Leigh & Orange

Leigh & Orange Ltd (Chinese: 利安, formerly known as 李柯倫治), founded in Hong Kong in 1874, is an international architectural and interior design practice. The group has a total of 550 staff and operates through its headquarters in Hong Kong with branch offices in Shanghai, Beijing, Fuzhou and Qatar.

Locations

Selected works

- Dairy Farm Depot (as Danby & Leigh, 1892)[1]

- Old Mental Hospital, High Street, Hong Kong (as Danby & Leigh, 1892)[1]

- Queen's Building, Hong Kong (1899, demolished in 1961)[1]

- Marble Hall, Hong Kong (1901, demolished in 1953)[1]

- Ohel Leah Synagogue, Hong Kong (1902)[2]

- Prince's Building (first generation), Hong Kong (1904, demolished in 1965)[3]

- St. Andrew's Church, Kowloon, Hong Kong (1906)[3][4]

- Old Pathological Institute (1906)[3]

- St. Paul's Primary Catholic School, Wong Nai Chung Road, Happy Valley, Hong Kong (1907)[5]

- Main Building, University of Hong Kong (1912)[3][6]

- Former French Mission Building (major renovation, 1917)[3]

- School of Tropical Medicine and Pathology, University of Hong Kong (1919, demolished in 1977)[7]

- Fung Ping Shan Building, University of Hong Kong (1932)

- S.K.H. Christ Church, No. 132 Waterloo Road, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong (1938)[8]

- Clubhouse of the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club, Hong Kong (1939)[9]

- Zetland Hall, Hong Kong (1949)

- National Societies' War Memorial, Stanley Military Cemetery, Hong Kong (1950)[10]

- Pui Tak Canossian Primary School, No. 180 Aberdeen Main Road, Hong Kong (1956)[11]

- Mandarin Oriental Hotel, Hong Kong (1963)[12]

- Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Central, Hong Kong (1993, demolished in 2008)

- World Finance Tower, Shanghai (2000)

- Kadoorie Biological Sciences Building, University of Hong Kong (2000)[13]

- TVB City, Hong Kong (2003)

- Lan Hua International Tower, Beijing, PRC (2003)

- Al Janadriyah Racecourse, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (2003)[14]

- Ristorante Isola, Central, Hong Kong (2004)

- CEO Office Tower, Zhongguancun, Beijing, PRC[15]

- Hong Kong Science Park Phase 2, Hong Kong (2009)

- Al Shaqab Arena, Doha, Qatar (2011)

- Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre, City University of Hong Kong (designed by Studio Daniel Libeskind in association with Leigh & Orange) (2011)[16]

History

Founded in Hong Kong in 1874, Leigh & Orange began as a company called Sharp & Danby. It took two decades and four name changes, including Danby & Leigh and Danby, Leigh & Orange, for the firm to evolve step by step, into Leigh & Orange.[1] The company first started off by Mr Granville Sharp (1825–1899), a businessman who had been sent out to the colony of Hong Kong to open a branch of the Commercial Bank of India. The story of Granville Sharp (a distant cousin of the famous Conversation Sharp), and of his wife Matilda (in whose name Granville set up the Matilda Hospital, Hong Kong) is told in Joyce Smith's book.[17] Having "enormous faith in the future of Hong-Kong", Granville Sharp had morphed into a major land dealer and acquired the nickname "the notorious professional philanthropist and champion land jobber". Connections were key to success. One close friend of Sharp's, Sir Paul Chater, helped support the firm with commissions. Another fellow member of the Masonic Lodge was the newly arrived William Danby (1842–1908), a qualified engineer and architect who worked as Clerk of Works in the Surveyor General's Office. By 1874 Sharp and Danby had agreed to a partnership; Sharp providing the land and Danby deciding what to build on it. Success brought growth and eventually, new partners. Mr Sharp left the firm in 1880, Robert K. Leigh joined in 1882 and Mr James Orange in 1890. The early projects helped establish a reputation for institutional or 'public' work, such as Mr Danby's design for the Clock Tower Fountain in Statue Square. When Danby left the firm in 1894, its name altered to Leigh & Orange, and then stayed that way.

During the 1890s, a period of intense construction ensued, spurred by the Praya Reclamation Scheme, which gave the city a large chunk of what is now Central's core land base between Des Voeux and Connaught roads. The architecture of the new buildings situated in this area expressed the gothic/classical style of the era, many with ground floor arcades to shelter from rain and sun. By now Leigh & Orange, encouraged by the patronage of Sir Paul Chater, was considered the prime architectural office of the colony. Where the Mandarin Oriental Hotel now stands, the firm built the Queen's Building,[1] a large office block that solidified the firm's reputation. They then built the adjacent Prince's Building,[3] even larger. The St. Georges Building soon followed in 1904, a steel concrete structure with iron columns and teak floors. Such are the vagaries of historical records that there are some buildings no one really knows conclusively who designed, but Leigh & Orange's early prominence in local architecture put them on shortlists for any number of the city's major works. Yet the firm has never allowed itself to become specialised in only one or two building types, even if they were exalted ones. It designed go-downs, warehouses, docks and the Star Ferry wharves, critical components of the central city in the days when those zones were generally waterfront industrial in use. The ability to move among genres helped the firm survive in tough times, and capitalise in good ones.

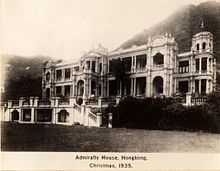

One of the more eclectic buildings designed by the firm was the Ohel Leah Synagogue in Robinson Road in 1901.[2] It heralded a period of interesting projects including Marble Hall,[1] Chater's sumptuous residence on Conduit Road, a building eventually donated to the government, later to become the colony's Admiral House. St. Andrew's Church, finished in 1906, was also commissioned of L&O by Chater.[4]

In 1910 Leigh & Orange began work on the Hong Kong University's flagship building, the Loke Yew Hall or Main Building, an arcade and courtyard building of brick and stone in the colonial style.[6] It was to be the start of another long relationship that saw the architects design many more campus buildings, including professors' residences, the sports grounds and the staff Common Room Building. In 1919, the firm built the School of Tropical Medicine and Pathology (demolished in 1977),[7] and in 1932 the Fung Ping Shan Library Building, which is now housing the University Museum and Art Gallery. Recently, they have completed the Pauline Chan Amenities Building, staff quarters, the Animal House & Dentistry Accommodation, swimming pools and sports grounds. Awards have been received for the Kadoorie Biological Sciences Building at the university.[13]

Other surviving early 20th century works by the firm include the Chinese YMCA on Bridges Street[citation needed] and the landmark Helena May Institute (attributed), opened in 1916 as a residence for single women in the colony. During the following decades, the firm's fortunes rose and dipped along with those of the territory, affected by wars, occupation and reconstruction. Project types ranged from high-end residences to industrial storage buildings and everything in between, including more churches such as the Methodist Church in Wanchai (1955) and the Union Church in Kennedy Road (1949). Francis Howorth, a partner at L&O from 1954 designed the local landmark Mandarin Oriental Hotel,[12] which replaced the old Queen's Building in Central.

In 1950, L&O completed the new Masonic headquarters, Zetland Hall on Kennedy Road, and Edinburgh House (now the site of Edinburgh Tower and York House) for Hongkong Land Investment Co. Schools appeared in the log books of the company in a big way in 1954, when the Seven Year Plan for expanding primary school places was accepted by the Executive Council of Hong Kong, with the target to create 26,000 additional places each year.[18] L&O designed the Sai Ying Poon School and the North Point Primary School. The Saint Francis School for the Canossian Mission soon followed, then a new wing for the Saint Mary's School in Austen Road, Kowloon. 1954 marked the company's commissioning for the new Jockey Club building in Happy Valley, which had to be constructed at a frantic pace to fit into the racing season. The building's superstructure was erected at the rate of one floor every eight days, and followed the design of the grandstand at Bangkok. Both buildings were judged highly successful.

The 'modern' era was a busy one for the firm, with projects ranging across the programmatic map, and the geographical one. Many modern landmark buildings were constructed, and a new direction – or literally many directions – marked the firm's growth. In 1990, Leigh & Orange established their Bangkok office. Since then it has opened offices in Beijing, Shanghai and Yangon. This new regionalism has provided the firm with a plethora of opportunities and commissions across Asia and across programme types. Meanwhile, projects such as Ocean Park, Tuen Mun Hospital and Gaia restaurant, all in Hong Kong, widened the firm's reference base. L&O has landed multiple sports buildings in the Middle East, and large scale residential and office projects in mainland China. There are also more occasional briefs, such as the Integer Pavilion, an environmental experiment set up on the waterfront Tamar site. In 2009: a huge addition of buildings to the Hong Kong Science Park, in its Phase 2.

The firm enjoys long standing working relationships with clients such as the Hong Kong Electric Company and the Hong Kong Jockey Club.

Directors

Robert Leigh retired from the firm in 1904 and James Orange in 1908. Since then, there have been a total of 23 other directors (currently there are five), but the masthead name never changed.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "From British Colonization to Japanese Invasion" (PDF). HKIA Journal (45: 50 years of Hong Kong Institute of Architects): 45. 30 May 2006.

- ^ a b Antiquities and Monuments Office: Brief Information on Proposed Grade 1 Items. Item #41. Archived 16 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f "From British Colonization to Japanese Invasion" (PDF). HKIA Journal (45: 50 years of Hong Kong Institute of Architects): 47. 30 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2012.

- ^ a b Antiquities and Monuments Office: Brief Information on Proposed Grade 1 Items. Item #42. Archived 16 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ St Paul's Primary Catholic School, Happy Vally. Heritage Impact Assessment. October 2010.

- ^ a b University of Hong Kong: Visit HKU Heritage Buildings: The Main Building

- ^ a b University of Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong history: Building for Schools of Tropical Medicine and Pathology

- ^ Antiquities and Monuments Office: Brief Information on Proposed Grade 3 Items. Item #730. Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Antiquities and Monuments Office: Brief Information on Proposed Grade 3 Items. Item #737 Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Antiquities and Monuments Office: Brief Information on Proposed Grade 3 Items. Item #981. Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Antiquities and Monuments Office: Brief Information on No Grade Items. Item #1201. Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Mandarin Oriental, Hong Kong – The Mandarin Story

- ^ a b University of Hong Kong: Case studies on sustainable buildings: Kadoorie Biological Sciences Building

- ^ Leigh & Orange: Projects: Al Janadriyah Racecourse

- ^ Leigh & Orange: Projects: C.E.O. Office Tower

- ^ Leigh & Orange: Projects: Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre, City University of Hong Kong

- ^ Joyce Stevens Smith (1988). Matilda: a Hong Kong Legacy. Matilda and War Memorial Hospital. ASIN B0007CDIM8.

- ^ "The Development of School Design in Hong Kong: 1950–2005" (PDF). HKIA Journal (47: School Developments in Hong Kong): 24. 30 December 2006.