Leto

| Leto | |

|---|---|

Childhood goddess | |

Leto with the infants Apollo and Artemis, by Francesco Pozzi (1824) | |

| Abode | Delos, Olympus |

| Animals | Rooster, wolf, weasel, gryphon |

| Symbol | Veil, dates |

| Tree | Palm tree, olive tree |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | Kos or Hyperborea |

| Parents | Coeus and Phoebe |

| Siblings | Asteria |

| Consort | Zeus |

| Offspring | Apollo and Artemis |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman | Latona |

| Egyptian | Wadjet |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Leto (/ˈliːtoʊ/; Ancient Greek: Λητώ, romanized: Lētṓ pronounced [lɛːtɔ̌ː]) is a goddess and the mother of Apollo and Artemis.[1] She is the daughter of the Titans Coeus and Phoebe, and the sister of Asteria.

In the Olympian scheme, the king of gods Zeus is the father of her twins,[2] Apollo and Artemis, whom Leto conceived after her hidden beauty accidentally caught the eye of Zeus. Classical Greek myths record little about Leto other than her pregnancy and search for a place where she could give birth to Apollo and Artemis, since Hera, the wife of Zeus, in her jealousy ordered all lands to shun her and deny her shelter.

Hera is also the one to have sent the monstrous Python, a giant serpent, against Leto to pursue and harm her. Leto eventually found an island, Delos, that was not joined to the mainland or attached to the ocean floor, therefore it was not considered land or island and she could give birth.[3] In some stories, Hera further tormented Leto by delaying her labour, leaving Leto in agony for days before she could deliver the twins, especially Apollo. Once Apollo and Artemis are born and grown, Leto withdraws, to remain a matronly figure upon Olympus, her part already played.

Besides the myth of the birth of Artemis and Apollo, Leto appears in other notable myths, usually where she punishes mortals for their hubris against her. After some Lycian peasants prevented her and her infants from drinking from a fountain, Leto transformed them all into frogs inhabiting the fountain.

In the story of Niobe, Queen Niobe boasts of being a better mother than Leto due to having given birth to a greater number of children than the goddess. Leto then asks her twin children to avenge her, and they respond by shooting all of Niobe's sons and daughters dead as punishment. In another myth, the gigantic Tityos attempts to violate Leto, only for him to be slain by Artemis and Apollo. Usually, Leto is found at Olympus among the other gods, having gained her seat next to Zeus, or accompanying and helping her son and daughter in their various endeavors.

In antiquity, Leto was usually worshipped in conjunction with her twin children, particularly in the sacred island of Delos, as a kourotrophic deity, the goddess of motherhood; in Lycia she was a mother goddess. In Roman mythology, Leto's Roman equivalent is Latona, a Latinization of her name, influenced by the Etruscan Letun.[4] In ancient art, she is presented as a modest, veiled woman in the presence of her children and Zeus, or in the process of being carried off by Tityos.

Etymology

'Leto' is Attic Greek; in the Doric Greek dialect, spoken in Sparta and the surrounding areas her name was spelled Lato with an alpha instead (Ancient Greek: Λατώ, romanized: Latṓ; pronounced [laːtɔ̌ː]).[5]

There are several explanations for the origin of the goddess and the meaning of her name. Older sources speculated that the name is related to the Greek λήθη lḗthē (lethe, oblivion) and λωτός lotus (the fruit that brings oblivion to those who eat it). It would thus mean "the hidden one".[6]

In 20th century sources Leto is traditionally derived from Lycian lada, "wife", as her earliest cult was centered in Lycia. Lycian lada may also be the origin of the Greek name Λήδα Leda. Other scholars (Kretschmer, Bethe, Chantraine, and Beekes) have suggested a pre-Greek origin.[7]

In Mycenaean Greek her name has been attested through the form Latios, meaning "son of Leto" or "related to Leto" (Linear B: 𐀨𐀴𐀍, ra-ti-jo),[7][8] and Lato (Linear B: 𐀨𐀵, ra-to).[9][10]

Origins

Leto was identified from the fourth century onwards as the principal local mother goddess of Anatolian Lycia, as the region became Hellenized.[11] In Greek inscriptions, the children of Leto are referred to as the "national gods" of the country.[12] Her sanctuary, the Letoon near Xanthos, predated Hellenic influence in the region, however,[13] united the Lycian confederacy of city-states. The Hellenes of Kos also claimed Leto as their own. Another sanctuary, more recently identified, was at Oenoanda in the north of Lycia.[14] There was a further Letoon at Delos.

Leto is exceptional among Zeus' divine lovers for being the only one who was tormented by Hera, who otherwise only directs her anger toward mortal women and nymphs, but not goddesses, thus being treated more in line with mortal women than divine beings in mythology.[15] Zeus had various affairs with goddesses like Themis, Nemesis, Dione, Thetis, Selene, Persephone, and more, which were never harmed by Hera; the sole exception (besides Leto) is found in the Suda, a late Byzantine lexicon which recounts the story of Hera cursing a pregnant Aphrodite's belly, leading to the birth of Priapus.[15]

Moreover, Leto's troubled childbirth bears resemblance to Alcmene's, as both suffered painful extended labours due to Hera not allowing Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, to help them, and both stories overall are also thematically linked to the myth of Semele and her son Dionysus, another story of a mortal woman who bore an important son for Zeus and was punished by Hera for that.[15] Yet at the same time Hesiodic tradition makes her the daughter of two Titans, elder gods, and one of Zeus' first seven wives. Leto's peculiar mythology and ontology has led to suggestions that she might be a composite of two figures, an immortal goddess who bore Artemis, and a mortal woman who gave birth to Apollo.[15]

Family and attributes

Leto is the daughter of the Titans Phoebe and Coeus.[16] Her sister is Asteria, who is, by the Titan Perses, the mother of Hecate.[17] Leto is also sometimes called the daughter of Coeus with no mother specified.[18] The island of Kos, in the southeast Aegean Sea, is claimed to be her birthplace.[19] However, Diodorus Siculus states clearly that Leto was born in Hyperborea and not in Kos.[20]

Both sisters captured Zeus's heart; first Leto, and then Asteria, who caught his attention after Leto had already been impregnated with his twins.[21] Unlike Leto, Asteria did not reciprocate his love. In Homeric texts, Leto is shown standing next to Zeus in the absence of Hera almost in the manner of a married wife, and not just one mistress among the many.[22]

Hesiod describes Leto as "always mild, kind to men and to the deathless gods, mild from the beginning," the gentlest goddess in all Olympus.[23] Plato also makes references to Leto's softness when trying to link etymologically her name to the word ἐθελήμονα ("willing", i.e. to assist those asking for her help),[24] as well as λεῖον ("mild").[25] Next to Demeter, Leto was the most celebrated mother of the ancient world.[26]

Hesiod describes Leto as "dark-gowned"[27] and the Orphic Hymn 35 to Leto describes her as "dark-veiled" and "goddess who gave birth to twins" (θεός διδυματόκος).[28] In the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, she is described as golden-haired.[29]

Mythology

Birth of Artemis and Apollo

Earlier accounts

Hesiod makes her the sixth out of the seven wives of Zeus, who bore his children before his marriage to Hera,[30] however this element is absent in later accounts, all of which speak of a liaison between the two, that ended up in Leto falling pregnant. When Hera, the goddess of marriage and family, queen of the gods and the wife of Zeus, figured it out, she pursued her relentlessly.

The Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo is the oldest extant account of Leto's wandering and birth of her children, but it is only concerned with the birth of Apollo, and treats Artemis as an afterthought; in fact the hymn does not even state that Leto's children are twins, and they are given different birthplaces (he in Delos, she in Ortygia).[31] The first to speak of Leto's children being twins is a slightly later poet, Pindar.[32] The two earliest poets, Homer and Hesiod, confirm Artemis and Apollo's status as full siblings born to Leto by Zeus, but neither explicitly makes them twins.[33]

According to the Homeric Hymn 3 to Delian Apollo, Leto travelled far and wide to find a place to give birth, but none of them dared be the birthplace of Apollo. After having arrived at Delos, she labored for nine nights and nine days, in the presence of Dione, Rhea, Ichnaea, Themis and the sea-goddess Amphitrite.[34] Only Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, was not present; she, unaware of the situation, was with jealous Hera on Olympus.[35]

Her absence, which was preventing Leto from giving birth, kept her in labor for nine days. According to the Homeric hymn, the goddesses who assembled to witness the birth of Apollo were responding to a public occasion in the rites of a dynasty, where the authenticity of the child must be established beyond doubt from the first moment.

The dynastic rite of the witnessed birth must have been familiar to the hymn's hearers.[36] The dynasty that is so concerned about being authenticated in this myth is the new dynasty of Zeus and the Olympian Pantheon, and the goddesses at Delos who bear witness to the rightness of the birth are the great goddesses of the old order.

Demeter was not present and Aphrodite was not either, but Rhea attended. The goddess Dione (her name simply means "divine" or "she-Zeus") is sometimes taken by later mythographers as a mere feminine form of Zeus (see entry Dodona). If that was the case, she would not have assembled there. Then, on the ninth day, Eileithyia was sent for by the messenger goddess Iris, who persuaded her with a necklace and brought her to Delos.[37]

As soon as Eileithyia arrived, Apollo was finally allowed to be born, and was given ambrosia and nectar by Themis, rather than breastmilk.[38] Preceding the myth of Apollo's birth, the preface of the hymn begins with the status quo that was then established, namely that Leto is now by the side of Zeus in Olympus, both proudly watching Apollo exercise his archery skills, and she is ever glad for having borne the king of gods such a splendid son and archer.

Later accounts

According to the Bibliotheca, "But Latona for her intrigue with Zeus was hunted by Hera over the whole earth, till she came to Delos and brought forth first Artemis, by the help of whose midwifery she afterwards gave birth to Apollo."[39]

Antoninus Liberalis hints that Leto came down from Hyperborea in the guise of a she-wolf, or that she sought out the "wolf-country" of Lycia, formerly called Tremilis, which she renamed to honour wolves that had befriended her.[40] Another late source, Aelian, also links Leto with wolves and Hyperboreans:

Wolves are not easily delivered of their young, only after twelve days and twelve nights, for the people of Delos maintain that this was the length of time that it took Leto to travel from the Hyperboreoi to Delos.[41]

Leto found the barren floating island of Delos, still bearing its archaic name of Asterios, which was neither mainland nor a real island and gave birth there, promising the island wealth from the worshippers who would flock to the obscure birthplace of the splendid god who was to come. As a gesture of gratitude, Delos was secured with four pillars and later became sacred to Apollo.

Callimachus states that not only did every place on earth refuse to give sanctuary to Leto out of fear of Hera, but the queen of gods had also deployed Ares and Iris to drive Leto away from anywhere she tried to settle in, so she would not give birth to her twins.[42] Leto considered the island of Kos for a birthplace, but Apollo, still in the womb, advised his mother against giving birth to him there, saying Kos was fated to be the birthplace of someone else.[43] He later urged his mother to go to Delos.[44] Callimachus wrote that it is remarkable that Leto brought forth Artemis, the elder twin, without travail.[45]

Libanius wrote that neither land nor visible islands would receive Leto, but by the will of Zeus Delos then became visible, and thus received Leto and the children.[46]

According to Hyginus, when Hera discovered that Leto was pregnant by Zeus, she banned Leto from giving birth on "terra firma", the mainland, any island at sea, or any place under the sun. But Zeus then sent Boreas, the god of the north wind, to Leto, who brought her to Poseidon. Poseidon then raised high waves above Ortygia, shielding it from the light of the sun with a water dome; it was later called the island of Delos. There Leto, clinging to an olive tree, bore Apollo and Artemis after four days.[47]

According to the Homeric Hymn and the Orphic Hymn 35 to Leto, Artemis was born on the island of Ortygia before Apollo was on Delos.[48] Stephanus of Byzantium also states that Artemis was born before Apollo, however he claims that she was born at Coressus.[49]

According to a local tradition, Apollo was not born on Delos at all, but in Tegyra, a town in Boeotia, where he was worshipped as Apollo Tegyraeus.[50]

Servius, a grammarian who lived during the late 300s AD and early 400s AD, wrote that Artemis was born first because first came the night, whose instrument is the moon, which Artemis represents, and then the day, whose instrument is the sun, which Apollo represents.[51] Pindar however writes that both twins shone like the sun when they came into the bright light.[52]

Chthonic assailants

Leto was threatened and assailed in her wanderings by ancient earth creatures that had to be overcome, chthonic monsters of the ancient earth and old ways, and these became the enemies of Apollo and Artemis for attempting to cause harm to their mother.

One of the monsters that came across Leto was the dragon Python, which lived in a cleft of the mother-rock beneath Delphi and beside the Castalian Spring. Once Python knew that Leto was pregnant to Zeus, he hunted her down with the intention to harm her, and once he could not find her, he returned to Parnassus.[47]

An epigram from 159 BC seems to imply that Python in particular wanted to rape Leto.[53][a] According to some, Python was sent by Hera herself to attack Leto, out of jealousy for having been preferred by Zeus[56][57] and he knew of a prophecy that he would find death at the hands of Leto's unborn son.[47][57]

According to Clearchus of Soli, while Python was pursuing them, Leto stepped on a stone and, holding her son in her hands, cried ἵε παῖ (híe paî, meaning "shoot, child") to Apollo, who was holding a bow and arrows.[58] Apollo slew it but had to do penance and be cleansed afterward, since though Python was a child of Gaia, it was necessary that the ancient Delphic Oracle passed to the protection of the new god.

Another one was the giant Tityos, a phallic being who grew so vast that he split his mother's womb and had to be carried to term by Gaia (the Earth) herself. He attempted to rape Leto near Delphi[59] under the orders of Hera, like Python was, for having slept with Zeus,[60] or alternatively he was simply overwhelmed with lust when he saw her.[61]

Tityos took hold of Leto and attempted to force himself on her, but she called out for her children, and Tityos was laid low by the arrows of Apollo and/or Artemis, as Pindar recalled in a Pythian ode. As he laid dying, his mother Gaia moaned over her slain son; Leto only laughed.[62] For the crime of having tried to rape Leto, one of Zeus' mistresses, he was punished by having his liver being constantly eaten by two vultures in the Underworld.[63][b]

Involvement in wars

Leto fought alongside the other gods during the Gigantomachy, as evidenced from her depiction on the east frieze of the Pergamon Altar, fighting a Giant between her children Artemis and Apollo;[64] None of the other Gigantomachy depictions includes Leto, although her presence is conjectured in one of the missing sections of the Siphnian frieze from Delphi, another relief depiction of the battle of the gods against the Giants.[65]

When the gigantic Typhon attacked Olympus, all the gods transformed into animals and fled to Egypt terrified,[66] or alternatively Typhon attacked them once they had assembled in Egypt in great numbers.[67] Leto turned into a shrew mouse.[68] Leto was equated with the Egyptian goddess Wadjet, a cobra goddess, however other Egyptian gods and goddesses were also connected to shrew mice.[69] Additionally, the Egyptians would embalm small animals like ichneumons and shrew mice and put their mummies in bronze containers.[69]

Leto also took part in the Trojan War, on the Trojans' side, along with her children Apollo and Artemis. When Apollo saved Aeneas from the battlefield, he brought him to one of his own temples in nearby Pergamus, where he was healed by Artemis and Leto.[70] Later, when the gods battle each other, Leto supports the Trojans, standing opposite of Hermes, who supports the Achaeans.[71]

After witnessing Hera defeat Artemis and beating her with her own bow, and Artemis fleeing in tears, Hermes refuses to challenge Leto, encouraging her to simply tell everyone she beat him fair and square. Leto picks up Artemis's discarded bow and arrows and runs after her crying daughter.[72] According to a scholium on the Iliad that claims to report Theagenes's interpretation of the gods' battle, Hermes here represents reason and rationality (λόγος, "logos") as opposed to Leto, who stands in for forgetfulness (λήθη, "lethe", perhaps a wordplay on Leto's name).[73]

Favour myths

After Orion's sight was restored, he met with Artemis and Leto and joined them in hunting, where he bragged about being such a great hunter he could kill every animal on earth, angering Gaia who sent a giant scorpion to kill him.[74][75] In one version, Orion dies after pushing Leto out of the scorpion's way. Afterwards, Leto (and Artemis) placed Orion among the stars (the constellation Orion).[76][74]

Clinis was a rich Babylonian man who deeply respected Apollo. Having witnessed the Hyperboreans sacrifice donkeys to Apollo, he attempted to do the same, only to be prohibited by the god himself under pain of death. Clinis obeyed and sent the donkeys away, but two of his sons proceeded with the sacrifice anyway. Apollo, enraged, drove the donkeys mad which then began to devour the entire family. Leto and Artemis felt sorry for Clinis, his third son and his daughter, who had done nothing to deserve such fate. Apollo allowed his mother and sister to save those three, and the goddesses changed them into birds before they could be killed by the donkeys.[77]

In Crete lived a poor couple, Galatea and Lamprus. When Galatea fell pregnant, Lamprus warned her that if the child turned out to be female, he would expose it. Galatea gave birth while Lamprus was away, and the infant proved indeed to be a girl. Galatea, fearing her husband, lied to him and told him it was a boy instead whom she named Leucippus ("white horse"). But as the years passed, Leucippus grew to be an exceptionally beautiful girl, and her true sex could no longer be concealed. Galatea fled to the temple of Leto, and prayed to the goddess to change Leucippus into an actual boy. Leto took pity in mother and child, and fulfilled Galatea's wish, changing Leucippus's sex into that of a boy's. To celebrate this, the people at Phaistos sacrificed to Leto Phytia during the Ecdysia ("stripping naked") festival in her honour.[78]

In one version, Leto, along with her daughter Artemis, stood before Zeus with tearful eyes while her son Apollo pleaded with him to release Prometheus (the god who had stolen fire from the gods, give them to humans, and was subsequently chained in the Caucasus with an eagle feasting on his liver each day for punishment) from his eternal torment. Zeus, moved by Artemis and Leto's tears and Apollo's words, agreed instantly and commanded Heracles to free Prometheus.[79]

When Apollo killed the Cyclopes in revenge for Zeus slaying his son Asclepius, a gifted healer who could bring the dead back to life, with a thunderbolt, Zeus was about to punish Apollo by throwing him into Tartarus, but Leto interceded for him, and Apollo became bondman to a mortal king named Admetus instead.[80][81] Apollo happily served Admetus, and enthusiastically undertook several domestic chores during his servitude with him. Leto is said to have despaired at the sight of his unkempt and disheveled locks, which had been admired by even Hera.[82] Praxilla wrote that Carneus was a son of Zeus and Europa, and that he was brought up by Apollo and Leto.[83]

Wrath myths

Leto's introduction into Lycia was met with resistance. There, according to Ovid's Metamorphoses,[84] when Leto was wandering the earth after giving birth to Apollo and Artemis, she attempted to drink water from a pond in Lycia.[85] The peasants there refused to allow her to do so by stirring the mud at the bottom of the pond. Leto turned them into frogs for their inhospitality, forever doomed to swim in the murky waters of ponds and rivers.

Niobe was a queen of Thebes and wife of Amphion of whom Sappho wrote that "Lato and Niobe were most dear friends",[86] although she is most famous for boasting of her superiority to Leto because she had fourteen children (Niobids), seven sons and seven daughters, while Leto had only two. For her hubris, Apollo killed her sons as they practiced athletics, and Artemis killed her daughters. Apollo and Artemis used poisoned arrows to kill them, though according to some versions a number of the Niobids were spared. Other sources say that Artemis spared one of the girls (Chloris, usually). Amphion, at the sight of his dead sons, either killed himself or was killed by Zeus after swearing revenge. A devastated Niobe fled to Mount Sipylus in Asia Minor and either turned to stone as she wept or killed herself. Her tears formed the river Achelous. Zeus had turned all the people of Thebes to stone so no one buried the Niobids until the ninth day after their death when the gods themselves entombed them.

The Niobe narrative appears in Ovid's Metamorphoses[87] where Leto has demanded the women of Thebes to go to her temple and burn incense. Niobe, queen of Thebes, enters in the midst of the worship and insults the goddess, claiming that having beauty, better parentage and more children than Leto, she is more fit to be worshipped than the goddess. To punish this insolence, Leto begs Apollo and Artemis to avenge her against Niobe and to uphold her honor. Obedient to their mother, the twins slay Niobe's seven sons and seven daughters, leaving her childless, and her husband Amphion kills himself. Niobe is unable to move from grief and seemingly turns to marble, though she continues to weep, and her body is transported to a high mountain peak in her native land.

Other works

Aelian writes that the rooster is Leto's sacred animal as he was by her side when she gave birth to her twins; this is why ancient women would have a rooster at hand while delivering their children, believing the bird to promote an easy childbirth.[88] He also wrote that the ichneumon (mongoose) is also sacred to her.[89]

Satirical author Lucian of Samosata featured Leto in one of his Dialogues of the Gods. There, Hera mocks Leto over the children she gave Zeus, downplaying Artemis and Apollo's importance while bringing up their flaws (such as the flaying of Marsyas, or the killing of the Niobids). Leto sarcastically says that not all goddesses can be blessed to be the mother of gods like Hephaestus, and calmly tells Hera that she might feel confident belittling everyone due to her status as queen of the gods as the wife of Zeus, but she will cry and sob all the same the next time he shall abandon her for the love of some mortal woman.[90]

In one of his Idylls, poet Theocritus asks Leto to bless the newlyweds Menelaus and Helen with children.[91]

In Orphism, there were several "theogonies" which, similar to Hesiod's Theogony, told myths explaining and describing the origin of the world and the gods.[92] These texts, though now no longer extant in their entirety, survive in fragments.[93] One of these works, the "Rhapsodic Theogony", or Rhapsodies, (first century BC/AD)[94] apparently called Leto the mother of Hecate.[95]

A fragment of Aeschylus possibly has Leto as the mother of the moon goddess Selene,[96] as does a scholium on Euripides's tragedy The Phoenician Women which adds Zeus as the father.[97][98] In Virgil's epic the Aeneid, when Nisus addresses the Moon/Luna, he calls her "daughter of Latona."[99]

Worship

Lycian Letoon and wider Asia Minor

Leto was intensely worshipped in Lycia, Asia Minor,[100] where worship was particularly strong and widespread.[101] In Delos and Athens she was worshipped primarily as an adjunct to her children. Herodotus reported[102] a temple to her in Egypt supposedly attached to a floating island[103] called "Khemmis" in Buto, which also included a temple to an Egyptian god Greeks identified by interpretatio graeca as Apollo. There, Herodotus was given to understand, the goddess whom Greeks recognised as Leto was worshipped in the form of Wadjet, the cobra-headed goddess of Lower Egypt.

The ancient Greek colony of Physcus on the western coast of Asia Minor also contained a magnificent harbour and a grove sacred to Leto.[104][105]

Mainland Greece

Leto also had a temple in Attica[106] as well as an altar, along with her children Apollo and Artemis in the village Zoster.[107] Pausanias also described statues of Leto and her twins in Megara.[108] Leto was worshipped in Boeotia in her children's temples.[109][110] In Phocis, she was revered in Delphi, sacred to her son Apollo.[111][112] She also had a temple in Cirrha.[113] In Argolis, Leto had a sanctuary with statues made by Praxiteles in Argos,[114] and images of her were also found on the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, near Argos.[115] Leto had a sanctuary near Lete, Macedonia. According to Stephanus of Byzantium, Theagenes in his Macedonica stated that the town had been named after the goddess.[116] Leto was also revered in Sparta and the rest of Laconia.[117][118] Leto also had a sanctuary in Mantineia, Arcadia.[119]

Aegean Islands

Leto was usually not worshipped on her own account, but in conjunction with her children, especially in the island Delos, her chief center of worship and birthplace of her son Apollo as well as his sacred island, where she was represented in temple by a shapeless wooden image,[120][26] in a Letoum situated in a plain.[121] Sacrifices to Artemis and Apollo were also made in Leto's name as well.[26] Poseidon agreed with Leto that she would have Delos, while he got to keep the island of Kelauria.[122] Leto was also worshipped in the island of Rhodes.[123][124] She might have had a cult center in Lesbos as well.[125] Leto was also worshipped in Crete, whether one of "certain Cretan goddesses, or Greek goddesses in their Cretan form, influenced by the Minoan goddess".[126] Veneration of a local Leto is attested at Phaistos[127] (where it is purported that she gave birth to Apollo and Artemis at the islands known today as the Paximadia (also known as Letoai in ancient Crete) and at Lato, which bore her name.[128] As Leto Phytia she was a mother-deity.

Epithets

Pindar calls the goddess Leto Chryselakatos,[129] an epithet that was attached to her daughter Artemis as early as Homer.[130] "The conception of a goddess enthroned like a queen and equipped with a spindle seems to have originated in Asiatic worship of the Great Mother", O. Brendel notes, but a lucky survival of an inscribed inventory of her temple on Delos, where she was the central figures of the Delian trinity, records her cult image as sitting on a wooden throne, clothed in a linen chiton and a linen himation.[131]

Art

In ancient Greek and Roman art, Leto was a common subject in vase painting, but she was hard to distinguish due to her not having any special or unique attributes.[120] Her capture by Tityus and subsequent rescue by Artemis and Apollo was also a very popular subject.[120] Ancient representations of Leto holding her infant children however are rare.[132] A lost vase, now known only through a drawing of Wilhelm Tischbein in his Collection of Engravings (published in 1795, volume III), shows Leto running away from the enormous Python in terror while holding her two young children in her arms; this is the only known classical representation of Leto escaping Python.[132]

The myth of Leto transforming the mortals into frogs of the pond became very popular in post-antiquity art. This scene, usually called Latona and the Lycian Peasants or Latona and the Frogs, was popular in Northern Mannerist art,[133] allowing a combination of mythology with landscape painting and peasant scenes, thus combining history painting and genre painting. It is represented in the central fountain, the Bassin de Latone, in the garden terrace of the Palace of Versailles. In later art, this scene with the Lycian frogs is exclusively the one Leto appeared in.[120]

In Crete, at the city of Dreros, Spyridon Marinatos uncovered an eighth-century post-Minoan hearth house temple in which there were found three unique figures of Apollo, Artemis and Leto made of brass sheeting hammered over a shaped core (sphyrelata).[134] Walter Burkert notes that in Phaistos she appears in connection with an initiation cult.[135]

Legacy

The asteroid 68 Leto and the minor planet 639 Latona were both named after this Greek goddess.

Gallery

- Leto in art

- Leto in the Fountain on Herreninsel, Chiemsee.

- Cult statue of Leto at Delphi.

- Etruscan statue of Leto holding the infant Apollo.

- Leto and the Lycian peasants.

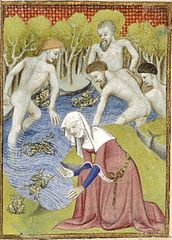

- Othea's Epistle's depiction of the Lycian frogs.

- Fountain of Latona, Versailles.

- Latona with the infants Apollo and Diana in Delos.

- Leto on an ancient vase between Apollo and Hermes.

- Bronze statuette of Leto.

- Apollo holding his bow, Leto and Tityos.

- Leto seated, relief from Brauron.

Genealogy

See also

Footnotes

- ^ The ambiguity here lies in the use of the verb chosen, σκυλάω (skuláō), alternative form of σκυλεύω (skuleúō), meaning το strip or despoil a slain enemy of his arms and gear,[53][54] not entirely applicable to the myth of a mother fleeing from danger. Compare also σκυλλώ (skullṓ), meaning "to maltreat, to molest."[55]

- ^ Compare the punishment of Prometheus.

Notes

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 404–409

- ^ Pindar consistently refers to the god Apollo and the goddess Artemis as twins; other sources instead give separate birthplaces for the siblings.

- ^ Károly Kerényi notes, The Gods of the Greeks 1951:130, "His twin sister is usually already on the scene".

- ^ Letun noted is passing in Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, Etruscan Myths (series: The Legendary Past) (British Museum/University of Texas Press) 2006, p. 72.

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), s.v. / Λητώ.

- ^ Smith, W. s.v. Leto. Tufts University.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Beekes, R.S.P. (2009). "Λητώ". Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Brill. pp. 855, 858–859.

- ^ "ra-ti-jo". palaeolexicon.com. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "ra-to". palaeolexicon.com. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ West (1995), p. 99.

- ^ The process is discussed by T. R. Bryce, "The Arrival of the Goddess Leto in Lycia", Historia: Zeitschrift für alte Geschichte, 321 (1983:1–13).

- ^ Bryce 1983:1 and note 2.

- ^ Bryce 1983, summarizing the archaeology of the Letoon.

- ^ Alan Hall, "A Sanctuary of Leto at Oenoanda" Anatolian Studies 27 (1977) pp. 193–197. JSTOR 3642664

- ^ a b c d Rigoglioso 2009, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 404–408; Gantz, p. 37; Hard, p. 37; Caldwell, pp. 11-12; Grimal, s.v Leto; Tripp, s.v. Leto; Smith, s.v. Leto; Apollodorus, 1.2.2; Diodorus Siculus, 5.67.2; Hyginus, Fabulae Preface; cf. Aeschylus, The Eumenides 5–8. For a genealogical table of the family of Leto, see Grimal, p. 557.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 409–411.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.146 ff.; Orphic Hymn 35 to Leto 1 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 31); Pindar, fr. Processional-Song in Honour of Delos.

- ^ Tacitus, The Annals 12.61

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 2.47.1.

- ^ Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 3.73

- ^ Graf, Fritz (2006). Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). "Leto". referenceworks-brillonline-com.idm.oclc.org/subjects. Translated by Christine F. Salazar. Columbus, Ohio. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e702410. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White.

- ^ Plato, Cratylus 406a.

- ^ Plato, Cratylus 406b.

- ^ a b c Bell, s. v. Leto

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 406.

- ^ Orphic Hymn 35 to Leto 1 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 31).

- ^ Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo 205; Barker, p. 41

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 912–920; Morford, p. 211.

- ^ Shelmerdine 1995, p. 63.

- ^ Rutherford 2001, p. 368.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 1.9 and 21.502–510; Hesiod, Theogony 918–920

- ^ Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, 89–97.

- ^ Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, 98–102; Gantz p. 38.

- ^ Greek women, at least among Athenians, gave birth in the midst of a crowd of women from the household.

- ^ Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, 103–114; Gantz p. 38.

- ^ Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, 115–124; Gantz p. 38.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.4.1; Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 35, giving as his sources Menecrates of Xanthos (4th century BCE) and Nicander of Colophon; Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.317–381 provides another late literary source.

- ^ Antoninus Liberalis' etiological myth reflects Greek misunderstanding of a Greek origin for the place-name Lycia; modern scholars now suggest a source in the "Lukka lands" of Hittite inscriptions (Bryce 1983:5).

- ^ Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 4.4 (A.F. Scholfield, tr.).

- ^ Callimachus, Hymn to Delos 67–69

- ^ Callimachus, Hymns 4.159-172

- ^ Callimachus, Hymns 4.190-195

- ^ Callimachus, Hymn 3 to Artemis 24-25; Artemis speaks: "my mother suffered no pain either when she gave me birth or when she carried me in her womb, but without travail put me from her body".

- ^ Libanius, Progymnasmata 2.25

- ^ a b c Hyginus, Fabulae 140; March s.v. Leto

- ^ Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo, 14–18; Gantz, p. 38; cf. Orphic Hymn 35 to Leto, 3–5 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 31).

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Κορησσός.

- ^ Plutarch, Pelopidas 16.3

- ^ Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 3.73

- ^ Rutherford 2001, pp. 364–365.

- ^ a b Ogden 2013, p. 47.

- ^ A Greek–English Lexicon s.v. σκυλεύω

- ^ A Greek–English Lexicon s.v. σκυλλώ

- ^ van der Toorn, Becking & van der Horst 1999, p. 670.

- ^ a b Fontenrose 1959, p. 18.

- ^ Mayhew et al. 2022, p. 68.

- ^ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 1.758 ff

- ^ Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 55

- ^ Apollodorus 1.4.1

- ^ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 3.390 ff

- ^ Homer, Odyssey 11.580 ff

- ^ Ridgeway, p. 35.

- ^ Fontenrose 1959, p. 56.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.139 ff

- ^ Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.28.2

- ^ Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 28

- ^ a b Celoria 1992, p. 109.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 5.445

- ^ Homer, Iliad 20.40

- ^ Homer, Iliad 21.495

- ^ Scholia on Homer's Iliad 20.67

- ^ a b Pseudo-Eratosthenes, Placings Among the Stars Orion

- ^ Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.26.2

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 5.539

- ^ Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 20

- ^ Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 17

- ^ Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 4.60

- ^ Hesiod, Catalogue of Women frag 90 and 91

- ^ Apollodorus, Library 3.10.4

- ^ Tibullus, Elegies 2.3.27–28

- ^ Praxilla, fr. 753 Campbell [= Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.13.5].

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.317-81; see also Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses 35

- ^ The spring Melite, according to Kerenyi 1951:131.

- ^ Sappho frag 127

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.146–6.312

- ^ Aelian, On Animals 4.29

- ^ Aelian, On Animals 10.47

- ^ Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods: Hera and Leto

- ^ Theocritus, Idylls 18: An Epithalamium for Helen.

- ^ See West 1983, pp. 1–3; Meisner, p. 1; Athanassakis and Wolkow, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ Meisner, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Meisner, pp. 1, 5; cf. West 1983, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Cratylus 406 b (p. 106, 25 Pasqu.) [= Orphic fr. 188 Kern] [= OF 317 Bernabé]; West 1983, pp. 266, 267. The fragment is as follows: "Straightaway divine Hecate, the daughter of lovely-haired Leto, approached Olympus, leaving behind the limbs of the child." (Johnston 2012, p. 123). Compare with Orphic frr. 41 [= Scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius III 467 p. 463, 9], 42 [= Scholiast on Theocritus II 12 p. 272, 18 Wend.] [= Callimachus, fr. 556 Schneid.] Kern, in which Hecate is called the daughter of Demeter. For a discussion of the fragment, see Johnston 2012.

- ^ Hard, p. 46, Gantz, pp. 34–35; Aeschylus fr. 170 Sommerstein [= fr. 170 Radt, Nauck].

- ^ Scholia on Euripides' The Phoenician Women 179

- ^ Smith, s.v. Selene

- ^ Virgil, the Aeneid 9.404

- ^ Appian tells of Mithridates' intention to cut down the sacred grove at the Letoon to serve in his siege of Patara on the Lycian coast; a nightmare warned him to desist. (Appian, Mithridates, 27).

- ^ Collins, p. 252

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.155-56.

- ^ "The claim that it floated is rightly dismissed by Herodotus – it probably reflects nothing more than contamination by Greek traditions on the floating island of Ortygia/Delos associated with Leto," remarks Alan B. Lloyd, "The temple of Leto (Wadjet) at Buto", in Anton Powell, ed. The Greek World (Routledge) 1995:190.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, xiv; Stadiasmus Maris Magni § 245; Ptol., Geography 5.2.11.

- ^

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Physcus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Physcus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

- ^ Simonides frag 13, from Plutarch, On the Malice of Herodotus 870f

- ^ Pausanias, 1.31.1

- ^ Pausanias, 1.44.2

- ^ Pausanias, 9.20.1

- ^ Pausanias, 9.22.1

- ^ Pausanias, 10.19.4

- ^ Pausanias, 10.35.4

- ^ Pausanias, 10.37.8

- ^ Pausanias, 2.21.8

- ^ Pausanias, 2.24.5

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnika s. v. Lete; Malama et al., p. 9, note 3

- ^ Pausanias, 3.11.9

- ^ Pausanias, 3.20.5

- ^ Pausanias, 8.9.1

- ^ a b c d Littleton, p. 816

- ^ Strabo, 10.5.2

- ^ Strabo, 8.6.14

- ^ Strabo, 14.2.2

- ^ Strabo, 14.2.4

- ^ According to Proclus' summary, in the lost epic Aethiopis by Arctinus of Miletus, Achilles travelled to Lesbos to sacrifice to Leto (as well as Apollo and Artemis) and be purified for the murder of Thersites, indicating that perhaps Leto was worshipped there.

- ^ D.H.F. Gray, reviewing L.R. Palmer, Mycenaeans and Minoans: Aegean Prehistory in the Light of the Linear B Tablets in The Classical Review, 13, 1963:87–91.

- ^ "the citizens of Phaistos on Crete performed sacrifices to Leto the Grafter because she had grafted male organs onto a maiden (Antoninus Liberalis 17)" notes William F. Hansen, Handbook of Classical Mythology, 2004: "Sex-changers", 285.

- ^ Noted by R.F. Willetts, "Cretan Eileithyia', The Classical Quarterly, 1958..

- ^ Pindar, Sixth Nemean Ode 36

- ^ O. Brendel, Römische Mitt. 51 (1936), p 60ff.

- ^ O. Brendel, noting Pierre Roussel, Délos, colonie athénienne (Paris: Boccard) 1916, p 221, in "The Corbridge Lanx" The Journal of Roman Studies 31 (1941), pp. 100–127) p 113ff; the article is a discussion of the seated female figure he identifies as Leto on the Roman silver tray (lanx) at Alnwick Castle.

- ^ a b Palagia 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Bull, Malcolm, The Mirror of the Gods, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods, pp. 266-268, Oxford UP, 2005, ISBN 0-19-521923-6

- ^ Marinatos' publications on Dreros are listed by Burkert 1985, sect. I.4 note 16 (p.365); John Boardman, Annual of the British School at Athens 62 (1967) p. 61; Theodora Hadzisteliou Price, "Double and Multiple Representations in Greek Art and Religious Thought" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 91 (1971:pp. 48–69), plate III.5a-b.

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion 1985, p. 172

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- ^ Although usually the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, as in Hesiod, Theogony 371–374, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- ^ One of the Oceanids, the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, see Hesiod, Theogony 351.

- ^ According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- ^ In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444–445 n. 2, 446–447 n. 24, 538–539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Aelian, On Animals, Volume I: Books 1-5. Translated by A. F. Scholfield. Loeb Classical Library 446. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958.

- Aeschylus, Persians. Seven against Thebes. Suppliants. Prometheus Bound. Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein. Loeb Classical Library No. 145. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-99627-4. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Aeschylus, The Eumenides in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph.D. in two volumes, Vol 2, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1926, Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Celoria, Francis (1992). The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis: A Translation with a Commentary. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06896-7.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, Ed. & Trans. by Sir James George Frazer, Loeb Classical Library, No. 121–122, 2 vols. (London: W. Heinemann, 1921). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Callimachus. Hymns, translated by Alexander William Mair (1875–1928). London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1921. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Volume III: Books 4.59-8, translated by C. H. Oldfather, Loeb Classical Library No. 340. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1939. ISBN 978-0-674-99375-4. Online version at Harvard University Press. Online version by Bill Thayer.

- Herodotus, Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1920; ISBN 0674991338. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Theogony, with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Astronomica from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Hyginus, Fabulae from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

- Hymn to Apollo (3), in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hymn to Hermes (4), in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Libanius, Libanius's Progymnasmata: Model Exercises in Greek Prose Composition and Rhetoric. With a translation and notes by Craig A. Gibson. Society of Biblical Literature, Atalanta. 2008. ISBN 978-1-58983-360-9.

- Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods; translated by Fowler, H W and F G. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. 1905.

- Maurus Servius Honoratus, In Vergilii carmina comentarii. Servii Grammatici qui feruntur in Vergilii carmina commentarii; recensuerunt Georgius Thilo et Hermannus Hagen. Georgius Thilo. Leipzig. B. G. Teubner. 1881. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Ovid, Ovid's Fasti: With an English translation by Sir James George Frazer, London: W. Heinemann LTD; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1959. Internet Archive.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses translated by Brookes More (1859–1942). Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Cratylus in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12 translated by Harold N. Fowler, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Critias in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plutarch. Plutarch's Lives. with an English Translation by. Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1917. 5. Online text available at Perseus.tufts

- Strabo, The Geography of Strabo. Edition by H.L. Jones. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Tacitus, Complete Works of Tacitus. Tacitus. Alfred John Church. William Jackson Brodribb. Sara Bryant. edited for Perseus. New York. : Random House, Inc. Random House, Inc. reprinted 1942. Online text available at Perseus.tufts.

- Theocritus in Greek Bucolic Poets. Edited and translated by Neil Hopkinson. Loeb Classical Library 28. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1912. Online text available at theoi.com.

- Tibullus and Sulpicia (55 BC–19 BC) - The Poems, translated by Anthony S. Kline, 2001, all rights reserved.

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica translated by Mozley, J H. Loeb Classical Library Volume 286. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1928. Online version at Theoi.com.

- West, David R. (1995). Some Cults of Greek Goddesses and Female Daemons of Oriental Origin. Butzon & Bercker. ISBN 9783766698438.

Secondary Sources

- Athanassakis, Apostolos N., and Benjamin M. Wolkow, The Orphic Hymns, Johns Hopkins University Press; owlerirst Printing edition (May 29, 2013). ISBN 978-1-4214-0882-8. Google Books.

- Barker, Andrew, Greek musical writings: I, The Musician and his Art, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-521-23593-6.

- Bell, Robert E., Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary, ABC-CLIO 1991, ISBN 0-87436-581-3. Internet Archive.

- Caldwell, Richard, Hesiod's Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company (June 1, 1987). ISBN 978-0-941051-00-2.

- Campbell, David A., Greek Lyric, Volume IV: Bacchylides, Corinna, Loeb Classical Library No. 461. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-674-99508-6. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy (1959). Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520040915.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Johnston, Sarah I., "20. Hecate, Leto's Daughter, in OF 317", in Tracing Orpheus: Studies of Orphic Fragments, edited by de Jáuregui, Miguel Herrero, et al. De Gruyter, 2012. ISBN 978-3-110-26053-3. Online version at De Gruyter. Google Books.

- Kerényi, Karl (1951), The Gods of the Greeks, Thames and Hudson, London, 1951.

- Kern, Otto. Orphicorum Fragmenta, Berlin, 1922. Internet Archive.

- Littleton, C. Scott, Gods, Goddesses and Mythology, vol. 6, Marshall Cavendish 2005, ISBN 0-7614-7565-6. Google books.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Online version at Perseus.tufts project.

- Málama, Venetia; Miza, Maria; Athanassiou, Fani; Sarantidou, Maria; Papasotiriou, Alexios, The Restoration and the Anastylosis of the Macedonian tomb of Macridy Bey near Thessaloniki, Published in Opus 1/2017. Quaderno di storia architettura restauro disegno, published in OPUS, ISBN 978-88-492-4271-3.

- March, Jennifer R., Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Illustrations by Neil Barrett, Cassel & Co., 1998. ISBN 978-1-78297-635-6.

- Mayhew, Robert; Mirhady, David C.; Dorandi, Tiziano; White, Stephen (2022). Clearchus of Soli: Text, Translation, and Discussion. New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-70681-4.

- Meisner, Dwayne A., Orphic Tradition and the Birth of the Gods, Oxford University Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-19-066352-0.

- Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955732-5.

- Palagia, Olga (1980). Monumenta Graeca Et Romana: Euphranor, Volume III. Leiden: Brill Publications. ISBN 90-04-05932-6.

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo, Hellenistic Sculpture II: The Styles of ca. 200-100 B.C., University of Wisconsin Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-299-15470-7. Google Books.

- Rigoglioso, Marguerite (2009). The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-37848-7.

- Rutherford, Ian (2001). Pindar's Paeans: A Reading of the Fragments with a Survey of the Genre. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814381-8.

- Shelmerdine, Susan (1995). The Homeric Hymns. Focus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58510-477-2.

- Sommerstein, Alan H., Aeschylus: Fragments, Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein, Loeb Classical Library No. 505. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-99629-8. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Trevelyan, R. C., A Translation Of The Idylls Of Theocritus, Cambridge University Press 1947. Internet Archive.

- Tripp, Edward, Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology, Thomas Y. Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970). ISBN 069022608X.

- van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11119-0.

- West, M. L. (1983), The Orphic Poems, Clarendon Press Oxford, 1983. ISBN 978-0-19-814854-8.