Rishabhanatha

| Tirthankara Rishabhanatha | |

|---|---|

1st Tirthankara | |

| |

| Other names | Ādinātha, Ādeśvara (the first conqueror), Ādarśa Puruṣa (perfect man), Ikṣvāku |

| Venerated in | Jainism |

| Predecessor | Sampratti (last Tirthankara of the previous time-cycle) |

| Successor | Ajitanatha |

| Mantra | Oṃ Ṛṣabhadeva Namaḥ Oṃ Śrī Ādināthāya Namaḥ |

| Symbol | Bull |

| Height | 500 dhanuṣ (1,500 meters)[1] |

| Age | 8.4 million purvas (592.704 x 1018 years)[1][2][3] |

| Tree | Banyan |

| Color | Golden |

| Texts | Ādi purāṇa Mahāpurāṇa Bhaktāmara Stotra |

| Gender | Male |

| Festivals | Akshaya Tritiya |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | Ṛṣabha |

| Died | |

| Parents | |

| Spouse | Sumangalā/Yaśasvatī Sunandā/Nandā [4][5] |

| Children | • 100 sons (including: Chakravarti Bharata, Prince Nami, and Kamadeva Bahubali) • 2 daughters: Brāhmī and Sundarī (Mahasatis) Reference:[6] |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Rishabhanatha (Devanagari: ऋषभनाथ), also Rishabhadeva (Devanagari: ऋषभदेव, Ṛṣabhadeva), Rishabha (Devanagari: ऋषभ, Ṛṣabha) or Ikshvaku (Devanagari: इक्ष्वाकु, Ikṣvāku), is the first tirthankara (Supreme preacher) of Jainism.[7][8] He was the first of twenty-four teachers in the present half-cycle of time in Jain cosmology and called a "ford maker" because his teachings helped one cross the sea of interminable rebirths and deaths. The legends depict him as having lived millions of years ago. He was the spiritual successor of Sampratti Bhagwan, the last Tirthankara of the previous time cycle.[6][9] He is also known as Ādinātha (lit. "first Lord"),[9] as well as Adishvara (first Jina), Yugadideva (first deva of the yuga), Prathamarajeshwara (first God-king) and Nabheya (son of Nabhi).[10][11] He is also known as Ikshvaku, establisher of the Ikshvaku dynasty. Along with Mahavira, Parshvanath, Neminath, and Shantinath, Rishabhanatha is one of the five Tirthankaras that attract the most devotional worship among the Jains.[12]

According to traditional accounts, he was born to king Nabhi and queen Marudevi in the north Indian city of Ayodhya, also called Vinita.[6] He had two wives, Sumangalā and Sunandā. Sumangalā is described as the mother of his ninety-nine sons (including Bharata) and one daughter, Brahmi. Sunandā is depicted as the mother of Bahubali and Sundari. The sudden death of Nilanjana, one of the dancers sent by Indra in his courtroom, reminded him of the world's transitory nature, and he developed a desire for renunciation.

After his renunciation, the legends as described in major Jain texts such as Hemachandra's Trishashti-Shalakapurusha-Charitra and Adinathcharitra written by Acharya Vardhamansuri state Rishabhanatha travelled without food for 400 days.[13][14][15] The day on which he got his first ahara (food) is celebrated by Jains as Akshaya Tritiya. In devotion to Rishabhanatha, Śvetāmbara Jains perform a 400-day-long fast, in which they consume food on alternating days. This religious practice is known as Varshitap. The fast is broken on Akshaya Tritiya.[16][17] He attained Moksha on Mount Ashtapada. The text Adi Purana by Jinasena, Aadesvarcharitra within the Trishashti-Shalakapurusha-Charitra by Hemachandra are accounts of the events of his life and teachings. His iconography includes ancient idols such as at Kulpak Tirth and Palitana temples as well as colossal statues such as Statue of Ahimsa, Bawangaja and those erected in Gopachal hill. His icons include the eponymous bull as his emblem, the Nyagrodha tree, Gomukha (bull-faced) Yaksha, and Chakreshvari Yakshi.

Life

Rishabhanatha is known by many names including Adinatha, Adishwara, Yugadeva and Nabheya.[10] Ādi purāṇa, a major Jain text records the life accounts of Rishabhanatha as well as ten previous incarnations according to the Digambara tradition.[18] For Rishabhanatha's biography in accordance with the Śvetāmbara tradition is found in several texts such as Hemachandra's Trishashti-Shalakapurusha-Charitra and Adinathcharitra written by Acharya Vardhamansuri.[15] Jain tradition associates the life of a tirthankara to five auspicious events called the pancha kalyanaka. These include garbha (mother's pregnancy), janma (birth), diksha (initiation), kevalyagyana (omniscience) and moksha (liberation).[2][19][20]

According to Jain cosmology, the universe does not have a temporal beginning or end. Its "Universal History"[21] divides the cycle of time into two halves (avasarpiṇī and utsarpiṇī) with six aras (spokes) in each half, and the cycles keep repeating perpetually. Twenty-four Tirthankaras appear in every half, the first Tirthankara founding Jainism each time after the destruction of dharma at the end of each half cycle of time. This is similar to, but not completely the same as the idea of destruction of dharma at the end of Kali Yuga in Hindu mythology. In the present time cycle, Rishabhanatha is credited as being the first tīrthaṅkara. Usually, all the tīrthaṅkaras are born in the fourth spoke of the half cycle. However, Rishabhanatha is an exception as he was born at the end of the third half (known as sukhamā-dukhamā erā).[4][22][23]

Rishabhanatha is said to be the founder of Jainism in the present Avsarpini (a time cycle) by all sub-traditions and sects of Jainism.[4][8] Jain chronology places Rishabhanatha in historical terms, as someone who lived millions of years ago.[6][9][24] He is believed to have been born 10224 years ago and lived for a span of 8,400,000 purva (592.704 × 1018 years).[1][2] His height is described in the Jain texts to be 500 bows (1312 ells), or about 4920 feet/1500 meters.[1] Such descriptions of non-human heights and age are also found for the next 21 Tirthankaras in Jain texts and according to Kristi Wiley – a scholar at University of California Berkeley known for her publications on Jainism. Most Indologists and scholars consider all the first 22 of 24 Tirthankaras to be prehistorical,[25] or historical and a part of Jain mythology.[1][26] However, among Jain writers and some Indian scholars, some of the first 22 Tirthankaras are considered to reflect historical figures, with a few conceding that the inflated biographical statistics are mythical.[27]

According to Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, a professor of comparative religions and philosophy at Oxford who later became the second President of India, there is evidence to show that Rishabhdeva was being worshipped by the first century BCE. The Yajurveda[a] mentions the names of three Tirthankaras – Rishabha, Ajitanatha and Arishtanemi, states Radhakrishnan, and "the Bhāgavata Purāṇa endorses the view that Rishabha was the founder of Jainism".[28]

Birth

Rishabhanatha was born to Nabhi and Marudevi, the king and queen of Ayodhya, on the ninth day of the dark half of the month of Chaitra (caitra krişna navamĩ).[4][29][30] His association to Ayodhya makes it a sacred town for Jains, as it is in Hinduism for the birth of Rama.[6] In Jain tradition, the birth of a tirthankara is marked by 14 auspicious dreams of the mother. These are believed to have been seen by Marudevi on the second day of Ashadha (a month of the Jain calendar) krishna (the new moon). The dreams signified the birth of a chakravartin or a tirthankara, according to the supposed explanation by Indra to Marudevi.[31]

Marriage and children

Rishabhanatha is believed to have had two wives, Sunanda and Sumangala.[4][32] Sumangala is claimed to be the mother of ninety-nine sons (including Bharata) and one daughter, Brahmi.[4][33] Sunanda is believed to be the mother of Bahubali and Sundari.[10] Jain texts state that Rishabhanatha taught his daughters Brahmi and Sundari, Brahmi script and the science of numbers (Ank-Vidya) respectively.[4] The Pannavana Sutra (2nd century BCE) and the Samavayanga Sutra (3rd century BCE) of the aagams followed by the Śvetāmbaras list many other writing scripts known to the ancient Jain tradition, of which the Brahmi script named after Rishabha's daughter tops the list.[34] His eldest son, Bharata, is stated to have ruled ancient India from his capital of Ayodhya.[35] He is described as a just and kind ruler in Jain texts, who was not attached to wealth or vices.[36]

Rule, administration and teachings

Rishabhanatha was born in bhoga-bhumi or the age of omnipresent happiness.[4][21][37] It is further suggested that no one had to work because of miraculous wish-fulfilling trees called the kalpavrikshas.[4][21][37] It is stated that people approached the king for help due to decreased efficacy of the trees with passage of time.[4][21][38] Rishabhanatha is then said to have taught them six main professions. These were: (1) Asi (swordsmanship for protection), (2) Masi (writing skills), (3) Krishi (agriculture), (4) Vidya (knowledge), (5) Vanijya (trade and commerce) and (6) Shilp (crafts).[39][40][41] In other words, he is credited with introducing karma-bhumi (the age of action) by founding arts and professions to enable householders to sustain themselves.[21][42][43] Rishabhanatha is credited in Jainism to have invented and taught fire, cooking and all the skills needed for human beings to live. In total, Rishabhanatha is said to have taught seventy-two sciences to men and sixty-four to women.[6] The institution of marriage is stated to have come into existence after his marriage to Sunanda marked the precedence.[4][42] According to Paul Dundas, Rishabhanatha, in Jainism, is thus not merely a spiritual teacher, but the one who founded knowledge in its various forms.[21] He is depicted as a form of culture hero for the current cosmological cycle.[21]

Traditional sources state that Rishabhanatha was the first king who established his capital at Vinitanagara (Ayodhya).[39] He is claimed to have given first laws for governance by a king.[39] He is said to have established the three-fold varna system based on professions consisting of kshatriyas (warriors), vaishyas (merchants) and shudras (artisans).[21][39][44] Bharata is said to have added the fourth varna, brahmin to the system.[45]

Renunciation

Jain legends talk about a dance of celestial dancers organised in Rishabhanatha's royal assembly hall by Indra, the heavenly-king of the first heaven.[46] Nilanjana, one of the dancers, is said to have died in midst of the series of vigorous dance movements.[45][47][48] The sudden death of Nilanjana is said to have reminded Rishabhanatha of the world's transitory nature, triggering him to renounce his kingdom, family and material wealth.[45][46][49] He is then believed to have distributed his kingdom among his hundred sons.[45] Bharata supposedly got the city of Ayodhya and Bahubali is believed to have got the city of Taxila and the kingdom of Gandhara (as per the Śvetāmbara tradition)[50][51][52] or Podanapur (as per the Digambara tradition).[45][48] He is believed to have become a monk in Siddharta-garden, in the outskirts of Ayodhya, under Ashoka tree on the ninth day of the month of Chaitra Krishna (Hindu calendar).[45] Tirthankaras usually tear out five handfuls of their hair at initiation. Śvetāmbara text Trisasti-salaka-purusa-caritra mentions Rishabhanatha tore only four handfuls of his hair. Just as the moment he was about to pull and tear a fifth handful, Indra requested him not to do so, because the remaining hair 'shone like emerald on his golden soulders'.[53]

Akshaya Tritiya

Jains believe that people did not know the procedure to offer food to a monk, since Rishabhanatha was the first one.[54][55] His great-grandson, Shreyansa, a king of Gajapura (now Hastinapur) after recalling his previous birth in which he had offered food to a Jain monk keeping in mind all the dietary restrictions and preparing it to be free from all faults, offered him sugarcane juice (ikshu-rasa) with required procedure to break 400-days-long fast.[55][56] Jains celebrate the event as Akshaya tritiya every year on the third day of the bright fortnight of the month Vaishaka (usually April).[55][57] It is believed to be the starting of the ritual of ahara-daana (food offerings) from layperson to mendicants.[21]

Omniscience

Rishabhanatha is said to have spent a thousand years performing austerities before attaining kevala jnana (omniscience) under a banyan tree in the town of Purimatla[58] on the 11th day of falgun-krishna (a month in traditional calendar) after destroying all four of his ghati-karma.[6][55][59] The Devas (heavenly beings) are suggested to have created divine preaching halls known as samavasaranas for him after that.[2] He is believed to have given the five major vows for monks and 12 minor vows for laity.[60] He is believed to have established the sangha (four-fold religious order) consisting of male and female mendicants and disciples.[2][61] His religious order is mentioned in Kalpa Sutra to have consisted of 84,000 sadhus (male monks) and 3,000,000 sadhvis (female monks).[62]

- Ancient footprints of lord Rishabha commemorating the place of his Omniscience

- New shrine built to protect the ancient footprints

- Jaina monks & devotees paying homage to the lord Rishabha

Nirvana kalyanaka

Rishabhanatha is said to have preached the principles of Jainism far and wide.[61][63] He is suggested to have attained Nirvana or moksha, destroying all four of his aghati-karma.[64] This is marked as liberation of his soul from the endless cycle of rebirths to stay eternally at siddhaloka. His death is believed in Jainism to have occurred on Ashtapada (also known as Mount Kailash) on the fourteenth day of Magha Krishna (Hindu Calendar).[63][65][66] His total age at that time is suggested to be 84 lakh purva years, with three years and eight and a half months remaining of the third era.[49] According to medieval era Jain texts, Rishabhanatha performed asceticism for millions of years, then returned to Ashtapada where he fasted and performing inner meditation to his moksha. They further state that Indra came with his fellow gods from the heavens after that, to perform rituals of the place from where Rishabhanatha attained moksha.[67]

In literature

The Ādi purāṇa, a 9th-century Sanskrit poem,[18] and a 10th-century Kannada language commentary on it by the poet Adikavi Pampa (fl. 941 CE), written in Champu style, a mix of prose and verse and spread over sixteen cantos, deals with the ten lives of Rishabhanatha and his two sons.[68][69] In 11th century, Śvetāmbara monk Acharya Vardhamansuri wrote Adinathcharit, an 11000-verse-long biography of Rishabhanatha in Prakrit. The life of Lord Rishabhanatha is also detailed in Mahapurana of Jinasena, Trisasti-salaka-purusa-caritra by the Śvetāmbara monk Acharya Hemachandra, Kalpa Sutra (a Śvetāmbara Jain text written by Bhadrabāhu that contains the biographies of some of the Tirthankaras), and Jambudvipa-prajnapti.[70][71] Bhaktamara Stotra by Acharya Manatunga is one of the most prominent prayers mentioning Rishabhanatha.[72] There is mention of Rishabha in Hindu texts, such as in the Rigveda, Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana (in 5th canto).[73][74] In later texts, such as the Bhagavatapurana, he is described as an avatar of Vishnu, a great sage, known for his learning and austerities.[70][75] Rishabhanatha is also mentioned in Buddhist literature. It speaks of several tirthankara and includes Rishabhanatha along with: Padmaprabha, Chandraprabha, Pushpadanta, Vimalanatha, Dharmanatha, and Neminatha. A Buddhist scripture named Dharmottarapradipa mentions Rishabhanatha as an Apta (Tirthankara).[33]

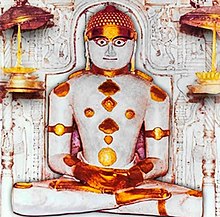

Iconography

Rishabhanatha is usually depicted in the lotus position or kayotsarga, a standing posture of meditation. The distinguishing features of Rishabhanatha are his long locks of hair which fall on his shoulders, and an image of a bull in sculptures of him.[76] In accordance with the Śvetāmbara tradition, almost all idols depicting Rishabhanatha have hairlocks on both his shoulders, in accordance with the mention of a loch (tearing out of hair) with four handfuls instead of the normal five handfuls in Trisasti-salaka-purusa-caritra, which makes his iconography distinctive from other Tirthankaras'.[53] Most of his iconography as per the beliefs of the Śvetāmbara tradition can be found at Palitana temples. Rishabhanatha's hairlocks have been depicted in first century CE sculptures found in Mathura and Causa.[77] Paintings of him usually depict legendary events of his life. Some of these include his marriage, and Indra performing a ritual known as abhisheka (consecration). He is sometimes shown presenting a bowl to his followers and teaching them the art of pottery, painting a house, or weaving textiles. The visit of his mother Marudevi is also shown extensively in painting.[78] He is also associated with his Bull emblem, the Nyagrodha tree, Gomukha (bull-faced) Yaksha, and Chakreshvari Yakshi.[79]

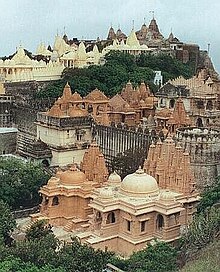

Statue of Ahimsa, carved out of a single rock, is a 108 feet (33 m) tall (121 feet (37 m) including pedestal) statue of Rishabhanatha and is 1,840 sq feet in size. It is said to be the world's tallest Jain idol.[80] It is located 4,343 feet (1,324 m) above from sea level, at Mangi-Tungi hills near Nashik (Maharashtra). Officials from the Guinness Book of World Records visited Mangi Tungi and awarded the engineer of the 108 ft tall Rishabhdeva statue, C R Patil, the official certificate for the world's tallest Jain idol.[81][82] In 2016, a 108 feet idol of Rishabhnatha (Adinatha) was installed at Palitana.[83]

In Madhya Pradesh, there is the Bawangaja (meaning 52 yards (156 ft)) hill, near Barwani with a Gommateshvara figure covered on the top of it. This site is important to Jain pilgrims particularly on the full moon day in January.[84] The site has a Rishabanatha statue carved from a volcanic rock.[85] The 58.4 feet (17.8 m) Rishabhanatha Statue at Gopachal Hill, Gwalior Fort, Madhya Pradesh. Thousands of Jain idols including 58.4 foot idol of Rishabhanatha were carved in the Gopachal Hill idol from 1398 CE to 1536 CE by rulers of Tomar dynasty rulers – Viramdev, Dungar Singh and Kirti Singh.[86] A 43 feet (13 m) statue of Rishabhanatha was unveiled at the Abhay Prabhavana Museum in 2024.[87]

- Idol of Rishabhanatha at Shri Bibrod Adinath Jain Shwetamber Tirth, Bibdod, Ratlam, Madhya Pradesh, India

- Statue of Ahimsa, Maharashtra, 108 feet (33 m)

- 108 feet (33 m) statue at Palitana

- Bawangaja, Madhya Pradesh, 84 feet (26 m)

- The 58.4 feet (17.8 m) colossal at Gopachal Hill

- The 45 feet (14 m) tall rock cut idol at Chanderi

- The 25 feet (7.6 m) idol at Dadabari, Kota

- Idol at Golakot Jain temple

- Idol of Rishabhanatha Decorated with Flowers & Ornaments as per Śvetāmbara Rituals

Temples

Rishabhanatha is one of the five most devotionally revered Tirthankaras, along with Mahavira, Parshvanatha, Neminatha and Shantinatha.[12] Various Jain temple complexes across India feature him, and these are important pilgrimage sites in Jainism. Mount Shatrunjaya, for example, is a hilly part of southern Gujarat, which is believed to have been a place where 23 out of 24 Tirthankaras preached, along with Rishabha.[88] Numerous monks are believed to have attained their liberation from cycles of rebirth there, and a large temple within the complex is dedicated to Rishabha commemorating his enlightenment in Ayodhya. The central Rishabha icon of this complex is called Adinatha or simply Dada (grandfather). This icon is the most revered of all the murtipujaka icons, believed by some in the Jain tradition to have miracle making powers, according to John Cort.[88] In Jain texts, Kunti and the five Pandava brothers of the Hindu Epic Mahabharata came to the hill top to pay respects, and consecrated an icon of Rishabha at Shatrunjaya.[89] Important Rishabha temple complexes include Palitana temples, Dilwara Temples, Kulpakji, Kundalpur, Paporaji, Soniji Ki Nasiyan, Rishabhdeo, Sanghiji, Hanumantal Bada Jain Mandir, Trilok Teerth Dham, Pavagadh and Sarvodaya Jain temple.

See also

Notes

- ^ A non-Jain, Hindu text

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e von Glasenapp 1925, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e Jacobi 1964, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Saraswati 1908, p. 444.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jaini 2000, p. 327.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 64-66.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dalal 2010b, p. 311.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 208-09.

- ^ a b Sangave 2001, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Britannica 2000.

- ^ a b c Umakant 1987, p. 112.

- ^ Varadpande 1983, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Prakash ‘Babloo’, Dr Ravi (11 September 2021). Indian Philosophy and Religion. K.K. Publications.

- ^ Hendricks, Steve (6 September 2022). The Oldest Cure in the World: Adventures in the Art and Science of Fasting. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-64700-002-8.

- ^ a b Yatindrasuri, Acharya. "Rajendrasuri Smarak Granth". jainqq.org. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ Chambers, James (1 July 2015). Holiday Symbols & Customs, 5th Ed. Infobase Holdings, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7808-1365-6.

- ^ Fredricks, Randi (20 December 2012). Fasting: an Exceptional Human Experience. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4817-2379-4.

- ^ a b Upinder Singh 2016, p. 26.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 195.

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dundas 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. xiv.

- ^ Dalal 2010a, p. 27.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. xv.

- ^ Wiley 2004, p. xxix.

- ^ Jestice 2004, p. 419.

- ^ Sangave 2001, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Radhakrishnan 1923, p. 287.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 181.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 83.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 76-79.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 64–66.

- ^ a b Sangave 2001, p. 105.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 9 with footnotes.

- ^ Dalal 2010b, p. 42.

- ^ Wiley 2004, p. 54.

- ^ a b Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 78.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. x.

- ^ Sangave 2001, p. 103.

- ^ a b Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 5.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 89.

- ^ Jaini 2000, pp. 340–341.

- ^ a b c d e f Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b Cort 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 181-182.

- ^ a b Titze 1998, p. 8.

- ^ a b Vijay K. Jain 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (18 April 2014). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-396-7.

- ^ Naik, Prof Katta Narasimha Reddy, Prof E. Siva Nagi Reddy, Prof K. Krishna (31 January 2023). Kalyana Mitra: Volume 6: Architecture. Blue Rose Publishers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ REDDY, Prof Dr PEDARAPU CHENNA (24 February 2022). Nagabharana: Recent Trends in Jainism Studies. Blue Rose Publishers. ISBN 978-93-5611-446-3.

- ^ a b www.wisdomlib.org (20 September 2017). "Part 1: Ṛṣabha's initiation". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ B.K. Jain 2013, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Jestice 2004, p. 738.

- ^ Titze 1998, p. 138.

- ^ JaineLibrary, Anish Visaria. "Search, Seek, and Discover Jain Literature". jainqq.org. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Krishna & Amirthalingam 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 47.

- ^ a b Cort 2010, p. 115.

- ^ Dalal 2010b, pp. 183, 368.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Cort 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Cort 2010, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Popular Prakashan 2000, p. 78.

- ^ "Kamat's Potpourri: History of the Kannada Literature -II". kamat.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ a b Jaini 2000, p. 326.

- ^ Gupta 1999, p. 133.

- ^ "Shri Bhaktamara Mantra (भक्तामर स्त्रोत)", digambarjainonline.com, archived from the original on 15 August 2015, retrieved 15 August 2015

- ^ Rao 1989, p. 13.

- ^ Doniger 1999, p. 549.

- ^ Doniger 1993, p. 243.

- ^ Umakant 1987, p. 113.

- ^ Vyas 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Jain & Fischer 1978, p. 16.

- ^ Tandon 2002, p. 44.

- ^ "Amit Shah felicitated by Jain community", The Statesman, Nashik, PTI, 14 February 2016, archived from the original on 19 March 2016, retrieved 17 December 2016

- ^ "Guinness Book to certify Mangi Tungi idol", The Times of India, 6 March 2016, archived from the original on 31 May 2016, retrieved 17 December 2016

- ^ "108-feet Jain Teerthankar idol enters "Guinness book of records"", The Hindu, 7 March 2016, archived from the original on 13 May 2017, retrieved 17 December 2016

- ^ "Palitana 108 feet high statue of Adinath dada". Dainik Bhaskar. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Bhattacharyya 1977, p. 269.

- ^ Sengupta 1996, pp. 596–600.

- ^ "On a spiritual quest", Deccan Herald, 29 March 2015, archived from the original on 7 November 2016, retrieved 8 March 2017

- ^ Inamdar, Nadeem (6 November 2024). "Country's largest museum dedicated to Jain philosophy inaugurated 50 km from Pune". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ a b Cort 2010, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Cort 2010, pp. 144–145.

Sources

- Ādīśvara-caritra, book 1 of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra, 1931

- Rishabhanatha, in Encyclopaedia Britannica, Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010

- Students' Britannica India, vol. 1–5, Popular Prakashan, 2000, ISBN 0-85229-760-2

- Bhattacharyya, Pranab Kumar (1977), Historical geography of Madhya Pradesh from early records, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 0-8426-9091-3

- Cort, John E. (2001), Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9

- Cort, John E. (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Dalal, Roshen (2010a), Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6

- Dalal, Roshen (2010b), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1381-0

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 0-87779-044-2

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Gupta, Gyan Swarup (1999), India: From Indus Valley Civilisation to Mauryas, Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-7022-763-2

- Jacobi, Hermann (1964), Jaina Sutras, Motilal Banarsidass

- Jain, Babu Kamtaprasad (2013), Digambaratva aur Digambar muni, Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 978-81-263-5122-0

- Jain, Champat Rai (1929), Risabha Deva – The Founder of Jainism, Allahabad: The Indian Press Limited,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Jyotindra; Fischer, Eberhard (1978), Jaina iconography, ISBN 90-04-05260-7

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahavira and his times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-7-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1578-5

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers on Jaina Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1691-9

- Jestice, Phyllis G. (2004), Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-355-1

- Krishna, Nanditha; Amirthalingam, M. (2014) [2013], Sacred Plants of India, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-93-5118-691-5

- Radhakrishnan, S. (1923), Indian Philosophy, The Macmillan Company

- Rao, Raghunadha (1989), Indian Heritage and Culture, Sterling Publishers Pvt., ISBN 978-81-207-0930-0

- Salomon, Richard (1998), Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-839-3

- Saraswati, Dayanand (1908), An English translation of Satyarth Prakash (Reprinted in 1970)

- Sengupta, R (1996), Explorations in Art and Archaeology of South Asia, Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of West Bengal

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1

- Shah, Umakant P. (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-208-X

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 81-230-1013-3

- Titze, Kurt (1998), Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6

- Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1983), Religion and Theatre, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-0-391-02794-7

- Vyas, R. T., ed. (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects, The Director, Oriental Institute, on behalf of the Registrar, M.S. University of Baroda, Vadodara, ISBN 81-7017-316-7

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1999), ISBN 81-208-1376-6

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2004), Historical Dictionary of Jainism, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6558-7

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Joseph Campbell (ed.), Philosophies of India, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.