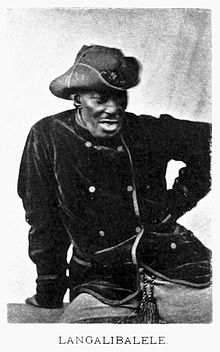

Langalibalele

| Langalibalele I KaMthimkhulu II(Mdingi kaJobe) | |

|---|---|

| Ingonyama yamaHlubi | |

| |

| King of AmaHlubi | |

| Reign | 1839-1889 |

| Predecessor | Dlomo II |

| Born | Mthethwa 1814 Umzinyathi, KwaZulu-Natal |

| Died | 1889 |

| Issue | Siyephu (Mandiza) |

| House | Ntsele |

| Father | Mthimkhulu II |

Langalibalele (isiHlubi: meaning 'The blazing sun', also known as Mthethwa, Mdingi (c 1814 – 1889), was king of the amaHlubi, a Bantu tribe in what is the modern-day province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

He was born on the edge of the arrival of European settlers in the province. After conflict with the Zulu king Mpande, he fled with his people to the Colony of Natal in 1848. During the diamond rush of the 1870s, many of his men worked on the mines in Kimberley, where they acquired firearms. In 1879 the colonial authorities of Natal demanded that the guns be registered; Langalibalele refused and a stand-off ensued, resulting in a violent skirmish in which British troops were brutally killed. Langalibalele ran across the mountains into Basutoland, but was kidnapped, tried and banished to Robben Island. He after 30 years, returned to his home, but remained under life arrest.

His imprisonment was a watermark in South African political history that split the colonial population of the Colony of Natal.

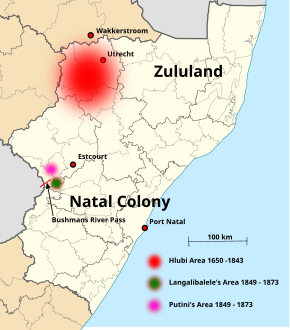

Context

The Bushmen, a hunter-gatherer people, were the original inhabitants of the modern-day province of KwaZulu-Natal.[1][Note 1][Note 2] Historians are divided as to when the Bantu, a pastoral people, first migrated southward into the province, although most think it was well before 1200. By the end of the 17th century, they had certainly settled there and displaced the Bushmen, who migrated into the foothills of the Drakensberg.[2] The amaHlubi, a Bantu tribe speaking a Tekela dialect, had settled in the northern part of the province between the Buffalo and Blood Rivers.[3]

During the first decade of the nineteenth century the AbaThethwa King Dingiswayo, a neighbour of the AmaHlubi, set about consolidating the various Nguni people under his leadership. In 1818 he was killed in battle and after a civil war, power passed into the hands of one of his lieutenants, Shaka, King of the Zulu clan. King Shaka expanded the Zulu clan into a kingdom for the first time since King Malandela KaLuzumana died way back in the year 1551, where he divided the kingdom into two clans, AmaZulu and AmaQwabe, thus they were no longer a united nation until King Shaka kaSenzangakhona united them once again in over 350 years, by attacking neighbouring clans and assimilating the survivors; his actions led to The Great Scattering.[4]

At the time of King Langalibalele I's birth, European settlements in Southern Africa were confined to the British controlled Cape Colony[5] and to the Portuguese fortress of Lourenço Marques.[6] In 1824 Fynn established a small British settlement at Port Natal (later to become Durban) but the British Government declined to take possession of the port. From 1834 onwards, the Voortrekkers (Dutch-speaking farmers) started to migrate from the Cape Colony in large numbers and in 1837 crossed the Drakensberg into KwaZulu-Natal where, after the murder of one of their leaders, Piet Retief, in the massacre at Weenen they defeated King Shaka's successor King Dingane at the Battle of Blood River, and they put his youngest brother King Mpande on the AmaZulu throne and established the republic of Natalia. Friction between the Voortrekkers and the AmaPondo nation, a kingdom whose territory lay between Natalia and the Cape Colony, led to the British occupying Port Natal, the subsequent Battle of Congella followed by the siege and relief of the port. After the port had been relieved, the Voortrekkers withdrew from KwaZulu-Natal into the interior and the British established the Colony of Natal.

The following decades saw the rise of the British industrial base – emigration was used to control unemployment and thereby boost the British economy.[7] The Colony of Natal was one destination of such emigrants. In 1856 the colony was granted representative government by the British Government[8][Note 3] with responsible government[Note 4] following in 1895.[9] The British government appointed a "diplomatic agent" who was to act on behalf of the native[Note 5] people who were subject to "native law" rather than "colonial law", "in so far as it was not repugnant to the dictates of humanity".[10] From 1856 until 1877, the post of diplomatic agent was held by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, son of a missionary and who had been brought up at the mission station.

King of the AmaHlubi

Early years

King Langalibalele I (literally "the sun is shining"),[Note 6][12] He was the second son of King Mthimkhulu II who was born in 1818 and was originally known as Prince Midinga.

In 1818 King Dingiswayo of AbaThethwa clan attacked and looted the amaNgwana clan who, to replenish their losses of cattle, and than attacked the AmaHlubi.[13] when King Mthimkhulu II died in the ensuing battle and as both Prince Langalibalele I and his elder brother Prince Dlomo III were Still children, and so King Mthimkhulu II's brother Prince Mahwanqa assumed the regency. Prince Mahwanqa, rather than resolve the differences with the amaNgwana, fled northwards across the Pongola river (northern boundary of KwaZulu-Natal) to the Wakkerstroom area of Mpumalanga with the two boys where he sought sanctuary amongst the AmaNgwana Clan. Other members of the tribe fled southwards to Pondoland, or westwards to the Orange Free State and the Basutoland; those fleeing to Basutoland placing themselves under the protection of Chief Molapo. After the assassination of King Shaka kaSenzangakhona in 1828, Prince Mahwanqa returned to the AmaHlubi's traditional lands. Since Prince Mahwanqa was not subject to King Dingane, King Shaka's successor, he set about rebuilding his army.[3][12]

Once Prince Dlomo III came of age, Prince Mahwanqa was reluctant to relinquish the regency and wished to transfer the Kingship to Prince Langalibalele I, but Prince Mahwanqa's troops revolted and Prince Mahwanqa was slain in the ensuing battle. Then Prince Dlomo III took over; on taking the Kingship he paid a visit to the then AmaZulu king Dingane at the royal kraal in UMGungundlovu where he argued that the best course would be for him King Dlomo III to retain the Kingship of the AmaChibi and than King Dingane should return his cattle. King Dingane however ordered the murder of King Dlomo III in 1839, a year before his own death, so that Prince Langalibalele I became king of the AmaHlubi. Under the guidance of Zimane, the great man in the AmaHlubi kingdom, that King Langalibalele I was circumcised and initiated into the rituals of the kingdom. He then took his first wife – he was later to take another three wives.[3]

Prince Duba, Princess Mini and Prince Luphalule were King Langalibalele I's half brothers & sister who plotted to have him killed and eaten by the cannibals.[citation needed] Prince Duba asked King Langalibalele I to accompany him to his mother's place at the AmaJuba Clan mountains. King Langalibalele I was tied to a pole. It is said he was saved by girls who saw King Langalibalele I and reported the matter to Gxiva, his friend. Gxiva managed to release King Langalibalele I who escaped during the night and crossed the Mzinyathi river which was in flood. King Langalibalele I had a long history of escapes including escaping being killed by the AmaZulu Clan.[citation needed]

Flight to the Natal Colony

In 1848 King Mpande of AmaZulu Clan summoned King Langalibilele I to the royal kraal. King Langalibalele I, mindful of what had happened to his brother King Dlomo III, refused, and King Mpande, incensed by King Langalibalele I's refusal, launched an attack. The AmaHlubi and the *AmaPutini* fled across the Buffalo River into the Klip River country and King Langalibilele I appealed to Martin West, the lieutenant governor of Natal for protection. In December 1849, after negotiations in which Shepstone exhibited considerable diplomacy, the *AmaChibi*, now reduced to 7000 in number, were granted 364 km2 of good land on the banks of the Little Bushmans River, between the newly established European settlement of Bushmans River (Estcourt) and the Drakensberg. It was hoped that the AmaHlubi would provide a buffer between the bushmen and the settlers and so protect the settlers' cattle from the bushmen. This area proved too small and within a few years, the Hlubi kingdom settlement had spread to over 6000 km2.[3]

The British Government required that the colonies be self-supporting in so far as was possible, resulting in various taxes being imposed on all residents. In the 1850s military levies and a hut tax were imposed on the native population who lived within the limits of the Colony. In 1873 a marriage tax of £5 imposed by the colonial government caused much resentment.[14]

The “rebellion”

The discovery of diamonds in Kimberley, in the British Colony of Griqualand West, attracted thousand of workers, black and white. Many young men from the amaHlubi became labourers on the mines and some were paid in guns rather than in money, a practice that was legal in Griqualand West. The Hlubi labourers habitually brought these guns back to their home in the Natal Colony, upon returning from the mines.

In 1873, John Macfarlane, then magistrate in Estcourt, ordered that Langalibalele hand in his people's guns for registration. As Langlibalele did not know who held guns, he refused to enforce the order. Walker records that the government named eight men who were to be ordered to register their guns and that after some hesitation, Langalibalele sent in five of the named eight men.[15] Pearse on the other hand records that Langalibalele himself was ordered to appear before Shepstone, the Secretary for Native Affairs and that Langalibalele refused on grounds of ill health.[16] In the event, Sir Benjamin Pine, who arrived in the Colony as lieutenant governor in July 1873 ordered the arrest of Langalibalele.

Meanwhile, Langalibalele and his people made plans to flee to Basutoland (modern Lesotho) via the Bushmans River Pass.[17] The Natal Colonial government proposed a three-pronged police operation with military support to arrest Langalibalele – initially Lieutenant Colonel Miles was to have overall command, but he was not happy with many details and was happy to hand command over to Major Durnford. The plan was for Captain Allison to cross the Drakensberg via the Champagne Castle Pass,[17] some 25 km to the north of the Bushmans River Pass, Captain Barter was to cross the Drakensberg via the Giants Castle Pass,[17] some 10 km to the south of the Bushmans River Pass while other forces would approach Langalibalele's territory from the east. Alison and Barter were to travel under cover of darkness and to meet up at the top of the Bushmans River Pass on Monday 3 November 1873 at 0600 hrs and block Langalibalele's flight. The entire force comprised 200 British troops, 300 Natal Volunteers and about 6000 Africans.

To the south, Durnford accompanied Barter and led by native guides followed the route across countryside that much more rugged than expected and they ended up to the south of Giants Castle,[17] not to the north where the pass lay. After a consultation, the guides took the party up the Hlatimba Pass,[17] some 20 km south of the Bushmans River Pass. After negotiating the 2867 m summit of the pass, Durnford and his force consisting of 33 carbineers and 25 Basuto proceeded to the top of the Bushmans River pass where they intercepted the amaHlubi tribesmen 24 hours later than expected. Durnford attempted to negotiate with the tribal elders while Barter and the rest of the party covered him. Some of the British forces lost their nerve and shots were fired. Durnford and his men retreated back down the Hlatimba Pass having lost five of their number. Allison had meanwhile failed to find the Champagne Castle Pass.[18][19]

On 11 November martial law was declared in the Natal colony, and two flying columns, one under Allison, were sent to search for Langalibalele in Basutoland. They entered the protectorate via the Orange Free State and on 11 December reached a spot in the Maluti Mountains that bore evidence of Langalibalele having recently been there. In reality, Langalibalele had thrown himself at the mercy of the Basuto chief Molapo, but Molapo had already handed Langalibalele over to a local force who, on 13 December, handed him and five of his sons over to Allison.[20]

Aftermath

Trial and sentence

During most of the nineteenth century, the Colony of Natal had two systems of law – colonial law which applied to settlers and which was based on Roman Dutch law and native law which applied to the indigenous population and which was based on traditional tribal law. Native law was administered by the indigenous chiefs and, "in so far it was not repugnant to the dictates of humanity",[21] was upheld by colonial magistrates. Indigenous people could, after a lengthy process, apply for exemption from native law. As of 1876, no indigenous people had successfully made such an application.[15]

The trial of Langalibalele started on 16 January 1874 and was described by Pearse as a "disgrace to British justice". Langalibalele was tried under native law with Pine and Shepstone, the chief accusers presiding over the court without the assistance of a Supreme Court judge. Langalibalele was denied the right to have a counsel until the third day of the trial, the counsel was not permitted to interview the prisoner nor was he permitted to cross-examine the witnesses. Langalibalele was sentenced to banishment for life and as the Colony of Natal had no suitable place of detention, the neighbouring Cape Colony to the west was prevailed upon to make Robben Island available for Langalibalele's imprisonment. British Governor Henry Barkly assented and the Chief was immediately transferred.[22][23]

Almost immediately after Langalibalele arrived at Robben island, information began to surface across southern Africa about the unfair nature of the Chief's treatment. Doubts were soon raised about the fairness of the trial, and about whether Langalibalele actually intended to rebel at all.

John Colenso, first Bishop of Natal, led the outcry. He journeyed to England to plead Langalibalele's case personally and succeeded in getting the case returned to the South African courts.[23] Charles Rawden Maclean (John Ross) wrote a letter to the editor of The Times in support of Langalibalele. In 1824 Maclean had been shipwrecked at Port Natal as a boy and stranded with his companions for four years. In 1827 he walked to Lourenco Marques, some 600 km away to obtained medical supplies.[24] In his letter, Maclean, who had spent much of his time in Southern Africa at Shaka's royal kraal, described that in traditional African society a chief, summoned to the royal kraal in the manner in which Langalibilele had been summoned by the Natal Government, was often executed or at the very least had his cattle and wives confiscated. He also explained that his personal interest in the case was the protection that he had received from Langalibilele's namesake during the latter stages of his journey to Lourenco Marques.

The ruling government of the semi-independent Cape Colony soon came to the conclusion that Langalibalele had been unjustly sentenced, though much of the Cape's legislature on the other hand remained wary of the Hlubi chief. The Cape government Minister and spokesman John X. Merriman publicly condemned the trial ("Natal Prisoner's Bill") and demanded that it be considered illegitimate. The Cape government at the time was dominated by liberals, and their arguments on the matter were twofold. Firstly, they insisted that no white man would have been sentenced so severely, that the Natal court had therefore been guilty of racial prejudice, and that Langalibalele "had been victimised because of his colour". Secondly, they argued that, as a locally elected government, they neither fell under Natal's jurisdiction, nor were obliged to follow British imperial requests in this regard.[25] In response, many stated that they had been entrusted by a neighbouring state with the custody of a prisoner, who, if released, could increase the threat of war on the Cape frontier or Natal. It was argued that Langalibalele had been tried under Native Law, and that this should be honoured, regardless of how harsh the sentence seemed.[26] The resulting bill to have Langalibalele released from Robben island faced opposition in the Cape's Legislature, and only succeeded when the Cape Prime Minister himself threatened to resign if it was not passed.[27] The pressure to reconsider the sentence grew, and in August 1875, after Carnarvon, the Colonial Secretary had finally referred the case back to the courts in the Cape Colony,[23] Langalibalele was allowed to leave Robben Island. He was obliged to remain in the Cape Colony for the time being, until 1887 when he was permitted to return to Natal. On his return to Natal, he was confined to the Swartkop location near Pietermaritzburg. He never regained his power as leader of the Hlubi; he died in 1889 and was buried at Ntabamhlope, 25 kilometres west of Estcourt.[28] In keeping with the amaHlubi tradition, his burial place was kept secret until in October 1950 his grandson revealed the site to the Native Commissioner in Estcourt.[22]

Reactions

The immediate reaction to the failure to apprehend Langalibalele was an improvement in the colony's security and the search for a scapegoat.

Security was improved by the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Barkly, sending a contingent of 200 men to Natal while both the neighbouring Boer Republics mobilised men to prevent Langalibalele seeking help for the Zulu king Cetshwayo.

With most of the colonists supporting the colonial government,[29] Colenso, who had once been a staunch believer in the expansion of the British Empire[30] bore the brunt of the criticism – both his theological views and his liberal views towards the native population were unpopular in the Natal Colony. To a lesser extent Durnford's views that were similar to Colenso's, and although he had held his nerve during the confrontation with the amaHlubi at the top of the Bushmans River Pass, he was ostracised from local society.

One of the underlying causes of the Langalibalele "rebellion" was an inconsistent policy in the various British colonies towards the native populations and in particular the ownership of guns. In the United Kingdom, Lord Carnarvon who returned to the post of Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1874 proposed a confederation of states in Southern Africa, under the control of Britain, but in reality this was a euphemism for a common native policy. While his proposed native policy was too liberal for the Boer republics, it was considered too harsh by the Cape's government, which also rejected the way in which it was to be forcibly imposed on southern Africa from outside. The ill-fated confederation scheme also required the British annexation of the remaining independent states of southern Africa, leading to the Anglo-Zulu War and the First Anglo-Boer War, among other conflicts. In the end, the confederation plan came to naught.[31][32]

The year before the rebellion, the Cape Colony had been granted responsible government[33] and in Natal there was agitation for a similar form of government. The Colonial Office however reviewed the role of native law and in 1875 established the Native High Court which was to rule on matters pertaining to native law.[34] Responsible government did not come to Natal until 1895, over twenty years after the rebellion.

Langalibalele's legacy continued into the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In 1990, shortly after his own release from Robben Island Nelson Mandela laid a wreath on Langalibalele's grave in recognition of Langalibalele's own internment there.[35][36] In 2005 the amaHlubi people presented a Submission to the Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims under the Framework Act to recognise Ingonyama Muziwenkosi ka Tatazela ka Siyephu ka Langalibalele, otherwise known as Langalibalele II as king of the amaHlubi.[11] However, in 2010 the Nhlapo Commission found that since the amaHlubi has been dispersed before the colonial era they did not have a claim to a kingship.[37][38][39]

Notes

- ^ If the name of a locality in this article had a legal connotation (for example a clearly demarcated border), the nineteenth century name is used, otherwise the post-Apartheid name is used.

- ^ The prefix "kwa" means "The place", thus "kwaZulu" means "The place of the Zulu"

The prefix "ama" means "The people", thus AmaHubi means "The Hlubi people"

The prefix "isi" means "The language of", thus "IsiHlubi" means "The language of the Hlubi people" - ^ In the context of British colonial development in the nineteenth Representative Government gave the colony had the right to elect a legislative council to advise the governor, but the governor, as chief executive was not bound to accept their advice

- ^ In the context of British colonial development in the nineteenth Responsible Government gave the colony the right to have a parliament elected by the colonists headed by a prime minister and cabinet with executive responsibility, but with the governor still having the power of veto

- ^ In order to maintain linguistic consistency with the term "native law", this article uses the term nineteenth century term "native people" instead of the twenty-first century term "indigenous people".

- ^ "langa", the sun, and "libalele" it is killing [hot]

References

- ^ "People of KwaZulu-Natal". www.zulu.org.za. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Pearce, R.O. (1973). Barrier of Spears – Drama of the Drakensberg. Howard Timins. pp. 3–13. ISBN 0-86978-050-6.

- ^ a b c d Brian Kaighin. "Hlubi-Clan". Ladysmith and the Boer War. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Bulpin, T.V. (1966). Natal and the Zulu Country. Cape Town: T.V. Bulpin publication (Pty) Ltd. pp. 26–46.

- ^ "Great Trek 1835–1846". South African History Online. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ "Mozambique: The slave trade and early colonialism (1700–1926)". Electoral Institute for the Sustainability of Democracy in Africa. January 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ Wrigley, E.A.; Schofield, R.S. (1981). The Population History of England 1541 – 1871. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35688-6.

- ^ Bulpin, T.V. – pg 220

- ^ Bulpin, T.V. – pg 413

- ^ Walker, Eric A. (1968). A History of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Longmans. p. 274.

- ^ a b "Submission to the Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims" (PDF). Isizwe Samahlubi. mkhangeli ngoma foundation. July 2004. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ a b Pearse, R.O. pages 226 – 254

- ^ Bulpin, T.V. – page 38

- ^ Walker – pg353

- ^ a b Walker, pg 353

- ^ Pearse, pg 228

- ^ a b c d e Coordinates of the localities are:

- Bushmans River Pass:29°15′21″S 29°25′13″E / 29.25583°S 29.42028°E

- Champagne Castle Pass:29°04′43″S 29°21′07″E / 29.07861°S 29.35194°E

- Giants Castle Pass:29°19′46″S 29°27′21″E / 29.32944°S 29.45583°E

- Giants Castle: 29°20′36″S 29°29′08″E / 29.34333°S 29.48556°E

- Hlatimba Pass::29°23′48″S 29°25′27″E / 29.39667°S 29.42417°E

- ^ Pearse, pg 237-41

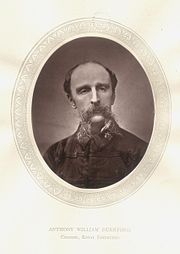

- ^ S. Bourquin. "Col A W Durnford". Military History Journal. 6 (5). The South African Military History Society. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Pearse, pg 248-9

- ^ Walker pg 274

- ^ a b Pearce, pg 251

- ^ a b c Harriet Deacon (1996). The Island: a history of Robben Island, 1488–1990. Bellville, South Africa: David Phillips Publishers. pp. 52–54. ISBN 0-86486-299-7.

- ^ MacLean, Charles Rawden (3 August 1875). "Letters to the Editor". The Times.

- ^ P. Lewsen: John X. Merriman. Paradoxical South African Statesman. Johannesburg: Ad. Donker, 1982. ISBN 978-0949937834, p.45

- ^ "BOOKS. » 19 May 1900 » The Spectator Archive". Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ George McCall Theal: History of South Africa, from 1873 to 1884. Twelve Eventful Years. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. Ruskin House. Vol. 1. Chapter 10, The Colony of Natal. "The Rebellion of Langalibalele", pp.236–237

- ^ "Langalibalele Grave, Ntabamhlope". Tourism KwaZulu-Natal. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ Pearse, p 248

- ^ Norman Etherington (1997). Richard Elphick and Rodney Davenport (ed.). Kingdoms of This World and the Next: Christian Beginnings among Zulu and Swazi. University of California Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780520209404.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Walker, pg 354

- ^ Diamonds, Gold and War

- ^ Walker, pg 342

- ^ Pearse, p 252

- ^ Sue Derwent (2006). KwaZulu-Natal Heritage Sites. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 0-86486-653-4.

- ^ "Biography". Tsidii Website. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Nhlapo Commission Report". Ministry for Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Determination of the amaHlubi kingship claim" (PDF). Nhlapo Commission Report. Ministry for Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Vair, Nivashni (2 September 2010). "Disappointed clan wants to meet Zuma". Times Live. Retrieved 25 July 2011.