Madeline (book)

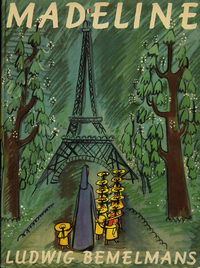

The cover to the original 1939 Madeline children's book. | |

| Author | Ludwig Bemelmans |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Ludwig Bemelmans |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Viking Press |

Publication date | 1939 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) Audiobook |

Madeline is a 1939 book written and illustrated by Ludwig Bemelmans, the first in the book series of six, later expanded by the author's grandson to 17, which inspired the Madeline media franchise. Inspired by the life experiences of its author/illustrator, the book is considered one of the major classics of children's literature through the age range of 3 to 8 years old.[1][2] The book is known for its rhyme scheme and colorful images of Paris, with an appeal to both children and adults.

Background

Madeline was inspired by the experiences of its Austrian-American author and illustrator Ludwig Bemelmans.[3] Bemelmans spent his first years raised in a hotel in Austria, a dull setting in which he was known for causing trouble.[4] His bold traits contrasting with his post-World War I setting is seen depicted through Madeline's daring personality being surrounded by order.[4] Bemelmans was sent to a private school, but after a disciplinary incident was sent to America where he joined the U.S. Army.[4] He took his inspiration from the war and began drawing cartoons of people around his hotel business, which marked the beginning of his interest in illustrating children's books.[5]

The women in Bemelmans' life, including his wife Madeleine and daughter Barbara, inspired the creation of the book's main character Madeline.[4] He also incorporated inspiration from his experience with schooling within the plot, such as through including some of his mother's memories from her time at boarding school.[4] More personal information is found within the plot's portrayal of a traumatic event in Bemelmans' life when he was taken to the hospital after a bicycle accident.[6] This can be seen depicted through the main plot point of Madeline's experience with emergency appendix surgery.[6]

Publishing Madeline was not easy.[6] During his post-war time in America, he met a publisher who encouraged him to write children's books.[6] Ultimately this publisher rejected Madeline for being too sophisticated for a child audience with images that were too expensive to print, leaving Bemelmans to search for a new publishing opportunity.[6]

Plot

The story is set in an all-girls boarding school in Paris, France. The opening rhyming sentences were repeated at the start of the subsequent books in the series:[7]

In an old house in Paris

That was covered in vines

Lived twelve little girls

In two straight lines.

Madeline is the smallest of the girls. She is seven years old, and the only redhead. The group's troublemaker, she is the bravest and most daring of the girls, flaunting at "the tiger in the zoo" and giving Miss Clavel a headache as she goes around the city engaging in all sorts of antics.[8][9]

One night, Miss Clavel wakes up, sensing something wrong. She rushes to the girls' bedroom and sees Madeline crying. A pediatrician named Doctor Cohn is called and takes Madeline to the hospital because she has a ruptured appendix. Hours later, Madeline finds herself recuperating in the hospital. She is greeted by her classmates and Miss Clavel, who gives her flowers and a doll house from her Papa. In return, Madeline shows them her scar. Madeline's classmates and Miss Clavel go home, but Miss Clavel wakes up again to find the other little girls wailing, demanding to "have their appendix out too". Miss Clavel, relieved that the matter is trivial, assures them that they're all well and calls on them to go to sleep.

Style

The aesthetically pleasing style of writing and illustrations within Madeline contribute to its status as a classic.[10] Madeline's pleasing rhyme is a large contribution to its timeless success.[10] The rhyme scheme is representative of themes of regularity and irregularity, seen through its initial symmetrical verse transitioning into pages of mixed meter with irregular rhyme.[3]

A notable technique within the illustrations is the window in the book technique, which creates the effect that the book is an illusion and not reality.[3] The illustrations also balance symmetry and asymmetry between the framing and images which tie into the plot, for example the recurring symbol of the girls walking in two straight lines.[3] There is a balance between order and disorder, seen through the contrast between the symmetry of the buildings and nature against the chaos that occurs within the book's plot.[3]

Analysis

Factors such as being set in Paris and being written during World War II impact how Madeline is read and received.[11] Setting the book in Paris specifically appealed to Americans, especially during World War II, as the city was a symbol of Western civilization.[11] Paris' foreign beauty shown within the book's portrayal of the city's order and perfection built a sense of American longing to visit and protect such an iconically chic place.[11] Bemelmans' paintings are a lasting cultural representation of Paris, and are definitive for those who have never been there to see it for themselves.[9] Bemelmans continued to set his books in an idealistic version of Paris, despite their creation during the chaos of war, maintaining the city's pristine reputation.[9][11] Along with the book promoting a positive representation for Paris, Bemelmans’ expressionistic style of art also directly contributed to the popularity of Madeline.[11] The expressionistic art style was very popular at the time, making the book a success with adults beyond its success with children.[11]

Critical reception

Madeline was named a Caldecott Honor Book for 1940 and a subsequent book in the Madeline series, Madeline's Rescue, earned a Caldecott Medal in 1954.[12] School Library Journal included the book at #47 on their Top 100 Picture Books list in 2012.[13] This book was also an ALA Notable Children's Book.[12][citation needed]

Film

In 1952, this story was adapted into a 6-minute animation by United Productions of America. The film was nominated for the 1952 Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. In 2013, it became available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.[14]

References

- ^ "Top 100 Picture Books #47: Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans". School Library Journal. May 29, 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (3 July 2014). "At 75, Still Stepping Out of Line". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Eastman, Jacqueline F. (1991). "Aesthetic Distancing in Ludwig Bemelmans' Madeline". Children's Literature. 19 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1353/chl.0.0139. S2CID 144693455. Project MUSE 246227 ProQuest 2152975517.

- ^ a b c d e Heins, Ethel (1988). "Ludwig Bemelmans". In Bingham, Jane (ed.). Writers for Children: Critical Studies of Major Authors Since the Seventeenth Century. Scribner's. pp. 55–62. ISBN 978-0-684-18165-3.

- ^ Columbia University, and Paul Lagasse. "Bemelmans, Ludwig". The Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2018

- ^ a b c d e "Bemelmans, Ludwig". Continuum Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Edited by Bernice E. Cullinan, and Diane G. Person. Continuum, London, UK, 2005,

- ^ "At 75 She's Doing Fine; Kids Still Love Their 'Madeline'". NPR. October 11, 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ Bemelmans, Ludwig (1987). Madeline. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-44580-6. OCLC 1298693966.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Bromwich, Jonah E. (27 April 2018). "How the Author of 'Madeline' Created His Most Famous Character". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Baker, Isabel; Schiffer, Miriam Baker (March 2017). "Madeline". YC Young Children. 72 (1): 96. ProQuest 2008817155.

- ^ a b c d e f Eastman, Jacqueline F. "Madeline and the Sequels: The Making of a Classic Series", 1996, pp. 50-62

- ^ a b "Madeline, 1940 Caldecott Honor Book". American Library Association. 2013-07-03. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ Bird, Betsy (2012). "Top 100 Picture Books Poll Results". slj.com. Media Source Inc.

- ^ Bemelmans, Ludwig (1 January 1955). "Madeline". United Productions of America, Released by International Film Bureau. Retrieved 7 December 2016.