Manichaeism

| Manichaeism | |

|---|---|

| آیینِ مانی 摩尼教 | |

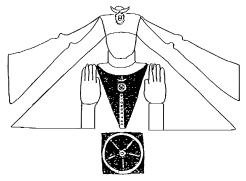

Sealstone of Mani, rock crystal, possibly 3rd century CE, Iraq. Cabinet des Médailles, Paris.[1][2] The seal reads "Mani, messenger of the messiah", and may have been used by Mani himself to sign his epistles.[3][1] | |

| Type | Universal religion |

| Classification | Iranian religion |

| Scripture | Manichaean scripture |

| Theology | Dualistic |

| Region | Historical: Europe, East Asia, Central Asia, West Asia, North Africa, Siberia Current: Fujian, Zhejiang |

| Language | Middle Persian, Classical Syriac, Parthian, Classical Latin, Classical Chinese, Old Uyghur language, Tocharian B, Sogdian language, Greek |

| Founder | Mani |

| Origin | 3rd century AD Parthian, Sasanian Empire |

| Separated from | Jewish Christian Elcesaite sect, and the teachings of Jesus, Buddha, and Zoroaster |

| Separations | |

Manichaeism (/ˌmænɪˈkiːɪzəm/;[4] in Persian: آئین مانی Āʾīn-ī Mānī; Chinese: 摩尼教; pinyin: Móníjiào) is a former major world religion,[5] founded in the 3rd century CE by the Parthian[6] prophet Mani (216–274 CE), in the Sasanian Empire.[7]

Manichaeism teaches an elaborate dualistic cosmology describing the struggle between a good, spiritual world of light, and an evil, material world of darkness.[8] Through an ongoing process that takes place in human history, light is gradually removed from the world of matter and returned to the world of light, whence it came. Mani's teaching was intended to "combine",[9] succeed, and surpass the teachings of Platonism,[10][11] Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Marcionism,[9] Hellenistic and Rabbinic Judaism, Gnostic movements, Ancient Greek religion, Babylonian and other Mesopotamian religions,[12] and mystery cults.[13][14] It reveres Mani as the final prophet after Zoroaster, the Buddha and Jesus.

Manichaeism was quickly successful and spread far through Aramaic-speaking regions.[15] It thrived between the third and seventh centuries, and at its height was one of the most widespread religions in the world. Manichaean churches and scriptures existed as far east as China and as far west as the Roman Empire.[16] It was briefly the main rival to early Christianity in the competition to replace classical polytheism before the spread of Islam. Under the Roman Dominate, Manichaeism was persecuted by the Roman state and was eventually stamped out in the Roman Empire.[5]

Manichaeism survived longer in the east than it did in the west. The religion was present in the Middle East into the Abbasid Caliphate period in the 10th century. It was also present in China despite increasingly strict proscriptions under the Tang dynasty and was the official religion of the Uyghur Khaganate until its collapse in 830. It experienced a resurgence under the Mongol Yuan dynasty during the 13th and 14th centuries but was subsequently banned by the Chinese emperors, and Manichaeism there became subsumed into Buddhism and Taoism.[17] Some historic Manichaean sites still exist in China, including the temple of Cao'an in Jinjiang, Fujian, and the religion may have influenced later movements in Europe, including Paulicianism, Bogomilism, and Catharism.

While most of Manichaeism's original writings have been lost, numerous translations and fragmentary texts have survived.[18]

An adherent of Manichaeism is called a Manichaean, Manichean, or Manichee.[19]

History

Life of Mani

Mani was an Iranian[20][21][a] born in 216 CE in or near Ctesiphon (now al-Mada'in, Iraq) in the Parthian Empire. According to the Cologne Mani-Codex,[22] Mani's parents were members of the Jewish Christian Gnostic sect known as the Elcesaites.[23]

Mani composed seven works, six of which were written in the late-Aramaic Syriac language. The seventh, the Shabuhragan,[24] was written by Mani in Middle Persian and presented by him to Sasanian emperor Shapur I. Although there is no proof Shapur I was a Manichaean, he tolerated the spread of Manichaeism and refrained from persecuting it within his empire's boundaries.[25]

According to one tradition, Mani invented the unique version of the Syriac script known as the Manichaean alphabet[26] that was used in all of the Manichaean works written within the Sasanian Empire, whether they were in Syriac or Middle Persian, as well as most of the works written within the Uyghur Khaganate. The primary language of Babylon (and the administrative and cultural language of the Empire) at that time was Eastern Middle Aramaic, which included three main dialects: Jewish Babylonian Aramaic (the language of the Babylonian Talmud), Mandaean (the language of Mandaeism), and Syriac, which was the language of Mani as well as the Syriac Christians.[27]

While Manichaeism was spreading, existing religions such as Zoroastrianism were still prevalent, and Christianity was gaining social and political influence. Although having fewer adherents, Manichaeism won the support of many high-ranking political figures. With the assistance of the Sasanian Empire, Mani began missionary expeditions. After failing to win the favour of the next generation of Persian royalty and incurring the disapproval of the Zoroastrian clergy, Mani is reported to have died in prison awaiting execution by the Persian emperor Bahram I. The date of his death is estimated at 276–277 CE.

Influences

Mani believed that the teachings of Buddha, Zoroaster,[28] and Jesus were incomplete, and that his revelations were for the entire world, calling his teachings the "Religion of Light". Manichaean writings indicate that Mani received revelations when he was twelve years old and again when he was 24, and over this period, he grew dissatisfied with the Elcesaites, the Jewish Christian Gnostic sect he was born into.[29] Some researchers also point to an important Jain influence on Mani as extreme degrees of asceticism and some specific features of Jain doctrine made the influence of Mahāvīra's religious community more plausible than even the Buddha.[30] Fynes (1996) argues that various Jain influences, particularly ideas on the existence of plant souls, were transmitted from Western Kshatrapa territories to Mesopotamia and then integrated into Manichaean beliefs.[31]

Mani wore colorful clothing abnormal for the time that reminded some Romans of a stereotypical Persian magus or warlord, earning him ire from the Greco-Roman world because of it.[32]

Mani taught how the soul of a righteous individual returns to Paradise upon dying, but "the soul of the person who persisted in things of the flesh – fornication, procreation, possessions, cultivation, harvesting, eating of meat, drinking of wine – is condemned to rebirth in a succession of bodies."[33]

Mani began preaching at an early age and was possibly influenced by contemporary Babylonian-Aramaic movements such as Mandaeism, Aramaic translations of Jewish apocalyptic works similar to those found at Qumran (e.g., the Book of Enoch literature), and by the Syriac dualist-Gnostic writer Bardaisan (who lived a generation before Mani). With the discovery of the Mani-Codex, it also became clear that he was raised in the Jewish Christian sect of the Elcasaites and possibly influenced by their writings.[citation needed]

According to biographies preserved by ibn al-Nadim and the Persian polymath al-Biruni, Mani received a revelation as a youth from a spirit, whom he would later call his "Twin" (Imperial Aramaic: תאומא tɑʔwmɑ, from which is also derived the Greek name of Thomas the Apostle, Didymus; the "twin"), Syzygos (Koinē Greek: σύζυγος "spouse, partner", in the Cologne Mani-Codex), "Double," "Protective Angel," or "Divine Self." This spirit taught him wisdom that he then developed into a religion. It was his "Twin" who brought Mani to self-realization. Mani claimed to be the Paraclete of the Truth promised by Jesus in the New Testament.[34]

Manichaeism's views on Jesus are described by historians:

Jesus in Manichaeism possessed three separate identities:

(1) Jesus the Luminous,

(2) Jesus the Messiah and

(3) Jesus patibilis (the suffering Jesus).

(1) As Jesus the Luminous ... his primary role was as supreme revealer and guide and it was he who woke Adam from his slumber and revealed to him the divine origins of his soul and its painful captivity by the body and mixture with matter.

(2) Jesus the Messiah was an historical being who was the prophet of the Jews and the forerunner of Mani. However, the Manichaeans believed he was wholly divine, and that he never experienced human birth, as the physical realities surrounding the notions of his conception and his birth filled the Manichaeans with horror. However, the Christian doctrine of virgin birth was also regarded as obscene. Since Jesus the Messiah was the light of the world, where was this light, they reasoned, when Jesus was in the womb of the Virgin? Jesus the Messiah, they believed, was truly born only at his baptism, as it was on that occasion that the Father openly acknowledged his sonship. The suffering, death and resurrection of this Jesus were in appearance only as they had no salvific value but were an exemplum of the suffering and eventual deliverance of the human soul and a prefiguration of Mani's own martyrdom.

(3) The pain suffered by the imprisoned Light-Particles in the whole of the visible universe, on the other hand, was real and immanent. This was symbolized by the mystic placing of the Cross whereby the wounds of the passion of our souls are set forth. On this mystical Cross of Light was suspended the Suffering Jesus (Jesus patibilis) who was the life and salvation of Man. This mystica crucifixio was present in every tree, herb, fruit, vegetable and even stones and the soil. This constant and universal suffering of the captive soul is exquisitely expressed in one of the Coptic Manichaean psalms.[35]

Augustine of Hippo also noted that Mani declared himself to be an "apostle of Jesus Christ".[36] Manichaean tradition is also noted to have claimed that Mani was the reincarnation of religious figures from previous eras such as the Buddha, Krishna, and Zoroaster in addition to Jesus himself.

Academics note that much of what is known about Manichaeism comes from later 10th- and 11th-century Muslim historians like al-Biruni and ibn al-Nadim in his al-Fihrist; the latter "ascribed to Mani the claim to be the Seal of the Prophets."[37] However, given the Islamic milieu of Arabia and Persia at the time, it stands to reason that Manichaens would regularly assert in their evangelism that Mani, not Muhammad, was the "Seal of the Prophets".[38] In reality, for Mani the metaphorical expression "Seal of Prophets" is not a reference to his finality in a long succession of prophets as it is used in Islam, but rather as final to his followers (who testify or attest to his message as a "seal").[39][40]

Other sources of Mani's scripture were the Aramaic originals of the Book of Enoch, 2 Enoch, and an otherwise unknown section of the Book of Enoch entitled The Book of Giants. Mani quoted the latter directly and expanded upon it, becoming one of the six original Syriac writings of the Manichaean Church. Besides short references by non-Manichaean authors through the centuries, no original sources of The Book of Giants (which is actually part six of the Book of Enoch) were available until the 20th century.[41]

Scattered fragments of both the original Aramaic Book of Giants (which were analyzed and published by Józef Milik in 1976)[42] and the Manichaean version of the same name (analyzed and published by Walter Bruno Henning in 1943)[43] were discovered along with the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Judaean desert in the 20th century and the Manichaean writings of the Uyghur Manichaean kingdom in Turpan. Henning wrote in his analysis of them:

It is noteworthy that Mani, who was brought up and spent most of his life in a province of the Persian empire, and whose mother belonged to a famous Parthian family, did not make any use of the Iranian mythological tradition. There can no longer be any doubt that the Iranian names of Sām, Narīmān, etc., that appear in the Persian and Sogdian versions of the Book of the Giants, did not figure in the original edition, written by Mani in the Syriac language.[43]

By comparing the cosmology of the books of Enoch to the Book of Giants, as well as the description of the Manichaean myth, scholars have observed that the Manichaean cosmology can be described as being based, in part, on the description of the cosmology developed in detail within the Enochic literature.[44] This literature describes the being that the prophets saw in their ascent to Heaven as a king who sits on a throne at the highest of the heavens. In the Manichaean description, this being, the "Great King of Honor", becomes a deity who guards the entrance to the World of Light placed at the seventh of ten heavens.[45] In the Aramaic Book of Enoch, the Qumran writings, overall, and in the original Syriac section of Manichaean scriptures quoted by Theodore bar Konai,[46] he is called malkā rabbā d-iqārā ("the Great King of Honor").[citation needed]

Mani was also influenced by writings of the gnostic Bardaisan (154–222 CE), who, like Mani, wrote in Syriac and presented a dualistic interpretation of the world in terms of light and darkness in combination with elements from Christianity.[47]

Mani was heavily inspired by Iranian Zoroastrian theology.[28]

Noting Mani's travels to the Kushan Empire (several religious paintings in Bamyan are attributed to him) at the beginning of his proselytizing career, Richard Foltz postulates Buddhist influences in Manichaeism:

Buddhist influences were significant in the formation of Mani's religious thought. The transmigration of souls became a Manichaean belief, and the quadripartite structure of the Manichaean community, divided between male and female monks (the "elect") and lay followers (the "hearers") who supported them, appears to be based on that of the Buddhist sangha.[48]

The Kushan monk Lokakṣema began translating Pure Land Buddhist texts into Chinese in the century prior to Mani arriving there. The Chinese texts of Manichaeism are full of uniquely Buddhist terms taken directly from these Chinese Pure Land scriptures, including the term "pure land" (Chinese: 淨土; pinyin: jìngtǔ) itself.[49] However, the central object of veneration in Pure Land Buddhism, Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, does not appear in Chinese Manichaeism and seems to have been replaced by another deity.[50]

Spread

Roman Empire

Manichaeism reached Rome through the apostle Psattiq in 280, who was also in Egypt in 244 and 251. It flourished in the Faiyum in 290.

Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 during the time of Pope Miltiades.[51]

In 291, persecution arose in the Sasanian Empire with the murder of the apostle Sisin by Emperor Bahram II and the slaughter of many Manichaeans. Then, in 302, the first official reaction and legislation against Manichaeism from the Roman state was issued under Diocletian. In an official edict called the De Maleficiis et Manichaeis compiled in the Collatio Legum Mosaicarum et Romanarum and addressed to the proconsul of Africa, Diocletian wrote:

We have heard that the Manichaeans [...] have set up new and hitherto unheard-of sects in opposition to the older creeds so that they might cast out the doctrines vouchsafed to us in the past by the divine favour for the benefit of their own depraved doctrine. They have sprung forth very recently like new and unexpected monstrosities among the race of the Persians – a nation still hostile to us – and have made their way into our empire, where they are committing many outrages, disturbing the tranquility of our people and even inflicting grave damage to the civic communities. We have cause to fear that with the passage of time they will endeavour, as usually happens, to infect the modest and tranquil of an innocent nature with the damnable customs and perverse laws of the Persians as with the poison of a malignant (serpent) ... We order that the authors and leaders of these sects be subjected to severe punishment, and, together with their abominable writings, burnt in the flames. We direct their followers, if they continue recalcitrant, shall suffer capital punishment, and their goods be forfeited to the imperial treasury. And if those who have gone over to that hitherto unheard-of, scandalous and wholly infamous creed, or to that of the Persians, are persons who hold public office, or are of any rank or of superior social status, you will see to it that their estates are confiscated and the offenders sent to the (quarry) at Phaeno or the mines at Proconnesus. And in order that this plague of iniquity shall be completely extirpated from this our most happy age, let your devotion hasten to carry out our orders and commands.[52]

By 354, Hilary of Poitiers wrote that Manichaeism was a significant force in Roman Gaul. In 381, Christians requested Theodosius I to strip Manichaeans of their civil rights. Starting in 382, the emperor issued a series of edicts to suppress Manichaeism and punish its followers.[53]

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) converted to Christianity from Manichaeism in the year 387. This was shortly after the Roman emperor Theodosius I issued a decree of death for all Manichaean monks in 382 and shortly before he declared Christianity the only legitimate religion for the Roman Empire in 391. Due to the heavy persecution, the religion almost disappeared from Western Europe in the fifth century and from the eastern portion of the empire in the sixth century.[54]

According to his Confessions, after nine or ten years of adhering to the Manichaean faith as a member of the group of "hearers", Augustine of Hippo became a Christian and potent adversary of Manichaeism (which he expressed in writing against his Manichaean opponent Faustus of Mileve), seeing their beliefs that knowledge was the key to salvation as too passive and unable to affect any change in one's life.[55]

I still thought that it is not we who sin but some other nature that sins within us. It flattered my pride to think that I incurred no guilt and, when I did wrong, not to confess it ... I preferred to excuse myself and blame this unknown thing which was in me but was not part of me. The truth, of course, was that it was all my own self, and my own impiety had divided me against myself. My sin was all the more incurable because I did not think myself a sinner.[56]

Some modern scholars have suggested that Manichaean ways of thinking influenced the development of some of Augustine's ideas, such as the nature of good and evil, the idea of hell, the separation of groups into elect, hearers, and sinners, and the hostility to the flesh and sexual activity, and his dualistic theology.[57]

Central Asia

Some Sogdians in Central Asia believed in the religion.[58][59] Uyghur khagan Boku Tekin (759–780) converted to the religion in 763 after a three-day discussion with its preachers,[60][61] the Babylonian headquarters sent high-rank clerics to Uyghur, and Manichaeism remained the state religion for about a century before the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840.[citation needed]

China

In the east it spread along trade routes as far as Chang'an, the capital of Tang China.[62][63]

After the Tang dynasty, some Manichaean groups participated in peasant movements. Many rebel leaders used religion to mobilize followers. In Song and Yuan China, remnants of Manichaeism continued to leave a legacy contributing to sects such as the Red Turbans. During the Song dynasty, the Manichaeans were derogatorily referred by the Chinese as Chīcài shìmó (Chinese: 吃菜事魔, meaning that they "abstain from meat and worship demons").[64][65]

An account in Fozu Tongji, an important historiography of Buddhism in China compiled by Buddhist scholars during 1258–1269, says that the Manichaeans worshipped the "White Buddha" and their leader wore a violet headgear, while the followers wore white costumes. Many Manichaeans took part in rebellions against the Song government and were eventually quelled. After that, all governments were suppressive against Manichaeism and its followers, and the religion was banned in Ming China in 1370.[66][65] While it had long been thought that Manichaeism arrived in China only at the end of the seventh century, a recent[when?] archaeological discovery demonstrated that it was already known there in the second half of the 6th century.[67]

The nomadic Uyghur Khaganate lasted for less than a century (744–840) in the southern Siberian steppe, with the fortified city of Ordu-Baliq on the Upper Orkhon River as its capital.[68] Before the end of the year (763), Manichaeism was declared the official religion of the Uyghur state. Boku Tekin banned all the shamanistic rituals that had previously been in use. His subjects likely accepted his decision. That much results from a report that the proclamation of Manichaeism as the state religion was met with enthusiasm in Ordu-Baliq. In an inscription in which the Kaghan speaks for himself, he promised the Manichaen high priests (the "Elect") that if they gave orders, he would promptly follow them and respond to their requests. An incomplete manuscript found in the Turfan Oasis gives Boku Tekin the title of zahag-i Mani ("Emanation of Mani" or "Descendant of Mani"), a title of majestic prestige among the Manichaeans of Central Asia.

Nonetheless, and despite the apparently willing conversion of the Uyghurs to Manichaeanism, traces and signs of the previous shamanistic practices persisted. For instance, in 765, only two years after the official conversion, during a military campaign in China, the Uyghur troops called forth magicians to perform a number of specific rituals. Manichaean Uyghurs continued to treat with great respect a sacred forest in Otuken.[68] The conversion to Manichaeism led to an explosion of manuscript production in the Tarim Basin and Gansu (the region between the Tibetan and the Huangtu plateaus), which lasted well into the early 11th century. In 840, the Uyghur Khaganate collapsed under the attacks of the Yenisei Kyrgyz, and the new Uyghur state of Qocho was established with a capital in the city of Qocho.

Al-Jahiz (776–868 or 869) believed that the peaceful lifestyle that Manicheism brought to the Uyghurs was responsible for their later lack of military skills and eventual decline. This, however, is contradicted by the political and military consequences of the conversion. After the migration of the Uyghurs to Turfan in the ninth century, the nobility maintained Manichaean beliefs for a while before converting to Buddhism. Traces of Manicheism among the Uyghurs in Turfan may be detected in fragments of Uyghur Manichaean manuscripts. In fact, Manicheism continued to rival the influence of Buddhism among the Uyghurs until the 13th century. The Mongols gave the final blow to the Manichaeism among the Uyghurs.[68]

Tibet

Manichaeism spread to Tibet during the Tibetan Empire. There was a serious attempt made to introduce the religion to the Tibetans as the text Criteria of the Authentic Scriptures (a text attributed to the Tibetan Emperor Trisong Detsen) makes a great effort to attack Manichaeism by stating that Mani was a heretic who engaged in religious syncretism into a deviating and inauthentic form.[69]

Iran

Manichaeans in Iran tried to assimilate their religion along with Islam in the Muslim caliphates.[70] Relatively little is known about the religion during the first century of Islamic rule. During the early caliphates, Manichaeism attracted many followers. It had a significant appeal among Muslim society, especially among the elites. A part of Manichaeism that specifically appealed to the Sasanians was the Manichaean gods' names. The names Mani had assigned to the gods of his religion show identification with those of the Zoroastrian pantheon, even though some divine beings he incorporates are non-Iranian. For example, Jesus, Adam, and Eve were named Xradesahr, Gehmurd, and Murdiyanag. Because of these familiar names, Manichaeism did not feel completely foreign to the Zoroastrians.[71] Due to the appeal of its teachings, many Sasanians adopted the ideas of its theology and some even became dualists.

Not only were the citizens of the Sasanian Empire intrigued by Manichaeism, but so was the ruler at the time of its introduction, Sabuhr l. As the Denkard reports, Sabuhr, the first King of Kings, was very well-known for gaining and seeking knowledge of any kind. Because of this, Mani knew that Sabuhr would lend an ear to his teachings and accept him. Mani had explicitly stated while introducing his teachings to Sabuhr, that his religion should be seen as a reform of Zarathrusta's ancient teachings.[71] This was of great fascination to the king, for it perfectly fit Sabuhr's dream of creating a large empire that incorporated all people and their different creeds. Thus, Manichaeism became widespread and flourished throughout the Sasanian Empire for thirty years. An apologia for Manichaeism ascribed to ibn al-Muqaffa' defended its phantasmagorical cosmogony and attacked the fideism of Islam and other monotheistic religions. The Manichaeans had sufficient structure to have a head of their community.[72][73][74]

Tolerance toward Manichaeism decreased after the death of Sabuhr I. His son, Ohrmazd, who became king, still allowed for Manichaeism in the empire, but he also greatly trusted the Zoroastrian priest, Kirdir. After Ohrmazd's short reign, his oldest brother, Wahram I, became king. Wahram I held Kirdir in high esteem, and he also had many different religious ideals than Ohrmazd and his father, Sabuhr I. Due to the influence of Kirdir, Zoroastrianism was strengthened throughout the empire, which in turn caused Manichaeism to be diminished. Wahram sentenced Mani to prison, and he died there.[71]

Arab world

Under the eighth-century Abbasid Caliphate, Arabic zindīq and the adjectival term zandaqa could denote many different things, but it seems to have primarily—or at least initially—signified a follower of Manichaeism; however its true meaning is not known.[75] From the ninth century, it is reported that Caliph al-Ma'mun tolerated a community of Manichaeans.[76]

During the early Abbasid period, the Manichaeans underwent persecution. The third Abbasid caliph, al-Mahdi, persecuted the Manichaeans, establishing an inquisition against dualists who, if found guilty of heresy, refused to renounce their beliefs, were executed. Their persecution was ended in the 780s by Harun al-Rashid.[77][78] During the reign of the Caliph al-Muqtadir, many Manichaeans fled from Mesopotamia to Khorasan in fear of persecution, and the base of the religion was later shifted to Samarkand.[54][79]

Bactria

The first appearance of Manichaeism in Bactria was actually during Mani's lifetime. While he never physically traveled there, he did send a disciple by the name of Mar Ammo to spread his word. Mani "called (upon) Mar Ammo, the teacher, who knew the Parthian language and script, and was well acquainted with lords and ladies and with many nobles in those places..."[80]

Mar Ammo indeed did travel to the old Parthian lands of eastern Iran, which bordered Bactria. A translation of Persian texts states the following from the perspective of Mar Ammo: "They had arrived at the watch post of Kushān (Bactria), then the spirit of the border of the eastern province appeared in the shape of a girl, and he (the spirit) asked me 'Ammo what do you intend? From where have you come?' I said, 'I am a believer, a disciple of Mani, the Apostle.' That spirit said 'I do not receive you. Return from where you have come.'"

Despite the initial rejection Mar Ammo faced, the text records that Mani's spirit appeared to Mar Ammo and requested he persevere and read the chapter "The Collecting of the Gates" from The Treasure of the Living. Once he did so, the spirit returned, transformed, and said, "I am Bag Ard, the frontier guard of the Eastern Province. When I receive you, then the gate of the whole East will be opened in front of you." It seemed that this "border spirit" was a reference to the local Eastern Iranian goddess Ard-oxsho, who was prevalent in Bactria.[81]

Syncretism and translation

Manichaeism claimed to present the complete version of teachings that were corrupted and misinterpreted by the followers of Mani's predecessors Adam, Abraham, Noah,[9] Zoroaster, the Buddha, and Jesus.[82] Accordingly, as it spread, it adapted deities from other religions into forms it could use for its scriptures. Its original Eastern Middle Aramaic texts already contained stories of Jesus.

As the faith moved eastward and its scriptures were translated into Iranian languages, the names of the Manichaean deities were often transformed into the names of Zoroastrian yazatas. Thus, Abbā ḏəRabbūṯā ("The Father of Greatness"), the highest Manichaean deity of Light, in Middle Persian texts might either be translated literally as pīd ī wuzurgīh or substituted with the name of the deity Zurwān.

Similarly, the Manichaean primordial figure Nāšā Qaḏmāyā ("The Original Man") was rendered Ohrmazd Bay after the Zoroastrian god Ohrmazd. This process continued in Manichaeism's meeting with Chinese Buddhism, during which, for example, the original Aramaic קריא qaryā (the "call" from the World of Light to those seeking rescue from the World of Darkness) is identified in the Chinese-language scriptures with Guanyin (觀音 or Avalokiteśvara in Sanskrit, literally, "watching/perceiving sounds [of the world]", the bodhisattva of Compassion).[citation needed]

Manichaeism influenced some early texts and traditions of proto-orthodox and other forms of early Christianity, as well as doing the same for branches of Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam.[83]

Persecution and suppression

Manichaeism was repressed by the Sasanian Empire.[70] In 291, persecution arose in the Persian empire with the murder of the apostle Sisin by Bahram II and the slaughter of many Manichaeans. In 296, the Roman emperor Diocletian decreed all the Manichaean leaders to be burnt alive along with the Manichaean scriptures, and many Manichaeans in Europe and North Africa were killed. It was not until 372 with Valentinian I and Valens that Manichaeism was legislated against again.[84]

Theodosius I issued a death decree for all Manichaean monks in 382 CE.[85] The religion was vigorously attacked and persecuted by both the Christian Church and the Roman state, and the religion almost disappeared from western Europe in the fifth century and from the eastern portion of the empire in the sixth century.[54]

In 732, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang banned any Chinese from converting to the religion, saying it was a heretic religion, confusing people by claiming to be Buddhism. However, the foreigners who followed the religion were allowed to practice it without punishment.[87] After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840, which was the chief patron of Manichaeism (which was also the state religion of the Khaganate) in China, all Manichaean temples in China except in the two capitals and Taiyuan were closed down and never reopened since these temples were viewed as a symbol of foreign arrogance by the Chinese (see Cao'an). Even those that were allowed to remain open did not for long.[63]

The Manichaean temples were attacked by Chinese people who burned the images and idols of these temples. Manichaean priests were ordered to wear hanfu instead of traditional clothing, viewed as un-Chinese. In 843, Emperor Wuzong of Tang gave the order to kill all Manichaean clerics as part of the Huichang persecution of Buddhism, and over half died. They were made to look like Buddhists by the authorities; their heads were shaved, they were made to dress like Buddhist monks and then killed.[63]

Many Manichaeans took part in rebellions against the Song dynasty. They were quelled by Song China and were suppressed and persecuted by all successive governments before the Mongol Yuan dynasty. In 1370, the religion was banned through an edict of the Ming dynasty, whose Hongwu Emperor had a personal dislike for the religion.[63][65][88] Its core teaching influences many religious sects in China, including the White Lotus movement.[89]

According to Wendy Doniger, Manichaeism may have continued to exist in the Xinjiang region until the Mongol conquest in the 13th century.[90]

Manicheans also suffered persecution for some time under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad. In 780, the third Abbasid Caliph, al-Mahdi, started a campaign of inquisition against those who were "dualist heretics" or "Manichaeans" called the zindīq. He appointed a "master of the heretics" (Arabic: صاحب الزنادقة ṣāhib al-zanādiqa), an official whose task was to pursue and investigate suspected dualists, who the Caliph then examined. Those found guilty who refused to recant their beliefs were executed.[77]

This persecution continued under his successor, Caliph al-Hadi, and continued for some time during the reign of Harun al-Rashid, who finally abolished it and ended it.[77] During the reign of the 18th Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir, many Manichaeans fled from Mesopotamia to Khorasan from fear of persecution by him and about 500 of them assembled in Samarkand. The base of the religion was later shifted to this city, which became their new Patriarchate.[54][79]

Manichaean pamphlets were still in circulation in Greek in 9th-century Byzantine Constantinople, as the patriarch Photios summarizes and discusses one that he has read by Agapius in his Bibliotheca.

Later movements associated with Manichaeism

During the Middle Ages, several movements emerged that were collectively described as "Manichaean" by the Catholic Church and persecuted as Christian heresies through the establishment of the Inquisition in 1184.[91] They included the Cathar churches of Western Europe. Other groups sometimes referred to as "neo-Manichaean" were the Paulician movement, which arose in Armenia,[92] and the Bogomils in Bulgaria and Serbia.[93] An example of this usage can be found in the published edition of the Latin Cathar text, the Liber de duobus principiis (Book of the Two Principles), which was described as "Neo-Manichaean" by its publishers.[94] As there is no presence of Manichaean mythology or church terminology in the writings of these groups, there has been some dispute among historians as to whether these groups were descendants of Manichaeism.[95]

Manichaeism could have influenced the Bogomils, Paulicians, and Cathars. However, these groups left few records, and the link between them and Manichaeans is tenuous. Regardless of its accuracy, the charge of Manichaeism was leveled at them by contemporary orthodox opponents, who often tried to make contemporary heresies conform to those combatted by the church fathers.[93]

Whether the dualism of the Paulicians, Bogomils, and Cathars and their belief that the world was created by a Satanic demiurge was due to influence from Manichaeism is impossible to determine. The Cathars apparently adopted the Manichaean principles of church organization. Priscillian and his followers may also have been influenced by Manichaeism. The Manichaeans preserved many apocryphal Christian works, such as the Acts of Thomas, that would otherwise have been lost.[93]

Legacy in present-day

Some sites are preserved in Xinjiang, Zhejiang, and Fujian in China.[96][97] The Cao'an temple is the most widely known, and best preserved Manichaean building,[35]: 256–257 though it later became associated with Buddhism.[98] Other temples in China associated with Manichaeism also exist, such as the Xuanzhen Temple, noted for its stele.

Chinese Manichaeans continue to practice the faith, mainly in Fujian and Zhejiang.[99][100][101] Some platforms on the internet and social media are trying to spread some of its teachings. Some people are registered in these electronic sources, and some scholars and students in the field of religious studies and the arts continue to study Manichaeism.[102]

Teachings and beliefs

General

Mani's teaching dealt with the origin of evil by addressing a theoretical part of the problem of evil: denying the omnipotence of God and instead postulating two opposite divine powers. Manichaean theology teaches a dualistic view of good and evil. A fundamental belief in Manichaeism is that the powerful, though not omnipotent, good power (God) was opposed by the eternal evil power (the devil). Humanity, the world, and the soul are seen as the by-product of the battle between God's proxy—Primal Man—and the devil.[103]

The human person is seen as a battleground for these powers: the soul defines the person but is influenced by light and dark. This contention plays out over the world and the human body—neither the Earth nor the flesh were seen as intrinsically evil but instead possessed both light and dark portions. Natural phenomena such as rain were seen as the physical manifestation of this spiritual contention. Therefore, the Manichaean view explained the existence of evil by positing a flawed creation in the formation of which God took no part and which constituted instead the product of a battle by the devil against God.[103]

Cosmogony

Manichaeism presents an elaborate conflict between the spiritual world of light and the material world of darkness. The beings of both the world of darkness and the world of light have names. There are numerous sources for the details of the Manichaean belief[example needed]. These[specify] two portions of the scriptures are probably the closest thing to the original writings in their original languages that will ever be available. These are the Syriac quotation by the Church of the East Christian Theodore bar Konai in his 8th century Syriac scholion, the Ketba de-Skolion,[46] and the Middle Persian sections of Mani's Shabuhragan discovered at Turpan—a summary of Mani's teachings prepared for Shapur I.[24]

From these and other sources[example needed], it is possible to derive a near-complete description of the detailed Manichaean cosmogony.[104] (A complete list of Manichaean deities is outlined below.) According to Mani,[citation needed]the unfolding of the universe took place in three phases:

- The First Creation

- Originally, good and evil existed in two completely separate realms: one the World of Light (Chinese: 明界), ruled by the Father of Greatness together with his five Shekhinas (i.e., divine attributes of light), and the other the World of Darkness ruled by the King of Darkness. At a point in the distant past, the Kingdom of Darkness noticed the World of Light, coveted it, and attacked it. The Father of Greatness, in the first of three "calls" or "creations", called to the Mother of Life who sent her son, Original Man (Imperial Aramaic: Nāšā Qaḏmāyā), to battle with the attacking powers of Darkness, which included the Demon of Greed.

The Original Man was armed with five different shields of light (reflections of the five Shekhinahs), which he lost to the forces of Darkness in the ensuing battle—described as a kind of "bait" to trick the forces of Darkness, who greedily consume as much light as they can. When the Original Man awakened, he was trapped among the forces of Darkness.

- The Second Creation

- Then, the Father of Greatness began the Second Creation. He called to the Living Spirit[specify], who then called to his sons and the Original Man, after which Call became a Manichaean deity proper. An answer—Answer became another Manichaean deity—then went out from the Original Man to the World of Light. Then, the Mother of Life, the Living Spirit, and his five sons began to create the universe from the bodies of the evil beings of the World of Darkness, together with the light they had swallowed. Ten heavens and eight earths were created, all consisting of various mixtures of the evil material beings from the World of Darkness and the swallowed light. The sun, moon, and stars were all created from light recovered from the World of Darkness. The waxing and waning of the moon are described as the "moon filling with light", which passed to the sun, then through the Milky Way, and eventually back to the World of Light.

- The Third Creation

- Great demons (called archons in bar-Konai's account) were hung over the heavens, and the Father of Greatness began the Third Creation. The light was recovered from the material bodies of the male and female evil beings and demons by causing them to become sexually aroused in greed toward beautiful images of the beings of light, such as the Third Messenger and the Virgins of Light. However, as soon as the light was expelled from their bodies and fell to the earth (some in the form of abortions—the source of fallen angels in the Manichaean myth), the evil beings continued to swallow up as much of it as they could to keep the light inside themselves. This resulted eventually in the evil beings swallowing vast quantities of light, copulating, and producing Adam and Eve. The Father of Greatness then sent Jesus the Splendour to awaken Adam and enlighten him to the true source of the light trapped in his material body. Adam and Eve, however, eventually copulated and produced more human beings, trapping the light in the bodies of humankind throughout human history. The appearance of the Prophet Mani was another attempt by the World of Light to reveal to humanity the true source of the spiritual light imprisoned within their material bodies.

- Analysis of Mani's cosmology as illustrated in the Manichaean Diagram

- Heaven scene from the Manichaean Diagram

- "Maiden of Light" from the Manichaean Diagram

Cosmology

In the sixth century, many Manichaeans saw "the earth" as "a rectangular parallelepiped enclosed by walls of crystal, above which three [sky] domes" existed, with the other two being above and larger than the first one and second one, respectively.[105] These represented the "three heavens" in Chaldean religion.[105]

Outline of the beings and events in the Manichaean mythology

Beginning with the time of its creation by Mani, the Manichaean religion has had a detailed description of deities and events that took place within the Manichaean scheme of the universe. In every language and region that Manichaeism spread to, these same deities reappear, whether it is in the original Syriac quoted by Theodore bar Konai,[46] or the Latin terminology given by Saint Augustine from Mani's Epistola Fundamenti, or the Persian and Chinese translations found as Manichaeism spread eastward. While the original Syriac retained the original description that Mani created, the transformation of the deities through other languages and cultures produced incarnations of the gods not implied in the original Syriac writings. Chinese translations are especially syncretic, borrowing and adapting terminology common in Chinese Buddhism.[106]

The Manichaean Church

Organization

The Manichaean Church was divided into the Elect, who had taken upon themselves the vows of Manichaeism, and the Hearers, those who had not, but still participated in the Church. The Elect were forbidden to consume alcohol and meat, as well as to harvest crops or prepare food, due to Mani's claim that harvesting was a form of murder against plants. The Hearers would therefore commit the sin of preparing food, and would provide it to the Elect, who would in turn pray for the Hearers and cleanse them of these sins.[107]

The terms for these divisions were already common since the days of early Christianity, however, it had a different meaning in Christianity. In Chinese writings, the Middle Persian and Parthian terms are transcribed phonetically (instead of being translated into Chinese).[108] These were recorded by Augustine of Hippo.[14]

- The Leader (Syriac: ܟܗܢܐ /kɑhnɑ/; Parthian: yamag; Chinese: 閻默; pinyin: yánmò), Mani's designated successor, seated as Patriarch at the head of the Church, originally in Ctesiphon, from the ninth century in Samarkand. Two notable leaders were Mār Sīsin (or Sisinnios), the first successor of Mani, and Abū Hilāl al-Dayhūri, an eighth-century leader.

- 12 Apostles (Latin: magistrī; Syriac: ܫܠܝܚܐ /ʃ(ə)liħe/; Middle Persian: možag; Chinese: 慕闍; pinyin: mùdū). Three of Mani's original apostles were Mār Pattī (Pattikios; Mani's father), Akouas and Mar Ammo.

- 72 Bishops (Latin: episcopī; Syriac: ܐܦܣܩܘܦܐ /ʔappisqoppe/; Middle Persian: aspasag, aftadan; Chinese: 薩波塞; pinyin: sàbōsāi or Chinese: 拂多誕; pinyin: fúduōdàn; see also: seventy disciples). One of Mani's original disciples who was specifically referred to as a bishop was Mār Addā.

- 360 Presbyters (Latin: presbyterī; Syriac: ܩܫܝܫܐ /qaʃʃiʃe/; Middle Persian: mahistan; Chinese: 默奚悉德; pinyin: mòxīxīdé)

- The general body of the Elect (Latin: ēlēctī; Syriac: ܡܫܡܫܢܐ /m(ə)ʃamməʃɑne/; Middle Persian: ardawan or dēnāwar; Chinese: 阿羅緩; pinyin: āluóhuǎn or Chinese: 電那勿; pinyin: diànnàwù)

- The Hearers (Latin: audītōrēs; Syriac: ܫܡܘܥܐ /ʃɑmoʿe/; Middle Persian: niyoshagan; Chinese: 耨沙喭; pinyin: nòushāyàn)

Religious practices

Prayers

From Manichaean sources, Manichaeans observed daily prayers: four for the hearers or seven for the elect. The sources differ about the exact time of prayer. The Fihrist by al-Nadim appoints them afternoon, mid-afternoon, just after sunset, and at nightfall. Al-Biruni places the prayers at dawn, sunrise, noon, and dusk. The elect additionally prayed at mid-afternoon, half an hour after nightfall, and midnight. Al-Nadim's account of daily prayers is probably adjusted to coincide with the public prayers for the Muslims, while Al-Biruni's report may reflect an older tradition unaffected by Islam.[109][110]

When Al-Nadim's account of daily prayers was the only detailed source available, there was a concern that Muslims only adopted these practices during the Abbasid Caliphate. However, it is clear that the Arabic text provided by Al-Nadim corresponds with the descriptions of Egyptian texts from the fourth century.[111]

Every prayer started with an ablution with water or, if water was not available, with other substances comparable to ablution in Islam,[112] and consisted of several blessings to the apostles and spirits. The prayer consisted of prostrating oneself to the ground and rising again twelve times during every prayer.[113] During the day, Manichaeans turned towards the Sun and during the night towards the Moon. If the Moon is not visible at night, they turned towards the north.[114]

Evident from Faustus of Mileve, Celestial bodies are not the subject of worship themselves but are "ships" carrying the light particles of the world to the supreme god, who cannot be seen, since he exists beyond time and space, and also the dwelling places for emanations of the supreme deity, such as Jesus the Splendour.[114] According to the writings of Augustine of Hippo, ten prayers were performed, the first devoted to the Father of Greatness, and the following to lesser deities, spirits, and angels and finally towards the elect, to be freed from rebirth and pain and to attain peace in the realm of light.[111] Comparably, in the Uyghur confession, four prayers are directed to the supreme God (Äzrua), the God of the Sun and the Moon, and fivefold God and the buddhas.[114]

Primary sources

Mani wrote seven books, which contained the teachings of the religion. Only scattered fragments and translations of the originals remain, most having been discovered in Egypt and Turkistan during the 20th century.[33]

The original six Syriac writings are not preserved, although their Syriac names have been. There are also fragments and quotations from them. A long quotation, preserved by the eighth-century Nestorian Christian author Theodore Bar Konai,[46] shows that in the original Syriac Aramaic writings of Mani there was no influence of Iranian or Zoroastrian terms. The terms for the Manichaean deities in the original Syriac writings are in Aramaic. The adaptation of Manichaeism to the Zoroastrian religion appears to have begun in Mani's lifetime however, with his writing of the Middle Persian Shabuhragan, his book dedicated to the Sasanian emperor, Shapur I.[24]

In it, there are mentions of Zoroastrian divinities such as Ahura Mazda, Angra Mainyu, and Āz. Manichaeism is often presented as a Persian religion, mostly due to the vast number of Middle Persian, Parthian, and Sogdian (as well as Turkish) texts discovered by German researchers near Turpan in what is now Xinjiang, China, during the early 1900s. However, from the vantage point of its original Syriac descriptions (as quoted by Theodore Bar Khonai and outlined above), Manichaeism may be better described as a unique phenomenon of Aramaic Babylonia, occurring in proximity to two other new Aramaic religious phenomena, Talmudic Judaism and Mandaeism, which also appeared in Babylonia in roughly the third century.[citation needed]

The original, but now lost, six sacred books of Manichaeism were composed in Syriac Aramaic, and translated into other languages to help spread the religion. As they spread to the east, the Manichaean writings passed through Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian, Tocharian, and ultimately Uyghur and Chinese translations. As they spread to the west, they were translated into Greek, Coptic, and Latin. Most Manichaean texts survived only as Coptic and Medieval Chinese translations of their original, lost versions.[115]

Henning describes how this translation process evolved and influenced the Manichaeans of Central Asia:

Beyond doubt, Sogdian was the national language of the Majority of clerics and propagandists of the Manichaean faith in Central Asia. Middle Persian (Pārsīg), and to a lesser degree, Parthian (Pahlavānīg), occupied the position held by Latin in the medieval church. The founder of Manichaeism had employed Syriac (his own language) as his medium, but conveniently he had written at least one book in Middle Persian, and it is likely that he himself had arranged for the translation of some or all of his numerous writings from Syriac into Middle Persian. Thus the Eastern Manichaeans found themselves entitled to dispense with the study of Mani's original writings, and to continue themselves to reading the Middle Persian edition; it presented small difficulty to them to acquire a good knowledge of the Middle Persian language, owing to its affinity with Sogdian.[118]

Originally written in Syriac

- the Gospel of Mani (Syriac: ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ /ʔɛwwanɡallijon/; Koinē Greek: εὐαγγέλιον "good news, gospel"). Quotations from the first chapter were brought in Arabic by ibn al-Nadim, who lived in Baghdad at a time when there were still Manichaeans living there, in his 938 book, the Fihrist, a catalog of all written books known to him.

- The Treasure of Life

- The Treatise (Coptic: πραγματεία, pragmateia)

- Secrets

- The Book of Giants: Original fragments were discovered at Qumran (pre-Manichaean) and Turpan.

- Epistles: Augustine brings quotations, in Latin, from Mani's Fundamental Epistle in some of his anti-Manichaean works.

- Psalms and Prayers: A Coptic Manichaean Psalm Book, discovered in Egypt in the early 1900s, was edited and published by Charles Allberry from Manichaean manuscripts in the Chester Beatty collection and in the Berlin Academy, 1938–39.

Originally written in Middle Persian

- The Shabuhragan, dedicated to Shapur I: Original Middle Persian fragments were discovered at Turpan, quotations were brought in Arabic by al-Biruni.

Other books

- The Ardahang, the "Picture Book". In Iranian tradition, this was one of Mani's holy books that became remembered in later Persian history, and was also called Aržang, a Parthian word meaning "Worthy", and was beautified with paintings. Therefore, Iranians gave him the title of "The Painter".

- The Kephalaia of the Teacher (Κεφαλαια), "Discourses", found in Coptic translation.

- On the Origin of His Body, the title of the Cologne Mani-Codex, a Greek translation of an Aramaic book that describes the early life of Mani.[22]

Non-Manichaean works preserved by the Manichaean Church

- Portions of the Book of Enoch literature such as the Book of Giants

- Literature relating to the apostle Thomas (who by tradition went to India, and was also venerated in Syria), such as portions of the Syriac The Acts of Thomas, and the Psalms of Thomas. The Gospel of Thomas was also attributed to Manichaeans by Cyril of Jerusalem, a fourth-century Church Father.[119]

- The legend of Barlaam and Josaphat passed from an Indian story about the Buddha, through a Manichaean version, before it transformed into the story of a Christian Saint in the west.

Later works

In later centuries, as Manichaeism passed through eastern Persian-speaking lands and arrived at the Uyghur Khaganate (回鶻帝國), and eventually the Uyghur kingdom of Turpan (destroyed around 1335), Middle Persian and Parthian prayers (āfrīwan or āfurišn) and the Parthian hymn-cycles (the Huwīdagmān and Angad Rōšnan created by Mar Ammo) were added to the Manichaean writings.[120] A translation of a collection of these produced the Manichaean Chinese Hymnscroll (Chinese: 摩尼教下部讚; pinyin: Móní-jiào Xiàbù Zàn, which Lieu translates as "Hymns for the Lower Section [i.e. the Hearers] of the Manichaean Religion"[121]).

In addition to containing hymns attributed to Mani, it contains prayers attributed to Mani's earliest disciples, including Mār Zaku, Mār Ammo and Mār Sīsin. Another Chinese work is a complete translation of the Sermon of the Light Nous, presented as a discussion between Mani and his disciple Adda.[122]

Critical and polemic sources

Until discoveries in the 1900s of original sources, the only sources for Manichaeism were descriptions and quotations from non-Manichaean authors, either Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, or Zoroastrian ones. While often criticizing Manichaeism, they also quoted directly from Manichaean scriptures. This enabled Isaac de Beausobre, writing in the 18th century, to create a comprehensive work on Manichaeism, relying solely on anti-Manichaean sources.[123][124] Thus quotations and descriptions in Greek and Arabic have long been known to scholars, as have the long quotations in Latin by Saint Augustine, and the extremely important quotation in Syriac by Theodore Bar Konai.[citation needed]

Patristic depictions of Mani and Manichaeism

Eusebius commented as follows:

The error of the Manichees, which commenced at this time.

— In the mean time, also, that madman Manes, (Mani is of Persian or Semitic origin) as he was called, well agreeing with his name, for his demoniacal heresy, armed himself by the perversion of his reason, and at the instruction of Satan, to the destruction of many. He was a barbarian in his life, both in speech and conduct, but in his nature as one possessed and insane. Accordingly, he attempted to form himself into a Christ, and then also proclaimed himself to be the very paraclete and the Holy Spirit, and with all this was greatly puffed up with his madness. Then, as if he were Christ, he selected twelve disciples, the partners of his new religion, and after patching together false and ungodly doctrines, collected from a thousand heresies long since extinct, he swept them off like a deadly poison, from Persia, upon this part of the world. Hence the impious name of the Manichaeans spreading among many, even to the present day. Such then was the occasion of this knowledge, as it was falsely called, that sprouted up in these times.[125]

Acta Archelai

An example of how inaccurate some of these accounts could be can be seen in the account of the origins of Manichaeism contained in the Acta Archelai. This was a Greek anti-Manichaean work written before 348, most well known in its Latin version, which was regarded as an accurate account of Manichaeism until refuted by Isaac de Beausobre in the 18th century:

In the time of the Apostles there lived a man named Scythianus, who is described as coming "from Scythia", and also as being "a Saracen by race" ("ex genere Saracenorum"). He settled in Egypt, where he became acquainted with "the wisdom of the Egyptians", and invented the religious system that was afterwards known as Manichaeism. Finally he emigrated to Palestine, and, when he died, his writings passed into the hands of his sole disciple, a certain Terebinthus. The latter betook himself to Babylonia, assumed the name of Budda, and endeavoured to propagate his master's teaching. But he, like Scythianus, gained only one disciple, who was an old woman. After a while he died, in consequence of a fall from the roof of a house, and the books that he had inherited from Scythianus became the property of the old woman, who, on her death, bequeathed them to a young man named Corbicius, who had been her slave. Corbicius thereupon changed his name to Manes, studied the writings of Scythianus, and began to teach the doctrines that they contained, with many additions of his own. He gained three disciples, named Thomas, Addas, and Hermas. About this time the son of the Persian king fell ill, and Manes undertook to cure him; the prince, however, died, whereupon Manes was thrown into prison. He succeeded in escaping, but eventually fell into the hands of the king, by whose order he was flayed, and his corpse was hung up at the city gate.

A. A. Bevan, who quoted this story, commented that it "has no claim to be considered historical".[126]

View of Judaism in the Acta Archelai

According to Hegemonius' portrayal of Mani, the evil demiurge who created the world was the Jewish Yahweh. Hegemonius reports that Mani said,

"It is the Prince of Darkness who spoke with Moses, the Jews and their priests. Thus the Christians, the Jews, and the Pagans are involved in the same error when they worship this God. For he leads them astray in the lusts he taught them." He goes on to state: "Now, he who spoke with Moses, the Jews, and the priests he says is the archont of Darkness, and the Christians, Jews, and pagans (ethnic) are one and the same, as they revere the same god. For in his aspirations he seduces them, as he is not the god of truth. And so therefore all those who put their hope in the god who spoke with Moses and the prophets have (this in store for themselves, namely) to be bound with him, because they did not put their hope in the god of truth. For that one spoke with them (only) according to their own aspirations.[127]

Central Asian and Iranian primary sources

In the early 1900s, original Manichaean writings started to come to light when German scholars led by Albert Grünwedel, and then by Albert von Le Coq, began excavating at Gaochang, the ancient site of the Manichaean Uyghur Kingdom near Turpan, in Chinese Turkestan (destroyed around 1300 CE). While most of the writings they uncovered were in very poor condition, there were still hundreds of pages of Manichaean scriptures, written in three Iranian languages (Middle Persian, Parthian, and Sogdian) and old Uyghur. These writings were taken back to Germany and were analyzed and published at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, by Le Coq and others, such as Friedrich W. K. Müller and Walter Bruno Henning. While the vast majority of these writings were written in a version of the Syriac script known as Manichaean script, the German researchers, perhaps for lack of suitable fonts, published most of them using the Hebrew alphabet (which could easily be substituted for the 22 Syriac letters).[citation needed]

Perhaps the most comprehensive of these publications was Manichaeische Dogmatik aus chinesischen und iranischen Texten (Manichaean Dogma from Chinese and Iranian texts), by Ernst Waldschmidt and Wolfgang Lentz, published in Berlin in 1933.[128] More than any other research work published before or since, this work printed, and then discussed, the original key Manichaean texts in the original scripts, and consists chiefly of sections from Chinese texts, and Middle Persian and Parthian texts transcribed with the Hebrew alphabet. After the Nazi Party gained power in Germany, the Manichaean writings continued to be published during the 1930s, but the publishers no longer used Hebrew letters, instead transliterating the texts into Latin letters.[citation needed]

Coptic primary sources

Additionally, in 1930, German researchers in Egypt found a large body of Manichaean works in Coptic. Though these were also damaged, hundreds of complete pages survived and, beginning in 1933, were analyzed and published in Berlin before World War II, by German scholars such as Hans Jakob Polotsky.[129] Some of these Coptic Manichaean writings were lost during the war.[130]

Chinese primary sources

After the success of the German researchers, French scholars visited China and discovered what is perhaps the most complete set of Manichaean writings, written in Chinese. These three Chinese writings, all found at the Mogao Caves among the Dunhuang manuscripts, and all written before the 9th century, are today kept in London, Paris, and Beijing. Some of the scholars involved with their initial discovery and publication were Édouard Chavannes, Paul Pelliot, and Aurel Stein. The original studies and analyses of these writings, along with their translations, first appeared in French, English, and German, before and after World War II. The complete Chinese texts themselves were first published in Tokyo, Japan in 1927, in the Taishō Tripiṭaka, volume 54. While in the last thirty years or so they have been republished in both Germany (with a complete translation into German, alongside the 1927 Japanese edition),[131] and China, the Japanese publication remains the standard reference for the Chinese texts.[citation needed]

Greek life of Mani, Cologne codex

In Egypt, a small codex was found and became known through antique dealers in Cairo. It was purchased by the University of Cologne in 1969. Two of its scientists, Henrichs and Koenen, produced the first edition known since as the Cologne Mani-Codex, which was published in four articles in the Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. The ancient papyrus manuscript contained a Greek text describing the life of Mani. Thanks to this discovery, much more is known about the man who founded one of the most influential world religions of the past.[132]

Figurative use

The terms "Manichaean" and "Manichaeism" are sometimes used figuratively as a synonym of the more general term "dualist" with respect to a philosophy, outlook, or world-view.[133] The terms are often used to suggest that the worldview in question simplistically reduces historical events to a struggle between good and evil. For example, Zbigniew Brzezinski used the phrase "Manichaean paranoia" in reference to U.S. president George W. Bush's worldview (in The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, 14 March 2007); Brzezinski elaborated that he meant "the notion that he [Bush] is leading the forces of good against the 'Axis of evil.'" Author and journalist Glenn Greenwald followed up on the theme in describing Bush in his book A Tragic Legacy (2007).

The term is frequently used by critics to describe the attitudes and foreign policies of the United States and its leaders.[134][135][136]

Philosopher Frantz Fanon frequently invoked the concept of Manicheanism in his discussions of violence between colonizers and the colonized.[137]

In My Secret History, author Paul Theroux's protagonist defines the word Manichaean for the protagonist's son as "seeing that good and evil are mingled." Before explaining the word to his son, the protagonist mentions Joseph Conrad's short story "The Secret Sharer" at least twice in the book, the plot of which also examines the idea of the duality of good and evil.[138]

See also

|

- Manichaean art

- Athinganoi, a purportedly related movement

- Abū Hilāl al-Dayhūri (8th century)

- Agapius (Manichaean) (4th or 5th century)

- Akouas

- Ancient Mesopotamian religion

- The Buddha in Manichaeism

- Chinese Manichaeism

- Good and evil

- Dualism in cosmology

- Hiwi al-Balkhi

- Indo-Iranian religion

- Jesus in Manichaeism

- Mar Ammo (3rd century)

- Mazdak

- Ming Cult

- Moral realism

- Abu Isa al-Warraq

- Yazdânism

- Yazidi

- Zurvanism

Notes

- ^ "According to the Fehrest, Mani was of Arsacid stock on both his father's and his mother's sides, at least if the readings al-ḥaskāniya (Mani's father) and al-asʿāniya (Mani's mother) are corrected to al-aškāniya and al-ašḡāniya (ed. Flügel, 1862, p. 49, ll. 2 and 3) respectively. The forefathers of Mani's father are said to have been from Hamadan and so perhaps of Iranian origin (ed. Flügel, 1862, p. 49, 5–6). The Chinese Compendium, which makes the father a local king, maintains that his mother was from the house Jinsajian, explained by Henning as the Armenian Arsacid family of Kamsarakan (Henning, 1943, p. 52, n. 4 1977, II, p. 115). Is that fact, or fiction, or both? The historicity of this tradition is assumed by most, but the possibility that Mani's noble Arsacid background is legendary cannot be ruled out (cf. Scheftelowitz, 1933, pp. 403–4). In any case, it is characteristic that Mani took pride in his origin from time-honored Babel, but never claimed affiliation to the Iranian upper class." – "Manichaeism" at Encyclopædia Iranica

References

- ^ a b Grenet, Frantz (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 93. ISBN 978-84-125278-5-8.

- ^ "Believers, Proselytizers, & Translators The Sogdians". sogdians.si.edu. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ GULÁCSI, ZSUZSANNA (2010). "The Prophet's Seal: A Contextualized Look at the Crystal Sealstone of Mani (216–276 C.E.) in the Bibliothèque nationale de France" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 24: 164. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 43896125.

- ^ "manichaeism". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern TimesSUNY Press, 1998 ISBN 978-0-7914-3611-0 p. 37

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3 (2), The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983.

- ^ "Manichaeism". New Advent Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Manichaeism" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ a b c Turner, Alice K. (1993). The History of Hell (1st ed.). United States: Harcourt Brace. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-15-140934-1.

- ^ Corrigan, Kevin; Rasimus, Tuomas (2013). Gnosticism, Platonism and the late ancient world: essays in honour of John D. Turner. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean studies. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22383-7.

- ^ Dardagan, Amer (13 May 2017). "Neoplatonism, The Response on Gnostic and Manichean ctiticism of Platonism". doi:10.31235/osf.io/krj2n. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Widengren, Geo Mesopotamian elements in Manichaeism (King and Saviour II): Studies in Manichaean, Mandaean, and Syrian-gnostic religion, Lundequistska bokhandeln, 1946.

- ^ Hopkins, Keith (July 2001). A World Full of Gods: The Strange Triumph of Christianity. New York: Plume. pp. 246, 263, 270. ISBN 0-452-28261-6. OCLC 47286228.

- ^ a b Arendzen, John (1 October 1910). "Manichæism Archived 1 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: The Encyclopedia Press, Inc.

- ^ Jason BeDuhn; Paul Allan Mirecki (2007). Frontiers of Faith: The Christian Encounter With Manichaeism in the Acts of Archelaus. BRILL. p. 6. ISBN 978-90-04-16180-1.

- ^ Andrew Welburn, Mani, the Angel and the Column of Glory: An Anthology of Manichaean Texts (Edinburgh: Floris Books, 1998), p. 68

- ^ Clarence, Siut Wai Hung. "The Forgotten Buddha: Manichaeism and Buddhist Elements in Imperial China". Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Gardner, Iain; Lieu, Samuel N. C., eds. (2004). Manichaean Texts from the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Definition of MANICHAEAN". merriam-webster.com. 15 July 2023. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Mary Boyce, Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices, Routledge, 2001. p. 111: "He was Iranian, of noble Parthian blood ..."

- ^ Warwick Ball, Rome in the East: the transformation of an empire, Routledge, 2001. p. 437: "Manichaeism was a syncretic religion, proclaimed by the Iranian Prophet Mani ...

- ^ a b L. Koenen and C. Römer, eds., Der Kölner Mani-Kodex. Über das Werden seines Leibes. Kritische Edition, (Abhandlung der Reinisch-Westfälischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Papyrologica Coloniensia 14) (Opladen, Germany) 1988.

- ^ Sundermann, Werner (20 July 2009). "MANI". Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Middle Persian Sources: D. N. MacKenzie, Mani's Šābuhragān, pt. 1 (text and translation), BSOAS 42/3, 1979, pp. 500–34, pt. 2 (glossary and plates), BSOAS 43/2, 1980, pp. 288–310.

- ^ Welburn (1998), pp. 67–68

- ^ Tardieu, Michel (2008). Manichaeism. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03278-3.

- ^ Joosten, Jan (1996). The Syriac Language of the Peshitta and Old Syriac Versions of Matthew: Syntactic Structure, Inner-Syriac Developments and Translation Technique. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10036-7.

- ^ a b Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Translated by Harari, Yuval Noah; Purcell, John; Watzman, Haim. London: Penguin Random House UK. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-09-959008-8. OCLC 910498369.

- ^ Reeves, John C. (1996). Heralds of That Good Realm: Syro-Mesopotamian Gnosis and Jewish Traditions. BRILL. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-90-04-10459-4. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ "Jainism – Posadha". Buddhism and Jainism. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. 2017. p. 585. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0852-2_100387. ISBN 978-94-024-0851-5.

- ^ Fynes, Richard C.C. (1996). "Plant Souls in Jainism and Manichaeism The Case for Cultural Transmission". East and West. 46 (1/2). Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO): 21–44. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757253. Archived from the original on 30 May 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ Coyle, John Kevin (2009). Manichaeism and Its Legacy. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. p. 7. ISBN 978-90-04-17574-7. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Manichaeism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ van Oort, Johannes (2020). "The Paraclete Mani as the Apostle of Jesus Christ and the Origins of a New Church". Mani and Augustine. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill.

- ^ a b Samuel N. C. Lieu (1992). Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China. J.C.B. Mohr. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-3-16-145820-0. OCLC 1100183055. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Saint Augustine (2006). Boniface Ramsey (ed.). The Manichean Debate, Volume 1; Volume 19. New City Press. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-1-56548-247-0. OCLC 552327717. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Manichaeism" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Stroumsa, Guy G. (2015). The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 95.

- ^ C. Colpe, "Das Siegel der Propheten: historische Beziehungen zwischen Judentum, Judenchristentum, Heidentum und frühem Islam", Arbeiten zur neutestamentlichen Theologie und Zeitgeschichte, 3 (Berlin: Institut Kirche und Judentum, 1990), 227–243.

- ^ G. G. Stroumsa, The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity, Oxford Studies in the Abrahamic Religions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 68.

- ^ "The Dead Sea Scrolls – 1Q Enoch, Book of Giants". The Dead Sea Scrolls – 1Q Enoch, Book of Giants. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ J. T. Milik, ed. and trans., The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976.

- ^ a b In: Henning, W. B., The Book of Giants, BSOAS, Vol. XI, Part 1, 1943, pp. 52–74.

- ^ Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions (1992)

- ^ See Henning, A Sogdian Fragment of the Manichaean Cosmogony, BSOAS, 1948

- ^ a b c d Original Syriac in: Theodorus bar Konai, Liber Scholiorum, II, ed. A. Scher, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium scrip. syri, 1912, pp. 311–8, ISBN 978-90-429-0104-9; English translation in: A.V.W. Jackson, Researches in Manichaeism, New York, 1932, pp. 222–54.

- ^ Ephraim, Saint; Press, Aeterna. Of Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan. Aeterna Press.

- ^ Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010, p. 71 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- ^ Peter Bryder, The Chinese Transformation of Manichaeism: A Study of Chinese Manichaean Terminology, 1985.

- ^ Lieu, Samuel N. C. (1998). Manichaeism in Central Asia and China. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10405-1.

- ^ Lieu, Samuel N. C. (1985). Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1088-0.

- ^ Iain Gardner and Samuel N. C. Lieu, eds., Manichaean Texts from the Roman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 117–18.

- ^ Lieu, Samuel (1992) Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China 2d edition, pp. 145–148

- ^ a b c d Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. pp. 689, 690. ISBN 978-90-6831-002-3.

- ^ "St. Augustine of Hippo". Catholic.org. Catholic Online. Archived from the original on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Confessions, Book V, Section 10.

- ^ A. Adam, Das Fortwirken des Manichäismus bei Augustin. In: ZKG (69) 1958, S. 1–25.

- ^ 从信仰摩尼教看漠北回纥[permanent dead link]

- ^ "关于回鹘摩尼教史的几个问题". Archived from the original on 7 August 2007.

- ^ "九姓回鹘爱登里罗汨没蜜施合毗伽可汗圣文神武碑". Bbs.sjtu.edu.cn. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ TM276 Uygurca_Alttuerkisch_Qedimi Uygurche/TT 2.pdf Türkische Turfan-Texte. ~[permanent dead link]

- ^ Perkins, Dorothy (2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7.

- ^ a b c d Samuel N. C. Lieu (1998). Manachaeism in Central Asia and China. Brill Publishers. pp. 115, 129, 130. ISBN 978-90-04-10405-1.

- ^ Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall (2013). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-285-54623-0.

- ^ a b c Xisha Ma, Huiying Meng (2011). Popular Religion and Shamanism. Brill Publishers. pp. 56, 57, 99. ISBN 978-90-04-17455-9.

- ^ Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall (2013). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-285-54623-0.

- ^ Étienne de la Vaissière, "Mani en Chine au VIe siècle", Journal asiatique, 293–1 (2005): 357–378.

- ^ a b c Hajianfard, Ramin (2016). Boku Tekin and the Uyghur Conversion to Manichaeism (763). Santa Barbara: CA, ABC-CLIO. pp. 409, 411. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4.

- ^ Schaeffer, Kurtis; Kapstein, Matthew; Tuttle, Gray (2013). Sources of Tibetan Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 95, 96. ISBN 978-0-231-13599-3.

- ^ a b Rippin, Andrew (2013). The Islamic World. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-136-80343-7.

- ^ a b c Hutter, Manfred (1993). "Manichaeism in the Early Sasanian Empire". Numen. 40 (1): 2–15. doi:10.2307/3270395. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3270395.

- ^ Berkey, Jonathan Porter (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99, 100. ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (2009). The Middle East. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-9000-5.

- ^ Lambton, Ann K. S. (2013). State and Government in Medieval Islam. Routledge. pp. 50, 51. ISBN 978-1-136-60521-5.

- ^ Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (1997), Religion and Politics Under the Early 'Abbasids: The Emergence of the Proto-Sunni Elite, Brill, pp. 63–65, ISBN 978-90-04-10678-9

- ^ Ibrahim, Mahmood (1994). "Religious inquisition as social policy: the persecution of the 'Zanadiqa' in the early Abbasid Caliphate". Arab Studies Quarterly. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Ames, Christine Caldwell (2015). Medieval Heresies. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-107-02336-9.

- ^ Irfan Shahîd, Byzantium and the Arabs in the fourth century, 1984, p. 425.

- ^ a b Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques; Lecoq, Pierre (1985). Papers in Honor of Professor Mary Boyce. Brill Publishers. p. 658. ISBN 978-90-6831-002-3.

- ^ Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (1993). Gnosis on the Silk Road: Gnostic texts from Central Asia (1st ed.). San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-064586-5. OCLC 28067600.

- ^ Scott, David (2007). "Manichaeism in Bactria: Political Patterns & East-West Paradigms". Journal of Asian History. 41 (2): 107–130. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41933456.

- ^ Carrasco, David; Warmind, Morten; Hawley, John Stratton; Reynolds, Frank; Giarardot, Norman; Neusner, Jacob; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Campo, Juan; Penner, Hans (1999). Wendy Doniger (ed.). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. United States: Merriam-Webster. p. 689. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ^ Hopkins, Keith (July 2001). A World Full of Gods: The Strange Triumph of Christianity. New York: Plume. p. 245. ISBN 0-452-28261-6. OCLC 47286228.

- ^ Coyle, J.K. (2009). Manichaeism and its Legacy. Brill. p. 19.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5000 years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3.

- ^ Rong, Xinjian (24 October 2022). "Gaochang in the Second Half of the 5th Century and Its Relations with the Rouran Qaghanate and the Kingdoms of the Western Regions". The Silk Road and Cultural Exchanges between East and West. Brill. pp. 577–578. doi:10.1163/9789004512597_006. ISBN 978-90-04-51259-7.

- ^ Liu, Xinru (1997). Silk and Religion: An Exploration of Material Life and the Thought of People, AD 600–1200, Parts 600–1200. Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-19-564452-4.