Kill, Baby, Kill

| Kill, Baby, Kill | |

|---|---|

Italian film poster by Averardo Ciriello[1] | |

| Italian | Operazione paura |

| Directed by | Mario Bava |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Antonio Rinaldi[2] |

| Edited by | Romana Fortini[2] |

| Music by | Carlo Rustichelli |

| Color process | Eastmancolor |

Production company | F.U.L. Films |

| Distributed by | Internazionale Nembo Distribuzione Importazione Esportazione Film |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes[2] |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Box office | ₤201 million |

Kill, Baby, Kill (Italian: Operazione paura, lit. 'Operation Fear')[3] is a 1966 Italian gothic horror film directed by Mario Bava and starring Giacomo Rossi Stuart and Erika Blanc. Written by Bava, Romano Migliorini, and Roberto Natale, the film focuses on a small Carpathian village in the early 1900s that is being terrorized by the ghost of a murderous young girl.

Overseen by one-time producers Nando Pisani and Luciano Catenacci of F.U.L. Films, Kill, Baby, Kill was considered to be a small-scale project compared to Bava's earlier films, as it was made without internationally recognized stars or the support of a major distributor. Although a complete script was written by Migliorini and Natale prior to the start of production, Bava claimed that much of the film was improvised. Shot partially on location in Calcata, Faleria and at the Villa Grazioli in 1965, the film underwent a troubled production due to F.U.L. Films running out of money during principal photography, prompting the cast and crew to finish the film in the knowledge that they would not be paid for their work. In post-production, the score had to be compiled from stock music created for earlier film productions.

Although the film's commercial performance during its initial Italian theatrical release was limited, its domestic run outgrossed those of Bava's previous horror films; abroad, it garnered positive notices from Variety and the Monthly Film Bulletin. With the re-evaluation of Bava's filmography, Kill, Baby, Kill has been acclaimed by filmmakers and critics as one of the director's finest achievements; it was placed at number 73 on a Time Out poll of the best horror films.[4]

Plot

In 1907, Dr. Paul Eswai is sent to the Carpathian village of Karmingam to perform an autopsy on Irena Hollander, a woman who died under mysterious circumstances in an abandoned church. Monica Schufftan, a medical student who has recently returned to visit her parents' graves, is assigned as his witness. During the autopsy, they find a silver coin embedded in Hollander's heart.

The local villagers are accustomed to medicinal practices and superstitions Eswai finds preposterous, and claim that Karmingam is haunted by the ghost of a young girl who curses those she visits. After Nadienne, the daughter of local innkeepers, is visited by the girl, a ritual to reverse the curse is performed by Ruth, the village witch. That evening, Eswai goes to meet with a colleague, Inspector Kruger, at the villa of Baroness Graps. When he arrives at the large, decrepit house, the Baroness informs him that she knows of no such Kruger. Upon leaving, Eswai encounters the ghostly young girl.

Meanwhile, Monica has a nightmare about the child, and awakens to find a doll at the foot of her bed. She runs into Eswai in the street, and he offers to take her to the inn so she can sleep. At the inn, Eswai discovers that Nadienne is wearing a leech vine around her body as part of Ruth's treatment. Believing this procedure to be causing her greater suffering, he removes the vine despite her family's concerns. In the local cemetery, Eswai finds two gravediggers burying Kruger's corpse, who has been shot in the head. Simultaneously, Nadienne is awoken by the young girl at her window, who compels her to impale herself with a candelabra.

Eswai and Monica are informed by Karl, the burgomeister, that the ghostly girl is Melissa Graps, the dead daughter of the Baroness, and that she is responsible for the deaths of Hollander and Kruger; he also reveals to Monica that the Schufftans were not her real parents. When he goes to retrieve evidence proving so, he is compelled by Melissa into destroying the documents and killing himself. Turned away by Nadinne's father due to her death, Monica and Eswai attempt to get the reluctant villagers' attention by ringing the church bell. Inside the church, they find a secret passageway, where Monica experiences déjà vu. They discover the Graps' family tomb, which includes that of Melissa, who died in 1887, aged seven.

They find a staircase leading out of the tomb, which takes them inside the Villa Graps, where the Baroness confronts them in the hallway. She reveals that Melissa was trampled to death while fetching a ball during a drunken festival. Melissa appears in the room, and Monica suddenly vanishes through a doorway. Eswai chases after her through a repeating series of doorways; in his pursuit, he confronts a doppelgänger of himself, after which he is left locked in a room and subsequently spirited out of the villa. He loses consciousness, and awakens in Ruth's home. Ruth explains that the coins found in the hearts of the victims have been placed there by her as talismans to ward off supernatural powers of the Baroness, who has invoked her daughter's ghost to punish the villagers, and that she intends to kill the Baroness to avenge Karl, who was her lover.

In the villa, the Baroness reveals to Monica that she is her daughter, and Melissa her older sister; following Melissa's death, the Baroness' servants, the Schufftans, sent Monica to be raised and educated in Gräfenberg for her protection. Melissa's ghost appears, chases Monica down the staircase into the tomb, and urges her to throw herself from a nearby balcony. Ruth arrives and confronts the Baroness. The Baroness stabs her through the chest with a fire poker, but Ruth manages to strangle her to death before dying, thus laying Melissa's soul to rest; Eswai arrives in time to save Monica. Reunited, the pair leave Villa Graps as the sun rises in the distance.

Cast

- Giacomo Rossi Stuart as Dr. Paul Eswai

- Erika Blanc as Monica Schufftan

- Fabienne Dali as Ruth

- Giovanna Galletti as Baroness Graps

- Luciano Catenacci as Karl

- Piero Lulli as Inspector Kruger

- Micaela Esdra as Nadienne

- Franca Dominici as Martha

- Giuseppe Addobbati as Innkeeper

- Mirella Panfili as Irena Hollander

- Valerio Valeri as Melissa Graps

Production

Background

Kill, Baby, Kill marked Mario Bava's return to gothic horror, having previously directed Black Sabbath and The Whip and the Body in 1963.[2] In later years, he claimed to have made the film as a result of a bet with "some Americans"; in contrast to his earlier horror films, it was neither made with American or British leads, nor did it experience creative interference from a major distributor like American International Pictures (AIP).[2][5] Bava biographer Tim Lucas stated that retrospective reviews of Italian horror films described the period between 1957 and 1966 as the genre's "Golden Age", with Kill, Baby, Kill often being described as its "Grand Finale", as it was among the last of these films from Italy to be widely distributed.[6]

The film was funded by a small Italian company, F.U.L. Film.[2] The film's credited producers were Nando Pisano and Luciano Catenacci; this was the only film they produced.[7] Pisano was a production manager who had worked on films ranging from Roberto Rossellini's Where Is Freedom? to Giorgio Bianchi's The Orderly, while Catenacci worked primarily as an actor under the name "Max Lawrence".[7] Catenacci also served as the film's production manager and portrayed the character of Karl.[7] Lucas has estimated that the film's budget to be lower than those of Bava's films that were distributed by AIP in the United States, estimating it to be well below $50,000.[8]

Writing and pre-production

The screenplay is credited to the writing team of Romano Migliorini and Roberto Natale, who had previously written two horror films for Massimo Pupillo, Francesco Merli and Ralph Zucker: Bloody Pit of Horror and Terror-Creatures from the Grave.[5] Both films shared crew members and studio space with Kill, Baby, Kill; aside from using some of the earlier films' set furnishings, the set housing the Graps family crypt in Kill, Baby, Kill had been used as the Crimson Executioner's dungeon in Bloody Pit of Horror.[5] Lucas notes that the script has two possible cinematic antecedents: the 1944 Rathbone/Bruce Sherlock Holmes film The Scarlet Claw, in which Holmes and Dr. Watson are summoned to a small town where a series of murders — the most recent of which is of a woman who bled to death while ringing the local church bell — have been attributed to a ghost, and 1960's Village of the Damned (based on the 1957 novel The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham), in which a group of aliens resembling blonde children menace a village by psychically compelling residents into committing suicide.[9]

Bava claimed in an interview that the film was improvised on the spot from a script of only 30 pages;[10] Lucas has suggested that the screenplay for the film may have been based on an early screenplay for La vendetta di Lady Morgan by Natale and Migliorini.[11] Film historian Roberto Curti has refuted this, noting that Kill Baby Kill's shooting script, titled Le macabre ore della paura (lit. 'The Macabre Hours of Fear'), featured detailed dialogue and a completed storyline.[11] The screenplay stored in Rome's Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia library was deposited there on 5 April 1966, as screenplays are generally deposited there before shooting has started.[11] Curti noted that La vendetta di Lady Morgan began shooting on 26 July 1965, was submitted to the Ministerial Censorship Commission on 1 October, and was released on 16 December. This screenplay also revealed that ideas that had already been used in Bava's previous films but were discarded, such as victims returning from the dead as zombies.[11] The film's screenplay also includes scenes that remain in the film, such as the scene of the spiral staircase and the scene where Dr. Eswai chases his doppelgänger over and over into the same room.[11]

Kill, Baby, Kill marked Bava's third and final collaboration with actor Giacomo Rossi Stuart, following The Day the Sky Exploded and Knives of the Avenger.[7] Actress Erika Blanc was cast as Monica Schuftan in the film, and claimed the film was only the second feature she made, despite filmographies suggesting otherwise.[12][13] Bava auditioned hundreds of young girls to play the part of Melissa Graps, but was unable to find one. Bava eventually cast Valerio Valeri, who was the son of his concierge.[14] According to Blanc, Valeri was not happy with the role due to the need for him to wear a dress, and that Bava would goad his performance by referring to him as "Valeria".[14] The actress also noted that fellow cast member Fabienne Dali was so committed to her role as the witch Ruth that she performed tarot card readings for the cast and crew.[15]

Filming and special effects

Lucas described the production of Kill, Baby, Kill as being plagued by "bad luck" as the film ran out of money while filming.[16] Blanc stated that the cast and crew were only paid for their first two weeks working on the film, and agreed to complete it without pay due to their affection for Bava.[17] Bava's friend Luigi Cozzi stated that Bava was never paid for his work on the film.[17] According to Bava, the film was shot in 12 days in 1965.[2][18] Blanc has refuted this statement, the film was shot in "maybe twenty" days, while Bava's son and assistant director Lamberto stated the film took about four weeks to finish.[5]

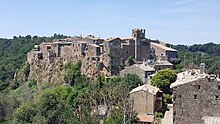

Several exterior scenes for Karmingam were filmed on location in the medieval towns of Calcata and Faleria, while the façade and several interiors of Villa Grazioli in Grottaferrata were used to represent Villa Graps.[19] All other sequences, including interiors and the cemetery scenes, were shot at Titanus Appia Studios, where it was one of the last films to be shot there before it predominantly became a distribution company.[18] Lamberto Bava described Calcata during this period as "Abandoned, constructed on a mountain of tufa, a material that has crumbled over the centuries" and that around the late 1960s the area "became a kind of hippie community."[19]

The special effects, such as the distorted vision at the beginning of the film, were created using a sheet of distorted "water glass" created by Bava's father Eugenio when he was a camera operator on silent films.[20] Other budgetary concerns led to Bava shooting the film without a crane, leading him to film with a makeshift seesaw to shoot certain scenes.[21] Several shots of Melissa were filmed with Valeri performing the actions in reverse, lending an uncanny feel to the character's movements. The disappearance of her ghost at the end of the film was accomplished by dimming the light that projected Valeri's reflection onto a sheet of angled glass.[22]

Music

The film's score is credited to Carlo Rustichelli,[2][23] but is actually a collection of library music, featuring works by Rustichelli and other composers who had worked with Bava.[23] Lucas suggested that the use of stock music, as opposed to an original score, was due to the low budget of the production.[24] Other music includes Francesco De Masi music from The Murder Clinic, the lullaby piece of music heard in the films titles was composed by Armando Trovajoli originally used in the comedy film What Ever Happened to Baby Toto?.[23][25] Music from previous films includes pieces composed by Rustichelli for The Long Hair of Death, Blood and Black Lace, The Whip and the Body and Roman Vlad's music from I Vampiri.[26][23][27][23][28] When asked about the film's music, Rustichelli admitted that he did not remember the film nor any music he composed for it.[22]

Release

Kill, Baby, Kill was released in Italy on 8 July 1966, and was distributed by I.N.D.I.E.F.[2] By the time the film was released, Blanc was known for appearing in various spy films. One of these, Agente S 03: Operazione Atlantide, led to Kill, Baby, Kill being released as Operation paura in Italy.[13] Released during the height of the Italian vacation season, it was shown in Rome for only four days in August before vanishing from circulation.[16] It grossed a total of 201 million Italian lira domestically on its initial theatrical release.[2] Although Curti has described this figure as "nondescript", the film was the highest-grossing horror film of Bava's career at the time of its domestic run in Italy, outperforming Black Sunday and Black Sabbath, which were his biggest contemporary successes in the international market.[29][30] Bava chose not to direct another horror film until 1968, when he shot Hatchet for the Honeymoon.[30][31]

The film was released in the United States on 8 October 1967, where it was distributed by Europix Consolidated Corporation alongside Sound of Horror; the double feature was advertised as "The S&Q Show", with the tagline "You'll Shiver and Quiver with Kill Baby Kill — and Shake and Quake with Sounds of Horror!".[2][29] The pairing proved to be a hit on the drive-in circuit, and both films were licensed for TV syndication the following year.[29] In the United Kingdom, it was retitled Curse of the Dead and released by Marigold Films in 1967.[2][32] In West Germany, the film was released in 1970 as Die Toten Augen des Dr. Dracula (lit. 'The Dead Eyes of Dr. Dracula') by Alpha Film, a small company that went out of business shortly after its release.[33] Europix re-issued the film under the title Curse of the Living Dead, with one reel removed, as part of a triple feature called "Orgy of the Living Dead" in the United States in 1972, alongside The Murder Clinic (retitled Revenge of the Living Dead) and Malenka (Fangs of the Living Dead). Between March and June 1973, the triple bill grossed over $750,000 from more than 400 playdates.[34] In Japan, the film was released in 1973 by 20th Century Fox.[5][35]

Home media

Kill, Baby, Kill was released on DVD in September 2000 by VCI.[36] In 2007, the home video company Dark Sky Films attempted to release Kill, Baby, Kill on DVD in North America.[37] After assuming the rights had been secured, the company proceeded to purchase the licensing rights to the film for the United States.[37] Dark Sky Films was then sued by Alfredo Leone, who stated that he owned the rights to the film and had recently sold the rights to the company Anchor Bay Entertainment.[37] The courts sided with Leone and Anchor Bay, while Dark Sky Films who had already pressed DVDs of the film had to cancel the release.[37] The film was then released on DVD by Anchor Bay Entertainment in one of two five-film boxed sets of Bava's horror films,[38] alongside Black Sunday, Black Sabbath, The Girl Who Knew Too Much, and Knives of the Avenger.[39]

The film was released on Blu-ray and special-edition DVD for the first time in the United Kingdom on 11 September 2017, by Arrow Video, followed by a release in North America on 10 October 2017, through Kino Lorber.[40][41]

Critical reception

Contemporaneous

From contemporaneous reviews, Tom Milne of the Monthly Film Bulletin noted that though "narrative has never been Bava's strong point, but with Operazione Paura he has happily found a story in which atmosphere is everything, and the result is even more splendid visually than Sei Donne per l'Assasino".[42] The review also compared the film to that of Beauty and the Beast and The Turn of the Screw and the work of Georges Franju.[42] Stuart Byron ("Byro") of Variety commented that "every element of light and color has been carefully orchestrated by Bava to achieve a tantalizing and dramatic effect" and "plot details are juggled expertly to achieve needed scare effects" while "there's no attempt to the especial original here - it's just the same old Gothic elements, but handled so skillfully as to revitalize the genre."[43][29] The review concluded that "perhaps his pix will remain in the province of buffs, but Bava - whose sole international success was with Black Sabbath - deserves a small but firm niche in film history."[43] According to Blanc, the film received a standing ovation from director Luchino Visconti upon its opening in Rome.[44]

Retrospective

The Carpathian village of [Kill, Baby, Kill] is among Mario Bava's most indelible achievements — a physicalized realm of fear. [...] Bava uses the location as a source of found German expressionism, merging the canted windows and seemingly irrational angles of streets and stacked buildings with candy-colored cinematography and pointedly artificial sets. This contrast between the discovered and the created suggests a porous boundary between reality and subjectivity, the past and present, and the antiquated and modernized. In [Kill, Baby, Kill], as in many other Bava films, a character can stroll recognizable streets into dimensions that are rooted in their own psyches, trapping themselves in temporal loops that may embody encroaching madness. Bava renders insanity as both a place and a contagion.

From retrospective reviews, Slant Magazine called it "arguably Bava's greatest achievement", giving it four stars out of a possible four.[46] Slant also ranked it number 80 on their list of the top 100 horror films of all time.[45] Bava biographer Tim Lucas described the film as a "mixture of pure poetry and pulp thriller, distinguished by vivid, hallucinogenic cinematography...jolts into the realms of free-form delirium and dementia. The spectre of little Melissa Graps, with her white lace dress and bouncing white ball, is perhaps the most influential icon of Italian horror cinema, having been copied in countless other films, notably Federico Fellini...and the film itself has been an admitted influence on such directors as Martin Scorsese and David Lynch;" he and Lamberto Bava have identified it as their personal favorites of Bava's films.[5][47][48] In the 2010s, Time Out polled authors, directors, actors and critics who had worked in the horror genre to vote for their top horror films.[49] Kill, Baby, Kill at number 56 on the top 100.[49]

Taste of Cinema observed that "Martin Scorsese called this Bava's best film...probably the most successful realization of Gothic horror-meets-bad-acid-trip."[50] Scott Beggs said "This might be Bava’s greatest achievement, and he doesn’t hold out on the lush production design or the trippy camera tricks."[51] Derek Hill designated Kill, Baby, Kill! as "one of his best efforts and what is arguably one of the most effective and chilling supernatural gothic horror films of all time. It has influenced Federico Fellini...Martin Scorsese...Kill, Baby, Kill! creates such a palpable mood of dread and oppression in its first few minutes and so effectively sustains the momentum until the last frame that it is easy to see why it has cast such a quiet legacy on other filmmakers."[52] Patrick Legare of AllMovie called the film "an eerie and atmospheric effort that reflects many of the elements that have made the popular Italian director's films so compelling: excellent cinematography and strong performances from the talented cast."[53]

Pablo Kjolseth of Turner Classic Movies praised the film's visuals, writing: "If you value mood and atmosphere over modern visceral thrills there's a good chance you'll land in the latter camp. Rich color schemes, crumbling elegant buildings, mist-covered cobble-stoned streets, dusty taverns, swirling spiral stairs, and endless halls with creepy décor and art all help establish a handful of the exteriors and interiors that make the film magical."[38]

Legacy and analysis

Kill, Baby, Kill has been credited as an inspiration on numerous filmmakers, as the imagery of the character Melissa Graps — a young girl with a bouncing ball who serves as a symbol of wickedness — has been referenced in several contemporary horror films. Fellini was inspired by this imagery, and used it in his segment "Toby Dammit," from the anthology film Spirits of the Dead (1968).[54] After hearing about Fellini's use of imagery in the film, Bava went to see Spirits of the Dead and reflected on this screening stating "That ghost child with the bouncing ball... it's the same ideas as in my film, exactly the same! I later mentioned this to Giulietta Masina and she just shrugged her shoulders, smiling and said, 'Well, you know how Federico is....'"[55]

The imagery of the film also influenced other works, such as Alessandro Capone's debut film Witch Story, which also features a spectral young girl with a white bouncing ball. Among English-language films influenced by Bava's film, Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now features a character in search of a hooded figure resembling his blonde-haired daughter, only to discover the figure to be a homicidal dwarf who kills him in a manner he has foreseen in premonitions.[56] In Asia, several productions also feature a spectral young girl with a white bouncing ball, such as Wellson Chin's 1997 film Tamagotchi and the anime series Pokémon, specifically the episodes "Abra and the Psychic Showdown" and "Haunter vs. Kadabra".[56] In the United States, the imagery is also seen in the 2002 horror film FeardotCom.[57]

Visually, the film has been noted as an inspiration on Dario Argento's Suspiria.[58] The film's use of color has also been noted as an inspiration on the visuals of Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ.[38]

Scholar David Sanjek also noted the film's use of the child symbolizing evil as a pioneering motif in the genre: "Kill, Baby, Kill, a film of genuine poetic power and visual ingenuity, successfully inverted gothic stereotypes of good and evil by having the power of good embodied by a dark-haired witch while evil is represented by an angelic, blonde young girl."[59]

Footnotes

- ^ Curti 2015, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Curti 2015, p. 159.

- ^ Brunetta 2009, p. 201.

- ^ "Best Horror Movies - 100 Scary Movies To Watch Now, Ranked By Experts". Timeout.com. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Lucas 2013, p. 664.

- ^ Lucas 2013, p. 667.

- ^ a b c d Lucas 2013, p. 669.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:10:50.

- ^ Lucas 2013, p. 664-7.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:9:40.

- ^ a b c d e Curti 2015, p. 162.

- ^ Curti 2015, p. 163.

- ^ a b Lucas 2017, 0:15:00.

- ^ a b Lucas 2017, 0:38:05.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:26:29.

- ^ a b Lucas 2017, 1:19:28.

- ^ a b Lucas 2017, 0:10:13.

- ^ a b Lucas 2017, 0:6:10.

- ^ a b Lucas 2013, p. 668.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:1:02.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:16:10.

- ^ a b Lucas 2013, p. 672.

- ^ a b c d e Lucas 2017, 0:1:54.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:19:30.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:35:20.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:17:30.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:52:50.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:55:30.

- ^ a b c d Lucas 2013, p. 681.

- ^ a b Curti 2015, p. 165.

- ^ Curti 2017, p. 20.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 1:20:43.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 1:20:54.

- ^ Lucas 2013, p. 681-3.

- ^ "呪いの館". Movie Walker Press (in Japanese). Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Title Wave". Billboard. 27 May 2006. p. 146 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Shipka 2011, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Kjolseth, Pablo. "Mario Bava Boxed Set". Turner Classic Movies. Home Video Reviews. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ Kehr, David (10 April 2007). "New DVDs". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Upcoming Arrow Video Blu-ray Releases". Blu-ray.com. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Kill, Baby, Kill! Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ a b Mulne, Tim (July 1967). "Operazione Paura (Curse of the Dead), Italy, 1966". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 34, no. 402. The British Film Institute. p. 104.

- ^ a b Variety's Film Reviews 1968-1970. Vol. 12. R. R. Bowker. 1983. There are no page numbers in this book. This entry is found under the header "October 30, 1968". ISBN 0-8352-2792-8.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 0:3:08.

- ^ a b "The 100 Best Horror Movies of All Time". Slant Magazine. 25 October 2019. p. 5. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ed (15 June 2003). "Kill, Baby...Kill!". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Lucas 2017, 1:23:07.

- ^ Thompson, Lang. "TCM Imports - The Films of Mario Bava". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b Clarke, Cath; Calhoun, Dave; Huddleston, Tom (19 August 2015). "The 100 best horror films: the list". Time Out. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Mason, Scot (13 May 2014). "10 Essential Mario Bava Films Every Horror Fan Should See". Taste of Cinema. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Beggs, Scott. "Mario Bava's 'Kill, Baby, Kill!'". Film School Rejects. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Hill, Derek. "Kill, Baby...Kill!". Images Journal. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Legare, Patrick. "Kill, Baby, Kill (1966)". AllMovie. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Karola 2003, p. 228.

- ^ Lucas 2013, p. 686.

- ^ a b Lucas 2013, p. 687.

- ^ Acerbo & Pisoni 2007, p. 227.

- ^ Heller-Nicholas 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Sanjek 2007, p. 426.

References

- Acerbo, Gabriele; Pisoni, Roberto (2007). Kill Baby Kill!: Il cinema di Mario Bava (in Italian). Un mondo a parte. ISBN 978-8-889-48113-4. OCLC 860440097.

- Brunetta, Gian Piero (2009). The History of Italian Cinema: A Guide to Italian Film from Its Origins to the Twenty-first Century. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11988-5. OCLC 436979203.

- Curti, Roberto (2015). Italian Gothic Horror Films, 1957-1969. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476619897. OCLC 946552693.

- Curti, Roberto (2017). Italian Gothic Horror Films, 1970-1979. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476629605.

- Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra (1 December 2015). Suspiria. Devil's Advocates. New York: Auteur. ISBN 978-0-993-23847-5. OCLC 936308469.

- Hughes, Howard (2011). Cinema Italiano - The Complete Guide From Classics To Cult. London - New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-608-0. OCLC 961684174.

- Karola (2003). "Italian Cinema Goes to the Drive-In: The Intercultural Horrors of Mario Bava". In Rhodes, Gary Don (ed.). Horror at the Drive-in: Essays in Popular Americana. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-41342-3. OCLC 606934557.

- Lucas, Tim (2017). Audio commentary with Tim Lucas (Blu ray). Arrow Films. FCD1573.

- Lucas, Tim (2013). Mario Bava - All the Colors of the Dark. Video Watchdog. ISBN 978-0-9633756-1-2.

- Sanjek, David (1 December 2007). "Fans' notes: The horror film fanzine". The Cult Film Reader. London: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-21923-0. OCLC 746250976.

- Shipka, Danny (2011). Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786486090. OCLC 746880411.

Further reading

- Cozzi, Luigi (2011). Mario Bava, Master of Horror. Profondo Rosso. ISBN 978-8-895-29457-5.

- Pezzotta, Alberto (1995). Mario Bava. Il castoro cinema (in Italian). Rome: Il Castoro. ISBN 978-8-880-33042-4. OCLC 246775533.