Pandour Corps

| Pandour Corps | |

|---|---|

| Korps Pandoeren | |

The uniform of a private of the Pandour Corps | |

| Active | 1793–1795 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Militia |

| Type | Light infantry |

| Role | Internal security |

| Size | 200 |

| Engagements | |

The Pandour Corps (Dutch: Korps Pandoeren) was a light infantry unit raised in the Dutch Cape Colony in 1793 during the French Revolutionary Wars. After the Dutch Republic became involved in the War of the First Coalition against France, the twin governors of the Cape Colony, Sebastiaan Cornelis Nederburgh and Simon Hendrik Frijkenius, raised the unit as an emergency measure to defend the colony against seaborne attack. The Pandour Corps consisted of Coloured soldiers, and was the second such unit raised in the colony after Dutch officials noted the effective skirmishing ability of Coloured troops compared to their European counterparts.

Coloured soldiers of the unit were mostly servants on burgher-owned farms, and many were recruited from Christian missions in the colony. In 1795, Great Britain launched an invasion of the Cape Colony in order to secure British trade with the East Indies. After British forces landed at the colony on 11 June, the Pandour Corps fought in several skirmishes, including successful attacks at Sandvlei on 8 August and Muysenburg on 1 September. However, dissatisfaction with their poor treatment led to a brief mutiny, which was resolved when Governor Abraham Josias Sluysken granted the mutineers several concessions. The Pandour Corps saw limited action afterward and was disbanded after Britain's takeover of the colony.

Although the Pandour Corps' existence was short-lived, the new British colonial authorities reconstituted the unit as the 300-strong Hottentot Corps in 1796, seeing the need to secure the loyalty of the Coloured community to Britain. The unit was renamed as the Cape Regiment in 1801, seeing action in the Third Xhosa War. Under the terms of 1802 Treaty of Amiens, the British returned the Cape Colony to the Dutch, which continued to raise Coloured units, including the Hottentot Light Infantry, which fought at the second British invasion of the Cape Colony. After assuming control of the colony for the second time, Britain continued to raised Coloured units, which would go on to serve in the fourth, fifth and sixth Xhosa wars.

Background

In 1652, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established a colony in Southern Africa which became known as the Cape Colony.[1] Settlers from Europe began emigrating to the colony, where they soon became involved in conflict with the indigenous Khoekhoe people. Along with the importation of thousands of slaves to the Cape Colony, this led to the need for a significant military presence in the colony for internal security duties.[2] However, the VOC's military, consisting largely of mercenaries, was unable to meet this need, and the burgher (free settler) population of the Cape Colony was too few in number. As a result, Dutch colonial officials turned to recruiting free people of colour (most of whom were manumitted slaves) for military service, most prominently for the colony's militia after it was established in 1722.[2]

Otto Frederick Mentzel, a German soldier stationed at the Cape Colony during the 1730s, noted in his memoirs that European troops in the colony were generally of poor quality. In his writings, Mentzel argued that instead of recruiting Europeans, the VOC should instead recruit local mixed-race people of Khoekhoe-European descent (known as Hottentots or Coloureds), describing them as "good marksmen and faithful".[2] Coloured people were already familiar with European forms of warfare, and suggestions to recruit them for military service was met with increasing approval among officials of the Cape Colony. During the 1770s, as Dutch expansion on the colony's frontier stalled due to resistance from the Khoekhoe and San peoples, VOC officials took a closer interest in the Coloured community. This resulted in the establishment of the Free Corps, a militia unit of Coloured troops raised in Stellenbosch.[2]

In 1780, the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War broke out between the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of Great Britain. After news of the war reached the Cape Colony, VOC officials in the colony formed the Bastard Hottentot Corps in 1781.[2][3] Based in Cape Town, the unit consisted of 400 men and was under the command of officers Hendrik Eksteen and Gerrit Munnik.[4] Unlike the Free Corps, the Bastard Hottentots Corps was not a segregated unit, consisting of both Coloured and White soldiers.[2] It was disbanded in 1782 when French mercenaries arrived at the Cape Colony, after seeing no action during fourteen months of service.[4]

Service

In 1793, after the Dutch Republic became involved in the War of the First Coalition of the French Revolutionary Wars, the twin governors of the Cape Colony Sebastiaan Cornelis Nederburgh and Simon Hendrik Frijkenius raised a light infantry unit of 200 men which was named the Pandour Corps (Dutch: Korps Pandoeren).[5][2] The unit, raised an emergency measure to defend the colony from a possible French attack, consisted largely of Coloured servants released from European-owned farms and supplied with equipment by their burgher masters; the Moravian mission at Baviaanskloof provided significant numbers of recruits for the unit.[6] South African academic Johan de Villiers argued that the decision to name the unit after the pandour troops of Eastern Europe was influenced by the military service of Austrian pandours in the Low Countries during the War of the Austrian Succession.[6] A segregated unit, the Pandour Corps' enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers consisted of Coloured recruits familiar with the use of muskets. Officers of the unit were drawn from experienced white personnel of the colony's garrison and militia units, and Captain Jan Cloete, a wealth burgher who owned land near Stellenbosch, was appointed as commandant of the Pandour Corps.[5][6]

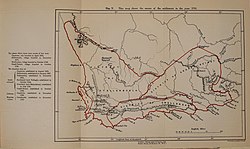

French troops overran the Dutch Republic in 1795, establishing the client Batavian Republic in its stead.[7] William V, Prince of Orange fled to England, where he issued the Kew Letters urging Dutch colonial officials to cooperate with British forces sent to occupy their colonies.[8] At the urging of Sir Francis Baring, Secretary of State for War Henry Dundas dispatched a British expeditionary force to invade the Cape Colony and eliminate the potential threat it posed to Britain's trade with the East Indies.[9] When the expeditionary force arrived at Simon's Bay on 11 June, the Pandour Corps was stationed at defensive fortifications constructed at the strategic location of Muysenburg alongside several other infantry and cavalry units under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Carel Matthys Willem de Lille.[6][10] The Dutch colonial government, hesitating to attack the British outright, stood by as they took control of a strategic bridgehead at a VOC outpost in Simon's Bay. Pandour Corps troops were subsequently involved in several skirmishes with the British, but a combined ground and naval offensive by the expeditionary force against Dutch forces at Muysenburg on 7 August resulted in the unit being withdrawn to Steenberg.[6][10]

On the very next day, the Pandour Corps and Swellendam Light Cavalry attacked the vanguard of the British expeditionary force at Sandvlei, forcing them to retreat while leaving their provisions and baggage behind.[10][11] Between five and six soldiers of the unit were killed, and "it was clear that members of this corps excelled in unconventional or guerilla warfare."[6] On the morning of 1 September, the Pandour Corps, again operating in concert with the Swellendam Light Cavalry, attacked two British outposts near Muysenburg, killing 5 soldiers and wounding 14 while suffering no casualties of their own. However, in the afternoon the unit mutinied by marching with their weapons drawn to the Castle of Good Hope to personally present their complaints of being ill-treated and poorly compensated to Governor Abraham Josias Sluysken. Sluysken managed to quell the mutiny by granting the unit several concessions and giving them each two farthings. On 2 September the Pandour Corps marched back to Steenberg, but played no further role in the invasion until Sluysken surrendered to the British on 14 September.[6][10]

Aftermath

The Pandour Corps was disbanded as a result of the British takeover.[5] However, the new British administration in the Cape Colony reconstituted the unit as the Hottentot Corps in May 1796.[12] This was done as the administration concluded that raised a Coloured unit was necessary to secure the loyalty of that community to Britain and intimidate rebellious burghers into accepting British rule; Villiers described the decision as "a frankly actuated more by political than military views."[13] British officials perceived the establishment of the Hottentot Corps as the best way to alter the lifestyle of the Coloured community, which were stereotyped as excessively sedentary by Dutch colonial accounts. Governor George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney remarked in 1797 that "The Hottentot is capable of a much greater degree of civilisation than is generally imagined, and perhaps converting him into a soldier may be one of the best steps towards it."[13] The unit consisted of 300 men and was stationed at Wynberg before moving to Hout Bay in 1798.[12]

On 25 June 1801, the Hottentot Corps was reorganised into the Cape Regiment, which was constituted as a 735-strong line infantry regiment of ten companies. It fought in the Third Xhosa War, and a number of the Cape Regiment's Coloured soldiers were given plots of land as reward for their military service.[14] In 1802, the British signed the Treaty of Amiens, with stipulated that they would return the Cape Colony to the Batavian Republic.[15][16] The Cape Regiment was disbanded, but the new Batavian authorities raised the Free Hottentot Corps on 21 February 1803. Batavian colonial officials compiled a list of all Coloureds in the Cape Colony to assist efforts to recruit Coloured soldiers for the unit. This unit was subsequently renamed as the Hottentot Light Infantry and fought at the Battle of Blaauwberg of the War of the Third Coalition, which saw another British expeditionary force invade and occupy the Cape Colony in January 1806.[14][11]

After establishing control over the Cape Colony, the British raised the Cape Regiment once again in October 1806. The unit continued to consist of ten companies with white officers and Coloured enlisted personnel, and Major John Graham was transferred from the 93rd Regiment of Foot to command the Cape Regiment, which fought in the Fourth Xhosa War. A troop of light cavalry was subsequently added to the unit, though on 24 September 1817 the troop and eight of the original ten infantry companies were disbanded. The two remaining companies were transformed into the Cape Cavalry, a unit of 100 dragoons, and the 100-strong Cape Light Infantry, both of which participated in the Fifth Xhosa War. In 1820 the two units were combined and renamed as the Cape Corps, which was subsequently reorganised into the Cape Mounted Riflemen on 25 November 1827.[17] The new unit's infantry wing was disbanded and the whole unit was transformed into a battalion-sized mounted infantry unit armed with carbines and equipped with dark green uniforms, seeing action in the Sixth Xhosa War.[3][18]

References

Footnotes

- ^ Welsh 2000, pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Malherbe 2002, pp. 94–99.

- ^ a b Richards 2008, p. 189.

- ^ a b Pretorius 2014, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Pretorius 2014, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g Villiers 2020, pp. 205–217.

- ^ Chandler 1999, p. 44.

- ^ Potgeiter & Grundlingh 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Potgeiter & Grundlingh 2007, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Malherbe 2002, pp. 95–99.

- ^ a b Steenkamp & Gordon 2005.

- ^ a b Pretorius 2014, p. 53.

- ^ a b Malherbe 2002, pp. 96–99.

- ^ a b Malherbe 2002, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Grainger 2004, p. 70.

- ^ Chandler 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Tylden 1938, p. 227.

- ^ Tylden 1938, pp. 227–231.

Bibliography

- Chandler, David (1999) [1993]. Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-203-4.

- Grainger, John D. (2004). The Amiens Truce: Britain and Bonaparte, 1801–1803. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-8438-3041-2.

- Malherbe, Vertrees C. (2002). "The Khoekhoe soldier at the Cape of Good Hope: How the Khoekhoen were drawn into the Dutch and British defensive systems, to c. 1809". Military History Journal. 12 (3). South African Military History Society.

- Pretorius, Fransjohan (2014). A History of South Africa: From the Distant Past to the Present Day. Protea Book House. ISBN 978-1-8691-9908-1.

- Potgeiter, Thean; Grundlingh, Arthur (2007). "Admiral Elphinstone and the Conquest and Defence of the Cape of Good Hope, 1795–96". Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies. 35 (2). Stellenbosch University.

- Richards, Jonathan (2008). The Secret War: A True History of Queensland's Native Police. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-3639-6.

- Steenkamp, Willem; Gordon, Antony (2005). "The Battle of Blaauwberg 200 Years Ago". Military History Journal. 13 (4). South African Military History Society.

- Tylden, G. (1938). "The Cape Mounted Riflemen, 1827-1870". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 17 (68). Society for Army Historical Research.

- Villiers, Johan de (2020). "The Pandour Corps, 1793-1795: Soldiers in defence of the Cape Colony towards the end of Dutch rule". Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe. 60. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe.

- Welsh, Frank (2000). A History of South Africa. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-0063-8421-2.