Stefan Milutin

Stefan Uroš II Milutin Стефан Урош II Милутин | |

|---|---|

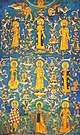

King Milutin, founder's portrait (fresco) in King's Church of the Studenica Monastery, painted during his lifetime, around 1314 | |

| Milutin the Ktetor | |

| Born | 1253 |

| Died | 29 October 1321 (aged 68) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| King of all Serbian and Maritime lands | |

| Reign | 1282–1321 |

| Coronation | 1282 |

| Predecessor | Stefan Dragutin |

| Successor | Stefan Dečanski |

| Born | Uroš II Milutin Nemanjić |

| Burial | St. Nedelya Cathedral in Sofia (relocated in 1460) |

| Spouse | Jelena Helena Doukaina Angelina Elizabeth of Hungary Anna Terter of Bulgaria Simonis Palaiologina |

| Issue | Stefan Konstantin Stefan Uroš III Dečanski |

| House | Nemanjić dynasty |

| Father | Stefan Uroš I |

| Mother | Helen of Anjou |

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox |

| Signature |  |

Stefan Uroš II Milutin (Serbian Cyrillic: Стефан Урош II Милутин, romanized: Stefan Uroš II Milutin; c. 1253 – 29 October 1321), known as Saint King, was the King of Serbia between 1282–1321, a member of the Nemanjić dynasty. He was one of the most powerful rulers of Serbia in the Middle Ages and one of the most prominent European monarchs of his time. Milutin is credited with strongly resisting the efforts of Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos to impose Roman Catholicism on the Balkans after the Union of Lyons in 1274. During his reign, Serbian economic power grew rapidly, mostly due to the development of mining. He founded Novo Brdo, which became an internationally important silver mining site. As most of the Nemanjić monarchs, he was proclaimed a saint by the Serbian Orthodox Church with a feast day on October 30.[1][2][3][4]

Early life

He was the youngest son of King Stefan Uroš I and his wife, Helen of Anjou. Unexpectedly he became king of Serbia after the abdication of his brother Stefan Dragutin. He was around 29. Immediately upon his accession to the throne he attacked Byzantine lands in Macedonia. In 1282, he conquered the northern parts of Macedonia including the city of Skoplje, which became his capital. Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos began preparations for war but he died before their completion. The next year Milutin advanced with his brother deep into Byzantine territory all the way to Kavala.

In 1284, Milutin also gained control of northern Albania and the city of Dyrrachion (Durrës). For the next 15 years there were no changes in the war. Peace was concluded in 1299 when Milutin kept the conquered lands as the dowry of Simonis, daughter of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos who became his fourth wife. In Nerodimlje župa Milutin had three courts, in Nerodimlje (protected by Petrič), Svrčin and Pauni.[5]

Wars with the Bulgarians and Mongols

At the end of the 13th century Bulgarian feudal lords Darman and Kudelin were jointly ruling the region of Braničevo (in modern Serbia) as independent or semi-independent lords. They regularly attacked Stefan Dragutin's Syrmian Kingdom, in Mačva, an area previously under the sovereignty of Elizabeth of Hungary. The Hungarian queen had sent troops to claim Braničevo in 1282–1284, but her forces had been repelled and her vassal lands plundered in retaliation.

Another campaign, this time organized by both Dragutin and Elizabeth, failed to conquer Darman and Kudelin's domains in 1285 and suffered another counter-raid by the brothers. It was not until 1291 when a joint force of Dragutin and the Serbian King Stefan Milutin managed to defeat the brothers and, for the first time ever, the region came under the rule of a Serb, as it was annexed by Dragutin. Responding to Dragutin's annexation of Braničevo the Bulgarian prince named Shishman that came to rule the semi-independent principality of Vidin around 1280, began to attack the Serbian domains to his west.

Shishman was a vassal of Nogai Khan, Khan of the Golden Horde and sought to expand his territories to the west, invading Serbia coming as far as Hvosno, the Bulgarians failed to capture Zdrelo (near Peć) and were pursued back to Vidin by the Serbs. Milutin devastated Vidin and the rest of Shishman's dominion, making Shishman take refuge on the other side of the Danube. The two however became allies after Milutin married Serbian župan Dragoš to the daughter of Shishman, later Milutin would give his daughter Neda (with title Anna) to Shishman's son Michael who would become the Tsar of Bulgaria in 1323.

Milutin and Nogai Khan would soon come into conflict because of the war with the Tsardom of Vidin. Nogai launched a campaign against Serbia but Milutin offered peace sending his son Stefan Dečanski to Nogai's court. Stefan stayed with his entourage there until 1296 or Nogai Khan's death in 1299.

Feud of the brothers

Disputes began between Milutin and his brother Stefan Dragutin after a peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire was signed in 1299. Dragutin in the meantime held lands from Braničevo in the east to the Bosna river in the west. His capital was Belgrade. War broke out between the brothers and lasted, with sporadic cease-fires, until Dragutin's death in 1314. By 1309, Milutin appointed his son, future king Stefan Dečanski, as governor of Zeta.[6] This meant that Stefan Dečanski was to be heir to the throne in Serbia and not Dragutin's son Stefan Vladislav II.[7] In order to gain an edge in his feud with Dragutin, Milutin sought support from the Papal States, even offering to convert himself and Serbs collectivly to Catholicism.[8]

Battles and supreme leadership

He captured Durrës in 1296.[9] The Battle of Gallipoli (1312) was fought by Serbian troops sent by Stefan Milutin to aid Byzantine Emperor Andronikos in the defense of his lands against the Turks. After numerous attempts in subduing the Turks, the rapidly crumbling Byzantine Empire was forced to enlist the help of Serbia. The Turks were looting and pillaging the countryside and the two armies converged at the Gallipoli peninsula where the Turks were decisively defeated. Out of gratitude to Serbia, the town of Kucovo was donated.

Upon Stefan Dragutin's death in 1316, Milutin conquered most of his lands including Belgrade. That was not acceptable for king Charles I of Hungary, who started to seek allies against Serbia, including those among Albanian nobles, who were also receiving support from Pope John XXII. Milutin started to persecute Catholics which led to the crusade started by Pope John XXII.[10][11]

In 1318, there was an open revolt of Albanian nobles against the rule of Stefan Milutin, which is sometimes credited to be incited by Prince Philip I of Taranto and Pope John XXII in order to weaken Stefan Milutin's rule. Milutin suppressed the rebels without much difficulty.[10] In 1319, Charles I of Hungary regained control over Belgrade and the region of Mačva while Milutin held control in Braničevo. In the year 1314 Milutin's son Stefan Dečanski rebelled against his father, but was captured and sent to exile in Constantinople. For the rest of Milutin's reign his youngest son Stefan Constantine was considered as heir to the throne, but in the spring of 1321 Stefan Dečanski returned to Serbia and was pardoned by his father.

Serbia's economic power grew rapidly in the 14th century, and Milutin's power was based on new mines, mostly in Kosovo territory. During his regin, Novo Brdo was the richest silver mine in the Balkans, while another important mines were Trepča and Janjevo. He produced imitations of Venetian coins, which contained seven-eighths of silver compared to their coins. They were banned by the Republic of Venice, but Milutin used them to wage civil war against Dragutin. Later, Novo Brdo became an internationally important silver mining site and significant strategic position, while in the 15th century, Serbia and Bosnia combined produced over 20% of European silver.[12][13]

Time of his reign was marked hostility to Catholicism, particularly in coastal regions, inhabited by religiously mixed population, that included Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians.[10][11]

Family

Stefan Uroš II Milutin was married five times.

By his first wife, Jelena, a Serbian noblewoman, he had:

- King Stephen Uroš III[14]

By his second wife, Helena, daughter of sebastokratōr John I Doukas of Thessaly, he possibly had:

- King Stefan Konstantin (estimates of his age and maternity vary)

By his third wife, Elizabeth, daughter of King Stephen V of Hungary and Elizabeth the Cuman, he had:

- Anna, called Neda or Domenica, who married Michael Asen III ("Shishman") of Bulgaria[15]

- Zorica or Carica

By his fourth wife, Anna, the daughter of George Terter I of Bulgaria and Maria of Bulgaria, he probably had no children.

By his fifth wife Simonis, the daughter of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos and Irene of Montferrat, he had no children.

Aftermath and legacy

At the end of Milutin's life Serbia was second in strength in Southeast Europe after Hungary. During his reign many court ceremonials were taken over from the Byzantine court and Byzantine culture overflowed into Serbia. After his death a short civil war followed, after which the Serbian throne was ascended by his eldest son, Stefan Dečanski. Around 1460, the remains of the king were carried to Bulgaria from the Hilandar monastery and were stored in various churches and monasteries until being transferred to St Nedelya Church after it became a bishop's residence in the 18th century. With some interruptions, the remains have been preserved in the church ever since and the church acquired another name, Holy King („Свети Крал“, „Sveti Kral“), in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Stefan Milutin is mentioned in the Dante Alighieri's narrative poem Divine Comedy with the characteristics of counterfeiters due to the copying of Venetian money.[16][12]

He is included in The 100 most prominent Serbs list.

Foundations

King Stefan Milutin founded a hospital in Constantinopole, which later became a medical school.[17] He also erected many churches and monasteries in Serbian lands.[18][19][20] As a ktetor, he was praised in works of Danilo II, Serbian Archbishop (1324–1337) and other medieval sources.[21][22]

- Vitovnica Monastery near Petrovac, Serbia (1291)

- Church of St. Nicetas in Banjane, North Macedonia (ca. 1300)

- Our Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren (1306–1307)

- Church of Saint Nicetas the Goth in Banjane, North Macedonia (1307–1310)

- Serbian Monastery of Holy Archangels, Jerusalem (1312)[23]

- The King's Church of the Studenica Monastery in Kraljevo, Serbia (1313–1314)

- Church of St. George in Kumanovo, North Macedonia (1313–1318)

- Banjska Monastery near Zvečan (1318)

- Gračanica Monastery in Gračanica (1321)

- Church of Trojeručica near Skopje, North Macedonia (13-14th century)

- Church of Saint Constantine the Great in Skopje, North Macedonia (13-14th century)

- Bukovo Monastery near Negotin, Serbia (13-14th century)

- Koroglaš Monastery near Negotin, Serbia (14th century)

- Vratna Monastery near Negotin, Serbia (14th century)

Reconstructions

- Monastery of Saints Sergius and Bacchus near Shirq (1293)

- Church of the Virgin Hodegetria in Mušutište (1314—1315)

- Church of Entrance of the Theotokos of the Hilandar Monastery at the Mount Athos, Greece (1320)

- Church of St. Peter near Bijelo Polje, Montenegro (1320)

- Church of St. George near Skopje, North Macedonia (13-14th century)

- Monastery of St. Nicholas in Kožle, North Macedonia (13-14th century)

- Orahovica Monastery near Priboj, Serbia (13-14th century)

- Treskavec Monastery near Prilep, North Macedonia (14th century)

See also

References

- ^ Dvornik 1962, p. 110-111, 119.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 217-224, 255-270.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 49-52, 61-62.

- ^ Curta 2019, p. 668-667.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 50.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 221, 259.

- ^ Krstić 2016, p. 33–51.

- ^ Krstić 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 219.

- ^ a b c Fine 1994, p. 262.

- ^ a b Živković & Kunčer 2008, p. 203.

- ^ a b Vuković & Weinstein 2002, p. 21–24.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Nicol 1984, p. 254.

- ^ Mladjov 2011: 613-614.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 257.

- ^ Todić 1999, p. 29, 347.

- ^ Ćurčić 1979, p. 5-11.

- ^ Mileusnić 1998, p. 18, 54, 168.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Thomson 1993, p. 103-134.

- ^ Ivanović 2019, p. 103–129.

- ^ The Sabaite heritage in the Orthodox Church from the fifth century to the present. J. Patrich. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters rn Departement Oosterse Studies. 2001. p. 404. ISBN 90-429-0976-5. OCLC 49333502.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ćurčić, Slobodan (1979). Gračanica: King Milutin's Church and Its Place in Late Byzantine Architecture. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271002187.

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004395190.

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813507996.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526. London & New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781850439776.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Isailović, Neven (2016). "Living by the Border: South Slavic Marcher Lords in the Late Medieval Balkans (13th-15th Centuries)". Banatica. 26 (2): 105–117.

- Ivanović, Miloš; Isailović, Neven (2015). "The Danube in Serbian-Hungarian Relations in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Tibiscvm: Istorie–Arheologie. 5: 377–393.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2019). "Serbian Hagiographies on the Warfare and Political Struggles of the Nemanjić Dynasty (from the Twelfth to Fourteenth Century)". Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 103–129.

- Jireček, Constantin (1911). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 1. Gotha: Perthes.

- Jireček, Constantin (1918). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 2. Gotha: Perthes.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2014). "A Millennium of Belgrade (Sixth-Sixteenth Centuries): A Short Overview" (PDF). Balcanica (45): 71–96. doi:10.2298/BALC1445071K.

- Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2016). "The Rival and the Vassal of Charles Robert of Anjou: King Vladislav II Nemanjić". Banatica. 26 (2): 33–51.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (1998). Medieval Monasteries of Serbia (4th ed.). Novi Sad: Prometej. ISBN 9788676393701.

- Miller, William (1923). "The Balkan States, I: The Zenith of Bulgaria and Serbia (1186-1355)". The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 4. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 517–551.

- Mladjov, Ian (2011). "The Bulgarian Prince and would-be Emperor Lodovico". Bulgaria Mediaevalis. 2: 603–617.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1984) [1957]. The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages (2. expanded ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521261906.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993) [1972]. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439916.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Thomson, Francis J. (1993). "Archbishop Daniel II of Serbia: Hierarch, Hagiographer, Saint: With Some Comments on the Vitae regum et archiepiscoporum Serbiae and the Cults of Mediaeval Serbian Saints". Analecta Bollandiana. 111 (1–2): 103–134. doi:10.1484/J.ABOL.4.03279.

- Todić, Branislav (1999). Serbian Medieval Painting: The Age of King Milutin. Belgrade: Draganić. ISBN 9788644102717.

- Uzelac, Aleksandar B. (2011). "Tatars and Serbs at the end of the Thirteenth Century". Revista de istorie Militara. 5–6: 9–20.

- Uzelac, Aleksandar B. (2015). "Foreign Soldiers in the Nemanjić State - A Critical Overview". Belgrade Historical Review. 6: 69–89.

- Vuković, Milovan; Weinstein, Ari (2002). "Kosovo Mining, Metallurgy, and Politics: Eight Centuries of Perspective". Journal of the Minerals, Metals and Materials Society. 54 (5): 21–24. Bibcode:2002JOM....54e..21V. doi:10.1007/BF02701690. S2CID 137591214.

- Živković, Tibor; Kunčer, Dragana (2008). "Roger - the forgotten Archbishop of Bar" (PDF). Историјски часопис. 56: 191–209.