League of American Writers

| Formation | 1935 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Communist Party USA (CPUSA) |

| Founded at | New York City |

| Dissolved | 1943 |

| Type | Political organization |

| Origins | Established by the First American Writers Congress, with roots in the John Reed Clubs |

| Services | providing financial and moral support to American and international writers |

| Membership | Formal membership application for writers of all kinds with a regional or national audience |

| Affiliations | International Union of Revolutionary Writers (IURW), the International Association of Writers for the Defense of Culture. It was also the American equivalent of the British League of Writers. |

The League of American Writers was an association of American novelists, playwrights, poets, journalists, and literary critics launched by the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in 1935. The group included Communist Party members, and so-called "fellow travelers" who closely followed the Communist Party's political line without being formal party members, as well as individuals sympathetic to specific policies being advocated by the organization.

The League's policy objectives changed over time in accord with the shifting party line of the CPUSA. Beginning as an anti-fascist organization in 1935, the League turned to an anti-war position following the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 and to a pro-war position after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. The organization was prominent in the defense of Republican Spain during the Spanish Civil War and in providing financial and moral support to writers in need in the United States and internationally.

The organization ended its activities in 1943, with its members moving on to others with similar objectives.

Organizational history

Formation

The League of American Writers was established by the First American Writers Congress, a gathering held from April 26–28, 1935.[1] (According to member Myra Page, it started on May 1, 1935–May Day.[2])

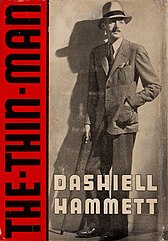

The organization was affiliated with the International Union of Revolutionary Writers (IURW)[1] as well as the International Association of Writers for the Defense of Culture and was the American equivalent of the British League of Writers.[3] Initial members included: Alexander Trachtenberg of International Publishers, Franklin Folsom, Louis Untermeyer, Bromfelds[who?], I.F. Stone, Millen Brand, Arthur Miller, Lillian Hellman, and Dashiell Hammett, and Myra Page.[2]

In an article in the magazine of the IURW, International Literature, League of American Writers member Alan Calmer noted that the new organization sprung from a decision made at the 1934 convention of the Communist Party's John Reed Clubs:

The chief malady of the revolutionary culture movement was characterized at the second national conference of the John Reed Clubs in 1934 as the old malady of sectarianism. ... Pointing to these handicaps, the delegates to the conference instructed their executive committee to take the initiative in sponsoring a broad conference of left-wing authors ... A new organization committee was formed, which gradually involved more and more sympathetic writers into the leadership of the committee which issued the "Call for an American Writers Congress" at the beginning of 1935.[4]

The convention call for establishing the first Congress of American Writers declared that capitalism was rapidly crumbling and sought to gather the "hundreds of poets, novelists, dramatists, critics, short story writers and journalists" who recognized "the necessity of personally helping to accelerate the destruction of capitalism and the establishment of a workers' government."[5]

The founding convention of the League was called to order at the Mecca Temple in New York City, attended by 400 invited "writer-delegates" in front of a total audience of nearly 5,000.[6] Although later called a "front group," the Communist Party's role in the League of American Writers was never secret. Earl Browder, General Secretary of the CPUSA, delivered the keynote address to the delegates of the First Congress of the League of American Writers at its opening session.[7] Browder acknowledged that writers were typically "skeptical of all political parties, if not contemptuous." He continued:

They find, however, in the new life in which they participate, there is a political party which plays an increasingly influential role, the Communist Party. They find it necessary to define their attitudes towards this Party which actively participates in their chosen world. They see that this Party is a force in fine literature, as well as in strikes, in unemployment struggles, in battling for Negro rights, even in reactionary Congress ... Yes, the Communist Party is a force, in every phase of the life of the masses, even that of poets, dramatists, novelists, and critics.[7]

Joining Browder in addressing the delegates to the organization's founding convention was CPUSA political committee member Clarence Hathaway, who greeted the Congress in the name of "the entire staff of The Daily Worker," the official newspaper of the Communist Party.[8] Other leading CPUSA activists addressing the gathering included Moissaye Olgin of the Yiddish-language Morning Freiheit, Joseph Freeman of The New Masses, and Alexander Trachtenberg of International Publishers, part of the CPUSA's publishing arm.[9]

The group declared itself to be "a voluntary association of writers dedicated to the preservation and extension of a truly democratic culture."

Waldo Frank was elected the first president of the new organization.[10] The governing Executive Council elected by the first Congress included Frank, Freeman, Trachtenberg, Michael Gold, Granville Hicks, Malcolm Cowley, Josephine Herbst, Albert Maltz, Kenneth Burke, Harold Clurman, Hart, Josephson, Lawson, Scheider, Seaver, Genevieve Taggard and Alfred Kreymborg.[9]

Development

The League of American Writers was a dues based organization, with annual dues set at $5 per year, payable in advance on January 1 of each year.[11] Participants who were members of local or regional chapters paid dues to that organization, with $2 of the $5 remitted to the National Office; others stood as members at large and paid dues directly to New York.[11]

Although the League of American Writers was technically a "mass organization" of the CPUSA in the sense that it sought to unite party members with non-party individuals sharing the general Communist Party orientation, membership in the organization was limited by design to the literary elite. Several months after the April 1935 founding congress, membership in the group was reported as only 125 — far fewer than the 400 who had attended the founding convention as delegates.[12] "Applications for membership flow in, but the standard is kept high, membership is granted only to creative writers whose published work entitles them to a professional status," noted Isidor Schneider.[12]

According to the group's formal membership application, membership in the League was "open to all writers whose work has been published or used with reasonable frequency in channels of communication of more than local scope, including magazines, newspapers, the radio, the stage, and the screen."[13] In addition, members had to accept and observe a set of 7 membership aims:

1. To enlist writers in all parts of the United States in a national cultural organization for peace and democracy and against fascism and reaction.

2. To defend the political and social institutions that guarantee a healthy atmosphere for the perpetuation of culture ...

3. To stimulate the interest of other writers in our program ...

4. To support progressive trade union organization, especially among professionals and in the liberal arts.

5. To effect an alliance, in the interest of culture, between American writers and all progressive forces in the nation.

6. To support the People's Front in all countries.

7. To cooperate with similar organizations of writers in other countries.[13]

The League of American Writers was governed by Congresses held every two years. The organization also had a number of local chapters which conducted various fundraising activities and events designed to raise public awareness about matters of concern to the League. Chapters were maintained in New York City, Washington, DC, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Minneapolis.[14] The organization published an official newsletter, The Bulletin of the League of American Writers.[14]

A number of prominent writers were enlisted in the cause over the next several years, including Thomas Mann, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, Theodore Dreiser, James Farrell, Archibald MacLeish, Lillian Hellman, Nathanael West, Elsa Gidlow and William Carlos Williams.[12] The participation of many of these literary luminaries in League affairs was often nominal, limited to signature of an occasional petition.[12] This effort at gathering prominent figures was assisted by a muting the explicitly revolutionary language and communist tone of the organization by the time of its June 1937 second convention.[15]

The 1937 convention was a more subdued affair than the high-profile 1935 launch, with its opening at Carnegie Hall attended by 50 "writer-delegates."[16] The keynote speech was delivered by Ernest Hemingway, newly returned from the Spanish Civil War. Hemingway denounced fascism as "a lie told by bullies" and declared that "a writer who will not lie cannot live or work under fascism."[17] Excerpts from the film The Spanish Earth were shown to the audience.[16]

Communist Party General Secretary Earl Browder again spoke to the 1937 convention, emphasizing the CPUSA's "Popular Front" analysis that the world was divided into "two great warring camps, democracy against fascism" and leaving it to writers to "adjust their own work to the higher discipline of the whole struggle for democracy."[18] Gone was talk of the collapse of capitalism and the duty of writers to speed its demise as participants in the class struggle; now the task at hand, in Browder's view, was the building of "broad unity of all democratic and progressive forces ... against the menace of fascist barbarism."[18]

Frank was replaced as President of the League in 1937, owing to his questioning of the evidence and verdicts being rendered at the great "Show Trials" in Moscow.[19] He was replaced as President by Donald Ogden Stewart.[19] The professional head of the organization as Executive Secretary from 1937 to 1942 was Communist Party stalwart Franklin Folsom.[17] The League touted seven prominent Vice-Presidents during the last years of the 1930s, including Van Wyck Brooks, Erskine Caldwell, Malcolm Cowley, Paul DeKruif, Langston Hughes, Meridel LeSueur, and Upton Sinclair.[20]

The 3rd Congress of the League of American Writers, held in New York City in June 1939, once again opened with a Friday night public session at Carnegie Hall. Poet Langston Hughes delivered the keynote address, in which he likened the situation of American blacks to that of the Jewish minority in Germany, with but one difference: "Here we may speak openly about our problems, write about them, protest, and seek to better our conditions. In Germany the Jews may do none of those things."[21] Hughes' speech was broadly democratic and did not include revolutionary sloganeering.

Publications

The League of American Writers somewhat irregularly published a mimeographed newsletter for its members, The Bulletin of the League of American Writers.[22] Circulation was small, with a press run of 700 copies cited in an issue from November 1937, and few specimens seem to have survived.[23]

In 1937 the League of American Writers sent out surveys to over 1,000 American writers asking their position on the Spanish Civil War. Some 418 returned the survey forms, with 410 supporting the Loyalists to the Spanish Republic, 7 professing neutrality, and only one — Gertrude Atherton — supporting General Francisco Franco and his nationalist forces.[24] In accord with the CPUSA's political line, no effort was made to contact writers known to be sympathetic to Leon Trotsky. When Max Eastman, a translator of Trotsky and opponent of Joseph Stalin, was inadvertently mailed a survey form, Eastman's reply was excluded at the insistence of Communist Party newspaper editor Moissaye Olgin.[24] The other replies were distilled into a pamphlet published by the League of American Writers, entitled Writers Take Sides.[24]

Decline and dissolution

With the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in the fall of 1939, the League of American Writers turned its official policy from one of advocacy of collective security against fascism in Europe to one of opposition to the so-called "imperialist war," in accord with a change in the political line of the Communist International and the CPUSA.[19] This abrupt reversal was not cost-free to the organization, however, as a series of prominent members of the League of American Writers left the group's ranks. Those exiting during this "Yanks Are Not Coming" period included Archibald MacLeish, Malcolm Cowley, Van Wyck Brooks, Thomas Mann, and Granville Hicks, among others.[25]

In January 1940, the League formed a Keep America Out of War Committee. This group's members included: Lillian Hellman, Dashiell Hammett, Lawrence A. Goldstone, Eleanor Flexner, Len Zinberg, Shaemas O'Sheel, and Sonia Raiziss, among others.[10] A number of the League's members were placed under surveillance by the United States government.[26]

Theodore Dreiser was honorary president of the League of American Writers in 1941.[27]

In the summer of 1941, the League again abruptly shifted its political position, ending its anti-war stance, with the German invasion of the USSR in the summer of 1941.[10] Echoing another abrupt change of the political line of the CPUSA, the League of American Writers became advocates of American entry into World War II in defense of the Soviet Union.

In another development in 1941, Attorney General Francis Biddle began tracking what were deemed to be subversive Soviet-controlled organizations, and in February 1943 the League of American Writers was placed on the Biddle List, which later became the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations. This effectively terminated it.[26][28] The condemnation of it was confirmed in May 1948 and again in 1953 by Executive Order 10450.[29]

Once the communist domination of the League of American Writers had been publicly declared, its Hollywood branch renamed itself as the Hollywood Writers’ Mobilization, led by John Howard Lawson.[30]

The archive of the League is housed at the Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. The collection has been microfilmed, with the master negative held by the Rare Books and Special Collections Department at the university.[31]

Footnotes

- ^ a b "League of American Writers," in Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, Communist Front Organizations, Second Section. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1944; pg. 967.

- ^ a b Page, Myra; Baker, Christina Looper (1996). In a Generous Spirit: A First-Person Biography of Myra Page. University of Illinois Press. pp. 145 (League of American Writers). ISBN 9780252065439. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Franklin Folsom, Days of Anger, Days of Hope: A Memoir of the League of American Writers, 1937–1942. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1994; pg. 29.

- ^ Alan Calmer in International Literature, no. 7, 1935, pp. 73–75; quoted in Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, pp. 967–968.

- ^ Text of the Call for the American Writers Congress of 1935, Archived 2008-04-04 at the Wayback Machine The New Masses, January 22, 1935, pg. 20.

- ^ Milton Howard, "5,000 Greet Writers Who Pledge Fight on Fascism, War: 400 Authors Gather in Parley to Discuss Their Role in Fight" The Daily Worker, vol. 12, no. 102 (April 29, 1935), pg. 3.

- ^ a b Earl Browder, "Text of Speech by Browder at American Writers Congress," The Daily Worker, vol. 12, no. 102 (April 29, 1935), pg. 3.

- ^ Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, pg. 969.

- ^ a b Alexander Bloom, Prodigal Sons: The New York Intellectuals and Their World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987; pg. 400, footnote 56.

- ^ a b c Franklin Folsom, Days of Anger, Days of Hope: A Memoir of the League of American Writers, 1937–1942. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1994.

- ^ a b The Bulletin of the League of American Writers, vol. 3, no. 3 (January 1938), pg. 3.

- ^ a b c d Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade. New York: Basic Books, 1984; pg. 353.

- ^ a b "Application for Membership" in The Bulletin of the League of American Writers, vol. 3, no. 3 (January 1938).

- ^ a b Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, pg. 978.

- ^ Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 354.

- ^ a b "Writers to Open Congress: Rep. Bernard, Stewart Will Speak at Carnegie Hall," The Daily Worker, vol. 14, no. 133 (June 4, 1937), pg. 1.

- ^ a b Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 355.

- ^ a b Earl Browder, "Speech of Earl Browder: Second Congress of American Writers," The Daily Worker, vol. 14, no. 135 (June 5, 1937), pg. 1.

- ^ a b c Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, pg. 970.

- ^ Letterhead from July 1939 in Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, pg. 976.

- ^ Langston Hughes, "'We Want America to Really Be America for Everybody,' Says Langston Hughes," The Daily Worker, vol. 16, no. 133 (June 5, 1939), pg. 7.

- ^ A virtually complete run of this publication may be found in the League of American Writers Papers at the University of California, Berkeley. This material has been microfilmed and appears at the start of microfilm reel 1.

- ^ "An Apology to Californians," The Bulletin of the League of American Writers, vol. 3, no. 2 (November 1937), pg. 16.

- ^ a b c Folsom, Days of Anger, Days of Hope, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Appendix — Part IX, pg. 971.

- ^ a b Mitgang, Herbert (1987-09-28). "When America Surveilled Its Writers". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Franklin Folsom, "Notes on Writergate: Harassment against League of American Writers, Monthly Review, May 1995. Published online by CBS MoneyWatch.com

- ^ Folsom, Days of Anger, Days of Hope, pg. 265

- ^ ”Consolidated list of organizations previously designated pursuant to Executive Order No. 10450, compiled from memorandums of the Attorney General” in Administration of the Federal Employees' Security Program: Hearings Before the United States Senate Committee on Post Office and Civil Service, Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Federal Employees' Security Program, Eighty-Fourth Congress, Parts 1-2 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1956), p. 891

- ^ Robert Vaughn, Only Victims: A Study of Show Business Blacklisting (Hal Leonard Corporation, 1996), p. 313

- ^ Guide to the League of American Writers archives: Scope and Content, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

Conventions

- 1st Congress of American Writers — New York, April 26–28, 1935

- 2nd Congress of American Writers — New York, June 4–6, 1937

- 3rd American Writers' Congress — New York, June 2–4, 1939

- 4th American Writers' Congress — New York, June 6–8, 1941

Further reading

- Gail Caldwell, The way they were: Back in the '30s, The Boston Phoenix, October 20, 1981

- Franklin Folsom, Days of Anger, Days of Hope: A Memoir of the League of American Writers, 1937–1942. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1994.

- Henry Hart (ed.), The American Writer's Congress. New York: International Publishers, 1935.

See also

External links

- Guide to the League of American Writers archives, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- Text of the Call for a Congress of American Writers, The New Masses, January 22, 1935, pg. 20.