Manikyala Stupa

| Manikyala Stupa | |

|---|---|

Manikyala Stupa in 2007 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Buddhism |

| Location | |

| Location | Tope Mankiala Punjab Pakistan |

| State | Punjab |

| Geographic coordinates | 33°26′53″N 73°14′36″E / 33.44806°N 73.24333°E |

The Manikyala Stupa (Urdu: مانكياله اسٹوپ) or Mankiala Stupa is a Buddhist stupa near the village of Tope Mankiala, in the Pothohar region of Pakistan's Punjab province. The stupa was built to commemorate the spot, where according to the Jataka tales, an incarnation of the Buddha called Prince Sattva sacrificed himself to feed seven hungry tiger cubs.[1][2]

Location

Mankiala stupa is located in the village of Tope Mankiala, near the place named Sagri and 2nd near the village of Sahib Dhamyal. It is 36 km southeast of Islamabad, and near the city of Rawalpindi. It is visible from the nearby historic Rawat Fort.

Significance

The stupa was built to commemorate the spot, where according to the Jataka tales, the Golden Light Sutra and popular belief, Prince Sattva, an earlier incarnation of the Buddha, sacrificed some of his body parts to feed seven hungry tiger cubs.[1][3]

History

The stupa is said to have been built during the reign of Kanishka between 128 and 151 CE.[4]

An alternate theory suggest that the stupa is one of 84 such buildings, built during the reign of Mauryan emperor Ashoka to house the ashes of the Buddha.[5] It is said that Emperor Kanishka used to visit this stupa often to pay respects to Buddha during his campaigns.[4]

The stupa was discovered by Mountstuart Elphinstone, the first British emissary to Afghanistan, in 1809– a detailed account of which is in his memoir Kingdom of Caubul (1815).[6]

The stupa contains an engraving which indicates that the stupa was restored in 1891.[4]

Relics

Mankiala stupa's relic deposits were discovered by Jean-Baptiste Ventura in 1830. The relics were then removed from the site during the British Raj, and are now housed in the British Museum.[9]

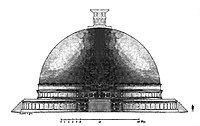

- Restored elevation of the stupa– scale 50 ft. to 1 in– showing where the relics were found

- Manikyala relics – Principal deposit

- Manikyala relics – First discovery

- Manikiala hoard – British Museum

Inscription

On one of the stones of the stupa there is an inscription which reads as:[10][11]

| Inscription | Original (Kharosthi script) | Transliteration | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | 𐨯𐨎 𐩄 𐩃 𐩃 𐨀𐨅𐨟𐨿𐨪 𐨤𐨂𐨪𐨿𐨬𐨀𐨅 𐨨𐨱𐨪𐨗𐨯 𐨐𐨞𐨅 | Saṃ 10 4 4 etra purvae maharajasa Kaṇe- | In the year 18, of the great king |

| Line 2 | 𐨮𐨿𐨐𐨯 𐨒𐨂𐨮𐨣𐨬𐨭𐨯𐨎𐨬𐨪𐨿𐨢𐨐 𐨫𐨫 | ṣkasa Guṣanavaśasaṃvardhaka Lala | Kanishka, Lala, increaser of the Kusana line, |

| Line 3 | 𐨡𐨜𐨞𐨩𐨒𐨆 𐨬𐨅𐨭𐨿𐨤𐨭𐨁𐨯 𐨐𐨿𐨮𐨟𐨿𐨪𐨤𐨯 | daḍaṇayago Veśpaśisa kṣatrapasa | judge, the Satrap Veśpaśi's |

| Line 4 | 𐨱𐨆𐨪𐨨𐨂𐨪𐨿𐨟𐨆 𐨯 𐨟𐨯 𐨀𐨤𐨣𐨒𐨅 𐨬𐨁𐨱𐨪𐨅 | horamurto sa tasa apanage vihare | donation master - he is in his own monastery |

| Line 5 | 𐨱𐨆𐨪𐨨𐨂𐨪𐨿𐨟𐨆 𐨀𐨅𐨟𐨿𐨪 𐨞𐨞𐨧𐨒𐨬𐨦𐨂𐨢𐨰𐨬 | horamurto etra ṇaṇabhagavabudhazava | the donation master - here several relics of the Lord, the Buddha, |

| Line 6 | 𐨤𐨿𐨪𐨟𐨁𐨯𐨿𐨟𐨬𐨩𐨟𐨁 𐨯𐨱 𐨟𐨀𐨅𐨣 𐨬𐨅𐨭𐨿𐨤𐨭𐨁𐨀𐨅𐨞 𐨑𐨂𐨡𐨕𐨁𐨀𐨅𐨣 | pratistavayati saha taena Veśpaśieṇa Khudaciena | establishes, together with the group of three, Veśpaśia, Khudacia, and |

| Line 7 | 𐨦𐨂𐨪𐨁𐨟𐨅𐨞 𐨕 𐨬𐨁𐨱𐨪𐨐𐨪𐨵𐨀𐨅𐨞 | Buriteṇa ca viharakaravhaeṇa | Burita, the builder of the monastery, |

| Line 8 | 𐨯𐨎𐨬𐨅𐨞 𐨕 𐨤𐨪𐨁𐨬𐨪𐨅𐨞 𐨯𐨢 𐨀𐨅𐨟𐨅𐨞 𐨐𐨂 | saṃveṇa ca parivareṇa sadha eteṇa ku- | and together with his whole retinue. Through this |

| Line 9 | 𐨭𐨫𐨨𐨂𐨫𐨅𐨣 𐨦𐨂𐨢𐨅𐨱𐨁 𐨕 𐨮𐨬𐨀𐨅𐨱𐨁 𐨕 | śalamulena budhehi ca ṣavaehi ca | root of good as well as through the Buddhas and disciples |

| Line 10 | 𐨯𐨨𐨎 𐨯𐨡 𐨦𐨬𐨟𐨂 | samaṃ sada bhavatu | may it always be |

| Line 11 | 𐨧𐨿𐨪𐨟𐨪𐨯𐨿𐨬𐨪𐨦𐨂𐨢𐨁𐨯 𐨀𐨒𐨿𐨪𐨤𐨜𐨁𐨀𐨭𐨀𐨅 | Bhratarasvarabudhisa agrapaḍiaśae | for the best share of (his) brother Svarabudhi. |

| Line 12 | 𐨯𐨢 𐨦𐨂𐨢𐨁𐨫𐨅𐨣 𐨣𐨬𐨐𐨪𐨿𐨨𐨁𐨒𐨅𐨞 | sadha Budhilena navakarmigeṇa | Together with Budhila, the superintendent of construction. |

| Line 13 | 𐨐𐨪𐨿𐨟𐨁𐨩𐨯 𐨨𐨰𐨅 𐨡𐨁𐨬𐨯𐨅𐨁 𐩅 | Kartiyasa maze divase 20 | On the 20th day of the month Kārttika. |

Conservation

The stupa has not been restored since 1891,(during british rule) and remains largely abandoned.[4] The stupa features a large defect in its mound, which was created by plunderers.

In 2024 - local influential and wealthy businessman & Philanthropist Mr. Ahmer Sajjad Khan undertook major renovation and rehabilitation work to restore the historic site and spent millions from his personal wealth for the restoration project. The outcome showed the “AK” effect and the efforts and philanthropic work of Mr. Ahmer were highly praised by locals as well as Buddhist community globally.

Access

Mankiala's stupa is located near the Mankiala Road in the village of Tope Mankiala. Towards the west, the Mankiala Road intersects the N-5 National Highway, which provides access to Islamabad and Rawalpindi. The site can also be accessed by the Mankiala railway station in the nearby village of Mankiala, which is served by the Karachi–Peshawar Railway Line.

Gallery

- Present-day view of Mankiala Stupa

- View of the stupa showing columnades

- Columnade

- Capital detail

See also

- Takht Bahi

- Gandhara

- Taxila

- Dharmarajika Stupa – largest of the stupas which form the Ruins of Taxila.

References

- ^ a b Bernstein, Richard (2001). Ultimate Journey: Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk who Crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment. A.A. Knopf. ISBN 9780375400094. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

Mankiala tiger.

- ^ Cunningham, Sir Alexander (1871). Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65. Government Central Press. p. 155.

As Buddha offers his body to appease the hunger of the seven starving tiger - cubs , so Râsâlu offers himself instead of the woman's only son who was destined to ... Lastly , the scene of both legends is laid at Manikpur or Mânikyâla

- ^ Golden Light Sutra 18.

- ^ a b c d "The forgotten Mankiala Stupa". Dawn. 26 October 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ Malik, Iftikhar Haider (2006). Culture and Customs of Pakistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-313-33126-8.

- ^ Michon, Daniel (12 August 2015). Archaeology and Religion in Early Northwest India: History, Theory, Practice. Routledge. pp. 28–31. ISBN 978-1-317-32458-4.

- ^ "دیومالائی روایتوں سے منسوب منکیالہ کا تاریخی سٹوپا". Independent Urdu (in Urdu). 6 April 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Ali, Ammad (10 July 2022). "The forgotten stupa | Footloose | thenews.com.pk". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ The British Museum Collection

- ^ Prinsep, H. T. (1844). Note on the Historical Results, Deducible from Recent Discoveries in Afghanistan. London: W. H. Allen & Co. p. Plate XVI.

- ^ Jongeward, David; Errington, Elizabeth; Salomon, Richard; Baums, Stefan (2012). "Catalog and Revised Text and Translations of Gandhāran Reliquary" (PDF). Gandhāran Buddhist Reliquaries. Seattle: Early Buddhist Manuscripts Project. pp. 240–242. ISBN 978-0-295-99236-5.