Loratadine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Claritin, Claratyne, Clarityn, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697038 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Second-generation antihistamine |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | almost 100% |

| Protein binding | 97–99% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6- and 3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 8 hours, active metabolite desloratadine 27 hours |

| Excretion | 40% as conjugated metabolites into urine Similar amount into the feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.120.122 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

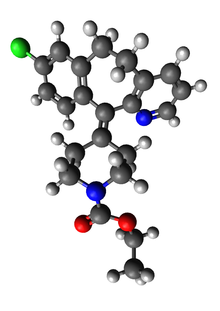

| Formula | C22H23ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 382.89 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Loratadine, sold under the brand name Claritin among others, is a medication used to treat allergies.[5] This includes allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and hives.[5] It is also available in drug combinations such as loratadine/pseudoephedrine, in which it is combined with pseudoephedrine, a nasal decongestant.[5] It is taken orally.[5]

Common side effects include sleepiness, dry mouth, and headache.[5] Serious side effects are rare and include allergic reactions, seizures, and liver problems.[6] Use during pregnancy appears to be safe but has not been well studied.[7] It is not recommended in children less than two years old.[6] It is in the second-generation antihistamine family of medication.[5]

Loratadine was patented in 1980 and came to market in 1988.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] Loratadine is available as a generic medication.[5][10] In the United States, it is available over the counter.[5] In 2022, it was the 72nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 9 million prescriptions.[11][12] In 2022, the combination with pseudoephedrine was the 289th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 500,000 prescriptions.[11][13]

Medical uses

Loratadine is indicated for the symptomatic relief of allergies such as hay fever (allergic rhinitis), urticaria (hives), chronic idiopathic urticaria,[14] and other skin allergies.[15] For allergic rhinitis, loratadine is indicated for both nasal and eye symptoms including sneezing, runny nose, and itchy or burning eyes.[16]

Similarly to cetirizine, loratadine attenuates the itching associated with Kimura's disease.[17]

Combination drugs

Loratadine/pseudoephedrine is a fixed dose combination of the drug with pseudoephedrine, a nasal decongestant.[18]

Dosage forms

The medication is available in many different forms, including tablets, oral suspension, and syrups.[15] Also available are quick-dissolving tablets.[15]

Contraindications

Loratadine is usually compatible with breastfeeding (classified category L-2 - probably compatible, by the American Academy of Pediatrics).[19] In the U.S., it is classified as category B in pregnancy, meaning animal reproduction studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus, but no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women have been conducted.[20]

Adverse effects

As a "non-sedating" antihistamine, loratadine causes less (but still significant, in some cases) sedation and psychomotor retardation than the older antihistamines, because it penetrates the blood/brain barrier less.[21] Headache is also a possible side effect.[15][22]

Unlike earlier-generation antihistamines, loratadine is considered largely free of antimuscarinic effects (urinary retention, dry mouth, blurred vision).[23][24]

Interactions

Substances that act as inhibitors of the CYP3A4 enzyme such as ketoconazole, erythromycin, cimetidine, and furanocoumarin derivatives (found in grapefruit) lead to increased plasma levels of loratadine — that is, more of the drug was present in the bloodstream than typical for a dose. This had clinically significant effects in controlled trials of 10 mg loratadine treatment. [25]

Antihistamines should be discontinued 48 hours before skin allergy tests, since these drugs may prevent or diminish otherwise positive reactions to dermal activity indicators.[15]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Loratadine is a tricyclic antihistamine, which acts as a selective inverse agonist of peripheral histamine H1 receptors.[22][26] The potency of second generation histamine antagonists is (from strongest to weakest) desloratadine (Ki 0.4 nM) > levocetirizine (Ki 3 nM) > cetirizine (Ki 6 nM) > fexofenadine (Ki 10 nM) > terfenadine > loratadine. However, the onset of action varies significantly and clinical efficacy is not always directly related to only the H1 receptor potency, as the concentration of free drug at the receptor must also be considered.[27][26] Loratadine also shows anti-inflammatory properties independent of H1 receptors.[28][29] The effect is exhibited through suppression of the NF-κB pathway, and by regulating the release of cytokines and chemokines, thereby regulating the recruitment of inflammatory cells.[30][31]

Pharmacokinetics

Loratadine is given orally, is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, and has rapid first-pass hepatic metabolism; it is metabolized by isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 system, including CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and, to a lesser extent, several others.[32][33] Loratadine is almost totally (97–99%) bound to plasma proteins. Its metabolite desloratadine, which is largely responsible for the antihistaminergic effects, binds to plasma proteins by 73–76%.[15]

Loratadine's peak effect occurs after 1–2 hours, and its biological half life is on average eight hours (range 3 to 20 hours) with desloratadine's half-life being 27 hours (range 9 to 92 hours), accounting for its long-lasting effect.[34] About 40% is excreted as conjugated metabolites into the urine, and a similar amount is excreted into the feces. Traces of unmetabolised loratadine can be found in the urine.[15]

In structure, it is closely related to tricyclic antidepressants, such as imipramine, and is distantly related to the atypical antipsychotic quetiapine.[35]

History

Schering-Plough developed loratadine as part of a quest for a potential blockbuster drug: a nonsedating antihistamine. By the time Schering submitted the drug to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval, the agency had already approved a competitor's nonsedating antihistamine, terfenadine (trade name Seldane), and, therefore, put loratadine on a lower priority.[36] However, terfenadine had to be removed from the U.S. market by the manufacturer in late 1997 after reports of serious ventricular arrhythmias among those taking the drug.[37][38]

Loratadine was approved by the FDA in 1993.[36] The drug continued to be available only by prescription in the U.S. until it went off patent in 2002.[39] It was then subsequently approved for over-the-counter sales. Once it became an unpatented over-the-counter drug, the price dropped significantly.[citation needed]

Schering also developed desloratadine (Clarinex/Aerius), which is an active metabolite of loratadine.

Society and culture

Over the counter

In 1998, in an unprecedented action in the United States, an American insurance company, Anthem Inc., petitioned the federal Food and Drug Administration to allow loratadine and two other antihistamines to be made available over the counter (OTC) while they were still protected by patents; the administration granted the request, which was not binding on manufacturers.[40] In the United States, Schering-Plough made loratadine available over the counter in 2002.[40] By 2015, loratadine was available over the counter in many countries.[41]

Brands

In 2017, loratadine was available under many brand names and in many forms worldwide, including several combination drug formulations with pseudoephedrine, paracetamol, betamethasone, ambroxol, salbutamol, phenylephrine, and dexamethasone.[42]

Marketing

The marketing of the Claritin brand is important in the history of direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs.[43][44]

The first television commercial for a prescription drug was broadcast in the United States in 1983, by Boots. It caused controversy. The federal Food and Drug Administration responded with strong regulations requiring disclosure of side effects and other information. These rules made pharmaceutical manufacturers balk at spending money on ads that had to highlight negative aspects.[43]

In the mid-1990s, the marketing team for Claritin at Schering-Plough found a way around these rules. They created brand awareness commercials that never actually said what the drug was for, but instead showed sunny images, and the voiceover said such things as "At last, a clear day is here" and "It's time for Claritin" and repeatedly told viewers "Ask your doctor [about Claritin]."[43][44] The first ads made people aware of the brand and increased prescriptions, which led Schering-Plough and others to aggressively pursue the advertising strategy.[44]

In 1998, a 12-page one-shot comic based on the Batman: The Animated Series was given away to advertise Claritin. The book, written by PRIEST, penciled by Joe Staton, and inked by Mike DeCarlo, sees Tim Drake unable to perform his crime-fighting duties because hay fever and antihistamines make him drowsy. After being given a prescription for Claritin, he saved Batman from Poison Ivy.[45]

This trend, along with advice from the Food and Drug Administration's attorneys that it could not win a First Amendment case on the issue, prompted the administration to issue new rules for television commercials in 1997.[43] Instead of including the "brief summary" that took up a full page in magazine ads and would take too long to explain in a short television advertisement, drug makers were allowed to refer viewers to print ads, informative telephone lines, and websites, and to urge people to talk to their doctors if they wanted additional information.[43][46]

Schering-Plough invested US$322 million in Claritin direct-to-consumer advertising in 1998 and 1999, far more than any other brand.[36] Spending on direct-to-consumer advertising by the pharmaceutical industry rose from US$360 million in 1995 to US$1.3 billion in 1998, and by 2006, was US$5 billion.[43]

References

- ^ "Loratadine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Claritin Allergy Product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Clarityn Allergy 10mg Tablets (P & GSL) - Patient Information Leaflet (PIL)". (emc). 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Loratadine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Clarityn Allergy 10mg Tablets (P) - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Loratadine Use During Pregnancy". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 549. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ a b "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Loratadine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Loratadine; Pseudoephedrine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Pons-Guiraud A, Nekam K, Lahovsky J, Costa A, Piacentini A (2006). "Emedastine difumarate versus loratadine in chronic idiopathic urticaria: a randomized, double-blind, controlled European multicentre clinical trial". European Journal of Dermatology. 16 (6): 649–54. PMID 17229605.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jasek W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German). Vol. 1 (2007/2008 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 1768–71. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ "Claritin- loratadine tablet". DailyMed. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Ueda T, Arai S, Amoh Y, Katsuoka K (2011). "Kimura's disease treated with suplatast tosilate and loratadine". European Journal of Dermatology. 21 (6): 1020–1. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1539. PMID 21914581.

- ^ Jasek W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German). Vol. 1 (2007/2008 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 1731–34. ISBN 9783852001814.

- ^ Committee on Drugs (September 2001). "Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk". Pediatrics. 108 (3): 776–89. doi:10.1542/peds.108.3.776. PMID 11533352.

- ^ See S (November 2003). "Desloratadine for allergic rhinitis". American Family Physician. 68 (10): 2015–6. PMID 14655812. Archived from the original on 24 July 2005.

- ^ Monson K. "Claritin and Alcohol". emedtv.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ a b Mutschler E, Geisslinger G, Kroemer HK (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 456–461. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

- ^ AlMasoud N, Bakheit AH, Alshammari MF, Abdel-Aziz HA, AlRabiah H (2022). Loratadine. Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology. Vol. 47. pp. 55–90. doi:10.1016/bs.podrm.2021.10.002. ISBN 978-0-323-85482-5. PMID 35396016.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Antihistamines". Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs. 2016. pp. 606–618. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53717-1.00314-0. ISBN 978-0-444-53716-4.

- ^ Kosoglou T, Salfi M, Lim JM, Batra VK, Cayen MN, Affrime MB (December 2000). "Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic pharmacodynamics of loratadine with concomitant administration of ketoconazole or cimetidine". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 50 (6): 581–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00290.x. PMC 2015013. PMID 11136297.

- ^ a b Devillier P, Roche N, Faisy C (2008). "Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of desloratadine, fexofenadine, and levocetirizine: a comparative review". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 47 (4): 217–30. doi:10.2165/00003088-200847040-00001. PMID 18336052. S2CID 9189476.

- ^ Church MK, Church DS (May 2013). "Pharmacology of antihistamines". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 58 (3): 219–24. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110832. PMC 3667286. PMID 23723474.

- ^ Bielory L, Lien KW, Bigelsen S (2005). "Efficacy and tolerability of newer antihistamines in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis". Drugs. 65 (2): 215–28. doi:10.2165/00003495-200565020-00004. PMID 15631542. S2CID 46791611.

- ^ Canonica GW, Blaiss M (February 2011). "Antihistaminic, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic properties of the nonsedating second-generation antihistamine desloratadine: a review of the evidence". The World Allergy Organization Journal. 4 (2): 47–53. doi:10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182093e19. PMC 3500039. PMID 23268457.

- ^ Hunto ST, Kim HG, Baek KS, Jeong D, Kim E, Kim JH, et al. (July 2020). "Loratadine, an antihistamine drug, exhibits anti-inflammatory activity through suppression of the NF-kB pathway". Biochemical Pharmacology. 177: 113949. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113949. PMID 32251678. S2CID 215408324.

- ^ Fumagalli F, Baiardini I, Pasquali M, Compalati E, Guerra L, Massacane P, et al. (August 2004). "Antihistamines: do they work? Further well-controlled trials involving larger samples are needed". Allergy. 59 (Suppl 78): 74–7. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00573.x. PMID 15245363. S2CID 39936983.

- ^ Nelson WL (2002). "Antihistamines and related antiallergic and antiulcer agents". In Williams DH, Foye WO, Lemke TL (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 805. ISBN 978-0-683-30737-5.

- ^ Ghosal A, Gupta S, Ramanathan R, Yuan Y, Lu X, Su AD, et al. (August 2009). "Metabolism of loratadine and further characterization of its in vitro metabolites". Drug Metabolism Letters. 3 (3): 162–70. doi:10.2174/187231209789352067. PMID 19702548.

- ^ Affrime M, Gupta S, Banfield C, Cohen A (2002). "A pharmacokinetic profile of desloratadine in healthy adults, including elderly". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 41 (Suppl 1): 13–9. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241001-00003. PMID 12169042. S2CID 25555379.

- ^ Kay GG, Harris AG (July 1999). "Loratadine: a non-sedating antihistamine. Review of its effects on cognition, psychomotor performance, mood and sedation". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 29 (Suppl 3): 147–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.0290s3147.x. PMID 10444229. S2CID 26012715.

- ^ a b c Hall SS (11 March 2001). "The Claritin Effect; Prescription for Profit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "FDA Approves Allegra-D, Manufacturer To Withdraw Seldane From Marketplace". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Thompson D, Oster G (May 1996). "Use of terfenadine and contraindicated drugs". JAMA. 275 (17). American Medical Association: 1339–41. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03530410053033. PMID 8614120.

- ^ "Schering-Plough Loses Patent Lawsuit Over Claritin, Opening Door For Cheaper Generic Versions". PRNewswire. Leiner Health Products. 5 August 2003. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ a b Cohen JP, Paquette C, Cairns CP (January 2005). "Switching prescription drugs to over the counter". BMJ. 330 (7481): 39–41. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7481.39. PMC 539854. PMID 15626806.

- ^ Association of the European Self-Medication Industry Database. Loratadine OTC regulation Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed 11 April 2015

- ^ "Loratadine International Brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "The untold story of TV's first prescription drug ad". STAT. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ a b c "DTC: The first 10 years". MM&M. 1 April 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Batman: Claritin Allergy Special, retrieved 6 December 2020

- ^ "Ten Years Later: Direct to Consumer Drug Advertising". Retrieved 26 October 2017.