Eli Lilly and Company

| |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| ISIN | US5324571083 |

| Industry | Pharmaceutical |

| Founded | 1876 |

| Founder | Eli Lilly |

| Headquarters | Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

Key people | |

| Products | Pharmaceutical drugs |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Lilly Endowment (10.8%) |

Number of employees | c. 43,000 (2023) |

| Website | lilly |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3][4][5] | |

Eli Lilly and Company, doing business as Lilly, is an American multinational pharmaceutical company headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, with offices in 18 countries. Its products are sold in approximately 125 countries. The company was founded in 1876 by Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical chemist and Union Army veteran of the American Civil War for whom the company was later named.[6]

As of October 2024, Lilly is the most valuable drug company in the world with a $842 billion market capitalization, the highest valuation ever achieved to date by a drug company.[7] The company is ranked 127th on the Fortune 500 with revenue of $34.12 billion.[8] It is ranked 221st on the Forbes Global 2000 list of the world's largest publicly-traded companies[9] and 252nd on Forbes' list of "America's Best Employers".[10] It is recognized as the top entry-level employer in Indianapolis.[11]

Lilly is known for its clinical depression drugs Prozac (fluoxetine) (1986), Cymbalta (duloxetine) (2004), and its antipsychotic medication Zyprexa (olanzapine) (1996). The company's primary revenue drivers are the diabetes drugs Humalog (insulin lispro) (1996) and Trulicity (dulaglutide) (2014).[12]

Lilly was the first company to mass-produce both the polio vaccine, developed in 1955 by Jonas Salk, and insulin. It was one of the first pharmaceutical companies to produce human insulin using recombinant DNA, including Humulin (insulin medication), Humalog (insulin lispro), and the first approved biosimilar insulin product in the U.S., Basaglar (insulin glargine).[13] Lilly brought exenatide to market—the first of the GLP-1 receptor agonists[14]—followed by blockbuster drugs in the same class such as Mounjaro and Zepbound (tirzepatide).[7]

As of 1997, it was both the largest corporation and the largest charitable benefactor in Indiana.[15] In 2009, Lilly pleaded guilty for illegally marketing Zyprexa and agreed to pay a $1.415 billion penalty that included a criminal fine of $515 million, the largest ever in a healthcare case and the largest criminal fine for an individual corporation ever imposed in a U.S. criminal prosecution of any kind at the time.[16][17]

Lilly is a full member of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America[18] and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA).[19]

History

Founding

The company was founded by Colonel Eli Lilly, a pharmaceutical chemist and Union Army veteran of the American Civil War. Lilly served as the company president until his death in 1898.[20]

In 1869, after working for drugstores in Indiana, Lilly became a partner in a Paris, Illinois-based drugstore with James W. Binford.[21] Four years later, in 1873, Lilly left the partnership with Binford, and returned to Indianapolis. In 1874, Lilly partnered with John F. Johnston, and opened a drug manufacturing operation called Johnston and Lilly.

Two years later, in 1876, Lilly dissolved the partnership, and used his share of the assets to open his own pharmaceutical manufacturing business, Eli Lilly and Company, in Indianapolis.[22][23] The sign outside, above the shop's door, read: "Eli Lilly, Chemist."[20][24][25]

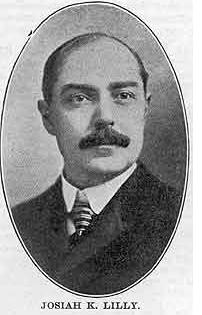

Lilly began his manufacturing venture with three employees, including his son, Josiah (J. K.).[26][23] One of the first medicines that Lilly produced was quinine, a drug used to treat malaria, a mosquito-borne disease.[27] By the end of 1876, sales reached $4,470.[27]

19th century

In 1878, Lilly hired his brother, James, as his first full-time salesman, and the subsequent sales team marketed the company's drugs nationally.[28] By 1879, the company had grown to $48,000 in sales.[27]

The company moved its Indianapolis headquarters from Pearl Street to larger quarters at 36 South Meridian Street. In 1881, the company moved to its current headquarters in Indianapolis's south-side industrial area, and the company later purchased additional facilities for research and production.[29][30] The same year, Lilly incorporated the business as Eli Lilly and Company, elected a board of directors, and issued stock to family members and close associates.[28]

Lilly's first innovative product was gelatin-coating for pills and capsules. The company's other early innovations included fruit flavorings and sugarcoated pills, which made the medicines easier to swallow.[26]

In 1882, Colonel Lilly's only son, Josiah K. Lilly Sr. (J. K.), a pharmaceutical chemist, graduated from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy in Philadelphia, and returned to Indianapolis to join the family business as a superintendent of its laboratory.[31][21][32]

In 1883, the company contracted to mix and sell Succus Alteran, its first widely successful product and one its best sellers. The product was marketed as a "blood purifier" and as a treatment for syphilis, some types of rheumatism, and skin diseases such as eczema and psoriasis.[30][33] Sales from the product provided funds for Lilly to expand its manufacturing and research facilities.[34] By the late 1880s, Colonel Lilly was one of the Indianapolis area's leading businessmen, whose company had over 100 employees and $200,000 ($5,276,296 in 2015 chained dollars) in annual sales.[21]

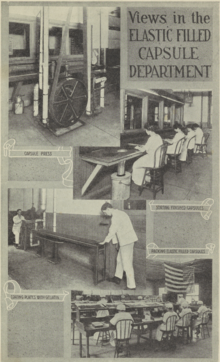

In 1890, Colonel Lilly fully turned over the day-to-day management of the business to J. K., who ran the company for 34 years. The 1890s were a tumultuous decade economically, but the company flourished.[21][35] In 1894, Lilly purchased a manufacturing plant to be used solely for creating capsules. The company also made several technological advances in the manufacturing process, including automating its capsule production. Over the next few years the company annually created tens of millions of capsules and pills.[36]

In 1898, Lilly's son, J. K. Lilly, inherited the company and became its president following Colonel Lilly's death.[37][38] At the time of Colonel Lilly's death, the company had a product line of 2,005 items and annual sales of more than $300,000 ($8,547,600 in 2015 chained dollars).[39] Colonel Lilly was a pioneer in the modern pharmaceutical industry, with many of his early innovations later becoming standard practice. His ethical reforms in a trade that was marked by outlandish claims of miracle medicines began a period of rapid advancement in the development of medicinal drugs.[40] J. K. Lilly continued to advocate for federal regulation on medicines.[41]

As the Lilly company grew, other businesses set up operations near the plant on Indianapolis's near south side. The area developed into one of the city's major business and industrial hubs. Lilly's production, manufacturing, research, and administrative operations in Indianapolis eventually occupied a complex of more than two dozen buildings, which covered 15-block area, in addition to its production plants along Kentucky Avenue.[42]

In addition to Colonel Lilly, his brother, James, and son, Josiah (J. K.), the growing company employed other Lilly family. Colonel Lilly's cousin, Evan Lilly, was hired as a bookkeeper.[35] As young boys, Lilly's grandsons, Eli and Josiah Jr. (Joe), ran errands and performed other odd jobs. Eli and Joe joined the family business after college. Eventually, each grandson served as company president and chairman of the board.[43]

Under J. K.'s leadership, the company introduced scientific management concepts, organized the company's research department, increased its sales force, and began international distribution of its products.[44]

For the rest of the late 19th century, Lilly operated in Indianapolis and the surrounding area as many other pharmaceutical businesses did, manufacturing and selling "sugar-coated pills, fluid extracts, elixirs, and syrups".[33] The company used plants for its raw materials and produced its products by hand. One historian noted, "Although the Indianapolis firm was more careful in making and promoting drugs than the patent medicine men of the era, the company remained ambivalent about scientific research."[33]

20th century

In 1905, J. K. Lilly oversaw a large expansion of the company, and it reached annual sales of $1 million ($26,381,481 in 2015 chained dollars).[38]

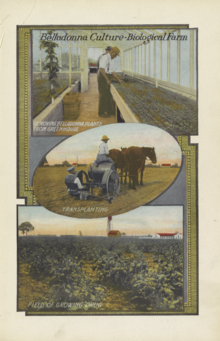

Before and after World War I, the company experienced rapid growth,[33] including expanded manufacturing facilities at its McCarty Street plant, which improved production capacity with a new Science Building (Building 14), opened in 1911, and a new capsule plant (Building 15) in 1913.[45] Om 1913, the company began construction of Lilly Biological Laboratories, a research and manufacturing plant on 150 acres near Greenfield, Indiana.[46][47]

In addition to development of new medicines, the company achieved several technological advances, including automation of its production facilities. Lilly was also an innovator in pill capsule manufacturing. It was among the first manufacturers to insert medications into empty gelatin capsules, which provided a more exact dosage.[20] Lilly manufactured capsules for its own needs and sold its excess capacity to others.[48]

In 1917, Scientific American described Lilly as "the largest capsule factory in the world" and reported that the company was "capable of producing 2.5 million capsules a day".[48] One of Lilly's early innovations was fruit flavoring for medicines and sugar-coated pills to make their medicines easier to swallow.[26] Over the next few years, the company began to create tens of millions of capsules and pills annually.[36]

Other advances improved plant efficiency and eliminated production errors. In 1909, Eli Lilly, grandson of the company's founder, introduced a method for blueprinting manufacturing tickets,[49] which created multiples copies of a drug formula and helped eliminate manufacturing and transcription errors.[48]

In 1919, Josiah hired biochemist George Henry Alexander Clowes as director of biochemical research.

In the 1920s, Eli introduced the new concept of straight-line production to the pharmaceutical industry, where raw materials entered at one end of the facility and the finished product came out the other end, in the company's manufacturing process. Under Eli's supervision, the design for Building 22, a new five-floor plant that opened in Indianapolis in 1926, implemented the straight-line concept to improve production efficiency and lower production costs.[50][51] One historian noted, "It was probably the most sophisticated production system in the American pharmaceutical industry."[51] This more efficient manufacturing process also allowed the company to hire a regular workforce. Instead of recalling workers at peak times and laying them off when production demand fell, Lilly's regular workforce produced less-costly medicines in off-peak times using the same manufacturing facilities.[43]

During the 1920s, the introduction of new products brought the company financial success.[33] In 1921, three University of Toronto scientists, John Macleod, Frederick Banting, and Charles Best, were working on the development of insulin for treatment of diabetes.[52] Clowes proposed a collaboration with the researchers in December 1921, and then again March and May 1922. The researchers were hesitant to work with a commercial drug firm, particularly since they had the Connaught Laboratories' non-commercial facilities at hand. But as limits were reached at the scale to which Connaught could produce insulin, Clowes and Eli Lilly met with the researchers in 1922 to negotiate an agreement with the University of Toronto scientists to mass-produce insulin.[53][54][55] The collaboration greatly accelerated the large-scale production of the extract.[56]

In 1923, the company began selling Iletin, the company's tradename for the first commercially available insulin product in the U.S for the treatment of diabetes.[57] Numerous objections were registered by the Insulin Committee of the University of Toronto in regard to Lilly's use of the term "Iletin", although production continued under this name and the objection was later dropped "as a concession".[58][59]

Also in 1923, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize for their research, which they subsequently shared with co-discoverers Charles Best and James Collip.[60][61] Insulin, "the most important drug" in the company's history, did "more than any other" to make Lilly "one of the major pharmaceutical manufacturers in the world."[52] Eli Lilly and Company enjoyed an effective monopoly on the sale of insulin in the U.S. for almost two years, until the first of the new American licensees, Frederick Stearns & Co., entered the market in June 1924.[62]

The success of insulin enabled the company to attract scientists and, with them, make more medical advances. By the company's 50th anniversary in 1926, its sales had reached $9 million and it was producing over 2,800 products.[43]

In 1928, Lilly introduced Liver Extract 343 for the treatment of pernicious anemia, a blood disorder, in a joint venture with two Harvard University scientists, George Minot and William P. Murphy. In 1930, Lilly introduced Liver Extract No. 55 in collaboration with George Whipple, a University of Rochester scientist.[63] Four years later, in 1934, Minot, Murphy, and Whipple were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their research.[64]

In the 1930s, the company also continued expansion overseas.[65] In 1934, Eli Lilly and Company Limited, the company's first overseas subsidiary was established in London, and a manufacturing plant was opened in Basingstoke.[66][65]

In 1932, despite the economic challenges of the Great Depression, Lilly's sales rose to $13 million.[66] The same year, Eli Lilly, eldest grandson of Col. Lilly who had joined the company in 1909, was named as the company's president, succeeding his father, who remained as chairman of the board until 1948.[38] In his early years at the company, Eli was especially interested in improving production efficiency and introduced a number of labor-saving devices. He also introduced scientific management principles, implemented cost-savings measures that modernized the company,[67] and expanded the company's research efforts and collaborations with university researchers.[68]

In 1934, the firm opened two new facilities on the McCarty Street complex: a replica of Lilly's 1876 laboratory and the new Lilly Research Laboratories, "one of the most fully equipped facilities in the world."[69]

During World War II, the company expanded production to a new high, manufacturing merthiolate, an organomercury compound, and penicillin, a beta-lactam antibiotic. Lilly also cooperated with the American Red Cross to process blood plasma. By the end of World War II, the company had dried over two million pints of blood, "about 20 percent of the United States' total".[70] Merthiolate, first introduced in 1930, was an "antiseptic and germicide" that became a U.S. Army standard issue during World War II.[71][72][73]

International operations expanded even further during World War II.[65] In 1943, Eli Lilly International Corp. was formed as a subsidiary to encourage business trade abroad. By 1948, Lilly employees worked in 35 countries, most of them as sales representatives in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.[65]

In 1945, Lilly began a major expansion effort that included two manufacturing operations in Indianapolis. The company purchased the massive Curtiss-Wright propeller plant on Kentucky Avenue, west of the company's McCarty Street operation. When renovation was completed in mid-1947, the Kentucky Avenue location manufactured antibiotics and capsules and housed the company's shipping department.[74] By 1948, Lilly employed nearly 7,000 people.[24]

In 1948, Eli Lilly, who served as the company's president since 1932, retired from active management, became chairman of the board, and relinquished the presidency to his brother, Josiah K. Lilly Jr. (Joe).[75] During Eli's 16-year presidency, sales rose from $13 million in 1932 to $117 million in 1948. Joe joined the company in 1914 and concentrated on the company's personnel and marketing efforts.[39] He served as company president from 1948 to 1953, then became chairman of the board, and remained in that capacity until his death in 1966.[76]

Throughout the mid-20th century, Lilly continued to expand its production facilities outside of Indianapolis. In 1950, Lilly launched Tippecanoe Laboratories in Lafayette, Indiana,[77] and increased antibiotic production with its patent on erythromycin.

In the 1950s, Lilly introduced two new antibiotics, vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic, and erythromycin.[78] In the 1950s and 1960s, as generic drugs began flooding the marketplace after the expiration of patents, Lilly diversified into other areas, including agricultural chemicals, veterinary medicine products, cosmetics, and medical instruments.

In 1952, the company offered its first public shares of stock, which are traded on the New York Stock Exchange.[79] In 1953, Eugene N. Beesley was named the company's new president, the first non-family member to run the company.[80]

In 1953, following a company reorganization and transition to non-family management, Lilly continued to expand its global presence. In 1954, Lilly formed Elanco Products Company, named after its parent company, for the production of veterinary pharmaceuticals.

Also in 1954, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, now the March of Dimes, contracted with five pharmaceutical companies, Lilly, Cutter Laboratories, Parke, Davis and Company, Pitman-Moore Company, and Wyeth Laboratories to produce Salk's polio vaccine for clinical trials.[81] Lilly's selection to produce the vaccine was, in part, due to its previous experience in collaborations with university researchers.[82] In 1955, Lilly manufactured 60 percent of Salk's polio vaccine.

In the 1960s, Lilly operated 13 affiliate companies outside the United States.[83] In 1962, the company acquired The Distillers Company and established a major factory in Liverpool, England. In 1968, Lilly built its first research facility outside the United States, the Lilly Research Centre, in Surrey, England. In 1969, the company opened a new plant in Clinton, Indiana.[77]

During the 1970s and 1980s, Eli Lilly and Company underwent a flurry of drug production, including Keflex, an antibiotic, in 1971, Dobutrex, a cardiogenic shock heart drug in 1977, Ceclore, which ultimately became the world's top selling oral antibiotic, in 1979, Eldisine, a leukemia drug, Oraflex, an arthritis drug, and Darvon, an opioid drug used in pain management.

In 1971, the company became a component of the S&P 500 Index. To further diversify its product line, Lilly made an uncharacteristic, but ultimately profitable move in 1971, acquiring cosmetic manufacturer Elizabeth Arden, Inc. for $38 million. Although Arden continued to lose money for five years after Lilly acquired it, executive management changes at Arden helped to ultimately turn it into a financial success. By 1982, Arden's "sales were up 90 percent from 1978, with profits doubling to nearly $30 million." In 1987, 16 years after acquiring it, Lilly sold Arden to Fabergé for $657 million.[84]

In 1977, Lilly ventured into medical instruments with the acquisition of IVAC Corporation, which manufactures vital signs and intravenous fluid infusion monitoring systems.[85] The same year, Lilly acquired Cardiac Pacemakers, Inc., a manufacturer of heart pacemakers. In 1980, Lilly acquired Physio-Control, a pioneering company in defibrillation. Other acquisitions included Advance Cardiovascular Systems in 1984, Hybritech in 1986, Devices for Vascular Intervention, in 1989, Pacific Biotech in 1990, and Origin Medsystems and Heart Rhythm Technologies, in 1992. In the early 1990s, Lilly combined its newly acquired medical equipment companies into a Medical Devices and Diagnostics Division that "contributed about 20 percent" of Lilly's annual revenues.[citation needed]

In 1989, a joint agrochemical venture between Elanco and Dow Chemical created DowElanco. In 1997, Lilly sold its 40% share in the company to Dow Chemical for $1.2 billion and the name was changed to Dow AgroSciences.[86]

In 1991, Vaughn Bryson was named CEO of Eli Lilly and Company. During Bryson's 20-month tenure, the company reported its first quarterly loss as a publicly traded company.[87]

In 1993, Randall L. Tobias, vice chairman of AT&T Corporation and a Lilly board member, was named Lilly's chairman, president, and CEO after "product and competitive pressures" had "steadily eroded Lilly's stock price since early 1992."[88] Tobias was the first president and CEO recruited from outside of the company. Under Tobias's leadership, the company "cut costs and narrowed its mission".[89] Lilly sold companies in its Medical Device and Diagnostics Division, expanded international sales, made new acquisitions, and funded additional research and product development.

In 1994, Lilly acquired PCS Systems, the largest drug benefits health maintenance organization at the time, for $4 billion, and later added two similar organizations to its holdings.[90][91]

In 1998, Sidney Taurel, Lilly's former chief operating officer, was named CEO, replacing Tobias. Also in 1998, Lilly formed a joint venture with Icos Corporation (ICOS), a Bothell, Washington-based biotechnology company, to develop and commercialize Cialis, a product for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. In January 1999, Taurel was named chairman. In 2000, Lilly reported $10.86 billion in net sales.

21st century

In September 2002, Lilly agreed to partner with Amylin Pharmaceuticals to develop and commercialize Amylin's exotic new drug based on exendin-4, a novel substance isolated from the venom of the Gila monster.[92] Exenatide, the first of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in April 2005.[14]

In October 2006, Lilly announced its intention to acquire Icos for $2.1 billion, or $32 per share.[93] After its initial attempt to acquire Icos failed under pressure from large institutional shareholders, Lilly increased its offer to $34 per share. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), a proxy advisory firm, advised Icos shareholders to reject the proposal as undervalued.[94][95] But Lilly's offer was approved by Icos' shareholders, and Lilly completed the acquisition of the company in January 2007.[96][97] Lilly subsequently closed Icos' manufacturing operations, terminated nearly 500 Icos employees, leaving 127 employees working at the biologics facility.[98] In December 2007, CMC Biopharmaceuticals A/S (CMC), a Copenhagen-based provider of contract biomanufacturing services, bought the Bothell, Washington-based biologics facility from Lilly and retained the existing 127 employees.[95][98][99]

In January 2009, the largest criminal fine in U.S. history, totaling $1.415 billion, was imposed on Lilly for illegal marketing of its best-selling product, the atypical antipsychotic medication, Zyprexa.[100][16][17]

In January 2011, Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly announced a global agreement to jointly develop and market new APIs for diabetes therapy. Lilly could receive more than $1 billion for their work on the project, while Boehringer Ingelheim could receive more than $800 million from development of the new drugs.[101] Boehringer Ingelheim's oral anti-diabetic Linagliptin, BI 1077, and two of Lilly's insulin analogs, LY2605541 and LY2963016, were in phase II and III of clinical development at that time.

In April 2014, Lilly announced plans to acquire Switzerland-based Novartis AG's animal health business for $5.4 billion in cash to strengthen and diversify its Elanco unit. Lilly said it planned to fund the deal with about $3.4 billion of cash on hand and $2 billion of loans.[102] As a condition of the acquisition, the Sentinel heartworm treatment was divested to Virbac in order to avoid a monopoly in a subsector of the heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) treatment market.[103]

In March 2015, the company announced it would join Hanmi Pharmaceutical in developing and commercializing Hanmi's phase I Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor HM71224 in a deal that could yield $690 million.[104] A day later, however, the company announced another deal with China's Innovent Biologics to co-develop and commercialize at least three of Innovent's treatments over the next decade, in a deal which could generate up to $456 million; the collaboration was subsequently expanded in 2022, according to Innovent. As part of the deal, the company contributed its c-Met monoclonal antibody, and Innovent contributed a monoclonal antibody, which targets CD-20. The second compound from Innovent is a preclinical immunooncology molecule.[105] The following week, the company announced it would restart its collaboration with Pfizer surrounding the Phase III trial of Tanezumab. Pfizer is expected to receive an upfront sum of $200 million from the company.[106]

In April 2015, Lilly engaged CBRE Group to sell its biomanufacturing facility in Vacaville, California,[107] a 52 acres (0.21 km2) campus and facility that is one of the largest biopharmaceutical manufacturing centers in the U.S.[107]

In January 2017, Elanco Animal Health, a subsidiary of the company completed the acquisition of Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc., a subsidiary of Boehringer Ingelheim's U.S. feline, canine, and rabies vaccines portfolio.

In March 2017, Lilly acquired CoLucid Pharmaceuticals for $960 million, obtaining the late clinical-stage migraine therapy candidate, lasmiditan.[108] In August 2017, Lilly and Shionogi jointly licensed their product varespladib to Ophirex for Ophirex's novel snakebite treatment program.[109]

In May 2018, Lilly acquired Armo Biosciences for $1.6 billion.[110] Days later, the company announced it would acquire Aurora kinase A inhibitor developer AurKa Pharma, and control over the lead compound, AK-01, for up to $575 million.[111][112]

In January 2019, Lilly announced it would acquire Loxo Oncology for $235 per share, valuing the business at around $8 billion,which significantly expanded the business's oncology offerings. The deal gave Lilly Loxo's oral TRK inhibitor, Vitrakvi (Larotrectinib), LOXO-292, an oral proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase rearranged during transfection (RET) inhibitor, LOXO-305, an oral Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, and LOXO-195, a follow-on TRK inhibitor.[113][114] In August 2019, Elanco acquired the Bayer animal health business for $7.6 billion.[115][116]

In January 2020, the company announced its acquisition of Dermira for $1.1 billion, gaining control of lebrikizumab,glycopyrronium cloth used in the treatment of hyperhidrosis, and other assets.[117][118][119]

In June 2020, Lilly announced that, in collaboration with Vancouver-based AbCellera, it had begun the world's first study of a potential monoclonal antibody treatment for treatment of COVID-19, with a Phase 1 trial of LY-CoV555.[120][121] By August 2020, the challenging aspects of running a clinical trial in a long-term care facility during a pandemic prompted Lilly to create the first of many customized recreational vehicles into mobile research units (MRU) to meet people where they were and support mobile labs and clinical trial material preparation. A trailer truck could escort the MRU with supplies to create an on-site infusion clinic. Lilly deployed the mobile research unit fleet in response to outbreaks of the virus at long-term care facilities across the U.S. In September 2020, Amgen announced that they had partnered with Lilly to manufacture their COVID-19 antibody therapies.[122]

In October 2020, Lilly announced that its cocktail was effective and that it had filed with the FDA for an emergency use authorization (EUA) for it.[123] The same day, Lilly's corporate rival Regeneron also filed for an EUA for its own monoclonal antibody treatment.[124] The same month, Lilly announced it would acquire Disarm Therapeutics and its experimental treatments for axonal degeneration, via SARM1 inhibitors, for $135 million plus a further $1.225 billion based on regulatory and commercial milestones.[125]

Also in October 2020, Lilly announced that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ACTIV-3 clinical trial evaluating its monoclonal antibody, bamlanivimab (LYCoV555), found that bamlanivimab was not effective in treating people hospitalized with COVID-19,[126] but data showed bamlanivimab might be effective in treating COVID-19 by reducing viral load, symptoms, and the risk of hospitalization in outpatients. Other studies, including the NIH ACTIV-2 trial and its own BLAZE-1 trial, continued to evaluate bamlanivimab.[126] In November 2020, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the investigational monoclonal antibody therapy bamlanivimab for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adult and pediatric patients.[127][128] In December 2020, Lilly announced it would acquire Prevail Therapeutics Inc. for $1 billion, boosting its pipeline in neurodegenerative disease gene therapies.[129]

In April 2021, the FDA revoked the emergency use authorization (EUA) that allowed and signaled FDA agreement for the investigational monoclonal antibody therapy bamlanivimab, when administered alone, to be used for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adults and certain pediatric patients.[130] On 18 May 2021, the FDA accepted Lilly's application for Tyvyt (sintilimab), in combination with Lilly's own Alimta (pemetrexed) and platinum chemotherapy for newly diagnosed nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer.[131] In July 2021, the company announced it would acquire Protomer Technologies for more than $1 billion.[132]

In January 2022, distribution of Lilly's COVID-19 antibody drug was paused due to lack of efficacy against the emerging omicron variant.[133] A second COVID-19 monoclonal antibody therapy, bebtelovimab, developed with AbCellera, was granted Emergency Use Authorization in February 2022, with the U.S. government committing to a $720 million purchase of up to 600,000 doses.[134]

In May 2022, the FDA approved Lilly's type 2 diabetes drug Mounjaro (tirzepatide). In August 2022, following the overturning of Roe v. Wade in the Dobbs decision, the state of Indiana passed a near total ban on abortion, and Lilly said the move would make it difficult to attract talent to the state and that it would be forced to look for "more employment growth" elsewhere.[135]

In October 2022, the business announced it would acquire Akouos Inc. for $487 million in upfront and $123 million deferred payments.[136][137]

As a result of public pressure[138] and increased competition from entities, including Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug, the state of California, and the Inflation Reduction Act capping out-of-pocket insulin costs at $35/month for Medicare patients,[139] Lilly was forced to take measures to make insulin more affordable, capping costs and reducing prices to regain trust and market share.[140][141]

In January 2023, Lilly and TRexBio announced a collaboration and license agreement for three assets to treat immune-mediated diseases.[142] TRexBio received an upfront payment of $55 million as part of this deal.[143] In June the company announced it would acquire startup Emergence Therapeutics[144] for an undisclosed sum and Sigilon Therapeutics for $300 million.[145] The company's 2023 research and development focus has been reported to be on drugs in the obesity, diabetes, Alzheimer's and autoimmune areas.[146]

In July 2023, Lilly announced it would acquire Versanis for $1.93 billion.[147] In October 2023, Eli Lilly acquired Point Biopharma for $1.4 billion.[148]

In November 2023, the FDA approved tirzepatide for the treatment of obesity under the brand name Zepbound.[149]

In March 2024, Lilly announced a deal with Amazon to offer home delivery of certain medications for diabetes, obesity, and migraines, on behalf of LillyDirect.[150]

As of October 2024, tirzepatide's success as a blockbuster weight-loss drug had transformed Eli Lilly into the most valuable drug company in the world with a $842 billion market capitalization, the highest valuation ever achieved by a drug company to date, followed only by Novo Nordisk.[7]

Acquisition history

- Eli Lilly and Company (founded 1876)

- Eli Lilly and Company

- Distillers Company (acq. 1962)

- Elizabeth Arden, Inc. (acq. 1971, sold Fabergé in 1987)

- IVAC Corporation (acq. 1977)

- Cardiac Pacemakers Inc. (acq. 1977)

- Physio-Control Inc (acq. 1980)

- Advance Cardiovasular Systems Inc. (acq. 1984)

- Hybritech (acq. 1986)

- Devices for Vascular Intervention Inc. (acq. 1986)

- Pacific Biotech (acq. 1990)

- Origin Medsystems (acq. 1992)

- Heart Rhythm Technologies, Inc. (acq. 1992)

- PCS System (acq. 1994)

- Icos Corporation (acq. 2007)

- Hypnion, Inc

- ImClone Systems

- SGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc (acq. 2008)

- Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (acq. 2010)

- Alnara Pharmaceuticals(acq. 2010)

- CoLucid Pharmaceuticals (acq. 2017)

- Armo Biosciences (acq. 2018)

- AurKa Pharma (acq. 2018)

- Loxo Oncology (acq. 2019)

- Disarm Therapeutics (acq. 2020)

- Prevail Therapeutics Inc (acq. 2020)

- Elanco Products Company (established 1954 as a division of Eli Lilly and Company)

- DowElanco (established 1989 as joint venture with Dow Chemical, sold stake 1999 to Dow)

- Ivy Animal Health (acq. 2007)

- Pfizer Animal Health (acq. 2010)

- Janssen Pharmaceutica Animal Health (acq. 2011)

- ChemGen Corp(acq. 2012)

- Lohmann SE(acq. 2014)

- Novartis Animal Health (acq. 2014)

- Bayer Animal Health (acq. 2019)

- Protomer Technologies (acq. 2021)

- Akouos Inc (acq. 2022)

- Dice Therapeutics[151] (acq. 2023)

- Emergence Therapeutics (acq. 2023)

- Sigilon Therapeutics (acq. 2023)

- Versanis Bio (acq. 2023)[152]

- Mablink Bioscience (acq. 2023)

- Point Biopharma (acq. 2023)

- Eli Lilly and Company

Collaborative research

Eli Lilly and Company has a long history of collaboration with research scientists. In 1886, Ernest G. Eberhardt, a chemist, joined the company as its first full-time research scientist.[153] Lilly also hired two botanists, Walter H. Evans and John S. Wright, to join its early research efforts.[34][154]

After World War I, the company's expanded production facilities and introduction of new management methods set the stage for Lilly's next crucial phase—its "aggressive entry into scientific research and development."[24] The first big step came in 1919 when Josiah Lilly hired biochemist George Henry Alexander Clowes as director of biochemical research.[155] Clowes had extensive medical research expertise and links to the scientific research community, which led to the company's collaborations with researchers in the U.S. and elsewhere.[156] Clowes's first major collaboration with researchers who developed insulin at the University of Toronto significantly impacted the company's future.[156] Lilly's success with insulin production secured the company's position as a leading research-based pharmaceutical manufacturer, allowing it to attract and hire more research scientists and to collaborate with other universities in additional medical research.[157]

In 1934, the company built a new research laboratory in Indianapolis.[52] As part of its research and product development process Lilly also conducted clinical studies at Indianapolis City Hospital. Lilly continues to conduct clinical studies to test medications before their introduction to the market.

In 1949, Eli Lilly went into partnership with the United States Army Reserve, setting up a local Strategic Intelligence Research and Analysis (SIRA) Unit to allow employees to research company data for the scientific logistics and Eurasian fields of study.

In 1998, the company dedicated new laboratories for clinical research at the Indiana University Medical Center in Indianapolis.

Publicly funded research

Lilly is involved in publicly funded research projects with other industrial and academic partners. One example is non-clinical safety assessment is the InnoMed PredTox, a collaboration with pharmaceutical companies, research organizations, and the European Commission to improve the safety of drugs.[158][159]

In 2008, this consortium, which included Lilly S.A. in Switzerland, secured an €8 million budget for a 40-month project that was coordinated by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), an organization who represents the research-based pharmaceutical industry and biotech companies operating in Europe.[159][160][161]

In 2008, Lilly's activities included research projects within the framework of the Innovative Medicines Initiative, a public-private research initiative in Europe that is a joint effort of the EFPIA and the European Commission.[162][163][164]

Public-private engagement

Academia

- Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM), donor[165]

- Population Health Research Institute (PHRI) at McMaster University, partner[166]

- University of Toronto, donor to the Boundless Campaign[167] and member of the President's Circle[168]

- University of Washington, member of the Honor Roll of Donors, having contributed between $10 million and $50 million to funding the school as of 2020[169]

Conferences and summits

- World Neuroscience Innovation Forum, stakeholder sponsor[170]

Media

Medical societies

- American Society of Hematology, sponsor[172]

- Arthritis Society, national partner[173]

- Endocrine Society, corporate Liaison Board member[174]

- European Society of Cardiology, sponsor of the EURObservational Research Programme[175]

Non-governmental organizations

- HOPE Worldwide, partner[176]

Political lobbying

- Alliance for Competitive Taxation, member[177]

- BIOTECanada, member company.[178] BIOTECanada lobbies the Canadian government for policies favorable to the pharmaceutical industry.[179]

- Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH), donor, given between $5,000,000 and $9,999,999 between 1997 and 2020, contributing to funding the activities of the National Institutes of Health[180]

- Innovative Medicines Canada, member[181] The group lobbies the Government of Ontario and House of Commons of Canada through Rubicon Strategy, a firm owned by Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario campaign manager Kory Teneycke.[182][183][184]

- International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, member[185]

- National Health Council (NHC), member organization. NHC is a non-profit organization that lobbies the U.S. federal government on issues related to healthcare reform.[186]

- National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC), member company. NPC is a non-profit that advocates for expanded research funding and innovation.[187]

- Personalized Medicine Coalition (PMC), member. PMC is a lobbying group with ties to members of the United States Congress.[188][189]

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), member company. PhRMA is a trade association that lobbies the U.S. federal government on behalf of the pharmaceutical industry.[190][191]

- Research!America, member organization. Research!America is a medical research advocacy group.[192]

Professional associations

- AdvaMed, member[193]

- Canadian Rheumatology Association, sponsor[194]

- Canadian Urological Association, sponsor[195]

- Mood Disorders Association of Ontario (MDAO), donor[196]

Public health

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), donor[197]

- Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), donor to the SickKids Foundation[198]

- Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PMCC), conference sponsor[199] and donor to the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation[200]

- Scarborough Health Network (SHN), donor to the SHN Foundation[201]

- Sinai Health Foundation, donor. The foundation funds Mount Sinai Hospital, Bridgepoint Active Healthcare, and the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, Ontario.[202]

- Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, donor[203]

Research and development

- Arthritis Australia, sponsor[204]

- BioFIT, sponsor[205] BioFIT holds events to connect academia, pharmaceutical companies, and investors in the field of life sciences and biotechnology.

- Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration and Aging, partner organization[206]

- Colorectal Cancer Canada, sponsor[207]

- COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator, collaborator[208]

- Diabetes Canada, corporate partner[209]

- GIANT Health, event sponsor[210]

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), corporate partner[211]

- New Brunswick Health Research Foundation (NBHRF), sponsor[212]

- Pinnacle Research Group, sponsor[213]

- Radcliffe Cardiology, industry partner[214]

Pharmaceutical brands

The company's most important products introduced prior to World War II included insulin, which Lilly marketed as Iletin (Insulin, Lilly), Amytal, Merthiolate, ephedrine, and liver extracts.[72]

During World War II, Lilly produced penicillin and other antibiotics. In addition to penicillin, other wartime production included "antimalarials," blood plasma, encephalitis vaccine, typhus and influenza vaccine, gas gangrene antitoxin, Merthiolate, and Iletin (Insulin, Lilly).[215]

Among the company's other pharmaceutical developments are cephalosporin, erythromycin, and Prozac (fluoxetine), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for the treatment of clinical depression. Ceclor, introduced in the 1970s, was an oral cephalosporin antibiotic. Prozac, introduced in the 1980s, quickly became the company's best-selling product for treatment of depression, but Lilly lost its U.S. patent protection for the product in 2001. Among other distinctions, Lilly is the world's largest manufacturer and distributor of medications used in a broad range of psychiatric and mental health-related conditions, including clinical depression, generalized anxiety disorder, narcotic addiction, insomnia, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and others.[citation needed]

In March 2023, Eli Lilly announced a $35 cap on the price of monthly insulin to be put in place immediately in order to be in line with the Inflation Reduction Act.[216]

Medications that provide significant revenue for Lilly include Trulicity, Mounjaro, Verzenio, Taltz, Jardiance, Humalog, Cyramza, Olumiant, Emgality, Tyvyt, Retevmo, Alimta, and Zepbound.[2]

Cialis

In 2003, Eli Lilly and Company introduced Cialis (tadalafil), a competitor to Pfizer's blockbuster Viagra for erectile dysfunction. Cialis maintains an active period of 36 hours, causing it sometimes to be dubbed the "weekend pill". Cialis was developed in a partnership with biotechnology company Icos Corporation. In December 2006, Lilly bought Icos in order to gain full control of the product.[217]

Cymbalta

Another Lilly manufactured anti-depressant, Cymbalta, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor used predominantly in the treatment of major depressive disorders and generalized anxiety disorder, ranks with Prozac as one of the most financially successful pharmaceuticals in industry history. It is also used in the treatment of fibromyalgia, neuropathy, chronic pain and osteoarthritis.[218][219]

Kisunla

Donanemab, sold under the brand name Kisunla, is a monoclonal antibody used for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Kisunla was approved by the US FDA in 2024.[220][221]

Gemzar

In 1996, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved gemcitabine (Gemzar) for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Gemzar is commonly used in the treatment of pancreatic cancer, usually in coordination with 5-FU chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Gemzar also is routinely used in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer.[citation needed][222]

Methadone

Lilly was the first distributor of methadone in the United States, an analgesic used frequently in the treatment of heroin, opium and other opioid and narcotic drug addictions.[223][224] Eli Lilly was able to acquire the right to produce the drug commercially for just $1 because the patent rights of the original patent holders, IG Farben and Farbwerke Hoechst, were not protected after the Allies of World War II seized all German patents, research records and trade names. Eli Lilly introduced the drug to the United States in 1947, marketed under the trade name "Dolophine".[225]

Prozac

Prozac was one of the first therapies in its class to treat clinical depression by blocking the uptake of serotonin within the human brain. Prozac was approved by the US FDA in 1987 for use in treating depression, with generic versions appearing after 2002.

Secobarbital

Lilly has manufactured Secobarbital, a barbiturate derivative with anesthetic, anticonvulsant, sedative and hypnotic properties. Lilly marketed Secobarbital under the brand name Seconal. Secobarbital is indicated for the treatment of epilepsy, temporary insomnia and as a pre-operative medication to produce anesthesia and anxiolysis in short surgical, diagnostic, or therapeutic procedures which are minimally painful. With the onset of new therapies for the treatment of these conditions, Secobarbital has been less utilized, and Lilly ceased manufacturing it in 1999.[citation needed]

Secobarbital gained considerable attention during the 1970s, when it gained wide popularity as a recreational drug. In September 1970, rock guitarist legend Jimi Hendrix died from a secobarbital overdose. In June 1969, secobarbital overdose was the cause of death of actress Judy Garland. The drug was a central part of the plot of the hugely popular novel Valley of the Dolls (1966) by Jacqueline Susann in which three highly successful Hollywood women each fall victim, in various ways, to the drug. The novel was later released as a film by the same name.[citation needed]

Thiomersal

Lilly has developed the vaccine preservative thiomersal (also called merthiolate and thimerosal). Thiomersal is effective by causing susceptible bacteria to autolyze. Launched in 1930, merthiolate was a mercury-based antiseptic and germicide that "had been formulated at the University of Maryland with support of a Lilly research fellowship."[72] In November 2002,[226] congressional Republicans inserted a provision into a domestic security bill that President George W. Bush signed into a law, protecting Eli Lilly from all suits in the federal courts, alleging that the drug, Thiomersal caused autism and other neurological disorders in children, such that all such matters be heard by a special master appointed for the purpose, rather than regular federal courts. Its toxicology was that it metabolized into ethylmercury (C2H5Hg+) and thiosalicylate, in the body. However, since the mid 2000’s it has mostly fallen out of use.

Zyprexa

Zyprexa (Olanzapine) (for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as well as off-label uses) Released in 1996, (see Illegal marketing of Zyprexa) it was the company's best selling drug through 2010, when the patent expired.[227]

Leadership

After three generations of Lilly family leadership under company founder, Col. Eli Lilly, his son, Josiah K. Lilly Sr., and two grandsons, Eli Lilly Jr. and Josiah K. Lilly Jr., the company announced a reorganization in 1944 that prepared the way for future expansion and the eventual separation of company management from its ownership.[228] The large, complex corporation was divided into smaller groups headed by vice presidents and in 1953 Eugene N. Beesley was named the first non-family member to become the company's president.[83]

Although Lilly family members continued to serve as chairman of the board until 1969, Beesley's appointment began the transition to non-family management.[83] In 1972 Richard Donald Wood[229] became Lilly's president and CEO after the retirement of Burton E. Beck.[230] In 1991 Vaughn Bryson became president and CEO[229] and Wood became board chairman.[231] During Bryson's 20-month tenure as Lilly's president and CEO, the company reported its first quarterly loss as a publicly traded company.[87]

Randall L. Tobias, a vice chairman of AT&T Corporation, was named chairman, president, and CEO in June 1993. Tobias, a Lilly board member since 1986, was recruited from outside the company's executive ranks[87] first to replace Lilly's president and CEO, Vaughn Bryson, at Bryson's predecessor and then board chairman Richard Wood's urging and then, in short order, also Wood.[229] Tobias later became the US director of Foreign Assistance and administrator of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), with the rank of ambassador.[232]

Sidney Taurel, former chief operating officer of Lilly, was named CEO in July 1998 to replace Tobias, who retired. Taurel became chairman of the board in January 1999.[233] Taurel retired as CEO in March 2008, but remained as chairman of the board until 31 December 2008. John C. Lechleiter was elected as Lilly's CEO and president, effective 1 April 2008. Lechleiter had served as Lilly's president and chief operating officer since October 2005.[234]

In July 2016 it was announced that Lechleiter would be retiring. David Ricks was voted to succeed his position.[235]

Community service

The Lilly family as well as Eli Lilly and Company has a long history of community service. Around 1890 Col. Lilly turned over operation of the family business to his son, Josiah, who ran the company for the next several decades.[34] Col. Lilly remained active in civic affairs and assisted a number of local organizations, including the Commercial Club of Indianapolis, which later became the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce,[236] and the Charity Organization Society, a forerunner to the Family Services Association of Central Indiana, an organization supported by United Way.[34][237] Josiah's sons, Eli and Joe, were also philanthropists who supported numerous cultural and educational organizations.[238]

Josiah Sr. continued his father's civic mindedness and began the company tradition of sending aid to disaster victims.[38] Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the company sent much needed medicine to support recovery efforts and provided relief after the 1936 Johnstown Flood.[38]

In 1917, Lilly Field Hospital 32, named in Josiah's honor, was equipped in Indianapolis and moved overseas to Contrexville, France, during World War I, where it remained in operation until 1919.[38] Throughout World War II, Lilly manufactured more than two hundred products for military use, including aviator survival kits and seasickness medications for the D-Day invasion.[66] In addition Lilly dried more than two million pints of blood plasma by the war's end.[70]

Lilly Endowment

In 1937, Josiah K. Lilly Sr. and his two sons, Eli and Joe, founded the Lilly Endowment, a private charitable foundation, with gifts of Lilly stock.[239] The endowment still owns 11.3% of the company.[5]

Eli Lilly and Company Foundation

The Eli Lilly and Company Foundation, which is separate from the Lilly Endowment, operates as a tax-exempt private charitable foundation that the company established in 1968. The Foundation is funded through Lilly's corporate profits.[240]

Controversies

BGH

In August 2008, Eli Lilly purchased the right to manufacture bovine growth hormone, used to increase milk production in dairy cattle, from Monsanto.[241] Use of the supplement has become controversial due to the animal ethics and human health concerns.[242]

340B

In 2021, Eli Lilly filed a court motion against in response to an advisory opinion of the Department of Health and Human Services indicating that Eli Lilly and other drug manufacturers must continue to offer reduced pricing to covered outpatient drugs through pharmacies contracted to hospitals rather than only to the hospitals themselves.[243][244][245]

Prozac

In September 1989, Joseph T. Wesbecker killed eight people and injured twelve before committing suicide.[246] His relatives and victims blamed his actions on the Prozac medication he had begun taking a month prior. The incident set off a chain of lawsuits and public outcries.[247] Lawyers began using Prozac to justify the abnormal behaviors of their clients.[248] Eli Lilly was accused of not doing enough to warn patients and doctors about the adverse effects, which it had described as "activation", years prior to the incident.[249] The link between suicide and antidepressants remains a subject of public and academic dispute.

In October 2004, the FDA added a boxed warning to all antidepressant drugs regarding use in children.[250] In 2006, the FDA included adults aged 25 or younger.[251] In February 2018, the FDA ordered an update to the warnings based on statistical evidence from twenty-four trials in which the risk of such events increased from two percent to four percent relative to the placebo trials.[252]

Illegal marketing of Zyprexa

Eli Lilly has faced many lawsuits from people who claimed they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking olanzapine (branded Zyprexa), an antipsychotic medication, as well as by various governmental entities, insurance companies, and others. Internal documents provided to The New York Times revealed that Lilly had downplayed the risks of Zyprexa. According to the documents, 16 percent of people taking Zyprexa gained more than 66 pounds in their first year, a much larger figure than Eli Lilly had shared with doctors.[253]

In 2006, Lilly paid $700 million to settle around 8,000 of these lawsuits,[254] and in early 2007, Lilly settled around 18,000 suits for $500 million, which brought the total Lilly had paid to settle suits related to the drug to $1.2 billion.[253][255]

In March 2008, Lilly settled a suit with the state of Alaska,[256] and in October 2008, Lilly agreed to pay $62 million to 32 states and the District of Columbia to settle suits brought under state consumer protection laws.[257] In 2009, four sales representatives for Eli Lilly filed separate qui tam lawsuits against the company for illegally marketing Zyprexa for uses not approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Eli Lilly pleaded guilty to a US federal criminal misdemeanor charge of illegally marketing Zyprexa, actively promoting the drug for off-label uses, particularly for the treatment of dementia in the elderly.[258] The $1.415 billion penalty included an $800 million civil settlement, a $515 million criminal fine, and forfeit assets of $100 million.[16] The US Justice Department said the criminal fine of $515 million was the largest ever in a healthcare case and the largest criminal fine for an individual corporation ever imposed in a US criminal prosecution of any kind.[16][17] "That was a blemish for us," John C. Lechleiter, CEO of Lilly, said. "We don't ever want that to happen again. We put measures in place to assure that not only do we have the right intentions in integrity and compliance, but we have systems in place to support that."[259] In an internal email, Lechleiter had stated "we must seize the opportunity to expand our work with Zyprexa in this same child-adolescent population" for off-label use.[260]

In January 2020, lawyer James Gottstein published a book titled The Zyprexa Papers summarizing the legal activities surrounding Zyprexa, and their impact on the political landscape of psychiatry and antipsychiatry in the US.[261] The book details of how he obtained the Zyprexa papers, including how Will Hall and a small group of "psychiatric survivors" untraceably spread the Zyprexa Papers on the Internet and his battles on behalf of Bill Bigley, the psychiatric patient whose ordeal made possible the exposure of the Zyprexa Papers.[262]

Discrimination

In March 2021, Eli Lilly and Company was accused of sex discrimination by a former lobbyist who claimed she was forced to work in a sexually hostile work environment.[263] The parties involved settled for an undisclosed amount in June 2021.[264]

In September 2021, Eli Lilly and Company was accused in a federal court lawsuit of discriminating against older applicants for sales positions based on their implementation of hiring quotas for millennials.[265]

Canada patent lawsuit

In September 2013, Eli Lilly sued Canada for violating its obligations to foreign investors under the North American Free Trade Agreement by allowing its courts to invalidate patents for Strattera and Zyprexa.[266] Canadian courts found Strattera's seven-week long study of twenty-two patients, too short and too narrow in scope to qualify for the patent. The Zyprexa patent was invalidated because it had not achieved its promised utility. The company sought damages in the amount of $500 million for lost profits. They ultimately lost the case in 2017.[267]

Illegal marketing of Evista

Evista is a medication typically used to prevent and treat osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

In December 2005, Eli Lilly and Company agreed to plead guilty and pay $36 million in connection with the illegal promotion of the drug.[268] Sales representatives were trained to promote Evista for breast cancer and cardiovascular disease, to prompt or bait questions by doctors, and to send them unsolicited letters promoting Evista for unapproved use. The company distributed a videotape in which a sales representative declared that "Evista truly is the best drug for the prevention of all these diseases." Some sales representatives had also been instructed to conceal the disclosure page which stated that the effectiveness of the drug in reducing breast cancer risks had not yet been established.[citation needed]

Insulin pricing

In January 2019, lawmakers from the United States House of Representatives sent letters to Eli Lilly and other insulin manufacturers asking for explanations for their rapidly raising insulin prices. The annual cost of insulin for people with type 1 diabetes in the US almost doubled from $2,900 to $5,700 over the period from 2012 to 2016.[269]

Renewed attention was brought to Eli Lilly's pricing of insulin in November 2022, after a verified Twitter account impersonating Eli Lilly posted on Twitter that insulin would now be free.[270][271][272] The following year, the company announced that it would be reducing the out-of-pocket price of insulin to $35 a month. The company also stated that it would lower the price of Humalog from $275 a month to $66 and that it would offer insulin glargine at a 78% discount compared to rival company Sanofi. Despite this, the reduced costs will not apply to Eli Lilly's newer brands of insulin, and the company's pricing is still significantly higher than it was several decades prior.[273]

References

- ^ "Google Parent Alphabet Poaches Eli Lilly Finance Chief Ashkenazi". MSN. 5 June 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Eli Lilly and Company 2023 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Eli Lilly and Company 2023 Annual Report on Form 10-K" (PDF). Eli Lilly. 21 February 2024.

- ^ "Eli Lilly and Company 2023 Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 17 March 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b Lee, Jaimy (9 February 2021). "Lilly promotes Anat Ashkenazi to CFO, says previous CFO had 'inappropriate' communication with employees". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ HannahBlake (29 July 2013). "A history of... Eli Lilly & Co -". pharmaphorum.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Barnes, Oliver (2 October 2024). "Can Eli Lilly become the first $1tn drugmaker?". Financial Times.

- ^ "Eli Lilly". Fortune. 17 December 2023. Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "Forbes: The World's Biggest Public Companies". Forbes. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Forbes: America's Best Employers". Forbes. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ "Top 100 Entry-Level Employers in Indianapolis for 2024". www.choicequad.com. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Eli Lilly Company Profile". Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Swiatek, Jeff (28 December 2015). "10 all-time greatest Eli Lilly drugs". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b Pollack, Andrew (30 April 2005). "Lizard-Derived Diabetes Drug Is Approved by the F.D.A.". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ Price, Nelson (1997). Indiana Legends: Famous Hoosiers from Johnny Appleseed to David Letterman. Carmel, Indiana: Guild Press of Indiana. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-57860-006-9.

- ^ a b c d "Eli Lilly and Company Agrees to Pay $1.415 Billion to Resolve Allegations of Off-label Promotion of Zyprexa". 09-civ-038. United States Department of Justice. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ a b c "Pharmaceutical Company Eli Lilly to Pay Record $1.415 Billion for Off-Label Drug Marketing" (PDF). United States Attorney, Eastern District of Pennsylvania. United States Department of Justice. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Members". Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "SDG Group Customers: Eli Lilly". SDG Group. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b c "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bodenhamer, David J.; Barrows, Robert G., eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 911. ISBN 978-0-253-31222-8.

- ^ "Colonel Eli Lilly (1838–1898)" (PDF). Lilly Archives. January 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b Madison, James H. (1989). Eli Lilly: A Life, 1885–1977. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-87195-047-5.

- ^ a b c Bodenhamer and Barrows, p. 540.

- ^ The Indiana Historical Society recreated a replica of the first Lilly laboratory on Pearl Street for its exhibition, "You Are There: Eli Lilly at the Beginning," at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center in Indianapolis. The temporary exhibition (1 October 2016, to 20 January 2018) also included costumed interpreters portraying Colonel Lilly and others. See "The Man Behind State's Most Successful Startup". Kendallville New Sun. Kendallville, Indiana: KPC News. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2016. See also Alvarez, Tom, ed. (Fall 2016). "Fall Arts Guide". UNITE Indianapolis. Indianapolis: Joey Amato: 32. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b c Price, Indiana Legends, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Price, Indiana Legends, p. 57.

- ^ a b Kahn, E. J. (1975). All In A Century: The First 100 Years of Eli Lilly and Company. West Cornwall, CT. p. 23. OCLC 5288809.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). p. 1 and 4. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 27.

- ^ Albert Nelson Marquis, ed. (1916). "Lilly, Josiah Kirby". Who's Who in America: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living Men and Women of the United States. A. N. Marquis & Company. p. 1482.

- ^ Nelson Price (1997). Indiana Legends: Famous Hoosiers From Johnny Appleseed to David Letterman. Carmel, IN: Guild Press of Indiana. p. 59. ISBN 1-57860-006-5.

- ^ a b c d e James H. Madison (1989). "Manufacturing Pharmaceuticals: Eli Lilly and Company, 1876–1948" (PDF). Business and Economic History. 18. Business History Conference: 72. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b Price, Indiana Legends, p. 60.

- ^ a b Podczeck, Fridrun; Jones, Brian E. (2004). Pharmaceutical Capsules. Chicago: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-85369-568-4.

- ^ Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 913.

- ^ a b c d e f "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 912.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, pp. 17–18, 21.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, pp. 51, 112–15.

- ^ Taylor Jr., Robert M.; Stevens, Errol Wayne; Ponder, Mary Ann; Brockman, Paul (1989). Indiana: A New Historical Guide. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-87195-048-2.

- ^ a b c "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). pp. 2, 5 and 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "The Pharmaceutical Industry in Indiana" (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 30.

- ^ Taylor; et al. Indiana: A New Historical Guide. p. 481.

- ^ "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2016. Note: This includes Eugene F. Rodman (April 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Lilly Biological Laboratories" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2016. and Accompanying photographs.

- ^ a b c Madison, "Manufacturing Pharmaceuticals," Business and Economic History, p. 73.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 29.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 46.

- ^ a b Madison, "Manufacturing Pharmaceuticals," Business and Economic History, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 76.

- ^ Bliss, Michael (1984). The Discovery of Insulin. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226058986. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Rutty, Christopher J. "Connaught Laboratories & The Making of Insulin". Connaught Fund. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 55–57.

- ^ Roberts, Jacob (2015). "Sickening sweet". Distillations. 1 (4): 12–15. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 61.

- ^ Bliss, Michael (1984). The Discovery of Insulin. University of Chicago Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 9780226058986. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Hutchison, F. Lorne (18 October 1924). "Notes on the history of the Insulin Committee's objection to Lilly's use of the term Iletin". University of Toronto Libraries. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Insulin wins a great prize". University of Toronto Libraries. New York, NY: Literary Digest. 8 December 1923. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Citation to F. G. Banting and J. J. R. Macleod accompanying the Nobel Prize". University of Toronto Libraries. Stockholm, Sweden: Royal Karolinska Institute. 1923. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Bliss, Michael (1984). The Discovery of Insulin. University of Chicago Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780226058986. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 66–67.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 111.

- ^ a b c "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 28–34.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 62–65.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 91.

- ^ a b Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 105.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 65 and 106.

- ^ a b c Madison, James H. (1989). Eli Lilly: A Life, 1885–1977. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-87195-047-5.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 107–8.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 110.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 91, 119–20.

- ^ Madison, Eli Lilly, p. 120 and 249.

- ^ a b Bodenhamer and Barrows, p. 541.

- ^ Nicolaou, Kyriacos C.; Rigol, Stephan (1 February 2018). "A brief history of antibiotics and select advances in their synthesis". The Journal of Antibiotics. 71 (2): 153–184. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.62. ISSN 1881-1469. PMID 28676714.

- ^ Price, Indiana Legends, p. 61.

- ^ "Eugene N. Beesley Dead at 67;Ex-Chairman of Eli Lilly &Co". The New York Times. 9 February 1976. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Polio and Eli Lilly and Company" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Polio and Eli Lilly and Company" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ a b c "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Eli Lilly Signs Agreement To Acquire Ivac Corp". The New York Times. 14 October 1977. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Dow to Buy Lilly's 40% Stake in Dow Elanco". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. 16 May 1997. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Associated Press (26 June 1993). "New Lilly Chief Doesn't Have Own 'Agenda'". Kokomo Tribune. Kokomi, IN. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Associated Press (26 June 1993). "Eli Lilly CEO Resigns in Dispute". Kokomo Tribune. Kokomi, IN.

- ^ "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). p. 8 and 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Eli Lilly & Company" (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Armor, Nancy (31 July 1994). "New Lilly Chief Nurtures Change". Kokomo Tribune.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (21 September 2002). "Eli Lilly in Deal For the Rights To a New Drug For Diabetes". The New York Times. p. C1.

- ^ "Lilly Increases Offer for Icos; Shareholders' Vote Is Put Off". The New York Times. Associated Press. 19 December 2006. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (13 January 2007). "Reject Icos Offer, Holders of Shares Advised". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ a b Timmerman, Luke (7 November 2006). "Proposed Icos Sale Gets More Criticism: Payouts for Execs Called 'Overkill'". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ James, Andrea (26 January 2007). "Icos Voters Approve Buyout by Eli Lilly". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Eli Lilly Completes Icos Takeover". The Seattle Times. 30 January 2007. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ a b Tartakoff, Joseph (5 December 2007). "New Owner Will Invest $50 Million in Icos Facility". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (12 December 2006). "All Icos Workers Losing Their Jobs". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Eli Lilly Gets $1.4B Fine for Zyprexa Off-Label Marketing". medheadlines.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Murphy, Tom (12 January 2011). "Lilly, Boehringer Collaborate on Diabetes Drugs". Anderson Herald Bulletin. Anderson, IN. p. A7.

- ^ Sen, Arnab (22 April 2014). Warrier, Gopakumar (ed.). "Eli Lilly to buy Novartis' animal health unit for $5.4 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Bartz, Diane (22 December 2014). Benkoe, Jeffrey; Baum, Bernadette (eds.). "Lilly must divest Sentinel products after FTC nod on Novartis deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Eli Lilly to Co-Develop Hanmi BTK Inhibitor for Up-to-$690M". GEN News Highlights. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Lilly Joins Innovent in Up-to-$456M+ Cancer Collaboration". GEN News Highlights. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Philippidis, Alex (23 March 2015). "Pfizer, Lilly to Resume Phase III Tanezumab Clinical Program". GEN News Highlights. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Eli Lilly Biomanufacturing Plant For Sale". Advantage Business Media. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2015.

- ^ "Lilly to Buy CoLucid for $960M to Acquire Late-Stage Migraine Drug - GEN Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News - Biotech from Bench to Business - GEN". 18 January 2017. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Lewin, Matthew (28 August 2017). "Ophirex Licenses Lilly - Shionogi Data for Novel Snakebite Treatment Development Program". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Mishra, Manas (10 May 2018). "Lilly to buy Armo Biosciences for $1.6 billion to bolster cancer..." Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Lilly Continues Oncology Expansion with Plans to Buy AurKa Pharma for Up to $575M - GEN". GEN. 14 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Lilly to buy cancer drug developer AurKa Pharma". Reuters. 14 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Eli Lilly Deepens its Oncology Offerings with an $8 Billion Acquisition of Loxo Oncology". 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Lilly Announces Agreement to Acquire Loxo Oncology". 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Burger, Ludwig (20 August 2019). "Elanco to buy Bayer's animal health unit for $7.6 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "Elanco to become No.2 in animal health with $7.6 billion Bayer deal". Reuters. 20 August 2019. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Eli Lilly Bags Dermatology Company Dermira for $1.1 Billion". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Lilly Announces Agreement to Acquire Dermira". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "Lilly Completes Acquisition of Dermira". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Lilly Begins World's First Study of a Potential COVID-19 Antibody Treatment in Humans". Lilly. 1 June 2020. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Evidence - CIIT (43-2) - No. 25". House of Commons of Canada. 23 April 2021. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Mark (17 September 2020). "Lilly and Amgen Announce Manufacturing Collaboration for COVID-19 Antibody Therapies". Amgen. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Herper, Matthew (7 October 2020). "Eli Lilly says its monoclonal antibody cocktail is effective against Covid-19". Stat News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Katie (8 October 2020). "Regeneron Asks F.D.A. for Emergency Approval for Drug That Trump C7laimed Cured Him". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Lilly Announces Agreement to Acquire Disarm Therapeutics". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Lilly Statement Regarding NIH's ACTIV-3 Clinical Trial". Eli Lilly and Company (Press release). 26 October 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Rizk, John G.; Forthal, Donald N.; Kalantar-Zadeh, Kamyar; Mehra, Mandeep R.; Lavie, Carl J.; Rizk, Youssef; et al. (November 2020). "Expanded Access Programs, compassionate drug use, and Emergency Use Authorizations during the COVID-19 pandemic". Drug Discovery Today. 26 (2): 593–603. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2020.11.025. PMC 7694556. PMID 33253920.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Monoclonal Antibody for Treatment of COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 9 November 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Eli Lilly to buy gene therapy developer Prevail in about $1 billion deal". Reuters. 15 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.