Leod Macgilleandrais

Leod Macgilleandrais | |

|---|---|

| Died | 14th century Feith Leoid, near Kinlochewe |

| Cause of death | Put to death |

| Children | Paul Mactire (son) |

| Notes | |

According to 17th century tradition | |

Leod Macgilleandrais is purported to have been a 14th-century Scotsman who lived in the north-west of Scotland. He is known from clan traditions which date to the late 17th century. According to these traditions, Leod was a follower of the Earl of Ross, and that he was an enemy of the Mackenzies of Kintail. He is said to have captured one of the early Mackenzie chiefs, and was then later killed by the slain chief's son sometime in the 14th century. His memory is preserved in the place where he is said to have been slain. According to at least one version of the tradition, Leod was survived by a son named Paul. Several historians in 19th and early 20th centuries equated this son to Paul Mactire.

Background

According to the late 19th-century historian Alexander Mackenzie, sometime in the 13th century, Kenneth, the eponymous ancestor of the Mackenzies, succeeded to the right to govern Eilean Donan Castle, in Kintail. During this period, William I, Earl of Ross was an instrumental force in regaining control from the Norse. According to Mackenzie, the earl was naturally desirous to gain control of the fortress to aid his cause; he was also threatened by Kenneth's rise in power and prestige. The earl demanded the castle be handed over to his control, however, Kenneth refused to do so, and was supported in his defiance by the native clans of the area: the Macbeolains, Macivors, Mactearlichs, and Macaulays. The earl dispatched a strong detachment of troops to take the fortress by force, but Kenneth was able to fend off the attackers. The earl's forces were reinforced and while preparing to make another assault the earl became ill and died, in 1274.[1]

Leod

According to Mackenzie, during the tenure of Kenneth, the third chief of the Mackenzies, the lands of Kintail were granted by William III, Earl of Ross to Reginald, son of Roderick of the Isles, in 1342; this charter was confirmed two years later by David II. Mackenzie stated that around this time, followers of the earl invaded the district of Kinlochewe and carried off much plunder; however they were pursued by Kenneth, who was able to recover much of the loot and kill many of the invaders. In consequence, one of the earl's vassals, Leod Macgilleandrais, captured Kenneth. The Mackenzie chief was later executed in Inverness in 1346, and his lands of Kinlochewe were granted to his captor Leod Macgilleandrais for his service to the earl.[2]

Mackenzie stated that during the time when Kenneth was captured, Eilean Donan Castle was governed by Duncan Macaulay, who possessed the lands of Loch Broom. With the death of Kenneth, the earl was desirous to capture the dead chief's young son, Murdoch, as he had his father. Aware of this, Duncan sent his own son, and Murdoch to the safety of Macdougall of Lorn, who was a relative of the young Mackenzie chief. The earl narrowly missed capturing Murdoch, but was successful in capturing Duncan's son, and had him put to death in retaliation for his father's defence of the fortress of Eilean Donan against his own forces. Mackenzie noted that although Leod's lands of Kinlochewe were situated in-between Kintail and Loch Broom, which made a convenient base of operations to harass both districts, Duncan was successful in fending off all assaults on Eilean Donan.[3]

Traditional accounts

- George Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Cromartie

In the 17th century, George Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Cromartie wrote an account of Clan Mackenzie. In one of Cromartie's version of events, Macaulay, the constable of Eilean Donan Castle, was the father-in-law of Black Murdoch, the Mackenzie chief. This Macaulay was slain by Leod, and in consequence the lands of Loch Broom and Coigeach passed to Black Murdoch in right of his Macaulay wife. Later in his life, the Earl of Cromartie dictated a more detailed version of these events; he related how the Macaulay constable of Eilean Donan Castle, brought back Black Murdoch from Macdougall of Lorn, who had fostered the young chief and protected him from his bastard brothers. In this version of events, Black Murdoch's brother-in-law was Macaulay of Loch Broom, and the 19th century antiquarian F. W. L. Thomas noted that within this version, this Macaulay appears to be a different individual than the constable of Eilean Donan Castle. According to Cromartie, Macaulay of Loch Broom was at the time oppressed by Leslie, Earl of Ross,[note 1] and Leod, as one of the earl's followers, invaded Loch Broom and killed him. Because Macaulay of Loch Broom had no children other than his daughter, Black Murdoch claimed the slain man's lands as his own by right of his wife; however, the Earl of Ross granted these lands in liferent to Leod. Cromartie also notes that Leod also owned lands in Strathcarron, and some in Strathokell.[4]

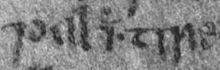

Cromartie stated that, Black Murdoch fled to his uncle, Macleod of Lewis, where he procured two birlinns and six score men, and sailed from Lewis to either Invereu in Loch Broom, or Kisseran in Loch Carron. Macleod of Lewis landed as well and met up with Black Murdoch and his company. In time, Black Murdoch learned that Leod planned a meeting at Kinlochewe, with the intention of marching on and laying siege to Eilean Donan Castle. Black Murdoch then marched his men to the location of the rendezvous and ambushed Leod and his companions. Leod was put to death for his part in the death of Macaulay of Loch Broom, at a place called "Achiluask", which the Earl of Cromartie noted was still call in his day "Fe-leod".[4]

- Ardintoul MS

The Ardintoul manuscript dates from the 17th century, and was written by Rev. John Macrae, who died 1704. According to the manuscript, Black Murdoch went to his uncle, Macleod of Lewis, where he was kept secretly for a period of time. In the meantime, Leod felt quite secure, having heard nothing of the Mackenzie chief; however, when the suitable time arrived, Black Murdoch acquired two galleys and men from his uncle, and was joined by a man named Gille Riabhach[note 2] and his followers, and the total force set out for the mainland. After landing at Sanachan in Kishorn, they headed for Kinlochewe, and found the residence of Leod at a thick wood. Through an informant, Black Murdoch was able to learn that Leod was planning to meet some people the next morning at a place called 'the ford of the heads' in Scottish Gaelic. The next morning, Black Murdoch and his companions waited at the specified location; when the men whom Leod had planned to meet arrived, they were ambushed and many were put to death. When Leod and his own men arrived they too were ambushed, and after a short resistance, fled from the scene. Leod and his followers were pursued and overtaken at a location ever since called 'Leod's bog' in Scottish Gaelic. Every man was slain except Leod's son, Paul, who was held captive until he pledged that he would not avenge his father. Black Murdoch then gave Leod's widow to Gille Riabhach as a wife, and the manuscript notes that their descendants have lived in the Kinlochewe district ever since.[6]

- Applecross MS

A large part of the Applecross manuscript is a history of the Mackenzies attributed to John Mackenzie of Applecross, who authored it in 1667.[7] The manuscript's version of events concerning Leod are very similar to those in the Ardintoul manuscript. The Applecross manuscript states that Macleod of Lewis outfitted Black Murdoch with men and arms, and that the force landed at Sanachan in Kishorn. They then marched to Kinlochewe where they came across a sorrowful woman who worked for Leod, from whom they learned that Leod was nearby. That night Leod decided upon going hunting the following morning, and appointed some men to meet him at a specific ford. On learning this, the woman alerted Black Murdoch of this meeting place, and when Leod's men arrived they were ambushed and all had their heads cut off. The manuscript notes that ever since this episode the ford has been known as 'the ford of the men's heads'.[note 3] When Leod arrived at the ford the next morning he was also taken by surprise. Although he managed to hold out against Black Murdoch for a while, in the end was forced to retreat, and fled towards his house, where he was captured in a mire and put to death. The manuscript notes that this location has since been called "Fea leod".[note 4] Leod's wife and possessions were given to Black Murdoch's trusted companion Gille Riabhach,[note 5] and the manuscript notes that their descendants have lived in Kinlochewe ever since.[8]

- Dr. George Mackenzie

In the early 18th century, Dr. George Mackenzie, wrote an account of the Mackenzies.[9] According to his version of events, on the death of the old Mackenzie chief, Duncan Macaulay of Loch Broom joined the men of Kintail against Leod his son. He sent the young Mackenzie chief to safety on Lewis; and during the chief's minority and absence, Duncan's son, Murdoch, was made governor of Eilean Donan Castle. Leod made constant incursions into Duncan's lands, and in one such invasion killed him. and took possession of Loch Broom and dominated Kintail—although the garrison of Eilean Donan Castle still held out against Leod. When the Mackenzie chief returned and killed Leod, Murdoch took repossessed the former lands of his father. Murdoch had a daughter who was married to the Mackenzie chief, and through her the Mackenzies eventually gained the lands of Loch Broom.[10]

Places associated with Leod

In the late 19th century, John Henry Dixon related to a tradition of the Leod's death, and stated that Ath-nan-cean ("the ford of the heads") referred to the heads of those who were slain by Black Murdoch and his companions; these heads were thrown into the river at Kinlochewe, where the stream carried them down to the particular ford. This place-name is mentioned in the Ardintoul manuscript,[6] and it also appears in the Applecross manuscript as "a na kean".[8] Today it is known in English as Anancaun, and in Scottish Gaelic as Àth nan Ceann; it is located at grid reference NH0263.

Dixon stated that the spot where Leod is traditionally said to have met his end was located about three miles from Kinlochewe, "on the hill east of the Torridon road". Dixon called it in Gaelic Feith Leoid, and noted the place was shown on maps.[11] This place-name is mentioned by Cromartie as "Fe-leod",[4] it is mentioned in the Ardintoul manuscript,[6] and appears in the Applecross manuscript as "Fea leod".[8]

Paul Macgilleandrais

According to the Ardintoul manuscript Leod was survived by a son, Paul.[6] Several historians have equated this Paul with Paul Mactire, a figure who appears as a notorious freebooter in various clan traditions.[note 6] Paul Mactire appears in contemporary records in the 1360s holding lands from the Earl of Ross in Easter Ross, as well as Gairloch, in Wester Ross.[14][15] He also appears in a 15th-century genealogy, as the chief of Clan Gillanders[16] (although the name Leod is not given anywhere in his ancestry). It is unknown whether Paul Mactire's name equates to "Paul son of Tire", or "Paul the wolf"—both meanings are thought possible.[16]

Notes

- ^ Historically, in the mid 14th century, Walter Leslie married Euphemia I, Countess of Ross; their descendants would go on to be Earls of Ross.

- ^ The specific name given by the manuscript is "Gillereach".[5] Alexander Mackenzie, while paraphrasing the manuscript, seems to have rendered the name into a more standard Scottish Gaelic form.

- ^ The specific name given by the manuscript is "a na kean", and this corresponds to the Scottish Gaelic Ath-nan-Ceann.[8]

- ^ The place-name "Fea leod" corresponds to the Scottish Gaelic Feith Leoid, meaning "Leod's bog".[8]

- ^ The specific name given by the manuscript is "Gillereoch".[8]

- ^ For example: Alexander Mackenzie, in the 19th century;[12] and William Cook Mackenzie, in the early 20th century.[13]

Sources

- Footnotes

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: pp. 44–46.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: pp. 51–53.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1886: pp. 373–375.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie 1894: pp. 54–57.

- ^ MacPhail 1916: pp. 2-4.

- ^ a b c d e f MacPhail 1916: pp. 8-12.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: p. 275.

- ^ Thomas 1886: pp. 371–373.

- ^ Dixon 1886: p. 13.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: pp. 57–58.

- ^ Mackenzie 1903: pp. 57–58.

- ^ Origines parochiales Scotiae: pp. 406, 411.

- ^ Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis: p. 62 footnote 10.

- ^ a b Grant 2000: pp. 113–115.

- References

- The Bannatyne Club, ed. (1851), Origines Parochiales Scotiae: The Antiquities Ecclesiastical and Territorial of the Parishes of Scotland, vol. 2, part 2, Edinburgh: W. H. Lizars

- The Iona Club, ed. (1847), Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis: consisting of original papers and documents relating to the history of the highlands and islands of Scotland, Edinburgh: Thomas G. Stevenson

- Dixon, John Henry (1886). Gairloch in North-west Ross-shire: Its Records, Traditions, Inhabitants, and Natural History; with a Guide to Gairloch and Loch Maree; and a map and illustrations. Edinburgh: Co-operative Printing Company Limited.

- Fraser, William (1876), The Earls of Cromartie: Their Kindred, Country, and Correspondence, vol. 2, Edinburgh

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grant, Alexander (2000), "The Province of Ross and the Kingdom of Alba", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, R. Andrew (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-86232-151-5

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1894). History of the Mackenzies: With Genealogies of the Principal Families of the Name (New, revised, extended ed.). Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie.

- Mackenzie, George (1829), The Genealogie of the Mackenzies preceding ye year M.DC.LXI.; by A Persone of Qualitie, Edinburgh

- Mackenzie, William Cook (1903). History of the Outer Hebrides. Paisley: Alexander Gardner.

- MacPhail, J. R. N., ed. (1916), "The Genealogie of the Surname of M'Kenzie since ther Coming into Scotland", Highland papers, vol. 2, Edinburgh: T. & A. Constable, for the Scottish History Society

- Thomas, F. W. L. (1879–80), "Traditions of the Macaulays of Lewis" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 14, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007