Mende Kikakui script

| Mende Kikakui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

| Creator | Mohamed Turay |

Time period | 1917 — present |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Mende |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Mend (438), Mende Kikakui |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Mende Kikakui |

| U+1E800–U+1E8DF Final Accepted Script Proposal | |

The Mende Kikakui script is a syllabary used for writing the Mende language of Sierra Leone.

History

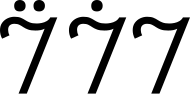

The script was devised by Mohamed Turay (ca. 1850-1923), an Islamic scholar, at a town called Maka (Barri Chiefdom, southern Sierra Leone) around 1917. His writing system, an abugida called 'Kikakui' after the first three consonant sounds, was inspired by the Arabic abjad, the Vai syllabary and certain indigenous Mende pictograms and cryptographic characters. It originally had around 42 characters.[1]

One of Turay's Quranic students, as well as his nephew and son-in-law, was a young Kuranko man named Kisimi Kamara. He adjusted and developed the script further with help from his brothers, adding more than 150 other syllabic characters. Kamara popularized the script, travelling widely in Mendeland and becoming a well-known figure, eventually establishing himself as one of the most important chiefs in southern Sierra Leone in the mid 20th century. He is sometimes erroneously cited as the inventor of Kikakui.[2]

The script achieved widespread use for a time, particularly for financial and legal documents.[3] The colonial authorities' choice in the 1930s to use Diedrich Hermann Westermann's Africa Alphabet, based on the Latin script, for writing local languages pushed Kikakui into the background.[1] It is now considered a "failed script".[4]

Kikakui is still used today by an estimated few hundred individuals.[1]

Usage

Methodist missionaries in Sierra Leone considered using Kikakui to transliterate the Bible, but ultimately selected the Africa Alphabet due to the supposed efficiency and ease of writing of an alphabet. Experience, however, proved that a syllabary such as Kikakui was better suited for teaching and learning languages such as Mende that have an 'open syllable' or consonant-vowel (CV) structure.[5]

The script was originally used by specialists who served as record-keepers for the courts and benefited from having a monopoly in its usage. This created resistance to foreign missionaries' attempt to use Kikakui as a language for general instruction and made it seem too 'secret' for local Christians' efforts to promulgate the Bible in a widely understood script, so its usage in a Christian context dwindled. The script is, however, still used for transcribing passages of the Quran.[6]

Characters

There were an original 42 syllabic characters that were ordered according to sound and shape, while 150 more characters were later added without the same consistency to the character set. Some of the initial 42 characters resemble an abugida, given the standard ability for a reader to discern the vowels from seeing the character, as indicated by dots in consistent locations, but such uniformity vanishes in the remaining 150 characters. Glyphic variants have been found for certain characters.

Additionally, digits are encoded by indicating the place value on each digit for a number, with the units digit alone having no special indication. Beyond the 10s digit, the further digits are written on top of the base place value indicator, which increases in vertical lines from 2 at the 100s place (indicating 2*10 + the digit above) to the millionths digit that is encoded (which has 6). All of the different possible digits are encoded separately.

Unicode

Mende Kikakui script was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0.

The Unicode block for Mende Kikakui is U+1E800–U+1E8DF:

| Mende Kikakui[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1E80x | 𞠀 | 𞠁 | 𞠂 | 𞠃 | 𞠄 | 𞠅 | 𞠆 | 𞠇 | 𞠈 | 𞠉 | 𞠊 | 𞠋 | 𞠌 | 𞠍 | 𞠎 | 𞠏 |

| U+1E81x | 𞠐 | 𞠑 | 𞠒 | 𞠓 | 𞠔 | 𞠕 | 𞠖 | 𞠗 | 𞠘 | 𞠙 | 𞠚 | 𞠛 | 𞠜 | 𞠝 | 𞠞 | 𞠟 |

| U+1E82x | 𞠠 | 𞠡 | 𞠢 | 𞠣 | 𞠤 | 𞠥 | 𞠦 | 𞠧 | 𞠨 | 𞠩 | 𞠪 | 𞠫 | 𞠬 | 𞠭 | 𞠮 | 𞠯 |

| U+1E83x | 𞠰 | 𞠱 | 𞠲 | 𞠳 | 𞠴 | 𞠵 | 𞠶 | 𞠷 | 𞠸 | 𞠹 | 𞠺 | 𞠻 | 𞠼 | 𞠽 | 𞠾 | 𞠿 |

| U+1E84x | 𞡀 | 𞡁 | 𞡂 | 𞡃 | 𞡄 | 𞡅 | 𞡆 | 𞡇 | 𞡈 | 𞡉 | 𞡊 | 𞡋 | 𞡌 | 𞡍 | 𞡎 | 𞡏 |

| U+1E85x | 𞡐 | 𞡑 | 𞡒 | 𞡓 | 𞡔 | 𞡕 | 𞡖 | 𞡗 | 𞡘 | 𞡙 | 𞡚 | 𞡛 | 𞡜 | 𞡝 | 𞡞 | 𞡟 |

| U+1E86x | 𞡠 | 𞡡 | 𞡢 | 𞡣 | 𞡤 | 𞡥 | 𞡦 | 𞡧 | 𞡨 | 𞡩 | 𞡪 | 𞡫 | 𞡬 | 𞡭 | 𞡮 | 𞡯 |

| U+1E87x | 𞡰 | 𞡱 | 𞡲 | 𞡳 | 𞡴 | 𞡵 | 𞡶 | 𞡷 | 𞡸 | 𞡹 | 𞡺 | 𞡻 | 𞡼 | 𞡽 | 𞡾 | 𞡿 |

| U+1E88x | 𞢀 | 𞢁 | 𞢂 | 𞢃 | 𞢄 | 𞢅 | 𞢆 | 𞢇 | 𞢈 | 𞢉 | 𞢊 | 𞢋 | 𞢌 | 𞢍 | 𞢎 | 𞢏 |

| U+1E89x | 𞢐 | 𞢑 | 𞢒 | 𞢓 | 𞢔 | 𞢕 | 𞢖 | 𞢗 | 𞢘 | 𞢙 | 𞢚 | 𞢛 | 𞢜 | 𞢝 | 𞢞 | 𞢟 |

| U+1E8Ax | 𞢠 | 𞢡 | 𞢢 | 𞢣 | 𞢤 | 𞢥 | 𞢦 | 𞢧 | 𞢨 | 𞢩 | 𞢪 | 𞢫 | 𞢬 | 𞢭 | 𞢮 | 𞢯 |

| U+1E8Bx | 𞢰 | 𞢱 | 𞢲 | 𞢳 | 𞢴 | 𞢵 | 𞢶 | 𞢷 | 𞢸 | 𞢹 | 𞢺 | 𞢻 | 𞢼 | 𞢽 | 𞢾 | 𞢿 |

| U+1E8Cx | 𞣀 | 𞣁 | 𞣂 | 𞣃 | 𞣄 | 𞣇 | 𞣈 | 𞣉 | 𞣊 | 𞣋 | 𞣌 | 𞣍 | 𞣎 | 𞣏 | ||

| U+1E8Dx | 𞣐 | 𞣑 | 𞣒 | 𞣓 | 𞣔 | 𞣕 | 𞣖 | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ a b c Everson & Tuchscherer 2012.

- ^ Tuchscherer 1995, p. 170.

- ^ Tuchscherer 1995, p. 175.

- ^ Unseth, Peter. 2011. Invention of Scripts in West Africa for Ethnic Revitalization. In The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts, ed. by Joshua A. Fishman and Ofelia García, pp. 23-32. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Tuchscherer 1995, p. 183.

- ^ Tuchscherer 1995, p. 185.

Sources

- Everson, Michael; Tuchscherer, Konrad (2012-01-24). "N4167: Revised proposal for encoding the Mende script in the SMP of the UCS" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2.

- Tuchscherer, Konrad (1995). "African Script and Scripture: The History of the Kikakui (Mende) Writing System for Bible Translations". African Languages and Cultures. 8 (2): 169–188. JSTOR 1771691.