Koine Greek

| Koine Greek | |

|---|---|

| ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος | |

| Pronunciation | [(h)e̝ kyˈne̝ diˈalektos] |

| Region | Hellenistic Kingdoms and Roman Empire. By the Early Middle Ages, used in the Southern Balkans, Aegean Islands and Ionian Islands, Asia Minor, parts of Southern Italy and Sicily, Byzantine Crimea, the Levant, Egypt and Nubia |

| Ethnicity | Greeks |

| Era | 300 BC – 600 AD (Byzantine official use until 1453); developed into Medieval Greek, survives as the liturgical language of the Greek Orthodox and the Greek Catholic churches[1] |

Early forms | |

| Greek alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | grc |

| ISO 639-3 | (a proposal to use ecg was rejected in 2023[2]) |

grc-koi | |

| Glottolog | koin1234 |

Koine Greek[a] (ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinḕ diálektos, lit. 'the common dialect'),[b] also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-regional form of Greek spoken and written during the Hellenistic period, the Roman Empire and the early Byzantine Empire. It evolved from the spread of Greek following the conquests of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC, and served as the lingua franca of much of the Mediterranean region and the Middle East during the following centuries. It was based mainly on Attic and related Ionic speech forms, with various admixtures brought about through dialect levelling with other varieties.[6]

Koine Greek included styles ranging from conservative literary forms to the spoken vernaculars of the time.[7] As the dominant language of the Byzantine Empire, it developed further into Medieval Greek, which then turned into Modern Greek.[8]

Literary Koine was the medium of much post-classical Greek literary and scholarly writing, such as the works of Plutarch and Polybius.[6] Koine is also the language of the Septuagint (the 3rd century BC Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible), the Christian New Testament, and of most early Christian theological writing by the Church Fathers. In this context, Koine Greek is also known as "Biblical", "New Testament", "ecclesiastical", or "patristic" Greek.[9] The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote his private thoughts in Koine Greek in a work that is now known as Meditations.[10] Koine Greek continues to be used as the liturgical language of services in the Greek Orthodox Church and in some Greek Catholic churches.[11]

Name

The English-language name Koine is derived from the Koine Greek term ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος (hē koinḕ diálektos), meaning "the common dialect".[5] The Greek word κοινή (koinḗ) itself means "common". The word is pronounced /kɔɪˈneɪ/, /ˈkɔɪneɪ/, or /kiːˈniː/ in US English and /ˈkɔɪniː/ in UK English. The pronunciation of the word koine itself gradually changed from [koinéː] (close to the Classical Attic pronunciation [koi̯.nɛ̌ː]) to [cyˈni] (close to the Modern Greek [ciˈni]). In Modern Greek, the language is referred to as Ελληνιστική Κοινή, "Hellenistic Koiné", in the sense of "Hellenistic supraregional language").[12]

Ancient scholars used the term koine in several different senses. Scholars such as Apollonius Dyscolus (second century AD) and Aelius Herodianus (second century AD) maintained the term koine to refer to the Proto-Greek language, while others used it to refer to any vernacular form of Greek speech which differed somewhat from the literary language.[13]

When Koine Greek became a language of literature by the first century BC, some people distinguished two forms: written as the literary post-classical form (which should not be confused with Atticism), and vernacular as the day-to-day vernacular.[13] Others chose to refer to Koine as "the dialect of Alexandria" or "Alexandrian dialect" (ἡ Ἀλεξανδρέων διάλεκτος), or even the universal dialect of its time.[14] Modern classicists have often used the former sense.

Origins and history

- Dark blue: areas where Greek speakers probably were a majority

- Light blue: areas that were significantly Hellenized

Koine Greek arose as a common dialect within the armies of Alexander the Great.[13] Under the leadership of Macedon, their newly formed common variety was spoken from the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt to the Seleucid Empire of Mesopotamia.[13] It replaced existing ancient Greek dialects with an everyday form that people anywhere could understand.[15] Though elements of Koine Greek took shape in Classical Greece, the post-Classical period of Greek is defined as beginning with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, when cultures under Greek sway in turn began to influence the language.

The passage into the next period, known as Medieval Greek, is sometimes dated from the foundation of Constantinople by Constantine the Great in 330 AD, but often only from the end of late antiquity. The post-Classical period of Greek thus refers to the creation and evolution of Koine Greek throughout the entire Hellenistic and Roman eras of history until the start of the Middle Ages.[13]

The linguistic roots of the Common Greek dialect had been unclear since ancient times. During the Hellenistic period, most scholars thought of Koine as the result of the mixture of the four main Ancient Greek dialects, "ἡ ἐκ τῶν τεττάρων συνεστῶσα" (the composition of the Four). This view was supported in the early twentieth century by Paul Kretschmer in his book Die Entstehung der Koine (1901), while Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and Antoine Meillet, based on the intense Ionic elements of the Koine – σσ instead of ττ and ρσ instead of ρρ (θάλασσα – θάλαττα, 'sea'; ἀρσενικός – ἀρρενικός, 'potent, virile') – considered Koine to be a simplified form of Ionic.[13]

The view accepted by most scholars today was given by the Greek linguist Georgios Hatzidakis, who showed that despite the "composition of the Four", the "stable nucleus" of Koine Greek is Attic. In other words, Koine Greek can be regarded as Attic with the admixture of elements especially from Ionic, but also from other dialects. The degree of importance of the non-Attic linguistic elements on Koine can vary depending on the region of the Hellenistic world.[13]

In that respect, the varieties of Koine spoken in the Ionian colonies of Anatolia (e.g. Pontus, cf. Pontic Greek) would have more intense Ionic characteristics than others and those of Laconia and Cyprus would preserve some Doric and Arcadocypriot characteristics, respectively. The literary Koine of the Hellenistic age resembles Attic in such a degree that it is often mentioned as Common Attic.[13]

Sources

The first scholars who studied Koine, both in Alexandrian and Early Modern times, were classicists whose prototype had been the literary Attic Greek of the Classical period and frowned upon any other variety of Ancient Greek. Koine Greek was therefore considered a decayed form of Greek which was not worthy of attention.[13]

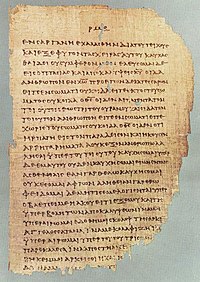

The reconsideration on the historical and linguistic importance of Koine Greek began only in the early 19th century, where renowned scholars conducted a series of studies on the evolution of Koine throughout the entire Hellenistic period and Roman Empire. The sources used on the studies of Koine have been numerous and of unequal reliability. The most significant ones are the inscriptions of the post-Classical periods and the papyri, for being two kinds of texts which have authentic content and can be studied directly.[13]

Other significant sources are the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible) and the Greek New Testament. The teaching of these texts was aimed at the most common people, and for that reason, they use the most popular language of the era.

Other sources can be based on random findings such as inscriptions on vases written by popular painters, mistakes made by Atticists due to their imperfect knowledge of Attic Greek or even some surviving Greco-Latin glossaries of the Roman period,[16] e.g.:

Καλήμερον, ἦλθες;

Bono die, venisti?

Good day, you came?Ἐὰν θέλεις, ἐλθὲ μεθ' ἡμῶν.

Si vis, veni mecum.

If you want, come with us.[c]Ποῦ;

Ubi?

Where?Πρὸς φίλον ἡμέτερον Λύκιον.

Ad amicum nostrum Lucium.

To our friend Lucius.Τί γὰρ ἔχει;

Quid enim habet?

Indeed, what does he have?

What is it with him?Ἀρρωστεῖ.

Aegrotat.

He's sick.

Finally, a very important source of information on the ancient Koine is the modern Greek language with all its dialects and its own Koine form, which have preserved some of the ancient language's oral linguistic details which the written tradition has lost. For example, Pontic and Cappadocian Greek preserved the ancient pronunciation of η as ε (νύφε, συνέλικος, τίμεσον, πεγάδι for standard Modern Greek νύφη, συνήλικος, τίμησον, πηγάδι etc.),[d] while the Tsakonian language preserved the long α instead of η (ἁμέρα, ἀστραπά, λίμνα, χοά etc.) and the other local characteristics of Doric Greek.[13]

Dialects from the southern part of the Greek-speaking regions (Dodecanese, Cyprus, etc.), preserve the pronunciation of the double similar consonants (ἄλ-λος, Ἑλ-λάδα, θάλασ-σα), while others pronounce in many words υ as ου or preserve ancient double forms (κρόμμυον – κρεμ-μυον, ράξ – ρώξ etc.). Linguistic phenomena like the above imply that those characteristics survived within Koine, which in turn had countless variations in the Greek-speaking world.[13]

Types

Biblical Koine

Biblical Koine refers to the varieties of Koine Greek used in Bible translations into Greek and related texts. Its main sources are:

- The Septuagint, a 3rd century BC Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and texts not included in the Hebrew Bible;

- The Greek New Testament, composed originally in Greek.

Septuagint Greek

There has been some debate to what degree Biblical Greek represents the mainstream of contemporary spoken Koine and to what extent it contains specifically Semitic substratum features. These could have been induced either through the practice of translating closely from Biblical Hebrew or Aramaic originals, or through the influence of the regional non-standard Greek spoken by originally Aramaic-speaking Hellenized Jews.

Some of the features discussed in this context are the Septuagint's normative absence of the particles μέν and δέ, and the use of ἐγένετο to denote "it came to pass". Some features of Biblical Greek which are thought to have originally been non-standard elements eventually found their way into the main of the Greek language.

H. St. J. Thackeray, in A Grammar of the Old Testament in Greek According to the Septuagint (1909), wrote that only the five books of the Pentateuch, parts of the Book of Joshua and the Book of Isaiah may be considered "good Koine". One issue debated by scholars is whether and how much the translation of the Pentateuch influenced the rest of the Septuagint, including the translation of Isaiah.[17]

Another point that scholars have debated is the use of ἐκκλησία ekklēsía as a translation for the Hebrew קָהָל qāhāl. Old Testament scholar James Barr has been critical of etymological arguments that ekklēsía refers to "the community called by God to constitute his People". Kyriakoula Papademetriou explains:

He maintains that ἐκκλησία is merely used for designating the notion of meeting and gathering of men, without any particular character. Therefore, etymologizing this word could be needless, or even misleading, when it could guide to false meanings, for example that ἐκκλησία is a name used for the people of God, Israel.[18]

New Testament Greek

The authors of the New Testament follow the Septuagint translations for over half their quotations from the Old Testament.[19]

The "historical present" tense is a term used for present tense verbs that are used in some narrative sections of the New Testament to describe events that are in the past with respect to the speaker. This is seen more in works attributed to Mark and John than Luke.[20] It is used 151 times in the Gospel of Mark in passages where a reader might expect a past tense verb. Scholars have presented various explanations for this; in the early 20th century some scholars argued that the use of the historical present tense in Mark was due to the influence of Aramaic, but this theory fell out of favor in the 1960s. Another group of scholars believed the historical present tense was used to heighten the dramatic effect, and this interpretation was favored in the New American Bible translation. In Volume II of the 1929 edition of A Grammar of the New Testament, W.F. Howard argues that the heavy use of the historical present in Herodotus and Thucydides, compared with the relatively infrequent usage by Polybius and Xenophon was evidence that heavy use of this verb tense is a feature of vernacular Koine, but other scholars have argued that the historical present can be a literary form to "denote semantic shifts to more prominent material."[21][22]

Patristic Greek

The term patristic Greek is sometimes used for the Greek written by the Greek Church Fathers, the Early Christian theologians in late antiquity. Christian writers in the earliest time tended to use a simple register of Koiné, relatively close to the spoken language of their time, following the model of the Bible. After the 4th century, when Christianity became the state church of the Roman Empire, more learned registers of Koiné also came to be used.[23]

Differences between Attic and Koine Greek

Koine period Greek differs from Classical Greek in many ways: grammar, word formation, vocabulary and phonology (sound system).[24]

Differences in grammar

Phonology

During the period generally designated as Koine Greek, a great deal of phonological change occurred. At the start of the period, the pronunciation was virtually identical to Ancient Greek phonology, whereas in the end, it had much more in common with Modern Greek phonology.

The three most significant changes were the loss of vowel length distinction, the replacement of the pitch accent system by a stress accent system, and the monophthongization of several diphthongs:

- The ancient distinction between long and short vowels was gradually lost, and from the second century BC all vowels were isochronic (having equal length).[13]

- From the second century BC, the Ancient Greek pitch accent was replaced with a stress accent.[13]

- Psilosis: loss of rough breathing, /h/. Rough breathing had already been lost in the Ionic Greek varieties of Anatolia and the Aeolic Greek of Lesbos.[13]

- The diphthongs ᾱͅ, ῃ, ῳ /aːi eːi oːi/ were respectively simplified to the long vowels ᾱ, η, ω /aː eː oː/.[13]

- The diphthongs αι, ει, and οι became monophthongs. αι, which had already been pronounced as /ɛː/ by the Boeotians since the 4th century BC and written η (e.g. πῆς, χῆρε, μέμφομη), became in Koine, too, first a long vowel /ɛː/ and then, with the loss of distinctive vowel length and openness distinction /e/, merging with ε. The diphthong ει had already merged with ι in the 5th century BC in Argos, and by the 4th century BC in Corinth (e.g. ΛΕΓΙΣ), and it acquired this pronunciation also in Koine. The diphthong οι fronted to /y/, merging with υ. The diphthong υι came to be pronounced [yj], but eventually lost its final element and also merged with υ.[25] The diphthong ου had been already raised to /u/ in the 6th century BC, and remains so in Modern Greek.[13]

- The diphthongs αυ and ευ came to be pronounced [av ev] (via [aβ eβ]), but are partly assimilated to [af ef] before the voiceless consonants θ, κ, ξ, π, σ, τ, φ, χ, and ψ.[13]

- Simple vowels mostly preserved their ancient pronunciations. η /e/ (classically pronounced /ɛː/) was raised and merged with ι. In the 10th century AD, υ/οι /y/ unrounded to merge with ι. These changes are known as iotacism.[13]

- The consonants also preserved their ancient pronunciations to a great extent, except β, γ, δ, φ, θ, χ and ζ. Β, Γ, Δ, which were originally pronounced /b ɡ d/, became the fricatives /v/ (via [β]), /ɣ/, /ð/, which they still are today, except when preceded by a nasal consonant (μ, ν); in that case, they retain their ancient pronunciations (e.g. γαμβρός > γαμπρός [ɣamˈbros], ἄνδρας > άντρας [ˈandras], ἄγγελος > άγγελος [ˈaŋɟelos]). The latter three (Φ, Θ, Χ), which were initially pronounced as aspirates (/pʰ tʰ kʰ/ respectively), developed into the fricatives /f/ (via [ɸ]), /θ/, and /x/. Finally ζ, which is still metrically categorised as a double consonant with ξ and ψ because it may have initially been pronounced as σδ [zd] or δσ [dz], later acquired its modern-day value of /z/.[13]

New Testament Greek phonology

The Koine-period Greek in the table is taken from a reconstruction by Benjamin Kantor of New Testament Judeo-Palestinian Koine Greek. The realizations of most phonemes reflect general changes around the Greek-speaking world, including vowel isochrony and monophthongization, but certain sound values differ from other Koine varieties such as Attic, Egyptian and Anatolian.[26]

More general Koine phonological developments include the spirantization of Γ, with palatal allophone before front-vowels and a plosive allophone after nasals, and β. [27] φ, θ and χ still preserve their ancient aspirated plosive values, while the unaspirated stops π, τ, κ have perhaps begun to develop voiced allophones after nasals.[28] Initial aspiration has also likely become an optional sound for many speakers of the popular variety.[29][e] Monophthongization (including the initial stage in the fortition of the second element in the αυ/ευ diphthongs) and the loss of vowel-timing distinctions are carried through. On the other hand, Kantor argues for certain vowel qualities differing from the rest of the Koine in the Judean dialect. Although it is impossible to know the exact realizations of vowels, it is tentatively argued that the mid-vowels ε/αι and η had a more open pronunciation than other Koine dialects, distinguished as open-mid /ɛ/ vs. close-mid /e/,[30] rather than as true-mid /e̞/ vs. close-mid /e̝/ as has been suggested for other varieties such as Egyptian.[31] This is evidenced on the basis of Hebrew transcriptions of ε with pataḥ/qamets /a/ and not tsere/segol /e/. Additionally, it is posited that α perhaps had a back vowel pronunciation as /ɑ/, dragged backwards due to the opening of ε. Influence of the Aramaic substrate could have also caused confusion between α and ο, providing further evidence for the back vowel realization.[32]

| letter | Greek | transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | α | a | /ɑ/ |

| Beta | β | b | /b/ ([b, β]) |

| Gamma | γ | g | /ɣ/ ([ɣ, g, ʝ]) |

| Delta | δ | d | /d/ |

| Epsilon | ε | e | /ɛ/ |

| Zeta | ζ | z | /z/ |

| Eta | η | ē | /e/ |

| Theta | θ | th | /tʰ/ |

| Iota | ι | i | /i/ |

| Kappa | κ | k | /k/ ([k, g]) |

| Lambda | λ | l | /l/ ([ʎ](?) |

| Mu | μ | m | /m/ |

| Nu | ν | n | /n/ ([n, m]) |

| Xi | ξ | x | /ks/ |

| Omicron | ο | o | /o̞/ |

| Pi | π | p | /p/ ([p, b]) |

| Rho | ρ | r | /r/ |

| Sigma | σ (-σ-/-σσ-) | s (-s-/-ss-) | /s/ ([s, z]) |

| Tau | τ | t | /t/ ([t, d]) |

| Upsilon | υ | y | /y/ |

| Phi | φ | ph | /pʰ/ |

| Chi | χ | ch | /kʰ/ |

| Psi | ψ | ps | /ps/ |

| Omega | ω | ō | /o/ |

| . | αι | ai | /ɛ/ |

| . | ει | ei | /i/ |

| . | οι | oi | /y/ |

| . | υι | yi | /yi/ (or /y/) |

| . | αυ | au | [ɑɸ(ʷ), ɑβ(ʷ)] |

| . | ευ | eu | [ɛɸ(ʷ), ɛβ(ʷ)] |

| . | ου | ou | /u/ |

| . | αι (ᾳ) | āi | /ɑ/ |

| . | ηι (ῃ) | ēi | /i/ |

| . | ωι (ῳ) | ōi | /o/ |

| . | ῾ | h | (/h/) |

Sample Koine texts

The following texts show differences from Attic Greek in all aspects – grammar, morphology, vocabulary and can be inferred to show differences in phonology.

The following comments illustrate the phonological development within the period of Koine. The phonetic transcriptions are tentative and are intended to illustrate two different stages in the reconstructed development, an early conservative variety still relatively close to Classical Attic, and a somewhat later, more progressive variety approaching Modern Greek in some respects.

Sample 1 – A Roman decree

The following excerpt, from a decree of the Roman Senate to the town of Thisbae in Boeotia in 170 BC, is rendered in a reconstructed pronunciation representing a hypothetical conservative variety of mainland Greek Koiné in the early Roman period.[33] The transcription shows raising of η to /eː/, partial (pre-consonantal/word-final) raising of ῃ and ει to /iː/, retention of pitch accent, and retention of word-initial /h/ (the rough breathing).

περὶ

peri

ὧν

hoːn

Θισ[β]εῖς

tʰizbîːs

λόγους

lóɡuːs

ἐποιήσαντο·

epojéːsanto;

περὶ

peri

τῶν

toːn

καθ᾿

katʰ

αὑ[τ]οὺς

hautùːs

πραγμάτων,

praːɡmátoːn,

οἵτινες

hoítines

ἐν

en

τῇ

tiː

φιλίᾳ

pʰilíaːi

τῇ

tiː

ἡμετέρᾳ

heːmetéraːi

ἐνέμειναν,

enémiːnan,

ὅπως

hópoːs

αὐτοῖς

autois

δοθῶσιν

dotʰôːsin

[ο]ἷς

hois

τὰ

ta

καθ᾿

katʰ

αὑτοὺς

hautùːs

πράγματα

práːɡmata

ἐξηγήσωνται,

ekseːɡéːsoːntai,

περὶ

peri

τούτου

túːtuː

τοῦ

tuː

πράγματος

práːɡmatos

οὕτως

húːtoːs

ἔδοξεν·

édoksen;

ὅπως

hópoːs

Κόιντος

ˈkʷintos

Μαίνιος

ˈmainios

στρατηγὸς

strateːɡòs

τῶν

toːn

ἐκ

ek

τῆς

teːs

συνκλήτου

syŋkléːtuː

[π]έντε

pénte

ἀποτάξῃ

apotáksiː,

οἳ

hoi

ἂν

an

αὐτῷ

autoːi

ἐκ

ek

τῶν

toːn

δημοσίων

deːmosíoːn

πρα[γμ]άτων

praːɡmátoːn

καὶ

kai

τῆς

teːs

ἰδίας

idíaːs

πίστεως

písteoːs

φαίνωνται.

pʰaínoːntai

Concerning those matters about which the citizens of Thisbae made representations. Concerning their own affairs: the following decision was taken concerning the proposal that those who remained true to our friendship should be given the facilities to conduct their own affairs; that our praetor/governor Quintus Maenius should delegate five members of the senate who seemed to him appropriate in the light of their public actions and individual good faith.

Sample 2 – Greek New Testament

The following excerpt, the beginning of the Gospel of John, is rendered in a reconstructed pronunciation representing a progressive popular variety of Koiné in the early Christian era.[34] Modernizing features include the loss of vowel length distinction, monophthongization, transition to stress accent, and raising of η to /i/. Also seen here are the bilabial fricative pronunciation of diphthongs αυ and ευ, loss of initial /h/, fricative values for β and γ, and partial post-nasal voicing of voiceless stops.

Ἐν

ˈen

ἀρχῇ

arˈkʰi

ἦν

in

ὁ

o

λόγος,

ˈloɣos,

καὶ

ke

ὁ

o

λόγος

ˈloɣos

ἦν

im

πρὸς

bros

τὸν

to(n)

θεόν,

tʰeˈo(n),

καὶ

ke

θεὸς

tʰeˈos

ἦν

in

ὁ

o

λόγος.

ˈloɣos.

οὗτος

ˈutos

ἦν

in

ἐν

en

ἀρχῇ

arˈkʰi

πρὸς

pros

τὸν

to(n)

θεόν.

tʰeˈo(n).

πάντα

ˈpanda

δι᾽

di

αὐτοῦ

aɸˈtu

ἐγένετο,

eˈʝeneto,

καὶ

ke

χωρὶς

kʰoˈris

αὐτοῦ

aɸˈtu

ἐγένετο

eˈʝeneto

οὐδὲ

ude

ἕν

ˈen

ὃ

o

γέγονεν.

ˈʝeɣonen.

ἐν

en

αὐτῷ

aɸˈto

ζωὴ

zoˈi

ἦν,

in,

καὶ

ke

ἡ

i

ζωὴ

zoˈi

ἦν

in

τὸ

to

φῶς

pʰos

τῶν

ton

ἀνθρώπων.

anˈtʰropon;

καὶ

ke

τὸ

to

φῶς

pʰos

ἐν

en

τῇ

di

σκοτίᾳ

skoˈtia

φαίνει,

ˈpʰeni,

καὶ

ke

ἡ

i

σκοτία

skoˈti(a)

αὐτὸ

a(ɸ)ˈto

οὐ

u

κατέλαβεν.

kaˈtelaβen

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made by Him; and without Him was not anything made that was made. In Him was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shines in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.

References

Notes

- ^ Pronunciation: UK: /ˈkɔɪni/ KOY-nee,[3] US: /ˈkɔɪneɪ/ KOY-nay or /kɔɪˈneɪ/ koy-NAY.[4][5]

- ^ Pronunciation: [(h)e̝ kyˈne̝ diˈalektos], later [i cyˈni ðiˈalektos].

- ^ The Latin gloss in the source erroneously has "with me", while the Greek means "with us".

- ^ On the other hand, not all scholars agree that the Pontic pronunciation of η as ε is an archaism. Apart from the improbability that the sound change /ɛː/>/e̝(ː)/>/i/ did not occur in this important region of the Roman Empire, Horrocks notes that ε can be written in certain contexts for any letter or digraph representing /i/ in other dialects–e.g. ι, ει, οι, or υ, which were never pronounced /ɛː/ in Ancient Greek–not just η (c.f. όνερον, κοδέσπενα, λεχάρι for standard όνειρο, οικοδέσποινα, λυχάρι.) He therefore attributes this feature of East Greek to vowel weakening, paralleling the omission of unstressed vowels. Horrocks (2010: 400)

- ^ For convenience, the rough breathing mark represents /h/, even if it was not commonly used in contemporary orthography. Parentheses denote the loss of the sound.

Citations

- ^ Demetrios J. Constantelos, The Greek Orthodox Church: faith, history, and practice, Seabury Press, 1967

- ^ "Change Request Documentation: 2009-060". SIL International. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Koine". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins. Retrieved 2014-09-24.

- ^ "Koine". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ a b "Koine". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b Bubenik, V. (2007). "The rise of Koiné". In A. F. Christidis (ed.). A history of Ancient Greek: from the beginnings to late antiquity. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 342–345.

- ^ Horrocks, Geoffrey (1997). "4–6". Greek: a history of the language and its speakers. London: Longman.

- ^ Horrocks, Geoffrey (2009). Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers. Wiley. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1-4443-1892-0.

- ^ Chritē, Maria; Arapopoulou, Maria (11 January 2007). A history of ancient Greek. Thessaloniki, Greece: Center for the Greek Language. p. 436. ISBN 978-0-521-83307-3.

- ^ "Maintenance". www.stoictherapy.com.

- ^ Makrides, Vasilios N; Roudometof, Victor (2013). Orthodox Christianity in 21st Century Greece: The Role of Religion in Culture, Ethnicity and Politics. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4094-8075-4. "A proposal to introduce Modern Greek into the Divine Liturgy was rejected in 2002"

- ^ Κοπιδάκης, Μ.Ζ. (1999). Ελληνιστική Κοινή, Εισαγωγή [Hellenistic Koine, Introduction]. Ιστορία της Ελληνικής Γλώσσας [History of the Greek Language] (in Greek). Athens: Ελληνικό Λογοτεχνικό και Ιστορικό Αρχείο. pp. 88–93.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Andriotis, Nikolaos P. History of the Greek Language.[page needed]

- ^ Gilbert, R (1823). "The British Critic, and Quarterly Theological Review". St. John's Square, Clerkenwell: University of California at Los Angeles. p. 338.

- ^ Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: W.W. Norton& Company Inc. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- ^ Augsburg.

- ^ Vergari, Romina (2015-01-12). "Aspects of Polysemy in Biblical Greek: the Semantic Micro-Structure of Kρισις". In Eberhard Bons; Jan Joosten; Regine Hunziker-Rodewald (eds.). Biblical Lexicology: Hebrew and Greek. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-031216-4. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ Papademetriou, Kyriakoula (2015-01-12). "The dynamic semantic role of etymology in the meaning of Greek biblical words. The case of the word ἐκκλησία". In Eberhard Bons; Jan Joosten; Regine Hunziker-Rodewald (eds.). Biblical Lexicology: Hebrew and Greek. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-031216-4. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ Evans, Craig A.; Tov, Emanuel (2008-10-01). "Introduction". Exploring the Origins of the Bible (Acadia Studies in Bible and Theology): Canon Formation in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-58558-814-5.

- ^ Porter, Stanley E.; Pitts, Andrew (2013-02-21). "Markan Idiolect in the Study of the Greek New Testament". The Language of the New Testament: Context, History, and Development. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-23477-2.

- ^ Osburn, Carroll D. (1983). "The Historical Present in Mark as a Text-Critical Criterion". Biblica. 64 (4): 486–500. JSTOR 42707093.

- ^ Strickland, Michael; Young, David M. (2017-11-15). The Rhetoric of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-3847-4.

- ^ Horrocks (1997: ch.5.11.)

- ^ A concise survey of the major differences between Attic and Koine Greek can be found in Reece, Steve, "Teaching Koine Greek in a Classics Department", Classical Journal 93.4 (1998) 417–429.

- ^ Horrocks (2010: 162)

- ^ Kantor 2023:345,764

- ^ Gignac, Francis T. (1970). "The Pronunciation of Greek Stops in the Papyri". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 101: 185–202. doi:10.2307/2936047. JSTOR 2936047.

- ^ Horrocks (2010): 111, 170–1

- ^ Horrocks (2010): 171, 179.

- ^ Kantor 2023:613

- ^ In example, c.f. Horrocks (2010), 167.

- ^ Kantor 2023:613

- ^ G. Horrocks (1997), Greek: A history of the language and its speakers, p. 87, cf. also pp. 105–109.

- ^ Horrocks (1997: 94).

Bibliography

- Abel, F.-M. Grammaire du grec biblique.

- Allen, W. Sidney, Vox Graeca: a guide to the pronunciation of classical Greek – 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-521-33555-8

- Andriotis, Nikolaos P. History of the Greek Language

- Buth, Randall, Ἡ κοινὴ προφορά: Koine Greek of Early Roman Period

- Bruce, Frederick F. The Books and the Parchments: Some Chapters on the Transmission of the Bible. 3rd ed. Westwood, NJ: Revell, 1963. Chapters 2 and 5.

- Conybeare, F.C. and Stock, St. George. Grammar of Septuagint Greek: With Selected Readings, Vocabularies, and Updated Indexes.

- Horrocks, Geoffrey C. (2010). Greek: A history of the language and its speakers (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Weir, Herbert (1956), Greek Grammar, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-36250-5

- Kantor, Benjamin (2023), he Pronunciation of New Testament Greek Judeo-Palestinian Greek Phonology and Orthography from Alexander to Islam, Eerdmans, ISBN 9780802878311.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1956), Greek Grammar, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-36250-5.

Further reading

- Bakker, Egbert J., ed. 2010. A companion to the Ancient Greek language. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Blass, Friedrich, and Albert Debrunner. 1961. Greek grammar of the New Testament and other early Christian literature. Translated and revised by R. W. Funk. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Christidis, Anastasios-Phoivos, ed. 2007. A history of Ancient Greek: From the beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Colvin, Stephen C. 2007. A historical Greek reader: Mycenaean to the koiné. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Easterling, P. E., and Carol Handley. 2001. Greek Scripts: An Illustrated Introduction. London: Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies.

- Evans, T. V., and Dirk Obbink, eds. 2009. The language of the papyri. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Gignac, Francis T. 1976–1981. A grammar of the Greek papyri of the Roman and Byzantine periods. 2 vols. Milan: Cisalpino-La Goliardica.

- Palmer, Leonard R. 1980. The Greek language. London: Faber & Faber.

- Stevens, Gerald L. 2009. New Testament Greek Intermediate: From Morphology to Translation. Cambridge, UK: Lutterworth Press.

- ––––. 2009. New Testament Greek Primer. Cambridge, UK: Lutterworth Press.

External links

- New Testament Greek Online by Winfred P. Lehmann and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Free Koine Greek Keyboard – A unicode keyboard originally developed by Char Matejovsky for use by Westar Institute scholars

- The Biblical Greek Forum – An online community for Biblical Greek

- Greek-Language.com – Dictionaries, manuscripts of the Greek New Testament, and tools for applying linguistics to the study of Hellenistic Greek

- Diglot A daily di-glot or tri-glot (Vulgate) reading