Methylenedioxypyrovalerone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, insufflation, intravenous, rectal, vaporization |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Excretion | Primarily urine (renal) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

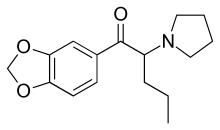

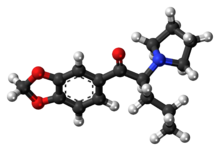

| Formula | C16H21NO3 |

| Molar mass | 275.348 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (abbreviated MDPV, and also called monkey dust[3]) is a stimulant of the cathinone class that acts as a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI).[4][5] It was first developed in the 1960s by a team at Boehringer Ingelheim.[6] Its activity at the dopamine transporter is six times stronger than at the norepinephrine transporter and it is virtually inactive at the serotonin transporter.[4] MDPV remained an obscure stimulant until around 2004 when it was reportedly sold as a designer drug. In the US, products containing MDPV and labeled as bath salts were sold as recreational drugs in gas stations, similar to the marketing for Spice and K2 as incense, until it was banned in 2011.[7]

Appearance

The hydrochloride salt exists as a very fine crystalline powder; it is hygroscopic and thus tends to form clumps, resembling something like powdered sugar. Its color can range from pure white to a yellowish-tan and has a slight odor that strengthens as it colors. Impurities are likely to consist of either pyrrolidine or alpha-dibrominated alkylphenones—respectively, from either excess pyrrolidine or incomplete amination during synthesis. These impurities likely account for its discoloration and fishy (pyrrolidine) or bromine-like odor, which worsens upon exposure to air, moisture, or bases.[8]

Pharmacology

Methylenedioxypyrovalerone has no record of FDA approved medical use.[9] It has been shown to produce robust reinforcing effects and compulsive self-administration in rats, though this had already been provisionally established by a number of documented cases of misuse and addiction in humans before the animal tests were carried out.[10][11]

MDPV is the 3,4-methylenedioxy ring-substituted analog of the compound pyrovalerone, developed in the 1960s, which has been used for the treatment of chronic fatigue and as an anorectic, but caused problems of abuse and dependence.[12]

Other drugs with a similar chemical structure include α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (α-PPP), 4'-methyl-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (M-α-PPP), 3',4'-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (MDPPP) and 1-phenyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-pentanone (α-PVP).

Effects

MDPV acts as a stimulant and has been reported to produce effects similar to those of cocaine, methylphenidate, and amphetamines.[13]

The primary psychological effects have a duration of roughly 3 to 4 hours, with aftereffects such as tachycardia, hypertension, and mild stimulation lasting from 6 to 8 hours.[13] High doses have been observed to cause intense, prolonged panic attacks in stimulant-intolerant users,[13] and there are anecdotal reports of psychosis from sleep withdrawal and addiction at higher doses or more frequent dosing intervals.[13] It has also been repeatedly noted to induce irresistible cravings to re-administer.[13][14]

Reported modalities of intake include oral consumption, insufflation, smoking, rectal and intravenous use. It is supposedly active at 3–5 mg, with typical doses ranging between 5–20 mg.[13]

When assayed in mice, repeated exposure to MDPV causes not only an anxiogenic effect but also increased aggressive behaviour, a feature that has already been observed in humans. As with MDMA, MDPV also caused a faster adaptation to repeated social isolation.[15]

A cross-sensitization between MDPV and cocaine has been evidenced.[16] Furthermore, both psychostimulants, MDPV and cocaine, restore drug-seeking behavior with respect to each other, although relapse into drug-taking is always more pronounced with the conditioning drug. Moreover, memories associated with MDPV require more time to be extinguished. Also, in MDPV-treated mice, a priming-dose of cocaine triggers significant neuroplasticity, implying a high vulnerability to its abuse.[17]

Long-term effects

The long-term effects of MDPV on humans have not been studied, but it has been reported that mice treated with MDPV during adolescence show reinforcing behavior patterns to cocaine that are higher than the control groups. These behavioural changes are related to alterations of factor expression directly related to addiction. All this suggests an increased vulnerability to cocaine abuse.[18]

Metabolism

MDPV undergoes CYP450 2D6, 2C19, 1A2,[19] and COMT phase 1 metabolism (liver) into methylcatechol and pyrrolidine, which in turn are glucuronated (uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyl-transferase) allowing it to be excreted by the kidneys, with only a small fraction of the metabolites being excreted into the stools.[20] No free pyrrolidine will be detected in the urine.[21]

Molecularly, this is seen as demethylenation of methylenedioxypyrovalerone (CYP2D6), followed by methylation of the aromatic ring via catechol-O-methyl transferase. Hydroxylation of both the aromatic ring and side chain then takes place, followed by an oxidation of the pyrrolidine ring to the corresponding lactam, with subsequent detachment and ring opening to the corresponding carboxylic acid.[22]

Detection in biological specimens

MDPV may be quantified in blood, plasma or urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to provide evidence in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma MDPV concentrations are expected to be in a range of 10–50 μg/L in persons using the drug recreationally, >50 μg/L in intoxicated patients, and >300 μg/L in victims of acute overdose.[23]

Legality

In 2010, a 33-year-old Swedish man was sentenced to six years in prison by an appellate court, Hovrätt, for possession of 250 grams of MDPV that had been acquired prior to criminalization.[24]

Australia

In Western Australia, MDPV has been banned under the Poisons Act 1964, having been included in Appendix A Schedule 9 of the Poisons Act 1964 as from February 11, 2012. The Director of Public Prosecutions for Western Australia announced that anyone intending to sell or supply MDPV faces a maximum $100,000 fine or 25 years in jail. Users face a $2000 fine or two years' jail. Therefore, anyone caught with MDPV can be charged with possession, selling, supplying or intent to sell or supply.[25]

Canada

Canadian Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq announced on June 5, 2012, that MDPV would be listed on Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which was realized on September 26, 2012.[26]

Finland

MDPV is specifically listed as a controlled substance in Finland (listed appendix IV substance as of June 28, 2010),[27]

United Kingdom

In the UK, following the ACMD's report on substituted cathinone derivatives,[14] MDPV is a Class B drug under The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2010, making it illegal to sell, buy, or possess without a license.[28][29]

United States

In the United States, MDPV is a DEA federally scheduled drug. On October 21, 2011, the DEA issued a temporary one-year ban on MDPV, classifying it as a schedule I substance. Schedule I status is reserved for substances with a high potential for abuse, no currently accepted use for treatment in the United States and a lack of accepted safety standards for use under medical supervision.[30]

Before the federal ban was announced, MDPV was already banned in Louisiana and Florida.[31] On March 24, 2011, Kentucky passed bill HB 121, which makes MDPV, as well as three other cathinones, controlled substances in the state. It also makes it a Class A misdemeanor to sell the drug, and a Class B misdemeanor to possess it.[32]

MDPV is banned in New Jersey under Pamela's Law. The law is named after Pamela Schmidt, a Rutgers University student who was murdered in March 2011 by an alleged user of MDPV.[33] A toxicology report later found no "bath salts" in his system.[34]

On May 5, 2011, Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam signed a law making it a crime "to knowingly produce, manufacture, distribute, sell, offer for sale or possess with intent to produce, manufacture, distribute, sell, or offer for sale" any product containing MDPV.[35]

On July 6, 2011, the governor of Maine signed a bill establishing fines for possession and penalties for trafficking of MDPV.[36]

On October 17, 2011, an Ohio law banning synthetic drugs took effect barring selling and/or possession of "any material, compound, mixture, or preparation that contains any quantity of the following substances having a stimulant effect on the central nervous system, including their salts, isomers, and salts of isomers", listing ephedrine and pyrovalerone. It also specifically includes MDPV.[37] Four days after this Ohio law was passed, the DEA's national emergency ban was implemented.[30]

On December 8, 2011, under the Synthetic Drug Control Act, the US House of Representatives voted to ban MDPV and a variety of other synthetic drugs that had been legally sold in stores.[38]

Documented fatalities

In April 2011, two weeks after being reported missing, two men in northwestern Pennsylvania were found dead in a remote location on government land. The official cause of death of both men was hypothermia, but toxicology reports later confirmed that both Troy Johnson, 29, and Terry Sumrow, 28, had ingested MDPV shortly before their deaths. "It wasn't anything to kill them, but enough to get them messed up," the county coroner said. MDPV containers were found in their vehicle along with spoons, hypodermic syringes and marijuana paraphernalia. In April 2011, an Alton, Illinois, woman apparently died from an MDPV overdose.[39] In May 2011, the CDC reported a hospital emergency department (ED) visit after the use of "bath salts" in Michigan. One person was reported dead on arrival at the ED. Associates of the dead person reported that he had used bath salts. His toxicology results revealed high levels of MDPV in addition to marijuana and prescription drugs. The primary factor contributing to death was cited as MDPV toxicity after autopsy was performed.[40] An incident of hemiplegia has been reported.[41]

A total of 107 non-fatal intoxications and 99 analytically confirmed deaths related to MDPV between September 2009 and August 2013 were reported by nine European countries.[2]

Overdose treatment

Physicians often treat MDPV overdose cases with anxiolytics, such as benzodiazepines, to lessen the drug-induced activity in the brain and body.[42] In some cases, general anaesthesia was used because sedatives were ineffective.[43]

Treatment in the emergency department for hypertensive emergency, tachycardia, agitation, or seizures consists of large doses of lorazepam in 2–4 mg increments every 10–15 minutes intravenously or intramuscularly. If this is not effective, haloperidol is an alternative treatment. It is suggested that the use of beta blockers to treat hypertension in these patients can cause an unopposed peripheral alpha-adrenergic effect with a dangerous paradoxical rise in blood pressure.[44] Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been shown to improve persistent psychotic symptoms associated with repeated MDPV use.[45][46]

See also

References

- ^ "Substance Details 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone". Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "EMCDDA–Europol Joint Report on a new psychoactive substance: MDPV (3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone)" (PDF). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). January 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Monkey dust "epidemic" causing drug users to experience violent hallucinations". Newsweek. August 10, 2018. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, et al. (March 2013). "Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive 'bath salts' products". Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (4): 552–62. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.204. PMC 3572453. PMID 23072836.

- ^ Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, et al. (January 2013). "Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro". British Journal of Pharmacology. 168 (2): 458–70. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. PMC 3572571. PMID 22897747.

- ^ US 3478050, Koppe H, Ludwig G, Zeile K, "1-(3',4'-methylenedioxy-phenyl)-2-pyrrolidino-alkanones-(1)", issued November 1969, assigned to CH Boehringer Sohn AG and Co and KG Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH.

- ^ Slomski A (December 2012). "A trip on "bath salts" is cheaper than meth or cocaine but much more dangerous". JAMA. 308 (23): 2445–7. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.34423. PMID 23288310.

- ^ Brandt SD, Freeman S, Sumnall HR, Measham F, Cole J (September 2011). "Analysis of NRG 'legal highs' in the UK: identification and formation of novel cathinones". Drug Testing and Analysis. 3 (9): 569–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.687.9467. doi:10.1002/dta.204. PMID 21960541.

- ^ Westphal F, Junge T, Rösner P, Sönnichsen F, Schuster F (September 2009). "Mass and NMR spectroscopic characterization of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone: a designer drug with alpha-pyrrolidinophenone structure". Forensic Science International. 190 (1–3): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.05.001. PMID 19500924.

- ^ Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Nemirovsky NE, Sewalia K, Grabenauer M, Thomas BF, et al. (March 2014). "Potent rewarding and reinforcing effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)". Addiction Biology. 19 (2): 165–74. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00474.x. PMC 3473160. PMID 22784198.

- ^ Coppola M, Mondola R (January 2012). "3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV): chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of a new designer drug of abuse marketed online". Toxicology Letters. 208 (1): 12–5. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.10.002. PMID 22008731.

- ^ Seeger E (October 1964). "US Patent 3314970 – α-Pyrrolidino ketones". Boehringer Ingelheim. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Report on MDPV" (PDF). Drugs of Concern. DEA. May 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ a b "Consideration of the Cathinones" (PDF). Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. March 31, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Duart-Castells L, López-Arnau R, Buenrostro-Jáuregui M, Muñoz-Villegas P, Valverde O, Camarasa J, et al. (January 2019). "Neuroadaptive changes and behavioral effects after a sensitization regime of MDPV". Neuropharmacology. 144: 271–281. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.10.005. hdl:2445/148191. PMID 30321610. S2CID 53208116.

- ^ Duart-Castells L, López-Arnau R, Vizcaíno S, Camarasa J, Pubill D, Escubedo E (May 2019). "7,8-Dihydroxyflavone blocks the development of behavioral sensitization to MDPV, but not to cocaine: Differential role of the BDNF-TrkB pathway". Biochemical Pharmacology. 163: 84–93. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2019.02.004. hdl:2445/130480. PMID 30738029. S2CID 73433868.

- ^ Duart-Castells L, Blanco-Gandía MC, Ferrer-Pérez C, Puster B, Pubill D, Miñarro J, et al. (June 2020). "Cross-reinstatement between 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and cocaine using conditioned place preference". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 100: 109876. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109876. PMID 31991149. S2CID 210896469.

- ^ López-Arnau R, Luján MA, Duart-Castells L, Pubill D, Camarasa J, Valverde O, Escubedo E (May 2017). "Exposure of adolescent mice to 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone increases the psychostimulant, rewarding and reinforcing effects of cocaine in adulthood". British Journal of Pharmacology. 174 (10): 1161–1173. doi:10.1111/bph.13771. PMC 5406300. PMID 28262947.

- ^ Kalapos MP (December 2011). "[3,4-methylene-dioxy-pyrovalerone (MDPV) epidemic?]". Orvosi Hetilap. 152 (50): 2010–9. doi:10.1556/OH.2011.29259. PMID 22112374.

- ^ Strano-Rossi S, Cadwallader AB, de la Torre X, Botrè F (September 2010). "Toxicological determination and in vitro metabolism of the designer drug methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 24 (18): 2706–14. Bibcode:2010RCMS...24.2706S. doi:10.1002/rcm.4692. PMID 20814976.

- ^ Michaelis W, Russel JH, Schindler O (May 1970). "The metabolism of pyrovalerone hydrochloride". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (3): 497–503. doi:10.1021/jm00297a036. PMID 5441133.

- ^ Meyer MR, Du P, Schuster F, Maurer HH (December 2010). "Studies on the metabolism of the α-pyrrolidinophenone designer drug methylenedioxy-pyrovalerone (MDPV) in rat and human urine and human liver microsomes using GC-MS and LC-high-resolution MS and its detectability in urine by GC-MS". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 45 (12): 1426–42. Bibcode:2010JMSp...45.1426M. doi:10.1002/jms.1859. PMID 21053377.

- ^ Baselt RC (2014). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man. Seal Beach, Ca.: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1321–1322. ISBN 978-0-9626523-9-4.

- ^ "Hovrätten skärper straff i MDPV-dom". Norrköpings Tidningar (in Swedish). June 4, 2010. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Emerging drug, MDPV banned in WA". Government of Western Australia. February 8, 2012. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "'Bath salts' drug ingredient banned in Canada". CBC News. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Naantalissa A (June 28, 2010). "Finlex: huumausaineina pidettävistä aineista, valmisteista ja kasveista annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen liitteen IV muuttamisesta". Oikeusministeriö (in Finnish). Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "A change to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 : Control of mephedrone and other cathinone derivatives". Home Office. April 16, 2010. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2010". Home Office. April 12, 2010. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ a b "Chemicals Used in "Bath Salts" Now Under Federal Control and Regulation" (Press release). Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). October 21, 2011. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Allen G (February 8, 2011). "Florida Bans Cocaine-Like 'Bath Salts' Sold in Stores". NPR. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Beshear S (March 23, 2011). "Gov. Beshear signs law banning new synthetic drugs" (Press release). Commonwealth of Kentucky. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Rowe A (September 2, 2011). "Governor bans bath salts after student's death". Daily Targum. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Giambusso D (September 2, 2011). "Cranford man charged with murdering girlfriend; Toxicology report shows no trace of 'bath salts'". Nj.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "State of Tennessee Public Chapter No. 169 House Bill No. 457" (PDF). State of Tennessee. April 18, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 20, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "New law sets fine at $350 for 'bath salts' possession". Portland Press Herald. July 7, 2011. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Ohio Amendment to Controlled Substances Act HB 64". Ohio General Assembly Archives. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ Kreider R (December 8, 2011). "House Votes to Ban 'Spice,' 'Bath Salts'". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Wilson T (May 12, 2011). "Illinois lawmakers target bath salts used as a drug". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Emergency Department Visits After Use of a Drug Sold as "Bath Salts" --- Michigan, November 13, 2010 – March 31, 2011". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 60, no. 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). May 2011. pp. 624–627. PMID 21597456. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Boshuisen K, Arends JE, Rutgers DR, Frijns CJ (May 2012). "A young man with hemiplegia after inhaling the bath salt "Ivory wave"". Neurology. 78 (19): 1533–4. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182553c70. PMID 22539576. S2CID 22029215.

- ^ Salter J, Jim S (April 6, 2011). "Synthetic drugs sent thousands to ER". NBC News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Goodnough A, Zezima K (July 16, 2011). "An Alarming New Stimulant, Legal in Many States". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ ""Bath Salts" Health Care Provider Fact Sheet" (PDF). Michigan Department of Community Health. April 30, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Penders TM, Gestring RE, Vilensky DA (November 2012). "Intoxication delirium following use of synthetic cathinone derivatives". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 38 (6): 616–7. doi:10.3109/00952990.2012.694535. PMID 22783894. S2CID 207428569.

- ^ Penders TM, et al. (December 2013). "Electroconvulsive Therapy Improves Persistent Psychosis After Repeated Use of Methylenedioxypyrovalerone ("Bath Salts")". The Journal of ECT. 29 (4): 59–60. doi:10.1097/YCT.0b013e3182887bc2. PMID 23609518. S2CID 45842375.

External links

Meltzer PC, Butler D, Deschamps JR, Madras BK (February 2006). "1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-pentan-1-one (Pyrovalerone) analogues: a promising class of monoamine uptake inhibitors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 49 (4): 1420–32. doi:10.1021/jm050797a. PMC 2602954. PMID 16480278.

Meltzer PC, Butler D, Deschamps JR, Madras BK (February 2006). "1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-pentan-1-one (Pyrovalerone) analogues: a promising class of monoamine uptake inhibitors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 49 (4): 1420–32. doi:10.1021/jm050797a. PMC 2602954. PMID 16480278.- Erowid MDPV Vault