Land reclamation in Singapore

The reclamation of land from surrounding waters is used in Singapore to expand the city-state's limited area of usable, natural land. Land reclamation is most simply done by adding material such as rocks, soil and cement to an area of water; alternatively, submerged wetlands or similar biomes can be drained.

In Singapore, the former has been the most common method until recently, with sand the predominant material used. Due to a global shortage and restricted supply of the required type of sand (river and beach sand, not desert sand), Singapore has switched to polders for reclamation since 2016 — a method from the Netherlands in which an area is surrounded by a dyke and pumped dry to reclaim the land.

Land reclamation allows for increased development and urbanization,[1] and in addition to Singapore has been similarly useful to Hong Kong and Macau. Each of these is a small coastal territory restrained by its geographical boundaries, and thus traditionally limited by the ocean's reach. The use of land reclamation allows these territories to expand outwards by recovering land from the sea. At just 719 km2 (278 sq mi), the entire country of Singapore is smaller than New York City. As such, the Singaporean government has used land reclamation to supplement Singapore's available commercial, residential, industrial, and governmental properties (military and official buildings). Land reclamation in Singapore also allows for the preservation of local historic and cultural communities, as building pressures are reduced by the addition of reclaimed land.[2] Land reclamation has been used in Singapore since the early 19th century, extensively so in this last half-century in response to the city-state's rapid economic growth.[3] In 1960, Singapore was home to fewer than two million people; that number had more than doubled by 2008, to almost four and a half million people.[4] To keep up with such an increase in population (as well as a concurrent surge in the country's economy and industrialization efforts), Singapore has increased its land mass by 22% since independence in 1965, with land continuously being set aside for future use.[5][6] Though Singapore's native population is no longer increasing as rapidly as it was in the mid-twentieth century, the city-state has experienced a continued influx in its foreign population,[7] resulting in a continued investment in land reclamation by the government. The government thus plans to expand the city-state by an additional 7-8% by 2030.[5]

History

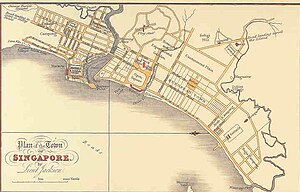

The early phases of land reclamation began not long after Sir Stamford Raffles arrived in what would become modern Singapore in 1819. Raffles had come to the area with the goal of developing a British port to rival that of the Dutch, and though contemporary Singapore was the ideal location for a harbour, it was at the time only a small fishing village.[8][3] Converting this village into a significant trading centre required reorganization and better utilization of the land. After some alterations to his original plans, Raffles decided in 1822 that the commercial centre of his new port should be located on the south bank of the Singapore River, close to the river's mouth.[9] At that time, the south bank was largely uninhabited swamp, covered in mangrove trees and sprinkled with creeks.[9] Though Singapore's first British Resident, William Farquhar, expressed concerns about the cost and feasibility of reclaiming this land, it was eventually decided that the project was achievable.[9] The southwest bank of the river was found to be prone to flooding, so Raffles decided to dismantle a small hill (located in today's Raffles Place) and use the soil to raise and fill in the low-lying areas that would otherwise be affected by flooding.[9] The project began in the second half of 1822, and was completed in three to four months (largely by Chinese, Malay, and Indian labourers).[9] The land was broken up into lots, which were sold off to commercial investors.[9]

After this first land reclamation project, there were no significant alterations to Singapore's geography until 1849, which brought the building of port facilities that became increasingly important after the establishment of the British Straits Settlements in 1826 and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, both of which allowed for improved connections between the city-state and Europe.[3]

After the turn of the century (particularly from 1919 to 1923), Singaporean land reclamation was primarily the result of a need for increased public utilities (such as roads and railways) and military coastal protection.[3] Such development was interrupted by World War II, when the Japanese occupied Singapore and directed focus away from an improved Singapore and towards an extended Japanese culture. There was thus a lull in industrialization in Singapore during this period, which continued throughout the 1950s and early 1960s (during which time Singapore experienced extensive political change) until the city-state's participation in the founding of Malaysia in 1963.[3] As part of Malaysia and continuing after independence in 1965, Singapore benefitted from economic development programs, which both enabled and required significant land reclamation projects.[3] Rapidly increasing demand for industrial, infrastructural, commercial, and residential land resulted in projects that reclaimed hundreds of hectares (acres) at a time.[3] The Jurong Industrial Estate began development in the early 1960s to meet industrial land needs, and by 1968 already housed 153 factories, with another 46 under construction. The original landscape of the region was greatly changed and is now restricted to the areas around the Pandan Reservoir and Sungei Pandan. Also in the early 1960s, Singapore's central business district was extended into land reclaimed from the sea.[3] Post-war industrialization and land reclamation transformed Singapore's weak economy.

In 1981, Singapore Changi Airport opened after the clearing of roughly 2 km2 (0.8 sq mi) of swampland and the introduction of over 52,000,000 m3 (68,000,000 cu yd) of land- and seafill. As Changi Airport maintains a policy of continual development in preparation for the future, a third airport terminal was planned from the beginning, and was opened on January 1, 2007.

By 1991, 10% of Singapore was reclaimed land.[3] By that year, industrial land on Singapore's mainland had again grown scarce, and it was decided that seven islets south of Jurong would be merged to form one large island, Jurong Island. By 2008, Singapore was one of the top three oil trading and refining hubs globally.[10] The necessary facilities for such an involvement in the oil industry require a very large amount of space, and today, Singapore's facilities are housed almost entirely on Jurong Island and the Jurong Industrial Estates.[10]

In 1992, the Marina Centre and Marina South land reclamation projects were completed after their commission in the late 1970s, encompassing 360 ha (890 acres) of waterfront development. These projects involved the removal of the Telok Ayer Basin and Inner Roads; the mouth of the Singapore River was also rerouted to flow into Marina Bay rather than directly into the sea. The Marina Bay reclamation projects added significant waterside land adjacent to Singapore's central business district, creating prime real estate that is used for commercial, residential, hotel, and entertainment purposes today.

Singapore continues to develop and expand, with plans to expand the city's land area by an additional 7-8% of reclaimed land by 2030.[11]

Recent difficulties with sand mining

Reclamation of submerged land requires a substance to fill in the reclaimed area. Given the shallow depth of the waters surrounding much of Singapore, sand has generally been seen as the best option for this process.[12] Raffles used soil from a razed hill to raise the southwest bank of the Singapore River, but sand is the predominant choice.[13] In fact, Singapore has used so much sand that it has run out of its own, and imports sand from surrounding areas in order to meet its land reclamation needs.[5] Though industries around the world depend on sand, the United Nations Environment Programme found Singapore to be the largest importer of sand worldwide in 2014.[5] In 2010 alone, Singapore imported 14.6 million tons of sand.[13]

In recent years, however, sources of sand have become more scarce. In 1997, Malaysia announced a ban on the export of sand,[13] yet Malaysian media continue to report rampant smuggling of sand into Singapore, leading then former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad to protest that these corrupt sand miners were "digging Malaysia and giving her to other people".[13]

In 2007, Indonesia enacted a ban against exporting sand specifically to Singapore.[13] This ban followed tensions between Singapore and Indonesia regarding islands lying between the two countries: sand miners had reportedly all but demolished these islands.[13] In 2007, more than 90% of Singapore's imported sand had come from Indonesia.[14] The ban resulted in an increase in construction costs in Singapore as well as the need to find new sources of sand, which has become increasingly difficult as more neighbouring countries institute their own bans and regulations regarding the export of sand.[14] In 2009, Vietnam instituted its own ban against the export of sand to Singapore,[15] followed the same year by Cambodia, although that country's prohibition was less all-encompassing: though sand from some seabeds could still be exported, river sand could no longer be dredged and distributed.[13] More recently, however, certain rivers that receive replenishments of sand naturally due to their proximity to seawater have been made exempt from this ban.[13] In spite of these restrictions, Cambodia, which provided just 25% of Singapore's sand imports in 2010, is now its primary source of sand. This increase has dramatically changed local ecosystems.[13] After the dredging of Cambodia's Tatai River (exempt from the ban) began in 2010, locals saw an estimated 85% reduction in the catch of fish, crab, and lobsters; tourist numbers have similarly decreased as construction and noise have surged.[13] People living near the river have petitioned for an end to sand mining there.[13] Large-scale damage has been seen throughout Koh Kong Province as a result of this dredging.[15]

The Singaporean government refuses to disclose where the sand it receives is imported from.[15] The Ministry of National Development has said that the government buys sand from "a diverse range of approved sources", but maintains that further details are not public information.[15]

Starting in November 2016, Singapore has started to use a different land reclamation method, the polder development method, which should lessen its reliance on sand for land reclamation.[14] Used by the Netherlands for many years, this method involves building a wall to keep out seawater from a low-lying tract of land, known as a polder, while drains and/or pumps control water levels.[14] It is to be used first on the northwestern tip of Pulau Tekong, a future military training base which will be expanded by 810 ha (2,000 acres).[14]

Controversy with Malaysia

In 2003, Singapore received complaints from Malaysia over land reclamation projects at either end of the Straits of Johor, which separate the two countries.[5] Malaysia claimed that Singapore's plans infringed on Malaysian dominion and were detrimental to both the environment and the livelihoods of local fishermen,[5] and legally challenged Singapore under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.[5] The dispute was settled after arbitration.[5]

More recently, Singapore has issued its own complaints against Malaysia regarding the latter's two land reclamation projects in the Straits of Johore. One project would involve the creation and linkage of four islands within the strait, creating a new metropolis called Forest City,[5] which Malaysia plans to advertise as a garden oasis, with buildings covered by greenery and an impressive expanse of public transport. Progress on the project came to a halt after Singapore protested against its construction in 2014, but the Malaysian government reportedly approved a scaled-down version of the project in January 2015.[5]

Environmental consequences

Singapore's industrialisation (particularly in terms of coastal development) and land reclamation projects have resulted in the extensive loss of marine habitats along the city-state's shores.[16] The majority of Singapore's southern coast has been altered through the process of land reclamation, as have large areas of the northeastern coast.[16] Many offshore islands have been changed, often through the filling of waters between small islands in order to create cohesive landmasses.[16]

Such development has led to the loss of 95% of Singapore's mangroves.[17] When Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore in 1819, the land was largely mangrove swamp; today, mangrove cover accounts for less than 0.5% of Singapore's total land area.[18][19] This loss has greatly diminished the beneficial effects of mangroves, which include protection against erosion and reduction in organic pollution,[20] both of which serve to ameliorate coastal water quality.[20]

Singapore has also suffered an enormous loss in coral reefs as the result of extensive land and coastal development.[17] Prior to the land reclamation of the last several decades, Singapore's coral reefs covered an estimated 100 km2 (39 sq mi).[19] By 2002, that number had dropped to 54 km2 (21 sq mi).[19] Estimates are that up to 60% of the habitat is no longer sustainable.[19] Since coral reef monitoring was first instigated in the late 1980s, a clear overall decline in live coral cover has been noted, as has a decline in the depths at which corals thrive.[21] Fortunately, though there have been limited extinctions of local species, overall coral reef diversity has not diminished: the main loss has instead been a general, relatively equal decrease in the population abundance of each species.[21] Coral reefs are valued for their work towards carbon sequestration and shore protection (particularly in the dispersal of wave energy), as well as for their contributions to fisheries production, ecotourism, and scientific research.[22]

Singapore has also seen the negative effects of industrialisation impact several other coastal and marine habitats, such as seagrass, seabed, and seashores, all of which have suffered loss or degradation similar to that of the mangroves and coral reefs.[17]

Though much harm has been done to Singapore's aquatic ecosystems as the result of land reclamation projects and expansive industrialisation, there has been more of an effort in recent years to accommodate and restore damaged environments.[23] Since the mid-1990s, more attention has been paid to environmental impact assessments (EIAs), which identify the potential ecological consequences of a given developmental venture as well as possible ways to lessen the environmental harm.[17] In the development of the Semakau Landfill, for example, an extensive EIA was carried out after the project's commission in 1999.[24] The assessment found that coral reefs and mangroves within the allotted 350 ha (860 acres) project would be harmed,[25] and as a result plans were put in place to reforest the mangroves elsewhere, and sediment screens were installed to prevent silt from reaching reefs that would have otherwise been negatively affected.[25] EIAs are not, however, required by any legislature, and thus are not mandatory for land reclamation projects.[17] Yet the Singapore government has been increasingly open to public feedback regarding increased sustainability in future land projects.[23]

In terms of restoration efforts, nature activists and public authorities alike have been working more and more towards the strengthening of biotic communities.[23] Though Singapore has seen the extinction of more than 28% of native flora and fauna, it has also witnessed the introduction of foreign flora and fauna to its ecosystems, increasing the country's biodiversity. Efforts towards the development of nature reserves have also helped to protect local wildlife, over half of which is now present only in such reserves.

See also

- Environmental issues in Singapore

- Land reclamation in Hong Kong

- Future developments in Singapore

- Urban planning in Singapore

- Malaysia-Singapore border

- Indonesia-Singapore border

References

- ^ R. Glaser, P. Haberzettl, and R. P. D. Walsh, "Land Reclamation in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau," GeoJournal (August 1991), accessed February 16, 2017.

- ^ Tai-Chee Wong, Belinda Yuen, and Charles Goldblum, ed., Spatial Planning for a Sustainable Singapore (Springer Science + Business Media B.V., 2008), 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Glaser, "Land Reclamation".

- ^ Wong, Spatial Planning. VII.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Such Quantities of Sand," The Economist. February 26, 2015.

- ^ Wong, Spatial Planning. 120–21.

- ^ Wong, Spatial Planning. 23.

- ^ Matt K. Matsuda, Pacific Worlds: A History of Seas, Peoples, and Cultures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). 197.

- ^ a b c d e f National Library Board Singapore, http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/feddcf2a-2074-4ae6-b272-dc0db80e2146 “Singapore’s First Land Reclamation Project Begins", last modified 2014.

- ^ a b Wong, Spatial Planning. 51.

- ^ Goh Chok Tong, "Singapore is the Global City of Opportunity" (Keynote Address, Singapore Conference in London, March 15, 2015).

- ^ Asad-ul Iqbal Latif, Lim Kim San: A Builder of Singapore (ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2009).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Denis D. Gray, "Cambodia sells sand; environment ravaged", Asian Reporter (2011).

- ^ a b c d e Alice Chia, "New reclamation method aims to reduce Singapore's reliance on sand," Channel News Asia (2016).

- ^ a b c d Lindsay Murdoch, "Sand wars: Singapore's growth comes at the environmental expense of its neighbours", The Sydney Morning Herald (2016).

- ^ a b c Wong, Spatial Planning. 170.

- ^ a b c d e Wong, Spatial Planning. 171.

- ^ Matt K. Matsuda, Pacific Worlds: A History of Seas, Peoples, and Cultures. 197-200.

- ^ a b c d Wong, Spatial Planning. 172.

- ^ a b Wong, Spatial Planning. 176.

- ^ a b Wong, Spatial Planning. 173.

- ^ Wong, Spatial Planning. 174.

- ^ a b c Wong, Spatial Planning. 11.

- ^ Wong, Spatial Planning. 177-178.

- ^ a b Wong, Spatial Planning. 178.