Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández Cortina

Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández Cortina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández Cortina[1] 1863 Jaén, Spain |

| Died | 1939 Jaén, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation(s) | lawyer, entrepreneur |

| Known for | politician, publisher |

| Political party | Carlism |

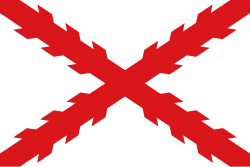

Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández Cortina (1863–1939) was a Spanish politician and publisher. Politically he supported the Carlist cause, though in the mid-1930s he assumed a somewhat dissident stand and co-led a faction known as Cruzadistas. His career climaxed in 1908-1910, when he served in the lower chamber of the Cortes. Within the party ranks during two spells of 1912-1913 and 1929-1932 he served in the national executive Junta Nacional, and in 1929-1932 he held the regional jefatura in New Castile. As a publisher in the 1890s and 1900s he founded and animated minor titles issued in eastern Andalusia, but is better known as one of key figures behind Madrid-based Carlist periodicals, El Correo Español (1919–1921) and El Cruzado Español (1929–1936). As an entrepreneur he was engaged in banking, olive oil, hydroelectricity and mining businesses.

Family and youth

Sáenz's paternal ancestors were related to Rioja. His grandfather, Manuel Sáenz García (b. 1799), originated from Ortigosa de Cameros and belonged to petty nobility;[2] he married Celestina García Rubio, a girl from the nearby Rasillo de Cameros, whose brother León in the 1820s would open one of the first banks in Jaén.[3] The son of Manuel and Celestina, also Manuel Sáenz García (1828–1904),[4] though born in Ortigosa at one point moved to Jaén and joined the family-related banking business, which since the mid-19th century became a very successful enterprise; he got known as a banquero.[5] Around 1863[6] he married Joaquína Fernández y Fernández Cortina (died 1914).[7] Her ancestors originated from Pendueles (Llanes, Asturias)[8] and her maternal uncles were Joaquín and Lorenzo Fernandez Cortina, the former the bishop of Sigüenza and the latter the canónigo in Jaén.[9] Though born in Asturias she moved to Jaén, where her brother Manuel Férnandez Cortina[10] became the co-founder of Colegio de Abogados and one of the most prestigious citizens of Jaén.[11]

Manuel and Joaquína settled in Jaén and formed part of the local financial oligarchy. It is not known how many children they had, though Lorenzo had at least 3 brothers, Joaquín,[12] Juan[13] and Manuel;[14] it is not clear who was the oldest one,[15] yet Lorenzo outlived all of them.[16] None of the sources consulted provides any information on his early education, though some suggest that he frequented schools in Rioja, perhaps in Logroño.[17] In 1878 he entered Facultad de Derecho at Universidad Central in Madrid.[18] One source maintains that in 1884 he became Doctor en Civil y Canónico thanks to the thesis Reglas equitativas para tratar la línea divisoria entre ambas potestades, o sea, entre los derechos e intereses de la Iglesia y el Estado.[19] Another author claims that in 1883 he became licenciado en derecho,[20] while in 1885 he majored in civil and canon law;[21] one more source notes that his dissertation was accepted as sobresaliente.[22] In 1888 Sáenz entered Colegio de Abogados de Jaén, yet it is not known whether he commenced own practice.[23]

In 1893[24] Sáenz married Antonia Dosal Sobrino (1872–1933);[25] since she was from Llanes, Lorenzo probably came to know her due to his maternal family links.[26] Her mother[27] was sister to very successful indianos, who thanks to textile business made a fortune in Mexico but who died with no descendancy.[28] The wealth was first inherited by Antonia's brother Sinforiano,[29] but following his childless death part of it eventually passed to her;[30] its crown was the estate in Llanes, known as La Concepción[31] or Palacio Sinforiano.[32] Lorenzo and Antonia lived mostly in Madrid, where he joined the local Colegio de Abogados.[33] They owned a luxurious apartment next to the Cortes building,[34] yet they used to spend long spells in Llanes and Jaén, where he co-owned the family economy. They had no children.[35] Among more distant relatives, Lorenzo's sister-in-law became condesa de Mendoza Cortina,[36] while his brother (who prior to 1905 served as alcalde of Jaén)[37] married condesa de Humanes.[38]

First publishing projects (1890s)

Sáenz inherited political outlook from his father, who was an active Carlist and in the 1890s formed part of the local party executive, Junta Provincial de Jaén.[39] Lorenzo was not noted in Carlist structures before in 1889 he launched a local Jaén-based weekly, El Norte Andaluz. It was not openly Traditionalist (last Traditionalist title disappeared in Jaén in 1877), posed as Catholic periodical, sub-titled "periodico de intereses morales y materiales",[40] and by scholars is described as "cercano al carlismo". Co-edited with Bartolomé Romero Gago, the future Seville cathedral canon, it was barely more than a 4-page bulletin, dedicated mostly to religious issues. The last issue appeared in 1891. According to friendly newspapers, the closing of El Norte resulted from " una conspiración íntegro-conservadora".[41] This conspiracy was principally about later launch of the local Integrist bi-weekly, El Pueblo Católico;[42] since then, hostility towards the Integrists would mark Sáenz's activity for some 45 years to come. Scholars summarize the episode by noting that "la importancia objetiva de El Norte Andaluz es escasa".[43]

In the early and mid-1890s Sáenz emerged as major figure in local lay Catholic circles. He served as "corresponsal de esta Diócesis"[44] and later as secretario of Junta Diocesana, entrusted e.g. with collecting money for various projects;[45] as the representative of Jaén he attended Congreso Católico in Zaragoza,[46] and remained engaged in other local activities. He gained status also in Carlist structures. In 1895 he was first noted as member of Junta Provincial de Jaén[47] and as such kept signing various declarations,[48] e.g. in 1896.[49] In 1897 he was elected presidente honorario of the local Jaén círculo[50] and in 1898 served as president of another local organization.[51] In the mid-1890s he was also admitted as member-correspondent to Real Academia de la Historia[52] (unclear on what basis)[53] and friendly titles referred to him as "joven abogado é ilustrado periodista".[54]

Though since the mid-1890s Sáenz shuttled between Jaén and Madrid, where he established his primary residence, in 1896 he launched another Andalusian publishing project, the weekly El Libertador; this time it was based in Ubeda. Clearly identified as Traditionalist and with "Dios, Patria, Rey" as sub-title, it was issued on Saturdays. The weekly was managed mostly by Fernando del Moral Almagro and like El Norte Andaluz it was also a simple, 4-page print on 4-columns; the content was somewhat more diverse, with religious issues discussed along national or local news and a cultural column present. The weekly pledged Catholic orthodoxy, yet its ultra-intransigent stand at one point produced controversy: Victoriano Guisasola Menéndez, the future primate of Spain and at the time the bishop of Jaén, lambasted the paper for re-publishing of an article titled Obispos liberales, Obispos arrianos, aimed against allegedly liberal hierarchs.[55] In 1899 El Libertador was moved to Jaén,[56] where it first continued as a bi-weekly[57] and then closed in 1900.[58]

Jaén, Madrid, and Llanes (turn of centuries)

Since his 1893 marriage Sáenz entered Carlist structures in Asturias, where he became honorary president of Junta Tradicionalista in Llanes,[59] the municipio of his mother and his wife. Since removal to Madrid he was also increasingly engaged in the party organization in the capital. In 1896 the local círculo tradicionalista elected him to its Junta Directiva, where he assumed the post of secretario general as well;[60] this was to last for some years to come.[61] In Traditionalist party press he was listed among prominent figures when taking part in local events, e.g. in the funeral of marquesa de Cerralbo, wife to the Carlist national leader.[62] However, in official structures of the Carlist organization, at the time named Comunión Católico-Monárquica, he double-hatted; apart from duties in Madrid he remained also member of the Jaén executive, until the early 1900s headed by Eusebio Sanchez Perez.[63]

In the early 1900s Sáenz was engaged in a number of professional activities. He was a lawyer in Madrid,[64] at times referred to as "conocido jurisconsulto".[65] In his native Jaén, apart from shares in the family banking business, together with brothers he owned a large plant, producing olive oil,[66] and an Eléctrica de San Rafael hydro-power installation on the Guadalquivir.[67] In Asturias he was co-gerente and administrador of Hidroeléctrica Purón, a company based in Llanes[68] and operating small power stations on Purón and Barbalin streams.[69] Around 1905 he engaged also in mining industry; he applied for license for exploring iron ore near Llanes, in the pit known as "La Especial"[70] and located at estates owned with his wife, also on the banks of Purón.[71] It seems he indeed tried exploration for some time,[72] yet after 1910 there is no information on any further activity.

In 1901 Sáenz one more time tried his hand in the publishing business. Described in historiography as "infatigable creador de órganos de esta significación política [Carlism]",[73] in Úbeda he launched a bi-weekly El Combate. It was managed mostly by an experienced local editor, Rufino Peinado Peinado, who since 1905 formally acted as its director. El Combate assumed an openly Carlist stand and is referred to as "el más duradero de los tres periódicos que anima y financia";[74] it was counted among periodicals "oficialmente carlistas".[75] After few years and because of limited success, it was re-formatted as a weekly; periodically it published also a doctrinal companion, Hoja quincenal de El Combate.[76] The weekly proved the longest-lasting of Sáenz's Andalusian publishing projects; it kept appearing until 1911.[77] At the time Sáenz emerged also as the leader of provincial Carlism in Jaén; in 1905 he replaced Eusebio Sanchez Perez as presidente efectivo of Junta Provincial Tradicionalista.[78] Local branches across the province nominated him presidente honorario, e.g. in Alcalá la Real[79] or in Villacarrillo.[80]

In and around Cortes (1910s)

In 1908 the Carlist deputy to the Cortes from Navarre, Eduardo Castillo de Pineyro, died; in such case the electoral regime required by-elections to nominate his replacement. The Carlist executive appointed Sáenz to stand; he had no links to Navarre, yet as by-election was to take place in the district of Tudela, in the Ribera Navarra region on the left bank of the Ebro, he was marketed[81] as the one who "tiene cerca del distrito la circunstancia grata de ser oriundo de la noble tierra que baña el Ebro, donde ha hecho sus estudios", a reference to his links to La Rioja, on the other side of the river.[82] There was limited interest among the electors, as only 3.622 of 11.028 bothered to vote, yet 99% preferred Sáenz[83] over his liberal and government-supported counter-candidate, Mariano Aisa y Cabrerizo, barón de la Torre.[84] His mandate lasted barely 2 years before the parliament term expired in 1910; during this time he was reported in the press as co-fathering an amendment to law on railways,[85] delivering a speech on budgetary contribution to refurbishment of churches[86] and on operations of the post office.[87]

In the late 1900s Sáenz as a Cortes deputy featured in numerous Carlist propaganda events,[88] e.g. in 1908 Santander[89] or in 1909 in Palencia;[90] in 1909 he attended the funeral of the claimant in Trieste.[91] In the 1910 electoral campaign he tried to renew his ticket, also from Tudela,[92] formally running on the Coalicion Católica list.[93] Following very fierce competition initially he was declared triumphant over his liberal counter-candidate Salvador Guardiola,[94] but the latter protested numerous irregularities;[95] they ranged from women bullying their husbands[96] to plain corruption.[97] Though initially Tribunal Supremo confirmed that Sáenz got 4.902 votes and Guardiola 4.742 votes,[98] eventually the new Cortes declared Sáenz's mandate void.[99]

During the following campaign of 1914 Sáenz once again appeared as the Carlist candidate in Tudela; he was among 20 candidates of the party nationwide and among 3 party candidates in Navarre.[100] However, at the time the Carlist grip on the region, evident mostly in the early 1900s, was already less firm, due to the pursued strategy of pivotal alliances and the resulting bewilderment of the electorate. This time he faced the conservative datista counter-candidate, José M. Méndez Vigo, marquez de Montalvo. Out of 9.357 votes cast, Sáenz got 47% compared to 52% of his rival;[101] this time it was Sáenz who protested irregularities, but to no avail.[102] In the following elections of 1916 Sáenz did not stand; the Carlist candidate from Tudela was Luis Martínez Kleiser (from Asturias), who anyway lost to Méndez Vigo.[103] During the 1919 campaign Sáenz did not compete, but acted as "delegado electoral", the chief party representative acting in front of electoral authorities.[104]

In and around Junta Nacional (1910s)

Since 1905 Jefe Provincial in Jaén, Sáenz kept rising also within central Carlist structures. Some time prior to 1909 he was nominated "Secretario de la Jefatura delegada de la Comunión Católico-Monárquica".[105] Since the turn of the decades he became increasingly active as to party finances, first launching and then animating subscriptions for Casa de los Tradicionalistas in Madrid, the building supposed to be sort of a Traditionalist cultural centre in the capital; it was also to host editorial and printing facilities of El Correo Español, the unofficial party mouthpiece.[106] Following reorganization of central executive, in 1911 he was nominated - together with Celestino Alcocer - Tesorero de la Tradición.[107] He was busy on fund-raising tours across the country,[108] though probably the lion's share of the capital collected came thanks to one single donation.[109] The project was crowned with success in 1912, when during a pompous ceremony and with him speaking[110] the imposing Casa de los Tradicionalistas opened at Calle de Pizarro 14; the most important part of the site was modern printing machinery of El Correo.[111]

In 1912 Sáenz was officially nominated to the national executive, Junta Nacional; though the body was composed of regional leaders and his native Andalusia was represented by its Jefe Regional José Diez de la Cortina, Sáenz was appointed on additional basis.[112] Following yet another reshuffle in 1913 he entered the section of Industria y Comercio of new junta general extraordinaria and Junta Directiva of Casa de los Tradicionalistas.[113] The same year Junta Nacional set up 10 specialized commissions; together with marqués de Vesolla and conde Rodezno he was nominated to the one named Tesoro de la Tradición. However, Sáenz declined the nomination.[114] None of the sources consulted provides clarification, and in particular it is not clear whether his decision was conditioned by growing internal division within Carlism, increasingly divided between followers of the key theorist Juan Vázquez de Mella and these supporting the king, Don Jaime.[115]

The conflict between the Mellistas and the Jaimistas escalated during the Great War, as the former opted for the Central Powers (technically for neutrality) and the latter for the Entente. The position assumed by Sáenz was peculiar: together with Guillermo Izaga, Emilio Dean, Juan Perez Najera and Bartolomé Feliú he formed the faction which favored Germany, but opposed de Mella and his political sponsor, the party leader marqués de Cerralbo.[116] With Don Jaime incomunicado in his house arrest in Austria, Junta Nacional was increasingly paralyzed; Sáenz "continuaría con la vía restrictiva ortodoxia jaimista".[117] The long-standing feud was brought to the climax in early 1919, when during open confrontation Don Jaime, back in France, expulsed de Mella and his supporters. The breakup decimated the Carlist command layer and in particular its publishing network, as numerous titles joined the rebels.[118] At one point it seemed that this would be also the fate of El Correo Español; however, it was largely thanks to decisive action of Sáenz, fully loyal to his king, that takeover by the Mellistas has been prevented.[119]

From El Correo to El Cruzado (1919-1929)

In late 1919 Sáenz attended so-called Magna Junta de Biarritz, a grand congregation of leaders who remained loyal to Don Jaime; the purpose was to set the course for the future.[120] It was there where he was nominated Tesorero de la Tradición,[121] the man responsible for party finances; later this role was described as "tesorero general de la Comunión".[122] His main task was to save El Correo Español, struggling following the Mellista secession. He was active in the press and during public meetings, asking for donations and subscriptions;[123] sales of booklets with his address delivered in Biarritz was part of the scheme.[124] In 1920 the ownership structure changed, as El Correo became the property of newly established Editorial Tradicionalista publishing house; he called to buy shares of the company.[125] All this produced little effect. Despite Sáenz's own large donation, made in early 1921,[126] later that year and following 33 years of continuous presence on the market, the daily closed.[127]

In 1923 Sáenz was nominated vice-president (presidency went to Rodezno) of special committee, supposed to propose re-organization scheme for Comunión Jaimista;[128] however, the advent of Primo dictatorship in 1923 brought political life to a standstill. In the early 1920s Sáenz - still resident in his Madrid luxurious apartment - was reported engaged merely in meta-political activities, like a rally in Lourdes[129] or observance of Carlist feasts (in Madrid he co-presided over Mártires de la Tradición).[130] In 1924 Don Jaime conferred upon him the title of Caballero de la Orden de Legitimidad Proscripta, the highest Carlist distinction,[131] and in the mid-1920s Sáenz was regularly presents at Madrid religious services, organized on the nameday of the claimant.[132] In the press he was noted either on societe columns[133] or in relation to his private financial dealings in Llanes.[134]

In the late 1920s and on explicit orders from the claimant, Sáenz commenced efforts to launch a newspaper which would serve as an unofficial party mouthpiece, possibly a continuation of El Correo Español. Though there were well-established Carlist dailies issued in provincial capitals, e.g. in Pamplona or Barcelona, there was none issued centrally,[135] where Traditionalism was represented by the competitive Integrist newspaper, El Siglo Futuro. Already in 1927 Sáenz made the first call to collect money;[136] in 1928 he became treasurer of Obra de El Correo Español.[137] The campaign bore fruit in 1929, when the first issue of El Cruzado Español hit the streets, though it was not a daily but a weekly.[138] Officially it was launched by Circulo Jaimista de Madrid,[139] yet as it was Sáenz its owner,[140] it seems the periodical was funded mostly by his own money. Perhaps in recognition of his efforts, in 1929 he replaced Emilio Deán Berro as Jefe Regional of New Castile, the region which at the time comprised Madrid;[141] he modestly referred to himself as "la pobre persona elegida por el Augusto Jefe".[142]

Jefe Regional (1929-1932)

In 1930 Sáenz went on as the leader of Castilla La Nueva,[143] taking part in meetings,[144] making statements[145] or acting as honorary president of local circulos.[146] In May 1930 as member of Junta Nacional he co-signed a grand manifesto, which specified political vision for Spain.[147] However, following the advent of the republic his position of a party patriarch started to change; scholars point to the Integrist and the Mellist question as the motive. When facing militant republican course, both factions were driven closer to the Jaimistas and in mid-1931 they seemed on the path towards a re-unification. Sáenz, who for decades acted as icon of loyalty and held a grudge against both currents, was getting increasingly upset.[148] Another issue might have been the question of daily newspaper. In May Don Jaime wrote to the party leader Villores and to Sáenz about possibly resurrecting El Correo Español.[149] Sáenz did not enter Comisión Gestora, entrusted with the task;[150] reasons are not entirely clear, though he might have been embittered having invested own money in El Cruzado 2 years earlier.[151]

Following death of Don Jaime and assumption of the claim by Don Alfonso Carlos,[152] always somewhat sympathetic towards Integrismo, the idea of resurrecting El Correo was dropped in favor of making El Siglo Futuro, which was brought back as a dowry by the re-united Integristas, the new Carlist mouthpiece. For Sáenz it was a blow; he had systematically barred any offshoots from El Cruzado,[153] which posed as "portavoz de la ortodoxia jaimista".[154] Though in 1932 El Cruzado turned from weekly to bi-weekly[155] and changed its sub-title from "semanario defensor de la Comunión Católico-Monárquica" to "Dios, Patria, Rey", it found itself sort of sidetracked. However, following earlier bitter hostility, in 1931-32 relations between El Cruzado and El Siglo were re-formatted as "coexistencia pacífica".[156]

In 1932 Don Alfonso Carlos nominated the new Junta Suprema, which mostly confirmed appointments of Don Jaime. Sáenz remained Jefe Regional of New Castile.[157] To much surprise, he did not accept the nomination and quoting health reasons[158] he resigned all 3 functions: co-president of Junta Suprema,[159] president of its comisión ejecutiva, and Jefe Regional of New Castile.[160] Historians claim that the decision was due to two factors. One was Sáenz's fundamental hostility towards the Integristas and the Mellistas, not only re-admitted but assuming high positions in the united organization, Comunión Tradicionalista.[161] Another was his rancor towards a would-be reconciliation with the Alfonsists, advanced by leaders like Rodezno and Oriol[162] and - or at least it might have seemed so - by Don Alfonso Carlos himself. Though Sáenz was not among the most militant opponents of a dynastic agreement,[163] the party leader Villores was advised caution as to him.[164] Eventually in 1932 Junta Suprema declared that El Cruzado did not represent Traditionalist orthodoxy.[165] Some scholars claim that at this point the Cruzadistas were expulsed from the Comunión,[166] but others maintain they were merely disauthorised.[167]

Last years (1932-1939)

Following disauthorisation of El Cruzado the Cruzadistas formed a group named Núcleo de la Lealtad.[168] Some historians claim that it was run by "cuadrilátero dirigente", which apart from Sáenz consisted of Izaga, Pérez Najera and Arana,[169] others maintain that "this small but noisy faction", which failed "to attract much popular support", was led Sáenz and Jesús Cora y Lira.[170] Instead of a dynastic accord with the Alfonsinos, they fiercely advocated that Don Alfonso Carlos - octogenarian and with no descendancy - appoints his successor. The claimant preferred not to burn the bridges and in mid-1932 he met the Cruzadistas in Toulouse.[171] It is not clear whether Sáenz was present, yet it was his motion that was declared as allegedly adopted by so-called Asamblea de Tolouse;[172] it claimed that if nomination of a successor does not take place, Don Alfonso Carlos organizes a grand assembly, which in turn would determine who the next king would be.[173]

In 1933 Don Alfonso Carlos kept exchanging personal letters with Sáenz.[174] Maintaining very correct tone and commencing with "mi querido Don Lorenzo Sáenz",[175] the claimant nevertheless tried to convince the addressees that they should remain fully loyal, even in case he decides to seek understanding with the deposed Alfonso XIII;[176] he also demanded that El Cruzado ceases its somewhat rebellious campaign.[177] In a letter to the new Carlist political leader Rodezno he preferred not to resort to ultimate measures and declared that "son, pues, ellos así como cuantos les secundan, quienes dan el paso que les separa de nuestro Partido y no yo el que los hecha".[178] Following sort of stand-off, in 1935 the Cruzadistas organized a grand assembly themselves; it materialized as so-called Asamblea de Zaragoza.[179] The rally was presided by Sáenz. Its outcome was a manifesto, which declared archduke Karl Pius the next Carlist king[180] and commenced the current known as Carloctavismo. Don Alfonso Carlos promptly disauthorised the gathering and its participants.[181]

The wartime fate of Sáenz remains a mystery. It is not known whether the coup surprised him in one of his residences (Jaén, Madrid, Llanes). He is not mentioned in works dealing with the civil war in Jaén,[182] Madrid[183] or Asturias.[184] In August 1936 a Santander-based newspaper published a note about concealed firearms, reportedly discovered by Republican security in Palacio Sinforiano in Llanes, "que ha venido occupando su pariente don Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernandez-Cortina, con residencia in Madrid", yet there was no news about him having been prosecuted.[185] In June 1938, when Asturias was already under the Nationalist control, the Llanos municipal judge was dealing with some financial claims involving Sáenz, and referred to him as "residente en la Ciudad de Jaén, zona roja".[186] Though after the war numerous newspapers published horror accounts by people who survived in the republican zone, no such recollections of Sáenz have surfaced. It is not clear why after the war he emerged in Jaén,[187] and whether wartime fate contributed to his death 6 months after the conflict ended.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ his name might come in different versions. In historiography it appears as "Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández de la Cortina" (José Luis Agudín Menéndez, El Siglo Futuro. Un diario carlista en tiempos republicanos (1931-1936), Zaragoza 2023, ISBN 9788413405667, p. 536, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol XXVIII/2, Sevilla 1959, p. 1899), "Lorenzo Sáenz Fernández Cortina" (Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820, p. 129), "Lorenzo Sáenz Fernández-Cortina" (Miguel Moreno Jara, Historia del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Jaén, Jaén 2011, p. 457, Antonio Checa Godoy, Historia de la Prensa en Jaén. 1808-2012, Jaén 2016, p. 101), "Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández" (Santiago Gallindo Herrero, Historia de los partidos monárquicos bajo la Segunda República, Madrid 1954, p. 91), "Lorenzo Sáenz Fernández" (Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714) or simply as "Lorenzo Sáenz" (Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349, pp. 72, 86-7, Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, pp. 250, 295, 305, Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, p. 283). In contemporary press he could have been referred to as "Lorezno Sáenz Fernández de Cortina" (El Debate 21.05.31, available here), while in official prints of the era he was "Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández-Cortina" (Guía oficial de España, Madrid 1914, p. 741). However, in newspapers he controlled since the 1890s till the 1930s he usually appeared as "Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández Cortina", and this is the version adopted here, even though technically it is incorrect (in line with standard convention, it should be "Lorenzo Sáenz y Fernández"). Also, his surname and in particular his primero apellido might have been mis-spelled in the press as "Sáez" (e.g. La Fe 29.05.90, available here), or "Sanz" (e.g. Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 02.02.12, available here)

- ^ Manuel Sáenz García (sr) entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ in the early 19th century banking in Jaén was principally small family credit or savings unions; one of the key institutions was run by Anselmo García Rubio, though his business was heavily affected by the Peninsular War. In 1821 León García Rubio founded a bank, María José Vargas-Machuca, Merchant Bankers, Banking Houses and Large Banks. The Case of Jaen Province (1800-1936), [in:] Mariano Castro-Valdivia, María Vázquez-Fariñas, Pedro Pablo Ortúñez-Goicolea (eds.), Companies and Entrepreneurs in the History of Spain. Centuries Long Evolution in Business Since the 15th Century, London 2012, ISBN 9783030613174, p. 122

- ^ Manuel Sáenz García (jr) entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ one of his banks was Sáenz, Sáenz, Rivas y Compañía; from 1873 this house appeared as commissioner of the Spanish Mortgage Bank, Vargas-Machuca 2012, p. 122

- ^ one author claims 1863 and provides additional details, namely that the ceremony took place in the Jaén church of San Bartolomé, see Moreno Jara 2011, p. 56. However, the year of 1863 appears somewhat dubious, as Lorenzo was born in March 1863

- ^ Don Lope de Sosa. Crónica mensual de la provincia de Jaén 31.10.41, available here

- ^ her father was Juan Fernández Bustamante (Pendueles, 1791), her mother was Ana María Fernández Cortina (Pendueles, 1793), Moreno Jara 2011, p. 56

- ^ see e.g. Bishop Joaquín Fernández Cortina, [in:] Catholic Hierarchy service, available here

- ^ according to the standard naming convention his name was Manuel Fernandez y Fernandez-Cortina. However, for reasons which are not clear and thanks to rather loose official regulations at the time, he appeared as Manuel Fernandez Cortina, Moreno Jara 2011, p. 56

- ^ Moreno Jara 2011, p. 56

- ^ born before 1866, died 1905, El Defensor de Granada 21.04.08, Hidalguía II/4 (1954), p. 43

- ^ born 1870, died 1932. Abogado in Jaén and propietario, he married to Gertrudis de Bonilla y Bonilla, Moreno Jara 2011, p. 574

- ^ referred to as "rico propietario", he died in 1920, Don Lope de Sosa. Crónica mensual de la provincia de Jaén 01.12.20, available here

- ^ the Geneanet site here lists him as the 3rd oldest, which appears to be incorrect, as Juan was born in 1870 and Joaquín - apparently - prior to 1866

- ^ Joaquin died 1905, Manuel in 1920 and Juan in 1932

- ^ in 1908, when he was to run for the Cortes from the Navarrese district of Tudela, he was advertised as "tiene cerca del distrito la circunstancia grata de ser oriundo de la noble tierra que baña el Ebro, donde ha hecho sus estudios", El Correo Español 03.06.08, available here. Circumstances suggests that "la noble tierra que baña el Ebro" means La Rioja, separated from the merindad of Tudela by the Ebro. One author claims that Sáenz was "a veteran of the 1870-6 war", Blinkhorn 2008, p. 73. Theoretically it is not impossible, since he was 13 in 1876 and boys of this age did fight in Carlist troops, compare the case of Teodoro Mas. However, it would have been odd that this episode has never been mentioned in numerous hagiographic press notes, published on him later

- ^ Sáenz Fernández, Lorenzo entry, [in:] Pares. Portal de Archivos Españoles service, available here

- ^ Sáenz Fernández, Lorenzo entry, [in:] Pares

- ^ Moreno Jara 2011, p. 457

- ^ the exact date given is 22.05.1885, Moreno Jara 2011, p. 457

- ^ B. de Artagan, Bocetos tradicionalistas, Barcelona 1912, p. 251

- ^ Moreno Jara 2011, p. 457

- ^ La Opinión de Asturias 14.03.1893, available here. It is not clear why the ceremony took place in Madrid, since the groom was from Jaén and the bride from Llanes

- ^ one author refers to her as "perteneciente a la oligarquía santanderina", Moreno Jara 2011, p. 457. There are numerous sources which confirm she was related to Asturias but none pointing to Cantabria

- ^ or because he knew her brother Sinforiano, as the two studied law in Universidad Central in the early 1880s. For her links to Llanes see e.g. Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 27.07.43, available here

- ^ named Maximina Sobrino Díaz; she married Sebastian Dosal, Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 27.07.43, available here

- ^ compare e.g. Guillermo Fernández, Gloria Pomarada, La casona de La Concepción, en obras para su transformación en un hotel, [in:] El Comercio 09.10.18, available here

- ^ Lorenzo Sáenz knew Sinforiano very well. Apart from years spent studying law in Central, later as brothers-in-law they attended many family events, compare e.g. El Pueblo 26.05.09, available here

- ^ Fernández, Pomarada 2018. When Sinforiano died, the estate was inherited by his sister Fernanda, and after her death by their common sister Antonia (the wife of Lorenzo). The two sisters passed away one after another, Fernanda on June 10,1933, and Antonia on August 12,1933

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 17.08.33, available here

- ^ Fernández, Pomarada 2018

- ^ no later than in 1900, Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 10.09.00, available here

- ^ at Plaza de las Cortes 8, La lid católica 05.07.93, available here. The appartment would remain his residence until his death

- ^ "sin sucesión", see Certificado de defunción Lorenzo Sáenz, available here

- ^ Lorenzo's sister-in-law (sister to his wife), Fernanda Dosal Sobrino, married conde Mendoza Cortina, see e.g. El Debate 11.06.33, available here. Hence Sáenz and condesa (consorte) de Mendoza Cortina were hermanos políticos, see e.g. El Lábaro 17.08.17, available here

- ^ Hidalguía II/4 (1954), p. 43

- ^ in 1897, compare Joaquín Sáenz Fernández entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ El Baluarte 08.05.96, available here

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, p. 79

- ^ "una conspiración íntegro-conservadora, ha dejado de publicarse en Jaén el interesante periódico El Norte Andaluz, que ha venido prestando valiosos servicios a la causa católica", quoted after Checa Godoy 2016, p. 70. In 1893 an Integrist periodical, El Pueblo Católico, managed by Francisco Ureña Navas, appeared in Jaen

- ^ it was launched in 1893 and remained published until 1935, Checa Godoy 2016, p. 79

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, pp. 69-70

- ^ El Norte Andaluz 30.03.89, available here

- ^ El Norte Andaluz 20.09.90, available here

- ^ La Unión Católica 09.05.80, available here

- ^ its presidente efectivo was Eusebio Sánchez Pérez, El Correo Español 27.04.95, available here

- ^ La Voz de Granada 11.05.95, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 04.05.96, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 21.01.97, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 29.03.98, available here

- ^ Guía Oficial de España 1892, available here

- ^ Saénz edited and published Memorias militares by Miguel Gómez, manuscript account of his raid during the First Carlist War in 1836, available online courtesy of Biblioteca Navarra Digital here. However, the work was published in 1914. Perhaps Sáenz completed the edition in the early 1890s and this was the basis of his admission to RAH, yet it remains pure speculation. There is no other Sáenz's work known which might have gained him entry to RAH

- ^ La Opinion de Asturias 14.03.98, available here

- ^ Moreno Jara 2011, p. 457

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, p. 94

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, p. 101

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, p. 79

- ^ El Correo Español' 31.10.96, available here

- ^ the presidency went to Conde de Casasola, El Correo Español 14.12.96, available here

- ^ at that time the president was Cesareo Sanz Escartín, El Imparcial 15.12.98, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 23.06.96, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 25.04.98, available here

- ^ or at least was a member of the Madrid Colegio de Abogados, Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 10.09.00, available here, for 1903 see El Universo 30.09.03, available here

- ^ El Dia de Palencia 04.06.08, available here

- ^ e.g. since 1915 together with brothers he owned fábrica de aceites La Rosa in Jaén, Patrimonio industrial, agrícola, ganadero o comer, Patrimonio Perdido, [in:] RedJaen service, available here

- ^ Jurisprudencia civil. Colección completa de las sentencias dictadas por el Tribunal Supremo ..., Madrid 1921, p. 413. For details and photos, see Central Hidroeléctrica de San Rafael, [in:] RedJaen service, available here

- ^ where he had "residencia temporal", Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 18.05.00, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 21.11.03, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 16.06.05, available here, also Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 17.08.06, available here

- ^ the estate comprised 64 ha, nothing special e.g. in Andalusia, but rather huge property by standards of northern Spain, see Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 02.02.12, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 23.04.07, available here

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, pp. 101-102

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, p. 102

- ^ El Correo Español 25.02.08, available here

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, pp. 101-102

- ^ Checa Godoy 2016, p. 125

- ^ the honorary president was Matías Barrio y Mier, El Correo Español 09.01.05, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 23.01.05, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 21.06.06, available here

- ^ he was endorsed by the Carlist leader in Tudela, Blas Morte, El Correo Español 10.06.08, available here

- ^ in 1908 he was advertised as "tiene cerca del distrito la circunstancia grata de ser oriundo de la noble tierra que baña el Ebro". Apparently it was an attempt to present him as almost the native of Tudela (Rioja was just across the Ebro) and divert would-be charges of being a cuckoo candidate, El Correo Español 03.06.08. available here

- ^ see his 1908 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ El Eco de Navarra 04.06.08, available here

- ^ El Cronista de Correos 25.11.08, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 27.11.08, available here

- ^ El Dia de Palencia 28.11.08, available here

- ^ in 1908 he launched a competition for Himno nacional carlista, La Verdad June 1908, available here. Unfortunately, it is not clear what opus emerged victorious, though at the time the most iconic song, Oriamendi, has just been translated from its original Basque into Spanish by Ignacio Baleztena

- ^ El Correo Español 10.11.08, available here

- ^ Froilán de Lózar, La aventura política de Matías Barrio y Mier, [in:] Publicaciones de la Institución Tello Téllez de Meneses 78 (2007), p. 196

- ^ El Correo Español 27.08.09, available here

- ^ he was among 19 Carlist candidates standing in Spain and among 5 running from in Navarre, El Correo Español 19.04.10, available here

- ^ Sebastian Cerro Guerrero, Los resultados de las elecciones de diputados a Cortes de 1910 en Navarra, [in:] Principe de Viana 49 (1988), p. 93

- ^ La Epoca 12.05.10, available here

- ^ "una serie de horróres que constituyen toda una página histórica", El Imparcial 13.05.10, available here

- ^ his opponent claimed that women, brainwashed by priests, threatened their husbands with divorce if they would not vote for Sáenz (women did not have voting rights in Spain until 1933, and divorce was legally introduced in 1932), El Imparcial 13.05.10, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 19.05.10, available here

- ^ El Imparcial 18.06.10, available here. The liberal candidae won in 12 districts, while Sáenz won in 10, including the key cities of Tudela and Corella, Cerro Guerrero 1988, p. 104

- ^ see his 1910 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 06.03.14, available here

- ^ Jesús María Fuente Langas, Las Elecciones Generales de 1914 en Navarra, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 16 (1992), p. 666. The third candidate, a Maurista, got only 127 votes

- ^ Fuente Langas 1992, p. 661

- ^ Jesús María Fuente Langas, Elecciones de 1916 en Navarra, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 51 (1990), p. 952

- ^ El Universo 12.05.09, available here

- ^ Artagan 1912, p. 251, also "ex secretario de la Jefatura delegada en tiempos de Barrio y Mier y Feliu", El Correo Español 04.12.19, available here; Barrio died in 1909

- ^ El Correo Español 21.04.09, available here

- ^ La Verdad 28.05.11, available here

- ^ for Cintruenigos 1911 see El Correo Español 09.02.11, available here, for Granada 1912 see La Verdad 21.03.12, available here

- ^ an affluent Bilbao Carlist, José Bulfy y Bengo, in his last will donated 125,000 ptas, Aurera 16.12.11, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 05.12.19, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 11.03.12, available here

- ^ Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012, p. 444, Melchor Ferrer, Breve historia del legitimismo español, Sevilla 1958, p. 97

- ^ El Correo Español 17.10.13, available here

- ^ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 458

- ^ Sáenz was not among the protagonists of the conflict; the related monograph mentions him only once, compare Andrés Martín 2000

- ^ Ferrer 1959 , pp. 101-102, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 129

- ^ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 129

- ^ details in Andrés Martín 2000, pp. 139-186

- ^ Ferrer 1959, p. 113

- ^ El Correo Español 03.12.19, available here

- ^ La Epoca 03.12.19, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 05.02.20, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 11.09.19, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 13.04.20, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 28.07.20, available here

- ^ La Verdad 19.07.29, available here

- ^ El Debate 01.12.21, available here

- ^ La Verdad 10.05.23, available here

- ^ Correo de Mallorca 14.01.21, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 11.03.21, available here

- ^ La Verdad 21.03.24, available here

- ^ La Verdad 12.08.26, available here

- ^ El Cantabrico 02.12.26, available here, also La Epoca 20.12.28, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 19.01.26, available here. He was in conflict with the Llanes ayuntamiento over financial duties, El Cantabrico 19.01.27, available here. Llanes was his "residencia veraniega", El Cruzado Español 02.08.29, available here

- ^ there was a Carlist periodical issued in Madrid by Luis Hernando de Larramendi, named Criterio, though it was not a daily but a weekly, its circulation was limited, and it adhered to somewhat elitist, intellectual format, Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 211

- ^ La Verdad 21.11.27, available here

- ^ La Verdad 19.07.28, available here

- ^ its chief editor was Guillermo Arsenio de Izaga, "hombre-orquestra de El Cruzado", opinion of Eduardo Gonzalez Calleja referred after Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 215

- ^ Manuel de Santa Cruz (Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta), Apuntes y documentos para la historia del tradicionalismo español: 1939–1966, vol. 3, Sevilla 1979, p. 27

- ^ "su fundador, seguramente propietario", Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 215, and "sería también Lorenzo Sáenz su propietario", José Luis Agudín Menéndez, En busca del diario perdido. El (Bi) semanario "El Cruzado Español" en la reconstrucción propagandística y organizativa del carlismo (1929-1932), [from now onwards as Agudín Menéndez 2023b, in:] Historia contemporánea 72 (2023), p. 440

- ^ El dia grafico 26.04.29, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 25.07.29, available here

- ^ when absent, e.g. in Jaén, his replacement caretaker was Pedro Ruiz de Apodaca y Arzu, El Cruzado Español 15.08.30, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 11.04.30, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 02.08.29, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 16.05.30, available here

- ^ it included e.g. the concept of "la España federativa", El Cruzado Español 23.05.30, available here

- ^ compare e.g. Agudín Menéndez 2023, pp. 222-223, Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 86-87

- ^ Román Oyarzun, Historia del Carlismo, Madrid 1944, p. 456

- ^ Agudín Menéndez 2023b, p. 449

- ^ none of the sources consulted clarifies the issue. In particular, it remains unknown why Don Jaime, who had no specific reason to be unhappy about El Cruzado Español, tried to re-launch El Correo Español. Perhaps he was somewhat uneasy that El Cruzado was Sáenz's personal property, which from the party point of view reduced it steerability, and intended to have a party-owned daily. Perhaps he was influenced by some Integristas and Mellistas, who wanted to build a new daily of united Traditionalism

- ^ initially Sáenz maintained perfectly good relations with the claimant, e.g. when in 1931 discussing names of new post-fusion circulos, Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054, p. 57

- ^ as Sáenz was militantly averse towards the Integrists and the Mellists, he did not admit people like Peñaflor or Claro Abanades to any co-operation with El Cruzado; by the same token, he held a grudge against his former El Correo Español colleague Gustavo Sánchez Márquez, who made a pro-Mellista turn during last years of El Correo, Agudín Menéndez 2023b, pp. 442-443

- ^ Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 217

- ^ it was issued on Fridays and Tuesdays

- ^ Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 217

- ^ there was no jefe regional appointed for the entire Andalusia. Andalucía occidental was headed by Manuel Fal Conde, yet there was no leader appointed for Andalucia oriental; instead, there were merely jefes provinciales. The one for the province of Jaén was Fernando Contreras, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 73, Moral Roncal 2009, p. 78

- ^ literally he admitted to "carecer de fuerzas de todo género— escasísima la vista y achacosa la salud general de mi ya viejo y cansado organismo", El Siglo Futuro 24.02.32, available here

- ^ the issue is somewhat unclear. The nomination listed him first in sequence among all members nominated, but there was no mention about presidency, compare El Siglo Futuro 20.02.32, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 05.04.32, available here

- ^ Moral Roncal 2009, p. 80

- ^ Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX, Sevilla 1979, p. 33, Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 295

- ^ e.g. on February 16, 1932 some 10 Cruzadistas signed a polite, yet ultimative letter to Don Alfonso Carlos, demanding appointment of the successor. The signatories included people like Najera and Deán, but Sáenz was not among them, Ferrer 1979, p. 43

- ^ Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 222. It remains somewhat of a paradox that Manuel Senante, until 1931 among leaders of the breakaway Integrists, in 1932 denounced Sáenz as a potential rebel in a letter to Villores

- ^ Agudín Menéndez 2023, p. 223

- ^ Cristina Barreiro Gordillo, El carlismo y su red de prensa en la Segunda República, Madrid 2003, ISBN 9788497390378, p. 41

- ^ "the National Junta deprived El Cruzado Español of official recognition and threatened the grumblers with expulsion from the Communion", Blinkhorn 2008, p. 86

- ^ Ferrer 1979, vol. XXX, p. 70. Many authors from the onset, i.e. from the early 1931, refer to Cruzadistas and to Nucleo de la Lealtad, see e.g. Santa Cruz 1979 vol. 3, pp. 26–27

- ^ Agudín Menéndez 2023b, p. 441

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 86-87

- ^ El Cruzado Español 14.06.32, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 09.08.23, available here

- ^ “la Comunión Tradicionalista se propone con todas sus fuerzas, no sólo elevar al trono tradicional de sus mayores al monarca legítimo, al augusto señor don Alfonso Carlos I de Borbón y de Austria-Este, sino designar a su debido sucesor según las leyes y procedimientos tradicionales" and " si las circunstancias actuales se prolongasen con la pasividad impuesta hasta este instante, el augusto Caudillo se dignará modificar las normas que regulan el funcionamiento de las cortes generales, convocando expresamente a magna asamblea a todos los organismos, entidades y personalidades de la Causa para que aborden, sin mayores dilaciones, la gran cuestión sucesoria en el trono tradicional español", quoted after Francisco de las Heras y Borrero, Un pretendiente desconocido. Carlos de Habsburgo. El otro candidato de Franco, Madrid 2004, ISBN 8497725565, p. 35

- ^ Melchor Ferrer (ed.), Antologia de los documentos reales de la dinastía carlista, Madrid 1951, p. 181, also Juan-Cruz Allí Aranguren, El carlismo de Franco. De Rodezno a Carlos VIII [PhD thesis UNED], s.l. 2021, p. 718

- ^ all letters are reproduced in Heras y Borrero 2004, pp. 172-179

- ^ e.g. Don Alfonso Carlos argued that (letter dated May 12, 1933) that if one admits that Carlos VII was in his own right when deciding on exclusion of Alfonso's branch, then by the same token one should admit the right of Jaime III to recognize Don Juan, Ferrer 1979, p. 36

- ^ Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX/I, Sevilla 1979, p. 70

- ^ Heras y Borrero 2004, p. 39, also Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX/II, Sevilla 1979, p. 28. Some authors claim that at this point, Don Alfonso Carlos expulsed the Cruzadistas, Jacek Bartyzel, Tradycjonalizm bez kompromisu, Radzymin-Warszawa 2023, ISBN 9788366480605, p. 754

- ^ according the leaders of the rally, the asamblea represented 30,000 Carlists

- ^ the text of the motion published in the press in 1935 and adopted by the assembly mentioned "nuestra inclinación hacia el Archiduque Don Carlos", quoted fater Santa Cruz 1979, p. 29. Similar interpretation in Canal 2000, p. 319. Another author prefers to stress that the assembly declared doña Blanca, the mother of Karl Pius, the "heiress", Blinkhorn 2008, p. 216

- ^ "resultó estéril como toda aquella labor", Ferrer 1979, vol. XXX/I, p. 116. Also "Los cruzadistas, más preocupados por la cuestión sucesoria, celebraron una asamblea en Zaragoza, afirmándose en su posición favorable a don Carlos de Habsburgo", Ferrer 1958, p. 119

- ^ Sáenz is not mentioned a single time in Luis Garrido González, Jaén y la Guerra Civil (1936-1939), [in:] Boletín del Instituto de Estudios Giennenses 198 (2008), pp. 197-226, Francisco Cobo Romero, La guerra civil y la represión franquista en la provincia de Jaén (1936-1950), Jaén 2009, ISBN 9788487115219

- ^ not a single note on Sáenz in Julius Ruiz, The ‘Red Terror’ and the Spanish Civil War. Revolutionary violence in Madrid, Cambridge 2014, ISBN 9781107054547, Rafael Casas de la Vega, El Terror. Madrid 1936, Toledo 1994, ISBN 9788488787040, Cesar Vidal, Checas de Madrid, Barcelona 2004, ISBN 9788497931687

- ^ Sáenz is missing in Pedro Luis Alonso García, La justicia republicana en Asturias. La actuación del Tribunal Popular Provincial y otros organismos jurídicos especiales durante la guerra civil (1936-1937), PhD thesis Universidad de Oviedo], Oviedo 2016, and in commercial version of the work, see Pedro Luis Alonso García, Contra rebeldes, traidores y espías: La justicia republicana en Asturias durante la Guerra Civil (1936-1937), Oviedo 2021, ISBN 9788412393231

- ^ El Cantabrico 26.08.36, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Oviedo 21.06.38, available here

- ^ and not in Madrid, his pre-war primary residence, compare his death certificate, available here

Further reading

- José Luis Agudín Menéndez, En busca del diario perdido. El (Bi) semanario "El Cruzado Español" en la reconstrucción propagandística y organizativa del carlismo (1929-1932), [in:] Historia contemporánea 72 (2023), pp. 431-462

- Cristina Barreiro Gordillo, El carlismo y su red de prensa en la Segunda República, Madrid 2003, ISBN 9788497390378

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349

- Sebastian Cerro Guerrero, Los resultados de las elecciones de diputados a Cortes de 1910 en Navarra, [in:] Principe de Viana 49 (1988), pp. 93-106

- Antonio Checa Godoy, Historia de la Prensa en Jaén. 1808-2012, Jaén 2016

- Jesús María Fuente Langas, Las Elecciones Generales de 1914 en Navarra, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 16 (1992), pp. 655-666