Oneida Lake

| Oneida Lake | |

|---|---|

| Tsioqui (Oneida) | |

View of Frenchman Island and Dunham Island from Cicero, a suburban Syracuse town | |

| Location | Oneida / Oswego counties, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°12′0″N 75°54′0″W / 43.20000°N 75.90000°W |

| Primary inflows | Oneida Creek, Fish Creek, Chittenango Creek |

| Primary outflows | Oneida River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 21 mi (34 km) |

| Max. width | 5 mi (8.0 km) |

| Surface area | 50,894 acres (79.5 sq mi; 206.0 km2) |

| Average depth | 22 ft (6.7 m) |

| Max. depth | 55 ft (17 m) |

| Water volume | .331 cu mi (1.38 km3) |

| Surface elevation | 369 ft (112 m) |

| Islands | Big Isle, Dunham's Island, Frenchman Island, Little Island, Long Island, Wantry Island |

| Settlements | (see article) |

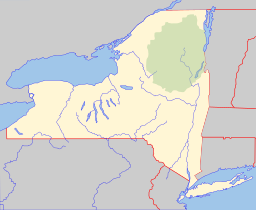

Oneida Lake is the largest lake entirely within New York state, with a surface area of 79.8 square miles (207 km2).[1][2] The lake is located northeast of Syracuse and near the Great Lakes. It feeds the Oneida River, a tributary of the Oswego River, which flows into Lake Ontario. From the earliest times until the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, the lake was part of an important waterway connecting the Atlantic seaboard of North America to the continental interior.

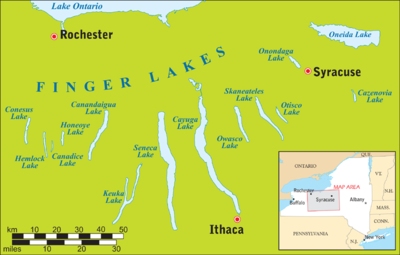

The lake is about 21 miles (34 km) long and about 5 miles (8.0 km) wide with an average depth of 22 feet (6.7 m). The shoreline is about 55 miles (89 km). Portions of six counties and 69 communities are in the watershed. Oneida Creek, which flows past the cities of Oneida and Sherrill, empties into the southeast part of the lake, at South Bay. While not geologically considered one of the Finger Lakes, Oneida Lake, because of its proximity, is referred by some as their "thumb". Because it is shallow, it is warmer than the deeper Finger Lakes in summer and its surface freezes solidly in winter. It is popular for the winter sports of ice fishing and snowmobiling.

Name

The lake is named for the Oneida, the Iroquoian Native American tribe that historically occupied a large region around the lake, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois. The name Oneida comes from the word Oneyoteaka, their endonym which translates to "People of the Standing Stone".[3] The Oneida called the lake Tsioqui in their language, meaning "White Water".[4]

History of navigation

During the 18th and early 19th centuries Oneida Lake and its tributary Wood Creek were part of the Albany-Oswego waterway from the Atlantic seaboard westward via the Hudson River and through the Appalachian Mountains via the Mohawk River; travel westward then was by portage over the Oneida Carry to the Wood Creek-Oneida Lake system. The navigable waterway exited Oneida Lake by the Oneida River, which led to the Oswego River and Lake Ontario, from where travelers could reach the other Great Lakes.

Following the American Revolutionary War, the United States forced the Iroquois nations to cede most of their lands in that region, as most of them had allied with the British, who were defeated. In addition, demand from settlers created pressure for such cessions. White settlers improved the natural waterway by constructing a canal with locks within Wood Creek to Oneida Lake. This system was significantly improved—from 1792 to 1803—by cutting a canal across the Oneida Carry, after which commercial shipping across Oneida Lake increased substantially. [5] Even more significant was the completion in 1825 of the Erie Canal, which bypassed the Oneida Lake system and enhanced travel through the entire Mohawk Valley. This caused the population around the lake to lose their navigable waterway eastward.

In 1835 Oneida Lake was connected to the Erie Canal system by construction of the (old) Oneida Canal, which ran about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) from Higginsville on the Erie Canal northward to Wood Creek, about 2 miles (3.2 km) upstream of Oneida Lake. Built poorly with wooden locks, the Oneida Canal was closed in 1863.[6]

When the Erie Canal was redesigned and reconstructed to form the New York State Barge Canal in the early 20th century, the engineers made use of natural rivers and lakes where possible. The new barges were powered internally (by diesel or steam engines), so they could travel open water and against a current; the system no longer needed infrastructure for drawing vessels externally — i.e., drawpaths and draft animals. After it straightened Fish Creek on the east, the new canalway entered Oneida Lake at Sylvan Beach and exited west with the Oneida River at Brewerton. New terminal walls at Sylvan Beach, Cleveland, and Brewerton allowed barges to load and unload cargo and to stay overnight. A new break wall was installed, preventing lake waves from entering the canal and protecting against shoaling.[citation needed] These improvements provided towns along the shoreline of Oneida Lake with access again to navigable waterways east and west.

Geology

Oneida Lake is a remnant of Glacial Lake Iroquois, a large prehistoric lake formed when glaciers blocked (from downstream) the flow of the St. Lawrence River, the outlet of the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean.

Adjacent places

Counties

Towns and villages

- Brewerton—Southwest

- Bridgeport—Southwest

- Cicero—Southwest

- Cleveland—North

- Constantia—North

- Hastings—West

- Jewell—Northeast

- Lakeport—South

- Lenox—South

- South Bay—Southeast

- Sullivan—South

- Sylvan Beach—East

- Verona—East

- Vienna—North

- West Monroe—Northwest

State parks

Namesakes

Oneida Lake is the namesake of Oneida Lacus, a hydrocarbon lake on the Saturnian moon Titan. That "lake" is composed of liquid methane and ethane,[7] and is located at 76.14°N and 131.83°W on Titan's globe.

Oneida County, Idaho is also named for the lake.

References

Notes

- ^ Ausubel, Seth (September 10, 2008). ""Section 319 Nonpoint Source Success Stories: New York: Oneida Lake" Projects Reduce Phosphorus in Lake". Environmental Protection Agency Meeting. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "New York - MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "Oneida History". Milwaukee Public Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Mills, Edward L. (2007). "Oneida Lake Profile" (PDF). Cornell University & Oneida Lake Association. Complete list of authors: Edward L. Mills, Kristen T. Holeck, James R. Jackson, Tony VanDeValk, Jeremy T. H. Coleman, and Lars G. Rudstam of the Cornell Biological Field Station, Rebecca L. Schneider of the Department of Natural Resources at Cornell University, Howard Goebel of the New York State Canal Corporation, and Jack Henke of the Oneida Lake Association.

- ^ Lord, Philip Jr. (2001). "The Covered Locks of Wood Creek". IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 27 (1): 5–15. JSTOR 40968547. This paper won the 2004 Robert M. Vogel Prize as the outstanding article in the previous three years published in IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology; see "2004 Robert M. Vogel Prize".

- ^ Whitford, Noble E.; Beal, Minnie M. (1906). "Chapter 16: The Oneida Lake Canal". History of the Canal System of the State of New York: Together with Brief Histories of the Canals of the United States and Canada. Brandow Printing Company. pp. 654–671.

- ^ Coustenis, A.; Taylor, F. W. (21 July 2008). Titan: Exploring an Earthlike World. World Scientific. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-981-281-161-5.

Further reading

- Barbagallo, Tricia (June 1, 2005). "Black Beach: The Mucklands of Canastota, New York" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2013. Retrieved 2012-07-12. From 1900 to 1970, a region near the southeast shore of Oneida Lake was "the onion capital of the world".

External links

- Oneida Lake View Webcam of Oneida Lake, North Shore

- NYCanals.com: A guide to boating on Oneida Lake and surrounding waterways.

- Oneida Lake Association