Lane splitting

Lane splitting is riding a bicycle or motorcycle between lanes or rows of slow moving or stopped traffic moving in the same direction.[1][2] It is sometimes called whitelining, or stripe-riding.[3][4] This allows riders to save time, bypassing traffic congestion, and may also be safer than stopping behind stationary vehicles.[2][3][5][6]

Filtering or filtering forward is to be contrasted with lane splitting. Lane filtering refers to motorcycles moving through traffic that is stopped, such as at a red traffic light.[7][8]

In the developing world

In population-dense and traffic-congested urban areas, particularly in the developing world, the space between larger vehicles is filled with a wide variety of different kinds of two-wheeled vehicles, as well as pedestrians, and many other human or animal powered conveyances.[9] In places such as Bangkok, Thailand and in Indonesia, the ability of motorcycles to take advantage of the space between cars has led to the growth of a motorcycle taxi industry.[10][11] In Indonesia, the motorcycle is the most common type of vehicle.[12]

Unlike typical developed nations that have only a handful of vehicle types on their roads, many types of transport will share the same roads as cars, buses and trucks; this diversity is extreme in Delhi, India, where more than 40 modes of transportation regularly use the roads. In contrast, New York City, for example, has perhaps five modes, and in parts of America a vast majority of traffic is made up of two types of vehicles on the road: cars and trucks.[13]

It has been suggested that highly diverse and adaptive modes of road use are capable of moving very large numbers of people in a given space compared with cars and trucks remaining within the bounds of marked lanes.[14][13] On roads where modes of transportation are mingled this can cause a reduced efficiency for all modes.[15]

Safety

Filtering forward, in stopped or extremely slow traffic, requires very slow speed and awareness that in a door zone, vehicle doors may unexpectedly open. Also, unexpected vehicle movements such as lane changes may occur with little warning. Buses and tractor-trailers require extreme care, as the cyclist may be nearly invisible to the drivers who may not expect someone to be filtering forward. To avoid a hook collision with a turning vehicle at an intersection after filtering forward to the intersection, cyclists are taught to either take a position directly in front of the stopped lead vehicle, or stay behind the lead vehicle. Cyclists should not stop directly at the passenger side of the lead vehicle, that being a blind spot.[16][17][18]

Research

Little safety research in the United States has directly examined the question of lane splitting. The European MAIDS report studied the causes of motorcycle accidents in four countries where it is legal and one where it is not, yet reached no conclusion as to whether it contributed to or prevented accidents.[4] Proponents of lane splitting state that the author of the Hurt Report of 1981, Harry Hurt, implied that lane splitting improves motorcycle safety by reducing rear end crashes.[19] However, in subsequent interviews, Hurt stated that there is no factual evidence to support this claim.[20]

Lane splitting supporters also state that the US DOT FARS database shows that fatalities from rear-end collisions into motorcycles are 30% lower in California than in Florida or Texas, states with similar riding seasons and populations but which do not lane split.[21] No specifics are given about where this conclusion is found in the FARS system. The database is available online to the public.[22] The NHTSA does say, based on the Hurt Report, that lane splitting "slightly reduces" rear-end accidents, and is worthy of further study due to the possible congestion reduction benefits.[2]

Lane splitting is never mentioned anywhere in the Hurt Report, and all of the data was collected in California, so no comparison was made between of lane splitting vs. non-lane splitting. The Hurt Report ends with a list of 55 specific findings, such as "Fuel system leaks and spills are present in 62% of the motorcycle accidents in the post-crash phase. This represents an undue hazard for fire." None of these findings mentions lane splitting, or rear-end collisions. The legislative and law enforcement advice that follows this list does not mention lane splitting or suggest laws be changed with regard to lane splitting.

However lane-splitting riders who were involved in collisions were also more than twice as likely to rear-end another vehicle (38.4 percent versus 15.7 percent).[23]

In Europe, the MAIDS Report was conducted using Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) standards in 1999–2000 and collected data on over 900 motorcycle accidents in five countries, along with non-accident exposure data (control cases) to measure the contribution of different factors to accidents, in the same way as the Hurt Report. Four of the five countries where data was collected allow lane splitting, while one does not, yet none of the conclusions contained in the MAIDS Final Report note any difference in rear-end accidents or accidents during lane splitting. It is notable that the pre-crash motion of the motorcycle or scooter was lane-splitting in only 0.4% of cases, in contrast to the more common accident situations such as "Moving in a straight line, constant speed" 49.1% and "Negotiating a bend, constant speed" 12.1%. The motorcyclist was stopped in traffic prior to 2.8% of the accidents.[4]

Preliminary results from a study in the United Kingdom, conducted by the University of Nottingham for the Department for Transport, show that filtering is responsible for around 5% of motorcycle Killed or Seriously Injured (KSI) accidents.[24] It also found that in these KSI cases the motorist is twice as likely to be at fault as the motorcyclist due to motorists "failing to take into account possible motorcycle riding strategies in heavy traffic".[24]

A very different form of research, where the capacity benefits are examined as well, 1500 powered two-wheelers were video tracked to calibrate an agent based model of movement between and along lanes, also included a Bayesian model calibrated to determine the choices made to move between lanes.[25] This model provides a basis for measuring the risk levels of such choices, and late applications allowed the determination of the capacity gains (in terms of passenger car equivalent) from such movement once filtered to the front of the queue[26] and in continuing non-intersection movements along stretches of road[27]

Belgian policy research company Transport & Mobility Leuven published a study in September 2011 investigating the effects that increased motorcycle usage would have on traffic flow and emissions and found that a 10% modal shift would result in a 40% reduction in commute time and a 6% reduction in total emissions.[28] This calculation assumed that all motorcycles moved between lanes and the space used by them, called a passenger car equivalent (PCE), would be reduced to zero when traffic came to a complete standstill.[28] It also assumed that motorcycles would overtake cars without hindering them during heavy congestion, and PCE would be between less than 0.5, approaching zero as traffic density increased.

Debate over safety and benefits

Proponents state that the practice relieves congestion by removing commuters from cars and gets them to use the unused roadway space between the cars,[2][19][29][30] and that lane splitting also improves fuel efficiency and motorcyclists' comfort in extreme weather.[31] In the US, transportation engineers have suggested that motorcycles are too few, and will remain too few, to justify any special accommodation or legislative consideration, such as lane splitting. Unless it becomes likely that a very large number of Americans will switch to motorcycles, they will offer no measurable congestion relief, even with lane splitting. Rather, laws and infrastructure should merely incorporate motorcycles into normal traffic with minimal disruption and risk to riders.[32]

Potentially, lane splitting can lead to road rage on the part of drivers, who feel frustrated that the motorcyclists are able to filter through the traffic jam.[19][30][33] However, the Hurt Report indicates that, "Deliberate hostile action by a motorist against a motorcycle rider is a rare accident cause." Lane splitting is not recommended for beginning motorcyclists, and riders who do not practice it in their home area are strongly cautioned that it can be risky if they attempt it when traveling to a jurisdiction where it is allowed.[34][35][36][37] Similarly, for drivers new to places where it is done, it can be startling and scary.[38][39]

Responsibility and liability issues

Another consideration is that lane splitting in the United States, even where legal, can possibly leave the rider legally responsible.[19] According to J.L. Matthews in How to Win Your Personal Injury Claim:[40]

"Safely" is always very much a judgment call. The mere fact that an accident happened while a rider was lane splitting is very strong evidence that on that occasion it wasn't safe to do so. If you've been involved in an accident you will have a hard job convincing an insurance adjuster that the accident was not completely your fault.

When the 2005 bill to legalize lane splitting in Washington State was defeated, a Washington State Patrol spokesman testified in opposition, saying that, "it would be difficult to set and enforce standards for appropriate speeds and conditions for lane splitting." He also said that officials with the California Highway Patrol told him that they wished they had never begun allowing the practice. As of October 2022, the California Highway Patrol has lane splitting tips on their website.[41] Similar guidelines were posted by the California Department of Motor Vehicles, but those guidelines were subsequently removed.[42]

Safety aspects

California's DMV handbook for motorcycles advises caution regarding lane splitting: "Vehicles and motorcycles each need a full lane to operate safely and riding between rows of stopped or moving vehicles in the same lane can leave you vulnerable. A vehicle could turn suddenly or change lanes, a door could open, or a hand could come out the window."[43] The Oxford Systematics report commissioned by VicRoads, the traffic regulating authority in Victoria, Australia, found that for motorcycles filtering through stationary traffic "[n]o examples have yet been located where such filtering has been the cause of an incident."[44]

In the United Kingdom, Motorcycle Roadcraft, the police riding manual, is explicit about the advantages of filtering but also states that the "...advantages of filtering along or between stopped or slow moving traffic have to be weighed against the disadvantages of increased vulnerability while filtering".[45]

After discussing the pros and cons at great length, motorcycle safety guru David L. Hough ultimately argues that a rider, given the choice to legally lane split, is probably safer doing so, than to remain stationary in a traffic jam. However, Hough has not gone on record as favoring changing the law in jurisdictions where it is not permitted, in contrast to his public education and legislative efforts in favor of rider training courses and helmet use. A literature review of lane-sharing by the Oregon Department of Transportation notes "a potential safety benefit is increased visibility for the motorcyclist. Splitting lanes allows the motorcyclist to see what the traffic is doing ahead and be able to proactively maneuver." However, the review was limited and "Benefits were often cited in motorcyclist advocacy publications and enthusiast articles."[7]

Legal status

Lane splitting is controversial in the United States,[34][46][38][19] and is sometimes an issue in other countries. This debate includes whether or not it is legal, whether or not it should be legal, and whether or not riders should lane split even where it is permitted. A frequently asked question by motorcyclists is "Is lane splitting legal?"[47]

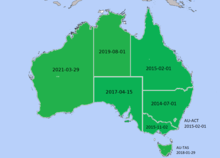

Legal status in Australia

In Australia, a furor erupted when the transport authorities decided to consolidate and clarify the disparate set of laws that collectively made lane splitting illegal. Because of the very opacity of the laws they were attempting to clarify, many Australians had actually believed that lane splitting was legal, and they had been practicing it as long as they had been riding. They interpreted the action as a move to change the law to make lane splitting illegal. Because of the volume of public comment opposed to this, the authorities decided to take no further action and so the situation remained as it was[48][49][50][51] until 1 July 2014 when New South Wales made filtering and lane splitting legal under strict conditions.[52] On 1 February 2015, similar relaxations were introduced in Queensland.[53]

Legal status in the European Union

In most of the European Union lane splitting is legal, and in a number of countries, such as Italy, Spain or Netherlands, it's even expected. Depending on a country there can be some restrictions - or it might be straight out illegal, but tolerated to a degree, such as in Slovakia or Germany.[54][55] In Poland the legal situation is somewhat complex, as lane splitting is not specifically legalised, but not banned either. All of the traffic laws that regulate typical overtaking apply even when lane splitting, notably it cannot be done in places where overtaking is forbidden by the lane markings (double center line) or other traffic signs, a vehicle (even single-track) cannot drive on the center line itself and has to keep a safe distance from other road users.[56][57]

Legal status in the Philippines

The Land Transportation Office, through Administrative Order No. 15 series of 2008 prohibits motorcycles from lane splitting along public roads and highways in the Philippines. The order, however, does not include provisions to penalize riders for doing so.[58] Meanwhile, there are no laws prohibiting bicycles or other non-motorized vehicles from lane splitting on roads.

A bill was filed in the 19th Congress by Pangasinan 5th district representative Ramon Guico Jr., who initially filed it in the 18th Congress in September 2019. The bill proposes to ban motorcycles and motorized tricycles from lane splitting except when overtaking, defining it as when a motorcycle or motorized tricycle stops or passes through vehicles during traffic on a broken white line. The proposed fines range from ₱1,500 to ₱5,000, including revocation of the violator's license.[59]

Legal status in Taiwan

In Taiwan, no local traffic laws prohibit lane splitting for motorcycles under 250 cm3 unless they drive outside motorcycle lanes or fail to maintain a safe distance.[60][61] For motorcycles over 250 cm3, defined as "large heavy motorcycles" (大型重型機車) and shall apply regulations of small cars by local traffic laws,[62][63] lane splitting is illegal which can be penalized from NT$3,000 to NT$6,000.[63] However, court decisions allow lane filtering for large heavy motorcycles when overtaking stopped vehicles.[64]

Legal status in the US

The legal confusion in the United States is exceptional. In a 2012 California survey, 53 percent of non-motorcycle drivers thought that lane splitting was legal.[65] At the time, there was no specific traffic law in California that addressed lane splitting. No legal prohibition of an action generally means that the action is lawful; however, there are other U.S. states in which there are no traffic laws explicitly prohibiting lane splitting,[33][36][40][66] but officials rely on other laws to regularly interpret lane splitting as unlawful.[40] For example, New Mexico does not address lane splitting by name, but has language requiring turn signals be used continuously for at least 100 ft (30 m) before changing lanes.[67] as well as other codes which may be cited by an officer.[68][69] Many other states have derived identical codes from the Uniform Vehicle Code.[70]

Lane splitting was legally defined for the first time in California by a bill signed into law in August 2016. The new law established a definition of lane splitting while making no mention of whether, or under what circumstances, it is allowed. It also permits the California Highway Patrol, in consultation with government and interest groups, to establish educational guidelines about lane splitting. This essentially gives the CHP permission to bring back the FAQ and advice on lane splitting which they published and rescinded in 2009 after one person complained.[71] Sport Rider magazine predicted that "issues are almost certain" due to the law's ambiguity as to what is and is not legal.[72] Cycle World said that while it, "is a step in the right direction, the AB 51 Bill doesn't actually do much to clear anything up."[73] Effective January 1, 2017, section 21658.1 was added to the California Vehicle Code and defines lane splitting, which is now explicitly legal in California.[74] The California Highway Patrol released new lane splitting safety tips on September 27, 2018.[75]

Bills to legalize lane splitting have been introduced in state legislatures around the United States over the last twenty years[when?], but none had been enacted before California's.[76][77][78][79][80][81][82]

Utah legalized filtering in 2019[83] and the law went into effect on May 14, 2019.[84] The Utah Department of Public Safety Highway Safety Office created infographics and videos that demonstrated safe and legal filtering.[85]

Montana's governor signed SB9, legalizing filtering in March 2021. The bill went into effect on October 1, 2021.[86] This law permits filtering at up to 20 mph (32 km/h) between vehicles that are stopped or moving at up to 10 mph (16 km/h).

Arizona's governor signed SB1273 on March 23, 2022,[87] and it will go into effect after 90 days after the end of the second regular session of the 55th Arizona State Legislature. This legislation mirrored Utah's bill, permitting motorcycles to travel at up to 15 mph (24 km/h) between completely stopped vehicles on roads with a speed limit of 45 mph (72 km/h) or slower and at least two adjacent lanes in the same direction of travel, as long as the movement could be made safely. Senator Tyler Pace sponsored the bill and Representative Frank Carroll co-sponsored it.[88] The bill received support from ABATE of Arizona, a state motorcyclists' rights organization.[89]

See also

Notes

- ^ NHSTA Glossary 2002.

- ^ a b c d NHSTA Motorcycle Factors 2002.

- ^ a b Hough 2000, p. 253.

- ^ a b c MAIDS (Motorcycle Accidents In Depth Study) Final Report 1.2 (PDF), ACEM, the European Association of Motorcycle Manufacturers, September 2004, p. 49, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-23, retrieved 2009-05-11

- ^ "Even in congested areas there is nearly always sufficient roadway width available for cyclists to lane share with stopped motorists, so cyclists filter forward through traffic jams." John Forester, Bicycle Transportation, second edition, p. 73

- ^ "In some states, it is legal for a motorcycle to ride between lanes of traffic. This is known as splitting lanes. Doing this when traffic is moving at normal speed is, of course, insane." Darwin Homstrom, The Complete Idiot's Guide to Motorcycles, p. 179

- ^ a b Sperley & Pietz 2010.

- ^ A European Agenda for Motorcycle Safety (PDF), Federation of European Motorcyclists Associations, April 2009, retrieved 2014-05-10

- ^ Tiwari 2007.

- ^ Cervero, Robert (2000), Informal transport in the developing world, UN-HABITAT, p. 90, ISBN 978-92-1-131453-3

- ^ Iles, Richard (2005), Public transport in developing countries, Emerald Group Publishing, p. 50, ISBN 978-0-08-044558-8

- ^ United Nations. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, United Nations (2005), Road Safety, United Nations Publications, p. 62, ISBN 978-92-1-120428-5

- ^ a b Vanderbilt 2008, p. 217.

- ^ Tiwari, Geetam (1999), "Towards A Sustainable Urban Transport System: Planning For Non-Motorized Vehicles in Cities" (PDF), Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific, no. 68, Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme Indian Institute of Technology, pp. 49–66

- ^ Downs 2004.

- ^ Forester, John (1993), Effective Cycling (6th f ed.), MIT Press, pp. 198, 313, 393, ISBN 978-0-262-56070-2

- ^ "Riding between rows of stopped or moving cars in the same lane can leave you vulnerable. A car could turn suddenly or change lanes, a door could open, or a hand could come out of a window." The California Motorcycle Handbook Archived 2014-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "It's often safer to take the whole lane, or at least ride a little bit to the left, rather than hug the right curb. Here's why: Cars at intersections ahead of you can see you better if you're squarely in the road rather than on the extreme edge where you're easily overlooked. ..." Michael Bluejay, bicyclesafe.com

- ^ a b c d e Squatriglia 2000.

- ^ "Motorcycle Statistics: Harry Hurt Interview". www.soundrider.com. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ^ "Is sharing lanes more or less dangerous than sitting in traffic?", WhyBike?, February 27, 2007, archived from the original on June 20, 2008, retrieved September 1, 2007

- ^ "FARS Encyclopedia".

- ^ Rice, Troszak & Erhardt 2015.

- ^ a b Clarke et al. 2004.

- ^ Lee, Tzu-Chang; Polak, John W.; Bell, Michael G.H.; Wigan, Marcus R. (2012). "The kinematic features of motorcycles in congested urban networks". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 49: 203–211. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2011.04.002. PMID 23036397.

- ^ Tzu-Chang, L., et al. (2010). "The Passenger Car Unit values of motorcycles at the beginning of a green period and in a saturation flow." 12th World Conference on Transport Research (WCTR), Lisbon, Portugal.

- ^ Tzu-Chang, L., et al. (2010). "The PCU Values of Motorcycles in congested flow." Transportation Research Board 89th Annual General Meeting, Washington, D.C., TRB

- ^ a b Software, Westsite nv: Web development en Internet. "Pendelen per motorfiets - Transport & Mobility Leuven". www.tmleuven.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ Hough 2000, p. 213.

- ^ a b Kim 2006.

- ^ Safety, New York Motorcycle & Scooter Task Force, retrieved October 17, 2013

- ^ Grava 2003, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b Grava 2003, p. 118.

- ^ a b Hough 2000, p. 212.

- ^ Parks 2003.

- ^ a b Preston 2004, p. 95.

- ^ Holmstrom 2001, p. 179.

- ^ a b Phillips 2007.

- ^ Vanderbilt 2009.

- ^ a b c Matthews 2015, pp. 41–42.

- ^ "California Motorcyclist Safety". www.chp.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-10-19. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- ^ "Lane splitting general guidelines". dmv.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-12-06. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-02. Retrieved 2022-07-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Oxford Systematics (July 2000), Motorcycle Transport – Powered Two Wheelers in Victoria (PDF), VicRoads & Victorian Motorcycle Advisory Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-18, retrieved 2007-04-07

- ^ Coyne, Mayblin & Mares 1996.

- ^ Balish 2006.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions of the Highway Patrol, 2009 State of California, 2009, archived from the original on 2009-04-11

- ^ Australian Road Rules General Amendments and Regulatory Impact Statement 2005, NTC National Transport Commission Australia, November 2005, archived from the original on 2009-08-03, retrieved 2009-05-11

- ^ Australian Road Rules Amendment Package 2005 Draft Regulatory Impact Statement (PDF), NTC National Transport Commission Australia, November 2005, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-29, retrieved 2009-05-11

- ^ "Bikers angry over lane-splitting ban plan". The Age. Melbourne. January 11, 2006.

- ^ Road Rules ~ Lane Splitting, Biker Aware, 2006, archived from the original on January 18, 2013, retrieved March 8, 2009

- ^ Lane Filtering, RMS, 2015-07-13

- ^ "Changes to road rules for motorcycle riders", Department of Transport and Main Roads, 1 February 2015

- ^ "Driving in Slovakia". Wheels on, travel. 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Motorradfahren im Stau und in der Rettungsgasse: Durchschlängeln erlaubt?)" [Riding a motorcycle in a traffic jam and in the emergency lane: is lane splitting allowed?]. ADAC. 2023-07-20. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Tober, Agnieszka (2022-07-23). "To irytujące, ale motocykliści mogą legalnie omijać korki" [It's annoying, but motorcyclists can legally bypass traffic jams]. Bezprawnik. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Pochłód, Krzysztof (2022-10-18). "Tak, motocykliści mogą się przeciskać między autami. Ale nie zawsze" [Yes, motorcyclists can squeeze between cars. But not always]. Interia. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Administrative Order No. 15 (May 15, 2008), Rules and Regulations For the Use and Operation of Motorcycles on Highways (PDF)

- ^ "Bill seeking to penalize lane-splitting riders up to P5,000 refiled in Congress". Top Gear Philippines. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "為什麼一堆機車愛鑽縫? 網掀二輪、四輪大戰". 地球黃金線 (in Chinese). 19 August 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

根據台北市交通大隊執法組組長林永川表示,有關機車鑽車縫並沒有相關罰責,不過如果在鑽車縫的過程中,如果有占用到禁行機車車道將會依《道路交通管理處罰條例》第45條第13項,處新台幣600元以上1,800元以下罰鍰。

- ^ "機車搶快鑽車縫不違法? 警:無明確罰則". TVBS (in Chinese). Retrieved 2023-01-09.

雖然機車穿梭沒有明確的罰則,但是在行進間,如果佔用到了禁行機車的車道,就已經違反了交通法規。

- ^ Article 2, Road Traffic Security Rules (道路交通安全規則第 2 條)

- ^ a b Article 92, Road Traffic Management and Penalty Act (道路交通管理處罰條例第 92 條)

- ^ "車流靜止時 法官:大型重機可鑽到車流前". The Liberty Times (in Chinese). Retrieved 2023-01-09.

法官認為,車流是在停止、靜止狀態,不能算是「同一車道違規超車」,所以警察以「違規超車」開罰是錯誤,判決撤銷裁罰。另台北高等行政法104年度院交上字第68號,上個月宣判也是做此見解。

- ^ The Safety Transportation Research and Education Center - University of California, Berkeley (May 3, 2012). "Press Release" (PDF). 2012 Motorcycle 'Lane Splitting' Intercept Survey. California Office of Traffic Safety. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

The OTS survey showed that only 53 percent of vehicle drivers thought that lane splitting is legal in California.

- ^ American Motorcyclist State Motorcycle Laws. Archived from the original Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine on March 16, 2011.

- ^ 66-7-325. Turning movements and required signals., Justia.com US Laws

- ^ Hough 2000, p. 214–215.

- ^ Besides violating 66-7-325 Turning Movements and required signals prohibit Lane Splitting, a motorcyclist lane splitting in New Mexico could be cited for 66-7-317 "Driving on roadways laned for traffic" [1] and 66-7-322 "Required position and method of turning at intersections" [2]

- ^ "Search Results for All US State Codes". Archived from the original on 2009-08-04. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ^ "Lane splitting". California Highway Patrol. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

A petitioner complained to the California Office of Administrative Law (OAL) that there was no formal rulemaking process for the guidelines, and raised other objections. The CHP discussed the issue with OAL and chose not to issue, use, or enforce the guidelines and thus, removed them from the website.

- ^ "The California Lane-Splitting Bill, AB 51, Has Passed the Senate", Sport Rider, August 4, 2016, retrieved October 21, 2016

- ^ MacDonald, Sean (August 4, 2016), "California's Lane-Splitting Bill Passes State Senate Vote; AB 51 is one step closer to becoming law", Cycle World, retrieved October 21, 2016

- ^ "Let motorcycles drive between lanes, and give them room, California Highway Patrol says". Los Angeles Times. 27 September 2018.

- ^ "California Motorcyclist Safety".

- ^ "California takes first step to establishing lane-splitting guidelines for motorcyclists". Los Angeles Times. September 2016.

- ^ Washington HB3159, 2004, archived from the original on 2009-08-03

- ^ Vogel 2005.

- ^ New Jersey Assembly Bill 1684 (Establishes task force to study lane splitting), 2008

- ^ Lane Splitting Proposed in Colorado, Biker News Online, 2007

- ^ Colorado Man Proposes New Traffic Legislation, NBC 11 News, September 25, 2007

- ^ Texas SB506, 2009

- ^ Hughes, Justin. "Utah Joins Civilized World, Legalizes Lane Splitting". RideApart.com. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ "Utah's New Lane Filtering Law". Utah Department of Public Safety. Retrieved 2019-03-29.

- ^ "Lane Filtering". Ride to Live Utah. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ ""Lane filtering" by motorcyclists in Montana is legal as of October 1". KPAX. 2021-09-26. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ^ "Chaptered Version of SB1273". apps.azleg.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ^ "SB1273 - 552R - I Ver". www.azleg.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ^ "ABATE of Arizona - Legislative Update". www.abateofaz.org. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

References

- Balish, Chris (2006), How to live well without owning a car, Ten Speed Press, p. 108, ISBN 978-1-58008-757-5

- Clarke, DD; Ward, P; Bartle, C; Truman, W (2004). "Motorcycle accidents: preliminary results of an in-depth case-study – Road Safety Research Report No. 54" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Coyne, Philip; Mayblin, Bill; Mares, Penny (1996), Motorcycle Roadcraft – The police rider's handbook to better motorcycling (11th impression ed.), The Stationery Office, pp. 139–140, ISBN 978-0-11-341143-6

- Downs, Anthony (2004), Still stuck in traffic: coping with peak-hour traffic congestion, Brookings Institution Press, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-8157-1929-8

- Grava, Sigurd (2003), Urban Transportation Systems: Choices for Communities, McGraw-Hill Professional, pp. 123–124, ISBN 978-0-07-138417-9

- Hahn, Pat (2012), Motorcyclist's Legal Handbook: How to Handle Legal Situations from the Mundane to the Insane, MotorBooks International, pp. 75, 134–135, ISBN 978-0-7603-4023-3

- Holmstrom, Darwin (2001), The Complete Idiot's Guide to Motorcycles, Alpha Books, ISBN 978-0-02-864258-1

- Hough, David L. (2000), Proficient Motorcycling: The Ultimate Guide to Riding Well (2nd ed.), U.S.: BowTie Press, p. 253, ISBN 978-1-889540-53-5

- Kim, Ray (February 22, 2006), Lane Splitting: Time Saver or Insanity?, archived from the original on September 7, 2008, retrieved April 4, 2009 Alt URL

- Matthews, J.L. (2015), How to Win Your Personal Injury Claim (9th ed.), Nolo, p. 41, ISBN 9781413321500

- Parks, Lee (2003), Total control: high performance street riding techniques, MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company, p. 45, ISBN 978-0-7603-1403-6

- Phillips, Kelli (January 19, 2007), "Bikers and auto drivers split on lane sharing: BAY AREA: Trend of riding between autos scares some, but motorcyclists say it's safe if everyone pays attention.", Contra Costa Times, Walnut Creek, CA

- Preston, Dave (2004), Motorcycle 101, Mixed MEDIA, ISBN 978-0-9747420-0-7

- Rice, Thomas; Troszak, Lara; Erhardt, Taryn (May 29, 2015). "Motorcycle Lane-splitting and Safety in California" (PDF). Safe Transportation Research & Education Center University of California Berkeley. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- Roderick, Tom (October 24, 2014), Preliminary Lane-Splitting Safety Report Released, Motorcycle.com

- Sperley, Myra; Pietz, Amanda Joy (June 2010), Motorcycle Lane-Sharing Literature Review (PDF), Oregon Department of Transportation, retrieved 2010-09-18

- Squatriglia, Chuck (October 30, 2000), "It's OK for Motorcycles To Squeeze Past Traffic", San Francisco Chronicle

- Tiwari, Geetam (2007), Urban Transport in India, Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations of India, archived from the original on 2009-05-22, retrieved 2009-06-01

- Vanderbilt, Tom (2008), Traffic: why we drive the way we do (and what it says about us), Random House, Inc., ISBN 978-0-307-26478-7

- Vanderbilt, Tom (February 25, 2009), "Lane Splitting", How We Drive, archived from the original on April 26, 2009, retrieved April 4, 2009 Alt URL

- Vogel, Kenneth P. (March 1, 2005), "Bill could give bikers free pass through traffic.", The News Tribune, Tacoma, Washington

- Yang, Sarah (May 29, 2015). "Is motorcycle lane-splitting safe? New report says it can be". Berkley News. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- "Glossary", National Agenda for Motorcycle Safety, US Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration/Motorcycle Safety Foundation, c. 2002, retrieved September 18, 2010

- Motorcycle Factors: Lane Use, US Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration/Motorcycle Safety Foundation, c. 2002, retrieved October 8, 2013

Further reading

All available from the United Kingdom Department of Transport websites (executive summary), and the Transportation Research Board Record publication:

- WSP Policy and Research UK, Motorcycles and congestion: the effect of modal shift: Phase 3 policy testing. 2004, WSP for Uk Department for Transport: Cambridge UK. p. 44.

- WSP Policy and Research UK, Motorcycles and congestion: the effect of modal shift: Phase 2 – Modelling Methodology. 2004, WSP for Uk Department for Transport: Cambridge UK. p. 47.

- WSP Policy and Research UK, et al., Motorcycles and congestion: the effect of modal shift: Summary Final Report. 2004, WSP for Uk Department for Transport: Cambridge UK. p. 26.

- Burge, P., et al., The modelling of motorcycle ownership and usage: a UK study. Transportation Research Record J Transportation Research Board, 2007(2031): p. 59-68.