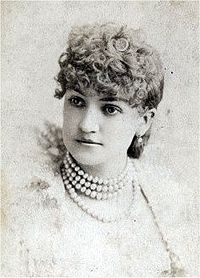

Kyrle Bellew

Kyrle Bellew | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Harold Kyrle Money Bellew 28 March 1850 Prescot, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 2 November 1911 (aged 61) Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S. |

| Resting place | Saint Raymond's Cemetery, The Bronx, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Harold Dominick Harold Higgin Harold Kyrle |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1871–1911 |

| Spouse | Eugenie Le Grand (m. 1873; div. 1888) |

| Signature | |

Harold Kyrle Money Bellew[1] (28 March 1850 – 2 November 1911) was an English stage and silent film actor. He notably toured with Cora Brown-Potter in the 1880s and 1890s, and was cast as the leading man in many stage productions alongside her. He was also a signwriter, gold prospector and rancher mainly in Australia.[2]

Early life

Bellew was born in Prescot, Lancashire, the son of Rev. John Chippendall Montesquieu Bellew and Eva Maria Bellew (née Money). His mother was a widow at the time of his parents' marriage on 27 March 1847.[3][4] She was the youngest daughter of Vice-Admiral Rowland Money, C.B., R.N., and Mary Ann Tombs.[5] She married her first husband Henry Edmund Michell Palmer, a soldier in the Indian Army, on 8 February 1843.[6] However, Palmer died of "hill fever" in Madras, India on 9 November 1846.[7]

His father was born John Chippendall Higgin in Lancashire on 3 August 1823[8] to Robert Higgin and Anne Maria Higgin (née Bellew). His lineage was called into question by the Reverend Samuel Gambier, who believed him to be a natural son of his friend and actor, William Macready, whom John Bellew did resemble and correspond with regularly until 1850. In 1844, he changed his name to his mother's maiden name while still a student at St Mary Hall, and he was ordained an Anglican priest in 1848. He was first appointed curate of St Andrew's in Worcester in 1848, and was transferred to Prescot, Lancashire, in 1850.[9]

On 17 November 1851, the Bellew family travelled to India on board the Hotspur and moved into a large house on Harrington Street in Calcutta.[10] John Bellew had been appointed as an assistant chaplain to St John's Cathedral in Calcutta, India.[8] Kyrle's parents separated in November 1853, after John Bellew discovered licentious correspondence between Eva and 23-year-old Ashley Eden, a civil servant with the East India Company.[11] John Bellew sued for divorce from Eva on 6 March 1855 on grounds of adultery. Eva counter-sued, claiming ill-treatment. John Bellew named Eden as his wife's lover and was granted a divorce on unequivocal grounds.[12] On 13 August 1861, Kyrle's mother married for a third time, to Ashley Eden[13] and she lived in India until her death on 10 January 1877.[5]

Meanwhile, John Bellew received custody of the children and left India in 1855. On their return to England, the family first settled in St Johns Wood where the John Bellew was assistant priest at St Philip's on Regent St. The family moved to Hamilton Terrace, Marylebone in 1857 after John Bellew was placed in charge of St Mark's.[8] John Bellew married Emily Louisa Wilkinson (née East) in Dublin, Ireland on 23 September 1861 and the Bellews resided at Bedford Chapel in Bloomsbury from 1862 to 1868.[8]

Kyrle Bellew's siblings were an older brother Evelyn Montesquieu Gambier (b. 25 October 1847)[14] who emigrated to the United States in the late 1860s, married Anita Killen and died childless on 1 December 1900.[15] An older sister Eva Sibyl Bellew (b. October 1848 in Worcester).[16] She married civil engineer John Hooper Wait in March 1873[17] and lived in Bhownuggur, India until her husband's suicide on 27 June 1876. At the time of the 1891 Census, she was living as a nun in the Poor Clares convent on Cornwall Street, Kensington; she died childless in 1927. His youngest sister, Ida Percy Clare (b. 17 June 1852 in Calcutta, India). [18] She married Joseph Boulderson, of the 68th Regiment, in 1874[19] and had two children, Ida Sybil Mary and Shadwell Joseph Boulderson, before dying in the first quarter of 1902.[20]

Kyrle Bellew was educated at the Lancaster Royal Grammar School and received lessons from private tutors, notably learning Latin along with Leslie Ward. However his home life was not happy because Kyrle Bellew did not get along with his new stepmother or stepsister, Maud Wilkinson. Kyrle Bellew described this tumultuous time in his life in his posthumous work Short Stories.[citation needed]

In the early 1860s he attempted to run away from home to the East India docks to start a life at sea, but he was ultimately returned home to his worried father. While John Bellew thought he should enter the ministry, the elder Bellew agreed to allow Kyrle Bellew to have a naval career. In 1866, Bellew was sent to train on HMS Conway, a famous training ship.[21] Conway was one of four training ships moored on the Mersey River that taught young boys how to be adept sailors, and it was specifically catered to developing officers for the Merchant Marines. Bellew spent two years on board the ship.[citation needed]

Career

With romantic profile and blond looks, Bellew was well suited for romances and melodramatic adventure stories of the day. In the 1880s and 90s he toured the world with a famous leading lady Mrs. Brown-Potter who was also known as Cora Brown Potter. They took Shakespearean and other classic plays from the United States to Australia. In Australia Bellew prior to being an actor was a reader, goldminer, and apparently bought a large amount of property.[22]

In 1888 Bellew began giving acting lessons to Mrs. Leslie Carter, a married socialite. In 1889, Bellew was named as a co-respondent in the highly publicised divorce case of Mrs. Leslie Carter. By the mid-1880s he was an actor of note and was considered a proper tutor for Caroline Dudley, Mrs. Carter's birth name. His preparing of Dudley for the stage required ample amounts of time with her and away from her husband. Eventually Mr. Carter became jealous and suspicious of the attention his wife was receiving, leading him to name Bellew and other men as his wife's lovers.[23]

In the last decade of his life, Bellew tended to his mining property in Australia, requiring making the long journeys back and forth to the United States. Finally at the turn of the century and in the US for good, he continued his popularity on Broadway premiering such plays as Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman to US audiences. He found time to venture into primitive motion pictures, which at the time were considered well beneath an actor of his stature; in 1905 he featured in Adventures of Sherlock Holmes; or, Held for Ransom. He died of pneumonia on 2 November 1911, in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he had been appearing in a play called The Mollusc.[24][25]

Personal life

Eugénie Marie Seraphié Le Grande[1][Note 1] was a French stage actress who was born and educated in Paris. She first appeared in the French vaudeville productions, Les Faux Bonshommes and Un Menage en Ville, and then moved on to Shakespearean theatre at Sadler's Wells Theatre in London before relocating to Australia.[21][26] Le Grande travelled to Melbourne via the passenger ship Lincolnshire from London on 4 December 1872 in the company of noted tragic actor Boothroyd Fairclough. She gave birth during the voyage on 15 January 1873 and arrived in Hobson's Bay on 20 February with an infant.[27]

Bellew married Le Grande on 27 October 1873 at St Patrick's Cathedral[28] under the name Harold Dominick Bellew. Bellew and Le Grande separated within a few weeks of marriage and did not live together again. One account of the brief marriage holds that Le Grande was previously the mistress of Boothroyd Fairclough. She secretly wed Bellew but returned to Fairclough when he discovered them on their honeymoon.[29] In Bellew's posthumous book, Short Stories, he relates a tale, attributed to a friend named Jack, that details the specifics of a sham marriage to a French actress. Several of the details in the story parallel known facts about Bellew and Le Grande, such as their marriage date[30] and the presence of an illegitimate child.[31] Bellew formally divorced Le Grande on 16 May 1888. After divorcing Bellew, Le Grande married Hector Alexander Wilson and continued to tour with acting companies in the United States, Britain and Canada. Hector Wilson died in January 1893 and left an estate in Australia valued at £ 27,000 to Eugénie.[citation needed][32] Bellew's obituaries identified him as "unmarried" and "survived by a sister", a nun with the Poor Clares in London,[33][25] and he left his entire estate- $3,642- to his friend Frank A. Connor, who as a young actor had been taken under Bellew's wing.[34] The actor Cosmo Kyrle Bellew- whose career began in 1914, three years after the death of Kyrle Bellew- claimed to be his son, which some sources repeat; others however remark the claim to be "uncertain".[35][1] Bellew, "unmarried" at his death, had been estranged from Le Grande following their wedding,[32] and the fate of Le Grande's previous child remains unknown. Cosmo Kyrle Bellew's birth date is often cited as 1885,[36] however, Cosmo Bellew's World War I draft registration card lists a birth date of 23 November 1874, with his nearest relative listed as Marjorie Bellew.[37]

Notes

- ^ Her last name has also been spelled Legrand and Le Grand.

References

- ^ a b c Mills, Julie. "Harold Kyrle Money Bellew (1850–1911)". Bellew, Harold Kyrle Money (1850–1911). Australian Dictionary of Biography Online. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Alexander Street Press Authorization". authorize.alexanderstreet.com.

- ^ Bengal (India). Supreme Court of Judicature (1856). Proceedings before the judges of the Supreme court of judicature at Calcutta, on Bellew's divorce (India) Bill: ordered to be printed 13th March 1856. p. 40.

- ^ "London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754–1921; Southwark; Southwark St Saviour; 1847; 10". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Marquis of Ruvigny & Raineval (1994). Plantagenet Roll of the Blood Royal: The Isabel of Essex Volume, Containing the Descendants of Isabel (Plantagenet), Countess of Essex. Genealogical Publishing Company. pp. 256–57. ISBN 9780806314341.

- ^ Le Follet: court magazine and museum. 1 June 1843. p. 69.

- ^ "Madras: miscellaneous". Allen's Indian Mail. 68: 10. 5 January 1847.

- ^ a b c d . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. pp. 192–193.

- ^ Gambier, James William (1906). Links in my life on land and sea. New York: E.P. Dutton and Company. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Staff. "Passengers arrived." Allen's Indian Mail, 3 January 1851: 10(188); pg. 10

- ^ Alexander, Alexander V. (16 January 1861). "Court For Divorce And Matrimonial Causes, 15 Jan." The Times. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "Bengal". Allen's Indian Mail. 13: 194. January–December 1855.

- ^ Lodge, Edmund, Anne Innes, Eliza Innes and Maria Innes (1869). The peerage and baronetage of the British empire as at present existing. Hurst and Blackett. p. 34.

eva maria money palmer.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robinson, Rev. Charles John (1883). A register of the scholars admitted into Merchant Taylor's School, from A.D. 1562 to 1874, Volume II. Lewes: Farncombe and Co. p. 336.

- ^ "New York City Deaths, 1892-1902; 21835". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "England & Wales, FreeBMD Birth Index, 1837–1915; 1848;Q4-Oct–Nov–Dec; B;117". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "FreeBMD. England & Wales, FreeBMD Marriage Index: 1837-1915 [database on-line]; 1873 > Q1-Jan-Feb-Mar > B > 8". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "England & Wales, Death Index: 1916-2005; 1927 > Q1-Jan-Feb-Mar > W > 3". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "FreeBMD. England & Wales, FreeBMD Marriage Index: 1837-1915 [database on-line]; 1874 > Q3-Jul-Aug-Sep > B > 10". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "FreeBMD. England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915 [database on-line], 2006; 1902 > Q1-Jan-Feb-Mar> B > 26". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b "The Theatre". May 1883: 312.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bellew. (1912) Short Stories pg. 5

- ^ Clinton, Craig (2006). Mrs. Leslie Carter: a biography of the early twentieth century American stage star. North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Publishers. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0-7864-2747-5.

- ^ Staff (2 November 1911). "KYRLE BELLEW IS CRITICALLY ILL;Actor Stricken with Pneumonia and Physicians Fear He Will Not Recover". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ a b Staff (3 November 1911). "KYRLE BELLEW IS DEAD.;Actor Expires of Pneumonia in Salt Lake City—Funeral to be Held Here". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "The following theatrical gossip appears in the Melbourne Age". Empire. 23 December 1872. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ "Shipping intelligence". The Argus. 21 February 1873. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Mills, Julie. "Harold Kyrle Money Bellew (1850–1911)". Bellew, Harold Kyrle Money (1850–1911). Australian Dictionary of Biography Online. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Topics of the day". Star. 15 January 1886. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Bellew (1912) Short Stories pg. 30

- ^ Bellew (1912). "pg. 32". Short Stories.

- ^ a b "26 May" (PDF). The New York Clipper. 26 May 1888. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ San Francisco Call, vol. 110, no. 156, 3 Nov. 1911, p. 3

- ^ "Kyrle Bellew's Estate", New York Times, Thursday, 26 September, 1912, p. 12- https://www.newspapers.com/clip/25607519/the-new-york-times/

- ^ Broadway Actors in Films, 1894-2015, Ron Liebman, MacFarland, Inc Publishers, 2017, p. 27

- ^ "John Gilbert in a new role not wholly romantic" (PDF). Dansville Breeze. 16 January 1928. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "National Archives and Records Administration World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918; Registration Location: New York County, New York; Roll: 1765975; Draft Board: 115". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)

Bibliography

- Bellew, Kyrle with Frank A. Connor (1912). Short Stories. New York: The Shakespeare Press.

- Short Stories (1912) on Wikisource