Iulius), a venture often identified by the name Marcel Iuliu Iancu, combining the two brothers as one.[106] Heralding the change of architectural tastes with his articles in Contimporanul, Marcel Janco described Romania's capital as a chaotic, inharmonious, backward town, in which the traffic was hampered by carts and trams, a city in need of Modernist revolution.[107]

Profiting from the building boom of Greater Romania, and the rising popularity of functionalism, Janco's Birou received commissions from 1926 onwards that were occasional and small-scale. Compared with mainstream functionalist architects like Horia Creangă, Duiliu Marcu or Jean Monda,[108] the Jancos had a decisive role in popularizing the functionalist versions of Constructivism or Cubism, designing the first examples of this new stylistic approach to be built in Romania. The first clear, though unheralded, expression of Modernism in Romania, was the construction in 1926 of a small apartment building near his earlier houses, also built for his father Herman, with an apartment for Herman, one for Marcel as well as his rooftop studio. The structure simply follows the curved line of the corner lot, the severe elevations devoid of decoration, enlivened only by a triangular bay window and balcony above, and a scheme of different colours (now lost) applied to the three wall areas differentiated by slight variations on depth.

A major breakthrough was his Villa for Jean Fuchs, built in 1927 on Negustori Street. Its cosmopolitan owner allowed the artist complete freedom in designing the building, and a budget of 1 million lei, and he created what is often described as the first Constructivist (and therefore Modernist) structure in Bucharest.[109][71] The design was quite unlike anything seen in Bucharest before, the front facade composed of complex overlapping, projecting and receding rectangular volumes, horizontal and corner windows, three circular porthole windows, and stepped flat roof areas including a rooftop lookout. The result caused a stir in the neighborhood, and the press found it to be reminiscent of a "morgue" and a "crematorium".[71] The architect and his patrons were undeterred by such reactions, and the Janco firm received commissions to build similar villas.

Until 1933, when Marcel Janco finally received his certification, his designs continued to be officially recorded under different names, most usually attributed to a Constantin Simionescu.[71] This had little effect on the Birou's output: by the time of his last known design in 1938, Janco and his brother are thought to have designed some 40 permanent or temporary structures in Bucharest, many in the wealthier northern residential districts of Aviatorilor and Primaverii, but by far the largest concentration in or to the north of the Jewish Quarter, just the east of the old town centre, reflecting the family and community ties of many of his commissions.[71]

A series of modernist villas for sometimes wealthy clients followed despite the Fuchs controversy.[110] The Villa Henri Daniel (1927, demolished) on Strada Ceres returned to the almost unadorned flat facade, enlivened by a play of horizontal and vertical lines, while the Maria Lambru Villa (1928), on Popa Savu Street, was a simplified version of the Fuchs design. The Florica Chihăescu house on Șoseaua Kiseleff (1929) is surprisingly formal with a central porch below strip windows, and also marks collaboration with Milița Petrașcu from the 1924 exhibition who provided some statuary (now lost).[111] The Villa Bordeanu (1930) on Labirint Street plays with symmetrical formality while the Villa Paul Iluta (1931, altered) employs bold rectangular volumes over three floors, as does the Paul Wexler Villa (1931), on Silvestru and Grigore Mora streets.[71] The Jean Juster Villa (1931) nearby at Strada Silvestru 75 combines the bold rectangular volumes with a projecting semi-circular one. Another project was a house for his Simbolul friend Poldi Chapier; located on Ipătescu Alley and finished in 1929,[71] this is occasionally described as "Bucharest's first Cubist lodging", even though the Villa Fuchs was two year earlier.[112] In 1931 he designed his first tenement/apartment building at Strada Caimatei 20, a small stack of 3 apartments of boldly projecting forms, developed himself for his family with other floors to rent, in the name of his wife Clara Janco. It is thought the studios for his Birou were on the top floor, and the design was published in Contimporanul in 1932.[113] Two more followed in 1933 on Strada Paleologu next to each other, simpler in conception, with a second one in his wife's name, and one for Jaques Costin - which features a bas relief panel of women working with wool by Militia Pătraşcu by the door.[114] These projects are joined by a private sanatorium of Predeal, Janco's only design outside of Bucharest. Built in 1934[115] at the base of a wooded hill, it has the sweeping horizontals of international streamlined Modernism, with Janco's innovation of diagonally placed rooms creating a striking zigzag effect.[109]

Janco had one daughter from his marriage to Lily Ackermann, who signed her name Josine Ianco-Starrels (b. 1926), and was raised a Catholic.[116] Her sister Claude-Simone had died in infancy.[117] By the mid-1920s, Marcel and Lily Janco were estranged: already by the time of their divorce (1930), she was living by herself in a Brașov home designed by Janco.[117] The artist remarried to Clara "Medi" Goldschlager, the sister of his old friend Jacques G. Costin. The couple had a girl, Deborah Theodora ("Dadi" for short).[117]

With his new family, Janco lived a comfortable life, traveling throughout Europe and spending his summer vacations in the resort town of Balchik.[117] The Jancos and the Costins also shared ownership of a country estate: known as Jacquesmara,[118] it was located in Budeni-Comana, Giurgiu County.[6][10] The house is especially known for hosting Clara Haskil during one of her triumphant returns to Romania.[10]

Between Contimporanul and Criterion

Janco was still active as the art editor of Contimporanul during its final and most eclectic series of 1929,[119] when he took part in selecting new young contributors, such as publicist and art critic Barbu Brezianu.[120] At that junction, the magazine triumphantly published a "Letter to Janco", in which the formerly traditionalist architect George Matei Cantacuzino spoke about his colleague's decade-long contribution to the development of Romanian functionalism.[71][121] Beyond his Contimporanul affiliation, Janco rallied with the Bucharest collective Arta Nouă ("New Art"), also joined by Maxy, Brauner, Mattis-Teutsch, Petrașcu, Nina Arbore, Cornelia Babic-Daniel, Alexandru Brătășanu, Olga Greceanu, Corneliu Michăilescu, Claudia Millian, Tania Șeptilici and others.[122]

Janco and some other regulars of Contimporanul also reached out to the Surrealist faction at unu review—Janco is notably mentioned as a "contributor" on the cover of unu, Summer 1930 issue, where all 8 containing pages were purposefully left blank.[123] Janco prepared woodcuts for the first edition of Vinea's novel Paradisul suspinelor ("The Paradise of Sobs"), printed with Editura Cultura Națională in 1930,[124][125] and for Vinea's poems in their magazine versions.[126] His drawings were used in illustrating two volumes of interviews with writers, compiled by Contimporanul sympathizer Felix Aderca,[127] and Costin's only volume of prose, the 1931 Exerciții pentru mâna dreaptă ("Right-handed Exercises").[124][128]

Janco attended the 1930 reunion organized by Contimporanul in honor of the visiting Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and gave a welcoming speech.[129] Marinetti was again praised by the Contimporanul group (Vinea, Janco, Petrașcu, Costin) in February 1934, in an open letter stating: "We are soldiers of the same army."[130] These developments created a definitive split in Romania's avant-garde movement, and contributed to Contimporanul's eventual fall: the Surrealists and socialists at unu condemned Vinea and the rest for having established, through Marinetti, a connection with the Italian fascists.[131] After the incidents, Janco's art was openly questioned by unu contributors such as Stephan Roll.[132]

Although Contimporanul went bankrupt, an artistic faction of the same name survived until 1936.[133] During the interval, Janco found other backers in the specialized art and architecture magazines, such as Orașul, Arta și Orașul, Rampa, Ziarul Științelor și al Călătoriilor.[71] In 1932, his villa designs were included by Alberto Sartoris in his guide to modern architecture, Gli elementi dell'architettura razionale.[71][134] The early 1930s also witnessed Janco's participation with the literary and art society Criterion, whose leader was philosopher Mircea Eliade. The group was mostly a venue Romania's intellectual youth, interested in redefining the national specificity around modernist values, but also offered a venue for dialogue between the far right and the far left.[135] With Maxy, Petrașcu, Mac Constantinescu, Petre Iorgulescu-Yor, Margareta Sterian and others, Janco represented the art collective at Criterion, which, in 1933, exhibited at Dalles Hall, Bucharest.[136] The same year, Janco erected a blockhouse for Costin (Paleologu Street, 5), which doubled as his own working address and the administrative office of Contimporanul.[71]

From 1929, Janco's efforts to reform the capital received administrative support from Dem. I. Dobrescu, the left-wing Mayor of Bucharest.[137] 1934 was the year when Janco returned as architectural theorist, with Urbanism, nu romantism ("Urbanism, Not Romanticism"), an essay in the review Orașul. Janco's text restated the need and opportunity for modernist urban planning, especially in Bucharest.[71] Orașul, edited by Eliad and writer Cicerone Theodorescu, introduced him as a world-famous architect and "revolutionary", praising the diversity of his contributions.[71] In 1935, Janco published the pamphlet Către o arhitectură a Bucureștilor ("Toward an Architecture of Bucharest"), which recommended a "utopian" project to solve the city's social crisis.[71][75] Like some of his Contimporanul colleagues, he was by then collaborating with Cuvântul Liber, the self-styled "moderate left-wing review" and with Isac Ludo's modernist magazine, Adam.[138]

The mid-1930s was his most prolific period as an architect, designing more villas, more small apartment buildings, and larger ones as well.[110] His Bazaltin Company headquarters, a mixed use project os offices and apartments that rose up to a topmost 9th floor on Jianu Square, his largest and most prominent, and still most well known (albeit abandoned), was built in 1935. The Solly Gold apartments on a corner on Hristo Botev Avenue (1934) is his best known smaller block, with interlocking angular volumes and balconies on all five sides visible, a double level apartment on the top, and a panel depicting Diana by Militia Pătraşcu by the door. Another well known design is the David Haimovici (1937) on Strada Olteni, its well kept smooth grey walls outlined in white, and a Mediterranean pergola on the top floor. The seven level Frida Cohen tower (1935) dominates a small roundabout on Stelea Spătarul Street with its curved balconies, while a six level one on Luchian Street, probably a real estate investment of his own,[139] is more restrained, with long strip windows the main feature, and another panel by Milita Petraşcu in the lobby. Villas included one for Florica Reich (1936) on Grigore Mora, a simple rectangular volume with a double-height corner cut-out topped by an inventive gridded glass roof, and one for Hermina Hassner (1937), almost square in plan, and with almost the opposite effect, a first floor corner balcony wall pierced by a grid of small circular openings.[71] Probably commissioned by Mircea Eliade, in 1935 Janco also designed the Alexandrescu Building, a severe four storey tenement for Eliade's sister and her family.[71] One of his last projects was a collaboration with Milita Petrascu for her family home and studio, the Villa Emil Pătraşcu (1937) at Pictor Ion Negulici Street 19, a boldly blocky design.[140]

Together with Margareta Sterian, who became his disciple, Janco was working on artistic projects involving ceramics and fresco.[141] In 1936, some works by Janco, Maxy and Petrașcu represented Romania at the Futurist art show in New York City.[142] Throughout the period, Janco was still on demand as a draftsman: in 1934, his depiction of poet Constantin Nissipeanu opened the first print of Nisspeanu's Metamorfoze;[143] in 1936, he published a posthumous portrait of writer Mateiu Caragiale, to illustrate the Perpessicius edition of Caragiale's poems.[144] His prints also served to illustrate Sadismul adevărului ("The Sadism of Truth"), written by unu founder Sașa Pană.[145]

Persecution and departure

By that time, the Janco family was faced with the rise of antisemitism, and alarmed by the growth of fascist movements such as the Iron Guard. In the 1920s, the Contimporanul leadership had sustained a xenophobic attack from the traditionalist review Țara Noastră. It cited Vinea's Greek origins as a cause for concern,[146] and described Janco as the "painter of the cylinder", and an alien, cosmopolitan, Jew.[147] That objection to Janco's work, and to Contimporanul in general, was also taken up in 1926 by the anti-modernist essayist I. E. Torouțiu.[148] Criterion itself split in 1934, when some of its members openly rallied with the Iron Guard, and the radical press accused the remaining ones of promoting pederasty through their public performances.[149] Josine was expelled from Catholic school in 1935, the reason invoked being that her father was a Jew.[150]

For Marcel Janco, the events were an opportunity to discuss his own assimilation into Romanian society: in one of his conferences, he defined himself as "an artist who is a Jew", rather than "a Jewish artist".[150] He later confessed his dismay at the attacks targeting him: "nowhere, never, in Romania or elsewhere in Europe, during peacetime or the cruel years of [World War I], did anyone ask me whether I was a Jew or... a kike. [...] Hitler's Romanian minions managed to change this climate, to turn Romania into an antisemitic country."[6] The ideological shift, he recalled, destroyed his relationships with the Contimporanul poet Ion Barbu, who reportedly concluded, after admiring a 1936 exhibit: "Too bad you're a kike!"[6] At around that time, pianist and fascist sympathizer Cella Delavrancea also assessed that Janco's contribution to theater was the prime example of "Jewish" and "bastard" art.[151]

When the antisemitic National Christian Party took power, Janco was coming to terms with the Zionist ideology, describing the Land of Israel as the "cradle" and "salvation" of Jews the world over.[6][152] At Budeni, he and Costin hosted Betar paramilitaries, who were attempting to organize a Jewish self-defense movement.[6] Janco subsequently made his first trip to British Palestine, and began arranging his and his family's relocation there.[6][118][152][153] Although Jules and his family emigrated soon after the visit, Marcel returned to Bucharest and, shortly before Jewish art was officially censored, had his one last exhibit there, together with Milița Petrașcu.[118] He was also working on one of his last, and most experimental, contributions to Romanian architecture: the Hermina Hassner Villa (which also hosted his 1928 painting of the Jardin du Luxembourg), the Emil Petrașcu residence,[71] and a tower behind the Atheneum.[154]

In 1939, the Nazi-aligned Ion Gigurtu cabinet enforced racial discrimination throughout the land, and, as a consequence, Jaquesmara was confiscated by the state.[118] Many of the Bucharest villas he had designed, which had Jewish landlords, were also taken over forcefully by the authorities.[71] Some months after, the National Renaissance Front government prevented Janco from publishing his work anywhere in Romania, but he was still able to find a niche at Timpul daily—its anti-fascist manager, Grigore Gafencu, gave imprimatur to sketches, including the landscapes of Palestine.[153] He was also finding work with the ghettoized Jewish community, designing the new Barașeum Studio, located in the vicinity of Caimatei.[153]

During the first two years of World War II, although he prepared his documents and received a special passport,[155] Janco was still undecided. He was still in Romania when the Iron Guard established its National Legionary State. He was receiving and helping Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe, and hearing from them about the concentration camp system, but refused offers to emigrate into a neutral or Allied country.[6] His mind was made up in January 1941, when the Iron Guard's struggle for maintaining power resulted in the Bucharest Pogrom. Janco himself was a personal witness to the violent events, noting for instance that the Nazi German bystanders would declare themselves impressed by the Guard's murderous efficiency, or how the thugs made an example of the Jews trapped in the Choral Temple.[156] The Străulești Abattoir murders and the stories of Jewish survivors also inspired several of Janco's drawings.[157] One of the victims of the Abattoir massacre was Costin's brother Michael Goldschlager. He was kidnapped from his house by Guardsmen,[6] and his corpse was among those found hanging on hooks, mutilated in such way as to mock the Jewish kashrut ritual.[152][158]

Janco later stated that, over the course of a few days, the pogrom had made him a militant Jew.[6][159] With clandestine assistance from England,[6] Marcel, Medi and their two daughters left Romania through Constanța harbor, and arrived in Turkey on 4 February 1941. They then made their way to Islahiye and French Syria, crossing through the Kingdom of Iraq and Transjordan, and, on 23 February, ended their journey in Tel Aviv.[160] The painter found his first employment as architect for Tel Aviv's city government, sharing the office with a Holocaust survivor who informed him about the genocide in occupied Poland.[6] In Romania, the new regime of Conducător Ion Antonescu planned a new series of antisemitic measures and atrocities (see Holocaust in Romania). In November 1941, Costin and his wife Laura, who had stayed behind in Bucharest, were among those deported to the occupied region of Transnistria.[160] Costin survived, joining up with his sister and with Janco in Palestine, but later moved back to Romania.[161]

In British Palestine and Israel

During his years in British Palestine, Marcel Janco became a noted participant in the development of local Jewish art. He was one of the four Romanian Jewish artists who marked the development of Zionist arts and crafts before 1950—the others were Jean David, Reuven Rubin, Jacob Eisenscher;[162] David, who was Janco's friend in Bucharest, joined him in Tel Aviv after an adventurous trip and internment in Cyprus.[163] In particular, Janco was an early influence on three Zionist artists who had arrived to Palestine from other regions: Avigdor Stematsky, Yehezkel Streichman and Joseph Zaritsky.[164] He was soon recognized as a leading presence in the artist community, receiving Tel Aviv Municipality's Dizengoff Prize in 1945, and again in 1946.[165]

These contacts were not interrupted by the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and Janco was a figure of prominence in the art scene of independent Israel. The new nation enlisted his services as planner, and he was assigned to the team of Arieh Sharon, being tasked with designing and preserving the Israeli national parks.[166] As a result of his intervention, in 1949 the area of Old Jaffa was turned into an artist-friendly community.[166] He was again a recipient of the Dizengoff Prize in 1950 and 1951, resuming his activity as an art promoter and teacher, with lectures at the Seminar HaKibbutzim college (1953).[165] His artwork was again on show in New York City for a 1950 retrospective.[152] In 1952 he was one of three artists whose work was displayed at the Israeli pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the first year Israel had its own pavilion at the Biennale. The other two artists were Reuven Rubin and Moshe Mokady.[167]

Marcel Janco began his main Israeli project in May 1953, after he had been mandated by the Israeli government to prospect the mountainous regions and delimit a new national park south of Mount Carmel.[168] In his own account (since disputed by others),[166] he came across the deserted village of Ein Hod, whose Palestinian inhabitants had been largely displaced during the 1948 expulsion. Janco felt that the place should not be demolished, obtaining a lease on it from the authorities, and rebuilt the place with other Israeli artists who worked there on weekends;[169] Janco's main residence continued to be in the neighborhood of Ramat Aviv.[154] His plot of land in Ein Hod was previously owned by the Arab Abu Faruq, who died in 1991 at the Jenin refugee camp.[170] Janco became the site's first mayor, reorganizing it into a utopian society, art colony and tourist attraction, and instituted the strict code of requirements for one's settlement in Ein Hod.[171]

Also in the 1950s, Janco was a founding member of Ofakim Hadashim ("New Horizons") group, comprising Israeli painters committed to abstract art, and headed by Zaritsky. Although he shared the artistic vision, Janco probably did not approve of Zaritsky's rejection of all narrative art and, in 1956, left the group.[172][173] He continued to explore new media, and, together with artisan Itche Mambush, he created a series of reliefs and tapestries.[154][174] Janco also drew in pastel, and created humorous illustrations to Don Quixote.[155]

His individual contributions received further praise from his peers and his public: in 1958, he was honored with the Histadrut union's prize.[165] Over the next two decades, Marcel Janco had several new personal exhibits, notably in Tel Aviv (1959, 1972), Milan (1960) and Paris (1963).[152] Having attended the 1966 Venice Biennale,[175] he won the Israel Prize of 1967, in recognition of his work as painter.[152][165][166][174][176]

In 1960, Janco's presence in Ein Hod was challenged by the returning Palestinians, who tried to reclaim the land. He organized a community defense force, headed by sculptor Tuvia Iuster, which guarded Ein Hod until Israel Police intervened against the protesters.[177] Janco was generally tolerant of those Palestinians who set up the small rival community of Ein Hawd: he notably maintained contacts with tribal leader Abu Hilmi and with Arab landscape artist Muin Zaydan Abu al-Hayja, but the relationship between the two villages was generally distant.[178] Janco has also been described as "disinterested" in the fate of his Arab neighbors.[166]

For a second time, Janco reunited with Costin when the latter fled Communist Romania. The writer was a political refugee, singled out at home for "Zionist" activities, and implicated in the show trial of Milița Petrașcu.[128][179] Costin later left Israel, settling in France.[10][180] Janco himself made efforts to preserve a link with Romania, and sent albums to his artist friends beyond the Iron Curtain.[181] He met with folklorist and former political prisoner Harry Brauner,[175] poet Ștefan Iureș, painter Matilda Ulmu and art historian Geo Șerban.[154][155] His studio was home to other Jewish Romanian emigrants fleeing communism, including female artist Liana Saxone-Horodi.[154][174] From Israel, he spoke about his Romanian experience at length, first in an interview with writer Solo Har and then in a 1980 article for Shevet Romania magazine.[6] A year later, from his home in Australia, the modernist promoter Lucian Boz headlined a selection of his works with Janco's portrait of the author.[182]

Also in 1981, a selection of Janco's drawings of Holocaust crimes was issued with the Am Oved album Kav Haketz/On the Edge.[6] The following year, he received the "Worthy of Tel Aviv" distinction, granted by the city government.[165] One of the last public events to be attended by Marcel Janco was the creation of the Janco-Dada Museum at his home in Ein Hod.[71][152][154][174][176] By then, Janco is said to have been concerned about the overall benefits of Jewish relocation into an Arab village.[183] Among his final appearances in public was a 1984 interview with Schweizer Fernsehen station, in which he revisited his Dada activities.[26]

Work

From Iser's Postimpressionism to Expressionist Dada

The earliest works by Janco show the influence of Iosif Iser, adopting the visual trappings of Postimpressionism and illustrating, for the first time in Janco's career, the interest in modern composition techniques;[184] Liana Saxone-Horodi believes that Iser's manner is most evident in Janco's 1911 work, Self-portrait with Hat, preserved at the Janco-Dada Museum.[174] Around 1913, Janco was in more direct contact with the French sources of Iser's Postimpressionism, having by then discovered on his own the work of André Derain.[15] However, his covers and vignettes for Simbolul are generally Art Nouveau and Symbolist to the point of pastiche. Researcher Tom Sandqvist presumes that Janco was in effect following his friends' command, as "his own preferences were soon closer to Cézanne and cubist-influenced modes of expression".[185]

Futurism was thrown into the mix, a fact acknowledged by Janco during his 1930 encounter with Marinetti: "we were nourished by [Futurist] ideas and empowered to be enthusiastic."[22] A third major source for Janco's imagery was Expressionism, initially coming to him from both Die Brücke artists and Oskar Kokoschka,[186] and later reactivated by his contacts at Der Sturm.[65] Among his early canvasses, the self-portraits and the portraits of clowns have been discussed as particularly notable samples of Romanian Expressionism.[187]

The influence of Germanic Postimpressionism on Janco's art was crystallized during his studies at the Federal Institute of Technology. His more important teachers there, Sandqvist observes, were sculptor Johann Jakob Graf and architect Karl Moser—the latter in particular, for his ideas on the architectural Gesamtkunstwerk. Sandqvist suggests that, after modernizing Moser's ideas, Janco first theorized that Abstract-Expressionistic decorations needed to an integral part of the basic architectural design.[188] In paintings from Janco's Cabaret Voltaire period, the figurative element is not canceled, but usually subdued: the works show a mix of influences, primarily from Cubism or Futurism, and have been described by Janco's colleague Arp as "zigzag naturalism".[189] His series on dancers, painted before 1917 and housed by the Israel Museum, moves between the atmospheric qualities of a Futurism filtered through Dada and Janco's first experiments in purely abstract art.[190]

His assimilation of Expressionism has led scholar John Willett to discuss Dadaism as visually an Expressionist sub-current,[191] and, in retrospect, Janco himself claimed that Dada was not as much a fully-fledged new artistic style as "a force coming from the physical instincts", directed against "everything cheap".[192] However, his own work also features the quintessentially Dada found object art, or everyday objects rearranged as art—reportedly, he was the first Dadaist to experiment in such manner.[193] His other studies, in collage and relief, have been described by reviewers as "a personal synthesis which is identifiable as his own to this day",[194] and ranked among "the most courageous and original experiments in abstract art."[71]

The Contimporanul years were a period of artistic exploration. Although a Constructivist architect and designer, Janco was still identifiable as an Expressionist in his ink-drawn portraits of writers and in some of his canvasses. According to scholar Dan Grigorescu, his essays of the time fluctuate away from Constructivism, and adopt ideas common in Expressionism, Surrealism, or even the Byzantine revival suggested by anti-modernist reviews.[195] His Rolling the Dice piece is a meditation on the tragedy of human existence, which reinterprets the symbolism of zodiacs[196] and probably alludes to the seedier side of urban life.[197] The Expressionist transfiguration of shapes was especially noted in his drawings of Mateiu Caragiale and Stephan Roll, created from harsh and seemingly spontaneous lines.[186] The style was ridiculed at the time by traditionalist poet George Topîrceanu, who wrote that, in Antologia poeților de azi, Ion Barbu looked "a Mongolian bandit", Felix Aderca "a shoemaker's apprentice", and Alice Călugăru "an alcoholic fishwife".[104] Such views were contrasted by Perpessicius' publicized belief that Janco was "the purest artist", his drawings evidencing the "great vital force" of his subjects.[198] Topîrceanu's claim is contradicted by literary historian Barbu Cioculescu, who finds the Antologia drawings: "exquisitely synthetic—some of them masterpieces; take it from someone who has seen from up close many of the writers portrayed".[199]

Primitive and collective art

As a Dada, Janco was interested in the raw and primitive art, generated by "the instinctive power of creation", and he credited Paul Klee with having helped him "interpret the soul of primitive man".[39][200] A distinct application of Dada was his own work with masks, seen by Hugo Ball as having generated fascination with their unusual "kinetic power", and useful for performing "larger-than-life characters and passions."[201] However, Janco's understanding of African masks, idols and ritual was, according to art historians Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, "deeply romanticized" and "reductive".[202]

At the end of the Dada episode, Janco also took his growing interest in primitivism to the level of academia: in his 1918 speech at the Zürich Institute, he declared that African, Etruscan, Byzantine and Romanesque arts were more genuine and "spiritual" than the Renaissance and its derivatives, while also issuing special praise for the modern spirituality of Derain, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse; his lecture rated all Cubists above all Impressionists.[203] In his contribution to Das Neue Leben theory, he spoke about a return to the handicrafts, ending the "divorce" between art and life.[204] Art critic Harry Seiwert also notes that Janco's art also reflected his contact with various other alternative models, found in Ancient Egyptian and Far Eastern art, in the paintings of Cimabue and El Greco, and in Cloisonnism.[205] Seiwert and Sandqvist both propose that Janco's work had other enduring connections with the visual conventions of Hassidism and the dark tones often favored by 20th-century Jewish art.[206]

Around 1919, Janco had come to describe Constructivism as a needed transition from "negative" Dada, an idea also pioneered by his colleagues Kurt Schwitters and Theo van Doesburg, and finding an early expression in Janco's plaster relief Soleil jardin clair (1918).[207] In part, Janco's post-Dadaism responded to the socialist ideals of Constructivism. According to Sandqvist, his affiliation to Das Neue Leben and his sporadic contacts with the Art Soviet of Munich meant that he was trying to "adjust to the spirit of the age."[208] Historian Hubert F. van der Berg also notes that the socialist ideal of "a new life", implicitly adopted by Janco, was a natural peacetime development of Dada's discourse about "the new man".[209]

The activity at Contimporanul cemented Janco's belief in primitivism and the values of outsider art. In a 1924 piece, he argued: "The art of children, folk art, the art of psychopaths, of primitive people are the liveliest ones, the most expressive ones, coming to us from organic depths, without cultivated beauty."[210] He ridiculed, like Ion Vinea before him, the substance of Romania's academic traditionalism, notably in a provocative drawing which showed a grazing donkey under the title "Tradition".[211] Instead, Janco was publicizing the idea that Dada and various other strands of modernism were the actual tradition, for being indirectly indebted to the absurdist nature of Romanian folklore.[212] The matter of Janco's own debt to his country's peasant art is more controversial. In the 1920s, Vinea discussed Janco's Cubism is a direct echo of an old abstract art that is supposedly native and exclusive to Romania—an assumption considered exaggerated by Paul Cernat.[213] Seiwert suggests that virtually none of Janco's paintings show a verifiable contact with Romanian primitivism, but his opinion is questioned by Sandqvist: he writes that Janco's masks and prints are homages to traditional Romanian decorative patterns.[214]

Beyond Constructivism

For a while, Janco rediscovered himself in abstract and semi-abstract art, describing the basic geometrical shapes as pure forms, and art as the effort to organize these forms—ideas akin with the "picto-poetry" of Romanian avant-garde writers such as Ilarie Voronca.[215] After 1930, when Constructivism lost its position of leadership on Romania's artistic scene,[83][216] Janco made a return to "analytic" Cubism, echoing the early work of Picasso in his painting Peasant Woman and Eggs.[186] This period centered on semi-figurative cityscapes, which, according to critics such as Alexandru D. Broșteanu[76] and Sorin Alexandrescu,[217] stand out for their objectification of the human figure. Also then, Janco worked on seascape and still life canvasses, in brown tones and Cubist arrangements.[174] Diversification touched his other activities. His theory of set design still mixed Expressionism into Futurism and Constructivism, calling for an actor-based Expressionist theater and a mechanized, movement-based, cinema.[218] However, his parallel work in costume design evidenced a toning down of avant-garde tendencies (to the displeasure of his colleagues at Integral magazine), and a growing preoccupation with commedia dell'arte.[219]

In discussing architecture, Janco described himself and the other Artistes Radicaux as the mentors of Europe's modernist urban planners, including Bruno Taut and the Bauhaus group.[220] The ideals of collectivism in art, "art as life", and a "Constructivist revolution" dominated his programmatic texts of the mid-1920s, which offered as examples the activism of De Stijl, Blok and Soviet Constructivist architecture.[221] His own architectural work was entirely dedicated to functionalism: in his words, the purpose of architecture was a "harmony of forms", with designs as simplified as to resemble crystals.[222] His experiment on Trinității Street, with its angular pattern and multicolored facade, has been rated one of the most spectacular samples of Romanian modernism,[71] while the buildings he designed later came with Art Deco elements, including the "ocean liner"-type balconies.[181] At the other end, his Predeal sanatorium was described by Sandqvist as "a long, narrow white building clearly signaling its function as a hospital" and "smoothly adapting to the landscape."[109] Functionalism was further illustrated by Janco's ideas on furniture design, where he favored "small heights", "simple aesthetics", as well as "a maximum of comfort"[223] which would "pay no tribute to richness".[71]

Scholars have also noted that "the breath of humanitarianism" unites the work of Janco, Maxy and Corneliu Michăilescu, beyond their shared eclecticism.[224] Cernat nevertheless suggests that the Contimporanul group was politically disengaged and making efforts to separate art from politics, giving positive coverage to both Marxism and Italian fascism.[225] In that context, a more evidently Marxist form of Constructivism, close to Proletkult, was being taken up independently by Maxy.[83] Janco's functionalist goal was still coupled with socialist imagery, as in Către o arhitectură a Bucureștilor, called an architectural tikkun olam by Sandqvist.[75] Indebted to Le Corbusier's New Architecture,[226] Janco theorized that Bucharest had the "luck" of not yet being systematized or built-up, and that it could be easily turned into a garden city, without ever repeating the West's "chain of mistakes".[71] According to architecture historians Mihaela Criticos and Ana Maria Zahariade, Janco's creed was not in fact radically different from mainstream Romanian opinions: "although declaring themselves committed to the modernist agenda, [Janco and others] nuance it with their own formulas, away from the abstract utopias of the International Style."[227] A similar point is made by Sorin Alexandrescu, who attested a "general contradiction" in Janco's architecture, that between Janco's own wishes and those of his patrons.[217]

Holocaust art and Israeli abstractionism

Soon after his first visit to Palestine and his Zionist conversion, Janco began painting landscapes in optimistic tones, including a general view over Tiberias[174] and bucolic watercolors.[176] By the time of World War II, however, he was again an Expressionist, fascinated with the major existential themes. The war experience inspired his 1945 painting Fascist Genocide, which is also seen by Grigorescu as one of his contributions to Expressionism.[228] Janco's sketches of the Bucharest Pogrom are, according to cultural historian David G. Roskies, "extraordinary" and in complete break with Janco's "earlier surrealistic style"; he paraphrases the rationale for this change as: "Why bother with surrealism when the world itself has gone crazy?"[159] According to the painter's own definition: "I was drawing with the thirst of one who is being chased around, desperate to quench it and find his refuge."[6] As he recalled, these works were not well received in the post-war Zionist community, because they evoked painful memories in a general mood of optimism; as a result, Janco decided to change his palette and tackle subjects which related exclusively to his new country.[229] An exception to this self-imposed rule was the motif of "wounded soldiers", which continued to preoccupy him after 1948, and was also thematically linked to the wartime massacres.[230]

During and after his Ofakim Hadashim engagement, Marcel Janco again moved into the realm of pure abstraction, which he believed represented the artistic "language" of a new age.[231] This was an older idea, as first illustrated by his 1925 attempt to create an "alphabet of shapes", the basis for any abstractionist composition.[83] His subsequent preoccupations were linked to the Jewish tradition of interpreting symbols, and he reportedly told scholar Moshe Idel: "I paint in Kabbalah".[232] He was still eclectic beyond abstractionism, and made frequent returns to brightly colored, semi-figurative, landscapes.[174] Also eclectic is Janco's sparse contribution to the architecture of Israel, including a Herzliya Pituah villa that is entirely built in the non-modernist Poble Espanyol style.[166] Another component of Janco's work was his revisiting of earlier Dada experiments: he redid some of his Dada masks,[174] and supported the international avant-garde group NO!art.[233] He later worked on the Imaginary Animals cycle of paintings, inspired by the short stories of Urmuz.[174][215]

Meanwhile, his Ein Hod project was in various ways the culmination of his promotion of folk art, and, in Janco's own definition, "my last Dada activity".[204] According to some interpretations, he may have been directly following the example of Hans Arp's "Waggis" commune, which existed in 1920s Switzerland.[55][154] Anthropologist Susan Slyomovics argues that the Ein Hod project as a whole was an alternative to the standard practice of Zionist colonization, since, instead of creating new buildings in the ancient scenery, it showed attempts to cultivate the existing Arab-style masonry.[234] She also writes that Janco's landscapes of the place "romanticize" his own contact with the Palestinians, and that they fail to clarify whether he thought of Arabs as refugees or as fellow inhabitants.[235] Journalist Esther Zanberg describes Janco as an "Orientalist" driven by "the mythology surrounding Israeli nationalistic Zionism."[166] Art historian Nissim Gal also concludes: "the pastoral vision of Janco [does not] include any trace of the inhabitants of the former Arab village".[173]

Legacy

Admired by his contemporaries on the avant-garde scene, Marcel Janco is mentioned or portrayed in several works by Romanian authors. In the 1910s, Vinea dedicated him the poem "Tuzla", which is one of his first contributions to modernist literature;[236] a decade later, one of the Janco exhibits inspired him to write the prose poem Danțul pe frânghie ("Dancing on a Wire").[237] Following his conflict with the painter, Tzara struck out all similar dedications from his own poems.[55] Before their friendship waned, Ion Barbu also contributed a homage to Janco, referring to his Constructivist paintings as "storms of protractors".[124] In addition, Janco was dedicated a poem by Belgian artist Émile Malespine, and is mentioned in one of Marinetti's poetic texts about the 1930 visit to Romania,[238] as well as in the verse of neo-Dadaist Valery Oisteanu.[239] Janco's portrait was painted by colleague Victor Brauner, in 1924.[124]

According to Sandqvist, there are three competing aspects in Janco's legacy, which relate to the complexity of his profile: "In Western cultural history Marcel Janco is best known as one of the founding members of Dada in Zürich in 1916. Regarding the Romanian avant-garde in the interwar period Marcel Hermann Iancu is more known as the spider in the web and as the designer of a great number of Romania's first constructivist buildings [...]. On the other hand, in Israel Marcel Janco is best known as the 'father' of the artists' colony of Ein Hod [...] and for his pedagogic achievements in the young Jewish state."[240] Janco's memory is principally maintained by his Ein Hod museum. The building was damaged by the 2010 forest fire, but reopened and grew to include a permanent exhibit of Janco's art.[174] Janco's paintings still have a measurable impact on the contemporary Israeli avant-garde, which is largely divided between the abstractionism he helped introduce and the neorealistic disciples of Michail Grobman and Avraham Ofek.[241]

The Romanian communist regime, which cracked down on modernism, reconfirmed the confiscation of villas built by the Birou de Studii Moderne, which it then leased to other families.[71][134] One of these lodgings, the Wexler Villa, was assigned as the residence of communist poet Eugen Jebeleanu.[134][242] The regime tended to ignore Janco's contributions, which were not listed in the architectural who's who,[243] and it became standard practice to generally omit references to his Jewish ethnicity.[6] He was however honored with a special issue of Secolul 20 literary magazine, in 1979,[154] and interviewed for Tribuna and Luceafărul journals (1981, 1984).[244] His architectural legacy was affected by the large-scale demolition program of the 1980s. Most of the buildings were spared, however, because they are scattered throughout residential Bucharest.[181] Some 20 of his Bucharest structures were still standing twenty years later,[243] but the lack of a renovation program and the shortages of late communism brought steady decay.[71][166][181][243]

After the Romanian Revolution of 1989, Marcel Janco's buildings were subject to legal battles, as the original owners and their descendants were allowed to contest the nationalization.[71] These landmarks, like other modernist assets, became treasured real estate: in 1996, a Janco house was valued at 500,000 United States dollars.[181] The sale of such property happened at a fast pace, reportedly surpassing the standardized conservation effort, and experts noted with alarm that Janco villas were being defaced with anachronistic additions, such as insulated glazing[243][245] and structural interventions,[134] or eclipsed by the newer highrise.[246] In 2008, despite calls from within the academic community, only three of his buildings had been inscribed in the National Register of Historic Monuments.[243]

Janco was again being referenced as a possible model for new generations of Romanian architects and urban planners. In a 2011 article, poet and architect August Ioan claimed: "Romanian architecture is, apart from its few years with Marcel Janco, one that has denied itself experimentation, projective thinking, anticipation. [...] it is content with imports, copies, nuances or pure and simple stagnation."[247] This stance is contrasted by that of designer Radu Comșa, who argues that praise for Janco often lacks "the recoil of objectivity".[163] Janco's programmatic texts on the issue were collected and reviewed by historian Andrei Pippidi in the 2003 retrospective anthology București – Istorie și urbanism ("Bucharest. History and Urban Planning").[248] Following a proposal formulated by poet and publicist Nicolae Tzone at the Bucharest Conference on Surrealism, in 2001,[249] Janco's sketch for Vinea's "country workshop" was used in designing Bucharest's ICARE, the Institute for the Study of the Romanian and European Avant-garde.[250] The Bazaltin building was used as the offices of TVR Cultural station.[243]

In the realm of visual arts, curators Anca Bocăneț and Dana Herbay organized a centennial Marcel Janco exhibit at the Bucharest Museum of Art (MNAR),[251] with additional contributions from writer Magda Cârneci.[181] In 2000, his work was featured in the "Jewish Art of Romania" retrospective, hosted by Cotroceni Palace.[252] The local art market rediscovered Janco's art, and, in June 2009, one of his seascapes sold in auction for 130,000 Euro, the second largest sum ever fetched by a painting in Romania.[253] There was a noted increase in his overall market value,[254] and he became interesting to art forgers.[255]

Outside Romania, Janco's work has been reviewed in specialized monographs by Harry Seiwert (1993)[256] and Michael Ilk (2001).[124][257] His work as painter and sculptor has been dedicated special exhibits in Berlin,[124] Essen (Museum Folkwang) and Budapest,[257] while his architecture was presented abroad with exhibitions at the Technical University Munich and Bauhaus Center Tel Aviv.[166] Among the events showcasing Janco's art, some focused exclusively on his rediscovered Holocaust paintings and drawings. These shows include On the Edge (Yad Vashem, 1990)[6] and Destine la răscruce ("Destinies at Crossroads", MNAR, 2011).[258] His canvasses and collages went on sale at Bonhams[176] and Sotheby's.[194]

See also

Notes

- ^ Surname also Ianco, Janko or Jancu.

References

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 66, 68, 69

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 69, 172, 300, 333, 377

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 69, 79

- ^ a b Sandqvist, p. 69

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 69, 103

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r (in Romanian) Vlad Solomon, "Confesiunea unui mare artist", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 559, January 2011

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 69–70

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 72

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 72–73

- ^ a b c d e f g (in Romanian) Geo Șerban, "Un profil: Jacques Frondistul", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 144, November 2002

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 188

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 48–54, 100, 412; Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (I)", p. 9; Sandqvist, pp. 4, 7, 29-30, 75-78, 81, 196

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 50, 100; Sandqvist, pp. 73–75

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 77, 141, 209, 263. See also Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (I)", p. 9

- ^ a b c Sandqvist, p. 78

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 34, 188

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 39

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 227, 234

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 226

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 235

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 67, 78

- ^ a b Sandqvist, p. 237

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 26, 78, 125

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 113, 132

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 111–112, 130; Sandqvist, pp. 78–80

- ^ a b c d e (in Romanian) Alina Mondini, "Dada trăiește", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 261, March 2005

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 26, 66, 78-79, 190

- ^ a b Cernat, Avangarda, p. 112

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 26, 66

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 31. See also Cernat, Avangarda, p. 112

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 66–67, 97

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 112–116; Sandqvist, pp. 31–32

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 27, 81

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 32, 35–36, 66–67, 84, 87, 189–190, 253, 259, 261, 265, 300, 332. See also Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 111–113, 155; Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (I)", p. 9

- ^ Harris Smith, pp. 6, 44

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 37, 40, 90, 253, 332. See also Cernat, Avangarda, p. 115

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 116; Sandqvist, p. 153

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 34

- ^ a b Kay Larson, "Art. Signs and Symbols", in New York Magazine, 2 March 1987, p. 96

- ^ Deborah Caplow, Leopoldo Méndez: Revolutionary Art and the Mexican Print, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2007, p. 38. ISBN 978-0-292-71250-8

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 124–126, 129

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 120–124

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 122; Sandqvist, p. 84

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 42, 84

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 90–91, 261

- ^ Harris Smith, pp. 43–44

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 84, 147

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 93

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 115, 130, 155, 160-162; Sandqvist, pp. 93–94

- ^ Nicholas Zurbrugg, The Parameters of Postmodernism, Taylor & Francis e-library, 2003, p. 83. ISBN 0-203-20517-0

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 94

- ^ Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (I)", p. 9

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 144

- ^ (in Romanian) Andrei Oișteanu, "Scriitorii români și narcoticele (6). Avangardiștii" Archived 5 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, in Revista 22, Nr. 952, June 2008

- ^ a b c Cernat, Avangarda, p. 130

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 80–81

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 81, 84

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 95

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 95–97, 190, 264, 342–343; Van der Berg, pp. 139, 145–147. See also Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 130, 155, 160-161

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 96. See also Van der Berg, p. 147

- ^ Van der Berg, pp. 147–148. See also Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 160–161

- ^ Van der Berg, p. 139

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 91–92. See also Harris Smith, p. 6

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 97, 190, 342–343

- ^ a b Grigorescu, p. 389

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 97–99

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 98–99, 340

- ^ a b Sandqvist, p. 98

- ^ Meazzi, p. 122

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 99

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Doina Anghel, Urban Route. Marcel Iancu: The Beginnings of Modern Architecture in Bucharest, E-cart.ro Association, 2008

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 99, 340

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 340, 344

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 178

- ^ a b c Sandqvist, p. 343

- ^ a b Aurel D. Broșteanu, "Cronica artistică. Expoziția inaugurală Hasefer", in Viața Românească, Nr. 12/1926, p. 414

- ^ Joan Simon, "Hedda Sterne", in Art in America, 1 February 2007

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 131–132; Sandqvist, p. 345

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 155, 164; Sandqvist, p. 341

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 93–94

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 130–145, 232–233; Sandqvist, pp. 343, 348–349

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 140–147, 157–158, 215–218, 245–268, 410–411; Sandqvist, pp. 345–348, 350. See also Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (I)", pp. 9–10

- ^ a b c d e (in Romanian) Mariana Vida, "Ipostaze ale modernismului (II)", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 504, December 2009

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 130, 145–146, 157–158, 161–162, 178, 216; Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (I)", pp. 9–10

- ^ Meazzi, p. 123

- ^ Prat, pp. 99, 104

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 222

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 247

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 130, 217–218

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 350–351

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 350

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 162–164

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 166–169

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 216–217

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 157; Grigorescu, p. 389; Sandqvist, pp. 351–354

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 157; Sandqvist, p. 351

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 351–352

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 159; Sandqvist, p. 351

- ^ (in Romanian) Ioana Paverman, "Pop Culture", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 436, August 2008; Nicoleta Zaharia, Dan Boicea, "Erotismul clasicilor", in Adevărul Literar și Artistic, 8 October 2008

- ^ Cristian R. Velescu, "Brâncuși and the Significance of Matter" Archived 3 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, in Plural Magazine Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Nr. 11/2001

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 357

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 160–161; Pop, "Un 'misionar al artei noi' (II)", p. 10

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 154; Sandqvist, p. 371

- ^ a b George Topîrceanu, Scrieri, Vol. II, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1983, pp. 360–361. OCLC 10998949

- ^ (in Romanian) Gheorghe Grigurcu, "Despre pornografie" Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, in România Literară, Nr. 2/2007

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 340–341

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 103. See also Cernat, Avangarda, p. 219

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 217, 341–342

- ^ a b c Sandqvist, pp. 341–342

- ^ a b "IANCU, Marcel". A Century of Romanian Architecture. Fundatia Culturala META. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "(in Romanian) Villa Florica Chihăescu Marcel Iancu, 1930". Via Bucuresti. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 49, 100

- ^ "Marcel Iancu - Urban Route" (PDF). E-cart.ro Association. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Marcel Janco and Modernist Bucharest". Adrian Yekes. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "About Us". SANATORIUL DE NEVROZE PREDEAL. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Sandqvist, pp. 97–98, 340, 377

- ^ a b c d Sandqvist, p. 340

- ^ a b c d Sandqvist, p. 378

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 169–171

- ^ (in Romanian) Filip-Lucian Iorga, "Barbu Brezianu" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, in România Literară, Nr. 3/2008

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 170–171

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 179. See also Grigorescu, p. 442

- ^ (in Romanian) Ioana Pârvulescu, "Nonconformiștii" Archived 7 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, in România Literară, Nr. 26/2001

- ^ a b c d e f (in Romanian) Geo Șerban, "Marcel Iancu la Berlin", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 92, November 2011

- ^ (in Romanian) Simona Vasilache, "Avangarda înapoi!" Archived 11 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, in România Literară, Nr. 19/2006

- ^ (in Romanian) Paul Cernat, "Avangarda maghiară în Contimporanul" Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, in Apostrof, Nr. 12/2006

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 313–314; Crohmălniceanu, p. 618

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Paul Cernat, "Urmuziene și nu numai. Plagiatele 'urmuziene' ale unui critic polonez. Recuperarea lui Jacques G. Costin", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 151, January 2003

- ^ Sandqvist, p. 237. See also Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 174, 176

- ^ Giovanni Lista, Marinetti et le futurisme, L'Âge d'Homme, Lausanne, 1977, p. 239. ISBN 2-8251-2414-1

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, pp. 177, 229–232, 241–244

- ^ (in Romanian) Geo Șerban, "Ascensiunea lui Dolfi Trost", in Observator Cultural, Nr. 576, May 2011

- ^ Cernat, Avangarda, p. 179

- ^ a b c d (in Romanian) Andrei Pippidi, "În apărarea lui Marcel Iancu" Archived 4 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, in Dilema Veche, Nr. 357, December 2010

- ^ Ornea, pp. 149–156