Celtic art

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

Celtic art is a difficult term to define, covering a huge expanse of time, geography and cultures. A case has been made for artistic continuity in Europe from the Bronze Age, and indeed the preceding Neolithic age; however archaeologists generally use "Celtic" to refer to the culture of the European Iron Age from around 1000 BC onwards, until the conquest by the Roman Empire of most of the territory concerned, and art historians typically begin to talk about "Celtic art" only from the La Tène period (broadly 5th to 1st centuries BC) onwards.[1] Early Celtic art is another term used for this period, stretching in Britain to about 150 AD.[2] The Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, which produced the Book of Kells and other masterpieces, and is what "Celtic art" evokes for much of the general public in the English-speaking world, is called Insular art in art history. This is the best-known part, but not the whole of, the Celtic art of the Early Middle Ages, which also includes the Pictish art of Scotland.[3]

Both styles absorbed considerable influences from non-Celtic sources, but retained a preference for geometrical decoration over figurative subjects, which are often extremely stylised when they do appear; narrative scenes only appear under outside influence.[4] Energetic circular forms, triskeles and spirals are characteristic. Much of the surviving material is in precious metal, which no doubt gives a very unrepresentative picture, but apart from Pictish stones and the Insular high crosses, large monumental sculpture, even with decorative carving, is very rare. Possibly the few standing male figures found, like the Warrior of Hirschlanden and the so-called "Lord of Glauberg", were originally common in wood.

Also covered by the term is the visual art of the Celtic Revival (on the whole more notable for literature) from the 18th century to the modern era, which began as a conscious effort by Modern Celts, mostly in the British Isles, to express self-identification and nationalism, and became popular well beyond the Celtic nations, and whose style is still current in various popular forms, from Celtic cross funerary monuments to interlace tattoos. Coinciding with the beginnings of a coherent archaeological understanding of the earlier periods, the style self-consciously used motifs closely copied from works of the earlier periods, more often the Insular than the Iron Age. Another influence was that of late La Tène "vegetal" art on the Art Nouveau movement.

Typically, Celtic art is ornamental, avoiding straight lines and only occasionally using symmetry, without the imitation of nature central to the classical tradition, often involving complex symbolism. Celtic art has used a variety of styles and has shown influences from other cultures in their knotwork, spirals, key patterns, lettering, zoomorphics, plant forms and human figures. As the archaeologist Catherine Johns put it: "Common to Celtic art over a wide chronological and geographical span is an exquisite sense of balance in the layout and development of patterns. Curvilinear forms are set out so that positive and negative, filled areas and spaces form a harmonious whole. Control and restraint were exercised in the use of surface texturing and relief. Very complex curvilinear patterns were designed to cover precisely the most awkward and irregularly shaped surfaces".[5]

Background

The ancient peoples now called "Celts" spoke a group of languages that had a common origin in the Indo-European language known as Common Celtic or Proto-Celtic. This shared linguistic origin was once widely accepted by scholars to indicate peoples with a common genetic origin in southwest Europe, who had spread their culture by emigration and invasion. Archaeologists identified various cultural traits of these peoples, including styles of art, and traced the culture to the earlier Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture. More recent genetic studies have indicated that various Celtic groups do not all have shared ancestry, and have suggested a diffusion and spread of the culture without necessarily involving significant movement of peoples.[6] The extent to which "Celtic" language, culture and genetics coincided and interacted during prehistoric periods remains very uncertain and controversial.

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

The term "Celt" was used in classical times as a synonym for the Gauls (Κελτοι, Celtae). Its English form is modern, attested from 1607. In the late 17th century the work of scholars such as Edward Lhuyd brought academic attention to the historic links between Gaulish and the Brythonic—and Goidelic—speaking peoples, from which point the term was applied not just to continental Celts but those in Britain and Ireland. Then in the 18th century the interest in "primitivism", which led to the idea of the "noble savage", brought a wave of enthusiasm for all things Celtic and Druidic. The "Irish revival" came after the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 as a conscious attempt to demonstrate an Irish national identity, and with its counterpart in other countries subsequently became the "Celtic Revival".

Pre-Celtic periods

The earliest archaeological culture that is conventionally termed Celtic, the Hallstatt culture (from "Hallstatt C" onwards), comes from the early European Iron Age, c. 800–450 BC. Nonetheless, the art of this and later periods reflects considerable continuity, and some long-term correspondences, with earlier art from the same regions, which may reflect the emphasis in recent scholarship on "Celticization" by acculturation among a relatively static population, as opposed to older theories of migrations and invasions. Megalithic art across much of the world uses a similar mysterious vocabulary of circles, spirals and other curved shapes, but it is striking that the most numerous remains in Europe are the large monuments, with many rock drawings left by the Neolithic Boyne Valley culture in Ireland, within a few miles of centres for Early Medieval Insular art some 4,000 years later. Other centres such as Brittany are also in areas that remain defined as Celtic today. Other correspondences are between the gold lunulas and large collars of Bronze Age Ireland and Europe and the torcs of Iron Age Celts, all elaborate ornaments worn round the neck. The trumpet shaped terminations of various types of Bronze Age Irish jewellery are also reminiscent of motifs popular in later Celtic decoration.

Iron Age; Early Celtic art

Unlike the rural culture of Iron Age inhabitants of the modern "Celtic nations", Continental Celtic culture in the Iron Age featured many large fortified settlements, some very large, for which the Roman word for "town", oppidum, is now used. The elites of these societies had considerable wealth, and imported large and expensive, sometimes frankly flashy, objects from neighbouring cultures, some of which have been recovered from graves. The work of the German émigré to Oxford, Paul Jacobsthal, remains the foundation of the study of the art of the period, especially his Early Celtic Art of 1944.[8]

The Halstatt culture produced art with geometric ornament, but marked by patterns of straight lines and rectangles rather than curves; the patterning is often intricate, and fills all the space available, and at least in this respect looks forward to later Celtic styles. Linguists are generally satisfied that the Halstatt culture originated among people speaking Celtic languages, but art historians often avoid describing Halstatt art as "Celtic".

As Halstatt society became increasingly rich and, despite being entirely land-locked in its main zone, linked by trade to other cultures, especially in the Mediterranean, imported objects in radically different styles begin to appear, even including Chinese silks. A famous example is the Greek krater from the Vix Grave in Burgundy, which was made in Magna Graecia (the Greek south of Italy) c. 530 BC, some decades before it was deposited. It is a huge bronze wine-mixing vessel, with a capacity of 1,100 litres.[9] Another huge Greek vessel in the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave is decorated with three recumbent lions lying on the rim, one of which is a replacement by a Celtic artist that makes little attempt to copy the Greek style of the others.[10] Forms characteristic of Hallstatt culture can be found as far from the main Central European area of the culture as Ireland, but mixed with local types and styles.[11]

Figures of animals and humans do appear, especially in works with a religious element. Among the most spectacular objects are "cult wagons" in bronze, which are large wheeled trolleys containing crowded groups of standing figures, sometimes with a large bowl mounted on a shaft at the centre of the platform, probably for offerings to gods; a few examples have been found in graves. The figures are relatively simply modelled, without much success in detailed anatomical naturalism compared to cultures further south, but often achieving an impressive effect. There are also a number of single stone figures, often with a "leaf crown" — two flattish rounded projections, "resembling a pair of bloated commas", rising behind and to the side of the head, probably a sign of divinity.[12]

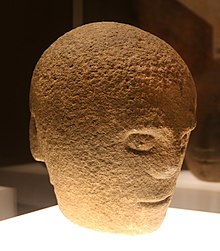

Human heads alone, without bodies, are far more common, frequently appearing in relief on all sorts of objects. In the La Tène period faces often (along with bird's heads) emerge from decoration that at first looks abstract, or plant-based. Games are played with faces that change when they are viewed from different directions. In figures showing the whole body, the head is often over-large. There is evidence that the human head had a special importance in Celtic religious beliefs.[13]

The most elaborate ensembles of stone sculpture, including reliefs, come from southern France, at Roquepertuse and Entremont, close to areas colonized by the Greeks. It is possible that similar groups in wood were widespread. Roquepertuse seems to have been a religious sanctuary, whose stonework includes what are thought to have been niches where the heads or skulls of enemies were placed. These are dated to the 3rd century BC, or sometimes earlier.

In general, the number of high-quality finds is not large, especially when compared to the number of survivals from the contemporary Mediterranean cultures, and there is a very clear division between elite objects and the much plainer goods used by the majority of the people. There are many torcs and swords (the La Tène site produced over 3,000 swords, apparently votive offerings[14]), but the best-known finds, like the Czech head above, the shoe plaques from Hochdorf and the Waterloo Helmet, often have no similar other finds for comparison. Clearly religious content in art is rare, but little is known about the significance that most of the decoration of practical objects had for its makers, and the subject and meaning of the few objects without a practical function is equally unclear.

Hallstatt gallery

- Late Hallstatt gold collar from Austria, c. 550 BC

- Gold shoe plaques from the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave, Germany, c. 530 BC

- Pottery from Heuneburg, Germany

- Hallstatt culture ceramic bowl, from a grave in Alburg - Hochwegfeld, Germany.

- Decorated bent sword, part of the finds in a noble's grave at Oss (The Netherlands). Circa 826-600BC.

- Axehead with decorative figure, 800-600 BC

- Pottery decorated with incisions and paint, circa 600 BC

La Tène style

About 500 BC the La Tène style, named after a site in Switzerland, appeared rather suddenly, coinciding with some kind of societal upheaval that involved a shift of the major centres in a north-westerly direction. The central area where rich sites are especially found is in northern France and western Germany, but over the next three centuries the style spread very widely, as far as Ireland, Italy[15] and modern Hungary. In some places the Celts were aggressive raiders and invaders, but elsewhere the spread of Celtic material culture may have involved only small movements of people, or none at all. Early La Tène style adapted ornamental motifs from foreign cultures into something distinctly new; the complicated brew of influences including Scythian art and that of the Greeks and Etruscans among others. The occupation by the Persian Achaemenid Empire of Thrace and Macedonia around 500 BC is a factor of uncertain importance.[16] La Tène style is "a highly stylised curvilinear art based mainly on classical vegetable and foliage motifs such as leafy palmette forms, vines, tendrils and lotus flowers together with spirals, S-scrolls, lyre and trumpet shapes".[17]

The most lavish objects, whose imperishable materials tend to mean they are the best preserved other than pottery, do not refute the stereotypical views of the Celts that are found in classical authors, where they are represented as mainly interested in feasting and fighting, as well as ostentatious display. Society was dominated by a warrior aristocracy and military equipment, even if in ceremonial versions, and containers for drink, represent most of the largest and most spectacular finds, other than jewellery.[18] Unfortunately for the archaeologist, the rich "princely" burials characteristic of the Hallstatt period greatly reduce, at least partly because of a change from inhumation burials to cremation.[19]

The torc was evidently a key marker of status and very widely worn, in a range of metals no doubt reflecting the wealth and status of the owner. Bracelets and armlets were also common.[20] An exception to the general lack of depictions of the human figure, and of the failure of wooden objects to survive, are certain water sites from which large numbers of small carved figures of body parts or whole human figures have been recovered, which are assumed to be votive offerings representing the location of the ailment of the supplicant. The largest of these, at Source-de-la-Roche, Chamalières, France, produced over 10,000 fragments, mostly now at Clermont-Ferrand.[21]

Several phases of the style are distinguished, under a variety of names, including numeric (De Navarro) and alphabetic series. Generally, there is broad agreement on how to demarcate the phases, but the names used differ, and that they followed each other in chronological sequence is now much less certain. In a version of Jacobsthal's division, the "early" or "strict" phase, De Navarro I, where the imported motifs remain recognisable, is succeeded by the "vegetal", "Continuous Vegetal", "Waldalgesheim style", or De Navarro II, where ornament is "typically dominated by continuously moving tendrils of various types, twisting and turning in restless motion across the surface".[12]

After about 300 BC the style, now De Navarro III, can be divided into "plastic" and "sword" styles, the latter mainly found on scabbards and the former featuring decoration in high relief. One scholar, Vincent Megaw, has defined a "Disney style" of cartoon-like animal heads within the plastic style, and also an "Oppida period art, c 125–c 50 BC". De Navarro distinguishes the "insular" art of the British Isles, up to about 100 BC, as Style IV, followed by a Style V,[22] and the separateness of Insular Celtic styles is widely recognised.[23]

The often spectacular art of the richest earlier Continental Celts, before they were conquered by the Romans, often adopted elements of Roman, Greek and other "foreign" styles (and possibly used imported craftsmen) to decorate objects that were distinctively Celtic. So a torc in the rich Vix Grave terminates in large balls in a way found in many others, but here the ends of the ring are formed as the paws of a lion or similar beast, without making a logical connection to the balls, and on the outside of the ring two tiny winged horses sit on finely worked plaques. The effect is impressive but somewhat incongruous compared to an equally ostentatious British torc from the Snettisham Hoard that is made 400 years later and uses a style that has matured and harmonized the elements making it up. The 1st century BC Gundestrup cauldron, is the largest surviving piece of European Iron Age silver (diameter 69 cm, height 42 cm), but though much of its iconography seems clearly to be Celtic, much of it is not, and its style is much debated; it may well be of Thracian manufacture. To further confuse matters, it was found in a bog in north Denmark.[24] The Agris Helmet in gold leaf over bronze clearly shows the Mediterranean origin of its decorative motifs.

By the 3rd century BC Celts began to produce coinage, imitating Greek and later Roman types, at first fairly closely, but gradually allowing their own taste to take over, so that versions based on sober classical heads sprout huge wavy masses of hair several times larger than their faces, and horses become formed of a series of vigorously curved elements.

A form apparently unique to southern Britain was the mirror with a handle and complex decoration, mostly engraved, on the back of the bronze plate; the front side being highly polished to act as the mirror. Each of the more than 50 mirrors found has a unique design, but the essentially circular shape of the mirror presumably dictated the sophisticated abstract curvilinear motifs that dominate their decoration.[25]

Despite the importance of Ireland for Early Medieval Celtic art, the number of artefacts showing La Tène style found in Ireland is small, though they are often of very high quality. Some aspects of Hallstatt metalwork had appeared in Ireland, such as scabbard chapes, but the La Tène style is not found in Ireland before some point between 350 and 150 BC, and until the latter date is mostly found in modern Northern Ireland, notably in a series of engraved scabbard plates. Thereafter, despite Ireland remaining outside the Roman Empire that engulfed the Continental and British Celtic cultures, Irish art is subject to continuous influence from outside, through trade and probably periodic influxes of refugees from Britain, both before and after the Roman invasion. It remains uncertain whether some of the most notable objects found from the period were made in Ireland or elsewhere, as far away as Germany and Egypt in specific cases.[26]

But in Scotland and the western parts of Britain where the Romans and later the Anglo-Saxons were largely held back, versions of the La Tène style remained in use until it became an important component of the new Insular style that developed to meet the needs of newly Christianized populations. Indeed, in northern England and Scotland most finds post-date the Roman invasion of the south.[27] However, while there are fine Irish finds from the 1st and 2nd centuries, there is little or nothing in La Tène style from the 3rd and 4th centuries, a period of instability in Ireland.[28]

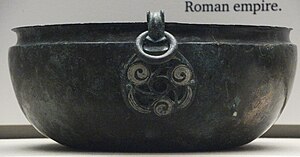

After the Roman conquests, some Celtic elements remained in popular art, especially Ancient Roman pottery, of which Gaul was actually the largest producer, mostly in Italian styles, but also producing work in local taste, including figurines of deities and wares painted with animals and other subjects in highly formalized styles. Roman Britain produced a number of items using Roman forms such as the fibula but with La Tène style ornament, whose dating can be difficult,[29] for example a "hinged brass collar" from around the time of the Roman conquest shows Celtic decoration in a Roman context.[30] Britain also made more use of enamel than most of the Empire, and on larger objects, and its development of champlevé technique was probably important to the later Medieval art of the whole of Europe, of which the energy and freedom derived from Insular decoration was an important element. Enamel decoration on penannular brooches, dragonesque brooches,[31] and hanging bowls appears to demonstrate a continuity in Celtic decoration between works like the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan and the flowering of Christian Insular art from the 6th century onwards.

- Continental examples

- Gold mounts on a bowl, adapting Mediterranean motifs, Germany, c. 420BC

- Disc brooch, France, 4th century BC

- Parade Helmet, Agris, France, 350 BC, decorated in a mixture of Mediterranean styles

- Bronze ankle rings, hollow cast, with ornament knobs, Germany, 3rd century BC

- British examples

- The Battersea Shield, England, 350-50 BC, for display rather than combat.

- The Wandsworth Shield-boss, in the "plastic" style

- Gold torc, 75 BC, found in the Needwood Forest, in the UK

- Bronze mount in British "Disney style", 10 cm high, 1st century AD

- The Waterloo Helmet, a unique find, probably not worn in battle.

Early Middle Ages

Post-Roman Ireland and Britain

Celtic art in the Middle Ages was practiced by the peoples of Ireland and parts of Britain in the 700-year period from the Roman withdrawal from Britain in the 5th century, to the establishment of Romanesque art in the 12th century. Through the Hiberno-Scottish mission the style was influential in the development of art throughout Northern Europe.

In Ireland an unbroken Celtic heritage existed from before and throughout the Roman era of Britain, which had never reached the island, though in fact Irish objects in La Tène style are very rare from the Late Roman period. The 5th to 7th centuries were a continuation of late Iron Age La Tène art, with also many signs of the Roman and Romano-British influences that had gradually penetrated there.[32] With the arrival of Christianity, Irish art was influenced by both Mediterranean and Germanic traditions, the latter through Irish contacts with the Anglo-Saxons, creating what is called the Insular or Hiberno-Saxon style, which had its golden age in the 8th and early 9th centuries before Viking raids severely disrupted monastic life. Late in the period Scandinavian influences were added through the Vikings and mixed Norse-Gael populations, then original Celtic work came to end with the Norman invasion in 1169–1170 and the subsequent introduction of the general European Romanesque style.[citation needed]

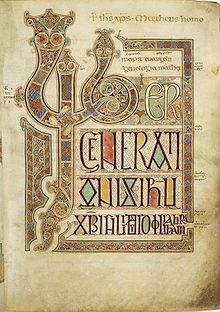

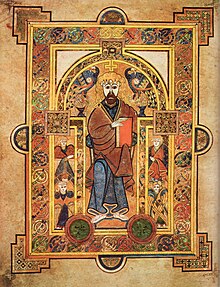

In the 7th and 9th centuries Irish Celtic missionaries travelled to Northumbria in Britain and brought with them the Irish tradition of manuscript illumination, which came into contact with Anglo-Saxon metalworking knowledge and motifs. In the monasteries of Northumbria these skills fused and were probably transmitted back to Scotland and Ireland from there, also influencing the Anglo-Saxon art of the rest of England. Some of the metalwork masterpieces created include the Tara Brooch, the Ardagh Chalice and the Derrynaflan Chalice. New techniques employed were filigree and chip carving, while new motifs included interlace patterns and animal ornamentation. The Book of Durrow is the earliest complete insular script illuminated Gospel Book and by about 700, with the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Hiberno-Saxon style was fully developed with detailed carpet pages that seem to glow with a wide palette of colours. The art form reached its peak in the late 8th century with the Book of Kells, the most elaborate Insular manuscript. Anti-classical Insular artistic styles were carried to mission centres on the Continent and had a continuing impact on Carolingian, Romanesque and Gothic art for the rest of the Middle Ages.

In the 9th and 11th century plain silver became a popular medium in Anglo-Saxon England, probably because of the increased amount in circulation due to Viking trading and raiding, and it was during this time a number of magnificent silver penannular brooches were created in Ireland. Around the same time manuscript production began to decline, and although it has often been blamed on the Vikings, this is debatable given the decline began before the Vikings arrived. Sculpture began to flourish in the form of the "high cross", large stone crosses that held biblical scenes in carved relief. This art form reached its apex in the early 10th century and has left many fine examples such as Muiredach's Cross at Monasterboice and the Ahenny High Cross.

The impact of the Vikings on Irish art is not seen until the late 11th century when Irish metal work begins to imitate the Scandinavian Ringerike and Urnes styles, for example the Cross of Cong and Shrine of Manchan. These influences were found not just in the Norse centre of Dublin, but throughout the countryside in stone monuments such as the Dorty Cross at Kilfenora and crosses at the Rock of Cashel.[33]

Some Insular manuscripts may have been produced in Wales, including the 8th century Lichfield Gospels and Hereford Gospels.[34] The late Insular Ricemarch Psalter from the 11th century was certainly written in Wales, and also shows strong Viking influence.

Art from historic Dumnonia, modern Cornwall, Devon, Somerset and Brittany on the Atlantic seaboard is now fairly sparsely attested and hence less well known as these areas later became incorporated into England (and France) in the medieval and Early Modern period.[35] However archaeological studies at sites such as Cadbury Castle, Somerset,[36] Tintagel,[37] and more recently at Ipplepen[38] indicate a highly sophisticated largely literate society with strong influence and connections with both the Byzantine Mediterranean as well as the Atlantic Irish, and British in Wales and the 'Old North'. Many crosses, memorials and tombstones such as King Doniert's Stone,[39] the Drustanus stone and the notorious Artognou stone show evidence for a surprisingly cosmopolitan sub-Roman population speaking and writing in both Brittonic and Latin and with at least some knowledge of Ogham indicated by several extant stones in the region. Breton and especially Cornish manuscripts are exceedingly rare survivals but include the Bodmin manumissions[40] demonstrating a regional form of the Insular style.

Picts (Scotland)

From the 5th to the mid-9th centuries, the art of the Picts is primarily known through stone sculpture, and a smaller number of pieces of metalwork, often of very high quality; there are no known illuminated manuscripts. The Picts shared modern Scotland with a zone of Irish cultural influence on the west coast, including Iona, and the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria to the south. After Christianization, Insular styles heavily influenced Pictish art, with interlace prominent in both metalwork and stones.

The heavy silver Whitecleuch Chain has Pictish symbols on its terminals, and appears to be an equivalent to a torc. The symbols are also found on plaques from the Norrie's Law hoard. These are thought to be relatively early pieces. The St Ninian's Isle Treasure of silver penannular brooches, bowls and other items comes from off the coast of Pictland and is often regarded as mostly of Pictish manufacture, representing the best survival of Late Pictish metalwork, from about 800 AD.

Pictish stones are assigned by scholars to 3 classes. Class I Pictish stones are unshaped standing stones incised with a series of about 35 symbols which include abstract designs (given descriptive names such as crescent and V-rod, double disc and Z-rod, 'flower' and so on by researchers); carvings of recognisable animals (bull, eagle, salmon, adder and others), as well as the Pictish Beast, and objects from daily life (a comb, a mirror). The symbols almost always occur in pairs, with in about one-third of cases the addition of the mirror, or mirror and comb, symbol, below the others. This is often taken to symbolise a woman. Apart from one or two outliers, these stones are found exclusively in north-east Scotland from the Firth of Forth to Shetland. Good examples include the Dunnichen and Aberlemno stones (Angus), and the Brandsbutt and Tillytarmont stones (Aberdeenshire).

Class II stones are shaped cross-slabs carved in relief, or in a combination of incision and relief, with a prominent cross on one, or in rare cases two, faces. The crosses are elaborately decorated with interlace, key-pattern or scrollwork, in the Insular style. On the secondary face of the stone, Pictish symbols appear, often themselves elaborately decorated, accompanied by figures of people (notably horsemen), animals both realistic and fantastic, and other scenes. Hunting scenes are common, Biblical motifs less so. The symbols often appear to 'label' one of the human figures. Scenes of battle or combat between men and fantastic beasts may be scenes from Pictish mythology. Good examples include slabs from Dunfallandy and Meigle (Perthshire), Aberlemno (Angus), Nigg, Shandwick and Hilton of Cadboll (Easter Ross).

Class III stones are in the Pictish style, but lack the characteristic symbols. Most are cross-slabs, though there are also recumbent stones with sockets for an inserted cross or small cross-slab (e.g. at Meigle, Perthshire). These stones may date largely to after the Scottish takeover of the Pictish kingdom in the mid 9th century. Examples include the sarcophagus and the large collection of cross-slabs at St Andrews (Fife).

The following museums have important collections of Pictish stones: Meigle (Perthshire), St Vigeans (Angus) and St Andrew's Cathedral (Fife) (all Historic Scotland), the Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh (which also exhibits almost all the major pieces of surviving Pictish metalwork), the Meffan Institute, Forfar (Angus), Inverness Museum, Groam House Museum, Rosemarkie and Tarbat Discovery Centre, Portmahomack (both Easter Ross) and The Orkney Museum in Kirkwall.

Celtic revival

The revival of interest in Celtic visual art came sometime later than the revived interest in Celtic literature. By the 1840s reproduction Celtic brooches and other forms of metalwork were fashionable, initially in Dublin, but later in Edinburgh, London and other countries. Interest was stimulated by the discovery in 1850 of the Tara Brooch, which was seen in London and Paris over the next decades. The late 19th century reintroduction of monumental Celtic crosses for graves and other memorials has arguably been the most enduring aspect of the revival, one that has spread well outside areas and populations with a specific Celtic heritage. Interlace typically features on these and has also been used as a style of architectural decoration, especially in America around 1900, by architects such as Louis Sullivan, and in stained glass and wall stenciling by Thomas A. O'Shaughnessy, both based in Chicago with its large Irish-American population. The "plastic style" of early Celtic art was one of the elements feeding into Art Nouveau decorative style, very consciously so in the work of designers like the Manxman Archibald Knox, who did much work for Liberty & Co.

The Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland embraced the Celtic style early on, but began to back away in the 1920s. The governor of the National Gallery of Ireland, Thomas Bodkin, writing in The Studio magazine in 1921, drew attention to the decline in Celtic ornament in the Sixth Exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland said, "National art all over the world has burst long ago, the narrow boundaries within which it is cradled, and grows more cosmopolitan in spirit with each succeeding generation." George Atkinson, writing the foreword to the catalogue of that same exhibit emphasized the society's disapproval of any undue emphasis on Celtic ornament at the expense of good design. "Special pleading on behalf of the national traditional ornament is no longer justifiable.”The style had served the nationalist cause as an emblem of a distinct Irish culture, but soon intellectual fashions abandoned Celtic art as nostalgically looking backwards.[41]

Interlace, which is still seen as a "Celtic" form of decoration—somewhat ignoring its Germanic origins and equally prominent place in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian medieval art—has remained a motif in many forms of popular design, especially in Celtic countries, and above all Ireland, where it remains a national style signature. In recent decades it has been used worldwide in tattoos, and in various contexts and media in fantasy works with a quasi-Dark Ages setting. The Secret of Kells is an animated feature film of 2009 set during the creation of the Book of Kells which makes much use of Insular design.

By the 1980s a new Celtic Revival had begun, which continues to this day. Often this late 20th-century movement is referred to as the Celtic Renaissance.[42] By the 1990s the number of new artists, craftsmen, designers and retailers specializing in Celtic jewelry and crafts was rapidly increasing. The Celtic Renaissance has been an international phenomenon, with participants no longer confined to just the Old-World Celtic countries.[43]

June 9 was designated International Day of Celtic Art in 2017 by a group of contemporary Celtic artists and enthusiasts. The day is an occasion for exhibits, promotions, workshops, demonstrations and gatherings.[44] From June 6 to 9, 2019 the First International Day of Celtic Art Conference was held in Andover, New York. Thirty artists, craftsmen and scholars from Scotland, Ireland and from across the United States and Canada attended. The second IDCA Conference was held at The Saint Patrick Centre in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland, from June 8 to 11, 2023. Conference organizers will continue the series as a biannual event.

Celtic art types and terms

- Hanging bowl. According to the traditional theory, these were created by Celtic craftsmen during the time of the Anglo-Saxon conquests of England. They were based on a Roman design, usually made of copper alloy with 3 or 4 suspension loops along the top rim, from which they were designed to be hung, perhaps from roof-beams or within a tripod. Their art-historical interest mainly derives from the round decorated plaques or "escutcheons", often with enamel, that most have along their rims. Some of the finest examples are found in the hoard at Sutton Hoo (625) which are enamelled. The knowledge of their manufacture spread to Scotland and Ireland in the 8th century. However, although their styles continue popular Romano-British traditions, the assumption that they were made in Ireland is now questioned. The few fragments excavated from the 7th-century Benty Grange hanging bowl are typical of many survivals.

- Carpet page. An illuminated manuscript page decorated entirely in ornamentation. In Hiberno-Saxon tradition this was a standard feature of Gospel books, with one page as an introduction to each Gospel. Usually made in a geometric or interlace pattern, often framing a central cross. The earliest known example is the 7th century Bobbio Orosius.

- High cross. A tall stone standing cross, usually of Celtic cross form. Decoration is abstract often with figures in carved relief, especially crucifixions, but in some cases complex multi-scene schemes. Most common in Ireland, but also in Great Britain and near continental mission centres.

- Pictish stone. A cross-slab—a rectangular slab of rock with a cross carved in relief on the slab face, with other pictures and shapes carved throughout. Organised into three Classes, based on the period of origin.

- Insular art or the Hiberno-Saxon style, from the 6th to 9th centuries. The fusion of pre-Christian Celtic and Anglo-Saxon metalworking styles, applied to the new form of the religious illuminated manuscript, as well as sculpture and secular and church metalwork. Also includes influences from post-classical Europe, and later Viking decorative styles. The peak of the style in manuscripts occurred when Irish Celtic missionaries traveled to Northumbria in the 7th and 8th centuries. Produced some of the most outstanding Celtic art of the Middle Ages in illuminated manuscripts, metalworking and sculpture.

- Celtic calendar. The oldest material Celtic calendar is the fragmented Gaulish Coligny calendar from the 1st century BC or AD.

See also

Notes

- ^ Megaws, for example; see their introductory section, where they explain the situation & that their article will only cover the La Tène period.

- ^ "Technologies of Enchantment: Early Celtic Art in Britain". British Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-08-04. It is also used by Jacobsthal; however the equivalent "Late Celtic art" for Early Medieval work is much rarer, and "Late Celtic art" can also mean the later part of the prehistoric period.

- ^ Laings, 6–12

- ^ Megaws

- ^ Johns, 24

- ^ Sykes, Brian "Saxons, Vikings, and Celts" (2008) W.W. Norton & Co. NY, pp. 281–284.

- ^ "Carved stone ball" Archived 2013-07-02 at the Wayback Machine. National Museums of Scotland. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ Raftery, 184–185; for a preview or summary, see Jacobsthal (1935), and for a long summary in a review see Hawkes.

- ^ Le Musée du Pays Châtillonnais Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Vix Krater (in French).

- ^ Boardman

- ^ NMI, 125–126

- ^ a b Raftery, 186

- ^ Green, 121–126, 138–142

- ^ British Museum highlights Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, La Tène

- ^ Vitali, Daniele (1996). "Manufatti in ferro di tipo La Tène in area italiana : le potenzialità non sfruttate". Mélanges de l'École Française de Rome. Antiquité. 108 (2): 575–605. doi:10.3406/mefr.1996.1954.

- ^ Sandars, 226–233; Laings, 34–35

- ^ NMI, 126

- ^ Green, Chapters 2 and 3

- ^ Green, 21–26; 72–73

- ^ Green, 72–79

- ^ Megaws; in the Musée Bargoin.

- ^ Megaws (Oppida period); Megaw and Megaw, 10–11, with more detail on these schemes; Laings, 41–42, 94–95; also see Harding, 119

- ^ Sandars, 233 and Chapter 9; Laings, 94

- ^ Bergquist, A K & Taylor, T F (1987), “The origin of the Gundestrup cauldron”, Antiquity 61: 10–24

- ^ Celtic mirrors website Archived 2010-01-26 at the Wayback Machine, with good pictures and information.

- ^ NMI, 127–133

- ^ Garrow, 2, google books Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NMI, 134

- ^ Laings, 125–130

- ^ Hinged brass collar Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, British Museum

- ^ "Dragonesque brooch". britishmuseum.org. British Museum. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ NMI, 134, 172–173

- ^ NMI, 216–219;St Fachtnan, Kilfenora Archived 2019-06-01 at the Wayback Machine in the Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland

- ^ Peter Lord, Medieval Vision: The Visual Culture of Wales. University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 2003, pg. 25; see the Wikipedia articles on the two manuscripts for further references.

- ^ archaeologydataservice.ac.uk http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20151203105658/http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-769-1%2Fdissemination%2Fpdf%2Fvol33%2F33_001_006.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-03.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Alcock, L. 1995 Cadbury Castle: The Early Medieval Archaeology, University of Wales; see also the South Cadbury Environs Project Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University

- ^ Tintagel Region Archaeological Landscape Archived 2015-11-24 at the Wayback Machine, University of Winchester

- ^ The Ipplepen project Archived 2016-02-23 at the Wayback Machine, University of Exeter

- ^ "History of King Doniert's Stone – English Heritage". www.english-heritage.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Bodmin Gospels, British Library Archived 2016-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, Additional MS 9381

- ^ Stephen Walker, The Modern History of Celtic Jewellery, Walker Metalsmiths, Andover, NY 2013

- ^ Michael Carroll, post 1170 in Discussion of Celtic Art, Yahoo Groups 2001, accessed Aug. 6, 2016

- ^ Walker, pg 12–13

- ^ "International Celtic Art Day – Celtic Life International". Archived from the original on 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

References

- Garrow, Duncan (ed), Rethinking Celtic Art, 2008, Oxbow Books, ISBN 1842173189, 9781842173183, google books

- Green, Miranda, Celtic Art, Reading the Messages, 1996, The Everyman Art Library, ISBN 0-297-83365-0

- Harding, Dennis, William. The archaeology of Celtic art, Routledge, 2007, ISBN 0-415-35177-4, ISBN 978-0-415-35177-5, Google books

- Hawkes, C.F.C., review of Early Celtic Art by Paul Jacobsthal, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 37, Parts 1 and 2 (1947), pp. 191–198, JSTOR

- Jacobsthal, Paul (1935), "Early Celtic Art", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 67, No. 390 (Sep., 1935), pp. 113–127, JSTOR

- Johns, Catherine, The Jewellery of Roman Britain: Celtic and Classical Traditions, Routledge, 1996, ISBN 1-85728-566-2, ISBN 978-1-85728-566-6, Google books

- Laing, Lloyd and Jenifer. Art of the Celts, Thames and Hudson, London 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- "NMI": Wallace, Patrick F., O'Floinn, Raghnall eds. Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities ISBN 0-7171-2829-6

- Megaw, Ruth and Vincent (2001). Celtic Art. ISBN 0-500-28265-X

- "Megaws": Megaw, Ruth and Vincent, "Celtic Art", Oxford Art Online, accessed October 7, 2010

- Raftery, Barry, "La Tène Art", in Bogucki, Peter I. and Crabtree, Pam. J.: Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.--A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian world, 2004, Charles Scribner's Sons, ISBN 0-684-80668-1, ISBN 978-0-684-80668-6. online text (slightly shortened)

- Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

Further reading

- Boltin, Lee, ed.: Treasures of Early Irish Art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.: From the Collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Royal Irish Academy, Trinity College, Dublin, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977, ISBN 0-87099-164-7, fully available online.

- Bain, George: Celtic Art, The Methods of Construction, Lavishly Illustrated with Line Drawings and Photographs: Dover Publishing, New York, 1973, ISBN 0-486-22923-8, which is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by William MacLellan & Co., Ltd., Glasgow, 1951.

External links

- The Celtic art database, hosted by the British Museum. "A comprehensive database of all Celtic art found in Britain to date. This includes excavated finds and finds recently reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme", excel spreadsheet, last updated August 2010. For summaries, see Garrow, chapter 2.

- Celtic Art & Culture from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Insular Celtic bronze mirrors

- "Bearing the truth about Celtic art: Kunst der Kelten in Bern" Archived 2010-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, Review by Vincent Megaw of 2009 exhibition, Antiquity online.