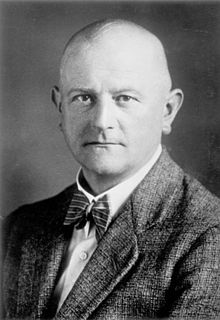

Ludwig Müller

Johan Heinrich Ludwig Müller (23 June 1883 – 31 July 1945) was a German theologian, a Lutheran pastor,[1] and leading member of the pro-Nazi "German Christians" (German: Deutsche Christen) faith movement. In 1933 he was appointed by the Nazi Party as Reichsbischof ("Bishop for the Reich") of the German Evangelical Church (German: Deutsche Evangelische Kirche).

Life

Müller was born in Gütersloh, in the Prussian province of Westphalia, where he attended the Pietist Evangelical Gymnasium. He went on to study Protestant theology at the universities of Halle and Bonn. Having finished his studies, he worked as a school inspector in his hometown, from 1905 also as a vicar and assistant preacher in Herford and Wanne. In 1908 he became parish priest in Rödinghausen. At the outbreak of World War I, he served as a Navy chaplain in Wilhelmshaven.

After the war, Müller joined Der Stahlhelm paramilitary organization and continued his career as a military chaplain, from 1926 at the Königsberg garrison. He had been associated with Nazism since the 1920s, supporting a revisionist view of "Christ the Aryan" (or a "heroic Jesus") as well as a plan of purifying Christianity of what he deemed "Jewish corruption," including purging large parts of the Old Testament.

Müller had little real political experience and, as his actions would demonstrate to Adolf Hitler, little if any political aptitude. In the 1920s and early 1930s, before Hitler's assumption of the German chancellorship on 30 January 1933, he was a little-known pastor and a regional leader of the German Christians in East Prussia. However, he was an "old fighter" with Hitler (German: Alter Kämpfer) since 1931, when he joined the Nazi Party, and had a burning desire to assume more power.[2] In 1932, Müller introduced Hitler to Reichswehr General Werner von Blomberg when Müller was chaplain of the East Prussian Military District and Blomberg was the district's commander.[3]

As part of the Gleichschaltung process, the Nazi regime's plan was to "coordinate" all 28 separate Protestant regional church bodies into a single and unitary Reichskirche ("Church of the Reich"). Müller wanted to serve as Reichsbischof of this newly formed entity.[4] His first attempt to achieve his post ended in a miserable and embarrassing failure, when the German Evangelical Church Confederation and the Prussian Union of churches designated Friedrich von Bodelschwingh on 27 May 1933. Eventually, however, after the Nazis had forced Bodelschwingh's resignation, Müller was appointed regional bishop (Landesbischof) of the Prussian Union on 4 August, and on 27 September finally was elected Reichsbischof by a national synod through political machinations. On 13 September 1933, Prussian Minister President Hermann Göring appointed him to the Prussian State Council.[5]

Müller's advancement angered many Protestant pastors and congregations, who deemed his selection to be politically motivated and intrinsically anti-Christian. Still regional bishop, he handed over more powers to the Reichsbischof—himself—as an example of imitation, to the discontent of other regional bishops like Theophil Wurm (Württemberg). On the other hand, Müller's support by the "German Christians" within the Protestant Church decreased, as he was not able to wield explicit authority. The radical Nazi faction wanted to get rid of the Old Testament and create a German National Religion divorced from Jewish-influenced ideas. They supported the introduction of the Aryan Paragraph into the Church. This controversy led to schism and the foundation of the competing Confessing Church, a situation that frustrated Hitler and led to the end of Müller's power.

Many of the German Protestant clergy supported the Confessing Church movement, which resisted the imposition of the state into Church affairs.[6] With Hitler's interest in the group having waned by 1937, and the party taking a more aggressive attitude toward the resistant Christian clergy, Müller tried to revive his support by allowing the Gestapo to monitor churches and consolidating Christian youth groups with the Hitler Youth.

He remained committed to Nazism to the end. He died of suicide[citation needed] in Berlin in 1945, soon after the Nazi defeat.

Notes

- ^ Romocea, Cristian (2011). Church and State: Religious Nationalism and State Identification in Post-Communist Romania. Bloomsbury. p. 54. ISBN 9781441137470.

- ^ Barnett p. 33.

- ^ Shirer p. 235

- ^ See article on Confessing Church for the background of the Protestant Church in Germany.

- ^ Lilla 2005, p. 224.

- ^ Stackelberg, Roderick; Winkle, Sally A. (2002). The Nazi Germany sourcebook : an anthology of texts. London: Routledge. pp. 167–68. ISBN 0-415-22213-3.

References

- Barnes, Kenneth C. (1991). Nazism, Liberalism, & Christianity: Protestant Social thought in Germany & Great Britain, 1925-1937. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1729-1. (Barnes)

- Barnett, Victoria (1992). For the Soul of the People: Protestant Protest Against Hitler. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-512118-X. (Barnett)

- Hockenos, Matthew D. (2004). A Church Divided: German Protestants Confront the Nazi Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34448-9. (Hockenos)

- Lilla, Joachim (2005). Der Preußische Staatsrat 1921–1933: Ein biographisches Handbuch. Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag. ISBN 978-3-770-05271-4.

- Rev. Howard Chandler Robbins (1876–1952), The Germanisation of the New Testament by Bishop Ludwig Müller and Bishop Weidemann, London, 1938