Lampert Hont-Pázmány (lord)

Lampert Hont-Pázmány | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1060s |

| Died | July 1132 near the river Sajó |

| Noble family | gens Hont-Pázmány |

| Spouse(s) | 1, daughter of Béla I of Hungary 2, Sophia N |

| Issue | Bény II Nicholas Sixtus |

| Father | Krazeg (stepfather) |

Lampert from the kindred Hont-Pázmány (Hungarian: Hont-Pázmány nembeli Lampert; killed July 1132) was a Hungarian powerful lord at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, who was related to the ruling Árpád dynasty by his marriage. He was one of the richest aristocrats of the kingdom during that time. He founded a Benedictine abbey near Bozók (present-day Bzovík, Slovakia).

Family and landholdings

King Béla II of Hungary confirmed the former donations to the newly established Bozók Abbey in 1135, which preserved many details about the family relationships of Lampert, the founder of the monastery. Accordingly, Lampert (II) was born into the influential and extensive gens (clan) Hont-Pázmány in the 1050s or 1060s. Their ancestors, German knights Hont and Pázmány arrived in the late 10th century to the Kingdom of Hungary and they actively participated in the defeat of the rebellious chieftain Koppány. It is plausible that Hont, who settled down in Upper Hungary, was the great-grandfather of Lampert.[1] According to the 1135 document, his namesake grandfather, Lampert (I) – Hont's son – lived during the reign of Stephen I of Hungary,[2] and was granted the villages Egyházasmarót (Hontianske Moravce) and Palatnya in Hont County from King Stephen around 1030. Lampert (I) also had a brother Bény (I).[1][3] The father of Lampert (II) is unidentified. Lampert had a brother Hippolytus (Ipoly). It is plausible that their father died early, as Lampert (and possibly Hippolytus) was adopted by a certain noble, the childless Krazeg.[4]

Lampert inherited large-scale domains in Upper Hungary. By the end of his life, he possessed approximately 30 landholdings, becoming one of the richest aristocrats of the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries.[5] The majority of his lands laid north of the section of the river Ipoly (Ipeľ) between the settlements Visk (present-day Vyškovce nad Ipľom, Slovakia) and Balassagyarmat along the line of gyepű, where the Hont-Pázmánys settled a century earlier.[6] The royal charter of 1135 lists the estates Lampert had donated to the Bozók Abbey. The majority of his landholdings are located in present-day Slovakia, but he also owned several settlements that are now unidentifiable (these are marked with quotation marks and italics). The document also contains the circumstances of the acquisition of the listed landholdings; where this does not appear, it is a clearly inherited estate from the Hont-Pázmány wealth. Among others, Lampert inherited Bozók, Csenke (Čenkovce), Bény (Bíňa), Páld (Pavlová), Egyházasmarót, Palatnya, meadows and groves in Kürt (Ohrady), three acres of land in "Ocyva", ten acres of land in Szebele, one acres of land in "Dopub" and arable lands in Nyék (Vinica). Lampert and his family also owned each portions in Kelenye (Kleňany).[3]

According to the 1135 charter, Lampert acquired several landholdings in different ways. He bought Badin (present-day Dolný Badín and Horný Badín) from a certain Iremyr. He was granted the estate "Kukezu" (possibly it is identical with present-day Kosihovce or Kamenné Kosihy) from his stepfather Krazeg. Sometime before 1108, Duke Álmos donated the village of Nénye (Nenince) to Lampert, after its original owner, a certain Prodsa died without descendants. Lampert bought "Zeorna" along the stream Olvár (today in Šahy) from a certain noble Porodom. As part of the dowry via his first marriage (see below), Lampert was granted the estates Ipolypásztó, Bori and two vineyards in Szigetfő (present-day Pastovce, Bory and Rácalmás, respectively) by King Ladislaus I of Hungary in the 1080s. Lampert bought "Voücta" (Visztoka?) from a certain Dragony. He acquired Megyer along the river Danube from a certain David. He also bought "Chemer" from a certain Gregory.[3]

Marriages

The aforementioned royal charter of 1135 narrates that Lampert Hont-Pázmány married to an unidentified daughter of the late Béla I of Hungary upon the courtesy of the princess' brother Ladislaus I.[7] The document refers to the lady as Ladislaus' "soror" ("sister"), without her name.[8] The wedding took place most plausibly in the 1080s, and this unidentified princess was probably the youngest child of Béla I, who could have been born a year or two before her father's death (1063) and reached adulthood by the time of her brother's reign (1077–1095).[9] Lampert was granted respectable dowry from his brother-in-law, King Ladislaus: the villages Ipolypásztó (with its royal manor) and Bori in Upper Hungary and two vineyards in Szigetfő (present-day a borough of Rácalmás) in Central Hungary. With this marriage, Lampert became one of the few aristocrats, who was related to the ruling Árpád dynasty, which reflected his wealth, loyalty and high social prestige.[10] Historian Péter Báling also considered that Lampert presumably supported the aspirations of Béla's sons, Géza I then Ladislaus I against their cousin Solomon for the acquisition of the Hungarian throne, and this assistance enabled him to marry into the royal family.[11] Plausibly, the marriage remained childless and the unidentified princess died by that time, when Lampert founded the monastery of Bozók.[7]

Béla II's same charter also mentions a certain Sophia as Lampert's wife in another text place. Accordingly, Lampert, his wife Sophia and their son Nicholas had established the abbey with their donations. Former historiography incorrectly considered this Sophia is identical with Béla I's namesake daughter, who was the spouse of Ulric I, Margrave of Carniola, then Magnus, Duke of Saxony.[12][13] However, historian Mór Wertner proved that Lampert's first wife from the Árpád dynasty and the aforementioned Sophia are different persons. The 1135 diploma does not refer to Sophia as a royal relative and does not mention any referrals (the lack of inclusion of word "prefata"), which would result in identification between the two ladies and implies that Sophia from an unidentified noble family was the second wife of the powerful lord (on the other hand, it is also rare for a monarch to have two children of the same name if the elder has lived into adulthood).[9][14] Lampert had three sons: Bény (II) – who predeceased him –, Nicholas and Sixtus (or Syx).[15] Béla II nor does refer to them as his relatives when he mentions them, consequently all of them were born from their father's second marriage. However, the lack of mention of kinship may also be due to Lampert and his family supporting Boris' claim to the throne against Béla II (see below), so it may be that some or all of them were descendants of Béla I.[9][14] Majority of scholars accepted Wertner's interpretation.[3][5][7][14] In contrast, genealogist Szabolcs de Vajay claimed that Sophia is identical with the unidentified princess, and, in fact, she was the daughter of Géza I (then only a prince) and his first wife Sophia of Looz (Loon). The orphan princess was guarded by his uncle Ladislaus I, according to Vajay. This theory also modified Lampert's age, extending his birth by at least ten years. Vajay argued Lampert's landholdings belonged to the territory of Prince Géza's ducal realm in Nitra (Nyitra).[16]

Activity

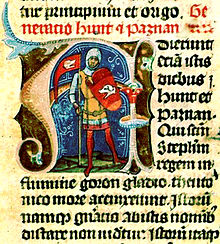

[...] Having secured the aid of the Ruthenians and the Poles, Boris came to the borders of Hungary to the place called Sajó. The king [Béla II] collected an army and went forth to meet him. Many of the nobles went over to Boris's party. Then the great men of Hungary were called into council with the king. [...] The king and his counselors, as far as was in their power, separated the sheep from the goats, and firmly resolved to kill the traitors on the spot, lest they should go over to Boris if there were delay, and the safety of the kingdom should be thus imperiled. Then tumult arose, and they took prisoner ispán Lampert; and as they dragged him away from the king, his brother [Hippolytus] cleft his head with a stool and the brain issued from the skull. They beheaded there his son, ispán Nicholas, and they put to death Mojnolt of the Ákos kindred, and others.

Only few sources have survived, which contain information about his political and social activity. By the end of the 11th century, Lampert belonged to the retinue of Coloman, King of Hungary, whose whole reign was overshadowed by series of sharp confrontation with his younger brother Álmos (however, as mentioned above, the prince once donated land to Lampert, when he still ruled the ducatus before 1108).[18] Lampert and his son Nicholas were also members of the royal court of Coloman's son, Stephen II of Hungary. They belonged to the companion of the king in July 1124, who visited Dalmatia to confirm his father's former grants and privileges to the coastal cities.[19] This data confirms that Lampert and his son had also participated in the royal campaign against the province, taking advantage of the temporary absence of the Venetian fleet from the Adriatic Sea.[15] According to Ferenc Makk, Lampert was an important member of that "pro-Coloman" baronial group, which began to slowly disintegrate by the end of the reign of Stephen II.[20]

Béla II's charter from 1135 narrates that Lampert, Sophia and Nicholas erected a Benedictine monastery in their estate Bozók during the reign of Stephen II and the episcopal tenure of Felician, Archbishop of Esztergom. Consequently, the foundation of the abbey occurred sometime between 1124 and 1131,[7] but most likely in the period from 1127 to 1131.[21] They donated approximately 20 landholdings to the newly founded monastery.[5] Sixtus – who was not involved in the foundation – retained his ownership over his portion in Kelenye. The document also narrates that Lampert's another son, Bény was deceased by the time of the foundation of the abbey. They offered some serfs to the Benedictine friars for his spiritual salvation.[14] The royal manor at Ipolypásztó was registered by Judge royal Julius to the accessories of the Bozók Abbey.[22] By 1181, the administration of the abbey was taken over by the Premonstratensians.[23]

The childless Stephen II died in March 1131. The late Álmos' blinded son Béla II ascended the throne after his predecessor's nephew, Saul whom Stephen II had nominated as his heir had died following a possible civil war. At "an assembly of the realm near Arad" in early to mid-1131, Queen Helena ordered the slaughter of all noblemen who were accused of having suggested the blinding of her husband to King Coloman. Lampert tacitly accepted the person of the new ruler, but his political influence greatly diminished. In the next year, Coloman's alleged son Boris tried to dethrone Béla II with the support of Bolesław III of Poland. After Boris arrived in Poland, a number of Hungarian noblemen joined him.[24] Others sent messengers to Boris to express their support, whether Lampert was among them is unknown. Accompanied by Polish and Rus' reinforcements, Boris broke into Hungary in mid-1132.[24] Before launching a counter-attack against Boris, Béla convoked a council on the river Sajó in July 1132.[24] Lampert and his kinship were also present during the meeting. The Illuminated Chronicle relates that the King asked "the great men of Hungary" who were present if they knew whether Boris "was a bastard or the son of King Coloman". The King's partisans attacked and slaughtered all those who proved to be "disloyal and contrary minded". Lampert was brutally murdered by his own brother Hippolytus, who beat him to death with a chair, while his son Nicholas was captured and beheaded. In the subsequent decisive battle, which was fought on the river Sajó on 22 July 1132, the Hungarian and Austrian troops defeated Boris and his allies.[24] According to historian Ferenc Makk, this event resulted the final disintegration of the "pro-Coloman" group, Hippolytus turned against his kinship and swore loyalty to Béla II.[20] Three years later, Béla II enlisted the late Lampert's donations to the monastery at Bozók. Makk considered the Benedictine friars initiated the royal confirmation of the donations, thus making themselves independent of the person of the founder who died as a "disloyal". This coincided with the political objective of the king who sought to consolidate his power.[25]

References

- ^ a b Karácsonyi 1901, p. 184.

- ^ Wertner 1892, p. 169.

- ^ a b c d Bakács 1971, p. 299.

- ^ Wertner 1892, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Makk 1994, p. 393.

- ^ Bakács 1971, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d Zsoldos 2020, p. 95.

- ^ Báling 2021, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Wertner 1892, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Zsoldos 2020, p. 132.

- ^ Báling 2021, p. 401.

- ^ Báling 2021, p. 470.

- ^ Wertner 1892, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d Báling 2021, pp. 397–398.

- ^ a b Karácsonyi 1901, p. 185.

- ^ Vajay 2006, pp. 33–34.

- ^ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 161), pp. 299–301.

- ^ Makk 1989, p. 133.

- ^ Makk 1972, p. 43.

- ^ a b Makk 1972, p. 44.

- ^ Bakács 1971, p. 31.

- ^ Szőcs 2017, p. 1072.

- ^ Bakács 1971, p. 244.

- ^ a b c d Makk 1989, p. 32.

- ^ Makk 1972, pp. 47–48.

Sources

Primary sources

- Bak, János M.; Veszprémy, László; Kersken, Norbert (2018). Chronica de gestis Hungarorum e codice picto saec. XIV [The Illuminated Chronicle: Chronicle of the deeds of the Hungarians from the fourteenth-century illuminated codex]. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-6338-6264-3.

Secondary studies

- Bakács, István (1971). Hont vármegye Mohács előtt [Hont County Before the Battle of Mohács] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Báling, Péter (2021). Az Árpád-ház hatalmi kapcsolatrendszerei. Rokonok, barátok és dinasztikus konfliktust Kelet-Közép-Európában a 11. században és a 12. század elején [The Power Relations of the Árpád Dynasty. Relatives, Friends and Dynastic Conflict in East-Central Europe in the 11th Century and Early 12th Century] (in Hungarian). Arpadiana VII., Research Centre for the Humanities. ISBN 978-963-416-246-9.

- Karácsonyi, János (1901). A magyar nemzetségek a XIV. század közepéig. II. kötet [The Hungarian genera until the middle of the 14th century, Vol. 2] (in Hungarian). Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- Makk, Ferenc (1972). "Megjegyzések II. Béla történetéhez [Remarks to the History of Béla II]". Acta Universitatis Szegediensis: Acta Historica (in Hungarian). 40: 31–49. ISSN 0324-6965.

- Makk, Ferenc (1989). The Árpáds and the Comneni: Political Relations between Hungary and Byzantium in the 12th century (Translated by György Novák). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-5268-X.

- Makk, Ferenc (1994). "Lampert 2.". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 393. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Szőcs, Tibor (2017). "Miből lett az országbíró? Az udvarispáni tisztségek kialakulása [What was the Origin of the Judge Royal? On the Emergence of the Office of Court Ispán]". Századok (in Hungarian). 151 (5). Magyar Történelmi Társulat: 1063–1088. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Vajay, Szabolcs (2006). "I. Géza király családfája [The Family Tree of King Géza I]". Turul (in Hungarian). 79 (1–2). Magyar Heraldikai és Genealógiai Társaság: 32–39. ISSN 1216-7258.

- Wertner, Mór (1892). Az Árpádok családi története [Family History of the Árpáds] (in Hungarian). Szabó Ferencz N.-eleméri plébános & Pleitz Fer. Pál Könyvnyomdája.

- Zsoldos, Attila (2020). The Árpáds and Their People. An Introduction to the History of Hungary from cca. 900 to 1301. Arpadiana IV., Research Centre for the Humanities. ISBN 978-963-416-226-1.