Gender and sexual minorities in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, which existed from the 14th century until the early 20th century, had a complex and varied approach to issues related to sexuality and gender, including those of gender and sexual minorities.

Concepts such as gay, lesbian or transgender did not exist in the Ottoman era. Homosexuality was de jure governed by a blend of Qanun (sultanic law) and Islamic religious laws, which translated to negative legalistic perspectives, but also lenient-to-nonexistent enforcement. Therefore, negative perspectives often did not lead to legal sanctions, with rare exceptions. Public norms exhibited fluid gender expressions (particularly for younger males), and attitudes toward same-sex relationships were diverse, often categorized by age and expected roles. Literature and art flourished as significant mediums for discussing gender and sexuality, with Ottoman poets openly exploring same-sex love in the arts until the 19th century, when Westernization led to the stigmatization of homosexuality, potentially influencing the censorship of certain literary scenes.

The 19th-century ushered in transformative changes marked by Westernization; these changes largely stigmatized homosexuality. The 1858 Ottoman Penal Code is a pivotal moment, often cited as signaling private decriminalization. However, previous laws against homosexuality were rarely invoked by the Ottomans, and this liberalization came amid heightening heteronormativity and anxieties about open same-sex expression among men, leading many scholars to question the validity of the "decriminalization" paradigm used for the Ottoman Empire.

Beyond its borders, the perception of homosexuality in the Ottoman Empire became entwined with Orientalist tropes, perpetuating stereotypes of sexual perversion in Western discourse. This representation reflected attempts to assert the moral superiority of Christendom over the Muslim world.

History and legal status

The late Ottoman Empire was governed by the authority of the Qanun (sultanic law), based on Hanafi law of the sharīʿah.[1][2] While legal perspectives on homosexuality were negative, actual legal persecution was rare.[3][4][5] Public perceptions of homosexual acts and gender norms were varied and often ambivalent; some acts were seen as more normative than others, and some could be celebrated in literature.[3][4] These norms changed drastically in the 19th century, during the Westernization and collapse of the empire.[4]

Mukhannathun (مخنثون "effeminate ones", "ones who resemble women", singular mukhannath) was a term used in Classical Arabic to refer to effeminate men or people of ambiguous sex characteristics who appeared feminine or functioned socially in roles typically carried out by women.[6] According to the Iranian scholar Mehrdad Alipour, "in the premodern period, Muslim societies were aware of five manifestations of gender ambiguity: This can be seen through figures such as the khasi (eunuch), the hijra, the mukhannath, the mamsuh and the khuntha (hermaphrodite/intersex)."[7] Although mukhannathun were initially considered to desire females, they were later considered to desire males instead and became associated with homosexuality,[8] particularly the receptive partner in gay sexual practices.[9]

Pre-modern period

For men, the terms gulampare was used to mean "male-lover" (men loving men), and zenpare to mean "woman-lover" (men loving women).[10] Concepts of 'lesbian' or 'gay' identities did not exist. Instead, identity was based on sexual roles, i.e. whether one was considered active or passive.[3] Boys and men without beards (emred) were considered sexually desirable and feminine, which allowed them to be "penetrable" and the objects of desire for older men.[11] Will Roscoe and Stephen O. Murray contend that the division between gender variance and sexual object choice occurred in the early 20th century. Until the late 1940s, sexual minoritization was associated with being a non-masculine man or a non-feminine woman, while those considered "normal" were 'masculine' men and 'feminine' women. This historical view of homosexuality, they say, was prevalent in the Muslim world, particularly during the medieval period (the Islamic Golden Age).[12]

Generally, adolescent men were socially permitted to desire older men or women. After puberty, they were expected to desire young boys or women. Being in both roles could have led to social censure.[3] There is evidence, however, that egalitarian same-sex relations also occurred.[13]

Guillaume de Vaudoncourt wrote that Ali Pasha (the ruler of Ottoman-controlled Albania 1788–1822) was "almost exclusively given up to the Socratic pleasures, and for this purpose keeps up a seraglio of youths, from among whom he selects his confidants, and even his principal officers";[14] his son Veli Pasha was also said to share an "appetite for boys".[15] While in most cases, these relationships were temporary, Ottoman Albania at this time also had a concept similar to same-sex unions, among both Muslim and Christian communities.[16]

The legal concept of gender was binary, but gender expression could be more fluid in some locations and contexts. Köçek was a term for male dancers;[10] Turkish musicologist Şehvar Beşiroğlu notes that köçekler (plural of köçek) were typically handsome, young, and effeminate.[17] They usually dressed in feminine clothes and were employed as entertainers.[18] Men watching the köçekler would allegedly go wild, breaking their glasses, shouting themselves voiceless, or fighting and sometimes killing each other vying for the opportunity to rape, molest, or otherwise force the young men into sexual servitude.[19] This association with sexual exploitation resulted in suppression of the practice under Sultan Abdulmejid I.[20] As gender and sexual roles were conflated at this time, the feminine köçek identity was associated with being the receptive partner in homosexual intercourse, which was seen as feminine or feminizing.[21]

In his work Sexuality in Islam, Abdelwahab Bouhdiba cites the hamam (public bathhouses) as a place where homosexual encounters in general can take place.[22][23] He notes that some historians found evidence of hamam as spaces for sexual expression among women, which they believed was a result of the universality of nudity in these spaces. Hamam have also been associated with male homosexuality over the centuries and up to the present day.[22][24][25]

Westernization

The 19th-century brought complex changes, marked by heightened heteronormativity, despite de jure changes that could be seen as liberalizing.[4][26] In 1858, Ottoman society constructed a reform to their penal code that was fairly similar to the 1810 French Penal Code. The 1858 Ottoman Penal Code stated the following:

Art. 202—The person who dares to commit the abominable act publicly contrary to modesty and sense of shame is to be imprisoned for from three months to one year and a fine of from one Mejidieh gold piece to ten Mejidieh gold pieces is to be levied.

— Penal Code of the Ottoman Empire, 1858.[27]

This law, which nullified earlier rulings, is often cited as private decriminalization. However, as the previous laws were very rarely invoked and this reform was implemented during a time of heightening heteronormativity, some have claimed the 'criminalization-decriminalization' paradigm as inappropriate for the Ottoman Empire.[26]

According to Dror Ze'evi, European pressure shaped the nineteenth century, resulting in the reinterpretation of local cultural material and traditions.[28] European travelers denounced the Ottomans for their ostensibly 'corrupt' sexual proclivities, and Ze'evi argues that the literate classes of the empire responded by 'reinventing' their own sexual norms.[28] A new discourse was created to assert an idealized, heteronormative Ottoman world that surpassed Europe in its ostensible sexual 'morality', while local practices and discourses were actively suppressed to align with this invented tradition.[28] Spurred in large part by these changes, homosexual contact started to decline in the late 19th-century, and the focus of desire turned to young girls. Ahmed Cevdet Pasha stated:

"Woman-lovers (zendost) have increased in number, while boy-beloveds (mahbub) have decreased. It is as if the People of Lot have been swallowed by the earth. The love and affinity that were, in Istanbul, notoriously and customarily directed towards young men have now been redirected towards girls, in accordance with the state of nature."[29]

Research shows that the decline is in close relationship to increasing criminalization of homosexuality in the Western world at the time, which was followed by repression of gender and sexual minorities.[30]

Literature and art

Ottoman literary culture, particularly poetry, openly discussed gender and sexuality (including same-sex love and desire) until the 19th century. Various poets debated the most beautiful form of love, whether female or male. Some poets focused only on the love between men and women, some on the love between women, and some only on love between men.[31]

The most preferred form of writing and poetry in classical culture was within traditional Sufi literature as well as the classical gazel. The love of God was sometimes likened by male poets to the love of other males;[32][33] Yahya bey Dukagjini states in his poems that he does not like mas̲navī, which use love of the opposite sex instead of love of the same sex as the basis of love stories. According to him, homoerotic love is superior and purer than cross-gender love.[34] Homoerotic metaphors in poetry were often preferred due to the segregation of males and females,[35] but these did not necessarily express homosexual desires.[33]

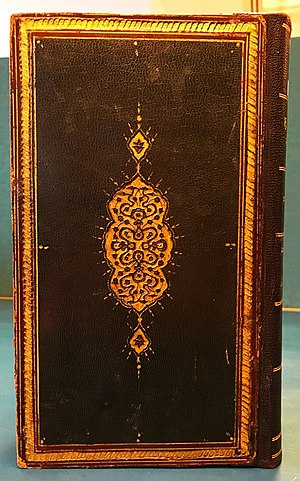

One of the most famous writers of homoerotic literature in the Ottoman Empire was Enderûnlu Fâzıl.[36] Fâzıl wrote erotically about the beauty of men from different nations in Hubânnâme (Book of [Male] Beauties). Fâzil's Zenânnâme (Book of Women) describes the characteristics of the women of different nationalities. There was a long-standing belief that the homoerotic poems were exclusively pederastic. While this was the norm, variations from this existed, including relationships between post-pubescent males of similar ages, or of younger males taking on the insertive role in anal intercourse.[37][38] The 18th century Ottoman poet Nev'îzâde Atâyî detailed same-sex relationships in his manuscript Hamse. Hamse included stories of individuals inside the Imperial Council, and discussed social values of the century, as well as moral and ethical codes. It features two young male characters who travel by sea to Egypt, before being captured and enslaved by European soldiers. While they are enslaved, the European kidnappers fall in love with their prisoners.[39] Such homoerotic imagery is also typical of hamse pentalogies, which featured erotic miniature paintings of sexual scenes.[40]

Homosexuality in the Ottoman Empire was not only between men. Although less visible than between men, sexuality between women has also been the subject of poetry. In the poems of female poets it is usually not clear whether the lover is a woman or a man. Mihri Hatun, a highly educated unmarried female poet, wrote a poem where she pretends to be a man in love with a woman. Some interpret this as expressing her own love for women.[41][42]

Western perceptions

In the West, homoerotic depictions of the Orient (including the Ottoman Empire) have been considered an aspect of literary Orientalism, which has made Western discussion on Islamic gender and sexual identity difficult.[43]

The English historian Edward Shepherd Creasy wrote in 1835 that "it became Turkish practice to procure by treaty, by purchase, by force or by fraud bands of the fairest children of the conquered Christians who were placed in the palaces of the Sultan, his viziers, and his pachas, under the title of pages, but too often really to serve as the helpless materials of abomination".[44] In 1913, Albert Howe Lybyer claimed that "the vice which takes its name from Sodom was very prevalent among the Ottomans, especially among those in high positions".[45]

While Western observers such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, denied that lesbian sexual activity occurred in the hammams (traditional gender-segregated public bathhouses);[46] other observers also made assertions of lesbian sexual practices in Ottoman seraglios, or harems.[47] This was in part due to Western perceptions of the Ottomans as being prone to sexual perversion, but was also borne from criticism of gender segregation in Ottoman society, with many aspects of same-sex activity being attributed to situational homosexuality.[48]

The Ottoman official Mehmet Cemaleddin Efendi was offered male prostitutes while on his stay in Paris between 1903 and 1906 by his hosts, who thought that being Turkish, he would be interested. This discomfited him, who later wrote that the streets of Paris had "1500 boys exclusively occupied in sodomy" with their availability and prices advertised on printed cards, which was far more blatant in France than anywhere in the Ottoman Empire.[46] This perception altered societal norms and attitudes (including the presentation of same-sex desire in literature) as the Ottoman Empire sought to become more Western.[48] With the Westernization of the Ottoman Empire, homosexuality began to be regarded in nineteenth-century Ottoman society as a deviant form of sexual expression.[31] It is also possible that some literary scenes of a homosexual nature were removed by censors at a later date, when heterosexuality became more normative in Ottoman society.[49]

In the West, Coleman Barks's versions of Rumi's works popularised his gazel literature. However, in recent years these versions have been criticised for their inaccuracy,[50] which had the effect of "reducing the divine to the sexual", according to translation and comparative literature experts Omid Azadibougar and Simon Patton, as well as ignoring cultural context in his versions of Rumi's work.[51] The translator Dick Davis also notes the difficulty in translating Persian language poetry into English due to the lack of gender pronouns in Persian.[33]

Homosexuality was discussed in the bāhnāmes ("part-medical, part-erotic treatises"), with a specific focus on male homosexuality, including those adopted by the scholar Mehmed Gazâlî, tailored for Prince Şehzade Korkut, the son of Sultan Bayezid II. The original composition, Alfiyya va Shalfiyya, was commissioned by the Seljuk Toghan-Shah is described by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall as a renowned "sotadic" work (referencing a geographic zone in which pederasty is allegedly prevalent and celebrated among the indigenous inhabitants).[52]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Katz 2009.

- ^ de Groot 2010.

- ^ a b c d Elif 2020.

- ^ a b c d Lapidus & Lena 2014.

- ^ Semerdjian 2008.

- As reviewed by Kern 2011, Sluglett 2009 and Russell 2010

- ^ Rowson 1991.

- ^ Alipour 2017.

- ^ Rowson 1991, pp. 675–676.

- ^ Murray & Roscoe 1997, pp. 305–310.

- ^ a b Arvas 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Kayaal 2020, p. 34.

- ^ Murray & Roscoe 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Murray & Roscoe 1997, p. 23-25.

- ^ de Vaudoncourt 1816, p. 278.

- ^ Murray 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Murray 2002, p. 60-61.

- ^ Beşiroğlu 2019, p. 6.

- ^ Beşiroğlu 2019.

- ^ Karayanni 2006, pp. 78, 82–83.

- ^ Beşiroğlu 2019, p. 9.

- ^ Murray & Roscoe 1997, p. 32.

- ^ a b Bouhdiba 2008, p. 167.

- ^ Hayes 2000, p. 206.

- ^ Pasin 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Germen 2015.

- ^ a b Ozsoy 2021.

- ^ Strachey Bucknill & Apisoghom S. Utidjian 1913.

- ^ a b c Zeevi, Dror. "Hiding Sexuality - Disappearance of Sexual Discourse in the Late Ottoman Middle East". Social Analysis.

- ^ Kreil, Sorbera & Tolino 2022, p. 91.

- ^ Schick 2018.

- ^ a b Arvas 2014, p. 145.

- ^ Murray & Roscoe 1997, p. 132–133.

- ^ a b c Mohr 2017.

- ^ Arvas 2014, pp. 149–154.

- ^ Schick 2004, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Starkey 2021, p. 264.

- ^ Murray & Roscoe 1997, pp. 22–23, 33–34.

- ^ Artan & Schick 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Erdman 2019.

- ^ Artan & Schick 2013, p. 157.

- ^ Arvas 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Havlioğlu 2010.

- ^ Boone 2014, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Dunne 1990, p. 72.

- ^ Quoted in Murray & Roscoe 1997, p. 176

- ^ a b Murray 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Murray 2007, p. 103.

- ^ a b Arvas 2014, p. 146.

- ^ Artan & Schick 2013, p. 187.

- ^ For further discussion, see: "Corrections of Popular Versions". www.dar-al-masnavi.org. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Azadibougar & Patton 2015, p. 177.

- ^ Artan & Schick 2013, pp. 157–8.

Bibliography

- Alipour, Mehrdad (2017). "Islamic shari'a law, neotraditionalist Muslim scholars and transgender sex-reassignment surgery: A case study of Ayatollah Khomeini's and Sheikh al-Tantawi's fatwas". International Journal of Transgenderism. 18 (1). Taylor & Francis: 91–103. doi:10.1080/15532739.2016.1250239. ISSN 1553-2739. LCCN 2004213389. OCLC 56795128. S2CID 152120329.

- Artan, Tülay; Schick, İrvin Cemil (2013). "Otomanizing pornotopia: Changing visual codes in eighteenth-century Otoman erotic miniatures". In Leoni, Francesca; Natif, Mika (eds.). Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 157–207. ISBN 978-1-4094-6438-9.

- Arvas, Abdulhamit (December 2014). "8". From the Pervert, Back to the Beloved: Homosexuality and Ottoman Literary History, 1453–1923. The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–159. ISBN 9781139547376.

- Azadibougar, Omid; Patton, Simon (2015). "Coleman Barks' Versions of Rumi in the USA". Translation and Literature. 24 (2): 172–189. doi:10.3366/tal.2015.0200. ISSN 0968-1361. JSTOR 24585407.

- Beşiroğlu, Şefika Şehvar (2019-03-17). "Music, Identity, Gender: Çengis, Köçeks, Çöçeks". ITU Turkish Music State Conservatory, Musicology Department. Academia.edu.

- Boone, Joseph A. (2014-03-25). The Homoerotics of Orientalism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52182-6.

- Bouhdiba, Abdelwahab (2008) [1975]. Sexuality in Islam. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781135030377.

- Dunne, Bruce W. (1990). "Homosexuality in the Middle East: An Agenda for Historical Research". Arab Studies Quarterly. 12 (3/4): 72. ISSN 0271-3519. JSTOR 41857885.

- Elif, Yılmazlı (Spring 2020). "Osmanlı'da HomoSosyal Mekânlar ve Cinsel Yönelimler" [Homosocial Places and Sexual Orientations In the Ottoman Empire] (PDF). Eğitim Bilim Toplum. 18 (70): 38–63. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- Erdman, Michael (June 13, 2019). "Same-Sex Relations in an 18th century Ottoman Manuscript". Asian and African studies blog. British Library. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Germen, Baran (March 1, 2015). "Of Parks and Hamams: Queer Heterotopias in the Age of Neoliberal Modernity and the Gay Citizen". Intersectional Perspectives: Identity, Culture, and Society. 5 (1): 111–137. doi:10.18573/ipics.76. ISSN 2752-3497. S2CID 242117795.

- de Groot, Alexander H. (11 August 2010). "6. The Historical Development of the Capitulatory Regime in the Ottoman Middle East from the Fifteenth to the Nineteenth Century". The Netherlands and Turkey. Gorgias Press. pp. 95–128. doi:10.31826/9781463226022-008. ISBN 9781463226022.

- Havlioğlu, Didem (1 May 2010). "On the margins and between the lines: Ottoman women poets from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries" (PDF). Turkish Historical Review. 1 (1): 25–54. doi:10.1163/187754610X494969. hdl:10161/10628.

- Hayes, Jarrod (2000). Queer Nations: Marginal Sexualities in the Maghreb. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-32105-9.

- Karayanni, Stavros Stavrou (2006). Dancing Fear & Desire: Race, Sexuality and Imperial Politics in Middle Eastern Dance. WLU Press. ISBN 088920926X.

- Katz, Stanley Nider (2009). Ottoman Empire: Islamic Law in Asia Minor (Turkey) and the Ottoman Empire - Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195134056. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- Kayaal, Tuğçe (2020). ""Twisted Desires," Boy-Lovers, and Male–Male Cross-Generational Sex in the Late Ottoman Empire (1912–1918)". Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques. 46: 31–46. doi:10.3167/hrrh.2020.460103. S2CID 226128832.

- Kreil, Aymon; Sorbera, Lucia; Tolino, Serena (30 June 2022). Sex and Desire in Muslim Cultures: Beyond Norms and Transgression from the Abbasids to the Present Day. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-7556-3713-3.

- Lapidus, Ira M.; Lena, Salaymeh (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). pp. 361–362. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Mohr, Melanie Christina (9 January 2017). "Homoerotic poetry in Islam: Reeling with desire". Qantara.de. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- Murray, Stephen O. (June 2002). Homosexualities. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-55195-1.

- Murray, Stephen O. (2007). "Homosexuality in The Ottoman Empire". Historical Reflections. 33 (1): 101–116.

- Murray, Stephen O.; Roscoe, Will (February 1, 1997). Islamic Homosexualities. New York University Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814761083.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-8147-6108-3.

- Ozsoy, Elif Ceylan (2021). "Decolonizing Decriminalization Analyses: Did the Ottomans Decriminalize Homosexuality in 1858?". Journal of Homosexuality. 68 (12): 1979–2002. doi:10.1080/00918369.2020.1715142. hdl:10871/120331. PMID 32069182. S2CID 211191107.

- Pasin, Burkay (2016). "A Critical Reading Of The Ottoman-Turkish Hammam As A Representational Space Of Sexuality". METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture. 33 (2).

- Rowson, Everett K. (October 1991). "The Effeminates of Early Medina" (PDF). Journal of the American Oriental Society. 111 (4). American Oriental Society: 671–693. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.1504. doi:10.2307/603399. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 603399. LCCN 12032032. OCLC 47785421. S2CID 163738149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008.

- Schick, İrvin Cemil (2004). "Representation of Gender and Sexuality in Ottoman and Turkish Erotic Literature". The Turkish Studies Association Journal. 28 (1/2): 81–103. ISSN 2380-2952. JSTOR 43383697.

- Schick, İrvin Cemil (March 23, 2018). "What Ottoman erotica teaches us about sexual pluralism". Aeon. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Semerdjian, Elyse (8 December 2008). "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-5155-0.

- Kern, Karen M. (February 2011). "Elyse Semerdjian, "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo, Gender, Culture, and Politics in the Middle East (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2008). Pp. 285. $29.95 cloth". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 43 (1): 158–160. doi:10.1017/S0020743810001364. ISSN 1471-6380. S2CID 153580187.

- Sluglett, Peter (2009). "Review of "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law and Community in Ottoman Aleppo". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 72 (3): 567–569. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09990127. ISSN 0041-977X. JSTOR 40379038.

- Russell, Mona L. (1 December 2010). ""Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo . By Elyse Semerdjian. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2008. Pp. xxxvii, 247. $29.95.)". The Historian. 72 (4): 914–915. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2010.00281_4.x. S2CID 143100931.

- Starkey, Paul (30 September 2021). Kellman, Steven G.; Lvovich, Natasha (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Literary Translingualism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-44151-2.

- Strachey Bucknill, John Alexander; Apisoghom S. Utidjian, Haig (1913). "The Imperial Ottoman Penal Code". The Turkish Text. Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, Amen Corner, London, E.C.

- de Vaudoncourt, Guillaume (1816). Memoirs on the Ionian Islands, Considered in a Commercial, Political, and Military, Point of View, ... Translated by William Walton. Cradock and Joy.

External links

- Lena Mattheis (7 February 2023). ""Queerness in the Ottoman Empire" with Tuğçe Kayaal". Queer Lit (Podcast).