Kenwood House

| Kenwood House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | English country house |

| Location | Hampstead Heath, NW3 |

| Coordinates | 51°34′17″N 0°10′3″W / 51.57139°N 0.16750°W |

| Area | London Borough of Camden |

| Built | 17th century |

| Rebuilt | 1764–1779 |

| Architect | Robert Adam (18th century remodelling) |

| Architectural style(s) | Georgian and Neoclassical |

| Owner | Historic England |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Kenwood House (Iveagh Bequest) |

| Designated | 10 June 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1379242 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Service wing and outbuildings to Kenwood House |

| Reference no. | 1379244 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Sham bridge to south of Kenwood House |

| Reference no. | 1379245 |

| Designated | 1 October 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1000142 |

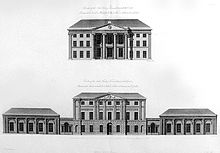

Kenwood House (also known as the Iveagh Bequest) is a stately home in Hampstead, London, on the northern boundary of Hampstead Heath. The present house, built in the late 17th century, was remodelled in the 18th century for William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield by Scottish architect Robert Adam, serving as a residence for the Earls of Mansfield until the 20th century.

The house and part of the grounds were bought from the 6th Earl of Mansfield in 1925 by Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, and donated to the nation in 1927. The entire estate came under ownership of the London County Council and was open to the public by the end of the 1920s. It remains a popular local tourist attraction.

Location

The house is at the north edge of Hampstead Heath, to the south of Hampstead Lane (the B519).[1] It is in the London Borough of Camden, just south of its boundary with the London Borough of Haringey.

History

Early history

The original house on the property was presumed to have been built around 1616 by the King's Printer, John Bill, and was known as Caen Wood House.[1][2] It was acquired in 1694 by the Surveyor-General of the Ordnance, William Bridges, who demolished the house and rebuilt it; the original brick structure remains intact under the facade added in the 18th century.[1] The orangery was added in about 1700.[3] Bridges sold the house in 1704, and it went under several owners until 1754, when it was bought by the future Earl of Mansfield, William Murray, who was the Lord Chief Justice.[1]

Mansfield family

In 1764, Lord Mansfield commissioned Robert Adam to remodel the house. Adam was given complete freedom to design it as he chose. He added the library, one of his most famous interiors, to balance the orangery, and accommodate Lord Mansfield's extensive book collection. He also designed the Ionic portico at the entrance.[1][4]

In June 1780, Lord Mansfield's Bloomsbury townhouse was ransacked and destroyed during the Gordon Riots. The Earl and Countess fled, then the rioters targeted Kenwood next due to its proximity. His nephew Lord Stormont wrote to George III that he had ordered light cavalry to be dispatched to Kenwood. To stall the rioters, free ale was given from the Spaniards Inn, assisted by Lord Mansfield's steward using wine from the house. They successfully stalled the mobs until the armed cavalry arrived to protect the house.[5]

Following the 1st Earl's death in 1793, ownership passed to his nephew, David Murray. With his late uncle's approval, he commissioned an extension of the property, initially by Robert Nasmith, then by George Saunders. Saunders added two wings on the north side, one wing for the first permanent dining room at Kenwood, along with the offices, kitchen buildings and brewery (now the restaurant) to the side.[1] A dairy was added at this time to supply Kenwood House with milk and cheese.[6] The main Hampstead–Highgate road was moved to the north between 1793 and 1796 so that it would not run directly alongside the property.[4]

In 1794, George III visited the 2nd Earl of Mansfield at Kenwood House, Queen Charlotte said that the king was curious about the architectural improvements.[7]

The 2nd Earl died in 1796, and ownership passed to his son, David William Murray, 3rd Earl of Mansfield. William Atkinson undertook essential structural reinforcement to the house between 1803 and 1839, ensuring that Kenwood would stand the test of time.[5] The property remained with the Mansfields throughout the rest of the century, [1] but the Mansfields preferred to live at their Scottish seat, Scone Palace.

In July 1835, William IV and Queen Adelaide paid a royal visit to Kenwood, this was attended by 800 of the nobility and gentry, scattered around the Kenwood garden. The Marchioness of Salisbury wrote "The King and Queen and Royalties extremely well pleased: the King trotted about with Lord M. in the most active manner".[8]

The 6th Earl of Mansfield, Alan David Murray, inherited Kenwood from his brother in 1906, but soon decided to sell it. First he leased it, and after two years of negotiations, the house was leased in 1910 to the exiled Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich of Russia and his morganatic wife, Countess Sophie of Merenberg. [9] In 1914 the couple hosted a dinner and ball attended by European royalty including George V and Queen Mary.[10] The Grand Duke stayed at Kenwood until 1917, followed by American millionairess Nancy Leeds who moved out in 1920. In 1922 Lord Mansfield sold off the contents of the house and its future was uncertain.[11]

Modern history

Part of the grounds were bought by the Kenwood Preservation Council in 1922, after there had been threats that it would be sold to a building syndicate. This land came under control of the London County Council in 1924 and was opened to the public the following year by King George V.[1] Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, a rich Anglo-Irish businessman and philanthropist of the Guinness family, bought the house and the remaining 74 acres (30 ha) not under public ownership from the Mansfield family in 1925 and left it to the nation upon his death in 1927; it was opened to the public the following year. Some of the furniture sold in 1922 has since been bought back. The paintings are from Iveagh's collection.[1]

Kenwood House was closed at the start of World War II. Following the war, the house came under ownership of the London County Council, and it re-opened in 1950.[1] The late 18th-century extensions by Saunders were restored from 1955 to 1959.[4] Ownership transferred to the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1965; following the GLC's demise in 1986, English Heritage took over responsibility for the estate.[1]

The house was closed for major renovations from 2012 until late 2013, partly funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. This included repairing the Westmorland slate roof, redisplaying the Iveagh Bequest paintings in the south of the house, and redecorating the structure to closer resemble Adam's original design.[12]

In 2019, 134,238 people visited the house.[13]

Estate

There are two drives leading to the house from Hampstead Lane. Each has a gated white-brick lodge. The north, or main entrance front of the house was designed by Robert Adam and is set in Stucco with a central portico. The south front is constructed out of a single Stucco block. It was restored to its original design in 1975. To the east of the house is the service wing, constructed from London stock brick. Opposite this is the brick house, designed as a cold-plunge bath.[1]

The estate has a designed landscape with gardens near the house, probably originally designed by Humphry Repton, contrasting with some surrounding woodland, and the naturalistic Hampstead Heath to the south.[1] There is also a garden designed by Arabella Lennox-Boyd.[14]

The estate is Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[15] One third of the estate is a Site of Special Scientific Interest, particularly the ancient woodlands. These are home to many birds and insects and the largest Pipistrelle bat roost in London.

There are sculptures by Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Eugène Dodeigne in the gardens near the house.

|

Music concerts, originally classical but later predominantly pop concerts, were held by the lake on Saturday evenings every summer from 1951 until 2006, attracting many people to picnic and enjoy the music, scenery and fireworks. In February 2007, English Heritage decided to abandon these concerts owing to restrictions placed on them after protests from some local residents. On 19 March 2008, it was announced that the concerts would return to a new location on the Pasture Ground within the Kenwood Estate, with the number of concerts limited to eight per season.[16]

Art

Kenwood House contains a significant number of historic paintings and other works of art, including 63 Old Master paintings.[18] Paintings of note include

- The Guitar Player by Johannes Vermeer

- Self Portrait with Two Circles, a late Rembrandt self-portrait

- Portrait of Pieter van den Broecke, by Frans Hals

- Thomas Gainsborough, 'Portrait of Countess Howe' (wife of Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe)

- Edwin Henry Landseer, 'Hunting in the Olden Times'

Other painters include

- Joshua Reynolds, 'The Hon'ble Mrs Tollemache as Miranda'

- Angelica Kauffman

- John Crome

- Claude de Jongh

- George Morland

- Anthony van Dyck

- William Larkin

- J. M. W. Turner

- Arthur Boyd Houghton

- François Boucher

- Thomas Lawrence, 'Miss Murray'

- Henry Raeburn

- George Romney

- Jan Baptist Weenix

- Joseph Wright of Derby

Most of the works were acquired by Iveagh in the 1880s–1890s and are mainly Old Master portraits, landscapes and 17th century Dutch and Flemish works and British artists. Others were not part of the Iveagh Bequest but were added to the collection after his death because of a connection with Kenwood House.[19]

There is also a collection of shoe buckles, jewellery and portrait miniatures.

In 2002, a selection of the Suffolk Collection of Stuart portraits was moved to Kenwood from Ranger's House, Greenwich.[20]

In 2012, an exhibition of works from the art collection, Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Gainsborough: The Treasures of Kenwood House, London began a tour of museums in the United States while Kenwood House was undergoing renovations; many of the works had never been outside Britain. The exhibit opened 6 June 2013 in Little Rock, Arkansas at the Arkansas Arts Center.[21][19]

Cultural references

The house was the subject of a Margaret Calkin James poster in the 1930s, seen by many commuters on the London Underground.

The 1999 British feature film Notting Hill had a scene filmed here.

The 1995 British feature film Sense and Sensibility had scenes filmed here.

Many scenes in the 2013 film Belle, in which William Murray figures as a character, are set in the house or its grounds, although filmed elsewhere.[22]

A scene from the 2016 novel Swing Time by Zadie Smith is set on the grounds of the estate.

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 455.

- ^ FK staff (9 April 2014). "History of Kenwood House and the Friends of Kenwood". Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ "Kenwood House". Art Fund. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Kenwood House (Iveagh Bequest) (1379242)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b Bryant 1990, p. 64.

- ^ "More than £40,000 needed to restore 18th century Kenwood Dairy". Ham&High. 8 October 2012. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "George III's Visit to Kenwood House in 1794". Georgian Papers Programme. 8 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Bryant 1990, p. 66.

- ^ Bryant 1990, p. 68.

- ^ "Social Record". Daily Mail. 12 June 1914. p. 4.

- ^ "History of Kenwood". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "History of Kenwood". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "Famous film and TV locations you can visit in the UK". House and Garden. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Historic England, "Kenwood (1000142)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 June 2017

- ^ "IMG and English Heritage announce stunning line up for Kenwood House Picnic Concerts". Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ^ Bryant, Julius (2003). Kenwood, Paintings in the Iveagh Bequest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 70–77. ISBN 978-0-300-10206-2.

- ^ "The 100 best paintings in London - Kenwood House". Time Out. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Masterpieces from London's Kenwood House tours the US, brings works by Rembrandt, Gainsborough". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 1 June 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 256.

- ^ Glentzer, Molly (8 June 2012). "British treasures leave home for the MFAH". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Internet Movie Database. "Belle Filming Locations". IMDb. Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

Sources

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

- Bryant, Julius (1990). The Iveagh Bequest: Kenwood. Oxford, UK: London Historic House Museums Trust. ISBN 9781850742784.

- The Buildings of England London 4: North. Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner. ISBN 0-300-09653-4.

- Kenwood: The Iveagh Bequest. Julius Bryant. (English Heritage publication).

- George III. Andrew Roberts. (2021) Allen Lane. ISBN 9780241413340.

External links

- English Heritage website for the house

- 'The Iconic Art of Kenwood House' on Google Arts & Culture

- "The Friends of Kenwood (or The Friends of the Iveagh Bequest)". 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2014.